User login

Rate of Clinical Trial Enrollment in Patients Treated for DLBCL Within the Veterans Health Administration

BACKGROUND: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is curable in most patients, however this high cure rate is mostly reserved for those who achieve a complete remission with first line treatment. In patients who have relapsed/refractory disease the cure rate is significantly lower. There are limited studies that have previously investigated the rate of clinical trial discussion and enrollment among DLBCL patients. Our aim, as part of a larger study, was to determine the rate of clinical trial enrollment for patients diagnosed with DLBCL at the Veterans Health Administration system (VHA), a population that traditionally experiences poorer outcomes when compared to the community and academic centers.

METHODS: We performed a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with DLBCL in the VHA nationwide from 01/01/2011 to 12/31/2017. Patients treated outside of the VHA and patients with primary DLBCL of the CNS were excluded. During our inclusion period, we randomly selected patients and evaluated the number of patients that engaged in discussions with their providers about clinical trials and the number of patients that eventually enrolled in trials.

RESULTS: In total, 721 patients met our inclusion criteria. Median age was 67 and the majority of patients were white (74.5%), male (96.8%), had an ECOG of 2 (83.7%) and presented with advanced stage disease (stage IV: 40.3% and stage III: 26.5%). Of all the patients included in our study 3.7% engaged in discussion about clinical trials and amongst relapsed/ refractory patients (N=182), 12.6% engaged in discussion. The rate of clinical trial enrollment was 1.8% in all patients and 6% in relapsed/refractory patients.

CONCLUSION: Our results show a low rate of 1.8% of DLBCL patients enrolling in clinical trials. These rates are improved but remain low at 6% in relapsed/ refractory patients with only 12.6 % of all relapsed/refractory patients engaging in discussions with their provider about clinical trials, despite NCCN’s recommendation for clinical trial consideration in this subset of DLBCL patients. These results are concerning and show a need to identify and understand the barriers to enrollment in this population in addition to the implementation of mitigation practices.

BACKGROUND: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is curable in most patients, however this high cure rate is mostly reserved for those who achieve a complete remission with first line treatment. In patients who have relapsed/refractory disease the cure rate is significantly lower. There are limited studies that have previously investigated the rate of clinical trial discussion and enrollment among DLBCL patients. Our aim, as part of a larger study, was to determine the rate of clinical trial enrollment for patients diagnosed with DLBCL at the Veterans Health Administration system (VHA), a population that traditionally experiences poorer outcomes when compared to the community and academic centers.

METHODS: We performed a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with DLBCL in the VHA nationwide from 01/01/2011 to 12/31/2017. Patients treated outside of the VHA and patients with primary DLBCL of the CNS were excluded. During our inclusion period, we randomly selected patients and evaluated the number of patients that engaged in discussions with their providers about clinical trials and the number of patients that eventually enrolled in trials.

RESULTS: In total, 721 patients met our inclusion criteria. Median age was 67 and the majority of patients were white (74.5%), male (96.8%), had an ECOG of 2 (83.7%) and presented with advanced stage disease (stage IV: 40.3% and stage III: 26.5%). Of all the patients included in our study 3.7% engaged in discussion about clinical trials and amongst relapsed/ refractory patients (N=182), 12.6% engaged in discussion. The rate of clinical trial enrollment was 1.8% in all patients and 6% in relapsed/refractory patients.

CONCLUSION: Our results show a low rate of 1.8% of DLBCL patients enrolling in clinical trials. These rates are improved but remain low at 6% in relapsed/ refractory patients with only 12.6 % of all relapsed/refractory patients engaging in discussions with their provider about clinical trials, despite NCCN’s recommendation for clinical trial consideration in this subset of DLBCL patients. These results are concerning and show a need to identify and understand the barriers to enrollment in this population in addition to the implementation of mitigation practices.

BACKGROUND: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is curable in most patients, however this high cure rate is mostly reserved for those who achieve a complete remission with first line treatment. In patients who have relapsed/refractory disease the cure rate is significantly lower. There are limited studies that have previously investigated the rate of clinical trial discussion and enrollment among DLBCL patients. Our aim, as part of a larger study, was to determine the rate of clinical trial enrollment for patients diagnosed with DLBCL at the Veterans Health Administration system (VHA), a population that traditionally experiences poorer outcomes when compared to the community and academic centers.

METHODS: We performed a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with DLBCL in the VHA nationwide from 01/01/2011 to 12/31/2017. Patients treated outside of the VHA and patients with primary DLBCL of the CNS were excluded. During our inclusion period, we randomly selected patients and evaluated the number of patients that engaged in discussions with their providers about clinical trials and the number of patients that eventually enrolled in trials.

RESULTS: In total, 721 patients met our inclusion criteria. Median age was 67 and the majority of patients were white (74.5%), male (96.8%), had an ECOG of 2 (83.7%) and presented with advanced stage disease (stage IV: 40.3% and stage III: 26.5%). Of all the patients included in our study 3.7% engaged in discussion about clinical trials and amongst relapsed/ refractory patients (N=182), 12.6% engaged in discussion. The rate of clinical trial enrollment was 1.8% in all patients and 6% in relapsed/refractory patients.

CONCLUSION: Our results show a low rate of 1.8% of DLBCL patients enrolling in clinical trials. These rates are improved but remain low at 6% in relapsed/ refractory patients with only 12.6 % of all relapsed/refractory patients engaging in discussions with their provider about clinical trials, despite NCCN’s recommendation for clinical trial consideration in this subset of DLBCL patients. These results are concerning and show a need to identify and understand the barriers to enrollment in this population in addition to the implementation of mitigation practices.

Assessing Risk for and Management of Secondary CNS Involvement in Patients With DLBCL Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA)

INTRODUCTION: In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), approximately 5-10% of patients develop secondary central nervous system (CNS) involvement. CNS disease is associated with very poor outcomes. Therefore, it is important to identify patients at risk, via the CNS International Prognostic Index (IPI), in order to initiate appropriate interventions. Additional independent risk factors for CNS involvement include HIV-related lymphoma and high-grade B-cell lymphomas. The purpose of this study was to assess for appropriate CNS evaluation and prophylaxis in DLBCL patients within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

METHODS: We performed a retrospective chart review of 1,605 randomly selected patients seen in the VHA nationwide who were diagnosed with lymphoma between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2017. We included patients diagnosed with DLBCL and excluded patients diagnosed or treated outside the VHA. We evaluated CNS IPI score, HIV status, pathology reports to identify high-grade lymphomas, performance of lumbar puncture (LP), and administration of CNS prophylaxis.

RESULTS: A total of 725 patients met our inclusion criteria. Patients were predominantly male (96.8%), white (74.5%), had a median age of 67, and presented with advanced disease (stage III 26.5%, stage IV 40.3%). From the included population, 190 (26.2%) had a highrisk CNS IPI score. Of those with high-risk CNS IPI scores, 64 (33.7%) underwent LP and 46 (24.2%) were treated with CNS prophylaxis. 23 (3.2%) were HIV positive; of those, 14 (60.8%) underwent LP and 4 (17.4%) were treated with CNS prophylaxis. FISH results were available in only 242 (33.4%) of patients and of these, 25 (10.3%) met criteria for high-grade lymphoma. Of those with high-grade lymphoma, 9 (36%) underwent LP and 7 (28%) were treated with CNS prophylaxis.

CONCLUSIONS: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that patients at high risk for CNS involvement undergo LP and treatment with CNS prophylaxis. This study found that within the VHA, patients with DLBCL at high risk for CNS involvement are not being evaluated with LPs or treated with CNS prophylaxis as often as indicated, based on CNS IPI, HIV status, and high-grade pathology. We demonstrate a need for improvement in the evaluation and treatment of these patients in order to improve outcomes.

INTRODUCTION: In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), approximately 5-10% of patients develop secondary central nervous system (CNS) involvement. CNS disease is associated with very poor outcomes. Therefore, it is important to identify patients at risk, via the CNS International Prognostic Index (IPI), in order to initiate appropriate interventions. Additional independent risk factors for CNS involvement include HIV-related lymphoma and high-grade B-cell lymphomas. The purpose of this study was to assess for appropriate CNS evaluation and prophylaxis in DLBCL patients within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

METHODS: We performed a retrospective chart review of 1,605 randomly selected patients seen in the VHA nationwide who were diagnosed with lymphoma between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2017. We included patients diagnosed with DLBCL and excluded patients diagnosed or treated outside the VHA. We evaluated CNS IPI score, HIV status, pathology reports to identify high-grade lymphomas, performance of lumbar puncture (LP), and administration of CNS prophylaxis.

RESULTS: A total of 725 patients met our inclusion criteria. Patients were predominantly male (96.8%), white (74.5%), had a median age of 67, and presented with advanced disease (stage III 26.5%, stage IV 40.3%). From the included population, 190 (26.2%) had a highrisk CNS IPI score. Of those with high-risk CNS IPI scores, 64 (33.7%) underwent LP and 46 (24.2%) were treated with CNS prophylaxis. 23 (3.2%) were HIV positive; of those, 14 (60.8%) underwent LP and 4 (17.4%) were treated with CNS prophylaxis. FISH results were available in only 242 (33.4%) of patients and of these, 25 (10.3%) met criteria for high-grade lymphoma. Of those with high-grade lymphoma, 9 (36%) underwent LP and 7 (28%) were treated with CNS prophylaxis.

CONCLUSIONS: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that patients at high risk for CNS involvement undergo LP and treatment with CNS prophylaxis. This study found that within the VHA, patients with DLBCL at high risk for CNS involvement are not being evaluated with LPs or treated with CNS prophylaxis as often as indicated, based on CNS IPI, HIV status, and high-grade pathology. We demonstrate a need for improvement in the evaluation and treatment of these patients in order to improve outcomes.

INTRODUCTION: In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), approximately 5-10% of patients develop secondary central nervous system (CNS) involvement. CNS disease is associated with very poor outcomes. Therefore, it is important to identify patients at risk, via the CNS International Prognostic Index (IPI), in order to initiate appropriate interventions. Additional independent risk factors for CNS involvement include HIV-related lymphoma and high-grade B-cell lymphomas. The purpose of this study was to assess for appropriate CNS evaluation and prophylaxis in DLBCL patients within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

METHODS: We performed a retrospective chart review of 1,605 randomly selected patients seen in the VHA nationwide who were diagnosed with lymphoma between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2017. We included patients diagnosed with DLBCL and excluded patients diagnosed or treated outside the VHA. We evaluated CNS IPI score, HIV status, pathology reports to identify high-grade lymphomas, performance of lumbar puncture (LP), and administration of CNS prophylaxis.

RESULTS: A total of 725 patients met our inclusion criteria. Patients were predominantly male (96.8%), white (74.5%), had a median age of 67, and presented with advanced disease (stage III 26.5%, stage IV 40.3%). From the included population, 190 (26.2%) had a highrisk CNS IPI score. Of those with high-risk CNS IPI scores, 64 (33.7%) underwent LP and 46 (24.2%) were treated with CNS prophylaxis. 23 (3.2%) were HIV positive; of those, 14 (60.8%) underwent LP and 4 (17.4%) were treated with CNS prophylaxis. FISH results were available in only 242 (33.4%) of patients and of these, 25 (10.3%) met criteria for high-grade lymphoma. Of those with high-grade lymphoma, 9 (36%) underwent LP and 7 (28%) were treated with CNS prophylaxis.

CONCLUSIONS: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that patients at high risk for CNS involvement undergo LP and treatment with CNS prophylaxis. This study found that within the VHA, patients with DLBCL at high risk for CNS involvement are not being evaluated with LPs or treated with CNS prophylaxis as often as indicated, based on CNS IPI, HIV status, and high-grade pathology. We demonstrate a need for improvement in the evaluation and treatment of these patients in order to improve outcomes.

Assessing Pathologic Evaluation in Patients with DLBCL Within the Veterans Health Administration

INTRODUCTION: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Patients with DLBCL refractory to initial treatment or who experience relapse have low rates of prolonged disease-free survival. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) revealing rearrangements in the MYC gene along with either the BCL2 or BCL6 genes (double- and triple-hit lymphomas) demonstrate inferior outcomes when treated with standard front-line chemoimmunotherapy. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) testing for MUM1, CD10, BCL6, and MYC also provides important prognostic information and is used in the Hans algorithm to determine the cell of origin. We assessed how frequently these crucial tests were performed on DLBCL patients within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

METHODS: We performed a retrospective chart review of 1,605 randomly selected records of patients diagnosed with lymphoma seen within the VHA nationwide between 1/1/2011 and 12/31/2017. We included patients diagnosed with DLBCL. We excluded patients whose workup and treatment were outside of the VHA system, and patients with primary CNS lymphoma. We analyzed pathology reports. The proportion of patients who had IHC and FISH testing for each marker was assessed.

RESULTS: 725 patients were included in the study. Our patients were predominantly male (96.8%), with a median age of 67 years. Out of the patients analyzed, IHC to determine cell of origin was performed in 481 (66.3%). Out of those tested, 316 (65.7%) were of germinal center B-cell (GCB) origin, and 165 (34.3%) were non-GCB origin. FISH testing was performed in only 242 patients (33.4%). Out of the population tested, 25 (10.3%) were double- or triple-hit.

CONCLUSION: Pathological characterization is key to the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of DLBCL. It is recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) to obtain IHC testing for MUM1, BCL6, CD10, and MYC, and FISH testing for MYC (with BCL2 and BCL6 if MYC is positive) in all patients with DLBCL. Our study shows that more than one half of patients did not have FISH testing, and that cell of origin was not determined in about one third of patients, indicating a need for improved testing of these protein expressions and gene rearrangements within the VHA.

INTRODUCTION: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Patients with DLBCL refractory to initial treatment or who experience relapse have low rates of prolonged disease-free survival. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) revealing rearrangements in the MYC gene along with either the BCL2 or BCL6 genes (double- and triple-hit lymphomas) demonstrate inferior outcomes when treated with standard front-line chemoimmunotherapy. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) testing for MUM1, CD10, BCL6, and MYC also provides important prognostic information and is used in the Hans algorithm to determine the cell of origin. We assessed how frequently these crucial tests were performed on DLBCL patients within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

METHODS: We performed a retrospective chart review of 1,605 randomly selected records of patients diagnosed with lymphoma seen within the VHA nationwide between 1/1/2011 and 12/31/2017. We included patients diagnosed with DLBCL. We excluded patients whose workup and treatment were outside of the VHA system, and patients with primary CNS lymphoma. We analyzed pathology reports. The proportion of patients who had IHC and FISH testing for each marker was assessed.

RESULTS: 725 patients were included in the study. Our patients were predominantly male (96.8%), with a median age of 67 years. Out of the patients analyzed, IHC to determine cell of origin was performed in 481 (66.3%). Out of those tested, 316 (65.7%) were of germinal center B-cell (GCB) origin, and 165 (34.3%) were non-GCB origin. FISH testing was performed in only 242 patients (33.4%). Out of the population tested, 25 (10.3%) were double- or triple-hit.

CONCLUSION: Pathological characterization is key to the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of DLBCL. It is recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) to obtain IHC testing for MUM1, BCL6, CD10, and MYC, and FISH testing for MYC (with BCL2 and BCL6 if MYC is positive) in all patients with DLBCL. Our study shows that more than one half of patients did not have FISH testing, and that cell of origin was not determined in about one third of patients, indicating a need for improved testing of these protein expressions and gene rearrangements within the VHA.

INTRODUCTION: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Patients with DLBCL refractory to initial treatment or who experience relapse have low rates of prolonged disease-free survival. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) revealing rearrangements in the MYC gene along with either the BCL2 or BCL6 genes (double- and triple-hit lymphomas) demonstrate inferior outcomes when treated with standard front-line chemoimmunotherapy. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) testing for MUM1, CD10, BCL6, and MYC also provides important prognostic information and is used in the Hans algorithm to determine the cell of origin. We assessed how frequently these crucial tests were performed on DLBCL patients within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

METHODS: We performed a retrospective chart review of 1,605 randomly selected records of patients diagnosed with lymphoma seen within the VHA nationwide between 1/1/2011 and 12/31/2017. We included patients diagnosed with DLBCL. We excluded patients whose workup and treatment were outside of the VHA system, and patients with primary CNS lymphoma. We analyzed pathology reports. The proportion of patients who had IHC and FISH testing for each marker was assessed.

RESULTS: 725 patients were included in the study. Our patients were predominantly male (96.8%), with a median age of 67 years. Out of the patients analyzed, IHC to determine cell of origin was performed in 481 (66.3%). Out of those tested, 316 (65.7%) were of germinal center B-cell (GCB) origin, and 165 (34.3%) were non-GCB origin. FISH testing was performed in only 242 patients (33.4%). Out of the population tested, 25 (10.3%) were double- or triple-hit.

CONCLUSION: Pathological characterization is key to the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of DLBCL. It is recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) to obtain IHC testing for MUM1, BCL6, CD10, and MYC, and FISH testing for MYC (with BCL2 and BCL6 if MYC is positive) in all patients with DLBCL. Our study shows that more than one half of patients did not have FISH testing, and that cell of origin was not determined in about one third of patients, indicating a need for improved testing of these protein expressions and gene rearrangements within the VHA.

Hospitalists as Triagists: Description of the Triagist Role across Academic Medical Centers

Hospital medicine has grown dramatically over the past 20 years.1,2 A recent survey regarding hospitalists’ clinical roles showed an expansion to triaging emergency department (ED) medical admissions and transfers from outside hospitals.3 From the hospitalist perspective, triaging involves the evaluation of patients for potential admission.4 With scrutiny on ED metrics, such as wait times (https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html), health system administrators have heightened expectations for efficient patient flow, which increasingly falls to hospitalists.5-7

Despite the growth in hospitalists’ triagist activities, there has been little formal assessment of their role. We hypothesized that this role differs from inpatient care in significant ways.6-8 We sought to describe the triagist role in adult academic inpatient medicine settings to understand the responsibilities and skill set required.

METHODS

Ten academic medical center (AMC) sites were recruited from Research Committee session attendees at the 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine national meeting and the 2014 Society of General Internal Medicine southern regional meeting. The AMCs were geographically diverse: three Western, two Midwestern, two Southern, one Northeastern, and two Southeastern. Site representatives were identified and completed a web-based questionnaire about their AMC (see Appendix 1 for the information collected). Clarifications regarding survey responses were performed via conference calls between the authors (STV, ESW) and site representatives.

Hospitalist Survey

In January 2018, surveys were sent to 583 physicians who worked as triagists. Participants received an anonymous 28-item RedCap survey by e-mail and were sent up to five reminder e-mails over six weeks (see Appendix 2 for the questions analyzed in this paper). Respondents were given the option to be entered in a gift card drawing.

Demographic information and individual workflow/practices were obtained. A 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) was used to assess hospitalists’ concurrence with current providers (eg, ED, clinic providers) regarding the management and whether patients must meet the utilization management (UM) criteria for admission. Time estimates used 5% increments and were categorized into four frequency categories based on the local modes provided in responses: Seldom (0%-10%), Occasional (15%-35%), Half-the-Time (40%-60%), and Frequently (65%-100%). Free text responses on effective/ineffective triagist qualities were elicited. Responses were included for analysis if at least 70% of questions were completed.

Data Analysis

Quantitative

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences across AMCs in the time spent on in-person evaluation and communication. Weighting, based on the ratio of hospitalists to survey respondents at each AMC, was used to calculate the average institutional percentages across the study sample.

Qualitative

Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis.9 Three independent reviewers (STV, JC, ESW) read, analyzed, and grouped the responses by codes. Codes were then assessed for overlap and grouped into themes by one reviewer (STV). A table of themes with supporting quotes and the number of mentions was subsequently developed by all three reviewers. Similar themes were combined to create domains. The domains were reviewed by the steering committee members to create a consensus description (Appendix 3).

The University of Texas Health San Antonio’s Institutional Review Board and participating institutions approved the study as exempt.

RESULTS

Site Characteristics

Representatives from 10 AMCs reported data on a range of one to four hospitals for a total of 22 hospitals. The median reported that the number of medical patients admitted in a 24-hour period was 31-40 (range, 11-20 to >50). The median group size of hospitalists was 41-50 (range, 0-10 to >70).

The survey response rate was 40% (n = 235), ranging from 9%-70% between institutions. Self-identified female hospitalists accounted for 52% of respondents. Four percent were 25-29 years old, 66% were 30-39 years old, 24% were 40-49 years old, and 6% were ≥50 years old. The average clinical time spent as a triagist was 16%.

Description of Triagist Activities

The activities identified by the majority of respondents across all sites included transferring patients within the hospital (73%), and assessing/approving patient transfers from outside hospitals and clinics (82%). Internal transfer activities reported by >50% of respondents included allocating patients within the hospital or bed capacity coordination, assessing intensive care unit transfers, assigning ED admissions, and consulting other services. The ED accounted for an average of 55% of calls received. Respondents also reported being involved with the documentation related to these activities.

Similarities and Differences across AMCs

Two AMCs did not have a dedicated triagist; instead, physicians supervised residents and advanced practice providers. Among the eight sites with triagists, triaging was predominantly done by faculty physicians contacted via pagers. At seven of these sites, 100% of hospitalists worked as triagists. The triage service was covered by faculty physicians from 8-24 hours per day.

Bed boards and transfer centers staffed by registered nurses, nurse coordinators, house supervisors, or physicians were common support systems, though this infrastructure was organized differently across institutions. A UM review before admission was performed at three institutions 24 hours/day. The remaining institutions reviewed patients retrospectively.

Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists across all sites “Disagreed” or “Strongly disagreed” that a patient must meet UM criteria for admission. Forty-two percent had “Frequent” different opinions regarding patient management than the consulting provider.

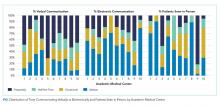

Triagist and current provider communication practices varied widely across AMCs (Figure). There was significant variability in verbal communication (P = .02), with >70% of respondents at two AMCs reporting verbal communication at least half the time, but <30% reporting this frequency at two other AMCs. Respondents reported variable use of electronic communication (ie, notes/orders in the electronic health record) across AMCs (

The practice of evaluating patients in person also varied significantly across AMCs (P < .0001, Figure). Across hospitalists, only 28% see patients in person about “Half-the-Time” or more.

Differences within AMCs

Variability within AMCs was greatest for the rate of verbal communication practices, with a typical interquartile range (IQR) of 20% to 90% among the hospitalists within a given AMC and for the rate of electronic communication with a typical IQR of 0% to 50%. For other survey questions, the IQR was typically 15 to 20 percentage points.

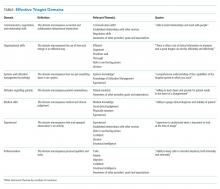

Thematic Analysis

We received 207 and 203 responses (88% and 86%, respectively) to the open-ended questions “What qualities does an effective triagist have?’ and ‘What qualities make a triagist ineffective?” We identified 22 themes for effective and ineffective qualities, which were grouped into seven domains (Table). All themes had at least three mentions by respondents. The three most frequently mentioned themes, communication skills, efficiency, and systems knowledge, had greater than 60 mentions.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the triagist role at 10 AMCs describes critical triagist functions and identifies key findings across and within AMCs. Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists reported admitting patients even when the patient did not meet the admission criteria, consistent with previous research demonstrating the influence of factors other than clinical disease severity on triage decisions.10 However, preventable admissions remain a hospital-level quality metric.11,12 Triagists must often balance each patient’s circumstances with the complexities of the system. Juggling the competing demands of the system while providing patient-centered care can be challenging and may explain why attending physicians are more frequently filling this role.13

Local context/culture is likely to play a role in the variation across sites; however, compensation for the time spent may also be a factor. If triage activities are not reimbursable, this could lead to less documentation and a lower likelihood that patients are evaluated in person.14 This reason may also explain why all hospitalists were required to serve as a triagist at most sites.

Currently, no consensus definition of the triagist role has been developed. Our results demonstrate that this role is heterogeneous and grounded in the local healthcare system practices. We propose the following working definition of the triagist: a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting. A triagist should be equipped with a skill set that includes not only clinical knowledge but also emphasizes systems knowledge, awareness of others’ goals, efficiency, an ability to communicate effectively, and the knowledge of UM. We recommend that medical directors of hospitalist programs focus their attention on locally specific, systems-based skills development when orienting new hospitalists. The financial aspects of cost should be considered and delineated as well.

Our analysis is limited in several respects. Participant AMCs were not randomly chosen, but do represent a broad array of facility types, group size, and geographic regions. The low response rates at some AMCs may result in an inaccurate representation of those sites. Data was not obtained on hospitalists that did not respond to the survey; therefore, nonresponse bias may affect outcomes. This research used self-report rather than direct observation, which could be subject to recall and social desirability bias. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to nonacademic institutions.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalist role as triagist at AMCs emphasizes communication, organizational skills, efficiency, systems-based practice, and UM knowledge. Although we found significant variation across and within AMCs, internal transfer activities were common across programs. Hospitalist programs should focus on systems-based skills development to prepare hospitalists for the role. The skill set necessary for triagist responsibilities also has implications for internal medicine resident education.4 With increasing emphasis on value and system effectiveness in care delivery, further studies of the triagist role should be undertaken.

Acknowledgments

The TRIAGIST Collaborative Group consists of: Maralyssa Bann, MD, Andrew White, MD (University of Washington); Jagriti Chadha, MD (University of Kentucky); Joel Boggan, MD (Duke University); Sherwin Hsu, MD (UCLA); Jeff Liao, MD (Harvard Medical School); Tabatha Matthias, DO (University of Nebraska Medical Center); Tresa McNeal, MD (Scott and White Texas A&M); Roxana Naderi, MD, Khooshbu Shah, MD (University of Colorado); David Schmit, MD (University of Texas Health San Antonio); Manivannan Veerasamy, MD (Michigan State University).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the po

1. Kisuule F, Howell EE. Hospitalists and their impact on quality, patient safety, and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015; 42(3):433-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2015.05.003.

2. Wachter, RM, Goldman, L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11): 1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

3. Vasilevskis EE, Knebel RJ, Wachter RM, Auerbach AD. California hospital leaders’ views of hospitalists: meeting needs of the present and future. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:528-534. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.529.

4. Wang ES, Velásquez ST, Smith CJ, et al. Triaging inpatient admissions: an opportunity for resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2019; 34(5):754-757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04882-2.

5. Briones A, Markoff B, Kathuria N, et al. A model of a hospitalist role in the care of admitted patients in the emergency department. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):360-364. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.636.

6. Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:266-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30431.x.

7. Howell E, Bessman E, Marshall R, Wright S. Hospitalist bed management effecting throughput from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2010;25:184-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.08.004.

8. Chadaga SR, Shockley L, Keniston A, et al. Hospitalist-led medicine emergency department team: associations with throughput, timeliness of patient care, and satisfaction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:562-566. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1957.

9. Braun, V. Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

10. Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors influencing hospital admission of non-critically ill patients presenting to the emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8.

11. Patel KK, Vakharia N, Pile J, Howell EH, Rothberg MB. Preventable admissions on a general medicine service: prevalence, causes and comparison with AHRQ prevention quality indicators-a cross-sectional analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):597-601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3615-4.

12. Daniels LM1, Sorita A2, Kashiwagi DT, et al. Characterizing potentially preventable admissions: a mixed methods study of rates, associated factors, outcomes, and physician decision-making. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):737-744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4285-6.

13. Howard-Anderson J, Lonowski S, Vangala S, Tseng CH, Busuttil A, Afsar-Manesh N. Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870-1872. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4782.

14. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB, Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1907

Hospital medicine has grown dramatically over the past 20 years.1,2 A recent survey regarding hospitalists’ clinical roles showed an expansion to triaging emergency department (ED) medical admissions and transfers from outside hospitals.3 From the hospitalist perspective, triaging involves the evaluation of patients for potential admission.4 With scrutiny on ED metrics, such as wait times (https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html), health system administrators have heightened expectations for efficient patient flow, which increasingly falls to hospitalists.5-7

Despite the growth in hospitalists’ triagist activities, there has been little formal assessment of their role. We hypothesized that this role differs from inpatient care in significant ways.6-8 We sought to describe the triagist role in adult academic inpatient medicine settings to understand the responsibilities and skill set required.

METHODS

Ten academic medical center (AMC) sites were recruited from Research Committee session attendees at the 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine national meeting and the 2014 Society of General Internal Medicine southern regional meeting. The AMCs were geographically diverse: three Western, two Midwestern, two Southern, one Northeastern, and two Southeastern. Site representatives were identified and completed a web-based questionnaire about their AMC (see Appendix 1 for the information collected). Clarifications regarding survey responses were performed via conference calls between the authors (STV, ESW) and site representatives.

Hospitalist Survey

In January 2018, surveys were sent to 583 physicians who worked as triagists. Participants received an anonymous 28-item RedCap survey by e-mail and were sent up to five reminder e-mails over six weeks (see Appendix 2 for the questions analyzed in this paper). Respondents were given the option to be entered in a gift card drawing.

Demographic information and individual workflow/practices were obtained. A 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) was used to assess hospitalists’ concurrence with current providers (eg, ED, clinic providers) regarding the management and whether patients must meet the utilization management (UM) criteria for admission. Time estimates used 5% increments and were categorized into four frequency categories based on the local modes provided in responses: Seldom (0%-10%), Occasional (15%-35%), Half-the-Time (40%-60%), and Frequently (65%-100%). Free text responses on effective/ineffective triagist qualities were elicited. Responses were included for analysis if at least 70% of questions were completed.

Data Analysis

Quantitative

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences across AMCs in the time spent on in-person evaluation and communication. Weighting, based on the ratio of hospitalists to survey respondents at each AMC, was used to calculate the average institutional percentages across the study sample.

Qualitative

Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis.9 Three independent reviewers (STV, JC, ESW) read, analyzed, and grouped the responses by codes. Codes were then assessed for overlap and grouped into themes by one reviewer (STV). A table of themes with supporting quotes and the number of mentions was subsequently developed by all three reviewers. Similar themes were combined to create domains. The domains were reviewed by the steering committee members to create a consensus description (Appendix 3).

The University of Texas Health San Antonio’s Institutional Review Board and participating institutions approved the study as exempt.

RESULTS

Site Characteristics

Representatives from 10 AMCs reported data on a range of one to four hospitals for a total of 22 hospitals. The median reported that the number of medical patients admitted in a 24-hour period was 31-40 (range, 11-20 to >50). The median group size of hospitalists was 41-50 (range, 0-10 to >70).

The survey response rate was 40% (n = 235), ranging from 9%-70% between institutions. Self-identified female hospitalists accounted for 52% of respondents. Four percent were 25-29 years old, 66% were 30-39 years old, 24% were 40-49 years old, and 6% were ≥50 years old. The average clinical time spent as a triagist was 16%.

Description of Triagist Activities

The activities identified by the majority of respondents across all sites included transferring patients within the hospital (73%), and assessing/approving patient transfers from outside hospitals and clinics (82%). Internal transfer activities reported by >50% of respondents included allocating patients within the hospital or bed capacity coordination, assessing intensive care unit transfers, assigning ED admissions, and consulting other services. The ED accounted for an average of 55% of calls received. Respondents also reported being involved with the documentation related to these activities.

Similarities and Differences across AMCs

Two AMCs did not have a dedicated triagist; instead, physicians supervised residents and advanced practice providers. Among the eight sites with triagists, triaging was predominantly done by faculty physicians contacted via pagers. At seven of these sites, 100% of hospitalists worked as triagists. The triage service was covered by faculty physicians from 8-24 hours per day.

Bed boards and transfer centers staffed by registered nurses, nurse coordinators, house supervisors, or physicians were common support systems, though this infrastructure was organized differently across institutions. A UM review before admission was performed at three institutions 24 hours/day. The remaining institutions reviewed patients retrospectively.

Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists across all sites “Disagreed” or “Strongly disagreed” that a patient must meet UM criteria for admission. Forty-two percent had “Frequent” different opinions regarding patient management than the consulting provider.

Triagist and current provider communication practices varied widely across AMCs (Figure). There was significant variability in verbal communication (P = .02), with >70% of respondents at two AMCs reporting verbal communication at least half the time, but <30% reporting this frequency at two other AMCs. Respondents reported variable use of electronic communication (ie, notes/orders in the electronic health record) across AMCs (

The practice of evaluating patients in person also varied significantly across AMCs (P < .0001, Figure). Across hospitalists, only 28% see patients in person about “Half-the-Time” or more.

Differences within AMCs

Variability within AMCs was greatest for the rate of verbal communication practices, with a typical interquartile range (IQR) of 20% to 90% among the hospitalists within a given AMC and for the rate of electronic communication with a typical IQR of 0% to 50%. For other survey questions, the IQR was typically 15 to 20 percentage points.

Thematic Analysis

We received 207 and 203 responses (88% and 86%, respectively) to the open-ended questions “What qualities does an effective triagist have?’ and ‘What qualities make a triagist ineffective?” We identified 22 themes for effective and ineffective qualities, which were grouped into seven domains (Table). All themes had at least three mentions by respondents. The three most frequently mentioned themes, communication skills, efficiency, and systems knowledge, had greater than 60 mentions.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the triagist role at 10 AMCs describes critical triagist functions and identifies key findings across and within AMCs. Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists reported admitting patients even when the patient did not meet the admission criteria, consistent with previous research demonstrating the influence of factors other than clinical disease severity on triage decisions.10 However, preventable admissions remain a hospital-level quality metric.11,12 Triagists must often balance each patient’s circumstances with the complexities of the system. Juggling the competing demands of the system while providing patient-centered care can be challenging and may explain why attending physicians are more frequently filling this role.13

Local context/culture is likely to play a role in the variation across sites; however, compensation for the time spent may also be a factor. If triage activities are not reimbursable, this could lead to less documentation and a lower likelihood that patients are evaluated in person.14 This reason may also explain why all hospitalists were required to serve as a triagist at most sites.

Currently, no consensus definition of the triagist role has been developed. Our results demonstrate that this role is heterogeneous and grounded in the local healthcare system practices. We propose the following working definition of the triagist: a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting. A triagist should be equipped with a skill set that includes not only clinical knowledge but also emphasizes systems knowledge, awareness of others’ goals, efficiency, an ability to communicate effectively, and the knowledge of UM. We recommend that medical directors of hospitalist programs focus their attention on locally specific, systems-based skills development when orienting new hospitalists. The financial aspects of cost should be considered and delineated as well.

Our analysis is limited in several respects. Participant AMCs were not randomly chosen, but do represent a broad array of facility types, group size, and geographic regions. The low response rates at some AMCs may result in an inaccurate representation of those sites. Data was not obtained on hospitalists that did not respond to the survey; therefore, nonresponse bias may affect outcomes. This research used self-report rather than direct observation, which could be subject to recall and social desirability bias. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to nonacademic institutions.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalist role as triagist at AMCs emphasizes communication, organizational skills, efficiency, systems-based practice, and UM knowledge. Although we found significant variation across and within AMCs, internal transfer activities were common across programs. Hospitalist programs should focus on systems-based skills development to prepare hospitalists for the role. The skill set necessary for triagist responsibilities also has implications for internal medicine resident education.4 With increasing emphasis on value and system effectiveness in care delivery, further studies of the triagist role should be undertaken.

Acknowledgments

The TRIAGIST Collaborative Group consists of: Maralyssa Bann, MD, Andrew White, MD (University of Washington); Jagriti Chadha, MD (University of Kentucky); Joel Boggan, MD (Duke University); Sherwin Hsu, MD (UCLA); Jeff Liao, MD (Harvard Medical School); Tabatha Matthias, DO (University of Nebraska Medical Center); Tresa McNeal, MD (Scott and White Texas A&M); Roxana Naderi, MD, Khooshbu Shah, MD (University of Colorado); David Schmit, MD (University of Texas Health San Antonio); Manivannan Veerasamy, MD (Michigan State University).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the po

Hospital medicine has grown dramatically over the past 20 years.1,2 A recent survey regarding hospitalists’ clinical roles showed an expansion to triaging emergency department (ED) medical admissions and transfers from outside hospitals.3 From the hospitalist perspective, triaging involves the evaluation of patients for potential admission.4 With scrutiny on ED metrics, such as wait times (https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html), health system administrators have heightened expectations for efficient patient flow, which increasingly falls to hospitalists.5-7

Despite the growth in hospitalists’ triagist activities, there has been little formal assessment of their role. We hypothesized that this role differs from inpatient care in significant ways.6-8 We sought to describe the triagist role in adult academic inpatient medicine settings to understand the responsibilities and skill set required.

METHODS

Ten academic medical center (AMC) sites were recruited from Research Committee session attendees at the 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine national meeting and the 2014 Society of General Internal Medicine southern regional meeting. The AMCs were geographically diverse: three Western, two Midwestern, two Southern, one Northeastern, and two Southeastern. Site representatives were identified and completed a web-based questionnaire about their AMC (see Appendix 1 for the information collected). Clarifications regarding survey responses were performed via conference calls between the authors (STV, ESW) and site representatives.

Hospitalist Survey

In January 2018, surveys were sent to 583 physicians who worked as triagists. Participants received an anonymous 28-item RedCap survey by e-mail and were sent up to five reminder e-mails over six weeks (see Appendix 2 for the questions analyzed in this paper). Respondents were given the option to be entered in a gift card drawing.

Demographic information and individual workflow/practices were obtained. A 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) was used to assess hospitalists’ concurrence with current providers (eg, ED, clinic providers) regarding the management and whether patients must meet the utilization management (UM) criteria for admission. Time estimates used 5% increments and were categorized into four frequency categories based on the local modes provided in responses: Seldom (0%-10%), Occasional (15%-35%), Half-the-Time (40%-60%), and Frequently (65%-100%). Free text responses on effective/ineffective triagist qualities were elicited. Responses were included for analysis if at least 70% of questions were completed.

Data Analysis

Quantitative

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences across AMCs in the time spent on in-person evaluation and communication. Weighting, based on the ratio of hospitalists to survey respondents at each AMC, was used to calculate the average institutional percentages across the study sample.

Qualitative

Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis.9 Three independent reviewers (STV, JC, ESW) read, analyzed, and grouped the responses by codes. Codes were then assessed for overlap and grouped into themes by one reviewer (STV). A table of themes with supporting quotes and the number of mentions was subsequently developed by all three reviewers. Similar themes were combined to create domains. The domains were reviewed by the steering committee members to create a consensus description (Appendix 3).

The University of Texas Health San Antonio’s Institutional Review Board and participating institutions approved the study as exempt.

RESULTS

Site Characteristics

Representatives from 10 AMCs reported data on a range of one to four hospitals for a total of 22 hospitals. The median reported that the number of medical patients admitted in a 24-hour period was 31-40 (range, 11-20 to >50). The median group size of hospitalists was 41-50 (range, 0-10 to >70).

The survey response rate was 40% (n = 235), ranging from 9%-70% between institutions. Self-identified female hospitalists accounted for 52% of respondents. Four percent were 25-29 years old, 66% were 30-39 years old, 24% were 40-49 years old, and 6% were ≥50 years old. The average clinical time spent as a triagist was 16%.

Description of Triagist Activities

The activities identified by the majority of respondents across all sites included transferring patients within the hospital (73%), and assessing/approving patient transfers from outside hospitals and clinics (82%). Internal transfer activities reported by >50% of respondents included allocating patients within the hospital or bed capacity coordination, assessing intensive care unit transfers, assigning ED admissions, and consulting other services. The ED accounted for an average of 55% of calls received. Respondents also reported being involved with the documentation related to these activities.

Similarities and Differences across AMCs

Two AMCs did not have a dedicated triagist; instead, physicians supervised residents and advanced practice providers. Among the eight sites with triagists, triaging was predominantly done by faculty physicians contacted via pagers. At seven of these sites, 100% of hospitalists worked as triagists. The triage service was covered by faculty physicians from 8-24 hours per day.

Bed boards and transfer centers staffed by registered nurses, nurse coordinators, house supervisors, or physicians were common support systems, though this infrastructure was organized differently across institutions. A UM review before admission was performed at three institutions 24 hours/day. The remaining institutions reviewed patients retrospectively.

Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists across all sites “Disagreed” or “Strongly disagreed” that a patient must meet UM criteria for admission. Forty-two percent had “Frequent” different opinions regarding patient management than the consulting provider.

Triagist and current provider communication practices varied widely across AMCs (Figure). There was significant variability in verbal communication (P = .02), with >70% of respondents at two AMCs reporting verbal communication at least half the time, but <30% reporting this frequency at two other AMCs. Respondents reported variable use of electronic communication (ie, notes/orders in the electronic health record) across AMCs (

The practice of evaluating patients in person also varied significantly across AMCs (P < .0001, Figure). Across hospitalists, only 28% see patients in person about “Half-the-Time” or more.

Differences within AMCs

Variability within AMCs was greatest for the rate of verbal communication practices, with a typical interquartile range (IQR) of 20% to 90% among the hospitalists within a given AMC and for the rate of electronic communication with a typical IQR of 0% to 50%. For other survey questions, the IQR was typically 15 to 20 percentage points.

Thematic Analysis

We received 207 and 203 responses (88% and 86%, respectively) to the open-ended questions “What qualities does an effective triagist have?’ and ‘What qualities make a triagist ineffective?” We identified 22 themes for effective and ineffective qualities, which were grouped into seven domains (Table). All themes had at least three mentions by respondents. The three most frequently mentioned themes, communication skills, efficiency, and systems knowledge, had greater than 60 mentions.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the triagist role at 10 AMCs describes critical triagist functions and identifies key findings across and within AMCs. Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists reported admitting patients even when the patient did not meet the admission criteria, consistent with previous research demonstrating the influence of factors other than clinical disease severity on triage decisions.10 However, preventable admissions remain a hospital-level quality metric.11,12 Triagists must often balance each patient’s circumstances with the complexities of the system. Juggling the competing demands of the system while providing patient-centered care can be challenging and may explain why attending physicians are more frequently filling this role.13

Local context/culture is likely to play a role in the variation across sites; however, compensation for the time spent may also be a factor. If triage activities are not reimbursable, this could lead to less documentation and a lower likelihood that patients are evaluated in person.14 This reason may also explain why all hospitalists were required to serve as a triagist at most sites.

Currently, no consensus definition of the triagist role has been developed. Our results demonstrate that this role is heterogeneous and grounded in the local healthcare system practices. We propose the following working definition of the triagist: a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting. A triagist should be equipped with a skill set that includes not only clinical knowledge but also emphasizes systems knowledge, awareness of others’ goals, efficiency, an ability to communicate effectively, and the knowledge of UM. We recommend that medical directors of hospitalist programs focus their attention on locally specific, systems-based skills development when orienting new hospitalists. The financial aspects of cost should be considered and delineated as well.

Our analysis is limited in several respects. Participant AMCs were not randomly chosen, but do represent a broad array of facility types, group size, and geographic regions. The low response rates at some AMCs may result in an inaccurate representation of those sites. Data was not obtained on hospitalists that did not respond to the survey; therefore, nonresponse bias may affect outcomes. This research used self-report rather than direct observation, which could be subject to recall and social desirability bias. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to nonacademic institutions.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalist role as triagist at AMCs emphasizes communication, organizational skills, efficiency, systems-based practice, and UM knowledge. Although we found significant variation across and within AMCs, internal transfer activities were common across programs. Hospitalist programs should focus on systems-based skills development to prepare hospitalists for the role. The skill set necessary for triagist responsibilities also has implications for internal medicine resident education.4 With increasing emphasis on value and system effectiveness in care delivery, further studies of the triagist role should be undertaken.

Acknowledgments

The TRIAGIST Collaborative Group consists of: Maralyssa Bann, MD, Andrew White, MD (University of Washington); Jagriti Chadha, MD (University of Kentucky); Joel Boggan, MD (Duke University); Sherwin Hsu, MD (UCLA); Jeff Liao, MD (Harvard Medical School); Tabatha Matthias, DO (University of Nebraska Medical Center); Tresa McNeal, MD (Scott and White Texas A&M); Roxana Naderi, MD, Khooshbu Shah, MD (University of Colorado); David Schmit, MD (University of Texas Health San Antonio); Manivannan Veerasamy, MD (Michigan State University).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the po

1. Kisuule F, Howell EE. Hospitalists and their impact on quality, patient safety, and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015; 42(3):433-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2015.05.003.

2. Wachter, RM, Goldman, L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11): 1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

3. Vasilevskis EE, Knebel RJ, Wachter RM, Auerbach AD. California hospital leaders’ views of hospitalists: meeting needs of the present and future. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:528-534. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.529.

4. Wang ES, Velásquez ST, Smith CJ, et al. Triaging inpatient admissions: an opportunity for resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2019; 34(5):754-757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04882-2.

5. Briones A, Markoff B, Kathuria N, et al. A model of a hospitalist role in the care of admitted patients in the emergency department. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):360-364. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.636.

6. Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:266-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30431.x.

7. Howell E, Bessman E, Marshall R, Wright S. Hospitalist bed management effecting throughput from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2010;25:184-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.08.004.

8. Chadaga SR, Shockley L, Keniston A, et al. Hospitalist-led medicine emergency department team: associations with throughput, timeliness of patient care, and satisfaction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:562-566. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1957.

9. Braun, V. Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

10. Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors influencing hospital admission of non-critically ill patients presenting to the emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8.

11. Patel KK, Vakharia N, Pile J, Howell EH, Rothberg MB. Preventable admissions on a general medicine service: prevalence, causes and comparison with AHRQ prevention quality indicators-a cross-sectional analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):597-601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3615-4.

12. Daniels LM1, Sorita A2, Kashiwagi DT, et al. Characterizing potentially preventable admissions: a mixed methods study of rates, associated factors, outcomes, and physician decision-making. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):737-744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4285-6.

13. Howard-Anderson J, Lonowski S, Vangala S, Tseng CH, Busuttil A, Afsar-Manesh N. Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870-1872. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4782.

14. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB, Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1907

1. Kisuule F, Howell EE. Hospitalists and their impact on quality, patient safety, and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015; 42(3):433-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2015.05.003.

2. Wachter, RM, Goldman, L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11): 1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

3. Vasilevskis EE, Knebel RJ, Wachter RM, Auerbach AD. California hospital leaders’ views of hospitalists: meeting needs of the present and future. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:528-534. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.529.

4. Wang ES, Velásquez ST, Smith CJ, et al. Triaging inpatient admissions: an opportunity for resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2019; 34(5):754-757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04882-2.

5. Briones A, Markoff B, Kathuria N, et al. A model of a hospitalist role in the care of admitted patients in the emergency department. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):360-364. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.636.

6. Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:266-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30431.x.

7. Howell E, Bessman E, Marshall R, Wright S. Hospitalist bed management effecting throughput from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2010;25:184-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.08.004.

8. Chadaga SR, Shockley L, Keniston A, et al. Hospitalist-led medicine emergency department team: associations with throughput, timeliness of patient care, and satisfaction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:562-566. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1957.

9. Braun, V. Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

10. Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors influencing hospital admission of non-critically ill patients presenting to the emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8.

11. Patel KK, Vakharia N, Pile J, Howell EH, Rothberg MB. Preventable admissions on a general medicine service: prevalence, causes and comparison with AHRQ prevention quality indicators-a cross-sectional analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):597-601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3615-4.

12. Daniels LM1, Sorita A2, Kashiwagi DT, et al. Characterizing potentially preventable admissions: a mixed methods study of rates, associated factors, outcomes, and physician decision-making. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):737-744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4285-6.

13. Howard-Anderson J, Lonowski S, Vangala S, Tseng CH, Busuttil A, Afsar-Manesh N. Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870-1872. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4782.

14. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB, Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1907

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine