User login

Space Heater–Induced Bullous Erythema Ab Igne

To the Editor:

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a reticular erythematous hyperpigmentation of skin repeatedly exposed to moderate heat.1 It usually is asymptomatic, though some patients report itching or burning at the site.2 Historically caused by exposure to coal stoves or open fires, EAI has become increasingly common among individuals using space heaters, heating pads, or laptop computers near bare skin.2,3 Although EAI itself is benign and usually resolves with the removal of the exposure, it remains of clinical importance because of its association with underlying chronic disease, as chronic pain often is managed with frequent heating pad or hot water bottle use.2 Additionally, accurate diagnosis is important given the future risk for malignancy, as chronic changes of EAI have been reported to lead to squamous cell carcinoma or rarely Merkel cell carcinoma.2 Erythema ab igne is not traditionally associated with the formation of bullae; however, we present a case of bullous EAI that we believe highlights the importance of including this condition in the differential diagnosis of bullous disorders.

A 55-year-old man was admitted for presumed cellulitis of the bilateral legs. The patient had developed hyperpigmented discoloration of the medial surface of both legs with subsequent formation of tense bullae over the last 2 months. The dermatology department was consulted, as there was concern for bullous pemphigoid. The patient’s medical history was notable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diet-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis C virus with cirrhosis. The patient denied pruritus, pain, or known exposure of the legs to potential irritants prior to developing the lesions; however, with additional questioning he did report frequently sitting in front of a space heater with bare legs. Physical examination revealed multiple areas of reticulated erythematous hyperpigmentation with several overlying bullae (Figure 1). Many of the bullae were unroofed with full-thickness ulceration. Biopsies were taken for hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2) and direct immunofluorescence.

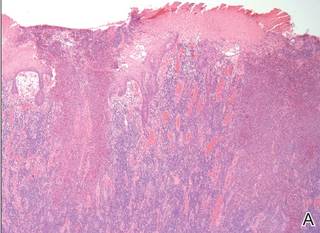

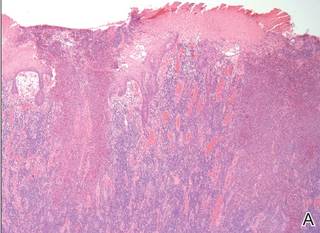

Basic hematologic and metabolic laboratory test results as well as blood cultures were negative. Wound culture was positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Histologic examination showed interface dermatitis with subepidermal vesicle (Figure 2). Scattered necrotic keratinocytes were present in the adjacent epidermis, and focal subtle vacuolar alteration of the dermoepidermal junction was seen (Figure 3). Sparse perivascular mononuclear cells and scattered melanophages were present in the dermis. Direct immunofluorescence showed no diagnostic immunopathologic abnormality. Focal weak nonspecific vascular positivity for IgG and C3 was seen, but IgA and IgM were negative. Although not specific, these changes were compatible with EAI in the clinical context provided. The diagnosis of bullous EAI with superimposed staphylococcal infection was made.

Although rare, there have been reports of a bullous variant of EAI. Flanagan et al4 described 3 cases of bullous EAI with histopathology similar to our case. All 3 biopsies showed subepidermal separation with a mild perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was negative in 2 cases but showed nonspecific weak patchy deposition of IgM along the dermoepidermal junction.4 Although our case was negative for IgM, there was a similar weak nonspecific distribution of IgG. Kokturk et al5 described a case of bullous EAI in a man with repeated exposure to a space heater. The lesions showed subepidermal separation of the epidermis; increased elastic fibers; dilated dermal capillaries; melanophages in the upper dermis; and a mild, superficial, perivascular-lymphocytic infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence showed no immune deposits.5 Several earlier cases of bullae associated with EAI have been reported in the literature but were thought to be bullous lichen planus superimposed on EAI.6 Our case, which exhibited similar historical, physical, and histopathologic findings, strengthens the argument for a defined bullous variant of EAI.

- Baruchin AM. Erythema ab igne—a neglected entity? Burns. 1994;20:460-462.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer−induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature [published online October 4, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230.

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162:77-78.

- Flanagan N, Watson R, Sweeney E, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:1159-1160.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Horio T, Imamura S. Bullous lichen planus developed on erythema ab igne. J Dermatol. 1986;13:203-207.

To the Editor:

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a reticular erythematous hyperpigmentation of skin repeatedly exposed to moderate heat.1 It usually is asymptomatic, though some patients report itching or burning at the site.2 Historically caused by exposure to coal stoves or open fires, EAI has become increasingly common among individuals using space heaters, heating pads, or laptop computers near bare skin.2,3 Although EAI itself is benign and usually resolves with the removal of the exposure, it remains of clinical importance because of its association with underlying chronic disease, as chronic pain often is managed with frequent heating pad or hot water bottle use.2 Additionally, accurate diagnosis is important given the future risk for malignancy, as chronic changes of EAI have been reported to lead to squamous cell carcinoma or rarely Merkel cell carcinoma.2 Erythema ab igne is not traditionally associated with the formation of bullae; however, we present a case of bullous EAI that we believe highlights the importance of including this condition in the differential diagnosis of bullous disorders.

A 55-year-old man was admitted for presumed cellulitis of the bilateral legs. The patient had developed hyperpigmented discoloration of the medial surface of both legs with subsequent formation of tense bullae over the last 2 months. The dermatology department was consulted, as there was concern for bullous pemphigoid. The patient’s medical history was notable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diet-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis C virus with cirrhosis. The patient denied pruritus, pain, or known exposure of the legs to potential irritants prior to developing the lesions; however, with additional questioning he did report frequently sitting in front of a space heater with bare legs. Physical examination revealed multiple areas of reticulated erythematous hyperpigmentation with several overlying bullae (Figure 1). Many of the bullae were unroofed with full-thickness ulceration. Biopsies were taken for hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2) and direct immunofluorescence.

Basic hematologic and metabolic laboratory test results as well as blood cultures were negative. Wound culture was positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Histologic examination showed interface dermatitis with subepidermal vesicle (Figure 2). Scattered necrotic keratinocytes were present in the adjacent epidermis, and focal subtle vacuolar alteration of the dermoepidermal junction was seen (Figure 3). Sparse perivascular mononuclear cells and scattered melanophages were present in the dermis. Direct immunofluorescence showed no diagnostic immunopathologic abnormality. Focal weak nonspecific vascular positivity for IgG and C3 was seen, but IgA and IgM were negative. Although not specific, these changes were compatible with EAI in the clinical context provided. The diagnosis of bullous EAI with superimposed staphylococcal infection was made.

Although rare, there have been reports of a bullous variant of EAI. Flanagan et al4 described 3 cases of bullous EAI with histopathology similar to our case. All 3 biopsies showed subepidermal separation with a mild perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was negative in 2 cases but showed nonspecific weak patchy deposition of IgM along the dermoepidermal junction.4 Although our case was negative for IgM, there was a similar weak nonspecific distribution of IgG. Kokturk et al5 described a case of bullous EAI in a man with repeated exposure to a space heater. The lesions showed subepidermal separation of the epidermis; increased elastic fibers; dilated dermal capillaries; melanophages in the upper dermis; and a mild, superficial, perivascular-lymphocytic infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence showed no immune deposits.5 Several earlier cases of bullae associated with EAI have been reported in the literature but were thought to be bullous lichen planus superimposed on EAI.6 Our case, which exhibited similar historical, physical, and histopathologic findings, strengthens the argument for a defined bullous variant of EAI.

To the Editor:

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a reticular erythematous hyperpigmentation of skin repeatedly exposed to moderate heat.1 It usually is asymptomatic, though some patients report itching or burning at the site.2 Historically caused by exposure to coal stoves or open fires, EAI has become increasingly common among individuals using space heaters, heating pads, or laptop computers near bare skin.2,3 Although EAI itself is benign and usually resolves with the removal of the exposure, it remains of clinical importance because of its association with underlying chronic disease, as chronic pain often is managed with frequent heating pad or hot water bottle use.2 Additionally, accurate diagnosis is important given the future risk for malignancy, as chronic changes of EAI have been reported to lead to squamous cell carcinoma or rarely Merkel cell carcinoma.2 Erythema ab igne is not traditionally associated with the formation of bullae; however, we present a case of bullous EAI that we believe highlights the importance of including this condition in the differential diagnosis of bullous disorders.

A 55-year-old man was admitted for presumed cellulitis of the bilateral legs. The patient had developed hyperpigmented discoloration of the medial surface of both legs with subsequent formation of tense bullae over the last 2 months. The dermatology department was consulted, as there was concern for bullous pemphigoid. The patient’s medical history was notable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diet-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis C virus with cirrhosis. The patient denied pruritus, pain, or known exposure of the legs to potential irritants prior to developing the lesions; however, with additional questioning he did report frequently sitting in front of a space heater with bare legs. Physical examination revealed multiple areas of reticulated erythematous hyperpigmentation with several overlying bullae (Figure 1). Many of the bullae were unroofed with full-thickness ulceration. Biopsies were taken for hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2) and direct immunofluorescence.

Basic hematologic and metabolic laboratory test results as well as blood cultures were negative. Wound culture was positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Histologic examination showed interface dermatitis with subepidermal vesicle (Figure 2). Scattered necrotic keratinocytes were present in the adjacent epidermis, and focal subtle vacuolar alteration of the dermoepidermal junction was seen (Figure 3). Sparse perivascular mononuclear cells and scattered melanophages were present in the dermis. Direct immunofluorescence showed no diagnostic immunopathologic abnormality. Focal weak nonspecific vascular positivity for IgG and C3 was seen, but IgA and IgM were negative. Although not specific, these changes were compatible with EAI in the clinical context provided. The diagnosis of bullous EAI with superimposed staphylococcal infection was made.

Although rare, there have been reports of a bullous variant of EAI. Flanagan et al4 described 3 cases of bullous EAI with histopathology similar to our case. All 3 biopsies showed subepidermal separation with a mild perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was negative in 2 cases but showed nonspecific weak patchy deposition of IgM along the dermoepidermal junction.4 Although our case was negative for IgM, there was a similar weak nonspecific distribution of IgG. Kokturk et al5 described a case of bullous EAI in a man with repeated exposure to a space heater. The lesions showed subepidermal separation of the epidermis; increased elastic fibers; dilated dermal capillaries; melanophages in the upper dermis; and a mild, superficial, perivascular-lymphocytic infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence showed no immune deposits.5 Several earlier cases of bullae associated with EAI have been reported in the literature but were thought to be bullous lichen planus superimposed on EAI.6 Our case, which exhibited similar historical, physical, and histopathologic findings, strengthens the argument for a defined bullous variant of EAI.

- Baruchin AM. Erythema ab igne—a neglected entity? Burns. 1994;20:460-462.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer−induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature [published online October 4, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230.

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162:77-78.

- Flanagan N, Watson R, Sweeney E, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:1159-1160.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Horio T, Imamura S. Bullous lichen planus developed on erythema ab igne. J Dermatol. 1986;13:203-207.

- Baruchin AM. Erythema ab igne—a neglected entity? Burns. 1994;20:460-462.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer−induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature [published online October 4, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230.

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162:77-78.

- Flanagan N, Watson R, Sweeney E, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:1159-1160.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Horio T, Imamura S. Bullous lichen planus developed on erythema ab igne. J Dermatol. 1986;13:203-207.

Practice Points

- Consider erythema ab igne (EAI) as a potential differential diagnosis in bullous eruptions.

- Space heaters, heating pads, and even laptop computers should be considered as potential causes of EAI.

Vegetative Sacral Plaque in a Patient With Human Immunodeficiency Virus

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Vegetans

Histopathologic examination using hematoxylin and eosin stain demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with granulation tissue, ulceration, and abundant exudate joined by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate that included a myriad of eosinophils (Figure, A). At higher power (Figure, B), many single and multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes showed ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin within zones of ulceration and crust. Viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody assay identified herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with herpes simplex vegetans. He was initially treated with oral acyclovir and then oral famciclovir but showed minimal improvement. Eventually, he was referred to surgery and the mass was totally excised with clear margins and no evidence of underlying malignancy.

|

| Histopathology revealed marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Many multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes with ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin were shown (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, with a notably increased incidence and prevalence among individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1 Although typical HSV manifestation in immunocompetent patients includes clustered vesicles and/or ulcerations, immunocompromised patients may have unusual presentations, such as persistent and extensive ulcerations or nodular hyperkeratotic lesions.2,3 Herpes vegetans, a term used to describe these atypical exophytic lesions, rarely has been reported in literature, but its presence should raise suspicion for possible underlying immunocompromise. The pathogenesis behind the hypertrophic nature of these lesions is not well understood, but it is postulated that the immune dysregulation from concomitant HIV and HSV infection plays a role.2 Overproduction of tumor necrosis factor and IL-6 by HIV-infected dermal dendritic cells causes an increase in antiapoptotic factors within the epidermis, resulting in enhanced keratinocyte proliferation and clinical hyperkeratosis.2,4

The differential diagnosis for herpes vegetans is somewhat broad, owing to the verrucous and often eroded appearance of the lesions. Biopsy and cultures can be obtained to differentiate from condyloma acuminatum, condyloma latum (secondary syphilis), pyoderma vegetans, pemphigus vegetans, granuloma inguinale, extraintestinal Crohn disease, deep fungal infections, cutaneous tuberculosis, and malignancy.2-4 Histopathology shows epithelial hyperplasia and ulceration with scattered multinucleate keratinocytes, usually at the periphery of the ulcer, and intranuclear inclusions typical of HSV. In addition, a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils is usually present beneath the base of the ulcer.2,4

Treatment options for herpes vegetans are limited due to the high prevalence of acyclovir-resistant (ACV-R) HSV-2 strains in HIV patients. Valacyclovir and penciclovir have been largely ineffective against ACV-R HSV due to their dependence on the same enzyme—thymidine kinase—involved in the mechanism of acyclovir resistance. Intravenous foscarnet and cidofovir have shown efficacy against ACV-R virus, but concerns of nephrotoxicity have limited their use over prolonged intervals.5 Castelo-Soccio et al6 reported promising results with intralesional cidofovir. This route of administration provides the advantage of increased bioavailability with reduced risk for nephrotoxicity.6 Finally, surgical resection may be considered for refractory lesions to circumvent the toxicity from systemically administered drugs.3

- Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

- Patel AB, Rosen T. Herpes vegetans as a sign of HIV infection. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Chung VQ, Parker DC, Parker SR. Surgical excision for vegetative herpes simplex virus infection. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1374-1379.

- Beasley KL, Cooley GE, Kao GF, et al. Herpes simplex vegetans: atypical genital herpes infection in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):860-863.

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320.

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Vegetans

Histopathologic examination using hematoxylin and eosin stain demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with granulation tissue, ulceration, and abundant exudate joined by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate that included a myriad of eosinophils (Figure, A). At higher power (Figure, B), many single and multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes showed ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin within zones of ulceration and crust. Viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody assay identified herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with herpes simplex vegetans. He was initially treated with oral acyclovir and then oral famciclovir but showed minimal improvement. Eventually, he was referred to surgery and the mass was totally excised with clear margins and no evidence of underlying malignancy.

|

| Histopathology revealed marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Many multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes with ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin were shown (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, with a notably increased incidence and prevalence among individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1 Although typical HSV manifestation in immunocompetent patients includes clustered vesicles and/or ulcerations, immunocompromised patients may have unusual presentations, such as persistent and extensive ulcerations or nodular hyperkeratotic lesions.2,3 Herpes vegetans, a term used to describe these atypical exophytic lesions, rarely has been reported in literature, but its presence should raise suspicion for possible underlying immunocompromise. The pathogenesis behind the hypertrophic nature of these lesions is not well understood, but it is postulated that the immune dysregulation from concomitant HIV and HSV infection plays a role.2 Overproduction of tumor necrosis factor and IL-6 by HIV-infected dermal dendritic cells causes an increase in antiapoptotic factors within the epidermis, resulting in enhanced keratinocyte proliferation and clinical hyperkeratosis.2,4

The differential diagnosis for herpes vegetans is somewhat broad, owing to the verrucous and often eroded appearance of the lesions. Biopsy and cultures can be obtained to differentiate from condyloma acuminatum, condyloma latum (secondary syphilis), pyoderma vegetans, pemphigus vegetans, granuloma inguinale, extraintestinal Crohn disease, deep fungal infections, cutaneous tuberculosis, and malignancy.2-4 Histopathology shows epithelial hyperplasia and ulceration with scattered multinucleate keratinocytes, usually at the periphery of the ulcer, and intranuclear inclusions typical of HSV. In addition, a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils is usually present beneath the base of the ulcer.2,4

Treatment options for herpes vegetans are limited due to the high prevalence of acyclovir-resistant (ACV-R) HSV-2 strains in HIV patients. Valacyclovir and penciclovir have been largely ineffective against ACV-R HSV due to their dependence on the same enzyme—thymidine kinase—involved in the mechanism of acyclovir resistance. Intravenous foscarnet and cidofovir have shown efficacy against ACV-R virus, but concerns of nephrotoxicity have limited their use over prolonged intervals.5 Castelo-Soccio et al6 reported promising results with intralesional cidofovir. This route of administration provides the advantage of increased bioavailability with reduced risk for nephrotoxicity.6 Finally, surgical resection may be considered for refractory lesions to circumvent the toxicity from systemically administered drugs.3

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Vegetans

Histopathologic examination using hematoxylin and eosin stain demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with granulation tissue, ulceration, and abundant exudate joined by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate that included a myriad of eosinophils (Figure, A). At higher power (Figure, B), many single and multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes showed ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin within zones of ulceration and crust. Viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody assay identified herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with herpes simplex vegetans. He was initially treated with oral acyclovir and then oral famciclovir but showed minimal improvement. Eventually, he was referred to surgery and the mass was totally excised with clear margins and no evidence of underlying malignancy.

|

| Histopathology revealed marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Many multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes with ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin were shown (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, with a notably increased incidence and prevalence among individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1 Although typical HSV manifestation in immunocompetent patients includes clustered vesicles and/or ulcerations, immunocompromised patients may have unusual presentations, such as persistent and extensive ulcerations or nodular hyperkeratotic lesions.2,3 Herpes vegetans, a term used to describe these atypical exophytic lesions, rarely has been reported in literature, but its presence should raise suspicion for possible underlying immunocompromise. The pathogenesis behind the hypertrophic nature of these lesions is not well understood, but it is postulated that the immune dysregulation from concomitant HIV and HSV infection plays a role.2 Overproduction of tumor necrosis factor and IL-6 by HIV-infected dermal dendritic cells causes an increase in antiapoptotic factors within the epidermis, resulting in enhanced keratinocyte proliferation and clinical hyperkeratosis.2,4

The differential diagnosis for herpes vegetans is somewhat broad, owing to the verrucous and often eroded appearance of the lesions. Biopsy and cultures can be obtained to differentiate from condyloma acuminatum, condyloma latum (secondary syphilis), pyoderma vegetans, pemphigus vegetans, granuloma inguinale, extraintestinal Crohn disease, deep fungal infections, cutaneous tuberculosis, and malignancy.2-4 Histopathology shows epithelial hyperplasia and ulceration with scattered multinucleate keratinocytes, usually at the periphery of the ulcer, and intranuclear inclusions typical of HSV. In addition, a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils is usually present beneath the base of the ulcer.2,4

Treatment options for herpes vegetans are limited due to the high prevalence of acyclovir-resistant (ACV-R) HSV-2 strains in HIV patients. Valacyclovir and penciclovir have been largely ineffective against ACV-R HSV due to their dependence on the same enzyme—thymidine kinase—involved in the mechanism of acyclovir resistance. Intravenous foscarnet and cidofovir have shown efficacy against ACV-R virus, but concerns of nephrotoxicity have limited their use over prolonged intervals.5 Castelo-Soccio et al6 reported promising results with intralesional cidofovir. This route of administration provides the advantage of increased bioavailability with reduced risk for nephrotoxicity.6 Finally, surgical resection may be considered for refractory lesions to circumvent the toxicity from systemically administered drugs.3

- Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

- Patel AB, Rosen T. Herpes vegetans as a sign of HIV infection. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Chung VQ, Parker DC, Parker SR. Surgical excision for vegetative herpes simplex virus infection. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1374-1379.

- Beasley KL, Cooley GE, Kao GF, et al. Herpes simplex vegetans: atypical genital herpes infection in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):860-863.

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320.

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126.

- Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

- Patel AB, Rosen T. Herpes vegetans as a sign of HIV infection. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Chung VQ, Parker DC, Parker SR. Surgical excision for vegetative herpes simplex virus infection. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1374-1379.

- Beasley KL, Cooley GE, Kao GF, et al. Herpes simplex vegetans: atypical genital herpes infection in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):860-863.

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320.

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126.

A 53-year-old man presented to our clinic with a sacral mass that had progressively enlarged over 2 years. The patient reported occasional oozing from the mass as well as pain when laying flat but denied fever or other symptoms. His medical history was remarkable for human immunodeficiency virus infection with variable adherence to a highly active antiretroviral therapy regimen. At the time of presentation, the patient had a CD4 lymphocyte count of 78 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500–1400 cells/mm3) and a viral load of 290 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL). Physical examination revealed a 10-cm discrete, moist and pink, exophytic plaque on the sacrum with superficial erosions. The plaque was nontender and without associated lymphadenopathy. The skin and mucous membranes were otherwise clear. A cutaneous biopsy specimen was obtained from the tumor and sent for histopathologic analysis.