User login

Shoulder dystocia: Taking the fear out of management

Webcast: Factors that contribute to overall contraceptive efficacy and risks

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Access Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception:

- Obesity and contraceptive efficacy and risks

- How to use the CDC's online tools to manage complex cases in contraception

Helpful resource for your practice:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Access Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception:

- Obesity and contraceptive efficacy and risks

- How to use the CDC's online tools to manage complex cases in contraception

Helpful resource for your practice:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Access Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception:

- Obesity and contraceptive efficacy and risks

- How to use the CDC's online tools to manage complex cases in contraception

Helpful resource for your practice:

Webcast: Obesity and contraceptive efficacy and risks

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channelAccess Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception: Helpful resources for your practice: |

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channelAccess Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception: Helpful resources for your practice: |

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channelAccess Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception: Helpful resources for your practice: |

Webcast: How to use the CDC's online tools to manage complex cases in contraception

| Access the online tools referenced in this Webcast: |

| Access the online tools referenced in this Webcast: |

| Access the online tools referenced in this Webcast: |

Your teenage patient and contraception: Think “long-acting” first

CASE: Teen patient asks to switch contraceptive methods

A 17-year-old nulliparous woman comes to your clinic for an annual examination. She has no significant health problems, and her examination is normal. She notes that she was started on oral contraceptives (OCs) the year before because of heavy menstrual flow and a desire for birth control but has trouble remembering to take them—though she does usually use condoms. She asks your advice about switching to a different method but indicates that she has lost her health insurance coverage.

What can you offer her as an effective, low-cost contraceptive?

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods are especially suited for adolescent and young adult women, for whom daily compliance with a shorter-acting contraceptive may be problematic. Five LARC methods are available in the United States, including a new levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Liletta), which received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) this year. Like Mirena, Liletta contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel that is released over time. Liletta was introduced by the nonprofit organization Medicines360 and its commercial partner Actavis Pharma in response to evidence that poor women continue to lack access to LARC because of cost or problems with insurance coverage.1

For providers who practice in settings eligible for 340B pricing, Liletta costs $50, a fraction of the cost of alternative intrauterine devices (IUDs). The cost is slightly higher for non-340B providers but is still significantly lower than the cost of other IUDs. For health care practices, the reduced price of Liletta may make it feasible for them to offer LARC to more patients. The reduced pricing also makes Liletta an attractive option for women who choose to pay for the device directly rather than use insurance, such as the patient described above.

Patient experience with Liletta also is key. Not surprisingly, Liletta’s clinical trial found patient satisfaction to be similar to that of Mirena users.2 The failure rate is less than 1%, again comparable to Mirena. The rate of pelvic infection with Liletta use was 0.5%, also comparable to previously published data.3

One difference between Liletta and Mirena is that Liletta carries FDA approval for 3 years of contraceptive efficacy, compared with 5 years for Mirena. In order to make Liletta available to US patients now, Medicines360 decided to apply for 3-year contraceptive labeling while 5- and 7-year efficacy data are being collected. Like Mirena, Liletta is expected to provide excellent contraception for at least 5 years.

How to insert Liletta

- While still pinching the insertion tube, slide the tube through the cervical canal until the upper edge of the flange is approximately 1.5 to 2 cm from the cervix. Do not force the inserter. If necessary, dilate the cervical canal. Release your hold on the tenaculum.

- Hold the insertion tube with the fingers of one hand (Hand A) and the rod with the fingers of the other hand (Hand B).

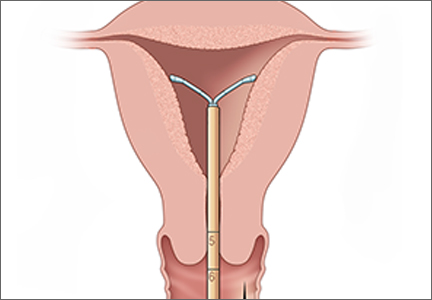

- Holding the rod in place (Hand B), relax your pinch on the tube and pull the insertion tube back with Hand A to the edge of the second indent of the rod. This will allow the IUS arms to unfold in the lower uterine segment (FIGURE). Wait 10 to 15 seconds for the arms of the IUS to open fully.

- Apply gentle traction with the tenaculum before advancing the IUS. With Hand A still holding the proximal end of the tube, advance both the insertion tube and rod simultaneously up to the uterine fundus. You will feel slight resistance when the IUS is at the fundus. Make sure the flange is touching the cervix when the IUS reaches the uterine fundus. Fundal positioning is important to prevent expulsion.

- Hold the rod still (Hand B) while pulling the insertion tube back with Hand A to the ring of the rod. While holding the inserter tube with Hand A, withdraw the rod from the insertion tube all of the way out to prevent the rod from catching on the knot at the lower end of the IUS. Completely remove the insertion tube.

- Using blunt-tipped sharp scissors, cut the IUS threads perpendicular to the thread length, leaving about 3 cm outside of the cervix. Do not apply tension or pull on the threads when cutting to prevent displacing the IUS. Insertion is now complete.

Source: Liletta [package insert]. Actavis Pharma, Parsippany, NJ; 2015.

Skyla is another LARC option for womenseeking an LNG-IUS for contraception. It provides highly effective contraception for at least 3 years through the release of 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel over time. Skyla’s reduced levonorgestrel content, as compared with Mirena and Liletta, means that fewer users will experience amenorrhea (13% vs 25%).

Paragard is a nonhormonal IUD that uses copper for contraceptive efficacy. The device contains a total of 380 mm of copper. Possible mechanisms of action include interference with sperm migration in the uterus and damage to or destruction of ova. It is FDA-approved for at least 10 years of use. The lack of any hormone in Paragard IUDs may make them attractive to women who do not wish to experience amenorrhea.

Nexplanon is a subdermal implant containing 68 mg of etonogestrel; it is approved for at least 3 years of use. It is the only LARC method that does not require a pelvic examination. Providers are required to complete a training course offered by the manufacturer to ensure proper placement and removal technique.

LARC should be a first-line birth control option

The primary indication for LARC is preg-nancy prevention. Because LARC methods are the most effective reversible means to prevent pregnancy—apart from complete abstinence from sexual intercourse—they should be offered as first-line birth control options to patients who do not wish to conceive. The ability to discontinue LARC methods is an attractive option for women who may want to become pregnant in the future, such as the patient in the opening vignette.

Efficacy rates are high

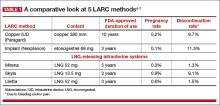

Because LARC methods do not require users to take action daily or prior to intercourse, they carry a risk of pregnancy of less than 1% (TABLE 1)4-7—equal to or better than rates seen with tubal sterilization. In comparison, the OC pill has a typical use contraceptive failure rate of about 8%.

LARC still has a low utilization rate

It is unfortunate that barriers to LARC methods remain in the United States (see, for example, “National organization identifies barriers to LARC,” above). As recently as 2011 to 2013, only 7.2% of US women aged 15 to 44 years used a LARC method.8 Provider inexperience and patient fears surrounding LARC use remain major barriers. In the past, nulliparity and young age were thought to be contraindications to IUD use. Research and experience have demonstrated, however, that IUDs and contraceptive implants are safe for use in young women and those who have not had children.

Cost barriers also have significantly limited the use of LARC methods. Over time, however, these contraceptives have become less costly to patients, and most insurance providers routinely cover LARC devices and insertion fees. The contraceptive mandate of the Affordable Care Act ensures coverage of contraception, including LARC, for interested women. These trends suggest continued improvement in women’s access to LARC.

National organization identifies barriers to LARC

In 2014, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), with support from Bayer Healthcare, organized a meeting of key opinion leaders to discuss ways to eliminate barriers to the most effective contraceptive methods, better known as long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). The resultant issue brief, Women’s Health: Approaches to improving unintended pregnancy rates in the United States, identified a number of key barriers:

- Financial and logistical obstacles. The consensus attendees agreed that LARC methods should be offered to all women not planning a pregnancy in the next 2 years, but acknowledged that operational or administrative process issues sometimes interfere with this goal. One of the most prominent of these issues was the lack of opportunity for same-day insertion of LARC. Other issues included the cost to stock LARC methods, a lack of understanding of billing and reimbursement for LARC, reimbursement policies that prohibit billing for the visit and placement on the same day, and an overabundance of paperwork.

- Timing of the contraceptive counseling session. Many women fail to return for the 6-week postpartum visit—the visit typically set aside for counseling about contraception.

- Lack of a quality measure that would “motivate change in clinical practice.”1 One option: Treat family planning as a “vital sign” that needs to be addressed during the annual visit. “This would lead to stronger evidence for effecting change,” the report notes.1

- Lack of adequate communication skills by the provider. According to the NCQA report, “There are strong positive relationships between a health care team member’s communication skills and a patient’s willingness to follow through with medical recommendations.”1 The establishment of a “current counseling approach” that emphasizes the efficiency and effectiveness of LARC methods as well as the tremendous impact an unintended pregnancy would have on a woman’s whole life course would help improve provider-patient communication and increase the likelihood of LARC methods being utilized.1

- Lack of receptivity among some patients. For some women, the person delivering the message is as important as the message itself, depending on social and cultural norms. Sensitivity of health care providers to these nuances of communication can help enhance patient receptivity to the key message. As the NCQA report notes, “Physicians and the health care system are not always the most trusted source of information, and understanding disparities in contraception care will be important in changing patient behavior.”1

- Basic issues such as cost and access to care.1 Not all women are covered by insurance, particularly in states that opted against expanding access to Medicaid. For these women, the cost of LARC methods and insertion may be prohibitive.

Reference

Noncontraceptive benefits include reduced bleeding

The 3 LNG-IUS methods and the subdermal implant offer several benefits beyond contraception. Because of their progestin content, these methods reduce or even eliminate menses. This benefit can be very helpful for women who experience heavy menstrual periods and the consequent risk of anemia. Because of reduced menstrual flow, users of hormonal LARC methods also commonly experience less cramping associated with menses.

Women with endometriosis often benefit from hormonal LARC methods, as the disease is suppressed by the progestin component. Users of IUDs also have a reduced risk of endometrial cancer.

Contraindications to LARC

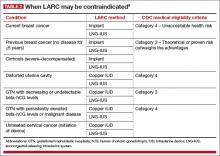

There are few contraindications to LARC methods, making them an appropriate choice for most women. The US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), contain guidelines that are based on the best available evidence.9 Contraceptive methods that are labeled as Category 1 or 2 are not contraindicated for most women. Methods that fall into Category 3 (theoretical or proven risks outweigh the advantages) or Category 4 (unacceptable health risk) are contraindicated (TABLE 2).9

IUDs once were thought to expose women to an increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, but this fear has long been disproven. Screening for chlamydia can be performed at the time of placement, as recommended annually for women younger than 25 years. Unless there is concern for active cervical or uterine infection, there is no need to delay insertion of an IUD while awaiting test results. In most cases, women found to have positive cultures after insertion can be treated successfully without IUD removal.

Main adverse effect is altered bleeding patterns

Adverse effects vary depending on the method being used. All LARC methods may affect menstrual patterns. For example, clinical trials involving the copper IUD indicate that abnormal heavy bleeding may lead to discontinuation in up to 10% of users.5,10 Amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea is uncommon with this method and rarely leads to discontinuation. For example, in one trial involving more than 900 women using a copper IUD for up to 5 years, there were no discontinuations due to amenorrhea. Dysmenorrhea may arise, but data from clinical trials indicate that its frequency decreases over time. In one trial, the frequency of any menstrual pain decreased from about 9% of users to 5% after 8 months or more of use.

The LNG-IUS also can be associated with abnormal uterine bleeding. In contrast to the copper IUD, LNG devices tend to reduce menstrual bleeding and can be unpredictable. Clinical trials involving the 5-year 52-mg LNG-IUS indicate that bleeding decreases over time, with as many as 70% of users developing amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea.5,11 However, some women using an LNG-IUS experience heavy bleeding— although the frequency of such bleeding tends to be substantially less than that experienced by copper IUD users.7

A lack of comparative trials makes it unclear whether the newer 3-year LNG-IUS devices are associated with a significantly altered bleeding pattern. Noncomparative data from the package insert for Skyla suggest that women using it may have a higher frequency of heavy menstrual bleeding and less amenorrhea than users of the 5-year device.6

Data from a 3-year clinical trial of the newest 52-mg LNG-IUS (Liletta) indicate that bleeding and dysmenorrhea led to discontinuation 1% to 2% of the time.2

Although the concentration of progestincirculating systemically is low with the various LNG-IUS devices, some women may experience symptoms such as mood swings, headaches, acne, and breast tenderness.

Expulsions during the first year of use of the copper IUD and the 3 LNG-IUS devices range from 2% to 10%, with the higher rates associated with immediate postpartum insertion.5

Uterine perforation has been reported in about 1 of every 1,000 insertions. Other adverse events are uncommon.

Clinical trials indicate that about 11% of implant users will discontinue the method due to bleeding abnormalities.12 About 25% to 30% of users will experience heavy or prolonged bleeding, while up to 33% will experience infrequent bleeding or amenorrhea. About 50% of implant users will experience improved bleeding patterns over time.

Other reasons for discontinuation of implant use in a very small percentage of users include emotional lability, weight gain, acne, and headaches.4 Complications due to insertion and removal are rare and include pain, bleeding, and hematoma formation.

Public health impact of LARC methods

An important question in regard to LARC use is: How do we best provide safe and effective contraception for teens and young adult women? There is increasing evidence that, with appropriate counseling and the removal of cost barriers, LARC methods can have a significant public health impact in this population.

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project, a cohort study in a teenage population of women in the St. Louis, Missouri, area, achieved increased utilization of LARC methods and significantly lower rates of pregnancy, birth, and abortion.13 Investigators proactively counseled young women about the advantages of LARC methods and offered them free of charge. As a result, 72% of women in the study chose an IUD or implant as their method of contraception. Pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates among participants were 34.0, 19.4, and 9.7 per 1,000 teens, respectively. By comparison, national statistics during the same time frame for pregnancy, birth, and abortion were 158.5, 94.0, and 41.5 per 1,000 US teens, respectively.13

A similar project in Colorado received $23.6 million in 2009 from an outside donor to make LARC methods more affordable to patients in family planning clinics in the state.14 Between 2009 and 2014, 30,000 contraceptive implants or IUDs were made available at low or no cost to low-income women attending 68 family planning clinics statewide. The use of these methods at participating clinics quadrupled. Further, the teen birth rate declined by 40% between 2009 and 2013—from 37 to 22 births per 1,000 teens.14 Seventy-five percent of this decline was attributable to increased use of these methods. The teen abortion rate declined by 35% in the same time frame.

In 2014, the Colorado governor’s office indicated that the state had saved $42.5 million in health care expenditures associated with teen births. It was estimated that, for every dollar spent on contraceptives, the state saved $5.68 in Medicaid costs. However, a bipartisan bill to continue funding the project has failed so far in 2015 due to concerns among some legislators that these methods—particularly the IUDs—are abortifacients. The reduced cost of the 3-year LNG-IUS (Liletta) and recent guidance from the US Department of Health and Human Services mandating that at least 1 form of contraception in each of the FDA-approved categories must be covered by insurers may help to overcome this barrier.

CASE: Resolved

You counsel the patient about the value of each LARC method, letting her know that they are all highly effective in the prevention of pregnancy. You also let her know how each method would affect her menstrual cycle and acknowledge that she may have a preference for whether the contraceptive is placed in her uterus or under the skin of her arm. She chooses the contraceptive implant, which you insert during the same visit. At a follow-up visit 6 weeks later, she reports satisfaction with the method.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Dehlendorf C, Rodriguez MI, Levy K, Borrero S, Steinauer J.Disparities in family planning. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):214–220.

2. Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92(1):10–16.

3. Sufrin C, Postlethwaite D, Armstrong MA, et al. Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis screening at intrauterine device insertion and pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1314–1321.

4. Espey E, Ogburn T. Long-acting reversible contraceptives—intrauterine devices and the contraceptive implant. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):705–719.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):184–196.

6. Skyla [package insert]. Bayer Healthcare, Wayne, NJ; 2013.

7. Liletta [package insert]. Actavis Pharma, Parsippany, NJ; 2015.

8. Branum AM, Jones J. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: NCHS Data Brief No. 188: Trends in Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Use Among US Women Aged 15–44. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db188.htm. Published February 2015. Accessed August 14, 2015.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR4):1–86.

10. Andersson K, Odlind VL, Rybo G. Levonorgestrel-releasing and copper-releasing (Nova T) IUDs during five years of use; a randomized comparative trial. Contraception. 1994;49(1):56–72.

11. Sivin I, Stern J, Diaz J, et al. Two years of intrauterine contraception with levonorgestrel and copper: a randomized comparison of the TCu 380Ag and levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day devices. Contraception. 1987;35(3):245–255.

12. Mansour F, Korver T, Marintcheva-Petrova M, Fraser IS. The effects of Implanon on menstrual bleeding patterns. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13(suppl 1):13–28.

13. Secura GM, Madden T, McNicholas C, et al. Provision of no-cost, long-acting contraception and teenage pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1316–1323.

14. Tavernise S. Colorado’s effort against teenage pregnancies is a startling success. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/06/science/colorados-push-against-teenage-pregnancies-is-a-startling-success.html. Published July 6, 2015. Accessed August 17, 2015.

CASE: Teen patient asks to switch contraceptive methods

A 17-year-old nulliparous woman comes to your clinic for an annual examination. She has no significant health problems, and her examination is normal. She notes that she was started on oral contraceptives (OCs) the year before because of heavy menstrual flow and a desire for birth control but has trouble remembering to take them—though she does usually use condoms. She asks your advice about switching to a different method but indicates that she has lost her health insurance coverage.

What can you offer her as an effective, low-cost contraceptive?

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods are especially suited for adolescent and young adult women, for whom daily compliance with a shorter-acting contraceptive may be problematic. Five LARC methods are available in the United States, including a new levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Liletta), which received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) this year. Like Mirena, Liletta contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel that is released over time. Liletta was introduced by the nonprofit organization Medicines360 and its commercial partner Actavis Pharma in response to evidence that poor women continue to lack access to LARC because of cost or problems with insurance coverage.1

For providers who practice in settings eligible for 340B pricing, Liletta costs $50, a fraction of the cost of alternative intrauterine devices (IUDs). The cost is slightly higher for non-340B providers but is still significantly lower than the cost of other IUDs. For health care practices, the reduced price of Liletta may make it feasible for them to offer LARC to more patients. The reduced pricing also makes Liletta an attractive option for women who choose to pay for the device directly rather than use insurance, such as the patient described above.

Patient experience with Liletta also is key. Not surprisingly, Liletta’s clinical trial found patient satisfaction to be similar to that of Mirena users.2 The failure rate is less than 1%, again comparable to Mirena. The rate of pelvic infection with Liletta use was 0.5%, also comparable to previously published data.3

One difference between Liletta and Mirena is that Liletta carries FDA approval for 3 years of contraceptive efficacy, compared with 5 years for Mirena. In order to make Liletta available to US patients now, Medicines360 decided to apply for 3-year contraceptive labeling while 5- and 7-year efficacy data are being collected. Like Mirena, Liletta is expected to provide excellent contraception for at least 5 years.

How to insert Liletta

- While still pinching the insertion tube, slide the tube through the cervical canal until the upper edge of the flange is approximately 1.5 to 2 cm from the cervix. Do not force the inserter. If necessary, dilate the cervical canal. Release your hold on the tenaculum.

- Hold the insertion tube with the fingers of one hand (Hand A) and the rod with the fingers of the other hand (Hand B).

- Holding the rod in place (Hand B), relax your pinch on the tube and pull the insertion tube back with Hand A to the edge of the second indent of the rod. This will allow the IUS arms to unfold in the lower uterine segment (FIGURE). Wait 10 to 15 seconds for the arms of the IUS to open fully.

- Apply gentle traction with the tenaculum before advancing the IUS. With Hand A still holding the proximal end of the tube, advance both the insertion tube and rod simultaneously up to the uterine fundus. You will feel slight resistance when the IUS is at the fundus. Make sure the flange is touching the cervix when the IUS reaches the uterine fundus. Fundal positioning is important to prevent expulsion.

- Hold the rod still (Hand B) while pulling the insertion tube back with Hand A to the ring of the rod. While holding the inserter tube with Hand A, withdraw the rod from the insertion tube all of the way out to prevent the rod from catching on the knot at the lower end of the IUS. Completely remove the insertion tube.

- Using blunt-tipped sharp scissors, cut the IUS threads perpendicular to the thread length, leaving about 3 cm outside of the cervix. Do not apply tension or pull on the threads when cutting to prevent displacing the IUS. Insertion is now complete.

Source: Liletta [package insert]. Actavis Pharma, Parsippany, NJ; 2015.

Skyla is another LARC option for womenseeking an LNG-IUS for contraception. It provides highly effective contraception for at least 3 years through the release of 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel over time. Skyla’s reduced levonorgestrel content, as compared with Mirena and Liletta, means that fewer users will experience amenorrhea (13% vs 25%).

Paragard is a nonhormonal IUD that uses copper for contraceptive efficacy. The device contains a total of 380 mm of copper. Possible mechanisms of action include interference with sperm migration in the uterus and damage to or destruction of ova. It is FDA-approved for at least 10 years of use. The lack of any hormone in Paragard IUDs may make them attractive to women who do not wish to experience amenorrhea.

Nexplanon is a subdermal implant containing 68 mg of etonogestrel; it is approved for at least 3 years of use. It is the only LARC method that does not require a pelvic examination. Providers are required to complete a training course offered by the manufacturer to ensure proper placement and removal technique.

LARC should be a first-line birth control option

The primary indication for LARC is preg-nancy prevention. Because LARC methods are the most effective reversible means to prevent pregnancy—apart from complete abstinence from sexual intercourse—they should be offered as first-line birth control options to patients who do not wish to conceive. The ability to discontinue LARC methods is an attractive option for women who may want to become pregnant in the future, such as the patient in the opening vignette.

Efficacy rates are high

Because LARC methods do not require users to take action daily or prior to intercourse, they carry a risk of pregnancy of less than 1% (TABLE 1)4-7—equal to or better than rates seen with tubal sterilization. In comparison, the OC pill has a typical use contraceptive failure rate of about 8%.

LARC still has a low utilization rate

It is unfortunate that barriers to LARC methods remain in the United States (see, for example, “National organization identifies barriers to LARC,” above). As recently as 2011 to 2013, only 7.2% of US women aged 15 to 44 years used a LARC method.8 Provider inexperience and patient fears surrounding LARC use remain major barriers. In the past, nulliparity and young age were thought to be contraindications to IUD use. Research and experience have demonstrated, however, that IUDs and contraceptive implants are safe for use in young women and those who have not had children.

Cost barriers also have significantly limited the use of LARC methods. Over time, however, these contraceptives have become less costly to patients, and most insurance providers routinely cover LARC devices and insertion fees. The contraceptive mandate of the Affordable Care Act ensures coverage of contraception, including LARC, for interested women. These trends suggest continued improvement in women’s access to LARC.

National organization identifies barriers to LARC

In 2014, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), with support from Bayer Healthcare, organized a meeting of key opinion leaders to discuss ways to eliminate barriers to the most effective contraceptive methods, better known as long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). The resultant issue brief, Women’s Health: Approaches to improving unintended pregnancy rates in the United States, identified a number of key barriers:

- Financial and logistical obstacles. The consensus attendees agreed that LARC methods should be offered to all women not planning a pregnancy in the next 2 years, but acknowledged that operational or administrative process issues sometimes interfere with this goal. One of the most prominent of these issues was the lack of opportunity for same-day insertion of LARC. Other issues included the cost to stock LARC methods, a lack of understanding of billing and reimbursement for LARC, reimbursement policies that prohibit billing for the visit and placement on the same day, and an overabundance of paperwork.

- Timing of the contraceptive counseling session. Many women fail to return for the 6-week postpartum visit—the visit typically set aside for counseling about contraception.

- Lack of a quality measure that would “motivate change in clinical practice.”1 One option: Treat family planning as a “vital sign” that needs to be addressed during the annual visit. “This would lead to stronger evidence for effecting change,” the report notes.1

- Lack of adequate communication skills by the provider. According to the NCQA report, “There are strong positive relationships between a health care team member’s communication skills and a patient’s willingness to follow through with medical recommendations.”1 The establishment of a “current counseling approach” that emphasizes the efficiency and effectiveness of LARC methods as well as the tremendous impact an unintended pregnancy would have on a woman’s whole life course would help improve provider-patient communication and increase the likelihood of LARC methods being utilized.1

- Lack of receptivity among some patients. For some women, the person delivering the message is as important as the message itself, depending on social and cultural norms. Sensitivity of health care providers to these nuances of communication can help enhance patient receptivity to the key message. As the NCQA report notes, “Physicians and the health care system are not always the most trusted source of information, and understanding disparities in contraception care will be important in changing patient behavior.”1

- Basic issues such as cost and access to care.1 Not all women are covered by insurance, particularly in states that opted against expanding access to Medicaid. For these women, the cost of LARC methods and insertion may be prohibitive.

Reference

Noncontraceptive benefits include reduced bleeding

The 3 LNG-IUS methods and the subdermal implant offer several benefits beyond contraception. Because of their progestin content, these methods reduce or even eliminate menses. This benefit can be very helpful for women who experience heavy menstrual periods and the consequent risk of anemia. Because of reduced menstrual flow, users of hormonal LARC methods also commonly experience less cramping associated with menses.

Women with endometriosis often benefit from hormonal LARC methods, as the disease is suppressed by the progestin component. Users of IUDs also have a reduced risk of endometrial cancer.

Contraindications to LARC

There are few contraindications to LARC methods, making them an appropriate choice for most women. The US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), contain guidelines that are based on the best available evidence.9 Contraceptive methods that are labeled as Category 1 or 2 are not contraindicated for most women. Methods that fall into Category 3 (theoretical or proven risks outweigh the advantages) or Category 4 (unacceptable health risk) are contraindicated (TABLE 2).9

IUDs once were thought to expose women to an increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, but this fear has long been disproven. Screening for chlamydia can be performed at the time of placement, as recommended annually for women younger than 25 years. Unless there is concern for active cervical or uterine infection, there is no need to delay insertion of an IUD while awaiting test results. In most cases, women found to have positive cultures after insertion can be treated successfully without IUD removal.

Main adverse effect is altered bleeding patterns

Adverse effects vary depending on the method being used. All LARC methods may affect menstrual patterns. For example, clinical trials involving the copper IUD indicate that abnormal heavy bleeding may lead to discontinuation in up to 10% of users.5,10 Amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea is uncommon with this method and rarely leads to discontinuation. For example, in one trial involving more than 900 women using a copper IUD for up to 5 years, there were no discontinuations due to amenorrhea. Dysmenorrhea may arise, but data from clinical trials indicate that its frequency decreases over time. In one trial, the frequency of any menstrual pain decreased from about 9% of users to 5% after 8 months or more of use.

The LNG-IUS also can be associated with abnormal uterine bleeding. In contrast to the copper IUD, LNG devices tend to reduce menstrual bleeding and can be unpredictable. Clinical trials involving the 5-year 52-mg LNG-IUS indicate that bleeding decreases over time, with as many as 70% of users developing amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea.5,11 However, some women using an LNG-IUS experience heavy bleeding— although the frequency of such bleeding tends to be substantially less than that experienced by copper IUD users.7

A lack of comparative trials makes it unclear whether the newer 3-year LNG-IUS devices are associated with a significantly altered bleeding pattern. Noncomparative data from the package insert for Skyla suggest that women using it may have a higher frequency of heavy menstrual bleeding and less amenorrhea than users of the 5-year device.6

Data from a 3-year clinical trial of the newest 52-mg LNG-IUS (Liletta) indicate that bleeding and dysmenorrhea led to discontinuation 1% to 2% of the time.2

Although the concentration of progestincirculating systemically is low with the various LNG-IUS devices, some women may experience symptoms such as mood swings, headaches, acne, and breast tenderness.

Expulsions during the first year of use of the copper IUD and the 3 LNG-IUS devices range from 2% to 10%, with the higher rates associated with immediate postpartum insertion.5

Uterine perforation has been reported in about 1 of every 1,000 insertions. Other adverse events are uncommon.

Clinical trials indicate that about 11% of implant users will discontinue the method due to bleeding abnormalities.12 About 25% to 30% of users will experience heavy or prolonged bleeding, while up to 33% will experience infrequent bleeding or amenorrhea. About 50% of implant users will experience improved bleeding patterns over time.

Other reasons for discontinuation of implant use in a very small percentage of users include emotional lability, weight gain, acne, and headaches.4 Complications due to insertion and removal are rare and include pain, bleeding, and hematoma formation.

Public health impact of LARC methods

An important question in regard to LARC use is: How do we best provide safe and effective contraception for teens and young adult women? There is increasing evidence that, with appropriate counseling and the removal of cost barriers, LARC methods can have a significant public health impact in this population.

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project, a cohort study in a teenage population of women in the St. Louis, Missouri, area, achieved increased utilization of LARC methods and significantly lower rates of pregnancy, birth, and abortion.13 Investigators proactively counseled young women about the advantages of LARC methods and offered them free of charge. As a result, 72% of women in the study chose an IUD or implant as their method of contraception. Pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates among participants were 34.0, 19.4, and 9.7 per 1,000 teens, respectively. By comparison, national statistics during the same time frame for pregnancy, birth, and abortion were 158.5, 94.0, and 41.5 per 1,000 US teens, respectively.13

A similar project in Colorado received $23.6 million in 2009 from an outside donor to make LARC methods more affordable to patients in family planning clinics in the state.14 Between 2009 and 2014, 30,000 contraceptive implants or IUDs were made available at low or no cost to low-income women attending 68 family planning clinics statewide. The use of these methods at participating clinics quadrupled. Further, the teen birth rate declined by 40% between 2009 and 2013—from 37 to 22 births per 1,000 teens.14 Seventy-five percent of this decline was attributable to increased use of these methods. The teen abortion rate declined by 35% in the same time frame.

In 2014, the Colorado governor’s office indicated that the state had saved $42.5 million in health care expenditures associated with teen births. It was estimated that, for every dollar spent on contraceptives, the state saved $5.68 in Medicaid costs. However, a bipartisan bill to continue funding the project has failed so far in 2015 due to concerns among some legislators that these methods—particularly the IUDs—are abortifacients. The reduced cost of the 3-year LNG-IUS (Liletta) and recent guidance from the US Department of Health and Human Services mandating that at least 1 form of contraception in each of the FDA-approved categories must be covered by insurers may help to overcome this barrier.

CASE: Resolved

You counsel the patient about the value of each LARC method, letting her know that they are all highly effective in the prevention of pregnancy. You also let her know how each method would affect her menstrual cycle and acknowledge that she may have a preference for whether the contraceptive is placed in her uterus or under the skin of her arm. She chooses the contraceptive implant, which you insert during the same visit. At a follow-up visit 6 weeks later, she reports satisfaction with the method.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE: Teen patient asks to switch contraceptive methods

A 17-year-old nulliparous woman comes to your clinic for an annual examination. She has no significant health problems, and her examination is normal. She notes that she was started on oral contraceptives (OCs) the year before because of heavy menstrual flow and a desire for birth control but has trouble remembering to take them—though she does usually use condoms. She asks your advice about switching to a different method but indicates that she has lost her health insurance coverage.

What can you offer her as an effective, low-cost contraceptive?

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods are especially suited for adolescent and young adult women, for whom daily compliance with a shorter-acting contraceptive may be problematic. Five LARC methods are available in the United States, including a new levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Liletta), which received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) this year. Like Mirena, Liletta contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel that is released over time. Liletta was introduced by the nonprofit organization Medicines360 and its commercial partner Actavis Pharma in response to evidence that poor women continue to lack access to LARC because of cost or problems with insurance coverage.1

For providers who practice in settings eligible for 340B pricing, Liletta costs $50, a fraction of the cost of alternative intrauterine devices (IUDs). The cost is slightly higher for non-340B providers but is still significantly lower than the cost of other IUDs. For health care practices, the reduced price of Liletta may make it feasible for them to offer LARC to more patients. The reduced pricing also makes Liletta an attractive option for women who choose to pay for the device directly rather than use insurance, such as the patient described above.

Patient experience with Liletta also is key. Not surprisingly, Liletta’s clinical trial found patient satisfaction to be similar to that of Mirena users.2 The failure rate is less than 1%, again comparable to Mirena. The rate of pelvic infection with Liletta use was 0.5%, also comparable to previously published data.3

One difference between Liletta and Mirena is that Liletta carries FDA approval for 3 years of contraceptive efficacy, compared with 5 years for Mirena. In order to make Liletta available to US patients now, Medicines360 decided to apply for 3-year contraceptive labeling while 5- and 7-year efficacy data are being collected. Like Mirena, Liletta is expected to provide excellent contraception for at least 5 years.

How to insert Liletta

- While still pinching the insertion tube, slide the tube through the cervical canal until the upper edge of the flange is approximately 1.5 to 2 cm from the cervix. Do not force the inserter. If necessary, dilate the cervical canal. Release your hold on the tenaculum.

- Hold the insertion tube with the fingers of one hand (Hand A) and the rod with the fingers of the other hand (Hand B).

- Holding the rod in place (Hand B), relax your pinch on the tube and pull the insertion tube back with Hand A to the edge of the second indent of the rod. This will allow the IUS arms to unfold in the lower uterine segment (FIGURE). Wait 10 to 15 seconds for the arms of the IUS to open fully.

- Apply gentle traction with the tenaculum before advancing the IUS. With Hand A still holding the proximal end of the tube, advance both the insertion tube and rod simultaneously up to the uterine fundus. You will feel slight resistance when the IUS is at the fundus. Make sure the flange is touching the cervix when the IUS reaches the uterine fundus. Fundal positioning is important to prevent expulsion.

- Hold the rod still (Hand B) while pulling the insertion tube back with Hand A to the ring of the rod. While holding the inserter tube with Hand A, withdraw the rod from the insertion tube all of the way out to prevent the rod from catching on the knot at the lower end of the IUS. Completely remove the insertion tube.

- Using blunt-tipped sharp scissors, cut the IUS threads perpendicular to the thread length, leaving about 3 cm outside of the cervix. Do not apply tension or pull on the threads when cutting to prevent displacing the IUS. Insertion is now complete.

Source: Liletta [package insert]. Actavis Pharma, Parsippany, NJ; 2015.

Skyla is another LARC option for womenseeking an LNG-IUS for contraception. It provides highly effective contraception for at least 3 years through the release of 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel over time. Skyla’s reduced levonorgestrel content, as compared with Mirena and Liletta, means that fewer users will experience amenorrhea (13% vs 25%).

Paragard is a nonhormonal IUD that uses copper for contraceptive efficacy. The device contains a total of 380 mm of copper. Possible mechanisms of action include interference with sperm migration in the uterus and damage to or destruction of ova. It is FDA-approved for at least 10 years of use. The lack of any hormone in Paragard IUDs may make them attractive to women who do not wish to experience amenorrhea.

Nexplanon is a subdermal implant containing 68 mg of etonogestrel; it is approved for at least 3 years of use. It is the only LARC method that does not require a pelvic examination. Providers are required to complete a training course offered by the manufacturer to ensure proper placement and removal technique.

LARC should be a first-line birth control option

The primary indication for LARC is preg-nancy prevention. Because LARC methods are the most effective reversible means to prevent pregnancy—apart from complete abstinence from sexual intercourse—they should be offered as first-line birth control options to patients who do not wish to conceive. The ability to discontinue LARC methods is an attractive option for women who may want to become pregnant in the future, such as the patient in the opening vignette.

Efficacy rates are high

Because LARC methods do not require users to take action daily or prior to intercourse, they carry a risk of pregnancy of less than 1% (TABLE 1)4-7—equal to or better than rates seen with tubal sterilization. In comparison, the OC pill has a typical use contraceptive failure rate of about 8%.

LARC still has a low utilization rate

It is unfortunate that barriers to LARC methods remain in the United States (see, for example, “National organization identifies barriers to LARC,” above). As recently as 2011 to 2013, only 7.2% of US women aged 15 to 44 years used a LARC method.8 Provider inexperience and patient fears surrounding LARC use remain major barriers. In the past, nulliparity and young age were thought to be contraindications to IUD use. Research and experience have demonstrated, however, that IUDs and contraceptive implants are safe for use in young women and those who have not had children.

Cost barriers also have significantly limited the use of LARC methods. Over time, however, these contraceptives have become less costly to patients, and most insurance providers routinely cover LARC devices and insertion fees. The contraceptive mandate of the Affordable Care Act ensures coverage of contraception, including LARC, for interested women. These trends suggest continued improvement in women’s access to LARC.

National organization identifies barriers to LARC

In 2014, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), with support from Bayer Healthcare, organized a meeting of key opinion leaders to discuss ways to eliminate barriers to the most effective contraceptive methods, better known as long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). The resultant issue brief, Women’s Health: Approaches to improving unintended pregnancy rates in the United States, identified a number of key barriers:

- Financial and logistical obstacles. The consensus attendees agreed that LARC methods should be offered to all women not planning a pregnancy in the next 2 years, but acknowledged that operational or administrative process issues sometimes interfere with this goal. One of the most prominent of these issues was the lack of opportunity for same-day insertion of LARC. Other issues included the cost to stock LARC methods, a lack of understanding of billing and reimbursement for LARC, reimbursement policies that prohibit billing for the visit and placement on the same day, and an overabundance of paperwork.

- Timing of the contraceptive counseling session. Many women fail to return for the 6-week postpartum visit—the visit typically set aside for counseling about contraception.

- Lack of a quality measure that would “motivate change in clinical practice.”1 One option: Treat family planning as a “vital sign” that needs to be addressed during the annual visit. “This would lead to stronger evidence for effecting change,” the report notes.1

- Lack of adequate communication skills by the provider. According to the NCQA report, “There are strong positive relationships between a health care team member’s communication skills and a patient’s willingness to follow through with medical recommendations.”1 The establishment of a “current counseling approach” that emphasizes the efficiency and effectiveness of LARC methods as well as the tremendous impact an unintended pregnancy would have on a woman’s whole life course would help improve provider-patient communication and increase the likelihood of LARC methods being utilized.1

- Lack of receptivity among some patients. For some women, the person delivering the message is as important as the message itself, depending on social and cultural norms. Sensitivity of health care providers to these nuances of communication can help enhance patient receptivity to the key message. As the NCQA report notes, “Physicians and the health care system are not always the most trusted source of information, and understanding disparities in contraception care will be important in changing patient behavior.”1

- Basic issues such as cost and access to care.1 Not all women are covered by insurance, particularly in states that opted against expanding access to Medicaid. For these women, the cost of LARC methods and insertion may be prohibitive.

Reference

Noncontraceptive benefits include reduced bleeding

The 3 LNG-IUS methods and the subdermal implant offer several benefits beyond contraception. Because of their progestin content, these methods reduce or even eliminate menses. This benefit can be very helpful for women who experience heavy menstrual periods and the consequent risk of anemia. Because of reduced menstrual flow, users of hormonal LARC methods also commonly experience less cramping associated with menses.

Women with endometriosis often benefit from hormonal LARC methods, as the disease is suppressed by the progestin component. Users of IUDs also have a reduced risk of endometrial cancer.

Contraindications to LARC

There are few contraindications to LARC methods, making them an appropriate choice for most women. The US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), contain guidelines that are based on the best available evidence.9 Contraceptive methods that are labeled as Category 1 or 2 are not contraindicated for most women. Methods that fall into Category 3 (theoretical or proven risks outweigh the advantages) or Category 4 (unacceptable health risk) are contraindicated (TABLE 2).9

IUDs once were thought to expose women to an increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, but this fear has long been disproven. Screening for chlamydia can be performed at the time of placement, as recommended annually for women younger than 25 years. Unless there is concern for active cervical or uterine infection, there is no need to delay insertion of an IUD while awaiting test results. In most cases, women found to have positive cultures after insertion can be treated successfully without IUD removal.

Main adverse effect is altered bleeding patterns

Adverse effects vary depending on the method being used. All LARC methods may affect menstrual patterns. For example, clinical trials involving the copper IUD indicate that abnormal heavy bleeding may lead to discontinuation in up to 10% of users.5,10 Amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea is uncommon with this method and rarely leads to discontinuation. For example, in one trial involving more than 900 women using a copper IUD for up to 5 years, there were no discontinuations due to amenorrhea. Dysmenorrhea may arise, but data from clinical trials indicate that its frequency decreases over time. In one trial, the frequency of any menstrual pain decreased from about 9% of users to 5% after 8 months or more of use.

The LNG-IUS also can be associated with abnormal uterine bleeding. In contrast to the copper IUD, LNG devices tend to reduce menstrual bleeding and can be unpredictable. Clinical trials involving the 5-year 52-mg LNG-IUS indicate that bleeding decreases over time, with as many as 70% of users developing amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea.5,11 However, some women using an LNG-IUS experience heavy bleeding— although the frequency of such bleeding tends to be substantially less than that experienced by copper IUD users.7

A lack of comparative trials makes it unclear whether the newer 3-year LNG-IUS devices are associated with a significantly altered bleeding pattern. Noncomparative data from the package insert for Skyla suggest that women using it may have a higher frequency of heavy menstrual bleeding and less amenorrhea than users of the 5-year device.6

Data from a 3-year clinical trial of the newest 52-mg LNG-IUS (Liletta) indicate that bleeding and dysmenorrhea led to discontinuation 1% to 2% of the time.2

Although the concentration of progestincirculating systemically is low with the various LNG-IUS devices, some women may experience symptoms such as mood swings, headaches, acne, and breast tenderness.

Expulsions during the first year of use of the copper IUD and the 3 LNG-IUS devices range from 2% to 10%, with the higher rates associated with immediate postpartum insertion.5

Uterine perforation has been reported in about 1 of every 1,000 insertions. Other adverse events are uncommon.

Clinical trials indicate that about 11% of implant users will discontinue the method due to bleeding abnormalities.12 About 25% to 30% of users will experience heavy or prolonged bleeding, while up to 33% will experience infrequent bleeding or amenorrhea. About 50% of implant users will experience improved bleeding patterns over time.

Other reasons for discontinuation of implant use in a very small percentage of users include emotional lability, weight gain, acne, and headaches.4 Complications due to insertion and removal are rare and include pain, bleeding, and hematoma formation.

Public health impact of LARC methods

An important question in regard to LARC use is: How do we best provide safe and effective contraception for teens and young adult women? There is increasing evidence that, with appropriate counseling and the removal of cost barriers, LARC methods can have a significant public health impact in this population.

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project, a cohort study in a teenage population of women in the St. Louis, Missouri, area, achieved increased utilization of LARC methods and significantly lower rates of pregnancy, birth, and abortion.13 Investigators proactively counseled young women about the advantages of LARC methods and offered them free of charge. As a result, 72% of women in the study chose an IUD or implant as their method of contraception. Pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates among participants were 34.0, 19.4, and 9.7 per 1,000 teens, respectively. By comparison, national statistics during the same time frame for pregnancy, birth, and abortion were 158.5, 94.0, and 41.5 per 1,000 US teens, respectively.13

A similar project in Colorado received $23.6 million in 2009 from an outside donor to make LARC methods more affordable to patients in family planning clinics in the state.14 Between 2009 and 2014, 30,000 contraceptive implants or IUDs were made available at low or no cost to low-income women attending 68 family planning clinics statewide. The use of these methods at participating clinics quadrupled. Further, the teen birth rate declined by 40% between 2009 and 2013—from 37 to 22 births per 1,000 teens.14 Seventy-five percent of this decline was attributable to increased use of these methods. The teen abortion rate declined by 35% in the same time frame.

In 2014, the Colorado governor’s office indicated that the state had saved $42.5 million in health care expenditures associated with teen births. It was estimated that, for every dollar spent on contraceptives, the state saved $5.68 in Medicaid costs. However, a bipartisan bill to continue funding the project has failed so far in 2015 due to concerns among some legislators that these methods—particularly the IUDs—are abortifacients. The reduced cost of the 3-year LNG-IUS (Liletta) and recent guidance from the US Department of Health and Human Services mandating that at least 1 form of contraception in each of the FDA-approved categories must be covered by insurers may help to overcome this barrier.

CASE: Resolved

You counsel the patient about the value of each LARC method, letting her know that they are all highly effective in the prevention of pregnancy. You also let her know how each method would affect her menstrual cycle and acknowledge that she may have a preference for whether the contraceptive is placed in her uterus or under the skin of her arm. She chooses the contraceptive implant, which you insert during the same visit. At a follow-up visit 6 weeks later, she reports satisfaction with the method.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Dehlendorf C, Rodriguez MI, Levy K, Borrero S, Steinauer J.Disparities in family planning. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):214–220.

2. Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92(1):10–16.

3. Sufrin C, Postlethwaite D, Armstrong MA, et al. Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis screening at intrauterine device insertion and pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1314–1321.

4. Espey E, Ogburn T. Long-acting reversible contraceptives—intrauterine devices and the contraceptive implant. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):705–719.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):184–196.

6. Skyla [package insert]. Bayer Healthcare, Wayne, NJ; 2013.

7. Liletta [package insert]. Actavis Pharma, Parsippany, NJ; 2015.

8. Branum AM, Jones J. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: NCHS Data Brief No. 188: Trends in Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Use Among US Women Aged 15–44. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db188.htm. Published February 2015. Accessed August 14, 2015.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR4):1–86.

10. Andersson K, Odlind VL, Rybo G. Levonorgestrel-releasing and copper-releasing (Nova T) IUDs during five years of use; a randomized comparative trial. Contraception. 1994;49(1):56–72.

11. Sivin I, Stern J, Diaz J, et al. Two years of intrauterine contraception with levonorgestrel and copper: a randomized comparison of the TCu 380Ag and levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day devices. Contraception. 1987;35(3):245–255.

12. Mansour F, Korver T, Marintcheva-Petrova M, Fraser IS. The effects of Implanon on menstrual bleeding patterns. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13(suppl 1):13–28.

13. Secura GM, Madden T, McNicholas C, et al. Provision of no-cost, long-acting contraception and teenage pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1316–1323.

14. Tavernise S. Colorado’s effort against teenage pregnancies is a startling success. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/06/science/colorados-push-against-teenage-pregnancies-is-a-startling-success.html. Published July 6, 2015. Accessed August 17, 2015.

1. Dehlendorf C, Rodriguez MI, Levy K, Borrero S, Steinauer J.Disparities in family planning. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):214–220.

2. Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92(1):10–16.

3. Sufrin C, Postlethwaite D, Armstrong MA, et al. Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis screening at intrauterine device insertion and pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1314–1321.

4. Espey E, Ogburn T. Long-acting reversible contraceptives—intrauterine devices and the contraceptive implant. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):705–719.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):184–196.

6. Skyla [package insert]. Bayer Healthcare, Wayne, NJ; 2013.

7. Liletta [package insert]. Actavis Pharma, Parsippany, NJ; 2015.

8. Branum AM, Jones J. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: NCHS Data Brief No. 188: Trends in Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Use Among US Women Aged 15–44. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db188.htm. Published February 2015. Accessed August 14, 2015.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR4):1–86.

10. Andersson K, Odlind VL, Rybo G. Levonorgestrel-releasing and copper-releasing (Nova T) IUDs during five years of use; a randomized comparative trial. Contraception. 1994;49(1):56–72.

11. Sivin I, Stern J, Diaz J, et al. Two years of intrauterine contraception with levonorgestrel and copper: a randomized comparison of the TCu 380Ag and levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day devices. Contraception. 1987;35(3):245–255.

12. Mansour F, Korver T, Marintcheva-Petrova M, Fraser IS. The effects of Implanon on menstrual bleeding patterns. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13(suppl 1):13–28.

13. Secura GM, Madden T, McNicholas C, et al. Provision of no-cost, long-acting contraception and teenage pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1316–1323.

14. Tavernise S. Colorado’s effort against teenage pregnancies is a startling success. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/06/science/colorados-push-against-teenage-pregnancies-is-a-startling-success.html. Published July 6, 2015. Accessed August 17, 2015.

In this Article

- A comparative look at 5 LARC methods

- Common barriers to LARC

- How to insert Liletta

Dr. Robert L. Barbieri's Editors Picks for January 2015

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Click here for the rest of January 2015 issue.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Click here for the rest of January 2015 issue.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Click here for the rest of January 2015 issue.

STOP all activities that may lead to further shoulder impaction when you suspect possible shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia is an obstetric complication that occurs in up to 1.4% of deliveries.1 Although the vast majority can be managed successfully, the complication is associated with risk of fetal injury. The most serious injury is brachial plexus palsy, which occurs in 4% to 40% of shoulder dystocia cases, although less than 10% of these injuries are permanent. Other injuries include fractures of the clavicle and humerus; in rare instances the complication may be associated with fetal asphyxia and death. Early recognition of the complication followed by an orderly approach to management will reduce the risk of fetal injury.

First, recognize shoulder dystocia and take control

Recognition of shoulder dystocia immediately followed by avoidance of further impaction, particularly of the anterior shoulder against the symphysis pubis, will likely increase the chances of successful resolution.

These factors should lead you to anticipate shoulder dystocia during delivery:

- suspected macrosomia

- diabetic parturient

- prolonged second stage.

However, a high percentage of cases occur in women without risk factors. Because persistent or forceful traction, used in an attempt to deliver the anterior shoulder, may be one of the causes of brachial plexus injury, early recognition of shoulder dystocia, followed by a halt of further traction, reduces the risk of that injury.

In my experience, if some movement of the anterior shoulder does not occur after 2 to 3 seconds of gentle downward guidance, you need to consider the possibility of shoulder dystocia. It is also important to take control of the situation: Instruct the patient to stop pushing and family members to stop urging the patient to push.

Click here to read 5 recent articles on shoulder dystocia

Avoid panic. Initiate a care-team management algorithm.

Having a management algorithm that can be quickly recalled and initiated allows the care team to proceed in an orderly fashion and remain calm and avoid panic, particularly if the dystocia is severe. In obstetric emergencies, panic is your enemy, leading to inefficient activity, team confusion, and an increased likelihood that an error in judgment (too much traction, fundal pressure) may occur. I advise my residents that whenever there are risk factors for shoulder dystocia, or it is suspected for any reason, to do a mental run-through of the management steps.

Rehearse the algorithm. It will make a difference in the delivery room.

To most effectively use a management algorithm, rehearsal using team training drills or simulation is necessary. Studies support simulation and team training even for individuals who have completed training in obstetrics or midwifery. Crofts and colleagues videotaped 450 simulations of shoulder dystocia involving 95 certified nurse midwives and 45 physicians.2 The authors noted that 1) shoulder dystocia could not be resolved in 57% of cases, and 2) there was frequent confusion regarding how to perform the internal maneuvers, with poor communication among team members. This same group of researchers later demonstrated that skills in managing shoulder dystocia improved significantly after simulation training. In fact, a high proportion of “trainees” maintained their skill level when tested a year later.3

Finally, when evaluating the impact of training on actual clinical outcomes in their hospital, Crofts and colleagues noted that the rate of obstetric brachial plexus injury fell from 7.4% in a 4-year period prior to training, to 2.3% in a 4-year period after training.4

Practice within your own L&D unit

The use of in situ simulation (ie, simulation within the labor and delivery unit) has two major advantages:

- It is more realistic than practicing within a lab. Systems issues, such as lack of a uniform procedure for getting help or a lack of chairs in the labor room to assist with performance of suprapubic pressure, can be identified.

- The full team, including ward clerks and other support personnel, can be part of the simulation more readily.

The box on this page provides a possible process to use in managing shoulder dystocia. If there has not been an opportunity for this training, practitioners, at the very least, should be cognizant of the steps they are going to take in managing such cases.

- Recognition of shoulder dystocia

- Stop bearing down and stop traction

- Communicate with staff and patient

- Call for help and begin timekeeping

- Initiate the McRoberts maneuver*

- Suprapubic pressure (may be combined with Rubin’s maneuver, pushing on anterior or posterior shoulder to rotate to an oblique position)*

- Attempt delivery of posterior arm (episiotomy can be performed at this step, if needed)*,**

- Woods screw or Rubin’s maneuver*,**

- Repeat above steps if delivery not accomplished

- Gaskin (all fours) maneuver*

- Zavanelli maneuver and cesarean delivery

- Document event and communicate with patient and family (use of checklists such as the one published by ACOG may help standardize the process)

* The patient can resume bearing down and the clinician can use gentle downward guidance after performing the maneuver. If there is no progress, continue to the next maneuver.

** Order of performance of secondary maneuvers may vary, although Gaskin maneuver may be best carried out near the end due to the need for repositioning and possible reduced patient mobility due to epidural anesthesia.

What should you do after primary maneuvers fail?

Try to deliver the posterior arm. Although the order of maneuvers in the proposed algorithm may vary, a recent study using a database of more than 130,000 deliveries suggests that use of posterior arm delivery after failure of primary maneuvers, such as McRoberts or suprapubic pressure, may more likely result in resolution.5

Start from the beginning, and try again. If the first set of maneuvers does not resolve the problem, running through them again usually leads to success. Although the risk of fetal hypoxia increases the longer it takes to resolve the dystocia, it may actually facilitate delivery because fetal tone may also decrease.

Zavanelli maneuver. In general, use of the Zavanelli maneuver with replacement of the fetal head accompanied by cesarean section is a last resort; there is a lack of data to support its use earlier in the process or more frequently. This maneuver requires reversing the cardinal movements related to head descent in order to successfully complete replacement.

Shoulder dystocia in obese patients proves more difficult

In my own experience with obese patients, suprapubic pressure is often ineffective due to the presence of a large fat pad or pannus. Use of an anterior Rubin’s maneuver to rotate the shoulders about 30° to the oblique often facilitates delivery.

Liberal use of episiotomy to facilitate posterior arm delivery or rotational maneuvers is often necessary with obese patients.

Documentation is key

Documentation of the dystocia event in the patient’s permanent record should not occur until after the care team has discussed the case. This will ensure that the maneuvers utilized and the related timing of events are recorded accurately. This is critically important should a lawsuit occur, since discrepancies or errors in charting will hamper defense of the case. A checklist, such as the one provided by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, lists key points that should be recorded and outlines important steps related to the event.6

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Most of our monthly Medical Verdicts columns include cases about shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injury, or Erb’s palsy. CLICK HERE to read those from 2012 and 2013.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 40: Shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(5 Part 1):1045-1050.

2. Crofts JF, Fox R, Ellis D, Winter C, Hinshaw K, Draycott TJ. Observations from 450 shoulder dystocia simulations: lessons for skills training. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):906-912.

3. Crofts JF, Bartlett C, Ellis D, Hunt LP, Fox R, Draycott TJ. Management of shoulder dystocia: skill retention 6 and 12 months after training. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(5):1069-1074.

4. Draycott TJ, Crofts JF, Ash JP, et al. Improving neonatal outcome through practical shoulder dystocia training. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):14-20.

5. Hoffman MK, Bailit JL, Branch DW, et al. Consortium on Safe Labor. A comparison of obstetric maneuvers for the acute management of shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1272-1278.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Patient Safety Checklist, Number 6: Documenting shoulder dystocia. http://www.acog.org/Resources_And_Publications/Patient_Safety_Checklists. Published August 2012. Accessed February 12, 2013.

Shoulder dystocia is an obstetric complication that occurs in up to 1.4% of deliveries.1 Although the vast majority can be managed successfully, the complication is associated with risk of fetal injury. The most serious injury is brachial plexus palsy, which occurs in 4% to 40% of shoulder dystocia cases, although less than 10% of these injuries are permanent. Other injuries include fractures of the clavicle and humerus; in rare instances the complication may be associated with fetal asphyxia and death. Early recognition of the complication followed by an orderly approach to management will reduce the risk of fetal injury.

First, recognize shoulder dystocia and take control

Recognition of shoulder dystocia immediately followed by avoidance of further impaction, particularly of the anterior shoulder against the symphysis pubis, will likely increase the chances of successful resolution.

These factors should lead you to anticipate shoulder dystocia during delivery:

- suspected macrosomia

- diabetic parturient

- prolonged second stage.

However, a high percentage of cases occur in women without risk factors. Because persistent or forceful traction, used in an attempt to deliver the anterior shoulder, may be one of the causes of brachial plexus injury, early recognition of shoulder dystocia, followed by a halt of further traction, reduces the risk of that injury.

In my experience, if some movement of the anterior shoulder does not occur after 2 to 3 seconds of gentle downward guidance, you need to consider the possibility of shoulder dystocia. It is also important to take control of the situation: Instruct the patient to stop pushing and family members to stop urging the patient to push.

Click here to read 5 recent articles on shoulder dystocia

Avoid panic. Initiate a care-team management algorithm.

Having a management algorithm that can be quickly recalled and initiated allows the care team to proceed in an orderly fashion and remain calm and avoid panic, particularly if the dystocia is severe. In obstetric emergencies, panic is your enemy, leading to inefficient activity, team confusion, and an increased likelihood that an error in judgment (too much traction, fundal pressure) may occur. I advise my residents that whenever there are risk factors for shoulder dystocia, or it is suspected for any reason, to do a mental run-through of the management steps.

Rehearse the algorithm. It will make a difference in the delivery room.

To most effectively use a management algorithm, rehearsal using team training drills or simulation is necessary. Studies support simulation and team training even for individuals who have completed training in obstetrics or midwifery. Crofts and colleagues videotaped 450 simulations of shoulder dystocia involving 95 certified nurse midwives and 45 physicians.2 The authors noted that 1) shoulder dystocia could not be resolved in 57% of cases, and 2) there was frequent confusion regarding how to perform the internal maneuvers, with poor communication among team members. This same group of researchers later demonstrated that skills in managing shoulder dystocia improved significantly after simulation training. In fact, a high proportion of “trainees” maintained their skill level when tested a year later.3

Finally, when evaluating the impact of training on actual clinical outcomes in their hospital, Crofts and colleagues noted that the rate of obstetric brachial plexus injury fell from 7.4% in a 4-year period prior to training, to 2.3% in a 4-year period after training.4

Practice within your own L&D unit

The use of in situ simulation (ie, simulation within the labor and delivery unit) has two major advantages:

- It is more realistic than practicing within a lab. Systems issues, such as lack of a uniform procedure for getting help or a lack of chairs in the labor room to assist with performance of suprapubic pressure, can be identified.

- The full team, including ward clerks and other support personnel, can be part of the simulation more readily.

The box on this page provides a possible process to use in managing shoulder dystocia. If there has not been an opportunity for this training, practitioners, at the very least, should be cognizant of the steps they are going to take in managing such cases.

- Recognition of shoulder dystocia

- Stop bearing down and stop traction

- Communicate with staff and patient

- Call for help and begin timekeeping

- Initiate the McRoberts maneuver*

- Suprapubic pressure (may be combined with Rubin’s maneuver, pushing on anterior or posterior shoulder to rotate to an oblique position)*

- Attempt delivery of posterior arm (episiotomy can be performed at this step, if needed)*,**

- Woods screw or Rubin’s maneuver*,**

- Repeat above steps if delivery not accomplished

- Gaskin (all fours) maneuver*

- Zavanelli maneuver and cesarean delivery

- Document event and communicate with patient and family (use of checklists such as the one published by ACOG may help standardize the process)