User login

Nutrition

Malnutrition is present in 20% to 50% of hospitalized patients.1, 2 Despite simple, validated screening tools, malnutrition tends to be underdiagnosed.3, 4 Over 90% of elderly patients transitioning from an acute care hospital to a subacute care facility are either malnourished or at risk of malnutrition.5 Malnutrition has been associated with increased risk of nosocomial infections,6 worsened discharge functional status,7 and higher mortality,8 as well as longer lengths of stay7, 8 and higher hospital costs.2

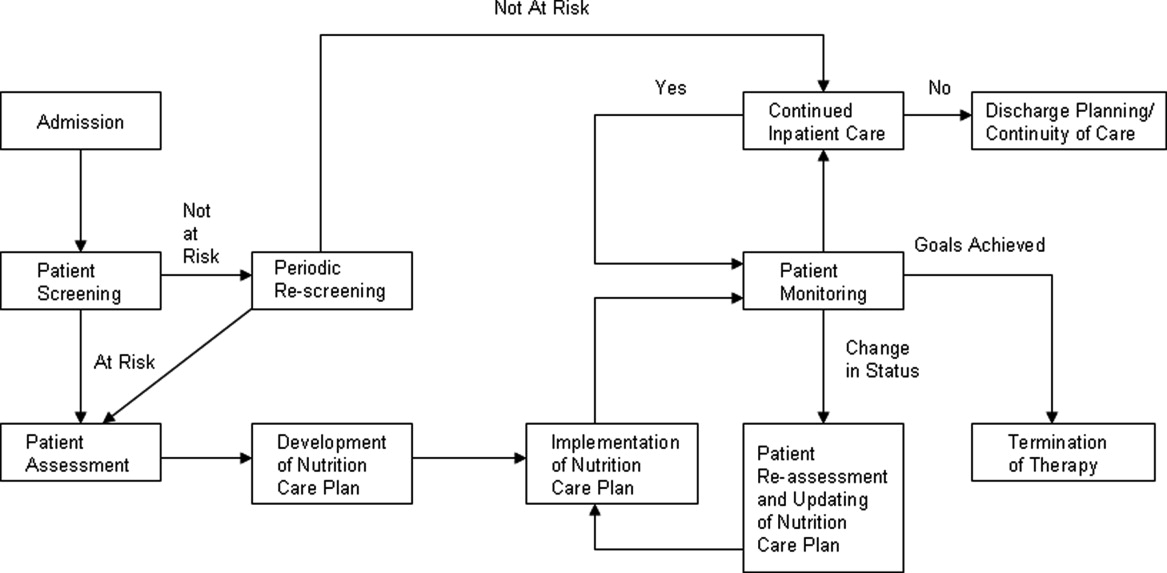

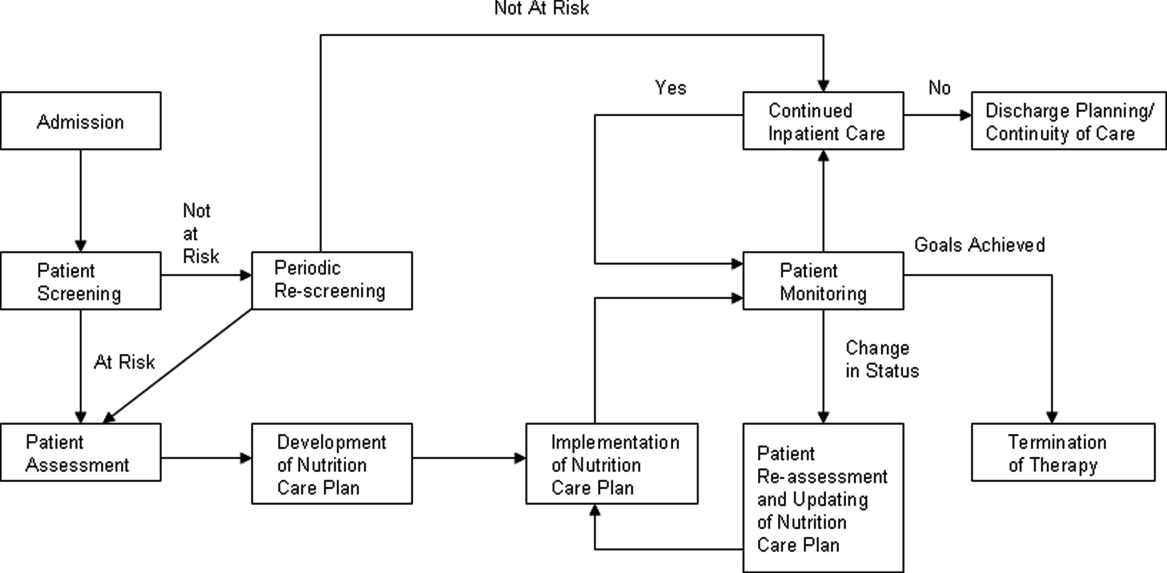

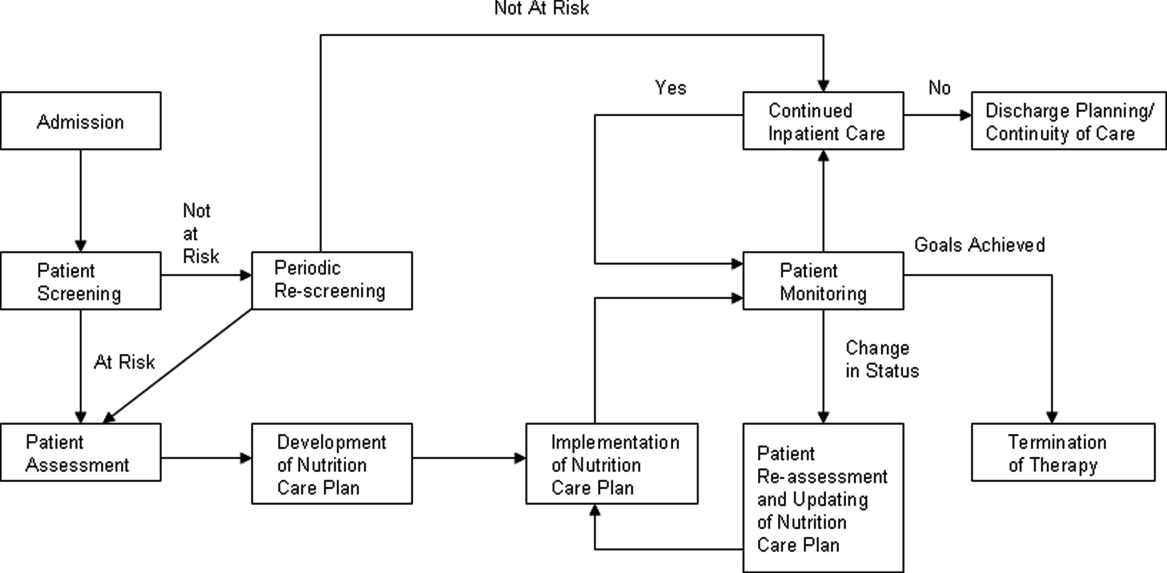

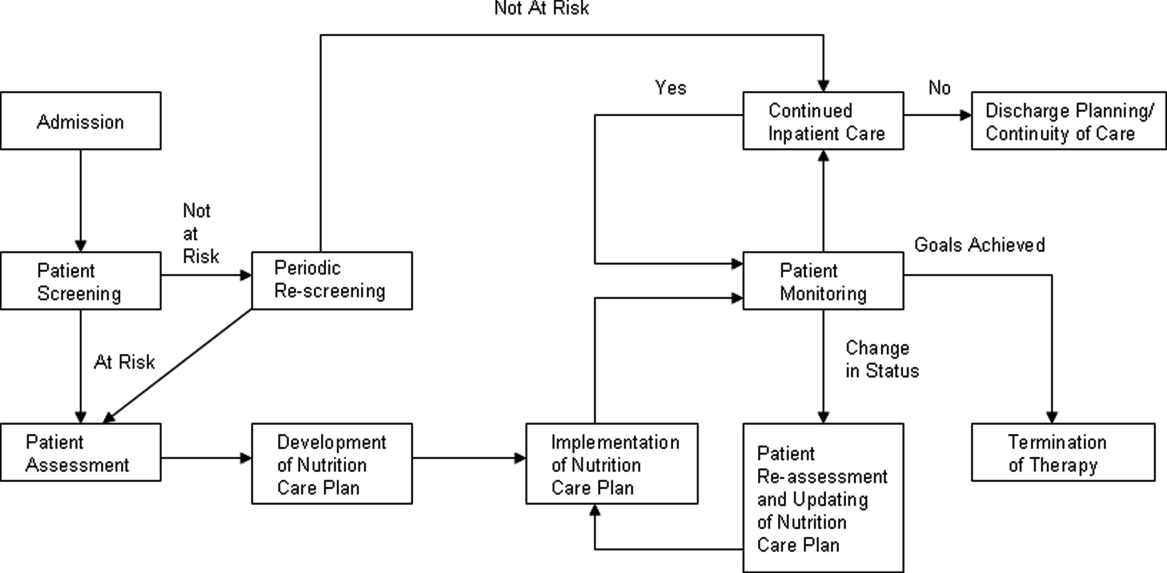

Malnutrition describes either overnutrition or undernutrition that causes a change in body composition and decreased function.9 Malnutrition in hospitalized patients is typically related to undernutrition due to either reduced intake or increased metabolic rate. Reasons for reduced intake include poor appetite, reduced ability to chew or swallow, and nil per os (NPO) status. Patients with acute or chronic illnesses may either be malnourished on admission, or develop malnutrition within a few days of hospital admission, due to the effects of the inflammatory state on metabolism. Given that malnutrition is potentially modifiable, it is important to screen for malnutrition and, when present, develop, implement, and monitor a nutrition care plan10 (Figure 1).

The purpose of this review is to provide the hospitalist with an overview of screening, assessment, and development and implementation of a nutrition care plan in the acutely ill hospitalized patient.

PATIENT SCREENING

Nutrition screening identifies patients with nutritional deficits who may benefit from further detailed nutrition assessment and intervention.11 The Joint Commission requires that all patients admitted to acute care hospitals be screened for risk of malnutrition within 24 hours.12 Those considered at risk for malnutrition have significant weight changes, chronic disease or an acute inflammatory process, or have been unable to ingest adequate calories for 7 days.13

Those not at risk should be regularly rescreened throughout their hospital stay. The American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) recommends that institutions create and approve a screening process according to the patient population served.10 There are several tools validated for use in the acute care setting.14 Many institutions trigger an automatic nutrition consult when certain screening criteria are met.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

Nutrition assessment should be performed by a dietitian or nutrition consult provider in patients who screen at risk for malnutrition to characterize and determine the cause of nutritional deficits.10 The nutrition assessment identifies history and physical examination elements to diagnose malnutrition. An ASPEN consensus statement recommends the diagnosis of malnutrition if 2 or more of the following are present: insufficient energy intake, weight loss, loss of muscle mass, loss of subcutaneous fat, localized or generalized fluid accumulation, and decreased functional status measured by hand‐grip strength.9 The nutrition assessment should also consider how long the patient has been without adequate nutrition, document baseline nutrition parameters,15 and estimate caloric requirements to determine nutrition support therapy needs.10 Nutrition assessment typically includes the following components.

History

A careful history elicits the majority of information needed to determine the cause and severity of malnutrition.16 Patients should be questioned about a typical day's oral intake prior to hospitalization, and about factors that affect their intake such as sensory deficits, fine motor dysfunction, or chewing and swallowing difficulties, which often decline in chronically ill and elderly patients. Nutrition may be affected by financial difficulties or limited social support, and access to food should be assessed.

Physical Findings

Weight loss is the best physical exam predictor of malnutrition risk, although nutritional depletion can occur in a very short time in acutely ill or injured patients before substantial weight loss has occurred. The likelihood of malnutrition is increased if a patient has: a body mass index (BMI) <18.5 kg/m2; unintentional loss of >2.3 kg (5 lb) or 5% of body weight over 1 month; and unintentional loss of >4.5 kg (10 lb) or 10% of body weight over 6 months.17 Weight loss may be masked by fluid retention from chronic conditions, such as heart failure, or from volume resuscitation in the acutely ill patient.9, 16

Body mass index can be misleading, as age‐related height loss may artificially increase BMI, and height may be difficult to accurately measure in a kyphotic, unsteady, or bedridden patient. The clinician may find evidence of loss of subcutaneous fat or muscle mass in patients with chronic illness, but these findings may not be evident in the acutely ill patient.9 Other physical exam assessments of malnutrition, such as arm span, skinfold thickness, and arm circumference are not reliable.16

Laboratory Tests

Biochemical markers, including transferrin, albumin, and prealbumin, have not been proven as accurate predictors of nutrition status because they may change as a result of other factors not related to nutrition.15, 18 Serum albumin, for example, may be more reflective of the degree of metabolic stress.19 Prealbumin has a serum half‐life much shorter than albumin or transferrin (approximately 2448 hours) and is perhaps the most useful protein marker to assess the adequacy of nutritional replacement after the inflammatory state is resolved.18

Calculating Caloric Requirements

Energy expenditure measurement is considered the gold standard to determine patients' caloric needs. Actual measurement by methods such as indirect calorimetry, which measures oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production, and calculates energy expenditure, is challenging in everyday clinical settings. Predictive equations often are used as alternative methods to estimate patients' caloric requirements.20 There is no consensus among the 3 North American societies' guidelines (the Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines; the American Dietetics Association's evidence‐based guideline for critical illness; and the Society of Critical Care Medicine and American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition's joint guideline) as to the best method.21

In the simplest equation, caloric needs are estimated by calories per kilogram.22 In obese patients, using actual body weight will overestimate needs, but using ideal body weight may cause underfeeding. A small study comparing predictive equations in obese hospitalized patients found the Harris‐Benedict equations (H‐BE) using adjusted body weight and a stress factor to be most accurate, but only in 50% of patients.23 Most clinicians are familiar with the H‐BE, but alternatives such as calories per kilogram or the Mifflin St.‐Jeor equation24 are often used (S. Brantley (May 5, 2012), S. Lundy (May 23, 2012), personal communication).

Indications for Nutritional Intervention

In adults without preexisting malnutrition, inadequate nutritional intake for approximately 714 days should prompt nutritional intervention.25, 26 This timeline should be shorter (37 days) in those with lower energy reserves (eg, underweight or recent weight loss) or significant catabolic stress (eg, acutely ill patients).27, 28 Other patient populations shown to benefit from nutritional intervention include: postoperative patients who are anticipated to be NPO for more than 7 days or to be taking less than 60% of estimated caloric needs by postoperative day 10; preoperative patients with severe malnutrition29; those with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing elective surgery30; and stroke patients with persistent dysphagia for more than 7 days.31

DEVELOPMENT OF A NUTRITION CARE PLAN

The formal nutrition assessment of the at‐risk patient derives the information needed for the development of a nutrition care plan. This plan guides the provision of nutrition therapy, the intervention, the monitoring protocols, evaluation, and reassessment of nutrition goals or termination of specialized nutrition support.10 Assessments for adequacy of nutritional repletion are best done by repeated screening and physical examinations.18

IMPLEMENTATION OF NUTRITION CARE PLAN

Nutritional interventions include dietary modifications, enteral nutrition, and parenteral nutrition.

Dietary Modifications

The purpose of the diet is to provide the necessary nutrients to the body in a well‐tolerated form. Diets can be modified to provide for individual requirements, personal eating patterns and food preferences, and disease process and digestive capacity. Dietary adjustments include change in consistency of foods (eg, pureed, mechanical soft), increase or decrease in energy value, increase or decrease in the type of food or nutrient consumed (eg, sodium restriction, fiber enhancement), elimination of specific foods (eg, gluten‐free diet), adjustment in protein, fat, and carbohydrate content (eg, ketogenic diet, renal diet, cholesterol‐lowering diet), and adjustment of the number and frequency of meals.32

Dietary supplementation (eg, Boost, Ensure) is common practice in persons diagnosed with such conditions as cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Supplements enhance the diet by increasing the total daily intake of a vitamin, a mineral, an amino acid, an herb or other botanical33, and should not be used as a meal substitute.34 These supplements are varied in content of calories, protein, vitamins, and minerals. Various flavors and consistencies are also available. Several oral supplements are reviewed in Table 1.

| Oral Supplement* (Serving Size; mL) | Kcal/svg | Protein (g/svg) | Fat (g/svg) | CHO (g/svg) | Na (mg/svg) | K (mg/svg) | Ca (mg/svg) | Phos (mg/svg) | Mg (mg/svg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Boost Original (237) | 240 | 10 | 4 | 41 | 150 | 460 | 300 | 300 | 100 |

| Ensure Nutrition Shake (237) | 250 | 9 | 6 | 40 | 200 | 370 | 300 | 250 | 100 |

| Carnation Instant Breakfast Ready to Drink (325) | 250 | 14 | 5 | 34 | 180 | 330 | 500 | 500 | 120 |

| Resource Breeze (fruit‐flavored) clear liquid (237) | 250 | 9 | 0 | 54 | 80 | 10 | 10 | 150 | 1 |

| Glucerna 1.0 Ready to Drink low‐CHO (237) | 240 | 10 | 13 | 23 | 220 | 370 | 170 | 170 | 67 |

| Re/Gen low K and Phos (180) | 375 | 12 | 17 | 47 | 180 | 23 | 15 | 68 | 3 |

Enteral Nutrition

Enteral nutrition (EN) support should be provided to patients who have functioning gastrointestinal (GI) tracts but are unable to take adequate calories orally. Compared to parenteral nutrition (PN), EN is associated with favorable improvements in inflammatory cytokines, acute phase proteins, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, nosocomial infections, mortality, and cost.35 Enteral feeds are more physiologic than parenteral feeds, maintain GI structure and integrity, and avoid intravenous (IV) access complications. Patients with normal nutritional status on admission who require EN should be receiving over 50% of their caloric needs within the first week of hospital stay.25 Malnourished patients should reach this minimum goal within 35 days of admission.27, 28 EN is not contraindicated in the absence of bowel sounds or in the presence of increased gastric residuals.35 Withholding enteral feedings for gastric residual volumes <250 mL36, 37 or reduced bowel sounds can result in inadequate caloric intake or inappropriate use of PN.27

Gastric feedings are more physiologic than small bowel feedings, can be given by bolus or continuous infusion, and can be given by tubes that are easy to place at the bedside. Post‐pyloric feedings (nasoduodenal or nasojejunal) may be associated with a lower risk of pneumonia, and should be considered in high‐risk patients such as those receiving continuous sedatives or neuromuscular blockers.36 Post‐pyloric tube placement usually requires endoscopy, fluoroscopy, or electromagnetic guidance. Percutaneous feeding tubes (gastrostomy or jejunostomy) should be considered in those who require tube feedings for longer than 30 days.38

Assessment of patient requirements and disease state, as well as extensive knowledge of available formulas, is important in the selection of the appropriate enteral formula.39 Standardized formulas are used for most patients. The provision of adequate water must be considered with these formulas, particularly in the long‐term care and home settings.40 Many specialized formulas are designed for a particular disease state or condition, some of which are further reviewed in Table 2.

| Formula | Kcal/mL | Protein (g/L) | Fat (g/L) | CHO (g/L) | Osmolality (mOsm/kg H2O) | Na (mEq/L) | K (mEq/L) | Ca (mg/L) | Mg (mg/L) | Phos (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| Nutren 1.0‐low residue | 1 | 40 | 38 | 127 | 315 | 38 | 32 | 668 | 268 | 668 |

| Osmolite 1.0 Cal low residue | 1 | 44.3 | 34.7 | 143.9 | 300 | 40.4 | 40.2 | 760 | 305 | 1760 |

| Replete high protein, low residue | 1 | 62.4 | 34 | 112 | 300 | 38.1 | 38.5 | 1000 | 400 | 1000 |

| Replete Fiber high protein with fiber | 1 | 62.4 | 34 | 112 | 310 | 38.1 | 38.5 | 1000 | 400 | 1000 |

| Osmolite 1.5 low residue, calorically dense | 1.5 | 62.7 | 49.1 | 203.6 | 525 | 60.9 | 46 | 1000 | 400 | 1000 |

| Two Cal calorie and protein dense | 2 | 83.5 | 91 | 219 | 725 | 64 | 63 | 1050 | 425 | 1050 |

| Vivonex RTF‐elemental | 1 | 50 | 11.6 | 176 | 630 | 30.4 | 31 | 668 | 268 | 668 |

| Nepro with Carb Steady‐for electrolyte, fluid restriction (eg, dialysis) | 1.8 | 81 | 96 | 161 | 745 | 46 | 27 | 1060 | 210 | 720 |

| Nutren Glytrol low CHO | 1 | 45.2 | 47.6 | 100 | 280 | 32.2 | 35.9 | 720 | 286 | 720 |

| NutriHep‐for hepatic disease | 1.5 | 40 | 21.2 | 290 | 790 | 160 | 33.9 | 956 | 376 | 1000 |

If concerned about formula tolerance, one solution is to initiate the formula at a low rate and increase to the goal rate over 2448 hours. Dilution of enteral formulas is not necessary to assure optimal tolerance. Continuous feedings are recommended for most patients initially and after tolerance has been established, bolus feedings can be attempted if the feeding tube terminates in the stomach. Bolus feedings, where 240480 mL of formula are delivered through a syringe over 1015 minutes, may be more physiological for patients. This regimen can be repeated 46 times daily to meet nutrition goals.41

Parenteral Nutrition

PN provides macronutrients such as carbohydrates, protein, and fat; micronutrients such as vitamins, minerals, electrolytes, and trace elements are added in appropriate concentrations. PN may also provide the patient's daily fluid needs. The timing of PN initiation depends upon the patient's initial nutritional status. ASPEN does not recommend PN during the first 7 days of hospitalization in critically ill patients with normal nutritional status. If the patient is not receiving 100% of caloric needs from EN after 7 days, supplemental PN should be considered. However, if on admission a patient is already malnourished and EN is not feasible, PN should be initiated and continued until the patient is receiving at least 60% of caloric needs by enteral route.42 This includes patients with intestinal obstruction, ileus, peritonitis, malabsorption, high output enterocutaneous fistulae, intestinal ischemia, intractable vomiting and diarrhea, severe shock, and fulminant sepsis.10, 43

Standardized commercial PN products are available and reduce the number of steps required between ordering and administration, as compared to customized PN, which is compounded for a particular patient. However, despite improved efficiency and lower cost, there is no evidence that standardized preparations are safer to patients than customized solutions. Institutions utilizing standardized PN must also have a mechanism to customize formulas for those with complex needs.44

Creating a customized parenteral solution involves several basic steps. Total caloric requirement may be estimated using a predictive formula, as previously discussed; calories/kg of ideal body weight is the simplest method. Most hospitalized patients require 2030 calories/kg/d. Daily fluid requirement may be based on kilocalories (kcal) delivered, or by ideal body weight (eg, 1 mL/kcal or 3040 mL/kg). More fluid may be needed in patients with significant sensible or insensible losses; those with renal failure or heart failure should receive less fluid.

Protein needs are calculated by multiplying ideal body weight (kg) by estimated protein needs in g/kg/d (1.22 g/kg/d for catabolic patients). Protein should provide approximately 20% of total calories. Protein restriction is not required in renal impairment; acutely ill patients on renal replacement therapy should receive 1.51.8 g/kg/d. In hepatic failure patients, protein should be restricted only if hepatic encephalopathy fails to improve with other measures.

Knowing the protein, kcal, and fluid needs of the patient, the practitioner divides the remaining non‐protein calories between carbohydrates and fat. Approximately 70%85% of non‐protein calories should be provided as carbohydrates (dextrose), up to 7 g/kg/d. The other 15%30% are as fat, in lipid solutions, providing a maximum of 2.5 g/kg/d. Lipid solutions are provided as either 10% (1.1 kcal/mL) or 20% (2.2 kcal/mL) concentrations.43, 44 Propofol's contribution to fat intake complicates estimating total fat intake in critically ill patients.45

Standardized parenteral multivitamin preparations are available; the clinician must determine if preparations containing vitamin K are appropriate. Of the trace elements, copper and manganese should be restricted in hepatobiliary disease.44

Acutely ill patients receive PN as a 24‐hour infusion, to minimize its impact on volume status and energy expenditure,46 providing 50% of needs on infusion day one and reaching goal within 4872 hours, rather than cyclic infusions over shorter intervals. Daily assessments of vital signs, intake and output, and weight are necessary to monitor volume status.

Once a patient is taking at least 60% of caloric needs either by mouth or by EN, PN can be discontinued. Tapering the infusion is not required, as abrupt discontinuation has not been demonstrated to cause symptomatic hypoglycemia.47, 48

PATIENT MONITORING

Laboratory monitoring with nutrition support should include baseline electrolytes, glucose, renal function, coagulation studies, triglycerides, magnesium, phosphorus, cholesterol, platelet count, and hepatobiliary enzymes. Electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus should be checked daily for 3 days and, if normal, should then be checked biweekly. Capillary glucose should be monitored several times a day until stable. Weekly triglycerides, albumin, cholesterol, coagulation studies, and liver enzymes should also be checked in patients while on parenteral nutrition.25 Patients at risk for refeeding syndrome should have potassium, phosphate, calcium, and magnesium measured daily for 7 days, with repletion as necessary. These electrolytes should be monitored 3 times the following week if stable.49

Patients should be monitored clinically for gastrointestinal tolerance of enteral nutrition. All 3 North American guidelines recommend monitoring gastric residual volumes (GRV); however, there is no consensus on the volume considered to require intervention. Motility agents are recommended as first line treatment of high GRV.36, 37, 42 If high GRV continues, tube feeding should be held, and tube placement, medications, and metabolic assessment should be reviewed. Placement of a transpyloric feeding tube may be indicated.50

Adverse Effects and Complications of Nutrition Support

Regarding EN, complications include those related to tube placement and maintenance, infections, and medical complications of the feeds themselves. Some of the adverse effects of the enteral formulas may be attenuated. Diarrhea, which occurs in up to 20% of patients, may be avoided with slow feed advancement, use of low‐osmotic formulas, or fiber additives.51 Gastric distention and abdominal pain may improve with slow feed advancement and continuous (rather than bolus) feeds. Small‐bore tubes and acid‐reducing medications may decrease gastroesophageal reflux, and aspiration pneumonia may be avoided by semi‐recumbent positioning and post‐pyloric feeding.52

Complications of PN may be grouped as mechanical, infectious, and metabolic. The mechanical complications of central line placement include pneumothorax, arterial puncture, hematoma, air embolism, and line malpositioning. Catheter‐related deep venous thrombosis may occur. Patients on PN through a central line are at risk for central line‐associated bloodstream infections.25 The metabolic complications such as hyperglycemia, electrolyte disorders, hepatic steatosis, and volume overload may have severe consequences, such as heart failure or neuromuscular dysfunction, thus they require close attention.53

A complication of nutrition support that may occur regardless of route is the refeeding syndrome. Refeeding syndrome describes fluid shifts and electrolyte abnormalities that occur after initiation of oral, enteral, or parenteral nutrition in a malnourished or starved patient.54, 55 There are no formal criteria for diagnosing refeeding syndrome.

In the starved state, the body switches from carbohydrate to protein and fat metabolism. Reintroduction of carbohydrates stimulates insulin release with glycogen, fat, and protein synthesis. Associated uptake of glucose, potassium, magnesium, phosphate, and water into cells causes electrolyte and fluid abnormalities. Although hypophosphatemia is the hallmark of refeeding syndrome, it is not pathognomonic. Additional disturbances include hypokalemia, hyperglycemia, hypomagnesemia, thiamine deficiency, and fluid imbalance.49 Patients at risk of refeeding should have serum electrolytes, magnesium, phosphorus, and glucose checked before nutrition support starts. The degree of laboratory abnormalities, if any, and the clinical course of refeeding guides the frequency of subsequent blood tests.56 These consequences of refeeding can adversely affect every major organ system and may result in death.57

Starvation physiology underlies all risk factors for refeeding syndrome. In hospitalized patients, those at risk for refeeding include, but are not limited to, the elderly, oncology patients, postoperative patients, alcohol‐dependent patients, those with malabsorptive states, those who are fasting or chronically malnourished, and those on diuretic therapy.54, 57 The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) of England and Wales has published criteria to identify patients at high risk for refeeding (Table 3).56 Identification of at‐risk patients and attention to their nutritional needs prevents refeeding syndrome.

|

| Patient has 1 or more of the following: |

| BMI <16 kg/m2 |

| Unintentional weight loss >15% within the last 36 mo |

| Little or no nutritional intake for more than 10 d |

| Low levels of potassium, phosphate, or magnesium prior to feeding |

| Or patient has 2 or more of the following: |

| BMI <18.5 kg/m2 |

| Unintentional weight loss >10% within the last 36 mo |

| Little or no nutritional intake for more than 5 d |

| A history of alcohol abuse or drugs including insulin, chemotherapy, antacids, or diuretics |

ASPEN and NICE have each issued guidelines for initiating nutrition support in patients at risk for refeeding. ASPEN guidelines recommend feeding start at approximately 25% of the estimated goal, with advancement to goal over 35 days. ASPEN recommends fluid and electrolyte status be monitored as needed.50 The NICE guidelines recommend starting nutrition support at a maximum of 10 kcal/kg/d with slow increase to meet or exceed full needs by 47 days. For extremely malnourished patients (eg, BMI <14 kg/m2, or negligible intake for >15 days), they recommend starting at 5 kcal/kg/d. For patients at high risk of developing refeeding syndrome, the NICE guidelines recommend vitamin repletion immediately before and during the first 10 days of feeding (thiamine, vitamin B, and a balanced multivitamin/trace element supplement). Cardiac monitoring is recommended for this group as well as any patients who are at risk for cardiac arrhythmias. Careful monitoring of fluid balance and restoring circulatory volume is recommended, as is repletion of potassium, phosphate, and magnesium.56

TERMINATION OF THERAPY

Termination of nutrition support often involves transitioning from one mode of support to another. PN can be discontinued when oral or enteral intake reaches 60% of total calories; enteral intake can be discontinued when oral intake reaches the same level. However, the patient should be observed maintaining their intake; if they cannot, nutrition support should be resumed.12

TRANSITION OF CARE PLAN

Patients discharged from the hospital on enteral or parenteral nutrition require the support of a coordinated multidisciplinary team including dietitians, home nutrition delivery companies, primary care physicians trained in specialized nutrition support, community pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals, if indicated. These relationships should be established prior to discharge, with education about the patient's individualized nutrition plan, and training with the equipment and supplies.10, 56

CONCLUSION

This review provides an overview of managing the at‐risk or malnourished patient by describing the processes of screening, assessment, and development and implementation of a nutrition care plan in the acutely ill hospitalized patient. Malnutrition is a relatively common, yet underdiagnosed entity that impacts patient outcomes, length of stay, hospital costs, and readmissions. Acute illness in a patient already nutritionally debilitated by chronic disease may cause rapid depletion in nutritional stores. Hospitals are required to screen patients for malnutrition on admission and at regular intervals, and to develop and implement a nutrition care plan for those at risk. The plan guides how nutrition therapy is provided, monitored for adequacy and adverse effects, and assessed for achievement of nutritional goals. It encompasses the use of dietary modifications, and enteral and parenteral nutrition. Clinicians must be aware of serious but avoidable adverse effects, particularly refeeding syndrome in malnourished patients. Prior to discharge, the patient should have already been transitioned from EN or PN to taking adequate amounts of calories by mouth; otherwise, careful discharge planning to educate the patients and/or caregivers, and coordinate the necessary multidisciplinary community services is necessary.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to Ms Susan Lundy, for her helpful and timely information, and Ms Lisa Boucher, for her invaluable assistance with this manuscript and its submission.

Disclosures: Susan Brantley is on the Speaker's Bureau for Nestle Nutrition and for Abbott Nutrition. Authors Kirkland, Kashiwagi, Scheurer, and Varkey have nothing to report.

- ,,, et al.Prevalence of malnutrition on admission to four hospitals in England. The Malnutrition Prevalence Group.Clin Nutr.2000;19(3):191–195.

- ,.The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs evaluated through a multivariate model analysis.Clin Nutr.2003;22(3):235–239.

- ,,,.Malnutrition among hospitalized patients. A problem of physician awareness.Arch Intern Med.1987;147(8):1462–1465.

- ,,,,.Malnutrition is prevalent in hospitalized medical patients: are housestaff identifying the malnourished patient?Nutrition.2006;22(4):350–354.

- ,,, et al.Malnutrition in subacute care.Am J Clin Nutr.2002;75(2):308–313.

- ,,, et al.Malnutrition is an independent factor associated with nosocomial infections.Br J Nutr.2004;92(1):105–111.

- ,.Impact of body mass index on outcomes following critical care.Chest.2003;123(4):1202–1207.

- ,,, et al.EuroOOPS: an international, multicentre study to implement nutritional risk screening and evaluate clinical outcome.Clin Nutr.2008;27(3):340–349.

- ,,,,.Consensus statement: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition).J Parenter Enteral Nutr.2012;36(3):275–283.

- ,,, et al.Standards for nutrition support: adult hospitalized patients.Nutr Clin Pract.2010;25(4):403–414.

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.), Board of Directors and Clinical Practice Committee. Definition of Terms, Style, and Conventions used in A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors‐Approved Documents. May2012. Available at: http://www.nutritioncare.org/Library.aspx. Accessed June 29, 2012.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.Comprehensive Accreditation for Hospitals.Chicago, IL:Joint Commission on Accreditation for Healthcare Organizations;2007.

- ,.Nutrition screening and assessment. In: Gottschlich MM, ed.The ASPEN Nutrition Support Core Curriculum: A Case‐Based Approach—The Adult Patient.1st ed.Silver Spring, MD:American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition;2007:163–186.

- .Nutrition screening tools for hospitalized patients.Nutr Clin Pract.2008;23(4):373–382.

- .Nutrition screening and assessment. In: Skipper A, ed.Dietitian's Handbook of Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition.3rd ed.Sudbury, MA:Jones 2012:4–21.

- ,.Nutritional assessment in the hospitalized patient.Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care.2003;6(5):531–538.

- ,,,,.Nutritional and metabolic assessment of the hospitalized patient.J Parenter Enteral Nutr.1977;1(1):11–22.

- ,,.Hepatic proteins and nutrition assessment.J Am Diet Assoc.2004;104(8):1258–1264.

- .The albumin‐nutrition connection: separating myth from fact.Nutrition.2002;18(2):199–200.

- ,.Predictive equations for energy needs for the critically ill.Respir Care.2009;54(4):509–521.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines, guidelines, guidelines: what are we to do with all of these North American guidelines?J Parenter Enteral Nutr.2010;34(6):625–643.

- ,,, et al.Applied nutrition in ICU patients. A consensus statement of the American College of Chest Physicians.Chest.1997;111(3):769–778.

- ,,,,.Comparison of resting energy expenditure prediction methods with measured resting energy expenditure in obese, hospitalized adults.J Parenter Enteral Nutr.2009;33(2):168–175.

- ,,,,,.A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals.Am J Clin Nutr.1990;51(2):241–247.

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adult and pediatric patients.J Parenter Enteral Nutr.2002;26(suppl):1SA–138SA.

- ,,.American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition.Gastroenterology.1995;108(4):1282–1301.

- ,,, et al.ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition: intensive care.Clin Nutr.2006;25(2):210–223.

- ,.Nutritional support. In: Shojania KG, Duncan BW, McDonald KM, et al, eds.Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Number 43.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services, July2001. AHRQ Publication 01‐E058. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov.

- Veterans Affairs Total Parenteral Nutrition Cooperative Study Group.Perioperative total parenteral nutrition in surgical patients.N Engl J Med.1991;328(8):525–532.

- ,,,,.Does enteral nutrition affect clinical outcome? A systematic review of the randomized trials.Am J Gastroenterol.2007;102(2):412–429.

- ,,,.Nutrition in the stroke patient.Nutr Clin Pract.2011;26(3):242–252.

- ,,.Nutrition diagnosis and intervention. In: Mahan LK, Escott‐Stump S, eds.Krause's Food and Nutrition Therapy.12th ed.St Louis, MO:Saunders Elsevier;2008:454–469.

- Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS‐103s784es/pdf/BILLS‐103s784es.pdf. Accessed June 29,2012.

- .Intervention: dietary supplementation and integrative care. In: Mahan LK, Escott‐Stump S, eds.Krause's Food and Nutrition Therapy.12th ed.St Louis, MO:Saunders Elsevier;2008:470–474.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: executive summary.Crit Care Med.2009;37(5):1757–1761.

- ,,,,;for the. Canadian Critical Care Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee.Canadian clinical practice guidelines for nutrition support in mechanically ventilated, critically ill adult patients.J Parenter Enteral Nutr.2003;27(5):355–373.

- American Dietetic Association Evidence Library. Critical Illness. Available at: http://www.adaevidencelibrary.com/template.cfm?key=767115(5 suppl):64S–70S.

- .Enteral nutrition. In: Skipper A, ed.Dietitian's Handbook of Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition.3rd ed.Sudbury, MA:Jones 2012:259–280.

- .Enteral formula selection. In: Charney P, Malone A, eds.ADA Pocket Guide to Enteral Nutrition.Chicago, IL:American Dietetic Association;2006:63–122.

- ,.Overview of enteral nutrition. In: Gottschlich MM, ed.The ASPEN Nutrition Support Core Curriculum: A Case‐Based Approach—The Adult Patient.1st ed.Silver Spring, MD:American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition;2007:187–208.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.).J Parenter Enteral Nutr.2009;33(3):277–316.

- ,,,,,.ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: surgery.Clin Nutr.2009;28(4):378–386.

- ,,, et al.Safe practices for parenteral nutrition.J Parenter Enteral Nutr.2004;28(6):S39–S70.

- ,,,,,.Contribution of calories from propofol to total energy intake.J Am Diet Assoc.1995;95(9 supplement):A25.

- ,,,.Metabolic and thermogenic response to continuous and cyclic total parenteral nutrition in traumatised and infected patients.Clin Nutr.1994;13(5):291–301.

- ,,.The effect of abrupt cessation of total parenteral nutrition on serum glucose: a randomized trial.Am Surg.2000;66(9):866–869.

- ,,,,.The effect of acute discontinuation of total parenteral nutrition.Ann Surg.1986;204(5):524–529.

- ,,.Refeeding syndrome: what it is, and how to prevent and treat it.BMJ.2008;336(7659):1495–1498.

- ,,, et al.Enteral nutrition practice recommendations.J Parenter Enteral Nutr.2009;33(2):122–167.

- ,,.Control of diarrhea by fiber‐enriched diet in ICU patients on enteral nutrition: a prospective randomized controlled trial.Clin Nutr.2004;23(6):1344–1352.

- ,,,,,.Supine body position as a risk factor for nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients: a randomised trial.Lancet.1999;354(9193):1851–1858.

- .Parenteral nutrition in the critically ill patient.N Engl J Med.2009;361(11):1088–1097.

- ,,,.Refeeding syndrome: treatment considerations based on collective analysis of literature case reports.Nutrition.2010;26(2):156–167.

- ,,.Re‐feeding syndrome in head and neck cancer‐prevention and management.Oral Oncol.2011;47(9):792–796.

- Nutrition Support in Adults. NICE Clinical Guideline No. 32. 2006. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG32/NICEGuidance. Accessed November 29,2011.

- ,,.The importance of the refeeding syndrome.Nutrition.2001;17(7–8):632–637.

Malnutrition is present in 20% to 50% of hospitalized patients.1, 2 Despite simple, validated screening tools, malnutrition tends to be underdiagnosed.3, 4 Over 90% of elderly patients transitioning from an acute care hospital to a subacute care facility are either malnourished or at risk of malnutrition.5 Malnutrition has been associated with increased risk of nosocomial infections,6 worsened discharge functional status,7 and higher mortality,8 as well as longer lengths of stay7, 8 and higher hospital costs.2

Malnutrition describes either overnutrition or undernutrition that causes a change in body composition and decreased function.9 Malnutrition in hospitalized patients is typically related to undernutrition due to either reduced intake or increased metabolic rate. Reasons for reduced intake include poor appetite, reduced ability to chew or swallow, and nil per os (NPO) status. Patients with acute or chronic illnesses may either be malnourished on admission, or develop malnutrition within a few days of hospital admission, due to the effects of the inflammatory state on metabolism. Given that malnutrition is potentially modifiable, it is important to screen for malnutrition and, when present, develop, implement, and monitor a nutrition care plan10 (Figure 1).

The purpose of this review is to provide the hospitalist with an overview of screening, assessment, and development and implementation of a nutrition care plan in the acutely ill hospitalized patient.

PATIENT SCREENING

Nutrition screening identifies patients with nutritional deficits who may benefit from further detailed nutrition assessment and intervention.11 The Joint Commission requires that all patients admitted to acute care hospitals be screened for risk of malnutrition within 24 hours.12 Those considered at risk for malnutrition have significant weight changes, chronic disease or an acute inflammatory process, or have been unable to ingest adequate calories for 7 days.13

Those not at risk should be regularly rescreened throughout their hospital stay. The American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) recommends that institutions create and approve a screening process according to the patient population served.10 There are several tools validated for use in the acute care setting.14 Many institutions trigger an automatic nutrition consult when certain screening criteria are met.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

Nutrition assessment should be performed by a dietitian or nutrition consult provider in patients who screen at risk for malnutrition to characterize and determine the cause of nutritional deficits.10 The nutrition assessment identifies history and physical examination elements to diagnose malnutrition. An ASPEN consensus statement recommends the diagnosis of malnutrition if 2 or more of the following are present: insufficient energy intake, weight loss, loss of muscle mass, loss of subcutaneous fat, localized or generalized fluid accumulation, and decreased functional status measured by hand‐grip strength.9 The nutrition assessment should also consider how long the patient has been without adequate nutrition, document baseline nutrition parameters,15 and estimate caloric requirements to determine nutrition support therapy needs.10 Nutrition assessment typically includes the following components.

History

A careful history elicits the majority of information needed to determine the cause and severity of malnutrition.16 Patients should be questioned about a typical day's oral intake prior to hospitalization, and about factors that affect their intake such as sensory deficits, fine motor dysfunction, or chewing and swallowing difficulties, which often decline in chronically ill and elderly patients. Nutrition may be affected by financial difficulties or limited social support, and access to food should be assessed.

Physical Findings

Weight loss is the best physical exam predictor of malnutrition risk, although nutritional depletion can occur in a very short time in acutely ill or injured patients before substantial weight loss has occurred. The likelihood of malnutrition is increased if a patient has: a body mass index (BMI) <18.5 kg/m2; unintentional loss of >2.3 kg (5 lb) or 5% of body weight over 1 month; and unintentional loss of >4.5 kg (10 lb) or 10% of body weight over 6 months.17 Weight loss may be masked by fluid retention from chronic conditions, such as heart failure, or from volume resuscitation in the acutely ill patient.9, 16

Body mass index can be misleading, as age‐related height loss may artificially increase BMI, and height may be difficult to accurately measure in a kyphotic, unsteady, or bedridden patient. The clinician may find evidence of loss of subcutaneous fat or muscle mass in patients with chronic illness, but these findings may not be evident in the acutely ill patient.9 Other physical exam assessments of malnutrition, such as arm span, skinfold thickness, and arm circumference are not reliable.16

Laboratory Tests

Biochemical markers, including transferrin, albumin, and prealbumin, have not been proven as accurate predictors of nutrition status because they may change as a result of other factors not related to nutrition.15, 18 Serum albumin, for example, may be more reflective of the degree of metabolic stress.19 Prealbumin has a serum half‐life much shorter than albumin or transferrin (approximately 2448 hours) and is perhaps the most useful protein marker to assess the adequacy of nutritional replacement after the inflammatory state is resolved.18

Calculating Caloric Requirements

Energy expenditure measurement is considered the gold standard to determine patients' caloric needs. Actual measurement by methods such as indirect calorimetry, which measures oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production, and calculates energy expenditure, is challenging in everyday clinical settings. Predictive equations often are used as alternative methods to estimate patients' caloric requirements.20 There is no consensus among the 3 North American societies' guidelines (the Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines; the American Dietetics Association's evidence‐based guideline for critical illness; and the Society of Critical Care Medicine and American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition's joint guideline) as to the best method.21

In the simplest equation, caloric needs are estimated by calories per kilogram.22 In obese patients, using actual body weight will overestimate needs, but using ideal body weight may cause underfeeding. A small study comparing predictive equations in obese hospitalized patients found the Harris‐Benedict equations (H‐BE) using adjusted body weight and a stress factor to be most accurate, but only in 50% of patients.23 Most clinicians are familiar with the H‐BE, but alternatives such as calories per kilogram or the Mifflin St.‐Jeor equation24 are often used (S. Brantley (May 5, 2012), S. Lundy (May 23, 2012), personal communication).

Indications for Nutritional Intervention

In adults without preexisting malnutrition, inadequate nutritional intake for approximately 714 days should prompt nutritional intervention.25, 26 This timeline should be shorter (37 days) in those with lower energy reserves (eg, underweight or recent weight loss) or significant catabolic stress (eg, acutely ill patients).27, 28 Other patient populations shown to benefit from nutritional intervention include: postoperative patients who are anticipated to be NPO for more than 7 days or to be taking less than 60% of estimated caloric needs by postoperative day 10; preoperative patients with severe malnutrition29; those with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing elective surgery30; and stroke patients with persistent dysphagia for more than 7 days.31

DEVELOPMENT OF A NUTRITION CARE PLAN

The formal nutrition assessment of the at‐risk patient derives the information needed for the development of a nutrition care plan. This plan guides the provision of nutrition therapy, the intervention, the monitoring protocols, evaluation, and reassessment of nutrition goals or termination of specialized nutrition support.10 Assessments for adequacy of nutritional repletion are best done by repeated screening and physical examinations.18

IMPLEMENTATION OF NUTRITION CARE PLAN

Nutritional interventions include dietary modifications, enteral nutrition, and parenteral nutrition.

Dietary Modifications

The purpose of the diet is to provide the necessary nutrients to the body in a well‐tolerated form. Diets can be modified to provide for individual requirements, personal eating patterns and food preferences, and disease process and digestive capacity. Dietary adjustments include change in consistency of foods (eg, pureed, mechanical soft), increase or decrease in energy value, increase or decrease in the type of food or nutrient consumed (eg, sodium restriction, fiber enhancement), elimination of specific foods (eg, gluten‐free diet), adjustment in protein, fat, and carbohydrate content (eg, ketogenic diet, renal diet, cholesterol‐lowering diet), and adjustment of the number and frequency of meals.32

Dietary supplementation (eg, Boost, Ensure) is common practice in persons diagnosed with such conditions as cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Supplements enhance the diet by increasing the total daily intake of a vitamin, a mineral, an amino acid, an herb or other botanical33, and should not be used as a meal substitute.34 These supplements are varied in content of calories, protein, vitamins, and minerals. Various flavors and consistencies are also available. Several oral supplements are reviewed in Table 1.

| Oral Supplement* (Serving Size; mL) | Kcal/svg | Protein (g/svg) | Fat (g/svg) | CHO (g/svg) | Na (mg/svg) | K (mg/svg) | Ca (mg/svg) | Phos (mg/svg) | Mg (mg/svg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Boost Original (237) | 240 | 10 | 4 | 41 | 150 | 460 | 300 | 300 | 100 |

| Ensure Nutrition Shake (237) | 250 | 9 | 6 | 40 | 200 | 370 | 300 | 250 | 100 |

| Carnation Instant Breakfast Ready to Drink (325) | 250 | 14 | 5 | 34 | 180 | 330 | 500 | 500 | 120 |

| Resource Breeze (fruit‐flavored) clear liquid (237) | 250 | 9 | 0 | 54 | 80 | 10 | 10 | 150 | 1 |

| Glucerna 1.0 Ready to Drink low‐CHO (237) | 240 | 10 | 13 | 23 | 220 | 370 | 170 | 170 | 67 |

| Re/Gen low K and Phos (180) | 375 | 12 | 17 | 47 | 180 | 23 | 15 | 68 | 3 |

Enteral Nutrition

Enteral nutrition (EN) support should be provided to patients who have functioning gastrointestinal (GI) tracts but are unable to take adequate calories orally. Compared to parenteral nutrition (PN), EN is associated with favorable improvements in inflammatory cytokines, acute phase proteins, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, nosocomial infections, mortality, and cost.35 Enteral feeds are more physiologic than parenteral feeds, maintain GI structure and integrity, and avoid intravenous (IV) access complications. Patients with normal nutritional status on admission who require EN should be receiving over 50% of their caloric needs within the first week of hospital stay.25 Malnourished patients should reach this minimum goal within 35 days of admission.27, 28 EN is not contraindicated in the absence of bowel sounds or in the presence of increased gastric residuals.35 Withholding enteral feedings for gastric residual volumes <250 mL36, 37 or reduced bowel sounds can result in inadequate caloric intake or inappropriate use of PN.27

Gastric feedings are more physiologic than small bowel feedings, can be given by bolus or continuous infusion, and can be given by tubes that are easy to place at the bedside. Post‐pyloric feedings (nasoduodenal or nasojejunal) may be associated with a lower risk of pneumonia, and should be considered in high‐risk patients such as those receiving continuous sedatives or neuromuscular blockers.36 Post‐pyloric tube placement usually requires endoscopy, fluoroscopy, or electromagnetic guidance. Percutaneous feeding tubes (gastrostomy or jejunostomy) should be considered in those who require tube feedings for longer than 30 days.38

Assessment of patient requirements and disease state, as well as extensive knowledge of available formulas, is important in the selection of the appropriate enteral formula.39 Standardized formulas are used for most patients. The provision of adequate water must be considered with these formulas, particularly in the long‐term care and home settings.40 Many specialized formulas are designed for a particular disease state or condition, some of which are further reviewed in Table 2.

| Formula | Kcal/mL | Protein (g/L) | Fat (g/L) | CHO (g/L) | Osmolality (mOsm/kg H2O) | Na (mEq/L) | K (mEq/L) | Ca (mg/L) | Mg (mg/L) | Phos (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| Nutren 1.0‐low residue | 1 | 40 | 38 | 127 | 315 | 38 | 32 | 668 | 268 | 668 |

| Osmolite 1.0 Cal low residue | 1 | 44.3 | 34.7 | 143.9 | 300 | 40.4 | 40.2 | 760 | 305 | 1760 |

| Replete high protein, low residue | 1 | 62.4 | 34 | 112 | 300 | 38.1 | 38.5 | 1000 | 400 | 1000 |

| Replete Fiber high protein with fiber | 1 | 62.4 | 34 | 112 | 310 | 38.1 | 38.5 | 1000 | 400 | 1000 |

| Osmolite 1.5 low residue, calorically dense | 1.5 | 62.7 | 49.1 | 203.6 | 525 | 60.9 | 46 | 1000 | 400 | 1000 |

| Two Cal calorie and protein dense | 2 | 83.5 | 91 | 219 | 725 | 64 | 63 | 1050 | 425 | 1050 |

| Vivonex RTF‐elemental | 1 | 50 | 11.6 | 176 | 630 | 30.4 | 31 | 668 | 268 | 668 |

| Nepro with Carb Steady‐for electrolyte, fluid restriction (eg, dialysis) | 1.8 | 81 | 96 | 161 | 745 | 46 | 27 | 1060 | 210 | 720 |

| Nutren Glytrol low CHO | 1 | 45.2 | 47.6 | 100 | 280 | 32.2 | 35.9 | 720 | 286 | 720 |

| NutriHep‐for hepatic disease | 1.5 | 40 | 21.2 | 290 | 790 | 160 | 33.9 | 956 | 376 | 1000 |

If concerned about formula tolerance, one solution is to initiate the formula at a low rate and increase to the goal rate over 2448 hours. Dilution of enteral formulas is not necessary to assure optimal tolerance. Continuous feedings are recommended for most patients initially and after tolerance has been established, bolus feedings can be attempted if the feeding tube terminates in the stomach. Bolus feedings, where 240480 mL of formula are delivered through a syringe over 1015 minutes, may be more physiological for patients. This regimen can be repeated 46 times daily to meet nutrition goals.41

Parenteral Nutrition

PN provides macronutrients such as carbohydrates, protein, and fat; micronutrients such as vitamins, minerals, electrolytes, and trace elements are added in appropriate concentrations. PN may also provide the patient's daily fluid needs. The timing of PN initiation depends upon the patient's initial nutritional status. ASPEN does not recommend PN during the first 7 days of hospitalization in critically ill patients with normal nutritional status. If the patient is not receiving 100% of caloric needs from EN after 7 days, supplemental PN should be considered. However, if on admission a patient is already malnourished and EN is not feasible, PN should be initiated and continued until the patient is receiving at least 60% of caloric needs by enteral route.42 This includes patients with intestinal obstruction, ileus, peritonitis, malabsorption, high output enterocutaneous fistulae, intestinal ischemia, intractable vomiting and diarrhea, severe shock, and fulminant sepsis.10, 43

Standardized commercial PN products are available and reduce the number of steps required between ordering and administration, as compared to customized PN, which is compounded for a particular patient. However, despite improved efficiency and lower cost, there is no evidence that standardized preparations are safer to patients than customized solutions. Institutions utilizing standardized PN must also have a mechanism to customize formulas for those with complex needs.44

Creating a customized parenteral solution involves several basic steps. Total caloric requirement may be estimated using a predictive formula, as previously discussed; calories/kg of ideal body weight is the simplest method. Most hospitalized patients require 2030 calories/kg/d. Daily fluid requirement may be based on kilocalories (kcal) delivered, or by ideal body weight (eg, 1 mL/kcal or 3040 mL/kg). More fluid may be needed in patients with significant sensible or insensible losses; those with renal failure or heart failure should receive less fluid.

Protein needs are calculated by multiplying ideal body weight (kg) by estimated protein needs in g/kg/d (1.22 g/kg/d for catabolic patients). Protein should provide approximately 20% of total calories. Protein restriction is not required in renal impairment; acutely ill patients on renal replacement therapy should receive 1.51.8 g/kg/d. In hepatic failure patients, protein should be restricted only if hepatic encephalopathy fails to improve with other measures.

Knowing the protein, kcal, and fluid needs of the patient, the practitioner divides the remaining non‐protein calories between carbohydrates and fat. Approximately 70%85% of non‐protein calories should be provided as carbohydrates (dextrose), up to 7 g/kg/d. The other 15%30% are as fat, in lipid solutions, providing a maximum of 2.5 g/kg/d. Lipid solutions are provided as either 10% (1.1 kcal/mL) or 20% (2.2 kcal/mL) concentrations.43, 44 Propofol's contribution to fat intake complicates estimating total fat intake in critically ill patients.45

Standardized parenteral multivitamin preparations are available; the clinician must determine if preparations containing vitamin K are appropriate. Of the trace elements, copper and manganese should be restricted in hepatobiliary disease.44

Acutely ill patients receive PN as a 24‐hour infusion, to minimize its impact on volume status and energy expenditure,46 providing 50% of needs on infusion day one and reaching goal within 4872 hours, rather than cyclic infusions over shorter intervals. Daily assessments of vital signs, intake and output, and weight are necessary to monitor volume status.

Once a patient is taking at least 60% of caloric needs either by mouth or by EN, PN can be discontinued. Tapering the infusion is not required, as abrupt discontinuation has not been demonstrated to cause symptomatic hypoglycemia.47, 48

PATIENT MONITORING

Laboratory monitoring with nutrition support should include baseline electrolytes, glucose, renal function, coagulation studies, triglycerides, magnesium, phosphorus, cholesterol, platelet count, and hepatobiliary enzymes. Electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus should be checked daily for 3 days and, if normal, should then be checked biweekly. Capillary glucose should be monitored several times a day until stable. Weekly triglycerides, albumin, cholesterol, coagulation studies, and liver enzymes should also be checked in patients while on parenteral nutrition.25 Patients at risk for refeeding syndrome should have potassium, phosphate, calcium, and magnesium measured daily for 7 days, with repletion as necessary. These electrolytes should be monitored 3 times the following week if stable.49

Patients should be monitored clinically for gastrointestinal tolerance of enteral nutrition. All 3 North American guidelines recommend monitoring gastric residual volumes (GRV); however, there is no consensus on the volume considered to require intervention. Motility agents are recommended as first line treatment of high GRV.36, 37, 42 If high GRV continues, tube feeding should be held, and tube placement, medications, and metabolic assessment should be reviewed. Placement of a transpyloric feeding tube may be indicated.50

Adverse Effects and Complications of Nutrition Support

Regarding EN, complications include those related to tube placement and maintenance, infections, and medical complications of the feeds themselves. Some of the adverse effects of the enteral formulas may be attenuated. Diarrhea, which occurs in up to 20% of patients, may be avoided with slow feed advancement, use of low‐osmotic formulas, or fiber additives.51 Gastric distention and abdominal pain may improve with slow feed advancement and continuous (rather than bolus) feeds. Small‐bore tubes and acid‐reducing medications may decrease gastroesophageal reflux, and aspiration pneumonia may be avoided by semi‐recumbent positioning and post‐pyloric feeding.52

Complications of PN may be grouped as mechanical, infectious, and metabolic. The mechanical complications of central line placement include pneumothorax, arterial puncture, hematoma, air embolism, and line malpositioning. Catheter‐related deep venous thrombosis may occur. Patients on PN through a central line are at risk for central line‐associated bloodstream infections.25 The metabolic complications such as hyperglycemia, electrolyte disorders, hepatic steatosis, and volume overload may have severe consequences, such as heart failure or neuromuscular dysfunction, thus they require close attention.53

A complication of nutrition support that may occur regardless of route is the refeeding syndrome. Refeeding syndrome describes fluid shifts and electrolyte abnormalities that occur after initiation of oral, enteral, or parenteral nutrition in a malnourished or starved patient.54, 55 There are no formal criteria for diagnosing refeeding syndrome.

In the starved state, the body switches from carbohydrate to protein and fat metabolism. Reintroduction of carbohydrates stimulates insulin release with glycogen, fat, and protein synthesis. Associated uptake of glucose, potassium, magnesium, phosphate, and water into cells causes electrolyte and fluid abnormalities. Although hypophosphatemia is the hallmark of refeeding syndrome, it is not pathognomonic. Additional disturbances include hypokalemia, hyperglycemia, hypomagnesemia, thiamine deficiency, and fluid imbalance.49 Patients at risk of refeeding should have serum electrolytes, magnesium, phosphorus, and glucose checked before nutrition support starts. The degree of laboratory abnormalities, if any, and the clinical course of refeeding guides the frequency of subsequent blood tests.56 These consequences of refeeding can adversely affect every major organ system and may result in death.57

Starvation physiology underlies all risk factors for refeeding syndrome. In hospitalized patients, those at risk for refeeding include, but are not limited to, the elderly, oncology patients, postoperative patients, alcohol‐dependent patients, those with malabsorptive states, those who are fasting or chronically malnourished, and those on diuretic therapy.54, 57 The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) of England and Wales has published criteria to identify patients at high risk for refeeding (Table 3).56 Identification of at‐risk patients and attention to their nutritional needs prevents refeeding syndrome.

|

| Patient has 1 or more of the following: |

| BMI <16 kg/m2 |

| Unintentional weight loss >15% within the last 36 mo |

| Little or no nutritional intake for more than 10 d |

| Low levels of potassium, phosphate, or magnesium prior to feeding |

| Or patient has 2 or more of the following: |

| BMI <18.5 kg/m2 |

| Unintentional weight loss >10% within the last 36 mo |

| Little or no nutritional intake for more than 5 d |

| A history of alcohol abuse or drugs including insulin, chemotherapy, antacids, or diuretics |

ASPEN and NICE have each issued guidelines for initiating nutrition support in patients at risk for refeeding. ASPEN guidelines recommend feeding start at approximately 25% of the estimated goal, with advancement to goal over 35 days. ASPEN recommends fluid and electrolyte status be monitored as needed.50 The NICE guidelines recommend starting nutrition support at a maximum of 10 kcal/kg/d with slow increase to meet or exceed full needs by 47 days. For extremely malnourished patients (eg, BMI <14 kg/m2, or negligible intake for >15 days), they recommend starting at 5 kcal/kg/d. For patients at high risk of developing refeeding syndrome, the NICE guidelines recommend vitamin repletion immediately before and during the first 10 days of feeding (thiamine, vitamin B, and a balanced multivitamin/trace element supplement). Cardiac monitoring is recommended for this group as well as any patients who are at risk for cardiac arrhythmias. Careful monitoring of fluid balance and restoring circulatory volume is recommended, as is repletion of potassium, phosphate, and magnesium.56

TERMINATION OF THERAPY

Termination of nutrition support often involves transitioning from one mode of support to another. PN can be discontinued when oral or enteral intake reaches 60% of total calories; enteral intake can be discontinued when oral intake reaches the same level. However, the patient should be observed maintaining their intake; if they cannot, nutrition support should be resumed.12

TRANSITION OF CARE PLAN

Patients discharged from the hospital on enteral or parenteral nutrition require the support of a coordinated multidisciplinary team including dietitians, home nutrition delivery companies, primary care physicians trained in specialized nutrition support, community pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals, if indicated. These relationships should be established prior to discharge, with education about the patient's individualized nutrition plan, and training with the equipment and supplies.10, 56

CONCLUSION

This review provides an overview of managing the at‐risk or malnourished patient by describing the processes of screening, assessment, and development and implementation of a nutrition care plan in the acutely ill hospitalized patient. Malnutrition is a relatively common, yet underdiagnosed entity that impacts patient outcomes, length of stay, hospital costs, and readmissions. Acute illness in a patient already nutritionally debilitated by chronic disease may cause rapid depletion in nutritional stores. Hospitals are required to screen patients for malnutrition on admission and at regular intervals, and to develop and implement a nutrition care plan for those at risk. The plan guides how nutrition therapy is provided, monitored for adequacy and adverse effects, and assessed for achievement of nutritional goals. It encompasses the use of dietary modifications, and enteral and parenteral nutrition. Clinicians must be aware of serious but avoidable adverse effects, particularly refeeding syndrome in malnourished patients. Prior to discharge, the patient should have already been transitioned from EN or PN to taking adequate amounts of calories by mouth; otherwise, careful discharge planning to educate the patients and/or caregivers, and coordinate the necessary multidisciplinary community services is necessary.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to Ms Susan Lundy, for her helpful and timely information, and Ms Lisa Boucher, for her invaluable assistance with this manuscript and its submission.

Disclosures: Susan Brantley is on the Speaker's Bureau for Nestle Nutrition and for Abbott Nutrition. Authors Kirkland, Kashiwagi, Scheurer, and Varkey have nothing to report.

Malnutrition is present in 20% to 50% of hospitalized patients.1, 2 Despite simple, validated screening tools, malnutrition tends to be underdiagnosed.3, 4 Over 90% of elderly patients transitioning from an acute care hospital to a subacute care facility are either malnourished or at risk of malnutrition.5 Malnutrition has been associated with increased risk of nosocomial infections,6 worsened discharge functional status,7 and higher mortality,8 as well as longer lengths of stay7, 8 and higher hospital costs.2

Malnutrition describes either overnutrition or undernutrition that causes a change in body composition and decreased function.9 Malnutrition in hospitalized patients is typically related to undernutrition due to either reduced intake or increased metabolic rate. Reasons for reduced intake include poor appetite, reduced ability to chew or swallow, and nil per os (NPO) status. Patients with acute or chronic illnesses may either be malnourished on admission, or develop malnutrition within a few days of hospital admission, due to the effects of the inflammatory state on metabolism. Given that malnutrition is potentially modifiable, it is important to screen for malnutrition and, when present, develop, implement, and monitor a nutrition care plan10 (Figure 1).

The purpose of this review is to provide the hospitalist with an overview of screening, assessment, and development and implementation of a nutrition care plan in the acutely ill hospitalized patient.

PATIENT SCREENING

Nutrition screening identifies patients with nutritional deficits who may benefit from further detailed nutrition assessment and intervention.11 The Joint Commission requires that all patients admitted to acute care hospitals be screened for risk of malnutrition within 24 hours.12 Those considered at risk for malnutrition have significant weight changes, chronic disease or an acute inflammatory process, or have been unable to ingest adequate calories for 7 days.13

Those not at risk should be regularly rescreened throughout their hospital stay. The American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) recommends that institutions create and approve a screening process according to the patient population served.10 There are several tools validated for use in the acute care setting.14 Many institutions trigger an automatic nutrition consult when certain screening criteria are met.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

Nutrition assessment should be performed by a dietitian or nutrition consult provider in patients who screen at risk for malnutrition to characterize and determine the cause of nutritional deficits.10 The nutrition assessment identifies history and physical examination elements to diagnose malnutrition. An ASPEN consensus statement recommends the diagnosis of malnutrition if 2 or more of the following are present: insufficient energy intake, weight loss, loss of muscle mass, loss of subcutaneous fat, localized or generalized fluid accumulation, and decreased functional status measured by hand‐grip strength.9 The nutrition assessment should also consider how long the patient has been without adequate nutrition, document baseline nutrition parameters,15 and estimate caloric requirements to determine nutrition support therapy needs.10 Nutrition assessment typically includes the following components.

History

A careful history elicits the majority of information needed to determine the cause and severity of malnutrition.16 Patients should be questioned about a typical day's oral intake prior to hospitalization, and about factors that affect their intake such as sensory deficits, fine motor dysfunction, or chewing and swallowing difficulties, which often decline in chronically ill and elderly patients. Nutrition may be affected by financial difficulties or limited social support, and access to food should be assessed.

Physical Findings

Weight loss is the best physical exam predictor of malnutrition risk, although nutritional depletion can occur in a very short time in acutely ill or injured patients before substantial weight loss has occurred. The likelihood of malnutrition is increased if a patient has: a body mass index (BMI) <18.5 kg/m2; unintentional loss of >2.3 kg (5 lb) or 5% of body weight over 1 month; and unintentional loss of >4.5 kg (10 lb) or 10% of body weight over 6 months.17 Weight loss may be masked by fluid retention from chronic conditions, such as heart failure, or from volume resuscitation in the acutely ill patient.9, 16

Body mass index can be misleading, as age‐related height loss may artificially increase BMI, and height may be difficult to accurately measure in a kyphotic, unsteady, or bedridden patient. The clinician may find evidence of loss of subcutaneous fat or muscle mass in patients with chronic illness, but these findings may not be evident in the acutely ill patient.9 Other physical exam assessments of malnutrition, such as arm span, skinfold thickness, and arm circumference are not reliable.16

Laboratory Tests

Biochemical markers, including transferrin, albumin, and prealbumin, have not been proven as accurate predictors of nutrition status because they may change as a result of other factors not related to nutrition.15, 18 Serum albumin, for example, may be more reflective of the degree of metabolic stress.19 Prealbumin has a serum half‐life much shorter than albumin or transferrin (approximately 2448 hours) and is perhaps the most useful protein marker to assess the adequacy of nutritional replacement after the inflammatory state is resolved.18

Calculating Caloric Requirements

Energy expenditure measurement is considered the gold standard to determine patients' caloric needs. Actual measurement by methods such as indirect calorimetry, which measures oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production, and calculates energy expenditure, is challenging in everyday clinical settings. Predictive equations often are used as alternative methods to estimate patients' caloric requirements.20 There is no consensus among the 3 North American societies' guidelines (the Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines; the American Dietetics Association's evidence‐based guideline for critical illness; and the Society of Critical Care Medicine and American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition's joint guideline) as to the best method.21

In the simplest equation, caloric needs are estimated by calories per kilogram.22 In obese patients, using actual body weight will overestimate needs, but using ideal body weight may cause underfeeding. A small study comparing predictive equations in obese hospitalized patients found the Harris‐Benedict equations (H‐BE) using adjusted body weight and a stress factor to be most accurate, but only in 50% of patients.23 Most clinicians are familiar with the H‐BE, but alternatives such as calories per kilogram or the Mifflin St.‐Jeor equation24 are often used (S. Brantley (May 5, 2012), S. Lundy (May 23, 2012), personal communication).

Indications for Nutritional Intervention

In adults without preexisting malnutrition, inadequate nutritional intake for approximately 714 days should prompt nutritional intervention.25, 26 This timeline should be shorter (37 days) in those with lower energy reserves (eg, underweight or recent weight loss) or significant catabolic stress (eg, acutely ill patients).27, 28 Other patient populations shown to benefit from nutritional intervention include: postoperative patients who are anticipated to be NPO for more than 7 days or to be taking less than 60% of estimated caloric needs by postoperative day 10; preoperative patients with severe malnutrition29; those with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing elective surgery30; and stroke patients with persistent dysphagia for more than 7 days.31

DEVELOPMENT OF A NUTRITION CARE PLAN

The formal nutrition assessment of the at‐risk patient derives the information needed for the development of a nutrition care plan. This plan guides the provision of nutrition therapy, the intervention, the monitoring protocols, evaluation, and reassessment of nutrition goals or termination of specialized nutrition support.10 Assessments for adequacy of nutritional repletion are best done by repeated screening and physical examinations.18

IMPLEMENTATION OF NUTRITION CARE PLAN

Nutritional interventions include dietary modifications, enteral nutrition, and parenteral nutrition.

Dietary Modifications

The purpose of the diet is to provide the necessary nutrients to the body in a well‐tolerated form. Diets can be modified to provide for individual requirements, personal eating patterns and food preferences, and disease process and digestive capacity. Dietary adjustments include change in consistency of foods (eg, pureed, mechanical soft), increase or decrease in energy value, increase or decrease in the type of food or nutrient consumed (eg, sodium restriction, fiber enhancement), elimination of specific foods (eg, gluten‐free diet), adjustment in protein, fat, and carbohydrate content (eg, ketogenic diet, renal diet, cholesterol‐lowering diet), and adjustment of the number and frequency of meals.32

Dietary supplementation (eg, Boost, Ensure) is common practice in persons diagnosed with such conditions as cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Supplements enhance the diet by increasing the total daily intake of a vitamin, a mineral, an amino acid, an herb or other botanical33, and should not be used as a meal substitute.34 These supplements are varied in content of calories, protein, vitamins, and minerals. Various flavors and consistencies are also available. Several oral supplements are reviewed in Table 1.

| Oral Supplement* (Serving Size; mL) | Kcal/svg | Protein (g/svg) | Fat (g/svg) | CHO (g/svg) | Na (mg/svg) | K (mg/svg) | Ca (mg/svg) | Phos (mg/svg) | Mg (mg/svg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Boost Original (237) | 240 | 10 | 4 | 41 | 150 | 460 | 300 | 300 | 100 |

| Ensure Nutrition Shake (237) | 250 | 9 | 6 | 40 | 200 | 370 | 300 | 250 | 100 |

| Carnation Instant Breakfast Ready to Drink (325) | 250 | 14 | 5 | 34 | 180 | 330 | 500 | 500 | 120 |

| Resource Breeze (fruit‐flavored) clear liquid (237) | 250 | 9 | 0 | 54 | 80 | 10 | 10 | 150 | 1 |

| Glucerna 1.0 Ready to Drink low‐CHO (237) | 240 | 10 | 13 | 23 | 220 | 370 | 170 | 170 | 67 |

| Re/Gen low K and Phos (180) | 375 | 12 | 17 | 47 | 180 | 23 | 15 | 68 | 3 |

Enteral Nutrition

Enteral nutrition (EN) support should be provided to patients who have functioning gastrointestinal (GI) tracts but are unable to take adequate calories orally. Compared to parenteral nutrition (PN), EN is associated with favorable improvements in inflammatory cytokines, acute phase proteins, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, nosocomial infections, mortality, and cost.35 Enteral feeds are more physiologic than parenteral feeds, maintain GI structure and integrity, and avoid intravenous (IV) access complications. Patients with normal nutritional status on admission who require EN should be receiving over 50% of their caloric needs within the first week of hospital stay.25 Malnourished patients should reach this minimum goal within 35 days of admission.27, 28 EN is not contraindicated in the absence of bowel sounds or in the presence of increased gastric residuals.35 Withholding enteral feedings for gastric residual volumes <250 mL36, 37 or reduced bowel sounds can result in inadequate caloric intake or inappropriate use of PN.27

Gastric feedings are more physiologic than small bowel feedings, can be given by bolus or continuous infusion, and can be given by tubes that are easy to place at the bedside. Post‐pyloric feedings (nasoduodenal or nasojejunal) may be associated with a lower risk of pneumonia, and should be considered in high‐risk patients such as those receiving continuous sedatives or neuromuscular blockers.36 Post‐pyloric tube placement usually requires endoscopy, fluoroscopy, or electromagnetic guidance. Percutaneous feeding tubes (gastrostomy or jejunostomy) should be considered in those who require tube feedings for longer than 30 days.38

Assessment of patient requirements and disease state, as well as extensive knowledge of available formulas, is important in the selection of the appropriate enteral formula.39 Standardized formulas are used for most patients. The provision of adequate water must be considered with these formulas, particularly in the long‐term care and home settings.40 Many specialized formulas are designed for a particular disease state or condition, some of which are further reviewed in Table 2.

| Formula | Kcal/mL | Protein (g/L) | Fat (g/L) | CHO (g/L) | Osmolality (mOsm/kg H2O) | Na (mEq/L) | K (mEq/L) | Ca (mg/L) | Mg (mg/L) | Phos (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| Nutren 1.0‐low residue | 1 | 40 | 38 | 127 | 315 | 38 | 32 | 668 | 268 | 668 |

| Osmolite 1.0 Cal low residue | 1 | 44.3 | 34.7 | 143.9 | 300 | 40.4 | 40.2 | 760 | 305 | 1760 |

| Replete high protein, low residue | 1 | 62.4 | 34 | 112 | 300 | 38.1 | 38.5 | 1000 | 400 | 1000 |

| Replete Fiber high protein with fiber | 1 | 62.4 | 34 | 112 | 310 | 38.1 | 38.5 | 1000 | 400 | 1000 |

| Osmolite 1.5 low residue, calorically dense | 1.5 | 62.7 | 49.1 | 203.6 | 525 | 60.9 | 46 | 1000 | 400 | 1000 |

| Two Cal calorie and protein dense | 2 | 83.5 | 91 | 219 | 725 | 64 | 63 | 1050 | 425 | 1050 |

| Vivonex RTF‐elemental | 1 | 50 | 11.6 | 176 | 630 | 30.4 | 31 | 668 | 268 | 668 |

| Nepro with Carb Steady‐for electrolyte, fluid restriction (eg, dialysis) | 1.8 | 81 | 96 | 161 | 745 | 46 | 27 | 1060 | 210 | 720 |

| Nutren Glytrol low CHO | 1 | 45.2 | 47.6 | 100 | 280 | 32.2 | 35.9 | 720 | 286 | 720 |

| NutriHep‐for hepatic disease | 1.5 | 40 | 21.2 | 290 | 790 | 160 | 33.9 | 956 | 376 | 1000 |

If concerned about formula tolerance, one solution is to initiate the formula at a low rate and increase to the goal rate over 2448 hours. Dilution of enteral formulas is not necessary to assure optimal tolerance. Continuous feedings are recommended for most patients initially and after tolerance has been established, bolus feedings can be attempted if the feeding tube terminates in the stomach. Bolus feedings, where 240480 mL of formula are delivered through a syringe over 1015 minutes, may be more physiological for patients. This regimen can be repeated 46 times daily to meet nutrition goals.41

Parenteral Nutrition

PN provides macronutrients such as carbohydrates, protein, and fat; micronutrients such as vitamins, minerals, electrolytes, and trace elements are added in appropriate concentrations. PN may also provide the patient's daily fluid needs. The timing of PN initiation depends upon the patient's initial nutritional status. ASPEN does not recommend PN during the first 7 days of hospitalization in critically ill patients with normal nutritional status. If the patient is not receiving 100% of caloric needs from EN after 7 days, supplemental PN should be considered. However, if on admission a patient is already malnourished and EN is not feasible, PN should be initiated and continued until the patient is receiving at least 60% of caloric needs by enteral route.42 This includes patients with intestinal obstruction, ileus, peritonitis, malabsorption, high output enterocutaneous fistulae, intestinal ischemia, intractable vomiting and diarrhea, severe shock, and fulminant sepsis.10, 43