User login

Review of Physiologic Monitor Alarms

Clinical alarm safety has become a recent target for improvement in many hospitals. In 2013, The Joint Commission released a National Patient Safety Goal prompting accredited hospitals to establish alarm safety as a hospital priority, identify the most important alarm signals to manage, and, by 2016, develop policies and procedures that address alarm management.[1] In addition, the Emergency Care Research Institute has named alarm hazards the top health technology hazard each year since 2012.[2]

The primary arguments supporting the elevation of alarm management to a national hospital priority in the United States include the following: (1) clinicians rely on alarms to notify them of important physiologic changes, (2) alarms occur frequently and usually do not warrant clinical intervention, and (3) alarm overload renders clinicians unable to respond to all alarms, resulting in alarm fatigue: responding more slowly or ignoring alarms that may represent actual clinical deterioration.[3, 4] These arguments are built largely on anecdotal data, reported safety event databases, and small studies that have not previously been systematically analyzed.

Despite the national focus on alarms, we still know very little about fundamental questions key to improving alarm safety. In this systematic review, we aimed to answer 3 key questions about physiologic monitor alarms: (1) What proportion of alarms warrant attention or clinical intervention (ie, actionable alarms), and how does this proportion vary between adult and pediatric populations and between intensive care unit (ICU) and ward settings? (2) What is the relationship between alarm exposure and clinician response time? (3) What interventions are effective in reducing the frequency of alarms?

We limited our scope to monitor alarms because few studies have evaluated the characteristics of alarms from other medical devices, and because missing relevant monitor alarms could adversely impact patient safety.

METHODS

We performed a systematic review of the literature in accordance with the Meta‐Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines[5] and developed this manuscript using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement.[6]

Eligibility Criteria

With help from an experienced biomedical librarian (C.D.S.), we searched PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Scopus, Cochrane Library,

We included peer‐reviewed, original research studies published in English, Spanish, or French that addressed the questions outlined above. Eligible patient populations were children and adults admitted to hospital inpatient units and emergency departments (EDs). We excluded alarms in procedural suites or operating rooms (typically responded to by anesthesiologists already with the patient) because of the differences in environment of care, staff‐to‐patient ratio, and equipment. We included observational studies reporting the actionability of physiologic monitor alarms (ie, alarms warranting special attention or clinical intervention), as well as nurse responses to these alarms. We excluded studies focused on the effects of alarms unrelated to patient safety, such as families' and patients' stress, noise, or sleep disturbance. We included only intervention studies evaluating pragmatic interventions ready for clinical implementation (ie, not experimental devices or software algorithms).

Selection Process and Data Extraction

First, 2 authors screened the titles and abstracts of articles for eligibility. To maximize sensitivity, if at least 1 author considered the article relevant, the article proceeded to full‐text review. Second, the full texts of articles screened were independently reviewed by 2 authors in an unblinded fashion to determine their eligibility. Any disagreements concerning eligibility were resolved by team consensus. To assure consistency in eligibility determinations across the team, a core group of the authors (C.W.P, C.P.B., E.E., and V.V.G.) held a series of meetings to review and discuss each potentially eligible article and reach consensus on the final list of included articles. Two authors independently extracted the following characteristics from included studies: alarm review methods, analytic design, fidelity measurement, consideration of unintended adverse safety consequences, and key results. Reviewers were not blinded to journal, authors, or affiliations.

Synthesis of Results and Risk Assessment

Given the high degree of heterogeneity in methodology, we were unable to generate summary proportions of the observational studies or perform a meta‐analysis of the intervention studies. Thus, we organized the studies into clinically relevant categories and presented key aspects in tables. Due to the heterogeneity of the studies and the controversy surrounding quality scores,[5] we did not generate summary scores of study quality. Instead, we evaluated and reported key design elements that had the potential to bias the results. To recognize the more comprehensive studies in the field, we developed by consensus a set of characteristics that distinguished studies with lower risk of bias. These characteristics are shown and defined in Table 1.

| First Author and Publication Year | Alarm Review Method | Indicators of Potential Bias for Observational Studies | Indicators of Potential Bias for Intervention Studies | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitor System | Direct Observation | Medical Record Review | Rhythm Annotation | Video Observation | Remote Monitoring Staff | Medical Device Industry Involved | Two Independent Reviewers | At Least 1 Reviewer Is a Clinical Expert | Reviewer Not Simultaneously in Patient Care | Clear Definition of Alarm Actionability | Census Included | Statistical Testing or QI SPC Methods | Fidelity Assessed | Safety Assessed | Lower Risk of Bias | |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Adult Observational | ||||||||||||||||

| Atzema 2006[7] | ✓* | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Billinghurst 2003[8] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Biot 2000[9] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Chambrin 1999[10] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Drew 2014[11] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gazarian 2014[12] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Grges 2009[13] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Gross 2011[15] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Inokuchi 2013[14] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Koski 1990[16] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Morales Snchez 2014[17] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Pergher 2014[18] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Siebig 2010[19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Voepel‐Lewis 2013[20] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Way 2014[21] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Pediatric Observational | ||||||||||||||||

| Bonafide 2015[22] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lawless 1994[23] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Rosman 2013[24] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Talley 2011[25] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Tsien 1997[26] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| van Pul 2015[27] | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Varpio 2012[28] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mixed Adult and Pediatric Observational | ||||||||||||||||

| O'Carroll 1986[29] | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Wiklund 1994[30] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Adult Intervention | ||||||||||||||||

| Albert 2015[32] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cvach 2013[33] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Cvach 2014[34] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Graham 2010[35] | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Rheineck‐Leyssius 1997[36] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Taenzer 2010[31] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Whalen 2014[37] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Pediatric Intervention | ||||||||||||||||

| Dandoy 2014[38] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

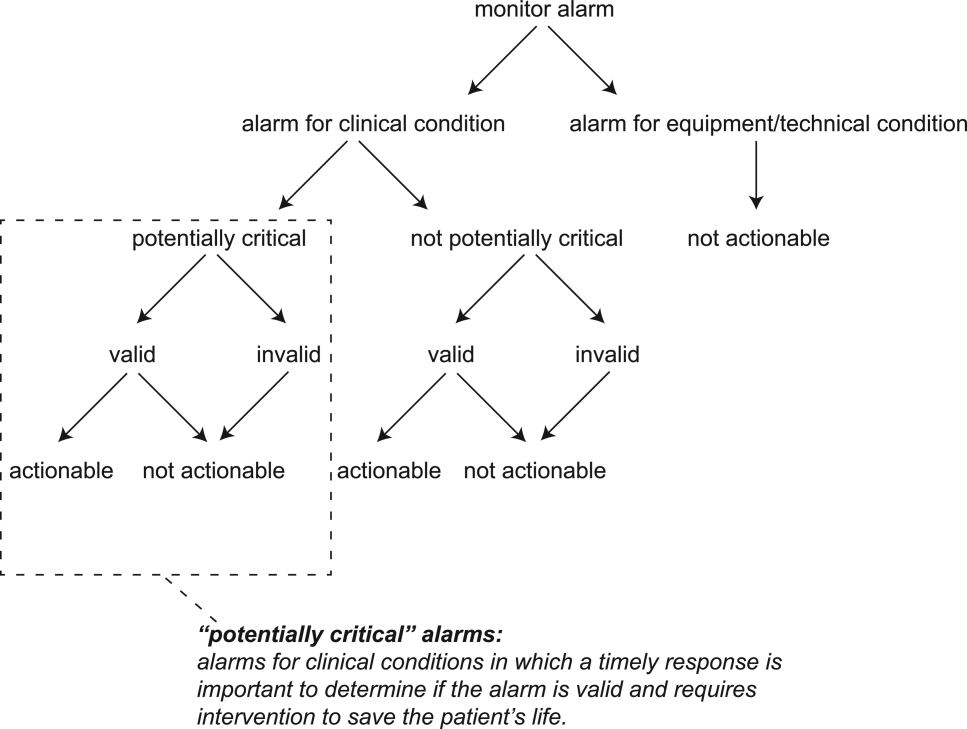

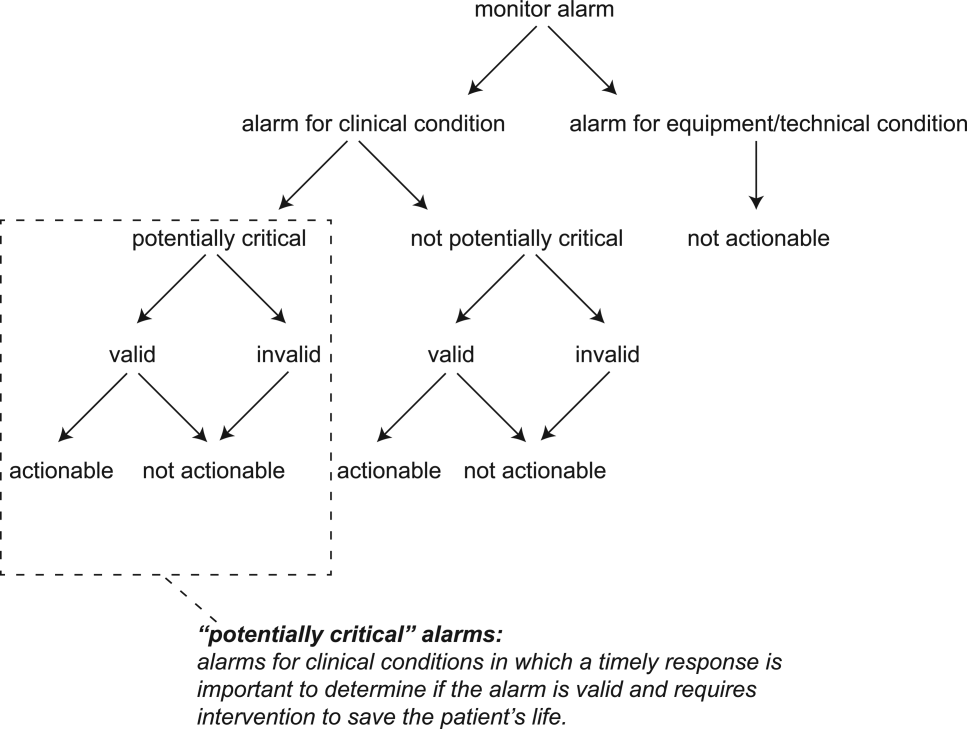

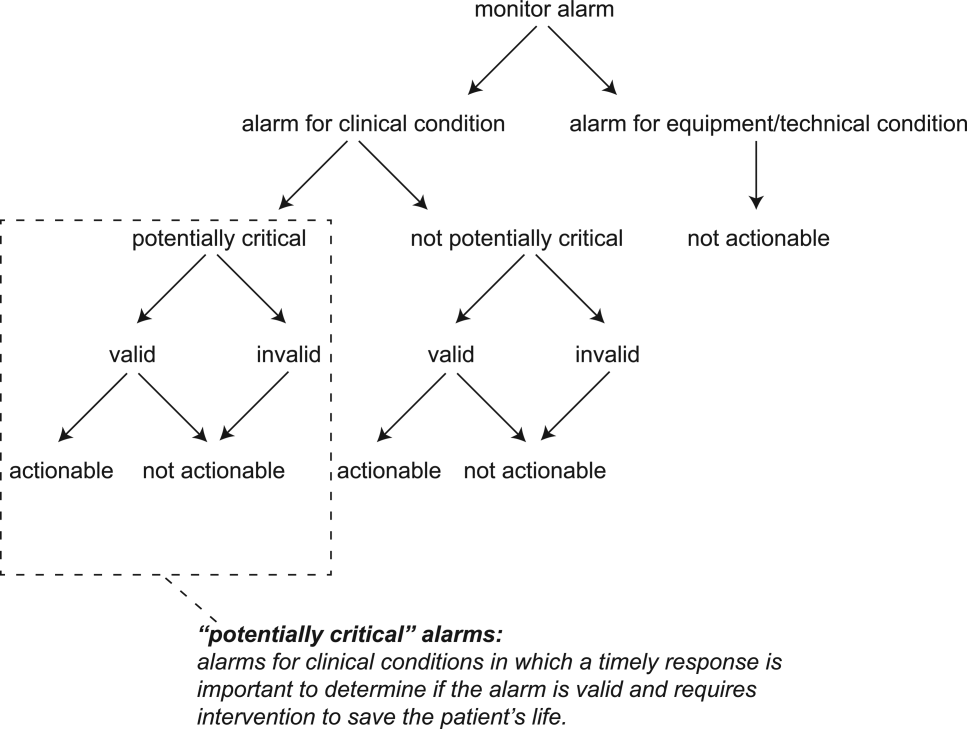

For the purposes of this review, we defined nonactionable alarms as including both invalid (false) alarms that do not that accurately represent the physiologic status of the patient and alarms that are valid but do not warrant special attention or clinical intervention (nuisance alarms). We did not separate out invalid alarms due to the tremendous variation between studies in how validity was measured.

RESULTS

Study Selection

Search results produced 4629 articles (see the flow diagram in the Supporting Information in the online version of this article), of which 32 articles were eligible: 24 observational studies describing alarm characteristics and 8 studies describing interventions to reduce alarm frequency.

Observational Study Characteristics

Characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 1. Of the 24 observational studies,[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] 15 included adult patients,[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21] 7 included pediatric patients,[22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28] and 2 included both adult and pediatric patients.[29, 30] All were single‐hospital studies, except for 1 study by Chambrin and colleagues[10] that included 5 sites. The number of patient‐hours examined in each study ranged from 60 to 113,880.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30] Hospital settings included ICUs (n = 16),[9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29] general wards (n = 5),[12, 15, 20, 22, 28] EDs (n = 2),[7, 21] postanesthesia care unit (PACU) (n = 1),[30] and cardiac care unit (CCU) (n = 1).[8] Studies varied in the type of physiologic signals recorded and data collection methods, ranging from direct observation by a nurse who was simultaneously caring for patients[29] to video recording with expert review.[14, 19, 22] Four observational studies met the criteria for lower risk of bias.[11, 14, 15, 22]

Intervention Study Characteristics

Of the 8 intervention studies, 7 included adult patients,[31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37] and 1 included pediatric patients.[38] All were single‐hospital studies; 6 were quasi‐experimental[31, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38] and 2 were experimental.[32, 36] Settings included progressive care units (n = 3),[33, 34, 35] CCUs (n = 3),[32, 33, 37] wards (n = 2),[31, 38] PACU (n = 1),[36] and a step‐down unit (n = 1).[32] All except 1 study[32] used the monitoring system to record alarm data. Several studies evaluated multicomponent interventions that included combinations of the following: widening alarm parameters,[31, 35, 36, 37, 38] instituting alarm delays,[31, 34, 36, 38] reconfiguring alarm acuity,[35, 37] use of secondary notifications,[34] daily change of electrocardiographic electrodes or use of disposable electrocardiographic wires,[32, 33, 38] universal monitoring in high‐risk populations,[31] and timely discontinuation of monitoring in low‐risk populations.[38] Four intervention studies met our prespecified lower risk of bias criteria.[31, 32, 36, 38]

Proportion of Alarms Considered Actionable

Results of the observational studies are provided in Table 2. The proportion of alarms that were actionable was <1% to 26% in adult ICU settings,[9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 19] 20% to 36% in adult ward settings,[12, 15, 20] 17% in a mixed adult and pediatric PACU setting,[30] 3% to 13% in pediatric ICU settings,[22, 23, 24, 25, 26] and 1% in a pediatric ward setting.[22]

| Signals Included | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Author and Publication Year | Setting | Monitored Patient‐Hours | SpO2 | ECG Arrhythmia | ECG Parametersa | Blood Pressure | Total Alarms | Actionable Alarms | Alarm Response | Lower Risk of Bias |

| ||||||||||

| Adult | ||||||||||

| Atzema 2006[7] | ED | 371 | ✓ | 1,762 | 0.20% | |||||

| Billinghurst 2003[8] | CCU | 420 | ✓ | 751 | Not reported; 17% were valid | Nurses with higher acuity patients and smaller % of valid alarms had slower response rates | ||||

| Biot 2000[9] | ICU | 250 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3,665 | 3% | ||

| Chambrin 1999[10] | ICU | 1,971 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3,188 | 26% | ||

| Drew 2014[11] | ICU | 48,173 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,558,760 | 0.3% of 3,861 VT alarms | ✓ | |

| Gazarian 2014[12] | Ward | 54 nurse‐hours | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 205 | 22% | Response to 47% of alarms | ||

| Grges 2009[13] | ICU | 200 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1,214 | 5% | ||

| Gross 2011[15] | Ward | 530 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4,393 | 20% | ✓ | |

| Inokuchi 2013[14] | ICU | 2,697 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 11,591 | 6% | ✓ | |

| Koski 1990[16] | ICU | 400 | ✓ | ✓ | 2,322 | 12% | ||||

| Morales Snchez 2014[17] | ICU | 434 sessions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 215 | 25% | Response to 93% of alarms, of which 50% were within 10 seconds | ||

| Pergher 2014[18] | ICU | 60 | ✓ | 76 | Not reported | 72% of alarms stopped before nurse response or had >10 minutes response time | ||||

| Siebig 2010[19] | ICU | 982 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5,934 | 15% | ||

| Voepel‐Lewis 2013[20] | Ward | 1,616 | ✓ | 710 | 36% | Response time was longer for patients in highest quartile of total alarms | ||||

| Way 2014[21] | ED | 93 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 572 | Not reported; 75% were valid | Nurses responded to more alarms in resuscitation room vs acute care area, but response time was longer | |

| Pediatric | ||||||||||

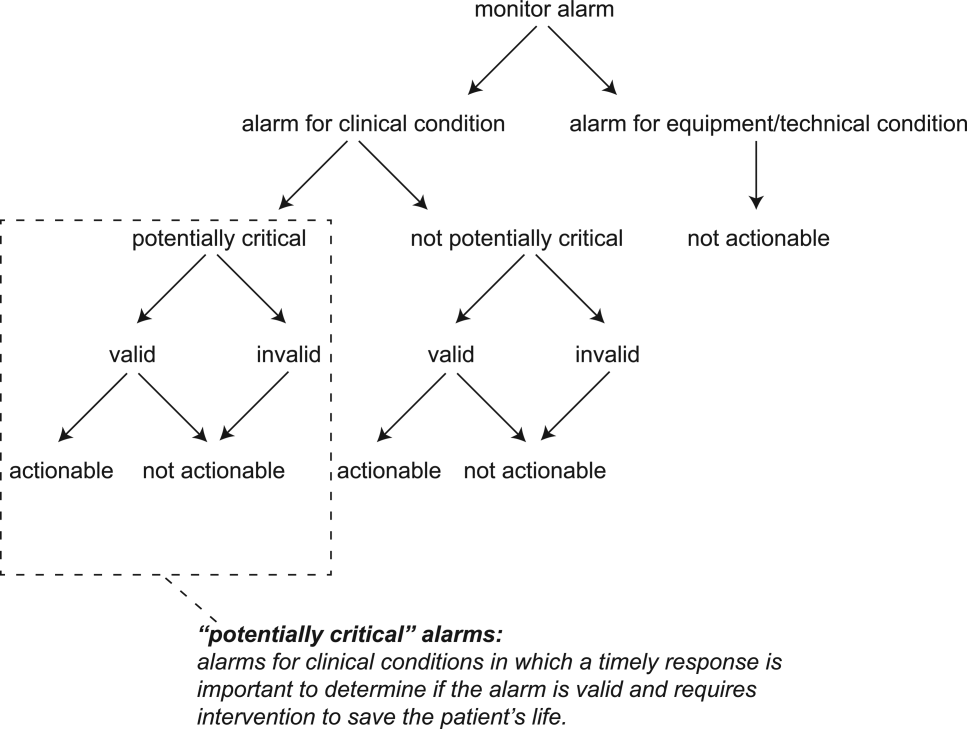

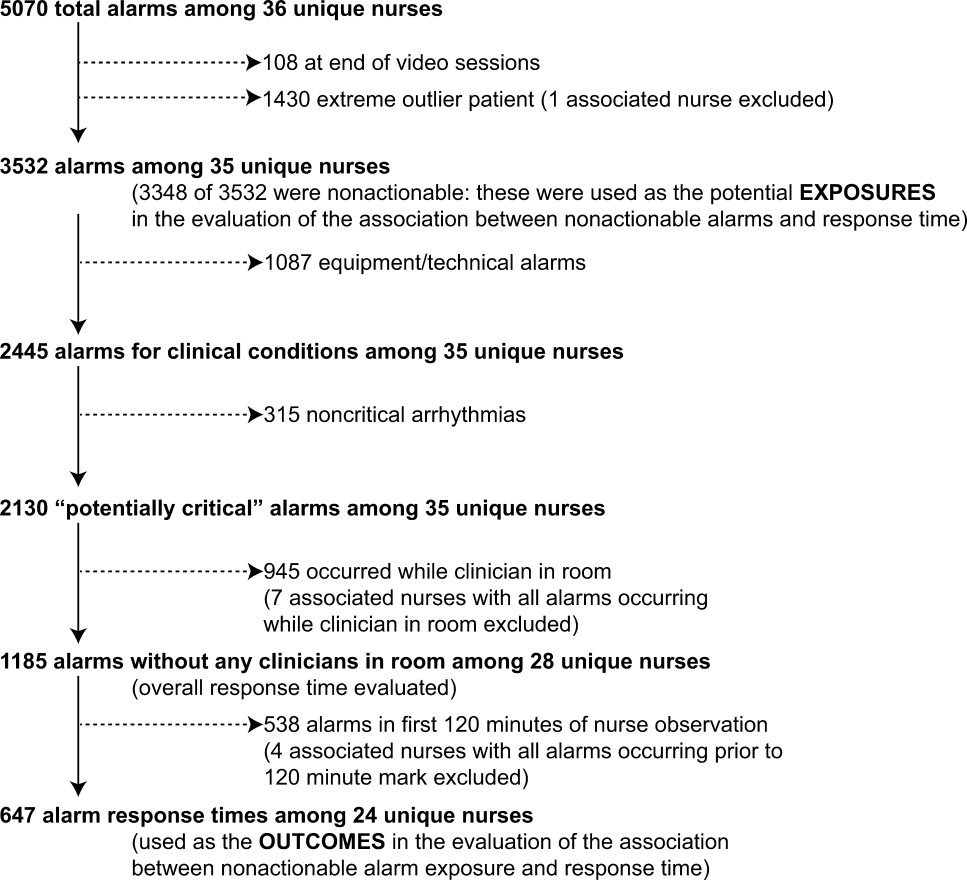

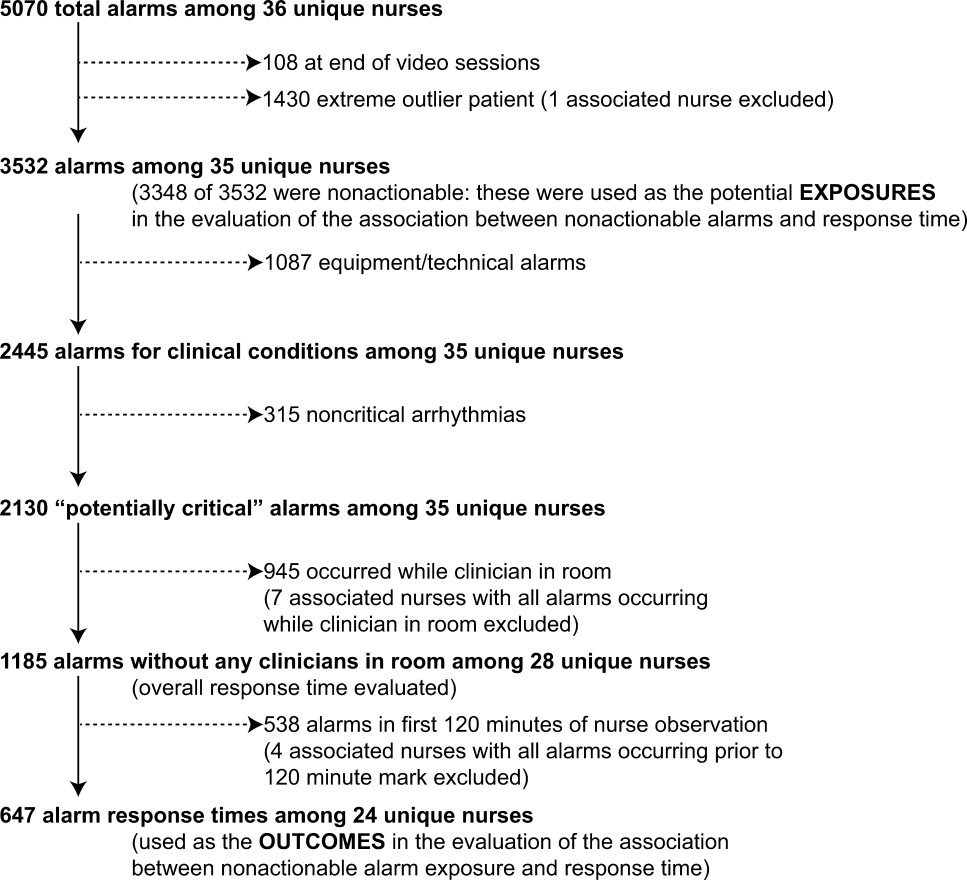

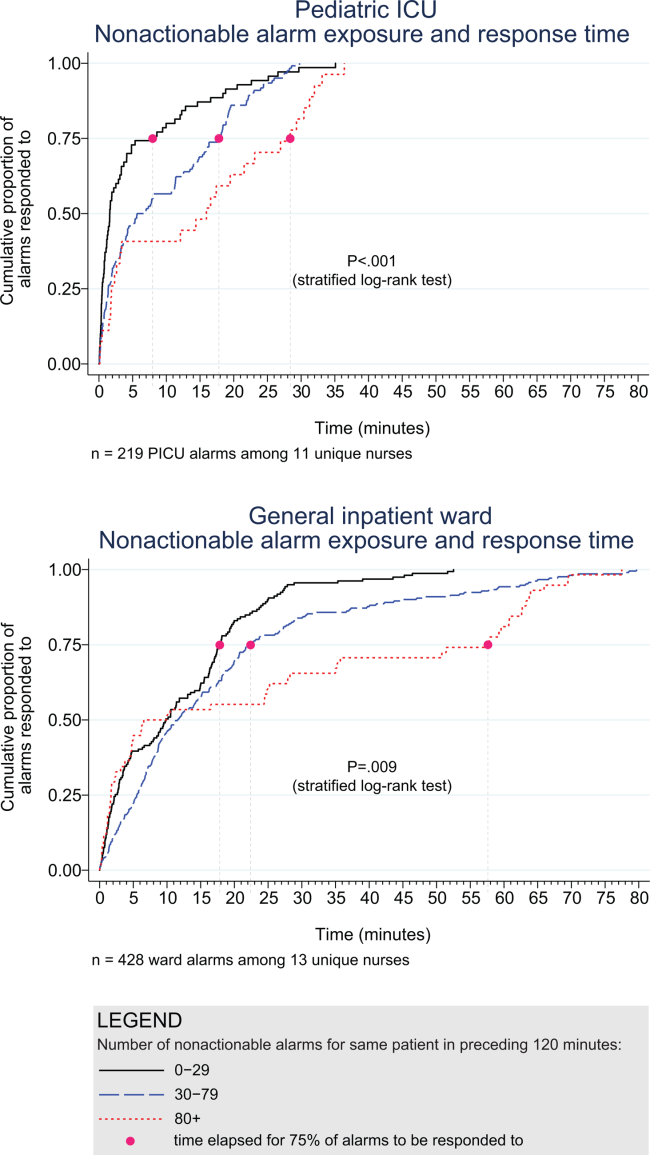

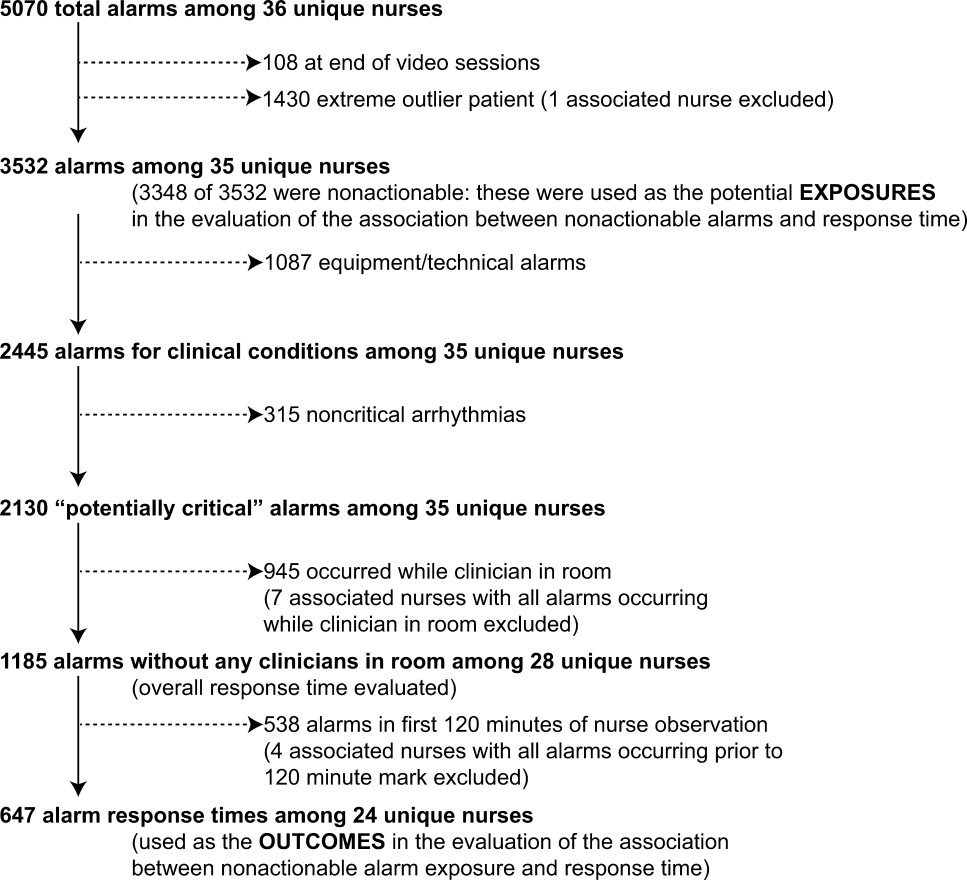

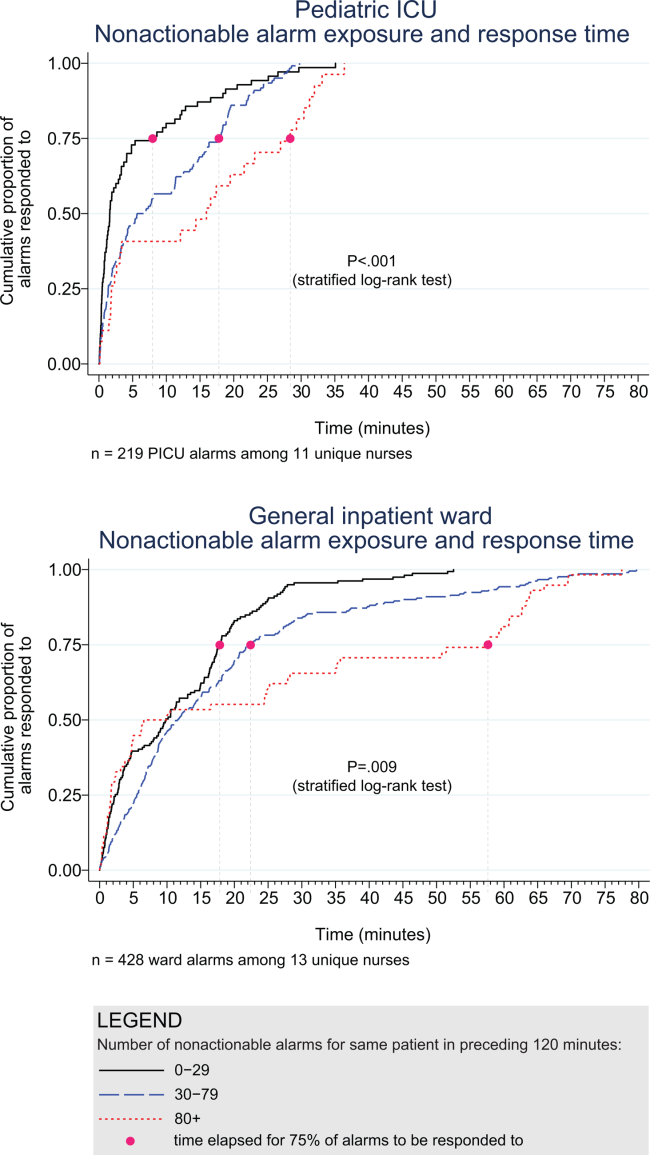

| Bonafide 2015[22] | Ward + ICU | 210 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5,070 | 13% PICU, 1% ward | Incremental increases in response time as number of nonactionable alarms in preceding 120 minutes increased | ✓ |

| Lawless 1994[23] | ICU | 928 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,176 | 6% | |||

| Rosman 2013[24] | ICU | 8,232 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 54,656 | 4% of rhythm alarms true critical" | ||

| Talley 2011[25] | ICU | 1,470∥ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,245 | 3% | ||

| Tsien 1997[26] | ICU | 298 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,942 | 8% | |||

| van Pul 2015[27] | ICU | 113,880∥ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 222,751 | Not reported | Assigned nurse did not respond to 6% of alarms within 45 seconds | |

| Varpio 2012[28] | Ward | 49 unit‐hours | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 446 | Not reported | 70% of all alarms and 41% of crisis alarms were not responded to within 1 minute | |

| Both | ||||||||||

| O'Carroll 1986[29] | ICU | 2,258∥ | ✓ | 284 | 2% | |||||

| Wiklund 1994[30] | PACU | 207 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1,891 | 17% | |||

Relationship Between Alarm Exposure and Response Time

Whereas 9 studies addressed response time,[8, 12, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 27, 28] only 2 evaluated the relationship between alarm burden and nurse response time.[20, 22] Voepel‐Lewis and colleagues found that nurse responses were slower to patients with the highest quartile of alarms (57.6 seconds) compared to those with the lowest (45.4 seconds) or medium (42.3 seconds) quartiles of alarms on an adult ward (P = 0.046). They did not find an association between false alarm exposure and response time.[20] Bonafide and colleagues found incremental increases in response time as the number of nonactionable alarms in the preceding 120 minutes increased (P < 0.001 in the pediatric ICU, P = 0.009 on the pediatric ward).[22]

Interventions Effective in Reducing Alarms

Results of the 8 intervention studies are provided in Table 3. Three studies evaluated single interventions;[32, 33, 36] the remainder of the studies tested interventions with multiple components such that it was impossible to separate the effect of each component. Below, we have summarized study results, arranged by component. Because only 1 study focused on pediatric patients,[38] results from pediatric and adult settings are combined.

| First Author and Publication Year | Design | Setting | Main Intervention Components | Other/ Comments | Key Results | Results Statistically Significant? | Lower Risk of Bias | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widen Default Settings | Alarm Delays | Reconfigure Alarm Acuity | Secondary Notification | ECG Changes | |||||||

| |||||||||||

| Adult | |||||||||||

| Albert 2015[32] | Experimental (cluster‐randomized) | CCU | ✓ | Disposable vs reusable wires | Disposable leads had 29% fewer no‐telemetry, leads‐fail, and leads‐off alarms and similar artifact alarms | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Cvach 2013[33] | Quasi‐experimental (before and after) | CCU and PCU | ✓ | Daily change of electrodes | 46% fewer alarms/bed/day | ||||||

| Cvach 2014[34] | Quasi‐experimental (ITS) | PCU | ✓* | ✓ | Slope of regression line suggests decrease of 0.75 alarms/bed/day | ||||||

| Graham 2010[35] | Quasi‐experimental (before and after) | PCU | ✓ | ✓ | 43% fewer crisis, warning, and system warning alarms on unit | ||||||

| Rheineck‐Leyssius 1997[36] | Experimental (RCT) | PACU | ✓ | ✓ | Alarm limit of 85% had fewer alarms/patient but higher incidence of true hypoxemia for >1 minute (6% vs 2%) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Taenzer 2010[31] | Quasi‐experimental (before and after with concurrent controls) | Ward | ✓ | ✓ | Universal SpO2 monitoring | Rescue events decreased from 3.4 to 1.2 per 1,000 discharges; transfers to ICU decreased from 5.6 to 2.9 per 1,000 patient‐days, only 4 alarms/patient‐day | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Whalen 2014[37] | Quasi‐experimental (before and after) | CCU | ✓ | ✓ | 89% fewer audible alarms on unit | ✓ | |||||

| Pediatric | |||||||||||

| Dandoy 2014[38] | Quasi‐experimental (ITS) | Ward | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Timely monitor discontinuation; daily change of ECG electrodes | Decrease in alarms/patient‐days from 180 to 40 | ✓ | |||

Widening alarm parameter default settings was evaluated in 5 studies:[31, 35, 36, 37, 38] 1 single intervention randomized controlled trial (RCT),[36] and 4 multiple‐intervention, quasi‐experimental studies.[31, 35, 37, 38] In the RCT, using a lower SpO2 limit of 85% instead of the standard 90% resulted in 61% fewer alarms. In the 4 multiple intervention studies, 1 study reported significant reductions in alarm rates (P < 0.001),[37] 1 study did not report preintervention alarm rates but reported a postintervention alarm rate of 4 alarms per patient‐day,[31] and 2 studies reported reductions in alarm rates but did not report any statistical testing.[35, 38] Of the 3 studies examining patient safety, 1 study with universal monitoring reported fewer rescue events and transfers to the ICU postimplementation,[31] 1 study reported no missed acute decompensations,[38] and 1 study (the RCT) reported significantly more true hypoxemia events (P = 0.001).[36]

Alarm delays were evaluated in 4 studies:[31, 34, 36, 38] 3 multiple‐intervention, quasi‐experimental studies[31, 34, 38] and 1 retrospective analysis of data from an RCT.[36] One study combined alarm delays with widening defaults in a universal monitoring strategy and reported a postintervention alarm rate of 4 alarms per patient.[31] Another study evaluated delays as part of a secondary notification pager system and found a negatively sloping regression line that suggested a decreasing alarm rate, but did not report statistical testing.[34] The third study reported a reduction in alarm rates but did not report statistical testing.[38] The RCT compared the impact of a hypothetical 15‐second alarm delay to that of a lower SpO2 limit reduction and reported a similar reduction in alarms.[36] Of the 4 studies examining patient safety, 1 study with universal monitoring reported improvements,[31] 2 studies reported no adverse outcomes,[35, 38] and the retrospective analysis of data from the RCT reported the theoretical adverse outcome of delayed detection of sudden, severe desaturations.[36]

Reconfiguring alarm acuity was evaluated in 2 studies, both of which were multiple‐intervention quasi‐experimental studies.[35, 37] Both showed reductions in alarm rates: 1 was significant without increasing adverse events (P < 0.001),[37] and the other did not report statistical testing or safety outcomes.[35]

Secondary notification of nurses using pagers was the main intervention component of 1 study incorporating delays between the alarms and the alarm pages.[34] As mentioned above, a negatively sloping regression line was displayed, but no statistical testing or safety outcomes were reported.

Disposable electrocardiographic lead wires or daily electrode changes were evaluated in 3 studies:[32, 33, 38] 1 single intervention cluster‐randomized trial[32] and 2 quasi‐experimental studies.[33, 38] In the cluster‐randomized trial, disposable lead wires were compared to reusable lead wires, with disposable lead wires having significantly fewer technical alarms for lead signal failures (P = 0.03) but a similar number of monitoring artifact alarms (P = 0.44).[32] In a single‐intervention, quasi‐experimental study, daily electrode change showed a reduction in alarms, but no statistical testing was reported.[33] One multiple‐intervention, quasi‐experimental study incorporating daily electrode change showed fewer alarms without statistical testing.[38] Of the 2 studies examining patient safety, both reported no adverse outcomes.[32, 38]

DISCUSSION

This systematic review of physiologic monitor alarms in the hospital yielded the following main findings: (1) between 74% and 99% of physiologic monitor alarms were not actionable, (2) a significant relationship between alarm exposure and nurse response time was demonstrated in 2 small observational studies, and (3) although interventions were most often studied in combination, results from the studies with lower risk of bias suggest that widening alarm parameters, implementing alarm delays, and using disposable electrocardiographic lead wires and/or changing electrodes daily are the most promising interventions for reducing alarms. Only 5 of 8 intervention studies measured intervention safety and found that widening alarm parameters and implementing alarm delays had mixed safety outcomes, whereas disposable electrocardiographic lead wires and daily electrode changes had no adverse safety outcomes.[29, 30, 34, 35, 36] Safety measures are crucial to ensuring the highest level of patient safety is met; interventions are rendered useless without ensuring actionable alarms are not disabled. The variation in results across studies likely reflects the wide range of care settings as well as differences in design and quality.

This field is still in its infancy, with 18 of the 32 articles published in the past 5 years. We anticipate improvements in quality and rigor as the field matures, as well as clinically tested interventions that incorporate smart alarms. Smart alarms integrate data from multiple physiologic signals and the patient's history to better detect physiologic changes in the patient and improve the positive predictive value of alarms. Academicindustry partnerships will be required to implement and rigorously test smart alarms and other emerging technologies in the hospital.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review focused on monitor alarms with specific review questions relevant to alarm fatigue. Cvach recently published an integrative review of alarm fatigue using research published through 2011.[39] Our review builds upon her work by contributing a more extensive and systematic search strategy with databases spanning nursing, medicine, and engineering, including additional languages, and including newer studies published through April 2015. In addition, we included multiple cross‐team checks in our eligibility review to ensure high sensitivity and specificity of the resulting set of studies.

Although we focused on interventions aiming to reduce alarms, there has also been important recent work focused on reducing telemetry utilization in adult hospital populations as well as work focused on reducing pulse oximetry utilization in children admitted with respiratory conditions. Dressler and colleagues reported an immediate and sustained reduction in telemetry utilization in hospitalized adults upon redesign of cardiac telemetry order sets to include the clinical indication, which defaulted to the American Heart Association guideline‐recommended telemetry duration.[40] Instructions for bedside nurses were also included in the order set to facilitate appropriate telemetry discontinuation. Schondelmeyer and colleagues reported reductions in continuous pulse oximetry utilization in hospitalized children with asthma and bronchiolitis upon introduction of a multifaceted quality improvement program that included provider education, a nurse handoff checklist, and discontinuation criteria incorporated into order sets.[41]

Limitations of This Review and the Underlying Body of Work

There are limitations to this systematic review and its underlying body of work. With respect to our approach to this systematic review, we focused only on monitor alarms. Numerous other medical devices generate alarms in the patient‐care environment that also can contribute to alarm fatigue and deserve equally rigorous evaluation. With respect to the underlying body of work, the quality of individual studies was generally low. For example, determinations of alarm actionability were often made by a single rater without evaluation of the reliability or validity of these determinations, and statistical testing was often missing. There were also limitations specific to intervention studies, including evaluation of nongeneralizable patient populations, failure to measure the fidelity of the interventions, inadequate measures of intervention safety, and failure to statistically evaluate alarm reductions. Finally, though not necessarily a limitation, several studies were conducted by authors involved in or funded by the medical device industry.[11, 15, 19, 31, 32] This has the potential to introduce bias, although we have no indication that the quality of the science was adversely impacted.

Moving forward, the research agenda for physiologic monitor alarms should include the following: (1) more intensive focus on evaluating the relationship between alarm exposure and response time with analysis of important mediating factors that may promote or prevent alarm fatigue, (2) emphasis on studying interventions aimed at improving alarm management using rigorous designs such as cluster‐randomized trials and trials randomized by individual participant, (3) monitoring and reporting clinically meaningful balancing measures that represent unintended consequences of disabling or delaying potentially important alarms and possibly reducing the clinicians' ability to detect true patient deterioration and intervene in a timely manner, and (4) support for transparent academicindustry partnerships to evaluate new alarm technology in real‐world settings. As evidence‐based interventions emerge, there will be new opportunities to study different implementation strategies of these interventions to optimize effectiveness.

CONCLUSIONS

The body of literature relevant to physiologic monitor alarm characteristics and alarm fatigue is limited but growing rapidly. Although we know that most alarms are not actionable and that there appears to be a relationship between alarm exposure and response time that could be caused by alarm fatigue, we cannot yet say with certainty that we know which interventions are most effective in safely reducing unnecessary alarms. Interventions that appear most promising and should be prioritized for intensive evaluation include widening alarm parameters, implementing alarm delays, and using disposable electrocardiographic lead wires and changing electrodes daily. Careful evaluation of these interventions must include systematically examining adverse patient safety consequences.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Amogh Karnik and Micheal Sellars for their technical assistance during the review and extraction process.

Disclosures: Ms. Zander is supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant. Dr. Bonafide and Ms. Stemler are supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23HL116427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- National Patient Safety Goals Effective January 1, 2015. The Joint Commission Web site. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2015_NPSG_HAP.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2015.

- ECRI Institute. 2015 Top 10 Health Technology Hazards. Available at: https://www.ecri.org/Pages/2015‐Hazards.aspx. Accessed June 23, 2015.

- , . Alarm fatigue: a patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2013;24(4):378–386.

- , . Redesigning hospital alarms for patient safety: alarmed and potentially dangerous. JAMA. 2014;311(12):1199–1200.

- , , , et al. Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta‐analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012.

- , , , ; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269, W64.

- , , , , . ALARMED: adverse events in low‐risk patients with chest pain receiving continuous electrocardiographic monitoring in the emergency department. A pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:62–67.

- , , . Patient and nurse‐related implications of remote cardiac telemetry. Clin Nurs Res. 2003;12(4):356–370.

- , , , , . Clinical evaluation of alarm efficiency in intensive care [in French]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2000;19:459–466.

- , , , , , . Multicentric study of monitoring alarms in the adult intensive care unit (ICU): a descriptive analysis. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:1360–1366.

- , , , et al. Insights into the problem of alarm fatigue with physiologic monitor devices: a comprehensive observational study of consecutive intensive care unit patients. PloS One. 2014;9(10):e110274.

- . Nurses' response to frequency and types of electrocardiography alarms in a non‐ critical care setting: a descriptive study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(2):190–197.

- , , . Improving alarm performance in the medical intensive care unit using delays and clinical context. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1546–1552.

- , , , et al. The proportion of clinically relevant alarms decreases as patient clinical severity decreases in intensive care units: a pilot study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003354–e003354.

- , , . Physiologic monitoring alarm load on medical/surgical floors of a community hospital. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2011;45:29–36.

- , , , . Frequency and reliability of alarms in the monitoring of cardiac postoperative patients. Int J Clin Monit Comput. 1990;7(2):129–133.

- , , , et al. Audit of the bedside monitor alarms in a critical care unit [in Spanish]. Enferm Intensiva. 2014;25(3):83–90.

- , . Stimulus‐response time to invasive blood pressure alarms: implications for the safety of critical‐care patients. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2014;35(2):135–141.

- , , , , , . Intensive care unit alarms— how many do we need? Crit Care Med. 2010;38:451–456.

- , , , et al. Pulse oximetry desaturation alarms on a general postoperative adult unit: a prospective observational study of nurse response time. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(10):1351–1358.

- , , . Whats that noise? Bedside monitoring in the Emergency Department. Int Emerg Nurs. 2014;22(4):197–201.

- , , , et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children's hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):345–351.

- . Crying wolf: false alarms in a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(6):981–985.

- , , , , . What are we missing? Arrhythmia detection in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2013;163(2):511–514.

- , , , et al. Cardiopulmonary monitors and clinically significant events in critically ill children. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2011;45(s1):38–45.

- , . Poor prognosis for existing monitors in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:614–619.

- , , , , . Safe patient monitoring is challenging but still feasible in a neonatal intensive care unit with single family rooms. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992. 2015;104(6):e247–e254.

- , , , . The helpful or hindering effects of in‐hospital patient monitor alarms on nurses: a qualitative analysis. CIN Comput Inform Nurs. 2012;30(4):210–217.

- . Survey of alarms in an intensive therapy unit. Anaesthesia. 1986;41(7):742–744.

- , , , . Postanesthesia monitoring revisited: frequency of true and false alarms from different monitoring devices. J Clin Anesth. 1994;6(3):182–188.

- , , , . Impact of pulse oximetry surveillance on rescue events and intensive care unit transfers: a before‐and‐after concurrence study. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(2):282–287.

- , , , et al. Differences in alarm events between disposable and reusable electrocardiography lead wires. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(1):67–74.

- , , , . Daily electrode change and effect on cardiac monitor alarms: an evidence‐based practice approach. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013;28:265–271.

- , , , . Use of pagers with an alarm escalation system to reduce cardiac monitor alarm signals. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014;29(1):9–18.

- , . Monitor alarm fatigue: standardizing use of physiological monitors and decreasing nuisance alarms. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19:28–34.

- , . Influence of pulse oximeter lower alarm limit on the incidence of hypoxaemia in the recovery room. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79(4):460–464.

- , , , , , . Novel approach to cardiac alarm management on telemetry units. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29(5):E13–E22.

- , , , et al. A team‐based approach to reducing cardiac monitor alarms. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):e1686–e1694.

- . Monitor alarm fatigue: an integrative review. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2012;46(4):268–277.

- , , , , . Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non‐intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852–1854.

- , , , et al. Using quality improvement to reduce continuous pulse oximetry use in children with wheezing. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):e1044–e1051.

- , . The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non‐randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384.

Clinical alarm safety has become a recent target for improvement in many hospitals. In 2013, The Joint Commission released a National Patient Safety Goal prompting accredited hospitals to establish alarm safety as a hospital priority, identify the most important alarm signals to manage, and, by 2016, develop policies and procedures that address alarm management.[1] In addition, the Emergency Care Research Institute has named alarm hazards the top health technology hazard each year since 2012.[2]

The primary arguments supporting the elevation of alarm management to a national hospital priority in the United States include the following: (1) clinicians rely on alarms to notify them of important physiologic changes, (2) alarms occur frequently and usually do not warrant clinical intervention, and (3) alarm overload renders clinicians unable to respond to all alarms, resulting in alarm fatigue: responding more slowly or ignoring alarms that may represent actual clinical deterioration.[3, 4] These arguments are built largely on anecdotal data, reported safety event databases, and small studies that have not previously been systematically analyzed.

Despite the national focus on alarms, we still know very little about fundamental questions key to improving alarm safety. In this systematic review, we aimed to answer 3 key questions about physiologic monitor alarms: (1) What proportion of alarms warrant attention or clinical intervention (ie, actionable alarms), and how does this proportion vary between adult and pediatric populations and between intensive care unit (ICU) and ward settings? (2) What is the relationship between alarm exposure and clinician response time? (3) What interventions are effective in reducing the frequency of alarms?

We limited our scope to monitor alarms because few studies have evaluated the characteristics of alarms from other medical devices, and because missing relevant monitor alarms could adversely impact patient safety.

METHODS

We performed a systematic review of the literature in accordance with the Meta‐Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines[5] and developed this manuscript using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement.[6]

Eligibility Criteria

With help from an experienced biomedical librarian (C.D.S.), we searched PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Scopus, Cochrane Library,

We included peer‐reviewed, original research studies published in English, Spanish, or French that addressed the questions outlined above. Eligible patient populations were children and adults admitted to hospital inpatient units and emergency departments (EDs). We excluded alarms in procedural suites or operating rooms (typically responded to by anesthesiologists already with the patient) because of the differences in environment of care, staff‐to‐patient ratio, and equipment. We included observational studies reporting the actionability of physiologic monitor alarms (ie, alarms warranting special attention or clinical intervention), as well as nurse responses to these alarms. We excluded studies focused on the effects of alarms unrelated to patient safety, such as families' and patients' stress, noise, or sleep disturbance. We included only intervention studies evaluating pragmatic interventions ready for clinical implementation (ie, not experimental devices or software algorithms).

Selection Process and Data Extraction

First, 2 authors screened the titles and abstracts of articles for eligibility. To maximize sensitivity, if at least 1 author considered the article relevant, the article proceeded to full‐text review. Second, the full texts of articles screened were independently reviewed by 2 authors in an unblinded fashion to determine their eligibility. Any disagreements concerning eligibility were resolved by team consensus. To assure consistency in eligibility determinations across the team, a core group of the authors (C.W.P, C.P.B., E.E., and V.V.G.) held a series of meetings to review and discuss each potentially eligible article and reach consensus on the final list of included articles. Two authors independently extracted the following characteristics from included studies: alarm review methods, analytic design, fidelity measurement, consideration of unintended adverse safety consequences, and key results. Reviewers were not blinded to journal, authors, or affiliations.

Synthesis of Results and Risk Assessment

Given the high degree of heterogeneity in methodology, we were unable to generate summary proportions of the observational studies or perform a meta‐analysis of the intervention studies. Thus, we organized the studies into clinically relevant categories and presented key aspects in tables. Due to the heterogeneity of the studies and the controversy surrounding quality scores,[5] we did not generate summary scores of study quality. Instead, we evaluated and reported key design elements that had the potential to bias the results. To recognize the more comprehensive studies in the field, we developed by consensus a set of characteristics that distinguished studies with lower risk of bias. These characteristics are shown and defined in Table 1.

| First Author and Publication Year | Alarm Review Method | Indicators of Potential Bias for Observational Studies | Indicators of Potential Bias for Intervention Studies | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitor System | Direct Observation | Medical Record Review | Rhythm Annotation | Video Observation | Remote Monitoring Staff | Medical Device Industry Involved | Two Independent Reviewers | At Least 1 Reviewer Is a Clinical Expert | Reviewer Not Simultaneously in Patient Care | Clear Definition of Alarm Actionability | Census Included | Statistical Testing or QI SPC Methods | Fidelity Assessed | Safety Assessed | Lower Risk of Bias | |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Adult Observational | ||||||||||||||||

| Atzema 2006[7] | ✓* | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Billinghurst 2003[8] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Biot 2000[9] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Chambrin 1999[10] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Drew 2014[11] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gazarian 2014[12] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Grges 2009[13] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Gross 2011[15] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Inokuchi 2013[14] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Koski 1990[16] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Morales Snchez 2014[17] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Pergher 2014[18] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Siebig 2010[19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Voepel‐Lewis 2013[20] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Way 2014[21] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Pediatric Observational | ||||||||||||||||

| Bonafide 2015[22] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lawless 1994[23] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Rosman 2013[24] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Talley 2011[25] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Tsien 1997[26] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| van Pul 2015[27] | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Varpio 2012[28] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mixed Adult and Pediatric Observational | ||||||||||||||||

| O'Carroll 1986[29] | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Wiklund 1994[30] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Adult Intervention | ||||||||||||||||

| Albert 2015[32] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cvach 2013[33] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Cvach 2014[34] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Graham 2010[35] | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Rheineck‐Leyssius 1997[36] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Taenzer 2010[31] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Whalen 2014[37] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Pediatric Intervention | ||||||||||||||||

| Dandoy 2014[38] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

For the purposes of this review, we defined nonactionable alarms as including both invalid (false) alarms that do not that accurately represent the physiologic status of the patient and alarms that are valid but do not warrant special attention or clinical intervention (nuisance alarms). We did not separate out invalid alarms due to the tremendous variation between studies in how validity was measured.

RESULTS

Study Selection

Search results produced 4629 articles (see the flow diagram in the Supporting Information in the online version of this article), of which 32 articles were eligible: 24 observational studies describing alarm characteristics and 8 studies describing interventions to reduce alarm frequency.

Observational Study Characteristics

Characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 1. Of the 24 observational studies,[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] 15 included adult patients,[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21] 7 included pediatric patients,[22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28] and 2 included both adult and pediatric patients.[29, 30] All were single‐hospital studies, except for 1 study by Chambrin and colleagues[10] that included 5 sites. The number of patient‐hours examined in each study ranged from 60 to 113,880.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30] Hospital settings included ICUs (n = 16),[9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29] general wards (n = 5),[12, 15, 20, 22, 28] EDs (n = 2),[7, 21] postanesthesia care unit (PACU) (n = 1),[30] and cardiac care unit (CCU) (n = 1).[8] Studies varied in the type of physiologic signals recorded and data collection methods, ranging from direct observation by a nurse who was simultaneously caring for patients[29] to video recording with expert review.[14, 19, 22] Four observational studies met the criteria for lower risk of bias.[11, 14, 15, 22]

Intervention Study Characteristics

Of the 8 intervention studies, 7 included adult patients,[31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37] and 1 included pediatric patients.[38] All were single‐hospital studies; 6 were quasi‐experimental[31, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38] and 2 were experimental.[32, 36] Settings included progressive care units (n = 3),[33, 34, 35] CCUs (n = 3),[32, 33, 37] wards (n = 2),[31, 38] PACU (n = 1),[36] and a step‐down unit (n = 1).[32] All except 1 study[32] used the monitoring system to record alarm data. Several studies evaluated multicomponent interventions that included combinations of the following: widening alarm parameters,[31, 35, 36, 37, 38] instituting alarm delays,[31, 34, 36, 38] reconfiguring alarm acuity,[35, 37] use of secondary notifications,[34] daily change of electrocardiographic electrodes or use of disposable electrocardiographic wires,[32, 33, 38] universal monitoring in high‐risk populations,[31] and timely discontinuation of monitoring in low‐risk populations.[38] Four intervention studies met our prespecified lower risk of bias criteria.[31, 32, 36, 38]

Proportion of Alarms Considered Actionable

Results of the observational studies are provided in Table 2. The proportion of alarms that were actionable was <1% to 26% in adult ICU settings,[9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 19] 20% to 36% in adult ward settings,[12, 15, 20] 17% in a mixed adult and pediatric PACU setting,[30] 3% to 13% in pediatric ICU settings,[22, 23, 24, 25, 26] and 1% in a pediatric ward setting.[22]

| Signals Included | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Author and Publication Year | Setting | Monitored Patient‐Hours | SpO2 | ECG Arrhythmia | ECG Parametersa | Blood Pressure | Total Alarms | Actionable Alarms | Alarm Response | Lower Risk of Bias |

| ||||||||||

| Adult | ||||||||||

| Atzema 2006[7] | ED | 371 | ✓ | 1,762 | 0.20% | |||||

| Billinghurst 2003[8] | CCU | 420 | ✓ | 751 | Not reported; 17% were valid | Nurses with higher acuity patients and smaller % of valid alarms had slower response rates | ||||

| Biot 2000[9] | ICU | 250 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3,665 | 3% | ||

| Chambrin 1999[10] | ICU | 1,971 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3,188 | 26% | ||

| Drew 2014[11] | ICU | 48,173 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,558,760 | 0.3% of 3,861 VT alarms | ✓ | |

| Gazarian 2014[12] | Ward | 54 nurse‐hours | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 205 | 22% | Response to 47% of alarms | ||

| Grges 2009[13] | ICU | 200 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1,214 | 5% | ||

| Gross 2011[15] | Ward | 530 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4,393 | 20% | ✓ | |

| Inokuchi 2013[14] | ICU | 2,697 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 11,591 | 6% | ✓ | |

| Koski 1990[16] | ICU | 400 | ✓ | ✓ | 2,322 | 12% | ||||

| Morales Snchez 2014[17] | ICU | 434 sessions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 215 | 25% | Response to 93% of alarms, of which 50% were within 10 seconds | ||

| Pergher 2014[18] | ICU | 60 | ✓ | 76 | Not reported | 72% of alarms stopped before nurse response or had >10 minutes response time | ||||

| Siebig 2010[19] | ICU | 982 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5,934 | 15% | ||

| Voepel‐Lewis 2013[20] | Ward | 1,616 | ✓ | 710 | 36% | Response time was longer for patients in highest quartile of total alarms | ||||

| Way 2014[21] | ED | 93 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 572 | Not reported; 75% were valid | Nurses responded to more alarms in resuscitation room vs acute care area, but response time was longer | |

| Pediatric | ||||||||||

| Bonafide 2015[22] | Ward + ICU | 210 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5,070 | 13% PICU, 1% ward | Incremental increases in response time as number of nonactionable alarms in preceding 120 minutes increased | ✓ |

| Lawless 1994[23] | ICU | 928 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,176 | 6% | |||

| Rosman 2013[24] | ICU | 8,232 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 54,656 | 4% of rhythm alarms true critical" | ||

| Talley 2011[25] | ICU | 1,470∥ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,245 | 3% | ||

| Tsien 1997[26] | ICU | 298 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,942 | 8% | |||

| van Pul 2015[27] | ICU | 113,880∥ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 222,751 | Not reported | Assigned nurse did not respond to 6% of alarms within 45 seconds | |

| Varpio 2012[28] | Ward | 49 unit‐hours | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 446 | Not reported | 70% of all alarms and 41% of crisis alarms were not responded to within 1 minute | |

| Both | ||||||||||

| O'Carroll 1986[29] | ICU | 2,258∥ | ✓ | 284 | 2% | |||||

| Wiklund 1994[30] | PACU | 207 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1,891 | 17% | |||

Relationship Between Alarm Exposure and Response Time

Whereas 9 studies addressed response time,[8, 12, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 27, 28] only 2 evaluated the relationship between alarm burden and nurse response time.[20, 22] Voepel‐Lewis and colleagues found that nurse responses were slower to patients with the highest quartile of alarms (57.6 seconds) compared to those with the lowest (45.4 seconds) or medium (42.3 seconds) quartiles of alarms on an adult ward (P = 0.046). They did not find an association between false alarm exposure and response time.[20] Bonafide and colleagues found incremental increases in response time as the number of nonactionable alarms in the preceding 120 minutes increased (P < 0.001 in the pediatric ICU, P = 0.009 on the pediatric ward).[22]

Interventions Effective in Reducing Alarms

Results of the 8 intervention studies are provided in Table 3. Three studies evaluated single interventions;[32, 33, 36] the remainder of the studies tested interventions with multiple components such that it was impossible to separate the effect of each component. Below, we have summarized study results, arranged by component. Because only 1 study focused on pediatric patients,[38] results from pediatric and adult settings are combined.

| First Author and Publication Year | Design | Setting | Main Intervention Components | Other/ Comments | Key Results | Results Statistically Significant? | Lower Risk of Bias | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widen Default Settings | Alarm Delays | Reconfigure Alarm Acuity | Secondary Notification | ECG Changes | |||||||

| |||||||||||

| Adult | |||||||||||

| Albert 2015[32] | Experimental (cluster‐randomized) | CCU | ✓ | Disposable vs reusable wires | Disposable leads had 29% fewer no‐telemetry, leads‐fail, and leads‐off alarms and similar artifact alarms | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Cvach 2013[33] | Quasi‐experimental (before and after) | CCU and PCU | ✓ | Daily change of electrodes | 46% fewer alarms/bed/day | ||||||

| Cvach 2014[34] | Quasi‐experimental (ITS) | PCU | ✓* | ✓ | Slope of regression line suggests decrease of 0.75 alarms/bed/day | ||||||

| Graham 2010[35] | Quasi‐experimental (before and after) | PCU | ✓ | ✓ | 43% fewer crisis, warning, and system warning alarms on unit | ||||||

| Rheineck‐Leyssius 1997[36] | Experimental (RCT) | PACU | ✓ | ✓ | Alarm limit of 85% had fewer alarms/patient but higher incidence of true hypoxemia for >1 minute (6% vs 2%) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Taenzer 2010[31] | Quasi‐experimental (before and after with concurrent controls) | Ward | ✓ | ✓ | Universal SpO2 monitoring | Rescue events decreased from 3.4 to 1.2 per 1,000 discharges; transfers to ICU decreased from 5.6 to 2.9 per 1,000 patient‐days, only 4 alarms/patient‐day | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Whalen 2014[37] | Quasi‐experimental (before and after) | CCU | ✓ | ✓ | 89% fewer audible alarms on unit | ✓ | |||||

| Pediatric | |||||||||||

| Dandoy 2014[38] | Quasi‐experimental (ITS) | Ward | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Timely monitor discontinuation; daily change of ECG electrodes | Decrease in alarms/patient‐days from 180 to 40 | ✓ | |||

Widening alarm parameter default settings was evaluated in 5 studies:[31, 35, 36, 37, 38] 1 single intervention randomized controlled trial (RCT),[36] and 4 multiple‐intervention, quasi‐experimental studies.[31, 35, 37, 38] In the RCT, using a lower SpO2 limit of 85% instead of the standard 90% resulted in 61% fewer alarms. In the 4 multiple intervention studies, 1 study reported significant reductions in alarm rates (P < 0.001),[37] 1 study did not report preintervention alarm rates but reported a postintervention alarm rate of 4 alarms per patient‐day,[31] and 2 studies reported reductions in alarm rates but did not report any statistical testing.[35, 38] Of the 3 studies examining patient safety, 1 study with universal monitoring reported fewer rescue events and transfers to the ICU postimplementation,[31] 1 study reported no missed acute decompensations,[38] and 1 study (the RCT) reported significantly more true hypoxemia events (P = 0.001).[36]

Alarm delays were evaluated in 4 studies:[31, 34, 36, 38] 3 multiple‐intervention, quasi‐experimental studies[31, 34, 38] and 1 retrospective analysis of data from an RCT.[36] One study combined alarm delays with widening defaults in a universal monitoring strategy and reported a postintervention alarm rate of 4 alarms per patient.[31] Another study evaluated delays as part of a secondary notification pager system and found a negatively sloping regression line that suggested a decreasing alarm rate, but did not report statistical testing.[34] The third study reported a reduction in alarm rates but did not report statistical testing.[38] The RCT compared the impact of a hypothetical 15‐second alarm delay to that of a lower SpO2 limit reduction and reported a similar reduction in alarms.[36] Of the 4 studies examining patient safety, 1 study with universal monitoring reported improvements,[31] 2 studies reported no adverse outcomes,[35, 38] and the retrospective analysis of data from the RCT reported the theoretical adverse outcome of delayed detection of sudden, severe desaturations.[36]

Reconfiguring alarm acuity was evaluated in 2 studies, both of which were multiple‐intervention quasi‐experimental studies.[35, 37] Both showed reductions in alarm rates: 1 was significant without increasing adverse events (P < 0.001),[37] and the other did not report statistical testing or safety outcomes.[35]

Secondary notification of nurses using pagers was the main intervention component of 1 study incorporating delays between the alarms and the alarm pages.[34] As mentioned above, a negatively sloping regression line was displayed, but no statistical testing or safety outcomes were reported.

Disposable electrocardiographic lead wires or daily electrode changes were evaluated in 3 studies:[32, 33, 38] 1 single intervention cluster‐randomized trial[32] and 2 quasi‐experimental studies.[33, 38] In the cluster‐randomized trial, disposable lead wires were compared to reusable lead wires, with disposable lead wires having significantly fewer technical alarms for lead signal failures (P = 0.03) but a similar number of monitoring artifact alarms (P = 0.44).[32] In a single‐intervention, quasi‐experimental study, daily electrode change showed a reduction in alarms, but no statistical testing was reported.[33] One multiple‐intervention, quasi‐experimental study incorporating daily electrode change showed fewer alarms without statistical testing.[38] Of the 2 studies examining patient safety, both reported no adverse outcomes.[32, 38]

DISCUSSION

This systematic review of physiologic monitor alarms in the hospital yielded the following main findings: (1) between 74% and 99% of physiologic monitor alarms were not actionable, (2) a significant relationship between alarm exposure and nurse response time was demonstrated in 2 small observational studies, and (3) although interventions were most often studied in combination, results from the studies with lower risk of bias suggest that widening alarm parameters, implementing alarm delays, and using disposable electrocardiographic lead wires and/or changing electrodes daily are the most promising interventions for reducing alarms. Only 5 of 8 intervention studies measured intervention safety and found that widening alarm parameters and implementing alarm delays had mixed safety outcomes, whereas disposable electrocardiographic lead wires and daily electrode changes had no adverse safety outcomes.[29, 30, 34, 35, 36] Safety measures are crucial to ensuring the highest level of patient safety is met; interventions are rendered useless without ensuring actionable alarms are not disabled. The variation in results across studies likely reflects the wide range of care settings as well as differences in design and quality.

This field is still in its infancy, with 18 of the 32 articles published in the past 5 years. We anticipate improvements in quality and rigor as the field matures, as well as clinically tested interventions that incorporate smart alarms. Smart alarms integrate data from multiple physiologic signals and the patient's history to better detect physiologic changes in the patient and improve the positive predictive value of alarms. Academicindustry partnerships will be required to implement and rigorously test smart alarms and other emerging technologies in the hospital.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review focused on monitor alarms with specific review questions relevant to alarm fatigue. Cvach recently published an integrative review of alarm fatigue using research published through 2011.[39] Our review builds upon her work by contributing a more extensive and systematic search strategy with databases spanning nursing, medicine, and engineering, including additional languages, and including newer studies published through April 2015. In addition, we included multiple cross‐team checks in our eligibility review to ensure high sensitivity and specificity of the resulting set of studies.

Although we focused on interventions aiming to reduce alarms, there has also been important recent work focused on reducing telemetry utilization in adult hospital populations as well as work focused on reducing pulse oximetry utilization in children admitted with respiratory conditions. Dressler and colleagues reported an immediate and sustained reduction in telemetry utilization in hospitalized adults upon redesign of cardiac telemetry order sets to include the clinical indication, which defaulted to the American Heart Association guideline‐recommended telemetry duration.[40] Instructions for bedside nurses were also included in the order set to facilitate appropriate telemetry discontinuation. Schondelmeyer and colleagues reported reductions in continuous pulse oximetry utilization in hospitalized children with asthma and bronchiolitis upon introduction of a multifaceted quality improvement program that included provider education, a nurse handoff checklist, and discontinuation criteria incorporated into order sets.[41]

Limitations of This Review and the Underlying Body of Work

There are limitations to this systematic review and its underlying body of work. With respect to our approach to this systematic review, we focused only on monitor alarms. Numerous other medical devices generate alarms in the patient‐care environment that also can contribute to alarm fatigue and deserve equally rigorous evaluation. With respect to the underlying body of work, the quality of individual studies was generally low. For example, determinations of alarm actionability were often made by a single rater without evaluation of the reliability or validity of these determinations, and statistical testing was often missing. There were also limitations specific to intervention studies, including evaluation of nongeneralizable patient populations, failure to measure the fidelity of the interventions, inadequate measures of intervention safety, and failure to statistically evaluate alarm reductions. Finally, though not necessarily a limitation, several studies were conducted by authors involved in or funded by the medical device industry.[11, 15, 19, 31, 32] This has the potential to introduce bias, although we have no indication that the quality of the science was adversely impacted.

Moving forward, the research agenda for physiologic monitor alarms should include the following: (1) more intensive focus on evaluating the relationship between alarm exposure and response time with analysis of important mediating factors that may promote or prevent alarm fatigue, (2) emphasis on studying interventions aimed at improving alarm management using rigorous designs such as cluster‐randomized trials and trials randomized by individual participant, (3) monitoring and reporting clinically meaningful balancing measures that represent unintended consequences of disabling or delaying potentially important alarms and possibly reducing the clinicians' ability to detect true patient deterioration and intervene in a timely manner, and (4) support for transparent academicindustry partnerships to evaluate new alarm technology in real‐world settings. As evidence‐based interventions emerge, there will be new opportunities to study different implementation strategies of these interventions to optimize effectiveness.

CONCLUSIONS

The body of literature relevant to physiologic monitor alarm characteristics and alarm fatigue is limited but growing rapidly. Although we know that most alarms are not actionable and that there appears to be a relationship between alarm exposure and response time that could be caused by alarm fatigue, we cannot yet say with certainty that we know which interventions are most effective in safely reducing unnecessary alarms. Interventions that appear most promising and should be prioritized for intensive evaluation include widening alarm parameters, implementing alarm delays, and using disposable electrocardiographic lead wires and changing electrodes daily. Careful evaluation of these interventions must include systematically examining adverse patient safety consequences.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Amogh Karnik and Micheal Sellars for their technical assistance during the review and extraction process.

Disclosures: Ms. Zander is supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant. Dr. Bonafide and Ms. Stemler are supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23HL116427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Clinical alarm safety has become a recent target for improvement in many hospitals. In 2013, The Joint Commission released a National Patient Safety Goal prompting accredited hospitals to establish alarm safety as a hospital priority, identify the most important alarm signals to manage, and, by 2016, develop policies and procedures that address alarm management.[1] In addition, the Emergency Care Research Institute has named alarm hazards the top health technology hazard each year since 2012.[2]

The primary arguments supporting the elevation of alarm management to a national hospital priority in the United States include the following: (1) clinicians rely on alarms to notify them of important physiologic changes, (2) alarms occur frequently and usually do not warrant clinical intervention, and (3) alarm overload renders clinicians unable to respond to all alarms, resulting in alarm fatigue: responding more slowly or ignoring alarms that may represent actual clinical deterioration.[3, 4] These arguments are built largely on anecdotal data, reported safety event databases, and small studies that have not previously been systematically analyzed.

Despite the national focus on alarms, we still know very little about fundamental questions key to improving alarm safety. In this systematic review, we aimed to answer 3 key questions about physiologic monitor alarms: (1) What proportion of alarms warrant attention or clinical intervention (ie, actionable alarms), and how does this proportion vary between adult and pediatric populations and between intensive care unit (ICU) and ward settings? (2) What is the relationship between alarm exposure and clinician response time? (3) What interventions are effective in reducing the frequency of alarms?

We limited our scope to monitor alarms because few studies have evaluated the characteristics of alarms from other medical devices, and because missing relevant monitor alarms could adversely impact patient safety.

METHODS

We performed a systematic review of the literature in accordance with the Meta‐Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines[5] and developed this manuscript using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement.[6]

Eligibility Criteria

With help from an experienced biomedical librarian (C.D.S.), we searched PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Scopus, Cochrane Library,

We included peer‐reviewed, original research studies published in English, Spanish, or French that addressed the questions outlined above. Eligible patient populations were children and adults admitted to hospital inpatient units and emergency departments (EDs). We excluded alarms in procedural suites or operating rooms (typically responded to by anesthesiologists already with the patient) because of the differences in environment of care, staff‐to‐patient ratio, and equipment. We included observational studies reporting the actionability of physiologic monitor alarms (ie, alarms warranting special attention or clinical intervention), as well as nurse responses to these alarms. We excluded studies focused on the effects of alarms unrelated to patient safety, such as families' and patients' stress, noise, or sleep disturbance. We included only intervention studies evaluating pragmatic interventions ready for clinical implementation (ie, not experimental devices or software algorithms).

Selection Process and Data Extraction

First, 2 authors screened the titles and abstracts of articles for eligibility. To maximize sensitivity, if at least 1 author considered the article relevant, the article proceeded to full‐text review. Second, the full texts of articles screened were independently reviewed by 2 authors in an unblinded fashion to determine their eligibility. Any disagreements concerning eligibility were resolved by team consensus. To assure consistency in eligibility determinations across the team, a core group of the authors (C.W.P, C.P.B., E.E., and V.V.G.) held a series of meetings to review and discuss each potentially eligible article and reach consensus on the final list of included articles. Two authors independently extracted the following characteristics from included studies: alarm review methods, analytic design, fidelity measurement, consideration of unintended adverse safety consequences, and key results. Reviewers were not blinded to journal, authors, or affiliations.

Synthesis of Results and Risk Assessment

Given the high degree of heterogeneity in methodology, we were unable to generate summary proportions of the observational studies or perform a meta‐analysis of the intervention studies. Thus, we organized the studies into clinically relevant categories and presented key aspects in tables. Due to the heterogeneity of the studies and the controversy surrounding quality scores,[5] we did not generate summary scores of study quality. Instead, we evaluated and reported key design elements that had the potential to bias the results. To recognize the more comprehensive studies in the field, we developed by consensus a set of characteristics that distinguished studies with lower risk of bias. These characteristics are shown and defined in Table 1.

| First Author and Publication Year | Alarm Review Method | Indicators of Potential Bias for Observational Studies | Indicators of Potential Bias for Intervention Studies | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitor System | Direct Observation | Medical Record Review | Rhythm Annotation | Video Observation | Remote Monitoring Staff | Medical Device Industry Involved | Two Independent Reviewers | At Least 1 Reviewer Is a Clinical Expert | Reviewer Not Simultaneously in Patient Care | Clear Definition of Alarm Actionability | Census Included | Statistical Testing or QI SPC Methods | Fidelity Assessed | Safety Assessed | Lower Risk of Bias | |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Adult Observational | ||||||||||||||||

| Atzema 2006[7] | ✓* | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Billinghurst 2003[8] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Biot 2000[9] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Chambrin 1999[10] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Drew 2014[11] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gazarian 2014[12] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Grges 2009[13] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Gross 2011[15] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Inokuchi 2013[14] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Koski 1990[16] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Morales Snchez 2014[17] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Pergher 2014[18] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Siebig 2010[19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Voepel‐Lewis 2013[20] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Way 2014[21] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Pediatric Observational | ||||||||||||||||

| Bonafide 2015[22] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lawless 1994[23] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Rosman 2013[24] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Talley 2011[25] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Tsien 1997[26] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| van Pul 2015[27] | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Varpio 2012[28] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mixed Adult and Pediatric Observational | ||||||||||||||||

| O'Carroll 1986[29] | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Wiklund 1994[30] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Adult Intervention | ||||||||||||||||

| Albert 2015[32] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cvach 2013[33] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Cvach 2014[34] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Graham 2010[35] | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Rheineck‐Leyssius 1997[36] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Taenzer 2010[31] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Whalen 2014[37] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Pediatric Intervention | ||||||||||||||||

| Dandoy 2014[38] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

For the purposes of this review, we defined nonactionable alarms as including both invalid (false) alarms that do not that accurately represent the physiologic status of the patient and alarms that are valid but do not warrant special attention or clinical intervention (nuisance alarms). We did not separate out invalid alarms due to the tremendous variation between studies in how validity was measured.

RESULTS

Study Selection

Search results produced 4629 articles (see the flow diagram in the Supporting Information in the online version of this article), of which 32 articles were eligible: 24 observational studies describing alarm characteristics and 8 studies describing interventions to reduce alarm frequency.

Observational Study Characteristics

Characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 1. Of the 24 observational studies,[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] 15 included adult patients,[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21] 7 included pediatric patients,[22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28] and 2 included both adult and pediatric patients.[29, 30] All were single‐hospital studies, except for 1 study by Chambrin and colleagues[10] that included 5 sites. The number of patient‐hours examined in each study ranged from 60 to 113,880.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30] Hospital settings included ICUs (n = 16),[9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29] general wards (n = 5),[12, 15, 20, 22, 28] EDs (n = 2),[7, 21] postanesthesia care unit (PACU) (n = 1),[30] and cardiac care unit (CCU) (n = 1).[8] Studies varied in the type of physiologic signals recorded and data collection methods, ranging from direct observation by a nurse who was simultaneously caring for patients[29] to video recording with expert review.[14, 19, 22] Four observational studies met the criteria for lower risk of bias.[11, 14, 15, 22]

Intervention Study Characteristics

Of the 8 intervention studies, 7 included adult patients,[31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37] and 1 included pediatric patients.[38] All were single‐hospital studies; 6 were quasi‐experimental[31, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38] and 2 were experimental.[32, 36] Settings included progressive care units (n = 3),[33, 34, 35] CCUs (n = 3),[32, 33, 37] wards (n = 2),[31, 38] PACU (n = 1),[36] and a step‐down unit (n = 1).[32] All except 1 study[32] used the monitoring system to record alarm data. Several studies evaluated multicomponent interventions that included combinations of the following: widening alarm parameters,[31, 35, 36, 37, 38] instituting alarm delays,[31, 34, 36, 38] reconfiguring alarm acuity,[35, 37] use of secondary notifications,[34] daily change of electrocardiographic electrodes or use of disposable electrocardiographic wires,[32, 33, 38] universal monitoring in high‐risk populations,[31] and timely discontinuation of monitoring in low‐risk populations.[38] Four intervention studies met our prespecified lower risk of bias criteria.[31, 32, 36, 38]

Proportion of Alarms Considered Actionable

Results of the observational studies are provided in Table 2. The proportion of alarms that were actionable was <1% to 26% in adult ICU settings,[9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 19] 20% to 36% in adult ward settings,[12, 15, 20] 17% in a mixed adult and pediatric PACU setting,[30] 3% to 13% in pediatric ICU settings,[22, 23, 24, 25, 26] and 1% in a pediatric ward setting.[22]

| Signals Included | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Author and Publication Year | Setting | Monitored Patient‐Hours | SpO2 | ECG Arrhythmia | ECG Parametersa | Blood Pressure | Total Alarms | Actionable Alarms | Alarm Response | Lower Risk of Bias |

| ||||||||||

| Adult | ||||||||||

| Atzema 2006[7] | ED | 371 | ✓ | 1,762 | 0.20% | |||||

| Billinghurst 2003[8] | CCU | 420 | ✓ | 751 | Not reported; 17% were valid | Nurses with higher acuity patients and smaller % of valid alarms had slower response rates | ||||

| Biot 2000[9] | ICU | 250 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3,665 | 3% | ||

| Chambrin 1999[10] | ICU | 1,971 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3,188 | 26% | ||

| Drew 2014[11] | ICU | 48,173 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,558,760 | 0.3% of 3,861 VT alarms | ✓ | |

| Gazarian 2014[12] | Ward | 54 nurse‐hours | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 205 | 22% | Response to 47% of alarms | ||

| Grges 2009[13] | ICU | 200 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1,214 | 5% | ||

| Gross 2011[15] | Ward | 530 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4,393 | 20% | ✓ | |

| Inokuchi 2013[14] | ICU | 2,697 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 11,591 | 6% | ✓ | |

| Koski 1990[16] | ICU | 400 | ✓ | ✓ | 2,322 | 12% | ||||

| Morales Snchez 2014[17] | ICU | 434 sessions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 215 | 25% | Response to 93% of alarms, of which 50% were within 10 seconds | ||

| Pergher 2014[18] | ICU | 60 | ✓ | 76 | Not reported | 72% of alarms stopped before nurse response or had >10 minutes response time | ||||

| Siebig 2010[19] | ICU | 982 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5,934 | 15% | ||

| Voepel‐Lewis 2013[20] | Ward | 1,616 | ✓ | 710 | 36% | Response time was longer for patients in highest quartile of total alarms | ||||

| Way 2014[21] | ED | 93 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 572 | Not reported; 75% were valid | Nurses responded to more alarms in resuscitation room vs acute care area, but response time was longer | |

| Pediatric | ||||||||||

| Bonafide 2015[22] | Ward + ICU | 210 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5,070 | 13% PICU, 1% ward | Incremental increases in response time as number of nonactionable alarms in preceding 120 minutes increased | ✓ |

| Lawless 1994[23] | ICU | 928 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,176 | 6% | |||

| Rosman 2013[24] | ICU | 8,232 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 54,656 | 4% of rhythm alarms true critical" | ||

| Talley 2011[25] | ICU | 1,470∥ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,245 | 3% | ||

| Tsien 1997[26] | ICU | 298 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,942 | 8% | |||

| van Pul 2015[27] | ICU | 113,880∥ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 222,751 | Not reported | Assigned nurse did not respond to 6% of alarms within 45 seconds | |

| Varpio 2012[28] | Ward | 49 unit‐hours | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 446 | Not reported | 70% of all alarms and 41% of crisis alarms were not responded to within 1 minute | |

| Both | ||||||||||

| O'Carroll 1986[29] | ICU | 2,258∥ | ✓ | 284 | 2% | |||||

| Wiklund 1994[30] | PACU | 207 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1,891 | 17% | |||

Relationship Between Alarm Exposure and Response Time

Whereas 9 studies addressed response time,[8, 12, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 27, 28] only 2 evaluated the relationship between alarm burden and nurse response time.[20, 22] Voepel‐Lewis and colleagues found that nurse responses were slower to patients with the highest quartile of alarms (57.6 seconds) compared to those with the lowest (45.4 seconds) or medium (42.3 seconds) quartiles of alarms on an adult ward (P = 0.046). They did not find an association between false alarm exposure and response time.[20] Bonafide and colleagues found incremental increases in response time as the number of nonactionable alarms in the preceding 120 minutes increased (P < 0.001 in the pediatric ICU, P = 0.009 on the pediatric ward).[22]

Interventions Effective in Reducing Alarms

Results of the 8 intervention studies are provided in Table 3. Three studies evaluated single interventions;[32, 33, 36] the remainder of the studies tested interventions with multiple components such that it was impossible to separate the effect of each component. Below, we have summarized study results, arranged by component. Because only 1 study focused on pediatric patients,[38] results from pediatric and adult settings are combined.

| First Author and Publication Year | Design | Setting | Main Intervention Components | Other/ Comments | Key Results | Results Statistically Significant? | Lower Risk of Bias | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widen Default Settings | Alarm Delays | Reconfigure Alarm Acuity | Secondary Notification | ECG Changes | |||||||

| |||||||||||