User login

Hospitalists as Triagists: Description of the Triagist Role across Academic Medical Centers

Hospital medicine has grown dramatically over the past 20 years.1,2 A recent survey regarding hospitalists’ clinical roles showed an expansion to triaging emergency department (ED) medical admissions and transfers from outside hospitals.3 From the hospitalist perspective, triaging involves the evaluation of patients for potential admission.4 With scrutiny on ED metrics, such as wait times (https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html), health system administrators have heightened expectations for efficient patient flow, which increasingly falls to hospitalists.5-7

Despite the growth in hospitalists’ triagist activities, there has been little formal assessment of their role. We hypothesized that this role differs from inpatient care in significant ways.6-8 We sought to describe the triagist role in adult academic inpatient medicine settings to understand the responsibilities and skill set required.

METHODS

Ten academic medical center (AMC) sites were recruited from Research Committee session attendees at the 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine national meeting and the 2014 Society of General Internal Medicine southern regional meeting. The AMCs were geographically diverse: three Western, two Midwestern, two Southern, one Northeastern, and two Southeastern. Site representatives were identified and completed a web-based questionnaire about their AMC (see Appendix 1 for the information collected). Clarifications regarding survey responses were performed via conference calls between the authors (STV, ESW) and site representatives.

Hospitalist Survey

In January 2018, surveys were sent to 583 physicians who worked as triagists. Participants received an anonymous 28-item RedCap survey by e-mail and were sent up to five reminder e-mails over six weeks (see Appendix 2 for the questions analyzed in this paper). Respondents were given the option to be entered in a gift card drawing.

Demographic information and individual workflow/practices were obtained. A 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) was used to assess hospitalists’ concurrence with current providers (eg, ED, clinic providers) regarding the management and whether patients must meet the utilization management (UM) criteria for admission. Time estimates used 5% increments and were categorized into four frequency categories based on the local modes provided in responses: Seldom (0%-10%), Occasional (15%-35%), Half-the-Time (40%-60%), and Frequently (65%-100%). Free text responses on effective/ineffective triagist qualities were elicited. Responses were included for analysis if at least 70% of questions were completed.

Data Analysis

Quantitative

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences across AMCs in the time spent on in-person evaluation and communication. Weighting, based on the ratio of hospitalists to survey respondents at each AMC, was used to calculate the average institutional percentages across the study sample.

Qualitative

Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis.9 Three independent reviewers (STV, JC, ESW) read, analyzed, and grouped the responses by codes. Codes were then assessed for overlap and grouped into themes by one reviewer (STV). A table of themes with supporting quotes and the number of mentions was subsequently developed by all three reviewers. Similar themes were combined to create domains. The domains were reviewed by the steering committee members to create a consensus description (Appendix 3).

The University of Texas Health San Antonio’s Institutional Review Board and participating institutions approved the study as exempt.

RESULTS

Site Characteristics

Representatives from 10 AMCs reported data on a range of one to four hospitals for a total of 22 hospitals. The median reported that the number of medical patients admitted in a 24-hour period was 31-40 (range, 11-20 to >50). The median group size of hospitalists was 41-50 (range, 0-10 to >70).

The survey response rate was 40% (n = 235), ranging from 9%-70% between institutions. Self-identified female hospitalists accounted for 52% of respondents. Four percent were 25-29 years old, 66% were 30-39 years old, 24% were 40-49 years old, and 6% were ≥50 years old. The average clinical time spent as a triagist was 16%.

Description of Triagist Activities

The activities identified by the majority of respondents across all sites included transferring patients within the hospital (73%), and assessing/approving patient transfers from outside hospitals and clinics (82%). Internal transfer activities reported by >50% of respondents included allocating patients within the hospital or bed capacity coordination, assessing intensive care unit transfers, assigning ED admissions, and consulting other services. The ED accounted for an average of 55% of calls received. Respondents also reported being involved with the documentation related to these activities.

Similarities and Differences across AMCs

Two AMCs did not have a dedicated triagist; instead, physicians supervised residents and advanced practice providers. Among the eight sites with triagists, triaging was predominantly done by faculty physicians contacted via pagers. At seven of these sites, 100% of hospitalists worked as triagists. The triage service was covered by faculty physicians from 8-24 hours per day.

Bed boards and transfer centers staffed by registered nurses, nurse coordinators, house supervisors, or physicians were common support systems, though this infrastructure was organized differently across institutions. A UM review before admission was performed at three institutions 24 hours/day. The remaining institutions reviewed patients retrospectively.

Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists across all sites “Disagreed” or “Strongly disagreed” that a patient must meet UM criteria for admission. Forty-two percent had “Frequent” different opinions regarding patient management than the consulting provider.

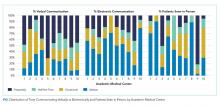

Triagist and current provider communication practices varied widely across AMCs (Figure). There was significant variability in verbal communication (P = .02), with >70% of respondents at two AMCs reporting verbal communication at least half the time, but <30% reporting this frequency at two other AMCs. Respondents reported variable use of electronic communication (ie, notes/orders in the electronic health record) across AMCs (

The practice of evaluating patients in person also varied significantly across AMCs (P < .0001, Figure). Across hospitalists, only 28% see patients in person about “Half-the-Time” or more.

Differences within AMCs

Variability within AMCs was greatest for the rate of verbal communication practices, with a typical interquartile range (IQR) of 20% to 90% among the hospitalists within a given AMC and for the rate of electronic communication with a typical IQR of 0% to 50%. For other survey questions, the IQR was typically 15 to 20 percentage points.

Thematic Analysis

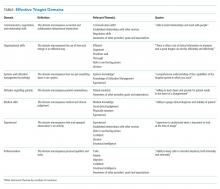

We received 207 and 203 responses (88% and 86%, respectively) to the open-ended questions “What qualities does an effective triagist have?’ and ‘What qualities make a triagist ineffective?” We identified 22 themes for effective and ineffective qualities, which were grouped into seven domains (Table). All themes had at least three mentions by respondents. The three most frequently mentioned themes, communication skills, efficiency, and systems knowledge, had greater than 60 mentions.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the triagist role at 10 AMCs describes critical triagist functions and identifies key findings across and within AMCs. Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists reported admitting patients even when the patient did not meet the admission criteria, consistent with previous research demonstrating the influence of factors other than clinical disease severity on triage decisions.10 However, preventable admissions remain a hospital-level quality metric.11,12 Triagists must often balance each patient’s circumstances with the complexities of the system. Juggling the competing demands of the system while providing patient-centered care can be challenging and may explain why attending physicians are more frequently filling this role.13

Local context/culture is likely to play a role in the variation across sites; however, compensation for the time spent may also be a factor. If triage activities are not reimbursable, this could lead to less documentation and a lower likelihood that patients are evaluated in person.14 This reason may also explain why all hospitalists were required to serve as a triagist at most sites.

Currently, no consensus definition of the triagist role has been developed. Our results demonstrate that this role is heterogeneous and grounded in the local healthcare system practices. We propose the following working definition of the triagist: a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting. A triagist should be equipped with a skill set that includes not only clinical knowledge but also emphasizes systems knowledge, awareness of others’ goals, efficiency, an ability to communicate effectively, and the knowledge of UM. We recommend that medical directors of hospitalist programs focus their attention on locally specific, systems-based skills development when orienting new hospitalists. The financial aspects of cost should be considered and delineated as well.

Our analysis is limited in several respects. Participant AMCs were not randomly chosen, but do represent a broad array of facility types, group size, and geographic regions. The low response rates at some AMCs may result in an inaccurate representation of those sites. Data was not obtained on hospitalists that did not respond to the survey; therefore, nonresponse bias may affect outcomes. This research used self-report rather than direct observation, which could be subject to recall and social desirability bias. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to nonacademic institutions.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalist role as triagist at AMCs emphasizes communication, organizational skills, efficiency, systems-based practice, and UM knowledge. Although we found significant variation across and within AMCs, internal transfer activities were common across programs. Hospitalist programs should focus on systems-based skills development to prepare hospitalists for the role. The skill set necessary for triagist responsibilities also has implications for internal medicine resident education.4 With increasing emphasis on value and system effectiveness in care delivery, further studies of the triagist role should be undertaken.

Acknowledgments

The TRIAGIST Collaborative Group consists of: Maralyssa Bann, MD, Andrew White, MD (University of Washington); Jagriti Chadha, MD (University of Kentucky); Joel Boggan, MD (Duke University); Sherwin Hsu, MD (UCLA); Jeff Liao, MD (Harvard Medical School); Tabatha Matthias, DO (University of Nebraska Medical Center); Tresa McNeal, MD (Scott and White Texas A&M); Roxana Naderi, MD, Khooshbu Shah, MD (University of Colorado); David Schmit, MD (University of Texas Health San Antonio); Manivannan Veerasamy, MD (Michigan State University).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the po

1. Kisuule F, Howell EE. Hospitalists and their impact on quality, patient safety, and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015; 42(3):433-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2015.05.003.

2. Wachter, RM, Goldman, L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11): 1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

3. Vasilevskis EE, Knebel RJ, Wachter RM, Auerbach AD. California hospital leaders’ views of hospitalists: meeting needs of the present and future. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:528-534. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.529.

4. Wang ES, Velásquez ST, Smith CJ, et al. Triaging inpatient admissions: an opportunity for resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2019; 34(5):754-757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04882-2.

5. Briones A, Markoff B, Kathuria N, et al. A model of a hospitalist role in the care of admitted patients in the emergency department. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):360-364. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.636.

6. Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:266-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30431.x.

7. Howell E, Bessman E, Marshall R, Wright S. Hospitalist bed management effecting throughput from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2010;25:184-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.08.004.

8. Chadaga SR, Shockley L, Keniston A, et al. Hospitalist-led medicine emergency department team: associations with throughput, timeliness of patient care, and satisfaction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:562-566. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1957.

9. Braun, V. Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

10. Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors influencing hospital admission of non-critically ill patients presenting to the emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8.

11. Patel KK, Vakharia N, Pile J, Howell EH, Rothberg MB. Preventable admissions on a general medicine service: prevalence, causes and comparison with AHRQ prevention quality indicators-a cross-sectional analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):597-601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3615-4.

12. Daniels LM1, Sorita A2, Kashiwagi DT, et al. Characterizing potentially preventable admissions: a mixed methods study of rates, associated factors, outcomes, and physician decision-making. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):737-744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4285-6.

13. Howard-Anderson J, Lonowski S, Vangala S, Tseng CH, Busuttil A, Afsar-Manesh N. Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870-1872. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4782.

14. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB, Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1907

Hospital medicine has grown dramatically over the past 20 years.1,2 A recent survey regarding hospitalists’ clinical roles showed an expansion to triaging emergency department (ED) medical admissions and transfers from outside hospitals.3 From the hospitalist perspective, triaging involves the evaluation of patients for potential admission.4 With scrutiny on ED metrics, such as wait times (https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html), health system administrators have heightened expectations for efficient patient flow, which increasingly falls to hospitalists.5-7

Despite the growth in hospitalists’ triagist activities, there has been little formal assessment of their role. We hypothesized that this role differs from inpatient care in significant ways.6-8 We sought to describe the triagist role in adult academic inpatient medicine settings to understand the responsibilities and skill set required.

METHODS

Ten academic medical center (AMC) sites were recruited from Research Committee session attendees at the 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine national meeting and the 2014 Society of General Internal Medicine southern regional meeting. The AMCs were geographically diverse: three Western, two Midwestern, two Southern, one Northeastern, and two Southeastern. Site representatives were identified and completed a web-based questionnaire about their AMC (see Appendix 1 for the information collected). Clarifications regarding survey responses were performed via conference calls between the authors (STV, ESW) and site representatives.

Hospitalist Survey

In January 2018, surveys were sent to 583 physicians who worked as triagists. Participants received an anonymous 28-item RedCap survey by e-mail and were sent up to five reminder e-mails over six weeks (see Appendix 2 for the questions analyzed in this paper). Respondents were given the option to be entered in a gift card drawing.

Demographic information and individual workflow/practices were obtained. A 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) was used to assess hospitalists’ concurrence with current providers (eg, ED, clinic providers) regarding the management and whether patients must meet the utilization management (UM) criteria for admission. Time estimates used 5% increments and were categorized into four frequency categories based on the local modes provided in responses: Seldom (0%-10%), Occasional (15%-35%), Half-the-Time (40%-60%), and Frequently (65%-100%). Free text responses on effective/ineffective triagist qualities were elicited. Responses were included for analysis if at least 70% of questions were completed.

Data Analysis

Quantitative

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences across AMCs in the time spent on in-person evaluation and communication. Weighting, based on the ratio of hospitalists to survey respondents at each AMC, was used to calculate the average institutional percentages across the study sample.

Qualitative

Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis.9 Three independent reviewers (STV, JC, ESW) read, analyzed, and grouped the responses by codes. Codes were then assessed for overlap and grouped into themes by one reviewer (STV). A table of themes with supporting quotes and the number of mentions was subsequently developed by all three reviewers. Similar themes were combined to create domains. The domains were reviewed by the steering committee members to create a consensus description (Appendix 3).

The University of Texas Health San Antonio’s Institutional Review Board and participating institutions approved the study as exempt.

RESULTS

Site Characteristics

Representatives from 10 AMCs reported data on a range of one to four hospitals for a total of 22 hospitals. The median reported that the number of medical patients admitted in a 24-hour period was 31-40 (range, 11-20 to >50). The median group size of hospitalists was 41-50 (range, 0-10 to >70).

The survey response rate was 40% (n = 235), ranging from 9%-70% between institutions. Self-identified female hospitalists accounted for 52% of respondents. Four percent were 25-29 years old, 66% were 30-39 years old, 24% were 40-49 years old, and 6% were ≥50 years old. The average clinical time spent as a triagist was 16%.

Description of Triagist Activities

The activities identified by the majority of respondents across all sites included transferring patients within the hospital (73%), and assessing/approving patient transfers from outside hospitals and clinics (82%). Internal transfer activities reported by >50% of respondents included allocating patients within the hospital or bed capacity coordination, assessing intensive care unit transfers, assigning ED admissions, and consulting other services. The ED accounted for an average of 55% of calls received. Respondents also reported being involved with the documentation related to these activities.

Similarities and Differences across AMCs

Two AMCs did not have a dedicated triagist; instead, physicians supervised residents and advanced practice providers. Among the eight sites with triagists, triaging was predominantly done by faculty physicians contacted via pagers. At seven of these sites, 100% of hospitalists worked as triagists. The triage service was covered by faculty physicians from 8-24 hours per day.

Bed boards and transfer centers staffed by registered nurses, nurse coordinators, house supervisors, or physicians were common support systems, though this infrastructure was organized differently across institutions. A UM review before admission was performed at three institutions 24 hours/day. The remaining institutions reviewed patients retrospectively.

Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists across all sites “Disagreed” or “Strongly disagreed” that a patient must meet UM criteria for admission. Forty-two percent had “Frequent” different opinions regarding patient management than the consulting provider.

Triagist and current provider communication practices varied widely across AMCs (Figure). There was significant variability in verbal communication (P = .02), with >70% of respondents at two AMCs reporting verbal communication at least half the time, but <30% reporting this frequency at two other AMCs. Respondents reported variable use of electronic communication (ie, notes/orders in the electronic health record) across AMCs (

The practice of evaluating patients in person also varied significantly across AMCs (P < .0001, Figure). Across hospitalists, only 28% see patients in person about “Half-the-Time” or more.

Differences within AMCs

Variability within AMCs was greatest for the rate of verbal communication practices, with a typical interquartile range (IQR) of 20% to 90% among the hospitalists within a given AMC and for the rate of electronic communication with a typical IQR of 0% to 50%. For other survey questions, the IQR was typically 15 to 20 percentage points.

Thematic Analysis

We received 207 and 203 responses (88% and 86%, respectively) to the open-ended questions “What qualities does an effective triagist have?’ and ‘What qualities make a triagist ineffective?” We identified 22 themes for effective and ineffective qualities, which were grouped into seven domains (Table). All themes had at least three mentions by respondents. The three most frequently mentioned themes, communication skills, efficiency, and systems knowledge, had greater than 60 mentions.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the triagist role at 10 AMCs describes critical triagist functions and identifies key findings across and within AMCs. Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists reported admitting patients even when the patient did not meet the admission criteria, consistent with previous research demonstrating the influence of factors other than clinical disease severity on triage decisions.10 However, preventable admissions remain a hospital-level quality metric.11,12 Triagists must often balance each patient’s circumstances with the complexities of the system. Juggling the competing demands of the system while providing patient-centered care can be challenging and may explain why attending physicians are more frequently filling this role.13

Local context/culture is likely to play a role in the variation across sites; however, compensation for the time spent may also be a factor. If triage activities are not reimbursable, this could lead to less documentation and a lower likelihood that patients are evaluated in person.14 This reason may also explain why all hospitalists were required to serve as a triagist at most sites.

Currently, no consensus definition of the triagist role has been developed. Our results demonstrate that this role is heterogeneous and grounded in the local healthcare system practices. We propose the following working definition of the triagist: a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting. A triagist should be equipped with a skill set that includes not only clinical knowledge but also emphasizes systems knowledge, awareness of others’ goals, efficiency, an ability to communicate effectively, and the knowledge of UM. We recommend that medical directors of hospitalist programs focus their attention on locally specific, systems-based skills development when orienting new hospitalists. The financial aspects of cost should be considered and delineated as well.

Our analysis is limited in several respects. Participant AMCs were not randomly chosen, but do represent a broad array of facility types, group size, and geographic regions. The low response rates at some AMCs may result in an inaccurate representation of those sites. Data was not obtained on hospitalists that did not respond to the survey; therefore, nonresponse bias may affect outcomes. This research used self-report rather than direct observation, which could be subject to recall and social desirability bias. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to nonacademic institutions.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalist role as triagist at AMCs emphasizes communication, organizational skills, efficiency, systems-based practice, and UM knowledge. Although we found significant variation across and within AMCs, internal transfer activities were common across programs. Hospitalist programs should focus on systems-based skills development to prepare hospitalists for the role. The skill set necessary for triagist responsibilities also has implications for internal medicine resident education.4 With increasing emphasis on value and system effectiveness in care delivery, further studies of the triagist role should be undertaken.

Acknowledgments

The TRIAGIST Collaborative Group consists of: Maralyssa Bann, MD, Andrew White, MD (University of Washington); Jagriti Chadha, MD (University of Kentucky); Joel Boggan, MD (Duke University); Sherwin Hsu, MD (UCLA); Jeff Liao, MD (Harvard Medical School); Tabatha Matthias, DO (University of Nebraska Medical Center); Tresa McNeal, MD (Scott and White Texas A&M); Roxana Naderi, MD, Khooshbu Shah, MD (University of Colorado); David Schmit, MD (University of Texas Health San Antonio); Manivannan Veerasamy, MD (Michigan State University).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the po

Hospital medicine has grown dramatically over the past 20 years.1,2 A recent survey regarding hospitalists’ clinical roles showed an expansion to triaging emergency department (ED) medical admissions and transfers from outside hospitals.3 From the hospitalist perspective, triaging involves the evaluation of patients for potential admission.4 With scrutiny on ED metrics, such as wait times (https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html), health system administrators have heightened expectations for efficient patient flow, which increasingly falls to hospitalists.5-7

Despite the growth in hospitalists’ triagist activities, there has been little formal assessment of their role. We hypothesized that this role differs from inpatient care in significant ways.6-8 We sought to describe the triagist role in adult academic inpatient medicine settings to understand the responsibilities and skill set required.

METHODS

Ten academic medical center (AMC) sites were recruited from Research Committee session attendees at the 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine national meeting and the 2014 Society of General Internal Medicine southern regional meeting. The AMCs were geographically diverse: three Western, two Midwestern, two Southern, one Northeastern, and two Southeastern. Site representatives were identified and completed a web-based questionnaire about their AMC (see Appendix 1 for the information collected). Clarifications regarding survey responses were performed via conference calls between the authors (STV, ESW) and site representatives.

Hospitalist Survey

In January 2018, surveys were sent to 583 physicians who worked as triagists. Participants received an anonymous 28-item RedCap survey by e-mail and were sent up to five reminder e-mails over six weeks (see Appendix 2 for the questions analyzed in this paper). Respondents were given the option to be entered in a gift card drawing.

Demographic information and individual workflow/practices were obtained. A 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) was used to assess hospitalists’ concurrence with current providers (eg, ED, clinic providers) regarding the management and whether patients must meet the utilization management (UM) criteria for admission. Time estimates used 5% increments and were categorized into four frequency categories based on the local modes provided in responses: Seldom (0%-10%), Occasional (15%-35%), Half-the-Time (40%-60%), and Frequently (65%-100%). Free text responses on effective/ineffective triagist qualities were elicited. Responses were included for analysis if at least 70% of questions were completed.

Data Analysis

Quantitative

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences across AMCs in the time spent on in-person evaluation and communication. Weighting, based on the ratio of hospitalists to survey respondents at each AMC, was used to calculate the average institutional percentages across the study sample.

Qualitative

Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis.9 Three independent reviewers (STV, JC, ESW) read, analyzed, and grouped the responses by codes. Codes were then assessed for overlap and grouped into themes by one reviewer (STV). A table of themes with supporting quotes and the number of mentions was subsequently developed by all three reviewers. Similar themes were combined to create domains. The domains were reviewed by the steering committee members to create a consensus description (Appendix 3).

The University of Texas Health San Antonio’s Institutional Review Board and participating institutions approved the study as exempt.

RESULTS

Site Characteristics

Representatives from 10 AMCs reported data on a range of one to four hospitals for a total of 22 hospitals. The median reported that the number of medical patients admitted in a 24-hour period was 31-40 (range, 11-20 to >50). The median group size of hospitalists was 41-50 (range, 0-10 to >70).

The survey response rate was 40% (n = 235), ranging from 9%-70% between institutions. Self-identified female hospitalists accounted for 52% of respondents. Four percent were 25-29 years old, 66% were 30-39 years old, 24% were 40-49 years old, and 6% were ≥50 years old. The average clinical time spent as a triagist was 16%.

Description of Triagist Activities

The activities identified by the majority of respondents across all sites included transferring patients within the hospital (73%), and assessing/approving patient transfers from outside hospitals and clinics (82%). Internal transfer activities reported by >50% of respondents included allocating patients within the hospital or bed capacity coordination, assessing intensive care unit transfers, assigning ED admissions, and consulting other services. The ED accounted for an average of 55% of calls received. Respondents also reported being involved with the documentation related to these activities.

Similarities and Differences across AMCs

Two AMCs did not have a dedicated triagist; instead, physicians supervised residents and advanced practice providers. Among the eight sites with triagists, triaging was predominantly done by faculty physicians contacted via pagers. At seven of these sites, 100% of hospitalists worked as triagists. The triage service was covered by faculty physicians from 8-24 hours per day.

Bed boards and transfer centers staffed by registered nurses, nurse coordinators, house supervisors, or physicians were common support systems, though this infrastructure was organized differently across institutions. A UM review before admission was performed at three institutions 24 hours/day. The remaining institutions reviewed patients retrospectively.

Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists across all sites “Disagreed” or “Strongly disagreed” that a patient must meet UM criteria for admission. Forty-two percent had “Frequent” different opinions regarding patient management than the consulting provider.

Triagist and current provider communication practices varied widely across AMCs (Figure). There was significant variability in verbal communication (P = .02), with >70% of respondents at two AMCs reporting verbal communication at least half the time, but <30% reporting this frequency at two other AMCs. Respondents reported variable use of electronic communication (ie, notes/orders in the electronic health record) across AMCs (

The practice of evaluating patients in person also varied significantly across AMCs (P < .0001, Figure). Across hospitalists, only 28% see patients in person about “Half-the-Time” or more.

Differences within AMCs

Variability within AMCs was greatest for the rate of verbal communication practices, with a typical interquartile range (IQR) of 20% to 90% among the hospitalists within a given AMC and for the rate of electronic communication with a typical IQR of 0% to 50%. For other survey questions, the IQR was typically 15 to 20 percentage points.

Thematic Analysis

We received 207 and 203 responses (88% and 86%, respectively) to the open-ended questions “What qualities does an effective triagist have?’ and ‘What qualities make a triagist ineffective?” We identified 22 themes for effective and ineffective qualities, which were grouped into seven domains (Table). All themes had at least three mentions by respondents. The three most frequently mentioned themes, communication skills, efficiency, and systems knowledge, had greater than 60 mentions.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the triagist role at 10 AMCs describes critical triagist functions and identifies key findings across and within AMCs. Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists reported admitting patients even when the patient did not meet the admission criteria, consistent with previous research demonstrating the influence of factors other than clinical disease severity on triage decisions.10 However, preventable admissions remain a hospital-level quality metric.11,12 Triagists must often balance each patient’s circumstances with the complexities of the system. Juggling the competing demands of the system while providing patient-centered care can be challenging and may explain why attending physicians are more frequently filling this role.13

Local context/culture is likely to play a role in the variation across sites; however, compensation for the time spent may also be a factor. If triage activities are not reimbursable, this could lead to less documentation and a lower likelihood that patients are evaluated in person.14 This reason may also explain why all hospitalists were required to serve as a triagist at most sites.

Currently, no consensus definition of the triagist role has been developed. Our results demonstrate that this role is heterogeneous and grounded in the local healthcare system practices. We propose the following working definition of the triagist: a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting. A triagist should be equipped with a skill set that includes not only clinical knowledge but also emphasizes systems knowledge, awareness of others’ goals, efficiency, an ability to communicate effectively, and the knowledge of UM. We recommend that medical directors of hospitalist programs focus their attention on locally specific, systems-based skills development when orienting new hospitalists. The financial aspects of cost should be considered and delineated as well.

Our analysis is limited in several respects. Participant AMCs were not randomly chosen, but do represent a broad array of facility types, group size, and geographic regions. The low response rates at some AMCs may result in an inaccurate representation of those sites. Data was not obtained on hospitalists that did not respond to the survey; therefore, nonresponse bias may affect outcomes. This research used self-report rather than direct observation, which could be subject to recall and social desirability bias. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to nonacademic institutions.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalist role as triagist at AMCs emphasizes communication, organizational skills, efficiency, systems-based practice, and UM knowledge. Although we found significant variation across and within AMCs, internal transfer activities were common across programs. Hospitalist programs should focus on systems-based skills development to prepare hospitalists for the role. The skill set necessary for triagist responsibilities also has implications for internal medicine resident education.4 With increasing emphasis on value and system effectiveness in care delivery, further studies of the triagist role should be undertaken.

Acknowledgments

The TRIAGIST Collaborative Group consists of: Maralyssa Bann, MD, Andrew White, MD (University of Washington); Jagriti Chadha, MD (University of Kentucky); Joel Boggan, MD (Duke University); Sherwin Hsu, MD (UCLA); Jeff Liao, MD (Harvard Medical School); Tabatha Matthias, DO (University of Nebraska Medical Center); Tresa McNeal, MD (Scott and White Texas A&M); Roxana Naderi, MD, Khooshbu Shah, MD (University of Colorado); David Schmit, MD (University of Texas Health San Antonio); Manivannan Veerasamy, MD (Michigan State University).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the po

1. Kisuule F, Howell EE. Hospitalists and their impact on quality, patient safety, and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015; 42(3):433-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2015.05.003.

2. Wachter, RM, Goldman, L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11): 1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

3. Vasilevskis EE, Knebel RJ, Wachter RM, Auerbach AD. California hospital leaders’ views of hospitalists: meeting needs of the present and future. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:528-534. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.529.

4. Wang ES, Velásquez ST, Smith CJ, et al. Triaging inpatient admissions: an opportunity for resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2019; 34(5):754-757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04882-2.

5. Briones A, Markoff B, Kathuria N, et al. A model of a hospitalist role in the care of admitted patients in the emergency department. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):360-364. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.636.

6. Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:266-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30431.x.

7. Howell E, Bessman E, Marshall R, Wright S. Hospitalist bed management effecting throughput from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2010;25:184-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.08.004.

8. Chadaga SR, Shockley L, Keniston A, et al. Hospitalist-led medicine emergency department team: associations with throughput, timeliness of patient care, and satisfaction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:562-566. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1957.

9. Braun, V. Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

10. Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors influencing hospital admission of non-critically ill patients presenting to the emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8.

11. Patel KK, Vakharia N, Pile J, Howell EH, Rothberg MB. Preventable admissions on a general medicine service: prevalence, causes and comparison with AHRQ prevention quality indicators-a cross-sectional analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):597-601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3615-4.

12. Daniels LM1, Sorita A2, Kashiwagi DT, et al. Characterizing potentially preventable admissions: a mixed methods study of rates, associated factors, outcomes, and physician decision-making. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):737-744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4285-6.

13. Howard-Anderson J, Lonowski S, Vangala S, Tseng CH, Busuttil A, Afsar-Manesh N. Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870-1872. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4782.

14. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB, Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1907

1. Kisuule F, Howell EE. Hospitalists and their impact on quality, patient safety, and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015; 42(3):433-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2015.05.003.

2. Wachter, RM, Goldman, L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11): 1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

3. Vasilevskis EE, Knebel RJ, Wachter RM, Auerbach AD. California hospital leaders’ views of hospitalists: meeting needs of the present and future. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:528-534. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.529.

4. Wang ES, Velásquez ST, Smith CJ, et al. Triaging inpatient admissions: an opportunity for resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2019; 34(5):754-757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04882-2.

5. Briones A, Markoff B, Kathuria N, et al. A model of a hospitalist role in the care of admitted patients in the emergency department. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):360-364. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.636.

6. Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:266-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30431.x.

7. Howell E, Bessman E, Marshall R, Wright S. Hospitalist bed management effecting throughput from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2010;25:184-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.08.004.

8. Chadaga SR, Shockley L, Keniston A, et al. Hospitalist-led medicine emergency department team: associations with throughput, timeliness of patient care, and satisfaction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:562-566. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1957.

9. Braun, V. Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

10. Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors influencing hospital admission of non-critically ill patients presenting to the emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8.

11. Patel KK, Vakharia N, Pile J, Howell EH, Rothberg MB. Preventable admissions on a general medicine service: prevalence, causes and comparison with AHRQ prevention quality indicators-a cross-sectional analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):597-601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3615-4.

12. Daniels LM1, Sorita A2, Kashiwagi DT, et al. Characterizing potentially preventable admissions: a mixed methods study of rates, associated factors, outcomes, and physician decision-making. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):737-744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4285-6.

13. Howard-Anderson J, Lonowski S, Vangala S, Tseng CH, Busuttil A, Afsar-Manesh N. Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870-1872. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4782.

14. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB, Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1907

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Delayed ICU Transfer Affects Mortality and Length of Stay

Clinical Question: Can an objective measurement of critical illness inform intensive care unit (ICU) transfer timeliness?

Background: Early intervention has shown mortality benefit in many critical illness syndromes, yet heterogeneity in timing of ICU transfer exists. Previous studies examining ICU transfer timeliness have mostly focused on subjective criteria.

Study Design: Retrospective observational cohort study.

Setting: Medical-surgical units at five hospitals including the University of Chicago and NorthShore University HealthSystem in Illinois.

Synopsis: All medical-surgical ward patients between November 2008 and January 2013 were scored using eCART, a previously validated objective scoring system, to decide when transfer was appropriate. Of those, 3,789 patients reached the predetermined threshold for critical illness. Transfers more than six hours after crossing the threshold were considered delayed. Patients with delayed transfer had a statistically significant increase in length of stay (LOS) and in-hospital mortality (33.2% versus 24.5%; P < 0.001), and the mortality increase was linear, with a 3% increase in odds for each one hour of further transfer delay (P < 0.001). The rate of change of eCART score did influence time of transfer, and the authors suggest that rapid changes were more likely to be recognized. They postulate that routine implementation of eCART or similar objective scoring may lead to earlier recognition of necessary ICU transfer and thus improve mortality and LOS, and they suggest this as a topic for future trials.

Bottom Line: Delayed ICU transfer negatively affects LOS and in-hospital mortality. Objective criteria may identify more appropriate timing of transfer. Clinical trials to investigate this are warranted.

Citation: Churpek MM, Wendlandt B, Zadravecz FJ, Adhikari R, Winslow C, Edelson DP. Association between intensive care unit transfer delay and hospital mortality: a multicenter investigation [published online ahead of print June 28, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2630.

Short Take

Intranasal Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine Not Recommended

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends against use of the nasal spray live attenuated influenza vaccine. This is based on data showing poor effectiveness in prior years.

Citation: ACIP votes down use of LAIV for 2016-2017 flu season [press release]. CDC website.

Clinical Question: Can an objective measurement of critical illness inform intensive care unit (ICU) transfer timeliness?

Background: Early intervention has shown mortality benefit in many critical illness syndromes, yet heterogeneity in timing of ICU transfer exists. Previous studies examining ICU transfer timeliness have mostly focused on subjective criteria.

Study Design: Retrospective observational cohort study.

Setting: Medical-surgical units at five hospitals including the University of Chicago and NorthShore University HealthSystem in Illinois.

Synopsis: All medical-surgical ward patients between November 2008 and January 2013 were scored using eCART, a previously validated objective scoring system, to decide when transfer was appropriate. Of those, 3,789 patients reached the predetermined threshold for critical illness. Transfers more than six hours after crossing the threshold were considered delayed. Patients with delayed transfer had a statistically significant increase in length of stay (LOS) and in-hospital mortality (33.2% versus 24.5%; P < 0.001), and the mortality increase was linear, with a 3% increase in odds for each one hour of further transfer delay (P < 0.001). The rate of change of eCART score did influence time of transfer, and the authors suggest that rapid changes were more likely to be recognized. They postulate that routine implementation of eCART or similar objective scoring may lead to earlier recognition of necessary ICU transfer and thus improve mortality and LOS, and they suggest this as a topic for future trials.

Bottom Line: Delayed ICU transfer negatively affects LOS and in-hospital mortality. Objective criteria may identify more appropriate timing of transfer. Clinical trials to investigate this are warranted.

Citation: Churpek MM, Wendlandt B, Zadravecz FJ, Adhikari R, Winslow C, Edelson DP. Association between intensive care unit transfer delay and hospital mortality: a multicenter investigation [published online ahead of print June 28, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2630.

Short Take

Intranasal Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine Not Recommended

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends against use of the nasal spray live attenuated influenza vaccine. This is based on data showing poor effectiveness in prior years.

Citation: ACIP votes down use of LAIV for 2016-2017 flu season [press release]. CDC website.

Clinical Question: Can an objective measurement of critical illness inform intensive care unit (ICU) transfer timeliness?

Background: Early intervention has shown mortality benefit in many critical illness syndromes, yet heterogeneity in timing of ICU transfer exists. Previous studies examining ICU transfer timeliness have mostly focused on subjective criteria.

Study Design: Retrospective observational cohort study.

Setting: Medical-surgical units at five hospitals including the University of Chicago and NorthShore University HealthSystem in Illinois.

Synopsis: All medical-surgical ward patients between November 2008 and January 2013 were scored using eCART, a previously validated objective scoring system, to decide when transfer was appropriate. Of those, 3,789 patients reached the predetermined threshold for critical illness. Transfers more than six hours after crossing the threshold were considered delayed. Patients with delayed transfer had a statistically significant increase in length of stay (LOS) and in-hospital mortality (33.2% versus 24.5%; P < 0.001), and the mortality increase was linear, with a 3% increase in odds for each one hour of further transfer delay (P < 0.001). The rate of change of eCART score did influence time of transfer, and the authors suggest that rapid changes were more likely to be recognized. They postulate that routine implementation of eCART or similar objective scoring may lead to earlier recognition of necessary ICU transfer and thus improve mortality and LOS, and they suggest this as a topic for future trials.

Bottom Line: Delayed ICU transfer negatively affects LOS and in-hospital mortality. Objective criteria may identify more appropriate timing of transfer. Clinical trials to investigate this are warranted.

Citation: Churpek MM, Wendlandt B, Zadravecz FJ, Adhikari R, Winslow C, Edelson DP. Association between intensive care unit transfer delay and hospital mortality: a multicenter investigation [published online ahead of print June 28, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2630.

Short Take

Intranasal Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine Not Recommended

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends against use of the nasal spray live attenuated influenza vaccine. This is based on data showing poor effectiveness in prior years.

Citation: ACIP votes down use of LAIV for 2016-2017 flu season [press release]. CDC website.

IV Fluid Can Save Lives in Hemodynamically Stable Patients with Sepsis

Clinical Question: Does increased fluid administration in patients with sepsis with intermediate lactate levels improve outcomes?

Background: The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle, which improves ED mortality, targets patients with hypotension or lactate levels >4 mmol/L. No similar optimal treatment strategy exists for less severe sepsis patients even though such patients are more common in hospitalized populations.

Study Design: Retrospective study of a quality improvement bundle.

Setting: 21 community-based hospitals in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California system.

Synopsis: This study evaluated implementation of a treatment bundle for 18,122 hemodynamically stable sepsis patients presenting to the ED with lactate levels between 2 and 4 mmol/L during the 12 months prior to and after bundle implementation. The bundle included antibiotic administration within three hours, repeated lactate levels within four hours, and 30 mL/kg or ≥2 L of intravenous fluids within three hours of initial lactate result. Patients with kidney disease and/or heart failure were separately evaluated because of the perceived risk of fluid administration.

Treatment after bundle implementation was associated with an adjusted hospital mortality odds ratio of 0.81 (95% CI, 0.66–0.99; P = 0.04). Significant reductions in hospital mortality were observed in patients with heart failure and/or kidney disease (P < 0.01) but not without (P > 0.4). This correlated with increased fluid administration in patients with heart failure and/or kidney disease following bundle implementation. This is not a randomized controlled study, which invites biases and confounding.

Bottom Line: Increased fluid administration improved mortality in patients with kidney disease and heart failure presenting with sepsis.

Reference: Liu V, Morehouse JW, Marelich GP, et al. Multicenter implementation of a treatment bundle for patients with sepsis and intermediate lactate values. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(11):1264-1270.

Short Take

New Framework for Learners’ Clinical Reasoning

A qualitative study involving 37 emergency medicine residents found that clinical reasoning through individual cases progresses from case framing (phase 1) to pattern recognition (phase 2), then self-monitoring (phase 3).

Citation: Adams E, Goyder C, Heneghan C, Brand L, Ajjawi R. Clinical reasoning of junior doctors in emergency medicine: a grounded theory study [published online ahead of print June 23, 2016]. Emerg Med J. doi:10.1136/emermed-2015-205650.

Clinical Question: Does increased fluid administration in patients with sepsis with intermediate lactate levels improve outcomes?

Background: The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle, which improves ED mortality, targets patients with hypotension or lactate levels >4 mmol/L. No similar optimal treatment strategy exists for less severe sepsis patients even though such patients are more common in hospitalized populations.

Study Design: Retrospective study of a quality improvement bundle.

Setting: 21 community-based hospitals in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California system.

Synopsis: This study evaluated implementation of a treatment bundle for 18,122 hemodynamically stable sepsis patients presenting to the ED with lactate levels between 2 and 4 mmol/L during the 12 months prior to and after bundle implementation. The bundle included antibiotic administration within three hours, repeated lactate levels within four hours, and 30 mL/kg or ≥2 L of intravenous fluids within three hours of initial lactate result. Patients with kidney disease and/or heart failure were separately evaluated because of the perceived risk of fluid administration.

Treatment after bundle implementation was associated with an adjusted hospital mortality odds ratio of 0.81 (95% CI, 0.66–0.99; P = 0.04). Significant reductions in hospital mortality were observed in patients with heart failure and/or kidney disease (P < 0.01) but not without (P > 0.4). This correlated with increased fluid administration in patients with heart failure and/or kidney disease following bundle implementation. This is not a randomized controlled study, which invites biases and confounding.

Bottom Line: Increased fluid administration improved mortality in patients with kidney disease and heart failure presenting with sepsis.

Reference: Liu V, Morehouse JW, Marelich GP, et al. Multicenter implementation of a treatment bundle for patients with sepsis and intermediate lactate values. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(11):1264-1270.

Short Take

New Framework for Learners’ Clinical Reasoning

A qualitative study involving 37 emergency medicine residents found that clinical reasoning through individual cases progresses from case framing (phase 1) to pattern recognition (phase 2), then self-monitoring (phase 3).

Citation: Adams E, Goyder C, Heneghan C, Brand L, Ajjawi R. Clinical reasoning of junior doctors in emergency medicine: a grounded theory study [published online ahead of print June 23, 2016]. Emerg Med J. doi:10.1136/emermed-2015-205650.

Clinical Question: Does increased fluid administration in patients with sepsis with intermediate lactate levels improve outcomes?

Background: The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle, which improves ED mortality, targets patients with hypotension or lactate levels >4 mmol/L. No similar optimal treatment strategy exists for less severe sepsis patients even though such patients are more common in hospitalized populations.

Study Design: Retrospective study of a quality improvement bundle.

Setting: 21 community-based hospitals in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California system.

Synopsis: This study evaluated implementation of a treatment bundle for 18,122 hemodynamically stable sepsis patients presenting to the ED with lactate levels between 2 and 4 mmol/L during the 12 months prior to and after bundle implementation. The bundle included antibiotic administration within three hours, repeated lactate levels within four hours, and 30 mL/kg or ≥2 L of intravenous fluids within three hours of initial lactate result. Patients with kidney disease and/or heart failure were separately evaluated because of the perceived risk of fluid administration.

Treatment after bundle implementation was associated with an adjusted hospital mortality odds ratio of 0.81 (95% CI, 0.66–0.99; P = 0.04). Significant reductions in hospital mortality were observed in patients with heart failure and/or kidney disease (P < 0.01) but not without (P > 0.4). This correlated with increased fluid administration in patients with heart failure and/or kidney disease following bundle implementation. This is not a randomized controlled study, which invites biases and confounding.

Bottom Line: Increased fluid administration improved mortality in patients with kidney disease and heart failure presenting with sepsis.

Reference: Liu V, Morehouse JW, Marelich GP, et al. Multicenter implementation of a treatment bundle for patients with sepsis and intermediate lactate values. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(11):1264-1270.

Short Take

New Framework for Learners’ Clinical Reasoning

A qualitative study involving 37 emergency medicine residents found that clinical reasoning through individual cases progresses from case framing (phase 1) to pattern recognition (phase 2), then self-monitoring (phase 3).

Citation: Adams E, Goyder C, Heneghan C, Brand L, Ajjawi R. Clinical reasoning of junior doctors in emergency medicine: a grounded theory study [published online ahead of print June 23, 2016]. Emerg Med J. doi:10.1136/emermed-2015-205650.

Real-World Safety and Effectiveness of Oral Anticoagulants for Afib

Clinical Question: Which oral anticoagulants are safest and most effective in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation?

Background: Use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) has been increasing since their introduction and widespread marketing. While dosing is a challenge for warfarin, certain medical conditions limit the use of DOACs. Choosing the optimal oral anticoagulant is challenging with the increasing complexity of patients.

Study Design: Nationwide observational cohort study.

Setting: Three national Danish databases, from August 2011 to October 2015.

Synopsis: Authors reviewed data from 61,678 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who were new to oral anticoagulants. The study compared the efficacy, safety, and patient characteristics of DOACs and warfarin. Ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, and death were evaluated separately and as a composite measure of efficacy. Any bleeding, intracranial bleeding, and major bleeding were measured as safety outcomes. DOACs patients were younger and had lower CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores. No significant difference in risk of ischemic stroke was identified between DOACs and warfarin. Rivaroxaban was associated with lower rates of ischemic stroke and systemic embolism but had bleeding rates that were similar to warfarin. Any bleeding and major bleeding rates were lowest for dabigatran and apixaban. All-cause mortality was lowest in the dabigatran group and highest in the warfarin group.

Limitations were the retrospective, observational study design, with an average follow-up of only 1.9 years.

Bottom Line: All DOACs appear to be safer and more effective alternatives to warfarin. Oral anticoagulant selection needs to be based on individual patient clinical profile.

Citation: Larsen TB, Skjoth F, Nielsen PB, Kjaeldgaard JN, Lip GY. Comparative effectiveness and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: propensity weighted nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i3189.

Short Take

Mortality and Long-Acting Opiates

This retrospective cohort study raises questions about the safety of long-acting opioids for chronic noncancer pain. When compared with anticonvulsants or antidepressants, the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.64 for total mortality.

Citation: Ray W, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2423.

Clinical Question: Which oral anticoagulants are safest and most effective in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation?

Background: Use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) has been increasing since their introduction and widespread marketing. While dosing is a challenge for warfarin, certain medical conditions limit the use of DOACs. Choosing the optimal oral anticoagulant is challenging with the increasing complexity of patients.

Study Design: Nationwide observational cohort study.

Setting: Three national Danish databases, from August 2011 to October 2015.

Synopsis: Authors reviewed data from 61,678 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who were new to oral anticoagulants. The study compared the efficacy, safety, and patient characteristics of DOACs and warfarin. Ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, and death were evaluated separately and as a composite measure of efficacy. Any bleeding, intracranial bleeding, and major bleeding were measured as safety outcomes. DOACs patients were younger and had lower CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores. No significant difference in risk of ischemic stroke was identified between DOACs and warfarin. Rivaroxaban was associated with lower rates of ischemic stroke and systemic embolism but had bleeding rates that were similar to warfarin. Any bleeding and major bleeding rates were lowest for dabigatran and apixaban. All-cause mortality was lowest in the dabigatran group and highest in the warfarin group.

Limitations were the retrospective, observational study design, with an average follow-up of only 1.9 years.

Bottom Line: All DOACs appear to be safer and more effective alternatives to warfarin. Oral anticoagulant selection needs to be based on individual patient clinical profile.

Citation: Larsen TB, Skjoth F, Nielsen PB, Kjaeldgaard JN, Lip GY. Comparative effectiveness and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: propensity weighted nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i3189.

Short Take

Mortality and Long-Acting Opiates

This retrospective cohort study raises questions about the safety of long-acting opioids for chronic noncancer pain. When compared with anticonvulsants or antidepressants, the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.64 for total mortality.

Citation: Ray W, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2423.

Clinical Question: Which oral anticoagulants are safest and most effective in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation?

Background: Use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) has been increasing since their introduction and widespread marketing. While dosing is a challenge for warfarin, certain medical conditions limit the use of DOACs. Choosing the optimal oral anticoagulant is challenging with the increasing complexity of patients.

Study Design: Nationwide observational cohort study.

Setting: Three national Danish databases, from August 2011 to October 2015.

Synopsis: Authors reviewed data from 61,678 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who were new to oral anticoagulants. The study compared the efficacy, safety, and patient characteristics of DOACs and warfarin. Ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, and death were evaluated separately and as a composite measure of efficacy. Any bleeding, intracranial bleeding, and major bleeding were measured as safety outcomes. DOACs patients were younger and had lower CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores. No significant difference in risk of ischemic stroke was identified between DOACs and warfarin. Rivaroxaban was associated with lower rates of ischemic stroke and systemic embolism but had bleeding rates that were similar to warfarin. Any bleeding and major bleeding rates were lowest for dabigatran and apixaban. All-cause mortality was lowest in the dabigatran group and highest in the warfarin group.

Limitations were the retrospective, observational study design, with an average follow-up of only 1.9 years.

Bottom Line: All DOACs appear to be safer and more effective alternatives to warfarin. Oral anticoagulant selection needs to be based on individual patient clinical profile.

Citation: Larsen TB, Skjoth F, Nielsen PB, Kjaeldgaard JN, Lip GY. Comparative effectiveness and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: propensity weighted nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i3189.

Short Take

Mortality and Long-Acting Opiates

This retrospective cohort study raises questions about the safety of long-acting opioids for chronic noncancer pain. When compared with anticonvulsants or antidepressants, the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.64 for total mortality.

Citation: Ray W, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2423.

Prescribing Naloxone for Patients on Long-Term Opioid Therapy

Background: Unintentional opioid overdose is a major public health issue. Studies have shown that provision of naloxone to at-risk patients reduces mortality and improves survival. The CDC recommends considering naloxone prescription in high-risk patients. This study focused on patient education and prescription habits of providers rather than just making naloxone available.

Study Design: Non-randomized interventional study.

Setting: Six safety-net primary-care clinics in San Francisco.

Synopsis: The authors identified 1,985 adults on long-term opioid treatment, of which 759 were prescribed naloxone. Providers were encouraged to prescribe naloxone along with opioids. Patients were educated about use of the intranasal naloxone device. Outcomes included opioid-related emergency department visits and prescribed dosage. They noted that patients on a higher dose of opioids and with opioid-related ED visits in the prior 12 months were more likely to be prescribed naloxone. When compared to patients who were not prescribed naloxone, patients who received naloxone had 47% fewer ED visits per month in the first six months and 63% fewer ED visits over 12 months. Limitations include lack of randomization and being a single-center study.

Hospitalists can prioritize patients and consider providing naloxone prescription to reduce ED visits and perhaps readmissions. Further studies are needed focusing on patients who get discharged from the hospital.

Bottom Line: Naloxone prescription in patients on long-term opioid treatment may prevent opioid-related ED visits.

Citation: Coffin PO, Behar E, Rowe C, et al. Nonrandomized intervention study of naloxone coprescription for primary care patients receiving long-term opioid therapy for pain. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(4):245-252.

Short Take

Mortality and Long-Acting Opiates

This retrospective cohort study raises questions about the safety of long-acting opioids for chronic noncancer pain. When compared with anticonvulsants or antidepressants, the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.64 for total mortality.

Citation: Ray W, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2423.

Background: Unintentional opioid overdose is a major public health issue. Studies have shown that provision of naloxone to at-risk patients reduces mortality and improves survival. The CDC recommends considering naloxone prescription in high-risk patients. This study focused on patient education and prescription habits of providers rather than just making naloxone available.

Study Design: Non-randomized interventional study.

Setting: Six safety-net primary-care clinics in San Francisco.

Synopsis: The authors identified 1,985 adults on long-term opioid treatment, of which 759 were prescribed naloxone. Providers were encouraged to prescribe naloxone along with opioids. Patients were educated about use of the intranasal naloxone device. Outcomes included opioid-related emergency department visits and prescribed dosage. They noted that patients on a higher dose of opioids and with opioid-related ED visits in the prior 12 months were more likely to be prescribed naloxone. When compared to patients who were not prescribed naloxone, patients who received naloxone had 47% fewer ED visits per month in the first six months and 63% fewer ED visits over 12 months. Limitations include lack of randomization and being a single-center study.

Hospitalists can prioritize patients and consider providing naloxone prescription to reduce ED visits and perhaps readmissions. Further studies are needed focusing on patients who get discharged from the hospital.

Bottom Line: Naloxone prescription in patients on long-term opioid treatment may prevent opioid-related ED visits.

Citation: Coffin PO, Behar E, Rowe C, et al. Nonrandomized intervention study of naloxone coprescription for primary care patients receiving long-term opioid therapy for pain. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(4):245-252.

Short Take

Mortality and Long-Acting Opiates

This retrospective cohort study raises questions about the safety of long-acting opioids for chronic noncancer pain. When compared with anticonvulsants or antidepressants, the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.64 for total mortality.

Citation: Ray W, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2423.

Background: Unintentional opioid overdose is a major public health issue. Studies have shown that provision of naloxone to at-risk patients reduces mortality and improves survival. The CDC recommends considering naloxone prescription in high-risk patients. This study focused on patient education and prescription habits of providers rather than just making naloxone available.

Study Design: Non-randomized interventional study.

Setting: Six safety-net primary-care clinics in San Francisco.

Synopsis: The authors identified 1,985 adults on long-term opioid treatment, of which 759 were prescribed naloxone. Providers were encouraged to prescribe naloxone along with opioids. Patients were educated about use of the intranasal naloxone device. Outcomes included opioid-related emergency department visits and prescribed dosage. They noted that patients on a higher dose of opioids and with opioid-related ED visits in the prior 12 months were more likely to be prescribed naloxone. When compared to patients who were not prescribed naloxone, patients who received naloxone had 47% fewer ED visits per month in the first six months and 63% fewer ED visits over 12 months. Limitations include lack of randomization and being a single-center study.

Hospitalists can prioritize patients and consider providing naloxone prescription to reduce ED visits and perhaps readmissions. Further studies are needed focusing on patients who get discharged from the hospital.

Bottom Line: Naloxone prescription in patients on long-term opioid treatment may prevent opioid-related ED visits.

Citation: Coffin PO, Behar E, Rowe C, et al. Nonrandomized intervention study of naloxone coprescription for primary care patients receiving long-term opioid therapy for pain. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(4):245-252.

Short Take

Mortality and Long-Acting Opiates

This retrospective cohort study raises questions about the safety of long-acting opioids for chronic noncancer pain. When compared with anticonvulsants or antidepressants, the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.64 for total mortality.

Citation: Ray W, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2423.

Palliative Care May Improve End-of-Life Care for Patients with ESRD, Cardiopulmonary Failure, Frailty

Clinical Question: Is there a difference in family-rated quality of care for patients dying with different serious illnesses?

Background: End-of-life care has focused largely on cancer patients. However, other conditions lead to more deaths than cancer in the United States.

Study Design: A retrospective cross-sectional study.

Setting: 146 inpatient Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities.

Synopsis: This study included 57,753 patients who died in inpatient facilities with a diagnosis of cancer, dementia, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), cardiopulmonary failure (heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), or frailty. Measures included palliative care consultations, do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, death in inpatient hospice, death in the intensive care unit (ICU), and family-reported quality of end-of-life care. Palliative care consultations were given to 73.5% of patients with cancer and 61.4% of patients with dementia, which was significantly more than patients with other diagnoses (P < .001).

Approximately one-third of patients with diagnoses other than cancer or dementia died in the ICU, which was more than double the rate among patients with cancer or dementia (P < .001). Rates of excellent quality of end-of-life care were similar for patients with cancer and dementia (59.2% and 59.3%) but lower for other conditions (P = 0.02 when compared with cancer patient). This was mediated by palliative care consultation, setting of death, and DNR status. Difficulty defining frailty and restriction to only the VA system are limitations of this study.

Bottom Line: Increasing access to palliative care, goals-of-care discussions, and preferred setting of death may improve overall quality of end-of-life care.

Citation: Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1095-1102. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1200.

Clinical Question: Is there a difference in family-rated quality of care for patients dying with different serious illnesses?

Background: End-of-life care has focused largely on cancer patients. However, other conditions lead to more deaths than cancer in the United States.

Study Design: A retrospective cross-sectional study.

Setting: 146 inpatient Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities.

Synopsis: This study included 57,753 patients who died in inpatient facilities with a diagnosis of cancer, dementia, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), cardiopulmonary failure (heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), or frailty. Measures included palliative care consultations, do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, death in inpatient hospice, death in the intensive care unit (ICU), and family-reported quality of end-of-life care. Palliative care consultations were given to 73.5% of patients with cancer and 61.4% of patients with dementia, which was significantly more than patients with other diagnoses (P < .001).

Approximately one-third of patients with diagnoses other than cancer or dementia died in the ICU, which was more than double the rate among patients with cancer or dementia (P < .001). Rates of excellent quality of end-of-life care were similar for patients with cancer and dementia (59.2% and 59.3%) but lower for other conditions (P = 0.02 when compared with cancer patient). This was mediated by palliative care consultation, setting of death, and DNR status. Difficulty defining frailty and restriction to only the VA system are limitations of this study.

Bottom Line: Increasing access to palliative care, goals-of-care discussions, and preferred setting of death may improve overall quality of end-of-life care.

Citation: Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1095-1102. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1200.

Clinical Question: Is there a difference in family-rated quality of care for patients dying with different serious illnesses?

Background: End-of-life care has focused largely on cancer patients. However, other conditions lead to more deaths than cancer in the United States.

Study Design: A retrospective cross-sectional study.

Setting: 146 inpatient Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities.

Synopsis: This study included 57,753 patients who died in inpatient facilities with a diagnosis of cancer, dementia, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), cardiopulmonary failure (heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), or frailty. Measures included palliative care consultations, do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, death in inpatient hospice, death in the intensive care unit (ICU), and family-reported quality of end-of-life care. Palliative care consultations were given to 73.5% of patients with cancer and 61.4% of patients with dementia, which was significantly more than patients with other diagnoses (P < .001).