User login

The Rosacea Patient Journey: A Novel Approach to Conceptualizing Patient Experiences

Rosacea patients experience symptoms ranging from flushing to persistent acnelike rashes that can cause low self-esteem and anxiety, leading to social and professional isolation.1 Although it is estimated that 16 million individuals in the United States have rosacea, only 10% seek treatment.2,3 The motivation for patients to seek and adhere to treatment is not well characterized.

A patient journey is a map of the steps a patient takes as he/she progresses through different segments of the disease from diagnosis to management, including all the influences that can push him/her toward or away from certain decisions. The patient journey model provides a structure for understanding key issues in rosacea management, including barriers to successful treatment outcomes.

The patient journey model progresses from development of disease and diagnosis to treatment and disease management (Figure). We sought to examine each step of the rosacea patient journey to better understand key patient care boundaries faced by rosacea patients. We assessed the current literature regarding each step of the patient experience and identified areas of the patient journey with limited research.

Click here to view the figure as a PDF to print for future reference.

Researching the Patient Experience

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a search of the National Rosacea Society Web site (http://www.rosacea.org) were conducted to identify articles and materials that quantitatively or qualitatively described rosacea patient experiences. Search terms included rosacea, rosacea patient experience, rosacea treatment, rosacea adherence, and rosacea quality of life. A Google search also was conducted using the same terms to obtain current news articles online. Current literature pertaining to the patient journey was summarized.

To create a model for the rosacea patient journey, we refined a rheumatoid arthritis patient journey map4 and included the critical components of the journey for rosacea patients. We organized the journey into stages, including prediagnosis, diagnosis, treatment, adherence, and management. We first explored what occurs prior to diagnosis, which includes the patient’s symptoms before visiting a physician. We then examined the process of diagnosis and the implementation of a treatment plan. Treatment adherence was then explored, ending with the ways patients self-manage their disease beyond the physician’s office.

Prediagnosis: What Motivates Patients to Seek Treatment

Rosacea can present with many symptoms that may lead patients to see a physician, including facial erythema and telangiectases, papules and pustules, phymatous changes, and ocular manifestations.5 The most common concern is temporary facial flushing, followed by persistent redness, then bumps and pimples.6 Many patients seek treatment after persistent facial flushing and an intolerable burning sensation. Some middle-aged patients decide to see a dermatologist for the first time when they break out in acne lesions after a history of clear skin. Others seek treatment because they can no longer tolerate the pain and embarrassment associated with their symptoms. However, patients who seek treatment only account for a small proportion of patients with rosacea, as only 10% of patients seek conventional medical treatment.7 Furthermore, symptomatic patients on average wait 7 months to 5 years before receiving a diagnosis.8,9

Care often is delayed or not pursued because many rosacea symptoms are mild when they first appear and may not initially bother the patient. Patients may not think anything of their symptoms and dismiss them as either acne vulgaris or sunburn. Due to the relapsing and remitting nature of the disease course, patients may feel their symptoms will resolve. Of patients diagnosed with rosacea, only one-half have heard of the condition prior to diagnosis,8 which can largely be attributed to lack of patient education on the signs and symptoms of rosacea, a concern that prompted the National Rosacea Society to designate the month of April as rosacea awareness month.5

With sales of antiredness facial care products growing 35% from 2002 to 2007, accounting for an increase of $300 million in revenue, patients also may be turning to over-the-counter products first.10 Men with rosacea tend to present with more severe symptoms such as rhinophyma, which may be due to their desire to wait until their symptoms reached more advanced stages of disease before seeking medical help.5

Diagnosis of Rosacea

After the patient decides that his/her symptoms are unusual, severe, or intolerable enough to seek treatment, the issues of access to dermatologic care and receiving the correct diagnosis come into play. Accessing dermatologic care can be difficult, as appointments may be hard to obtain, and even if the patient is able to get an appointment, it could be many weeks later.11 For some rosacea patients, the anxiety of waiting for their appointment prompts them to seek support and advice from online message boards (eg, http://www.rosacea-support.org). The long wait for appointments may be attributed to the increased demand for dermatologists for cosmetic procedures.12 Additionally, disparities according to insurance type can contribute to difficulties procuring an appointment. In one study, privately insured dermatology patients demonstrated a 91% acceptance rate and shorter wait times for appointments compared to publicly insured patients who were limited to a 29.8% acceptance rate and longer wait times.11 Many patients then are left to wait for an appointment with a dermatologist or instead turn to a primary care physician. Of patients diagnosed with rosacea in one study (N=2847), the majority of patients were seen by a dermatologist (79%), while the other patients were diagnosed by a family physician (14%) or other types of physicians such as internists and ophthalmologists (7%).6

The diagnosis of rosacea usually is not a major hurdle for dermatologists, but misdiagnoses can sometimes occur. The Rosacea Research & Development Institute compiled multiple patient anecdotes describing the struggles of finally reaching the correct diagnosis of rosacea; however, no estimates as to the frequency of misdiagnoses was estimated.13 Even with an accurate diagnosis of rosacea, correct classification of the 4 types of rosacea (ie, erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, ocular) is necessary to avoid incorrect treatment recommendations. For example, patients with flushing often cannot tolerate topical medications in contrast to patients with the papulopustular subtype who benefit from them.14 In the meantime, the patients who are misdiagnosed may be met with frustration, as treatment was either delayed or incorrectly prescribed.

Although there are limited data regarding patient reactions after receiving a diagnosis of rosacea, it can be assumed that patients would be hopeful that diagnosis would lead to correct treatment. In a 2008 article in The New York Times, a rosacea patient was described as feeling relieved to be diagnosed with rosacea because it was an explanation for the development of pimples on the cheeks in her late 40s.10

Implementation of a Treatment Plan

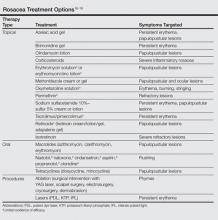

After recognizing the symptoms and receiving a correct diagnosis, the next step in the patient journey is treatment. Long-term management of incurable conditions such as rosacea is difficult. The main goals of treatment are to relieve symptoms, improve appearance, delay progression to advanced stages, and maintain remission.15 There are only a few reliable clinical trials regarding therapies for rosacea, so treatment has mostly relied on clinical experience (Table). The efficacy and safety of many older treatments has not been assessed.15 Mainstays of treatment include both topical agents and oral medications. The use of topical metronidazole, oral tetracycline, and oral isotretinoin have been found to improve both skin lesions and quality of life.18 Initially, a combination of a topical and an oral medication may be used for at least the first 12 weeks, and improvement is usually gradual, taking many weeks to become evident.15 Long-term treatment with topical medications often is required for maintenance, which can last another 6 months or more.19,20

Besides using pharmacologic therapies, some patients also may choose to undergo various procedures. The most common procedure is laser therapy, followed by dermabrasion, chemical peels, hot loop electrocoagulation, and surgical sculpting or plastic surgery.6 The use of these adjunct therapies may suggest impatience from the patient for improvement; it also indicates the lengths patients will go to and willingness to pay for improvement of symptoms.

Along with medication, patients are recommended to make changes to their skin care regimen and lifestyle. Rosacea patients typically have sensitive skin that may include symptoms such as dryness, scaling, stinging, burning, and pruritus.16 Skin care recommendations for rosacea patients include using a gentle cleanser and regularly applying sunscreen.5 Issues with physical appearance can be addressed with the use of cosmetic products such as green-tinted makeup to conceal skin lesions.21 Remission can be maintained by identifying certain triggers (eg, red wine, spicy foods, extreme temperatures, prolonged sun exposure, vigorous exercise) that can cause flare-ups.15 The most common trigger is sun exposure, making photoprotection an important component of the rosacea patient’s skin care regimen.6

Adherence

With a diagnosis and treatment plan in effect, the patient journey reaches the stage of treatment adherence, which should include ongoing education about the condition. Self-reported statistics from rosacea patients indicated that 28% of patients took time off from their treatment regimen,6 but actual nonadherence rates likely are higher. The most commonly reported reason for poor treatment adherence among rosacea patients was the impression that the symptoms had resolved or were adequately controlled.6 Treatment also must be affordable. In a national survey of rosacea patients, 24% of 427 patients receiving pharmacologic therapy planned on switching medications because of cost, and 17% of 769 patients discontinued medications due to co-pay/insurance issues.6 Other reasons cited for discontinuation of treatment included patient perception that symptoms were not that serious, co-pay/insurance issues, ineffectiveness of the medication, and side effects.6 Adherence to topical medications is lower than oral medications due to the time and inconvenience required for application.22 For some patients, topical medications may be too messy, have a strange odor, or stain clothing.

It is promising that most rosacea patients have reported the intent to continue using pharmacologic agents because the medication prevented worsening of their symptoms.6 However, there are still patients who switch or discontinue therapies without physician direction. These patients often cite that they desire more information at the time of diagnosis, particularly related to causes of flare-ups, physical symptoms to expect, drug treatment options, makeup to cover up visible symptoms, surgical or laser treatment options, psychological symptoms, patient support groups, and counseling options.6

Management

The last part of the journey is disease management, which occurs when the patient learns how to control his/her symptoms long-term. Important factors contributing to long-term control of rosacea flares are medication adherence and avoiding lifestyle triggers.23,24 Through the other stages of the journey, the patient has learned which treatments work and which factors may lead to exacerbation of symptoms.

Educating Patients on the Journey

The patient journey is a concept that can be applied to any disease state and brings to light roadblocks that patients may face from the initial diagnosis to successful disease management. Rosacea patients are faced with confusing and aggravating symptoms that can cause anxiety and may lead them to seek treatment from a physician. Facial flushing and phymatous changes of the nose can be mistaken for alcohol abuse, leading rosacea to be a socially stigmatizing disease.15 Because rosacea involves mostly the facial skin, it can disrupt social and professional interactions, leading to quality-of-life effects such as difficulty functioning on a day-to-day basis, which can be detrimental because patients usually are aged 30 to 50 years and may be perceived based on their appearance in the workforce.3 A lack of confidence, low self-esteem, embarrassment, and anxiety can even lead to serious psychiatric conditions such as depression and body dysmorphic disorder.25 Because the severity of rosacea increases over time, it is important to educate patients about seeking early treatment; therefore, understanding and awareness of rosacea symptoms are necessary to prompt patients to see a medical professional to either confirm or refute the diagnosis.

Rosacea is a clinical diagnosis that relies on patterns of primary and secondary features, as outlined in a 2002 report by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea.5 Even with this consensus grading system, it appears that additional fine-tuning of the criteria is needed in the disease definition. Importantly, because much of the pathogenesis and progression of rosacea is still not completely understood, there is no laboratory benchmark test that can be utilized for correct diagnosis.14 Moreover, many of the clinical manifestations of rosacea are shared with other conditions, and patients may present with different symptoms or varying combinations.26

Treatment of rosacea is multifactorial and behavioral, as patients must not only be able to obtain and adhere to oral and topical regimens and possible procedures but also avoid various lifestyle and environmental triggers and learn to cope with emotional distress caused by their symptoms. Although patients who discontinue use of medications appear to be in the minority, education is still needed to stress the chronic nature of rosacea and the importance of the continuation of treatment. Collaboration between the physician and patient is needed to determine why a certain medication may not be effective and explore other treatment options. Treatment ineffectiveness could be due to incorrect use of the product, failure to use an adjunct skin care regimen, or inability to control rosacea triggers. Adequate early follow-up also is needed to maximize patient adherence to treatment.27 Working together with the patient to develop a treatment plan that can be followed is necessary for long-term control of rosacea symptoms.

There is little information on how to address the psychological needs of patients, but patients can find support from various avenues. For instance, the National Rosacea Society, a large advocacy group, produces newsletters and educational materials for both physicians and patients.28,29 There also are online support groups for rosacea patients that have thousands of members who exchange stories and provide words of encouragement. Although there are not many face-to-face support groups, physicians may consider developing live support groups for their rosacea patients. As patients achieve the later stages of the rosacea patient journey, they hopefully will have controlled their symptoms by following a treatment regimen and learning to adapt to a new life of successful disease management.

Many aspects of the rosacea patient journey have yet to be explored. It is uncertain how long patients with symptoms of rosacea wait before seeking treatment, what methods they use to control their rosacea before they receive a prescribed treatment or physician recommendations, and how they react to their diagnosis. It also is unknown how many rosacea patients receive an initial misdiagnosis of another condition and which physicians typically make the misdiagnosis. We also need to know more about the role of psychological issues in addressing patient adherence to treatment. Similarly, what role do support groups such as online forums play on adherence? There is a need for more patient education and awareness of rosacea.

Conclusion

Patients may be relieved that rosacea is not a life-threatening condition, but they may be disappointed that there is no cure for rosacea. As the patient and dermatologist work together to find an appropriate treatment plan, identify certain triggers, and modify the skin care routine, the patient can become disciplined in controlling rosacea symptoms. Ultimately, with the alleviation of visible symptoms, the patient’s quality of life also can improve. Better understanding of the rosacea patient perspective can lead to a more efficient health care system, improved patient care, and better patient satisfaction.

1. Baldwin HE. Systemic therapy for rosacea. Skin Therapy Lett. 2007;12:1-5, 9.

2. Drake L. Rosacea now estimated to affect at least 16 million Americans. Rosacea Review. Winter 2010. http://www.rosacea.org/rr/2010/winter/article_1.php. Accessed December 11, 2014.

3. Rosacea as an inflammatory disease: an expert interview with Brian Berman, MD, PhD. Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/722156. Published May 27, 2010. Accessed December 11, 2014.

4. HealthEd Group, Inc. Rheumatoid arthritis patient journey map. http://visual.ly/rheumatoid-arthritis-patient-journey-map. Accessed December 19, 2014.

5. Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

6. Elewski BE. Results of a national rosacea patient survey: common issues that concern rosacea sufferers. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:120-123.

7. Del Rosso J. Management of rosacea in the United States: analysis based on recent prescribing patterns and insurance claims. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:AB13.

8. New survey reveals first impressions may not always be rosy for people with the widespread skin condition rosacea. Medical News Today Web site. http://www.medicalnew today.com/releases/185491.php. Updated April 15, 2010. Accessed December 12, 2014.

9. Shear NH, Levine C. Needs survey of Canadian rosacea patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:178-181.

10. Sweeney C. In a perfect world, rosacea remains a problem. New York Times. April 24, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/24/fashion/24SKIN.html?pagewanted=all. Accessed December 12, 2014.

11. Alghothani L, Jacks SK, Vander HA, et al. Disparities in access to dermatologic care according to insurance type. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:956-957.

12. Resneck J Jr. Too few or too many dermatologists? difficulties in assessing optimal workforce size. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1295-1301.

13. Rosacea Research & Development Institute Web site. http://irosacea.org/misdiagnosed_rosacea.html. Accessed December 19, 2014.

14. Crawford GH, Pelle MT, James WD. Rosacea: I. etiology, pathogenesis, and subtype classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:327-341.

15. Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dreno B, et al. Rosacea—global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:188-200.

16. Del Rosso JQ, Baldwin H, Webster G. American Acne & Rosacea Society rosacea medical management guidelines. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:531-533.

17. Fowler J Jr, Jackson M, Moore A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, and vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:650-656.

18. Aksoy B, Altaykan-Hapa A, Egemen D, et al. The impact of rosacea on quality of life: effects of demographic and clinical characteristics and various treatment modalities. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:719-725.

19. Dahl MV, Katz HI, Krueger GG, et al. Topical metronidazole maintains remissions of rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:679-683.

20. Thiboutot DM, Fleischer AB, Del Rosso JQ, et al. A multicenter study of topical azelaic acid 15% gel in combination with oral doxycycline as initial therapy and azelaic acid 15% gel as maintenance monotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:639-648.

21. Boehncke WH, Ochsendorf F, Paeslack I, et al. Decorative cosmetics improve the quality of life in patients with disfiguring skin diseases. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:577-580.

22. Jackson JM, Pelle M. Topical rosacea therapy: the importance of vehicles for efficacy, tolerability and compliance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:627-633.

23. Wolf JE Jr. Medication adherence: a key factor in effective management of rosacea. Adv Ther. 2001;18:272-281.

24. Managing rosacea. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/patients/materials/managing/lifestyle.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

25. van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Lack of ‘appropriately assessed’ patient-reported outcomes in randomized controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of interventions for rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:442-444.

26. Del Rosso JQ. Advances in understanding and managing rosacea: part 2: the central role, evaluation, and medical management of diffuse and persistent facial erythema of rosacea. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:26-36.

27. Davis SA, Lin HC, Yu CH, et al. Underuse of early follow-up visits: a missed opportunity to improve patients’ adherence. 2014;13:833-836.

28. If you have rosacea, you’re not alone. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/patients/index.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

29. Tools for the professional. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/physicians/index.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

Rosacea patients experience symptoms ranging from flushing to persistent acnelike rashes that can cause low self-esteem and anxiety, leading to social and professional isolation.1 Although it is estimated that 16 million individuals in the United States have rosacea, only 10% seek treatment.2,3 The motivation for patients to seek and adhere to treatment is not well characterized.

A patient journey is a map of the steps a patient takes as he/she progresses through different segments of the disease from diagnosis to management, including all the influences that can push him/her toward or away from certain decisions. The patient journey model provides a structure for understanding key issues in rosacea management, including barriers to successful treatment outcomes.

The patient journey model progresses from development of disease and diagnosis to treatment and disease management (Figure). We sought to examine each step of the rosacea patient journey to better understand key patient care boundaries faced by rosacea patients. We assessed the current literature regarding each step of the patient experience and identified areas of the patient journey with limited research.

Click here to view the figure as a PDF to print for future reference.

Researching the Patient Experience

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a search of the National Rosacea Society Web site (http://www.rosacea.org) were conducted to identify articles and materials that quantitatively or qualitatively described rosacea patient experiences. Search terms included rosacea, rosacea patient experience, rosacea treatment, rosacea adherence, and rosacea quality of life. A Google search also was conducted using the same terms to obtain current news articles online. Current literature pertaining to the patient journey was summarized.

To create a model for the rosacea patient journey, we refined a rheumatoid arthritis patient journey map4 and included the critical components of the journey for rosacea patients. We organized the journey into stages, including prediagnosis, diagnosis, treatment, adherence, and management. We first explored what occurs prior to diagnosis, which includes the patient’s symptoms before visiting a physician. We then examined the process of diagnosis and the implementation of a treatment plan. Treatment adherence was then explored, ending with the ways patients self-manage their disease beyond the physician’s office.

Prediagnosis: What Motivates Patients to Seek Treatment

Rosacea can present with many symptoms that may lead patients to see a physician, including facial erythema and telangiectases, papules and pustules, phymatous changes, and ocular manifestations.5 The most common concern is temporary facial flushing, followed by persistent redness, then bumps and pimples.6 Many patients seek treatment after persistent facial flushing and an intolerable burning sensation. Some middle-aged patients decide to see a dermatologist for the first time when they break out in acne lesions after a history of clear skin. Others seek treatment because they can no longer tolerate the pain and embarrassment associated with their symptoms. However, patients who seek treatment only account for a small proportion of patients with rosacea, as only 10% of patients seek conventional medical treatment.7 Furthermore, symptomatic patients on average wait 7 months to 5 years before receiving a diagnosis.8,9

Care often is delayed or not pursued because many rosacea symptoms are mild when they first appear and may not initially bother the patient. Patients may not think anything of their symptoms and dismiss them as either acne vulgaris or sunburn. Due to the relapsing and remitting nature of the disease course, patients may feel their symptoms will resolve. Of patients diagnosed with rosacea, only one-half have heard of the condition prior to diagnosis,8 which can largely be attributed to lack of patient education on the signs and symptoms of rosacea, a concern that prompted the National Rosacea Society to designate the month of April as rosacea awareness month.5

With sales of antiredness facial care products growing 35% from 2002 to 2007, accounting for an increase of $300 million in revenue, patients also may be turning to over-the-counter products first.10 Men with rosacea tend to present with more severe symptoms such as rhinophyma, which may be due to their desire to wait until their symptoms reached more advanced stages of disease before seeking medical help.5

Diagnosis of Rosacea

After the patient decides that his/her symptoms are unusual, severe, or intolerable enough to seek treatment, the issues of access to dermatologic care and receiving the correct diagnosis come into play. Accessing dermatologic care can be difficult, as appointments may be hard to obtain, and even if the patient is able to get an appointment, it could be many weeks later.11 For some rosacea patients, the anxiety of waiting for their appointment prompts them to seek support and advice from online message boards (eg, http://www.rosacea-support.org). The long wait for appointments may be attributed to the increased demand for dermatologists for cosmetic procedures.12 Additionally, disparities according to insurance type can contribute to difficulties procuring an appointment. In one study, privately insured dermatology patients demonstrated a 91% acceptance rate and shorter wait times for appointments compared to publicly insured patients who were limited to a 29.8% acceptance rate and longer wait times.11 Many patients then are left to wait for an appointment with a dermatologist or instead turn to a primary care physician. Of patients diagnosed with rosacea in one study (N=2847), the majority of patients were seen by a dermatologist (79%), while the other patients were diagnosed by a family physician (14%) or other types of physicians such as internists and ophthalmologists (7%).6

The diagnosis of rosacea usually is not a major hurdle for dermatologists, but misdiagnoses can sometimes occur. The Rosacea Research & Development Institute compiled multiple patient anecdotes describing the struggles of finally reaching the correct diagnosis of rosacea; however, no estimates as to the frequency of misdiagnoses was estimated.13 Even with an accurate diagnosis of rosacea, correct classification of the 4 types of rosacea (ie, erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, ocular) is necessary to avoid incorrect treatment recommendations. For example, patients with flushing often cannot tolerate topical medications in contrast to patients with the papulopustular subtype who benefit from them.14 In the meantime, the patients who are misdiagnosed may be met with frustration, as treatment was either delayed or incorrectly prescribed.

Although there are limited data regarding patient reactions after receiving a diagnosis of rosacea, it can be assumed that patients would be hopeful that diagnosis would lead to correct treatment. In a 2008 article in The New York Times, a rosacea patient was described as feeling relieved to be diagnosed with rosacea because it was an explanation for the development of pimples on the cheeks in her late 40s.10

Implementation of a Treatment Plan

After recognizing the symptoms and receiving a correct diagnosis, the next step in the patient journey is treatment. Long-term management of incurable conditions such as rosacea is difficult. The main goals of treatment are to relieve symptoms, improve appearance, delay progression to advanced stages, and maintain remission.15 There are only a few reliable clinical trials regarding therapies for rosacea, so treatment has mostly relied on clinical experience (Table). The efficacy and safety of many older treatments has not been assessed.15 Mainstays of treatment include both topical agents and oral medications. The use of topical metronidazole, oral tetracycline, and oral isotretinoin have been found to improve both skin lesions and quality of life.18 Initially, a combination of a topical and an oral medication may be used for at least the first 12 weeks, and improvement is usually gradual, taking many weeks to become evident.15 Long-term treatment with topical medications often is required for maintenance, which can last another 6 months or more.19,20

Besides using pharmacologic therapies, some patients also may choose to undergo various procedures. The most common procedure is laser therapy, followed by dermabrasion, chemical peels, hot loop electrocoagulation, and surgical sculpting or plastic surgery.6 The use of these adjunct therapies may suggest impatience from the patient for improvement; it also indicates the lengths patients will go to and willingness to pay for improvement of symptoms.

Along with medication, patients are recommended to make changes to their skin care regimen and lifestyle. Rosacea patients typically have sensitive skin that may include symptoms such as dryness, scaling, stinging, burning, and pruritus.16 Skin care recommendations for rosacea patients include using a gentle cleanser and regularly applying sunscreen.5 Issues with physical appearance can be addressed with the use of cosmetic products such as green-tinted makeup to conceal skin lesions.21 Remission can be maintained by identifying certain triggers (eg, red wine, spicy foods, extreme temperatures, prolonged sun exposure, vigorous exercise) that can cause flare-ups.15 The most common trigger is sun exposure, making photoprotection an important component of the rosacea patient’s skin care regimen.6

Adherence

With a diagnosis and treatment plan in effect, the patient journey reaches the stage of treatment adherence, which should include ongoing education about the condition. Self-reported statistics from rosacea patients indicated that 28% of patients took time off from their treatment regimen,6 but actual nonadherence rates likely are higher. The most commonly reported reason for poor treatment adherence among rosacea patients was the impression that the symptoms had resolved or were adequately controlled.6 Treatment also must be affordable. In a national survey of rosacea patients, 24% of 427 patients receiving pharmacologic therapy planned on switching medications because of cost, and 17% of 769 patients discontinued medications due to co-pay/insurance issues.6 Other reasons cited for discontinuation of treatment included patient perception that symptoms were not that serious, co-pay/insurance issues, ineffectiveness of the medication, and side effects.6 Adherence to topical medications is lower than oral medications due to the time and inconvenience required for application.22 For some patients, topical medications may be too messy, have a strange odor, or stain clothing.

It is promising that most rosacea patients have reported the intent to continue using pharmacologic agents because the medication prevented worsening of their symptoms.6 However, there are still patients who switch or discontinue therapies without physician direction. These patients often cite that they desire more information at the time of diagnosis, particularly related to causes of flare-ups, physical symptoms to expect, drug treatment options, makeup to cover up visible symptoms, surgical or laser treatment options, psychological symptoms, patient support groups, and counseling options.6

Management

The last part of the journey is disease management, which occurs when the patient learns how to control his/her symptoms long-term. Important factors contributing to long-term control of rosacea flares are medication adherence and avoiding lifestyle triggers.23,24 Through the other stages of the journey, the patient has learned which treatments work and which factors may lead to exacerbation of symptoms.

Educating Patients on the Journey

The patient journey is a concept that can be applied to any disease state and brings to light roadblocks that patients may face from the initial diagnosis to successful disease management. Rosacea patients are faced with confusing and aggravating symptoms that can cause anxiety and may lead them to seek treatment from a physician. Facial flushing and phymatous changes of the nose can be mistaken for alcohol abuse, leading rosacea to be a socially stigmatizing disease.15 Because rosacea involves mostly the facial skin, it can disrupt social and professional interactions, leading to quality-of-life effects such as difficulty functioning on a day-to-day basis, which can be detrimental because patients usually are aged 30 to 50 years and may be perceived based on their appearance in the workforce.3 A lack of confidence, low self-esteem, embarrassment, and anxiety can even lead to serious psychiatric conditions such as depression and body dysmorphic disorder.25 Because the severity of rosacea increases over time, it is important to educate patients about seeking early treatment; therefore, understanding and awareness of rosacea symptoms are necessary to prompt patients to see a medical professional to either confirm or refute the diagnosis.

Rosacea is a clinical diagnosis that relies on patterns of primary and secondary features, as outlined in a 2002 report by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea.5 Even with this consensus grading system, it appears that additional fine-tuning of the criteria is needed in the disease definition. Importantly, because much of the pathogenesis and progression of rosacea is still not completely understood, there is no laboratory benchmark test that can be utilized for correct diagnosis.14 Moreover, many of the clinical manifestations of rosacea are shared with other conditions, and patients may present with different symptoms or varying combinations.26

Treatment of rosacea is multifactorial and behavioral, as patients must not only be able to obtain and adhere to oral and topical regimens and possible procedures but also avoid various lifestyle and environmental triggers and learn to cope with emotional distress caused by their symptoms. Although patients who discontinue use of medications appear to be in the minority, education is still needed to stress the chronic nature of rosacea and the importance of the continuation of treatment. Collaboration between the physician and patient is needed to determine why a certain medication may not be effective and explore other treatment options. Treatment ineffectiveness could be due to incorrect use of the product, failure to use an adjunct skin care regimen, or inability to control rosacea triggers. Adequate early follow-up also is needed to maximize patient adherence to treatment.27 Working together with the patient to develop a treatment plan that can be followed is necessary for long-term control of rosacea symptoms.

There is little information on how to address the psychological needs of patients, but patients can find support from various avenues. For instance, the National Rosacea Society, a large advocacy group, produces newsletters and educational materials for both physicians and patients.28,29 There also are online support groups for rosacea patients that have thousands of members who exchange stories and provide words of encouragement. Although there are not many face-to-face support groups, physicians may consider developing live support groups for their rosacea patients. As patients achieve the later stages of the rosacea patient journey, they hopefully will have controlled their symptoms by following a treatment regimen and learning to adapt to a new life of successful disease management.

Many aspects of the rosacea patient journey have yet to be explored. It is uncertain how long patients with symptoms of rosacea wait before seeking treatment, what methods they use to control their rosacea before they receive a prescribed treatment or physician recommendations, and how they react to their diagnosis. It also is unknown how many rosacea patients receive an initial misdiagnosis of another condition and which physicians typically make the misdiagnosis. We also need to know more about the role of psychological issues in addressing patient adherence to treatment. Similarly, what role do support groups such as online forums play on adherence? There is a need for more patient education and awareness of rosacea.

Conclusion

Patients may be relieved that rosacea is not a life-threatening condition, but they may be disappointed that there is no cure for rosacea. As the patient and dermatologist work together to find an appropriate treatment plan, identify certain triggers, and modify the skin care routine, the patient can become disciplined in controlling rosacea symptoms. Ultimately, with the alleviation of visible symptoms, the patient’s quality of life also can improve. Better understanding of the rosacea patient perspective can lead to a more efficient health care system, improved patient care, and better patient satisfaction.

Rosacea patients experience symptoms ranging from flushing to persistent acnelike rashes that can cause low self-esteem and anxiety, leading to social and professional isolation.1 Although it is estimated that 16 million individuals in the United States have rosacea, only 10% seek treatment.2,3 The motivation for patients to seek and adhere to treatment is not well characterized.

A patient journey is a map of the steps a patient takes as he/she progresses through different segments of the disease from diagnosis to management, including all the influences that can push him/her toward or away from certain decisions. The patient journey model provides a structure for understanding key issues in rosacea management, including barriers to successful treatment outcomes.

The patient journey model progresses from development of disease and diagnosis to treatment and disease management (Figure). We sought to examine each step of the rosacea patient journey to better understand key patient care boundaries faced by rosacea patients. We assessed the current literature regarding each step of the patient experience and identified areas of the patient journey with limited research.

Click here to view the figure as a PDF to print for future reference.

Researching the Patient Experience

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a search of the National Rosacea Society Web site (http://www.rosacea.org) were conducted to identify articles and materials that quantitatively or qualitatively described rosacea patient experiences. Search terms included rosacea, rosacea patient experience, rosacea treatment, rosacea adherence, and rosacea quality of life. A Google search also was conducted using the same terms to obtain current news articles online. Current literature pertaining to the patient journey was summarized.

To create a model for the rosacea patient journey, we refined a rheumatoid arthritis patient journey map4 and included the critical components of the journey for rosacea patients. We organized the journey into stages, including prediagnosis, diagnosis, treatment, adherence, and management. We first explored what occurs prior to diagnosis, which includes the patient’s symptoms before visiting a physician. We then examined the process of diagnosis and the implementation of a treatment plan. Treatment adherence was then explored, ending with the ways patients self-manage their disease beyond the physician’s office.

Prediagnosis: What Motivates Patients to Seek Treatment

Rosacea can present with many symptoms that may lead patients to see a physician, including facial erythema and telangiectases, papules and pustules, phymatous changes, and ocular manifestations.5 The most common concern is temporary facial flushing, followed by persistent redness, then bumps and pimples.6 Many patients seek treatment after persistent facial flushing and an intolerable burning sensation. Some middle-aged patients decide to see a dermatologist for the first time when they break out in acne lesions after a history of clear skin. Others seek treatment because they can no longer tolerate the pain and embarrassment associated with their symptoms. However, patients who seek treatment only account for a small proportion of patients with rosacea, as only 10% of patients seek conventional medical treatment.7 Furthermore, symptomatic patients on average wait 7 months to 5 years before receiving a diagnosis.8,9

Care often is delayed or not pursued because many rosacea symptoms are mild when they first appear and may not initially bother the patient. Patients may not think anything of their symptoms and dismiss them as either acne vulgaris or sunburn. Due to the relapsing and remitting nature of the disease course, patients may feel their symptoms will resolve. Of patients diagnosed with rosacea, only one-half have heard of the condition prior to diagnosis,8 which can largely be attributed to lack of patient education on the signs and symptoms of rosacea, a concern that prompted the National Rosacea Society to designate the month of April as rosacea awareness month.5

With sales of antiredness facial care products growing 35% from 2002 to 2007, accounting for an increase of $300 million in revenue, patients also may be turning to over-the-counter products first.10 Men with rosacea tend to present with more severe symptoms such as rhinophyma, which may be due to their desire to wait until their symptoms reached more advanced stages of disease before seeking medical help.5

Diagnosis of Rosacea

After the patient decides that his/her symptoms are unusual, severe, or intolerable enough to seek treatment, the issues of access to dermatologic care and receiving the correct diagnosis come into play. Accessing dermatologic care can be difficult, as appointments may be hard to obtain, and even if the patient is able to get an appointment, it could be many weeks later.11 For some rosacea patients, the anxiety of waiting for their appointment prompts them to seek support and advice from online message boards (eg, http://www.rosacea-support.org). The long wait for appointments may be attributed to the increased demand for dermatologists for cosmetic procedures.12 Additionally, disparities according to insurance type can contribute to difficulties procuring an appointment. In one study, privately insured dermatology patients demonstrated a 91% acceptance rate and shorter wait times for appointments compared to publicly insured patients who were limited to a 29.8% acceptance rate and longer wait times.11 Many patients then are left to wait for an appointment with a dermatologist or instead turn to a primary care physician. Of patients diagnosed with rosacea in one study (N=2847), the majority of patients were seen by a dermatologist (79%), while the other patients were diagnosed by a family physician (14%) or other types of physicians such as internists and ophthalmologists (7%).6

The diagnosis of rosacea usually is not a major hurdle for dermatologists, but misdiagnoses can sometimes occur. The Rosacea Research & Development Institute compiled multiple patient anecdotes describing the struggles of finally reaching the correct diagnosis of rosacea; however, no estimates as to the frequency of misdiagnoses was estimated.13 Even with an accurate diagnosis of rosacea, correct classification of the 4 types of rosacea (ie, erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, ocular) is necessary to avoid incorrect treatment recommendations. For example, patients with flushing often cannot tolerate topical medications in contrast to patients with the papulopustular subtype who benefit from them.14 In the meantime, the patients who are misdiagnosed may be met with frustration, as treatment was either delayed or incorrectly prescribed.

Although there are limited data regarding patient reactions after receiving a diagnosis of rosacea, it can be assumed that patients would be hopeful that diagnosis would lead to correct treatment. In a 2008 article in The New York Times, a rosacea patient was described as feeling relieved to be diagnosed with rosacea because it was an explanation for the development of pimples on the cheeks in her late 40s.10

Implementation of a Treatment Plan

After recognizing the symptoms and receiving a correct diagnosis, the next step in the patient journey is treatment. Long-term management of incurable conditions such as rosacea is difficult. The main goals of treatment are to relieve symptoms, improve appearance, delay progression to advanced stages, and maintain remission.15 There are only a few reliable clinical trials regarding therapies for rosacea, so treatment has mostly relied on clinical experience (Table). The efficacy and safety of many older treatments has not been assessed.15 Mainstays of treatment include both topical agents and oral medications. The use of topical metronidazole, oral tetracycline, and oral isotretinoin have been found to improve both skin lesions and quality of life.18 Initially, a combination of a topical and an oral medication may be used for at least the first 12 weeks, and improvement is usually gradual, taking many weeks to become evident.15 Long-term treatment with topical medications often is required for maintenance, which can last another 6 months or more.19,20

Besides using pharmacologic therapies, some patients also may choose to undergo various procedures. The most common procedure is laser therapy, followed by dermabrasion, chemical peels, hot loop electrocoagulation, and surgical sculpting or plastic surgery.6 The use of these adjunct therapies may suggest impatience from the patient for improvement; it also indicates the lengths patients will go to and willingness to pay for improvement of symptoms.

Along with medication, patients are recommended to make changes to their skin care regimen and lifestyle. Rosacea patients typically have sensitive skin that may include symptoms such as dryness, scaling, stinging, burning, and pruritus.16 Skin care recommendations for rosacea patients include using a gentle cleanser and regularly applying sunscreen.5 Issues with physical appearance can be addressed with the use of cosmetic products such as green-tinted makeup to conceal skin lesions.21 Remission can be maintained by identifying certain triggers (eg, red wine, spicy foods, extreme temperatures, prolonged sun exposure, vigorous exercise) that can cause flare-ups.15 The most common trigger is sun exposure, making photoprotection an important component of the rosacea patient’s skin care regimen.6

Adherence

With a diagnosis and treatment plan in effect, the patient journey reaches the stage of treatment adherence, which should include ongoing education about the condition. Self-reported statistics from rosacea patients indicated that 28% of patients took time off from their treatment regimen,6 but actual nonadherence rates likely are higher. The most commonly reported reason for poor treatment adherence among rosacea patients was the impression that the symptoms had resolved or were adequately controlled.6 Treatment also must be affordable. In a national survey of rosacea patients, 24% of 427 patients receiving pharmacologic therapy planned on switching medications because of cost, and 17% of 769 patients discontinued medications due to co-pay/insurance issues.6 Other reasons cited for discontinuation of treatment included patient perception that symptoms were not that serious, co-pay/insurance issues, ineffectiveness of the medication, and side effects.6 Adherence to topical medications is lower than oral medications due to the time and inconvenience required for application.22 For some patients, topical medications may be too messy, have a strange odor, or stain clothing.

It is promising that most rosacea patients have reported the intent to continue using pharmacologic agents because the medication prevented worsening of their symptoms.6 However, there are still patients who switch or discontinue therapies without physician direction. These patients often cite that they desire more information at the time of diagnosis, particularly related to causes of flare-ups, physical symptoms to expect, drug treatment options, makeup to cover up visible symptoms, surgical or laser treatment options, psychological symptoms, patient support groups, and counseling options.6

Management

The last part of the journey is disease management, which occurs when the patient learns how to control his/her symptoms long-term. Important factors contributing to long-term control of rosacea flares are medication adherence and avoiding lifestyle triggers.23,24 Through the other stages of the journey, the patient has learned which treatments work and which factors may lead to exacerbation of symptoms.

Educating Patients on the Journey

The patient journey is a concept that can be applied to any disease state and brings to light roadblocks that patients may face from the initial diagnosis to successful disease management. Rosacea patients are faced with confusing and aggravating symptoms that can cause anxiety and may lead them to seek treatment from a physician. Facial flushing and phymatous changes of the nose can be mistaken for alcohol abuse, leading rosacea to be a socially stigmatizing disease.15 Because rosacea involves mostly the facial skin, it can disrupt social and professional interactions, leading to quality-of-life effects such as difficulty functioning on a day-to-day basis, which can be detrimental because patients usually are aged 30 to 50 years and may be perceived based on their appearance in the workforce.3 A lack of confidence, low self-esteem, embarrassment, and anxiety can even lead to serious psychiatric conditions such as depression and body dysmorphic disorder.25 Because the severity of rosacea increases over time, it is important to educate patients about seeking early treatment; therefore, understanding and awareness of rosacea symptoms are necessary to prompt patients to see a medical professional to either confirm or refute the diagnosis.

Rosacea is a clinical diagnosis that relies on patterns of primary and secondary features, as outlined in a 2002 report by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea.5 Even with this consensus grading system, it appears that additional fine-tuning of the criteria is needed in the disease definition. Importantly, because much of the pathogenesis and progression of rosacea is still not completely understood, there is no laboratory benchmark test that can be utilized for correct diagnosis.14 Moreover, many of the clinical manifestations of rosacea are shared with other conditions, and patients may present with different symptoms or varying combinations.26

Treatment of rosacea is multifactorial and behavioral, as patients must not only be able to obtain and adhere to oral and topical regimens and possible procedures but also avoid various lifestyle and environmental triggers and learn to cope with emotional distress caused by their symptoms. Although patients who discontinue use of medications appear to be in the minority, education is still needed to stress the chronic nature of rosacea and the importance of the continuation of treatment. Collaboration between the physician and patient is needed to determine why a certain medication may not be effective and explore other treatment options. Treatment ineffectiveness could be due to incorrect use of the product, failure to use an adjunct skin care regimen, or inability to control rosacea triggers. Adequate early follow-up also is needed to maximize patient adherence to treatment.27 Working together with the patient to develop a treatment plan that can be followed is necessary for long-term control of rosacea symptoms.

There is little information on how to address the psychological needs of patients, but patients can find support from various avenues. For instance, the National Rosacea Society, a large advocacy group, produces newsletters and educational materials for both physicians and patients.28,29 There also are online support groups for rosacea patients that have thousands of members who exchange stories and provide words of encouragement. Although there are not many face-to-face support groups, physicians may consider developing live support groups for their rosacea patients. As patients achieve the later stages of the rosacea patient journey, they hopefully will have controlled their symptoms by following a treatment regimen and learning to adapt to a new life of successful disease management.

Many aspects of the rosacea patient journey have yet to be explored. It is uncertain how long patients with symptoms of rosacea wait before seeking treatment, what methods they use to control their rosacea before they receive a prescribed treatment or physician recommendations, and how they react to their diagnosis. It also is unknown how many rosacea patients receive an initial misdiagnosis of another condition and which physicians typically make the misdiagnosis. We also need to know more about the role of psychological issues in addressing patient adherence to treatment. Similarly, what role do support groups such as online forums play on adherence? There is a need for more patient education and awareness of rosacea.

Conclusion

Patients may be relieved that rosacea is not a life-threatening condition, but they may be disappointed that there is no cure for rosacea. As the patient and dermatologist work together to find an appropriate treatment plan, identify certain triggers, and modify the skin care routine, the patient can become disciplined in controlling rosacea symptoms. Ultimately, with the alleviation of visible symptoms, the patient’s quality of life also can improve. Better understanding of the rosacea patient perspective can lead to a more efficient health care system, improved patient care, and better patient satisfaction.

1. Baldwin HE. Systemic therapy for rosacea. Skin Therapy Lett. 2007;12:1-5, 9.

2. Drake L. Rosacea now estimated to affect at least 16 million Americans. Rosacea Review. Winter 2010. http://www.rosacea.org/rr/2010/winter/article_1.php. Accessed December 11, 2014.

3. Rosacea as an inflammatory disease: an expert interview with Brian Berman, MD, PhD. Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/722156. Published May 27, 2010. Accessed December 11, 2014.

4. HealthEd Group, Inc. Rheumatoid arthritis patient journey map. http://visual.ly/rheumatoid-arthritis-patient-journey-map. Accessed December 19, 2014.

5. Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

6. Elewski BE. Results of a national rosacea patient survey: common issues that concern rosacea sufferers. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:120-123.

7. Del Rosso J. Management of rosacea in the United States: analysis based on recent prescribing patterns and insurance claims. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:AB13.

8. New survey reveals first impressions may not always be rosy for people with the widespread skin condition rosacea. Medical News Today Web site. http://www.medicalnew today.com/releases/185491.php. Updated April 15, 2010. Accessed December 12, 2014.

9. Shear NH, Levine C. Needs survey of Canadian rosacea patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:178-181.

10. Sweeney C. In a perfect world, rosacea remains a problem. New York Times. April 24, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/24/fashion/24SKIN.html?pagewanted=all. Accessed December 12, 2014.

11. Alghothani L, Jacks SK, Vander HA, et al. Disparities in access to dermatologic care according to insurance type. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:956-957.

12. Resneck J Jr. Too few or too many dermatologists? difficulties in assessing optimal workforce size. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1295-1301.

13. Rosacea Research & Development Institute Web site. http://irosacea.org/misdiagnosed_rosacea.html. Accessed December 19, 2014.

14. Crawford GH, Pelle MT, James WD. Rosacea: I. etiology, pathogenesis, and subtype classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:327-341.

15. Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dreno B, et al. Rosacea—global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:188-200.

16. Del Rosso JQ, Baldwin H, Webster G. American Acne & Rosacea Society rosacea medical management guidelines. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:531-533.

17. Fowler J Jr, Jackson M, Moore A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, and vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:650-656.

18. Aksoy B, Altaykan-Hapa A, Egemen D, et al. The impact of rosacea on quality of life: effects of demographic and clinical characteristics and various treatment modalities. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:719-725.

19. Dahl MV, Katz HI, Krueger GG, et al. Topical metronidazole maintains remissions of rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:679-683.

20. Thiboutot DM, Fleischer AB, Del Rosso JQ, et al. A multicenter study of topical azelaic acid 15% gel in combination with oral doxycycline as initial therapy and azelaic acid 15% gel as maintenance monotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:639-648.

21. Boehncke WH, Ochsendorf F, Paeslack I, et al. Decorative cosmetics improve the quality of life in patients with disfiguring skin diseases. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:577-580.

22. Jackson JM, Pelle M. Topical rosacea therapy: the importance of vehicles for efficacy, tolerability and compliance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:627-633.

23. Wolf JE Jr. Medication adherence: a key factor in effective management of rosacea. Adv Ther. 2001;18:272-281.

24. Managing rosacea. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/patients/materials/managing/lifestyle.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

25. van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Lack of ‘appropriately assessed’ patient-reported outcomes in randomized controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of interventions for rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:442-444.

26. Del Rosso JQ. Advances in understanding and managing rosacea: part 2: the central role, evaluation, and medical management of diffuse and persistent facial erythema of rosacea. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:26-36.

27. Davis SA, Lin HC, Yu CH, et al. Underuse of early follow-up visits: a missed opportunity to improve patients’ adherence. 2014;13:833-836.

28. If you have rosacea, you’re not alone. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/patients/index.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

29. Tools for the professional. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/physicians/index.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

1. Baldwin HE. Systemic therapy for rosacea. Skin Therapy Lett. 2007;12:1-5, 9.

2. Drake L. Rosacea now estimated to affect at least 16 million Americans. Rosacea Review. Winter 2010. http://www.rosacea.org/rr/2010/winter/article_1.php. Accessed December 11, 2014.

3. Rosacea as an inflammatory disease: an expert interview with Brian Berman, MD, PhD. Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/722156. Published May 27, 2010. Accessed December 11, 2014.

4. HealthEd Group, Inc. Rheumatoid arthritis patient journey map. http://visual.ly/rheumatoid-arthritis-patient-journey-map. Accessed December 19, 2014.

5. Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

6. Elewski BE. Results of a national rosacea patient survey: common issues that concern rosacea sufferers. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:120-123.

7. Del Rosso J. Management of rosacea in the United States: analysis based on recent prescribing patterns and insurance claims. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:AB13.

8. New survey reveals first impressions may not always be rosy for people with the widespread skin condition rosacea. Medical News Today Web site. http://www.medicalnew today.com/releases/185491.php. Updated April 15, 2010. Accessed December 12, 2014.

9. Shear NH, Levine C. Needs survey of Canadian rosacea patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:178-181.

10. Sweeney C. In a perfect world, rosacea remains a problem. New York Times. April 24, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/24/fashion/24SKIN.html?pagewanted=all. Accessed December 12, 2014.

11. Alghothani L, Jacks SK, Vander HA, et al. Disparities in access to dermatologic care according to insurance type. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:956-957.

12. Resneck J Jr. Too few or too many dermatologists? difficulties in assessing optimal workforce size. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1295-1301.

13. Rosacea Research & Development Institute Web site. http://irosacea.org/misdiagnosed_rosacea.html. Accessed December 19, 2014.

14. Crawford GH, Pelle MT, James WD. Rosacea: I. etiology, pathogenesis, and subtype classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:327-341.

15. Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dreno B, et al. Rosacea—global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:188-200.

16. Del Rosso JQ, Baldwin H, Webster G. American Acne & Rosacea Society rosacea medical management guidelines. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:531-533.

17. Fowler J Jr, Jackson M, Moore A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, and vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:650-656.

18. Aksoy B, Altaykan-Hapa A, Egemen D, et al. The impact of rosacea on quality of life: effects of demographic and clinical characteristics and various treatment modalities. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:719-725.

19. Dahl MV, Katz HI, Krueger GG, et al. Topical metronidazole maintains remissions of rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:679-683.

20. Thiboutot DM, Fleischer AB, Del Rosso JQ, et al. A multicenter study of topical azelaic acid 15% gel in combination with oral doxycycline as initial therapy and azelaic acid 15% gel as maintenance monotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:639-648.

21. Boehncke WH, Ochsendorf F, Paeslack I, et al. Decorative cosmetics improve the quality of life in patients with disfiguring skin diseases. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:577-580.

22. Jackson JM, Pelle M. Topical rosacea therapy: the importance of vehicles for efficacy, tolerability and compliance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:627-633.

23. Wolf JE Jr. Medication adherence: a key factor in effective management of rosacea. Adv Ther. 2001;18:272-281.

24. Managing rosacea. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/patients/materials/managing/lifestyle.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

25. van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Lack of ‘appropriately assessed’ patient-reported outcomes in randomized controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of interventions for rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:442-444.

26. Del Rosso JQ. Advances in understanding and managing rosacea: part 2: the central role, evaluation, and medical management of diffuse and persistent facial erythema of rosacea. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:26-36.

27. Davis SA, Lin HC, Yu CH, et al. Underuse of early follow-up visits: a missed opportunity to improve patients’ adherence. 2014;13:833-836.

28. If you have rosacea, you’re not alone. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/patients/index.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

29. Tools for the professional. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/physicians/index.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

Practice Points

- For patients who are emotionally distressed by their rosacea and who lack a social support network, several rosacea-focused online support systems are available.

- An early follow-up visit to evaluate newly prescribed treatments can positively influence disease management.

Photosensitivity Reaction From Dronedarone for Atrial Fibrillation

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia presented with an erythematous, edematous, pruritic eruption on the chest, neck, and arms of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had no history of considerable sun exposure or reports of photosensitivity. One month prior to presentation she had started taking dronedarone for improved control of atrial fibrillation. She had no known history of drug allergies. Other medications included valsartan, digoxin, pioglitazone, simvastatin, aspirin, hydrocodone, and zolpidem, all of which were unchanged for years. There were no changes in topical products used.

Physical examination revealed confluent, well-demarcated, erythematous and edematous papules and plaques over the anterior aspect of the neck, bilateral forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands, with a v-shaped distribution on the chest (Figure). There was notable sparing of the submental region, upper arms, abdomen, back, and legs. Dronedarone was discontinued and she was started on fluocinonide ointment 0.05% and oral hydroxyzine for pruritus. Her rash resolved within the following few weeks.

|

|

| Confluent, well-demarcated, erythematous and edematous papules and plaques in a v-shaped distribution on the chest (A) and dorsal aspect of the hands (B). |

Dronedarone is a noniodinated benzofuran derivative. It is structurally similar to and shares the antiarrhythmic properties of amiodarone,1 and thus it is used in the treatment of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. However, the pulmonary and thyroid toxicities sometimes associated with amiodarone have not been observed with dronedarone. The primary side effect of dronedarone is gastrointestinal distress, specifically nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Dronedarone has been associated with severe liver injury and hepatic failure.2 Cutaneous reactions appear to be an uncommon side effect of dronedarone therapy. Across 5 clinical studies (N=6285), adverse events involving skin and subcutaneous tissue including eczema, allergic dermatitis, pruritus, and nonspecific rash occurred in 5% of dronedarone and 3% of placebo patients. Photosensitivity reactions occurred in less than 1% of dronedarone recipients.3

Although the lack of a biopsy leaves the possibility of a contact or photocontact dermatitis, our patient demonstrated the potential for dronedarone to cause a photodistributed drug eruption that resolved after cessation of the medication.

1. Hoy SM, Keam SJ. Dronedarone. Drugs. 2009;69:1647-1663.

2. In brief: FDA warning on dronedarone (Multaq). Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2011;53:17.

3. Multaq [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis; 2009.

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia presented with an erythematous, edematous, pruritic eruption on the chest, neck, and arms of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had no history of considerable sun exposure or reports of photosensitivity. One month prior to presentation she had started taking dronedarone for improved control of atrial fibrillation. She had no known history of drug allergies. Other medications included valsartan, digoxin, pioglitazone, simvastatin, aspirin, hydrocodone, and zolpidem, all of which were unchanged for years. There were no changes in topical products used.

Physical examination revealed confluent, well-demarcated, erythematous and edematous papules and plaques over the anterior aspect of the neck, bilateral forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands, with a v-shaped distribution on the chest (Figure). There was notable sparing of the submental region, upper arms, abdomen, back, and legs. Dronedarone was discontinued and she was started on fluocinonide ointment 0.05% and oral hydroxyzine for pruritus. Her rash resolved within the following few weeks.

|

|

| Confluent, well-demarcated, erythematous and edematous papules and plaques in a v-shaped distribution on the chest (A) and dorsal aspect of the hands (B). |

Dronedarone is a noniodinated benzofuran derivative. It is structurally similar to and shares the antiarrhythmic properties of amiodarone,1 and thus it is used in the treatment of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. However, the pulmonary and thyroid toxicities sometimes associated with amiodarone have not been observed with dronedarone. The primary side effect of dronedarone is gastrointestinal distress, specifically nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Dronedarone has been associated with severe liver injury and hepatic failure.2 Cutaneous reactions appear to be an uncommon side effect of dronedarone therapy. Across 5 clinical studies (N=6285), adverse events involving skin and subcutaneous tissue including eczema, allergic dermatitis, pruritus, and nonspecific rash occurred in 5% of dronedarone and 3% of placebo patients. Photosensitivity reactions occurred in less than 1% of dronedarone recipients.3

Although the lack of a biopsy leaves the possibility of a contact or photocontact dermatitis, our patient demonstrated the potential for dronedarone to cause a photodistributed drug eruption that resolved after cessation of the medication.

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia presented with an erythematous, edematous, pruritic eruption on the chest, neck, and arms of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had no history of considerable sun exposure or reports of photosensitivity. One month prior to presentation she had started taking dronedarone for improved control of atrial fibrillation. She had no known history of drug allergies. Other medications included valsartan, digoxin, pioglitazone, simvastatin, aspirin, hydrocodone, and zolpidem, all of which were unchanged for years. There were no changes in topical products used.

Physical examination revealed confluent, well-demarcated, erythematous and edematous papules and plaques over the anterior aspect of the neck, bilateral forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands, with a v-shaped distribution on the chest (Figure). There was notable sparing of the submental region, upper arms, abdomen, back, and legs. Dronedarone was discontinued and she was started on fluocinonide ointment 0.05% and oral hydroxyzine for pruritus. Her rash resolved within the following few weeks.

|

|

| Confluent, well-demarcated, erythematous and edematous papules and plaques in a v-shaped distribution on the chest (A) and dorsal aspect of the hands (B). |

Dronedarone is a noniodinated benzofuran derivative. It is structurally similar to and shares the antiarrhythmic properties of amiodarone,1 and thus it is used in the treatment of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. However, the pulmonary and thyroid toxicities sometimes associated with amiodarone have not been observed with dronedarone. The primary side effect of dronedarone is gastrointestinal distress, specifically nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Dronedarone has been associated with severe liver injury and hepatic failure.2 Cutaneous reactions appear to be an uncommon side effect of dronedarone therapy. Across 5 clinical studies (N=6285), adverse events involving skin and subcutaneous tissue including eczema, allergic dermatitis, pruritus, and nonspecific rash occurred in 5% of dronedarone and 3% of placebo patients. Photosensitivity reactions occurred in less than 1% of dronedarone recipients.3

Although the lack of a biopsy leaves the possibility of a contact or photocontact dermatitis, our patient demonstrated the potential for dronedarone to cause a photodistributed drug eruption that resolved after cessation of the medication.

1. Hoy SM, Keam SJ. Dronedarone. Drugs. 2009;69:1647-1663.

2. In brief: FDA warning on dronedarone (Multaq). Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2011;53:17.

3. Multaq [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis; 2009.

1. Hoy SM, Keam SJ. Dronedarone. Drugs. 2009;69:1647-1663.

2. In brief: FDA warning on dronedarone (Multaq). Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2011;53:17.

3. Multaq [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis; 2009.