User login

Parsimonious blood use and lower transfusion triggers: What is the evidence?

For decades, physicians believed in the benefit of prompt transfusion of blood to keep the hemoglobin level at arbitrary, optimum levels, ie, close to normal values, especially in the critically ill, the elderly, and those with coronary syndromes, stroke, or renal failure.

However, the evidence supporting arbitrary hemoglobin values as an indication for transfusion was weak or nonexistent. Also, blood transfusion can have complications and adverse effects, and blood is costly and scarce. These considerations prompted research into when blood transfusion should be considered, and recommendations that it should be used more sparingly than in the past.

This review offers a perspective on the evidence supporting restrictive blood use. First, we focus on hemodilution studies that demonstrated that humans can tolerate anemia. Then, we look at studies that compared a restrictive transfusion strategy with a liberal one in patients with critical illness and active bleeding. We conclude with current recommendations for blood transfusion.

EVIDENCE FROM HEMODILUTION STUDIES

Hemoglobin is essential for tissue oxygenation, but the serum hemoglobin concentration is just one of several factors involved.1–5 In anemia, the body can adapt not only by increasing production of red blood cells, but also by:

- Increasing cardiac output

- Increasing synthesis of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG), with a consequent shift in the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve to the right, allowing enhanced release of oxygen at the tissue level

- Moving more carbon dioxide into the blood (the Bohr effect), which decreases pH and also shifts the dissociation curve to the right.

Just 20 years ago, physicians were using arbitrary cutoffs such as hemoglobin 10 g/dL or hematocrit 30% as indications for blood transfusion, without reasonable evidence to support these values. Not until acute normovolemic hemodilution studies were performed were we able to progressively appraise how well patients could tolerate lower levels of hemoglobin without significant adverse outcomes.

Acute normovolemic hemodilution involves withdrawing blood and replacing it with crystalloid or colloid solution to maintain the volume.6

Initial studies were done in animals and focused on the safety of acute anemia regarding splanchnic perfusion. Subsequently, studies proved that healthy, elderly, and stable cardiac patients can tolerate acute anemia with normal cardiovascular response. The targets in these studies were modest at first, but researchers aimed progressively for more aggressive hemodilution with lower hemoglobin targets and demonstrated that the body can tolerate and adapt to more severe anemia.6–8

Studies in healthy patients

Weiskopf et al9 assessed the effect of severe anemia in 32 conscious healthy patients (11 presurgical patients and 21 volunteers not undergoing surgery) by performing acute normovolemic hemodilution with 5% human albumin, autologous plasma, or both, with a target hemoglobin level of 5 g/dL. The process was done gradually, obtaining aliquots of blood of 500 to 900 mL. Cardiac index increased, along with a mild increase in oxygen consumption with no increase in plasma lactate levels, suggesting that in conscious healthy patients, tissue oxygenation remains adequate even in severe anemia.

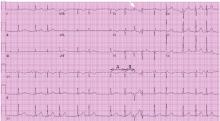

Leung et al10 addressed the electrocardiographic changes that occur with severe anemia (hemoglobin 5 g/dL) in 55 healthy volunteers. Three developed transient, reversible ST-segment depression, which was associated with a higher heart rate than in the volunteers with no electrocardiographic changes; however, the changes were reversible and asymptomatic, and thus were considered physiologic and benign.

Hemodilution in healthy elderly patients

Spahn et al11 performed 6 and 12 mL/kg isovolemic exchange of blood for 6% hydroxyethyl starch in 20 patients older than 65 years (mean age 76, range 65–88) without underlying coronary disease.

The patients’ mean hemoglobin level decreased from 11.6 g/dL to 8.8 g/dL. Their cardiac index and oxygen extraction values increased adequately, with stable oxygen consumption during hemodilution. There were no electrocardiographic signs of ischemia.

Hemodilution in coronary artery disease

Spahn et al12 performed hemodilution studies in 60 patients (ages 35–81) with coronary artery disease managed chronically with beta-blockers who were scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Hemodilution was performed with 6- and 12-mL/kg isovolemic exchange of blood for 6% hydroxyethyl starch maintaining normovolemia and stable filling pressures. Hemoglobin levels decreased from 12.6 g/dL to 9.9 g/dL. The hemodilution process was done before the revascularization. The authors monitored hemodynamic variables, ST-segment deviation, and oxygen consumption before and after each hemodilution.

There was a compensatory increase in cardiac index and oxygen extraction with consequent stable oxygen consumption. These changes were independent of patient age or left ventricular function. In addition, there were no electrocardiographic signs of ischemia.

Licker et al13 studied the hemodynamic effect of preoperative hemodilution in 50 patients with coronary artery disease undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery, performing transesophageal echocardiography before and after hemodilution. The patients underwent isovolemic exchange with iso-oncotic starch to target a hematocrit of 28%.

Acute normovolemic hemodilution triggered an increase in cardiac stroke volume, which had a direct correlation with an increase in the central venous pressure and the left ventricular end-diastolic area. No signs of ischemia were seen in these patients on electrocardiography or echocardiography (eg, left ventricular wall-motion abnormalities).

Hemodilution in mitral regurgitation

Spahn et al14 performed acute isovolemic hemodilution with 6% hydroxyethyl starch in 20 patients with mitral regurgitation. The cardiac filling pressures were stable before and after hemodilution; the mean hemoglobin value decreased from 13 to 10.3 g/dL. The cardiac index and oxygen extraction increased proportionally, with stable oxygen consumption; these findings were the same regardless of whether the patient was in normal sinus rhythm or atrial fibrillation.

Effect of hemodilution on cognition

Weiskopf et al15 assessed the effect of anemia on executive and memory function by inducing progressive acute isovolemic anemia in 90 healthy volunteers (age 29 ± 5), reducing their hemoglobin values to 7, 6, and 5 g/dL and performing repetitive neuropsychological and memory testing before and after the hemodilution, as well as after autologous blood transfusion to return their hemoglobin level to 7 g/dL.

There were no changes in reaction time or error rate at a hemoglobin concentration of 7 g/dL compared with the performance at a baseline hemoglobin concentration of 14 g/dL. The volunteers got slower on a mathematics test at hemoglobin levels of 6 g/dL and 5 g/dL, but their error rate did not increase. Immediate and delayed memory were significantly impaired at hemoglobin of 5 g/dL but not at 6 g/dL. All tests normalized with blood transfusion once the hemoglobin level reached 7 g/dL.15

Weiskopf et al16 subsequently investigated whether giving supplemental oxygen to raise the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (Pao2) to 350 mm Hg or greater would overcome the neurocognitive effects of severe acute anemia. They followed a protocol similar to the one in the earlier study15 and induced anemia in 31 healthy volunteers, age 28 ± 4 years, with a mean baseline hemoglobin concentration of 12.7 g/dL.

When the volunteers reached a hemoglobin concentration of 5.7 ± 0.3 g/dL, they were significantly slower on the mathematics test, and their delayed memory was significantly impaired. Then, in a double-blind fashion, they were given either room air or oxygen. Oxygen increased the Pao2 to 406 mm Hg and normalized neurocognitive performance.

Hemodilution studies in surgical patients

A 2015 meta-analysis17 of 63 studies involving 3,819 surgical patients compared the risk of perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion as well as the overall volume of transfused blood in patients undergoing preoperative acute normovolemic hemodilution vs a control group. Though the overall data showed that the patients who underwent acute normovolemic hemodilution needed fewer transfusions and less blood (relative risk [RR] 0.74, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.63–0.88, P = .0006), the authors noted significant heterogeneity and publication bias.

However, the hemodilution studies paved the way for justifying a more conservative and restrictive transfusion strategy, with a hemoglobin cutoff value of 7 g/dL, and in acute anemia, using oxygen to overcome acute neurocognitive effects while searching for and correcting the cause of the anemia.

STUDIES OF RESTRICTIVE VS LIBERAL TRANSFUSION STRATEGIES

Studies in critical care and high-risk patients

Hébert et al18 randomized 418 critical care patients to a restrictive transfusion approach (in which they were given red blood cells if their hemoglobin concentration dropped below 7.0 g/dL) and 420 patients to a liberal strategy (given red blood cells if their hemoglobin concentration dropped below 10.0 g/dL). Mortality rates (restrictive vs liberal strategy) were as follows:

- Overall at 30 days 18.7% vs 23.3%, P = .11

- In the subgroup with less-severe disease (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II [APACHE II] score < 20), 8.7% vs 16.1%, P = .03

- In the subgroup under age 55, 5.7% vs 13%, P = .02

- In the subgroup with clinically significant cardiac disease, 20.5% vs 22.9%, P = .69

- In the hospital, 22.2% vs 28.1%; P = .05.

This study demonstrated that parsimonious blood use did not worsen clinical outcomes in critical care patients.

Carson et al19 evaluated 2,016 patients age 50 and older who had a history of or risk factors for cardiovascular disease and a baseline hemoglobin level below 10 g/dL who underwent surgery for hip fracture. Patients were randomized to two transfusion strategies based on threshold hemoglobin level: restrictive (< 8 g/dL) or liberal (< 10 g/dL). The primary outcome was death or inability to walk without assistance at 60-day follow-up. The median number of units of blood used was 2 in the liberal group and 0 in the restrictive group.

There was no significant difference in the rates of the primary outcome (odds ratio [OR] 1.01, 95% CI 0.84–1.22), infection, venous thromboembolism, or reoperation. This study demonstrated that a liberal transfusion strategy offered no benefit over a restrictive one.

Rao et al20 analyzed the impact of blood transfusion in 24,112 patients with acute coronary syndromes enrolled in three large trials. Ten percent of the patients received at least 1 blood transfusion during their hospitalization, and they were older and had more complex comorbidity.

At 30 days, the group that had received blood had higher rates of death (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 3.94, 95% CI 3.26–4.75) and the combined outcome of death or myocardial infarction (HR 2.92, 95% CI 2.55–3.35). Transfusion in patients whose nadir hematocrit was higher than 25% was associated with worse outcomes.

This study suggests being cautious about routinely transfusing blood in stable patients with ischemic heart disease solely on the basis of arbitrary hematocrit levels.

Carson et al,21 however, in a later trial, found a trend toward worse outcomes with a restrictive strategy than with a liberal one. Here, 110 patients with acute coronary syndrome or stable angina undergoing cardiac catheterization were randomized to a target hemoglobin level of either at least 8 mg/dL or at least 10 g/dL. The primary outcome (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or unscheduled revascularization 30 days after randomization) occurred in 14 patients (25.5%) in the restrictive group and 6 patients (10.9%) in the liberal group (P = .054), and 7 (13.0%) vs 1 (1.8%) of the patients died (P = .032).

Murphy et al22 similarly found trends toward worse outcomes with a restrictive strategy in cardiac patients. The investigators randomized 2,007 elective cardiac surgery patients with a postoperative hemoglobin level lower than 9 g/dL to a hemoglobin transfusion threshold of either 7.5 or 9 g/dL. Outcomes (restrictive vs liberal strategies):

- Transfusion rates 53.4% vs 92.2%

- Rates of the primary outcome (a serious infection [sepsis or wound infection] or ischemic event [stroke, myocardial infarction, mesenteric ischemia, or acute kidney injury] within 3 months):

35.1% vs 33.0%, OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.91–1.34, P = .30) - Mortality rates 4.2% vs 2.6%, HR 1.64, 95% CI 1.00–2.67, P = .045

- Total costs did not differ significantly between the groups.

These studies21,22 suggest the need for more definitive trials in patients with active coronary disease and in cardiac surgery patients.

Holst et al23 randomized 998 intensive care patients in septic shock to hemoglobin thresholds for transfusion of 7 vs 9 g/dL. Mortality rates at 90 days (the primary outcome) were 43.0% vs 45.0%, RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.78–1.09, P = .44.

This study suggests that even in septic shock, a liberal transfusion strategy has no advantage over a parsimonious one.

Active bleeding, especially active gastrointestinal bleeding, poses a significant stress that may trigger empirical transfusion even without evidence of the real hemoglobin level.

Villanueva et al24 randomized 921 patients with severe acute upper-gastrointestinal bleeding to two groups, with hemoglobin transfusion triggers of 7 vs 9 g/dL. The findings were impressive:

- Freedom from transfusion 51% vs 14% (P < .001)

- Survival rates at 6 weeks 95% vs 91% (HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.33–0.92, P = .02)

- Rebleeding 10% vs 16% (P = .01).

Patients with peptic ulcer disease as well as those with cirrhosis stage Child-Pugh class A or B had higher survival rates with a restrictive transfusion strategy.

The RELIEVE trial25 compared the effect of a restrictive transfusion strategy in elderly patients on mechanical ventilation in 6 intensive care units in the United Kingdom. Transfusion triggers were hemoglobin 7 vs 9 g/dL, and the mortality rate at 180 days was 55% vs 37%, RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.44–1.05, P = .073.

Meta-analyses and observational studies

Rohde et al26 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 trials with 7,456 patients, which revealed that a restrictive strategy is associated with a lower risk of nosocomial infection, including pneumonia, wound infection, and sepsis.

The pooled risk of all serious infections was 10.6% in the restrictive group and 12.7% in the liberal group. Even after adjusting for the use of leukocyte reduction, the risk of infection was lower in the restrictive strategy group (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.69–0.99). With a hemoglobin threshold of less than 7.0 g/dL, the risk of serious infection was 14% lower. Although this was not statistically significant overall (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.72–1.02), the difference was statistically significant in the subgroup undergoing orthopedic surgery (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.53–0.97) and the subgroup presenting with sepsis (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.28–0.95).

Salpeter et al27 performed a meta-analysis and systematic review of three randomized trials (N = 2,364) comparing a restrictive hemoglobin transfusion trigger (hemoglobin < 7 g/dL) vs a more liberal trigger. The groups with restrictive transfusion triggers had lower rates of:

- In-hospital mortality (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60–0.92)

- Total mortality (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.65–0.98)

- Rebleeding (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45–0.90)

- Acute coronary syndrome (RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.22–0.89)

- Pulmonary edema (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.33–0.72)

- Bacterial infections (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73–1.00).

Wang et al28 performed a meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials in patients with upper-gastrointestinal bleeding comparing restrictive (hemoglobin < 7 g/dL) vs liberal transfusion strategies. The primary outcomes were death and rebleeding. The restrictive strategy was associated with:

- A lower mortality rate (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31–0.87, P = .01)

- A lower rebleeding rate (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.03–2.10, P = .21)

- Shorter hospitalizations (P = .009)

- Less blood transfused (P = .0005).

Vincent et al,29 in a prospective observational study of 3,534 patients in intensive care units in 146 facilities in Western Europe, found a correlation between transfusion and mortality. Transfusion was done most often in elderly patients and those with a longer stay in the intensive care unit. The 28-day mortality rate was 22.7% in patients who received a transfusion and 17.1% in those who did not (P = .02). The more units of blood the patients received, the more likely they were to die, and receiving more than 4 units was associated with worse outcomes (P = .01).

Dunne et al30 performed a study of 6,301 noncardiac surgical patients in the Veterans Affairs Maryland Healthcare System from the National Veterans Administration Surgical Quality Improvement Program from 1995 to 2000. Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that the composite of low hematocrit before and after surgery and high transfusion rates (> 4 units per hospitalization) were associated with higher rates of death (P < .01) and postoperative pneumonia (P ≤ .05) and longer hospitalizations (P < .05). The risk of pneumonia increased proportionally with the decrease in hematocrit.

These findings support pharmacologic optimization of anemia with hematinic supplementation before surgery to decrease the risk of needing a transfusion, often with parenteral iron. The fact that the patient’s hemoglobin can be optimized preoperatively by nontransfusional means may decrease the likelihood of blood transfusion, as the hemoglobin will potentially remain above the transfusion threshold. For example, if a patient has a preoperative hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL, and it is optimized up to 12, then if postoperatively the hemoglobin level drops 3 g/dL instead of reaching the threshold of 7 g/dL, the nadir will be just 9 g/dL, far above that transfusion threshold.

Brunskill et al,31 in a Cochrane review of 6 trials with 2,722 patients undergoing surgery for hip fracture, found no difference in rates of mortality, functional recovery or postoperative morbidity with a restrictive transfusion strategy (hemoglobin target > 8 g/dL vs a liberal one (> 10 g/dL). However, the quality of evidence was rated as low. The authors concluded that there is no justification for liberal red blood cell transfusion thresholds (10 g/dL), and a more restrictive transfusion threshold is preferable.

Weinberg et al32 found that, in trauma patients, receiving more than 6 units of blood was associated with poor prognosis, and outcomes were worse when the blood was older than 2 weeks. However, the effect of blood age is not significant when using smaller transfusion volumes (1 to 2 units of red blood cells).

Studies in sickle cell disease

Sickle cell disease patients have high levels of hemoglobin S, which causes erythrocyte sickling and increases blood viscosity. Transfusion with normal erythrocytes increases the amount of hemoglobin A (the normal variant).33,34

In trials in surgical patients,35,36 conservative strategies for preoperative blood transfusion aiming at a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL were as effective in preventing postoperative complications as decreasing the hemoglobin S levels to 30% by aggressive exchange transfusion.35

In nonsurgical patients, blood transfusion should be based on formal risk-benefit assessments. Therefore, the expert panel report on sickle cell management advises against blood transfusion in sickle cell patients with uncomplicated vaso-occlusive crises, priapism, asymptomatic anemia, or acute kidney injury in the absence of multisystem organ failure.34

Is hemoglobin the most relevant marker?

Most studies that compared restrictive and liberal transfusion strategies focused on using a lower hemoglobin threshold as the transfusion trigger, not on using fewer units of blood. Is the amount of blood transfused more important than the hemoglobin threshold? Perhaps a study focused both on a restrictive vs liberal strategy and also on the minimum amount of blood that each patient may benefit from would help to answer this question.

We should beware of routinely using the hemoglobin concentration as a threshold for transfusion and a surrogate marker of transfusion benefit because changes in hemoglobin concentration may not reflect changes in absolute red cell mass.37 Changes in plasma volume (an increase or decrease) affect the hematocrit concentration without necessarily affecting the total red cell mass. Unfortunately, red cell mass is very difficult to measure; hence, the hemoglobin and hematocrit values are used instead. Studies addressing changes in red cell mass may be needed, perhaps even to validate using the hemoglobin concentration as the sole indicator for transfusion.

Is fresh blood better than old blood?

Using blood that is more than 14 days old may be associated with poor outcomes, for several possible reasons. Red blood cells age rapidly in refrigeration, and usually just 75% may remain viable 24 hours after phlebotomy. Adenosine triphosphate and 2,3-DPG levels steadily decrease, with a consequent decrease in capacity for appropriate tissue oxygen delivery. In addition, loss of membrane phospholipids causes progressive rigidity of the red cell membrane with consequent formation of echynocytes after 14 to 21 days.38,39

The use of blood more than 14 days old in cardiac surgery patients has been associated with worse outcomes, including higher rates of death, prolonged intubation, acute renal failure, and sepsis.40 Similar poor outcomes have been seen in trauma patients.32

Lacroix et al,41 in a multicenter, randomized trial in critically ill adults, compared the outcomes of transfusion of fresh packed red cells (stored < 8 days) or old blood (stored for a mean of 22 days). The primary outcome was the mortality rate at 90 days: 37.0% in the fresh-blood group vs 35.3% in the old-blood group (HR 1.1, 95% CI 0.9–1.2, P = .38).

The authors concluded that using fresh blood compared with old blood was not associated with a lower 90-day mortality rate in critically ill adults.

RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH TRANSFUSION

Infections

The risk of infection from blood transfusion is small. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is transmitted in 1 in 1.5 million transfused blood components, and hepatitis C virus in 1 in 1.1 million; these odds are similar to those of having a fatal airplane accident (1 in 1.7 million per flight). Hepatitis B virus infection is more common, the reported incidence being 1 in 357,000.42

Noninfectious complications

Transfusion-associated circulatory overload occurs in 4% to 6% of patients who receive a transfusion. Therefore, circulatory overload is a greater danger from transfusion than infection is.42

Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions occur in 1.1% of patients with prestorage leukoreduction.

Transfusion-associated acute lung injury occurs in 0.8 per 10,000 blood components transfused.

Errors associated with blood transfusion include, in decreasing order of frequency, transfusion of the wrong blood component, handling and storage errors, inappropriate administration of anti-D immunoglobulin, and avoidable, delayed, or insufficient transfusions.43

Surgery and condition-specific complications of red blood cell transfusion

Cardiovascular surgery. Transfusion is associated with a higher risk of postoperative stroke, respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, prolonged intubation time, reintubation, in-hospital death, sepsis, and longer postoperative length of stay.44

Malignancy. The use of blood in this setting has been found to be an independent predictor of recurrence, decreased survival, and increased risk of lymphoplasmacytic and marginal-zone lymphomas.44–47

Vascular, orthopedic, and other surgeries. Transfusion is associated with a higher risk of death, thromboembolic events, acute kidney injury, death, composite morbidity, reoperation, sepsis, and pulmonary complications.44

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, sepsis, and intensive care unit admissions. Transfusion is associated with an increased risk of rebleeding, death, and secondary infections.44

COST OF RED BLOOD CELL TRANSFUSION

Up to 85 million units of red blood cells are transfused per year worldwide, 15 million of them in the United States.42 At our hospital in 2013, 1 unit of leukocyte-reduced red blood cells cost $957.27, which included the costs of acquisition, processing, banking, patient testing, administration, and monitoring.

The Premier Healthcare Alliance48 analyzed data from 7.4 million discharges from 464 hospitals between April 2011 and March 2012. Blood use varied significantly among hospitals, and the hospitals in the lowest quartile of blood use had better patient outcomes. If all the hospitals used as little blood as those in the lowest quartile and had outcomes as good, blood product use would be reduced by 802,716 units, with savings of up to $165 million annually.

In addition to the economic cost of blood transfusion, the clinician must be aware of the cost in terms of comorbidities caused by unnecessary blood transfusion.49,50

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE AABB

In view of all the current compelling evidence, a restrictive approach to transfusion is the single best strategy to minimize adverse outcomes.51 Below, we outline the current recommendations from the AABB (formerly the American Association of Blood Banks),42 which are similar to the national clinical guideline on blood transfusion in the United Kingdom,52 and have recently been updated, confirming the initial recommendations.53

In critical care patients, transfusion should be considered if the hemoglobin concentration is 7 g/dL or less.

In postoperative patients and hospitalized patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease, transfusion should be considered if the hemoglobin concentration is 8 g/dL or less or if the patient has signs or symptoms of anemia such as chest pain, orthostatic hypotension, or tachycardia unresponsive to fluid resuscitation, or heart failure.

In hemodynamically stable patients with acute coronary syndrome, there is not enough evidence to allow a formal recommendation for or against a liberal or restrictive transfusion threshold.

Consider both the hemoglobin concentration and the symptoms when deciding whether to give a transfusion. This recommendation is shared by a National Institutes of Health consensus conference,54 which indicates that multiple factors related to the patient’s clinical status and oxygen delivery should be considered before deciding to transfuse red blood cells.

The Society of Hospital Medicine55 and the American Society of Hematology56 concur with a parsimonious approach to blood use in their Choosing Wisely campaigns. The American Society of Hematology recommends that if transfusion of red blood cells is necessary, the minimum number of units should be given that relieve the symptoms of anemia or achieve a safe hemoglobin range (7–8 g/dL in stable noncardiac inpatients).57

New electronic tools can monitor the ordering and use of blood products in real time and can identify the hemoglobin level used as the trigger for transfusion. They also provide data on blood use by physician, hospital, and department. These tools can reveal current practice at a glance and allow sharing of best practices among peers and institutions.52

CONSIDER TRANSFUSION FOR HEMOGLOBIN BELOW 7 G/DL

The routine use of blood has come under scrutiny, given its association with increased healthcare costs and morbidity. The accepted practice in stable medical patients is a restrictive threshold approach for blood transfusion, which is to consider (not necessarily give) a single unit of packed red blood cells for a hemoglobin less than 7 g/dL.

However, studies in acute coronary syndrome patients and postoperative cardiac surgery patients have not shown the restrictive threshold to be superior to a liberal threshold in terms of outcomes and costs. This variability suggests the need for further studies to determine the best course of action in different patient subpopulations (eg, surgical, oncologic, trauma, critical illness).

Also, a limitation of most of the clinical studies was that only the hemoglobin concentration was used as a marker of anemia, with no strict assessment of changes in red cell mass with transfusion.

Despite the variability in certain populations, the overall weight of current evidence favors a restrictive approach to blood transfusion (hemoglobin < 7 g/dL), although perhaps in patients who have active coronary disease or are undergoing cardiac surgery, a more lenient threshold (< 8 g/dL) for transfusion should be considered.

- Shander A, Gross I, Hill S, Javidroozi M, Sledge S; College of American Pathologists; American Society of Anesthesiologists; Society of Thoracic Surgeons and Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists; Society of Critical Care Medicine; Italian Society of Transfusion Medicine and Immunohaematology; American Association of Blood Banks. A new perspective on best transfusion practices. Blood Transfus 2013; 11:193–202.

- Madjdpour C, Spahn DR. Allogeneic red blood cell transfusion: physiology of oxygen transport. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2007; 21:163–171.

- Tánczos K, Molnár Z. The oxygen supply-demand balance: a monitoring challenge. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2013; 27:201–207.

- Hebert PC, Van der Linden P, Biro G, Hu LQ. Physiologic aspects of anemia. Crit Care Clin 2004; 20:187–212.

- Spinelli E, Bartlett RH. Anemia and transfusion in critical care: physiology and management. J Intensive Care Med 2016; 31:295–306.

- Jamnicki M, Kocian R, Van Der Linden P, Zaugg M, Spahn DR. Acute normovolemic hemodilution: physiology, limitations, and clinical use. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2003; 17:747–754.

- Monk TG. Acute normovolemic hemodilution. Anesthesiol Clin North America 2005; 23:271–281.

- Shander A, Rijhwani TS. Acute normovolemic hemodilution. Transfusion 2004; 44(suppl 2):26S–34S.

- Weiskopf RB, Viele MK, Feiner J, et al. Human cardiovascular and metabolic response to acute, severe isovolemic anemia. JAMA 1998; 279:217–221.

- Leung JM, Weiskopf RB, Feiner J, et al. Electrocardiographic ST-segment changes during acute, severe isovolemic hemodilution in humans. Anesthesiology 2000; 93:1004–1010.

- Spahn DR, Zollinger A, Schlumpf RB, et al. Hemodilution tolerance in elderly patients without known cardiac disease. Anesth Analg 1996; 82:681–686.

- Spahn DR, Schmid ER, Seifert B, Pasch T. Hemodilution tolerance in patients with coronary artery disease who are receiving chronic beta-adrenergic blocker therapy. Anesth Analg 1996; 82:687–694.

- Licker M, Ellenberger C, Sierra J, Christenson J, Diaper J, Morel D. Cardiovascular response to acute normovolemic hemodilution in patients with coronary artery diseases: assessment with transesophageal echocardiography. Crit Care Med 2005; 33:591–597.

- Spahn DR, Seifert B, Pasch T, Schmid ER. Haemodilution tolerance in patients with mitral regurgitation. Anaesthesia 1998; 53:20–24.

- Weiskopf RB, Kramer JH, Viele M, et al. Acute severe isovolemic anemia impairs cognitive function and memory in humans. Anesthesiology 2000; 92:1646–1652.

- Weiskopf RB, Feiner J, Hopf HW, et al. Oxygen reverses deficits of cognitive function and memory and increased heart rate induced by acute severe isovolemic anemia. Anesthesiology 2002; 96:871–877.

- Zhou X, Zhang C, Wang Y, Yu L, Yan M. Preoperative acute normovolemic hemodilution for minimizing allogeneic blood transfusion: a meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 2015; 121:1443–1455.

- Hébert P, Wells G, Blajchman M, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med 1999: 340:409–417.

- Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al; FOCUS Investigators. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:2453–2462.

- Rao SV, Jollis JG, Harrington RA, et al. Relationship of blood transfusion and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2004; 292:1555–1562.

- Carson JL, Brooks MM, Abbott JD, et al. Liberal versus restrictive transfusion thresholds for patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2013; 165:964.e1–971.e1.

- Murphy GJ, Pike K, Rogers CA, et al; TITRe2 Investigators. Liberal or restrictive transfusion after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:997–1008.

- Holst LB, Haase N, Wetterslev J, et al; TRISS Trial Group; Scandinavian Critical Care Trials Group. Lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in septic shock. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1381–1391.

- Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:11–21.

- Walsh TS, Boyd JA, Watson D, et al; RELIEVE Investigators. Restrictive versus liberal transfusion strategies for older mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a randomized pilot trial. Crit Care Med 2013; 41:2354–2363.

- Rohde JM, Dimcheff DE, Blumberg N, et al. Health care–associated infection after red blood cell transfusion. JAMA 2014; 311:1317–1326.

- Salpeter SR, Buckley JS, Chatterjee S. Impact of more restrictive blood transfusion strategies on clinical outcomes: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Med 2014; 127:124.e3–131.e3.

- Wang J, Bao YX, Bai M, Zhang YG, Xu WD, Qi XS. Restrictive vs liberal transfusion for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19:6919–6927.

- Vincent JL, Baron JF, Reinhart K, et al; ABC (Anemia and Blood Transfusion in Critical Care) Investigators. Anemia and blood transfusion in critically ill patients. JAMA 2002; 288:1499–1507.

- Dunne JR, Malone D, Tracy JK, Gannon C, Napolitano LM. Perioperative anemia: an independent risk factor for infection, mortality, and resource utilization in surgery. J Surg Res 2002; 102:237–244.

- Brunskill SJ, Millette SL, Shokoohi A, et al. Red blood cell transfusion for people undergoing hip fracture surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 4:CD009699.

- Weinberg JA, McGwin G Jr, Griffin RL, et al. Age of transfused blood: an independent predictor of mortality despite universal leukoreduction. J Trauma 2008; 65:279–284.

- Steinberg M. Management of sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:1021–1030.

- Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN, et al. Management of sickle cell disease. JAMA 2014; 312:1033–1048.

- Vichinsky EP, Haberkern CM, Neumayr L, et al. A comparison of conservative and aggressive transfusion regimens in the perioperative management of sickle cell disease. The Preoperative Transfusion in Sickle Cell Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:206–213.

- Howard J, Malfroy M, Llewelyn C, et al. The Transfusion Alternatives Preoperatively in Sickle Cell Disease (TAPS) study: a randomised, controlled, multicentre clinical trial. Lancet 2013; 381:930–938.

- Goodnough LT, Levy JH, Murphy MF. Concepts of blood transfusion in adults. Lancet 2013; 381:1845–1854.

- Holme S. Current issues related to the quality of stored RBCs. Transfus Apher Sci 2005; 33:55–61.

- Hovav T, Yedgar S, Manny N, Barshtein G. Alteration of red cell aggregability and shape during blood storage. Transfusion 1999; 39:277–281.

- Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:1229–1239.

- Lacroix J, Hebert PC, Fergusson DA, et al. Age of transfused blood in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:1410–1418.

- Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, et al; Clinical Transfusion Medicine Committee of the AABB. Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:49–58.

- Bolton-Maggs P, Watt A, Poles D, et al, on behalf of the Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT) Steering Group. The 2015 Annual SHOT Report. www.shotuk.org/wp-content/uploads/SHOT-2015-Annual-Report-Web-Edition-Final-bookmarked.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2016.

- Shander A, Javidroozi M, Ozawa S, Hare GMT. What is really dangerous: anaemia or transfusion? Br J Anaesth 2011; 107(suppl 1):i41–i59.

- Reeh M, Ghadban T, Dedow J, et al. Allogenic blood transfusion is associated with poor perioperative and long-term outcome in esophageal cancer. World J Surg 2016 Oct 11. [Epub ahead of print]

- Elmi M, Mahar A, Kagedan D, et al. The impact of blood transfusion on perioperative outcomes following gastric cancer resection: an analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Can J Surg 2016; 59:322–329.

- Aquina CT, Blumberg N, Becerra AZ, et al. Association among blood transfusion, sepsis, and decreased long-term survival after colon cancer resection. Ann Surg 2016; Sep 14. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 27631770.

- Premiere Analysis. Standardization of blood utilization practices could provide opportunity for improved outcomes, reduced costs. A Premiere Healthcare Alliance Analysis. 2012.

- Simeone F, Franchi F, Cevenini G, et al. A simple clinical model for planning transfusion quantities in heart surgery. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2011; 11:44.

- Spahn DR, Goodnough LT. Alternatives to blood transfusion. Lancet 2013; 381:1855–1865.

- Holst LB, Petersen MW, Haase N, Perner A, Wetterslev J. Restrictive versus liberal transfusion strategy for red blood cell transfusion: systematic review of randomised trials with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMJ 2015; 350:h1354.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11822/.

- Carson JL, Guyatt G, Heddle NM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines from the AABB: red blood cell transfusion thresholds and storage. JAMA 2016 Oct 12. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9185. [Epub ahead of print]

- Consensus conference. Perioperative red blood cell transfusion. JAMA 1988; 260:2700–2703.

- Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med 2013; 8:486–492.

- Hicks LK, Bering H, Carson KR, et al. The ASH Choosing Wisely® campaign: five hematologic tests and treatments to question. Blood 2013; 122:3879–3883.

- Haemonetics IMPACT Online. The Blood Management Company. www.haemonetics.com/Products/Services/Consulting Services/IMPACT Online.aspx. Accessed November 30, 2016.

For decades, physicians believed in the benefit of prompt transfusion of blood to keep the hemoglobin level at arbitrary, optimum levels, ie, close to normal values, especially in the critically ill, the elderly, and those with coronary syndromes, stroke, or renal failure.

However, the evidence supporting arbitrary hemoglobin values as an indication for transfusion was weak or nonexistent. Also, blood transfusion can have complications and adverse effects, and blood is costly and scarce. These considerations prompted research into when blood transfusion should be considered, and recommendations that it should be used more sparingly than in the past.

This review offers a perspective on the evidence supporting restrictive blood use. First, we focus on hemodilution studies that demonstrated that humans can tolerate anemia. Then, we look at studies that compared a restrictive transfusion strategy with a liberal one in patients with critical illness and active bleeding. We conclude with current recommendations for blood transfusion.

EVIDENCE FROM HEMODILUTION STUDIES

Hemoglobin is essential for tissue oxygenation, but the serum hemoglobin concentration is just one of several factors involved.1–5 In anemia, the body can adapt not only by increasing production of red blood cells, but also by:

- Increasing cardiac output

- Increasing synthesis of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG), with a consequent shift in the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve to the right, allowing enhanced release of oxygen at the tissue level

- Moving more carbon dioxide into the blood (the Bohr effect), which decreases pH and also shifts the dissociation curve to the right.

Just 20 years ago, physicians were using arbitrary cutoffs such as hemoglobin 10 g/dL or hematocrit 30% as indications for blood transfusion, without reasonable evidence to support these values. Not until acute normovolemic hemodilution studies were performed were we able to progressively appraise how well patients could tolerate lower levels of hemoglobin without significant adverse outcomes.

Acute normovolemic hemodilution involves withdrawing blood and replacing it with crystalloid or colloid solution to maintain the volume.6

Initial studies were done in animals and focused on the safety of acute anemia regarding splanchnic perfusion. Subsequently, studies proved that healthy, elderly, and stable cardiac patients can tolerate acute anemia with normal cardiovascular response. The targets in these studies were modest at first, but researchers aimed progressively for more aggressive hemodilution with lower hemoglobin targets and demonstrated that the body can tolerate and adapt to more severe anemia.6–8

Studies in healthy patients

Weiskopf et al9 assessed the effect of severe anemia in 32 conscious healthy patients (11 presurgical patients and 21 volunteers not undergoing surgery) by performing acute normovolemic hemodilution with 5% human albumin, autologous plasma, or both, with a target hemoglobin level of 5 g/dL. The process was done gradually, obtaining aliquots of blood of 500 to 900 mL. Cardiac index increased, along with a mild increase in oxygen consumption with no increase in plasma lactate levels, suggesting that in conscious healthy patients, tissue oxygenation remains adequate even in severe anemia.

Leung et al10 addressed the electrocardiographic changes that occur with severe anemia (hemoglobin 5 g/dL) in 55 healthy volunteers. Three developed transient, reversible ST-segment depression, which was associated with a higher heart rate than in the volunteers with no electrocardiographic changes; however, the changes were reversible and asymptomatic, and thus were considered physiologic and benign.

Hemodilution in healthy elderly patients

Spahn et al11 performed 6 and 12 mL/kg isovolemic exchange of blood for 6% hydroxyethyl starch in 20 patients older than 65 years (mean age 76, range 65–88) without underlying coronary disease.

The patients’ mean hemoglobin level decreased from 11.6 g/dL to 8.8 g/dL. Their cardiac index and oxygen extraction values increased adequately, with stable oxygen consumption during hemodilution. There were no electrocardiographic signs of ischemia.

Hemodilution in coronary artery disease

Spahn et al12 performed hemodilution studies in 60 patients (ages 35–81) with coronary artery disease managed chronically with beta-blockers who were scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Hemodilution was performed with 6- and 12-mL/kg isovolemic exchange of blood for 6% hydroxyethyl starch maintaining normovolemia and stable filling pressures. Hemoglobin levels decreased from 12.6 g/dL to 9.9 g/dL. The hemodilution process was done before the revascularization. The authors monitored hemodynamic variables, ST-segment deviation, and oxygen consumption before and after each hemodilution.

There was a compensatory increase in cardiac index and oxygen extraction with consequent stable oxygen consumption. These changes were independent of patient age or left ventricular function. In addition, there were no electrocardiographic signs of ischemia.

Licker et al13 studied the hemodynamic effect of preoperative hemodilution in 50 patients with coronary artery disease undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery, performing transesophageal echocardiography before and after hemodilution. The patients underwent isovolemic exchange with iso-oncotic starch to target a hematocrit of 28%.

Acute normovolemic hemodilution triggered an increase in cardiac stroke volume, which had a direct correlation with an increase in the central venous pressure and the left ventricular end-diastolic area. No signs of ischemia were seen in these patients on electrocardiography or echocardiography (eg, left ventricular wall-motion abnormalities).

Hemodilution in mitral regurgitation

Spahn et al14 performed acute isovolemic hemodilution with 6% hydroxyethyl starch in 20 patients with mitral regurgitation. The cardiac filling pressures were stable before and after hemodilution; the mean hemoglobin value decreased from 13 to 10.3 g/dL. The cardiac index and oxygen extraction increased proportionally, with stable oxygen consumption; these findings were the same regardless of whether the patient was in normal sinus rhythm or atrial fibrillation.

Effect of hemodilution on cognition

Weiskopf et al15 assessed the effect of anemia on executive and memory function by inducing progressive acute isovolemic anemia in 90 healthy volunteers (age 29 ± 5), reducing their hemoglobin values to 7, 6, and 5 g/dL and performing repetitive neuropsychological and memory testing before and after the hemodilution, as well as after autologous blood transfusion to return their hemoglobin level to 7 g/dL.

There were no changes in reaction time or error rate at a hemoglobin concentration of 7 g/dL compared with the performance at a baseline hemoglobin concentration of 14 g/dL. The volunteers got slower on a mathematics test at hemoglobin levels of 6 g/dL and 5 g/dL, but their error rate did not increase. Immediate and delayed memory were significantly impaired at hemoglobin of 5 g/dL but not at 6 g/dL. All tests normalized with blood transfusion once the hemoglobin level reached 7 g/dL.15

Weiskopf et al16 subsequently investigated whether giving supplemental oxygen to raise the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (Pao2) to 350 mm Hg or greater would overcome the neurocognitive effects of severe acute anemia. They followed a protocol similar to the one in the earlier study15 and induced anemia in 31 healthy volunteers, age 28 ± 4 years, with a mean baseline hemoglobin concentration of 12.7 g/dL.

When the volunteers reached a hemoglobin concentration of 5.7 ± 0.3 g/dL, they were significantly slower on the mathematics test, and their delayed memory was significantly impaired. Then, in a double-blind fashion, they were given either room air or oxygen. Oxygen increased the Pao2 to 406 mm Hg and normalized neurocognitive performance.

Hemodilution studies in surgical patients

A 2015 meta-analysis17 of 63 studies involving 3,819 surgical patients compared the risk of perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion as well as the overall volume of transfused blood in patients undergoing preoperative acute normovolemic hemodilution vs a control group. Though the overall data showed that the patients who underwent acute normovolemic hemodilution needed fewer transfusions and less blood (relative risk [RR] 0.74, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.63–0.88, P = .0006), the authors noted significant heterogeneity and publication bias.

However, the hemodilution studies paved the way for justifying a more conservative and restrictive transfusion strategy, with a hemoglobin cutoff value of 7 g/dL, and in acute anemia, using oxygen to overcome acute neurocognitive effects while searching for and correcting the cause of the anemia.

STUDIES OF RESTRICTIVE VS LIBERAL TRANSFUSION STRATEGIES

Studies in critical care and high-risk patients

Hébert et al18 randomized 418 critical care patients to a restrictive transfusion approach (in which they were given red blood cells if their hemoglobin concentration dropped below 7.0 g/dL) and 420 patients to a liberal strategy (given red blood cells if their hemoglobin concentration dropped below 10.0 g/dL). Mortality rates (restrictive vs liberal strategy) were as follows:

- Overall at 30 days 18.7% vs 23.3%, P = .11

- In the subgroup with less-severe disease (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II [APACHE II] score < 20), 8.7% vs 16.1%, P = .03

- In the subgroup under age 55, 5.7% vs 13%, P = .02

- In the subgroup with clinically significant cardiac disease, 20.5% vs 22.9%, P = .69

- In the hospital, 22.2% vs 28.1%; P = .05.

This study demonstrated that parsimonious blood use did not worsen clinical outcomes in critical care patients.

Carson et al19 evaluated 2,016 patients age 50 and older who had a history of or risk factors for cardiovascular disease and a baseline hemoglobin level below 10 g/dL who underwent surgery for hip fracture. Patients were randomized to two transfusion strategies based on threshold hemoglobin level: restrictive (< 8 g/dL) or liberal (< 10 g/dL). The primary outcome was death or inability to walk without assistance at 60-day follow-up. The median number of units of blood used was 2 in the liberal group and 0 in the restrictive group.

There was no significant difference in the rates of the primary outcome (odds ratio [OR] 1.01, 95% CI 0.84–1.22), infection, venous thromboembolism, or reoperation. This study demonstrated that a liberal transfusion strategy offered no benefit over a restrictive one.

Rao et al20 analyzed the impact of blood transfusion in 24,112 patients with acute coronary syndromes enrolled in three large trials. Ten percent of the patients received at least 1 blood transfusion during their hospitalization, and they were older and had more complex comorbidity.

At 30 days, the group that had received blood had higher rates of death (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 3.94, 95% CI 3.26–4.75) and the combined outcome of death or myocardial infarction (HR 2.92, 95% CI 2.55–3.35). Transfusion in patients whose nadir hematocrit was higher than 25% was associated with worse outcomes.

This study suggests being cautious about routinely transfusing blood in stable patients with ischemic heart disease solely on the basis of arbitrary hematocrit levels.

Carson et al,21 however, in a later trial, found a trend toward worse outcomes with a restrictive strategy than with a liberal one. Here, 110 patients with acute coronary syndrome or stable angina undergoing cardiac catheterization were randomized to a target hemoglobin level of either at least 8 mg/dL or at least 10 g/dL. The primary outcome (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or unscheduled revascularization 30 days after randomization) occurred in 14 patients (25.5%) in the restrictive group and 6 patients (10.9%) in the liberal group (P = .054), and 7 (13.0%) vs 1 (1.8%) of the patients died (P = .032).

Murphy et al22 similarly found trends toward worse outcomes with a restrictive strategy in cardiac patients. The investigators randomized 2,007 elective cardiac surgery patients with a postoperative hemoglobin level lower than 9 g/dL to a hemoglobin transfusion threshold of either 7.5 or 9 g/dL. Outcomes (restrictive vs liberal strategies):

- Transfusion rates 53.4% vs 92.2%

- Rates of the primary outcome (a serious infection [sepsis or wound infection] or ischemic event [stroke, myocardial infarction, mesenteric ischemia, or acute kidney injury] within 3 months):

35.1% vs 33.0%, OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.91–1.34, P = .30) - Mortality rates 4.2% vs 2.6%, HR 1.64, 95% CI 1.00–2.67, P = .045

- Total costs did not differ significantly between the groups.

These studies21,22 suggest the need for more definitive trials in patients with active coronary disease and in cardiac surgery patients.

Holst et al23 randomized 998 intensive care patients in septic shock to hemoglobin thresholds for transfusion of 7 vs 9 g/dL. Mortality rates at 90 days (the primary outcome) were 43.0% vs 45.0%, RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.78–1.09, P = .44.

This study suggests that even in septic shock, a liberal transfusion strategy has no advantage over a parsimonious one.

Active bleeding, especially active gastrointestinal bleeding, poses a significant stress that may trigger empirical transfusion even without evidence of the real hemoglobin level.

Villanueva et al24 randomized 921 patients with severe acute upper-gastrointestinal bleeding to two groups, with hemoglobin transfusion triggers of 7 vs 9 g/dL. The findings were impressive:

- Freedom from transfusion 51% vs 14% (P < .001)

- Survival rates at 6 weeks 95% vs 91% (HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.33–0.92, P = .02)

- Rebleeding 10% vs 16% (P = .01).

Patients with peptic ulcer disease as well as those with cirrhosis stage Child-Pugh class A or B had higher survival rates with a restrictive transfusion strategy.

The RELIEVE trial25 compared the effect of a restrictive transfusion strategy in elderly patients on mechanical ventilation in 6 intensive care units in the United Kingdom. Transfusion triggers were hemoglobin 7 vs 9 g/dL, and the mortality rate at 180 days was 55% vs 37%, RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.44–1.05, P = .073.

Meta-analyses and observational studies

Rohde et al26 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 trials with 7,456 patients, which revealed that a restrictive strategy is associated with a lower risk of nosocomial infection, including pneumonia, wound infection, and sepsis.

The pooled risk of all serious infections was 10.6% in the restrictive group and 12.7% in the liberal group. Even after adjusting for the use of leukocyte reduction, the risk of infection was lower in the restrictive strategy group (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.69–0.99). With a hemoglobin threshold of less than 7.0 g/dL, the risk of serious infection was 14% lower. Although this was not statistically significant overall (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.72–1.02), the difference was statistically significant in the subgroup undergoing orthopedic surgery (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.53–0.97) and the subgroup presenting with sepsis (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.28–0.95).

Salpeter et al27 performed a meta-analysis and systematic review of three randomized trials (N = 2,364) comparing a restrictive hemoglobin transfusion trigger (hemoglobin < 7 g/dL) vs a more liberal trigger. The groups with restrictive transfusion triggers had lower rates of:

- In-hospital mortality (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60–0.92)

- Total mortality (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.65–0.98)

- Rebleeding (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45–0.90)

- Acute coronary syndrome (RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.22–0.89)

- Pulmonary edema (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.33–0.72)

- Bacterial infections (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73–1.00).

Wang et al28 performed a meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials in patients with upper-gastrointestinal bleeding comparing restrictive (hemoglobin < 7 g/dL) vs liberal transfusion strategies. The primary outcomes were death and rebleeding. The restrictive strategy was associated with:

- A lower mortality rate (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31–0.87, P = .01)

- A lower rebleeding rate (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.03–2.10, P = .21)

- Shorter hospitalizations (P = .009)

- Less blood transfused (P = .0005).

Vincent et al,29 in a prospective observational study of 3,534 patients in intensive care units in 146 facilities in Western Europe, found a correlation between transfusion and mortality. Transfusion was done most often in elderly patients and those with a longer stay in the intensive care unit. The 28-day mortality rate was 22.7% in patients who received a transfusion and 17.1% in those who did not (P = .02). The more units of blood the patients received, the more likely they were to die, and receiving more than 4 units was associated with worse outcomes (P = .01).

Dunne et al30 performed a study of 6,301 noncardiac surgical patients in the Veterans Affairs Maryland Healthcare System from the National Veterans Administration Surgical Quality Improvement Program from 1995 to 2000. Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that the composite of low hematocrit before and after surgery and high transfusion rates (> 4 units per hospitalization) were associated with higher rates of death (P < .01) and postoperative pneumonia (P ≤ .05) and longer hospitalizations (P < .05). The risk of pneumonia increased proportionally with the decrease in hematocrit.

These findings support pharmacologic optimization of anemia with hematinic supplementation before surgery to decrease the risk of needing a transfusion, often with parenteral iron. The fact that the patient’s hemoglobin can be optimized preoperatively by nontransfusional means may decrease the likelihood of blood transfusion, as the hemoglobin will potentially remain above the transfusion threshold. For example, if a patient has a preoperative hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL, and it is optimized up to 12, then if postoperatively the hemoglobin level drops 3 g/dL instead of reaching the threshold of 7 g/dL, the nadir will be just 9 g/dL, far above that transfusion threshold.

Brunskill et al,31 in a Cochrane review of 6 trials with 2,722 patients undergoing surgery for hip fracture, found no difference in rates of mortality, functional recovery or postoperative morbidity with a restrictive transfusion strategy (hemoglobin target > 8 g/dL vs a liberal one (> 10 g/dL). However, the quality of evidence was rated as low. The authors concluded that there is no justification for liberal red blood cell transfusion thresholds (10 g/dL), and a more restrictive transfusion threshold is preferable.

Weinberg et al32 found that, in trauma patients, receiving more than 6 units of blood was associated with poor prognosis, and outcomes were worse when the blood was older than 2 weeks. However, the effect of blood age is not significant when using smaller transfusion volumes (1 to 2 units of red blood cells).

Studies in sickle cell disease

Sickle cell disease patients have high levels of hemoglobin S, which causes erythrocyte sickling and increases blood viscosity. Transfusion with normal erythrocytes increases the amount of hemoglobin A (the normal variant).33,34

In trials in surgical patients,35,36 conservative strategies for preoperative blood transfusion aiming at a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL were as effective in preventing postoperative complications as decreasing the hemoglobin S levels to 30% by aggressive exchange transfusion.35

In nonsurgical patients, blood transfusion should be based on formal risk-benefit assessments. Therefore, the expert panel report on sickle cell management advises against blood transfusion in sickle cell patients with uncomplicated vaso-occlusive crises, priapism, asymptomatic anemia, or acute kidney injury in the absence of multisystem organ failure.34

Is hemoglobin the most relevant marker?

Most studies that compared restrictive and liberal transfusion strategies focused on using a lower hemoglobin threshold as the transfusion trigger, not on using fewer units of blood. Is the amount of blood transfused more important than the hemoglobin threshold? Perhaps a study focused both on a restrictive vs liberal strategy and also on the minimum amount of blood that each patient may benefit from would help to answer this question.

We should beware of routinely using the hemoglobin concentration as a threshold for transfusion and a surrogate marker of transfusion benefit because changes in hemoglobin concentration may not reflect changes in absolute red cell mass.37 Changes in plasma volume (an increase or decrease) affect the hematocrit concentration without necessarily affecting the total red cell mass. Unfortunately, red cell mass is very difficult to measure; hence, the hemoglobin and hematocrit values are used instead. Studies addressing changes in red cell mass may be needed, perhaps even to validate using the hemoglobin concentration as the sole indicator for transfusion.

Is fresh blood better than old blood?

Using blood that is more than 14 days old may be associated with poor outcomes, for several possible reasons. Red blood cells age rapidly in refrigeration, and usually just 75% may remain viable 24 hours after phlebotomy. Adenosine triphosphate and 2,3-DPG levels steadily decrease, with a consequent decrease in capacity for appropriate tissue oxygen delivery. In addition, loss of membrane phospholipids causes progressive rigidity of the red cell membrane with consequent formation of echynocytes after 14 to 21 days.38,39

The use of blood more than 14 days old in cardiac surgery patients has been associated with worse outcomes, including higher rates of death, prolonged intubation, acute renal failure, and sepsis.40 Similar poor outcomes have been seen in trauma patients.32

Lacroix et al,41 in a multicenter, randomized trial in critically ill adults, compared the outcomes of transfusion of fresh packed red cells (stored < 8 days) or old blood (stored for a mean of 22 days). The primary outcome was the mortality rate at 90 days: 37.0% in the fresh-blood group vs 35.3% in the old-blood group (HR 1.1, 95% CI 0.9–1.2, P = .38).

The authors concluded that using fresh blood compared with old blood was not associated with a lower 90-day mortality rate in critically ill adults.

RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH TRANSFUSION

Infections

The risk of infection from blood transfusion is small. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is transmitted in 1 in 1.5 million transfused blood components, and hepatitis C virus in 1 in 1.1 million; these odds are similar to those of having a fatal airplane accident (1 in 1.7 million per flight). Hepatitis B virus infection is more common, the reported incidence being 1 in 357,000.42

Noninfectious complications

Transfusion-associated circulatory overload occurs in 4% to 6% of patients who receive a transfusion. Therefore, circulatory overload is a greater danger from transfusion than infection is.42

Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions occur in 1.1% of patients with prestorage leukoreduction.

Transfusion-associated acute lung injury occurs in 0.8 per 10,000 blood components transfused.

Errors associated with blood transfusion include, in decreasing order of frequency, transfusion of the wrong blood component, handling and storage errors, inappropriate administration of anti-D immunoglobulin, and avoidable, delayed, or insufficient transfusions.43

Surgery and condition-specific complications of red blood cell transfusion

Cardiovascular surgery. Transfusion is associated with a higher risk of postoperative stroke, respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, prolonged intubation time, reintubation, in-hospital death, sepsis, and longer postoperative length of stay.44

Malignancy. The use of blood in this setting has been found to be an independent predictor of recurrence, decreased survival, and increased risk of lymphoplasmacytic and marginal-zone lymphomas.44–47

Vascular, orthopedic, and other surgeries. Transfusion is associated with a higher risk of death, thromboembolic events, acute kidney injury, death, composite morbidity, reoperation, sepsis, and pulmonary complications.44

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, sepsis, and intensive care unit admissions. Transfusion is associated with an increased risk of rebleeding, death, and secondary infections.44

COST OF RED BLOOD CELL TRANSFUSION

Up to 85 million units of red blood cells are transfused per year worldwide, 15 million of them in the United States.42 At our hospital in 2013, 1 unit of leukocyte-reduced red blood cells cost $957.27, which included the costs of acquisition, processing, banking, patient testing, administration, and monitoring.

The Premier Healthcare Alliance48 analyzed data from 7.4 million discharges from 464 hospitals between April 2011 and March 2012. Blood use varied significantly among hospitals, and the hospitals in the lowest quartile of blood use had better patient outcomes. If all the hospitals used as little blood as those in the lowest quartile and had outcomes as good, blood product use would be reduced by 802,716 units, with savings of up to $165 million annually.

In addition to the economic cost of blood transfusion, the clinician must be aware of the cost in terms of comorbidities caused by unnecessary blood transfusion.49,50

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE AABB

In view of all the current compelling evidence, a restrictive approach to transfusion is the single best strategy to minimize adverse outcomes.51 Below, we outline the current recommendations from the AABB (formerly the American Association of Blood Banks),42 which are similar to the national clinical guideline on blood transfusion in the United Kingdom,52 and have recently been updated, confirming the initial recommendations.53

In critical care patients, transfusion should be considered if the hemoglobin concentration is 7 g/dL or less.

In postoperative patients and hospitalized patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease, transfusion should be considered if the hemoglobin concentration is 8 g/dL or less or if the patient has signs or symptoms of anemia such as chest pain, orthostatic hypotension, or tachycardia unresponsive to fluid resuscitation, or heart failure.

In hemodynamically stable patients with acute coronary syndrome, there is not enough evidence to allow a formal recommendation for or against a liberal or restrictive transfusion threshold.

Consider both the hemoglobin concentration and the symptoms when deciding whether to give a transfusion. This recommendation is shared by a National Institutes of Health consensus conference,54 which indicates that multiple factors related to the patient’s clinical status and oxygen delivery should be considered before deciding to transfuse red blood cells.

The Society of Hospital Medicine55 and the American Society of Hematology56 concur with a parsimonious approach to blood use in their Choosing Wisely campaigns. The American Society of Hematology recommends that if transfusion of red blood cells is necessary, the minimum number of units should be given that relieve the symptoms of anemia or achieve a safe hemoglobin range (7–8 g/dL in stable noncardiac inpatients).57

New electronic tools can monitor the ordering and use of blood products in real time and can identify the hemoglobin level used as the trigger for transfusion. They also provide data on blood use by physician, hospital, and department. These tools can reveal current practice at a glance and allow sharing of best practices among peers and institutions.52

CONSIDER TRANSFUSION FOR HEMOGLOBIN BELOW 7 G/DL

The routine use of blood has come under scrutiny, given its association with increased healthcare costs and morbidity. The accepted practice in stable medical patients is a restrictive threshold approach for blood transfusion, which is to consider (not necessarily give) a single unit of packed red blood cells for a hemoglobin less than 7 g/dL.

However, studies in acute coronary syndrome patients and postoperative cardiac surgery patients have not shown the restrictive threshold to be superior to a liberal threshold in terms of outcomes and costs. This variability suggests the need for further studies to determine the best course of action in different patient subpopulations (eg, surgical, oncologic, trauma, critical illness).

Also, a limitation of most of the clinical studies was that only the hemoglobin concentration was used as a marker of anemia, with no strict assessment of changes in red cell mass with transfusion.

Despite the variability in certain populations, the overall weight of current evidence favors a restrictive approach to blood transfusion (hemoglobin < 7 g/dL), although perhaps in patients who have active coronary disease or are undergoing cardiac surgery, a more lenient threshold (< 8 g/dL) for transfusion should be considered.

For decades, physicians believed in the benefit of prompt transfusion of blood to keep the hemoglobin level at arbitrary, optimum levels, ie, close to normal values, especially in the critically ill, the elderly, and those with coronary syndromes, stroke, or renal failure.

However, the evidence supporting arbitrary hemoglobin values as an indication for transfusion was weak or nonexistent. Also, blood transfusion can have complications and adverse effects, and blood is costly and scarce. These considerations prompted research into when blood transfusion should be considered, and recommendations that it should be used more sparingly than in the past.

This review offers a perspective on the evidence supporting restrictive blood use. First, we focus on hemodilution studies that demonstrated that humans can tolerate anemia. Then, we look at studies that compared a restrictive transfusion strategy with a liberal one in patients with critical illness and active bleeding. We conclude with current recommendations for blood transfusion.

EVIDENCE FROM HEMODILUTION STUDIES

Hemoglobin is essential for tissue oxygenation, but the serum hemoglobin concentration is just one of several factors involved.1–5 In anemia, the body can adapt not only by increasing production of red blood cells, but also by:

- Increasing cardiac output

- Increasing synthesis of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG), with a consequent shift in the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve to the right, allowing enhanced release of oxygen at the tissue level

- Moving more carbon dioxide into the blood (the Bohr effect), which decreases pH and also shifts the dissociation curve to the right.

Just 20 years ago, physicians were using arbitrary cutoffs such as hemoglobin 10 g/dL or hematocrit 30% as indications for blood transfusion, without reasonable evidence to support these values. Not until acute normovolemic hemodilution studies were performed were we able to progressively appraise how well patients could tolerate lower levels of hemoglobin without significant adverse outcomes.

Acute normovolemic hemodilution involves withdrawing blood and replacing it with crystalloid or colloid solution to maintain the volume.6

Initial studies were done in animals and focused on the safety of acute anemia regarding splanchnic perfusion. Subsequently, studies proved that healthy, elderly, and stable cardiac patients can tolerate acute anemia with normal cardiovascular response. The targets in these studies were modest at first, but researchers aimed progressively for more aggressive hemodilution with lower hemoglobin targets and demonstrated that the body can tolerate and adapt to more severe anemia.6–8

Studies in healthy patients

Weiskopf et al9 assessed the effect of severe anemia in 32 conscious healthy patients (11 presurgical patients and 21 volunteers not undergoing surgery) by performing acute normovolemic hemodilution with 5% human albumin, autologous plasma, or both, with a target hemoglobin level of 5 g/dL. The process was done gradually, obtaining aliquots of blood of 500 to 900 mL. Cardiac index increased, along with a mild increase in oxygen consumption with no increase in plasma lactate levels, suggesting that in conscious healthy patients, tissue oxygenation remains adequate even in severe anemia.

Leung et al10 addressed the electrocardiographic changes that occur with severe anemia (hemoglobin 5 g/dL) in 55 healthy volunteers. Three developed transient, reversible ST-segment depression, which was associated with a higher heart rate than in the volunteers with no electrocardiographic changes; however, the changes were reversible and asymptomatic, and thus were considered physiologic and benign.

Hemodilution in healthy elderly patients

Spahn et al11 performed 6 and 12 mL/kg isovolemic exchange of blood for 6% hydroxyethyl starch in 20 patients older than 65 years (mean age 76, range 65–88) without underlying coronary disease.

The patients’ mean hemoglobin level decreased from 11.6 g/dL to 8.8 g/dL. Their cardiac index and oxygen extraction values increased adequately, with stable oxygen consumption during hemodilution. There were no electrocardiographic signs of ischemia.

Hemodilution in coronary artery disease

Spahn et al12 performed hemodilution studies in 60 patients (ages 35–81) with coronary artery disease managed chronically with beta-blockers who were scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Hemodilution was performed with 6- and 12-mL/kg isovolemic exchange of blood for 6% hydroxyethyl starch maintaining normovolemia and stable filling pressures. Hemoglobin levels decreased from 12.6 g/dL to 9.9 g/dL. The hemodilution process was done before the revascularization. The authors monitored hemodynamic variables, ST-segment deviation, and oxygen consumption before and after each hemodilution.

There was a compensatory increase in cardiac index and oxygen extraction with consequent stable oxygen consumption. These changes were independent of patient age or left ventricular function. In addition, there were no electrocardiographic signs of ischemia.

Licker et al13 studied the hemodynamic effect of preoperative hemodilution in 50 patients with coronary artery disease undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery, performing transesophageal echocardiography before and after hemodilution. The patients underwent isovolemic exchange with iso-oncotic starch to target a hematocrit of 28%.

Acute normovolemic hemodilution triggered an increase in cardiac stroke volume, which had a direct correlation with an increase in the central venous pressure and the left ventricular end-diastolic area. No signs of ischemia were seen in these patients on electrocardiography or echocardiography (eg, left ventricular wall-motion abnormalities).

Hemodilution in mitral regurgitation

Spahn et al14 performed acute isovolemic hemodilution with 6% hydroxyethyl starch in 20 patients with mitral regurgitation. The cardiac filling pressures were stable before and after hemodilution; the mean hemoglobin value decreased from 13 to 10.3 g/dL. The cardiac index and oxygen extraction increased proportionally, with stable oxygen consumption; these findings were the same regardless of whether the patient was in normal sinus rhythm or atrial fibrillation.

Effect of hemodilution on cognition

Weiskopf et al15 assessed the effect of anemia on executive and memory function by inducing progressive acute isovolemic anemia in 90 healthy volunteers (age 29 ± 5), reducing their hemoglobin values to 7, 6, and 5 g/dL and performing repetitive neuropsychological and memory testing before and after the hemodilution, as well as after autologous blood transfusion to return their hemoglobin level to 7 g/dL.

There were no changes in reaction time or error rate at a hemoglobin concentration of 7 g/dL compared with the performance at a baseline hemoglobin concentration of 14 g/dL. The volunteers got slower on a mathematics test at hemoglobin levels of 6 g/dL and 5 g/dL, but their error rate did not increase. Immediate and delayed memory were significantly impaired at hemoglobin of 5 g/dL but not at 6 g/dL. All tests normalized with blood transfusion once the hemoglobin level reached 7 g/dL.15

Weiskopf et al16 subsequently investigated whether giving supplemental oxygen to raise the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (Pao2) to 350 mm Hg or greater would overcome the neurocognitive effects of severe acute anemia. They followed a protocol similar to the one in the earlier study15 and induced anemia in 31 healthy volunteers, age 28 ± 4 years, with a mean baseline hemoglobin concentration of 12.7 g/dL.

When the volunteers reached a hemoglobin concentration of 5.7 ± 0.3 g/dL, they were significantly slower on the mathematics test, and their delayed memory was significantly impaired. Then, in a double-blind fashion, they were given either room air or oxygen. Oxygen increased the Pao2 to 406 mm Hg and normalized neurocognitive performance.

Hemodilution studies in surgical patients

A 2015 meta-analysis17 of 63 studies involving 3,819 surgical patients compared the risk of perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion as well as the overall volume of transfused blood in patients undergoing preoperative acute normovolemic hemodilution vs a control group. Though the overall data showed that the patients who underwent acute normovolemic hemodilution needed fewer transfusions and less blood (relative risk [RR] 0.74, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.63–0.88, P = .0006), the authors noted significant heterogeneity and publication bias.

However, the hemodilution studies paved the way for justifying a more conservative and restrictive transfusion strategy, with a hemoglobin cutoff value of 7 g/dL, and in acute anemia, using oxygen to overcome acute neurocognitive effects while searching for and correcting the cause of the anemia.

STUDIES OF RESTRICTIVE VS LIBERAL TRANSFUSION STRATEGIES

Studies in critical care and high-risk patients

Hébert et al18 randomized 418 critical care patients to a restrictive transfusion approach (in which they were given red blood cells if their hemoglobin concentration dropped below 7.0 g/dL) and 420 patients to a liberal strategy (given red blood cells if their hemoglobin concentration dropped below 10.0 g/dL). Mortality rates (restrictive vs liberal strategy) were as follows:

- Overall at 30 days 18.7% vs 23.3%, P = .11

- In the subgroup with less-severe disease (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II [APACHE II] score < 20), 8.7% vs 16.1%, P = .03

- In the subgroup under age 55, 5.7% vs 13%, P = .02

- In the subgroup with clinically significant cardiac disease, 20.5% vs 22.9%, P = .69

- In the hospital, 22.2% vs 28.1%; P = .05.

This study demonstrated that parsimonious blood use did not worsen clinical outcomes in critical care patients.