User login

Onychomycosis Treatment in the United States

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails caused by dermatophytes, nondermatophyte molds, and yeasts, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common causative organism.1-3 Onychomycosis affects approximately 2% to 26% of different populations worldwide. It represents 20% to 50% of onychopathies and approximately 30% of fungal cutaneous infections.4-9 Less than 30% of infected persons seek medical advice or treatment even in developed areas of the world.10 Onychomycosis may be a source of more widespread fungal skin infections or give rise to complications such as cellulitis. Chronic, long-lasting infection may result in nail dystrophy and can lead to pain, absence from work, and decreased quality of life.1,11 Because the dermatophyte can contaminate communal bathing facilities and spread to others,12 it is important to effectively target and treat patients with onychomycosis, thus reducing the rate of related morbidities.1,9

The primary aim of onychomycosis treatment is to cure the infection and prevent relapse. Both topical and oral agents are available for the treatment of fungal nail infections. Generally, systemic therapy for onychomycosis is more successful than topical treatment, likely due to poor penetration of topical medications into the nail plate.1,2,9 However, newer topical drugs have shown promising results in treating some types of onychomycosis.13 In its guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis, the British Association of Dermatologists recommends use of topical treatment under the following conditions: (1) when there is not extensive involvement of the nail plate (eg, candidal paronychia, superficial white onychomycosis, early stages of distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis), (2) when systemic therapy is contraindicated, or (3) in combination with systemic therapy.1 Although there are multiple treatments for fungal nail infections, there are limited reports on the ways in which physicians actually use these treatments or the frequency with which they prescribe them.

This study provides a representative portrayal of onychomycosis visits in the US outpatient setting using a large nationally sampled survey. In particular, we aimed to assess the number of visits related to onychomycosis, the demographics of patients, and the treatments being prescribed for onychomycosis.

Methods

Study Design

Data from January 1, 1993, to December 31, 2010, were collected from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), an ongoing survey of nonfederal employed US office-based physicians who are primarily engaged in direct patient care. The NAMCS has been conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics every year since 1989 to estimate the utilization of ambulatory care services in the United States. Since 1989 including 1993 to 2010, the NAMCS sampled approximately 30,000 visits per year. For each visit sampled, a 1-page patient log including demographic data, physicians’ diagnoses, services provided, and medications was completed. In the NAMCS survey, visits were divided into 2 groups: (1) visits from established patients that have been seen in that office before for any reason, and (2) visits for new (ie, first-time) patients. The current study included all visits in which fungal nail infection (code 110.1 according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]) was listed as 1 of 3 possible diagnoses.

Statistical Analysis

Sampling weights were applied to data to produce estimates for the total US outpatient setting.14 Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2, and SAS survey analysis procedures were used to account for the clustered sampling of the survey. The total numbers of visits for which onychomycosis was 1 of 3 possible diagnoses and for which it was the sole diagnosis were reported. Visit rates per population by demographic characteristics (ie, patient sex, age, race, and ethnicity) were calculated. Population estimates were based on the 2001 NAMCS Public Micro-Data File Documentation records of the US census estimates for noninstitutionalized civilian persons.15 Trends in proportion of visits linked with an onychomycosis diagnosis over time were evaluated using the SAS SURVEYREG procedure. Types of physicians who attended to these visits as well as leading comorbidities that had been diagnosed and documented in the medical record were characterized. Onychomycosis-related medications prescribed at these visits were reported and prescribing trends over time were evaluated. Differences in the treatment prescribed according to the type of visit (ie, first-time or return visit); physician specialty; and patients’ gender, race, and health conditions (eg, obesity, diabetes mellitus) were examined. To exclude the possibility that fluconazole and other broad-spectrum antifungals were being used for secondary diagnoses, we determined the number of visits that had an additional diagnosis of either candidiasis (ICD-9 codes 112.0–112.9) or “other specified erythematous conditions” (ICD-9 code 695.89).

Results

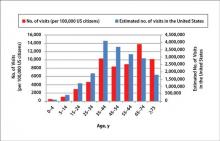

During the 18-year study period, 636 visits with a diagnosis of onychomycosis were recorded in the NAMCS database. This unweighted number of visits corresponded with approximately 19,350,000 visits (an average of 1,075,000 visits per year) to physicians’ offices with a diagnosis of onychomycosis in the United States during this period. Among these visits, there were an estimated 4,250,000 visits with fungal nail infection as the only diagnosis (no other comorbidities recorded). The recorded visits included more female (57.6%) than male (42.4%) patients, and 85% of patients were white (Table). Patients aged 35 to 44 years accounted for the largest number of visits; however, the estimated rate of onychomycosis visits per 100,000 US citizens was highest among those aged 65 to 74 years (Figure 1).

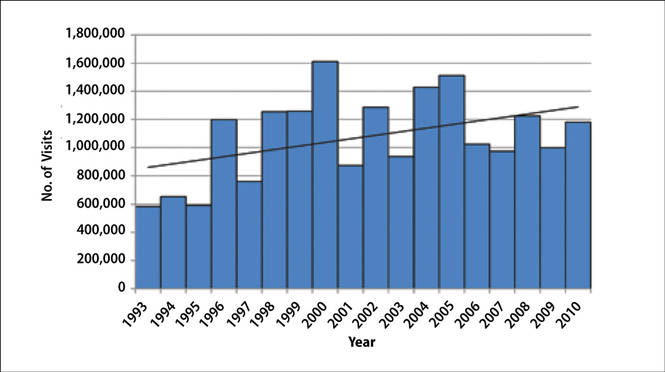

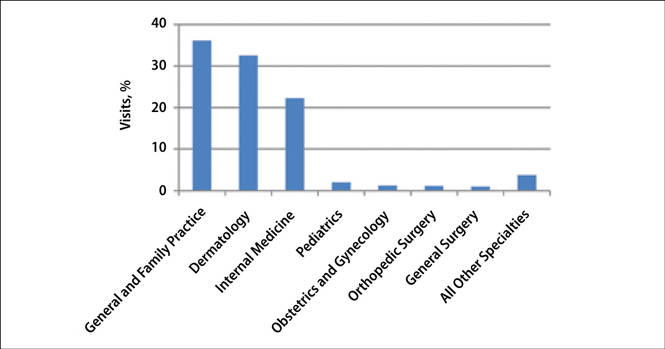

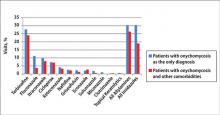

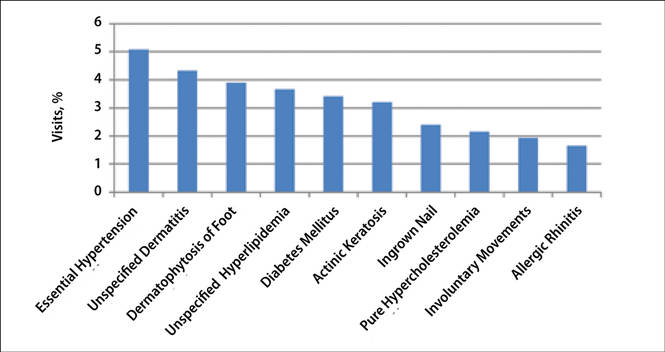

The number of US outpatient visits with a recorded diagnosis of onychomycosis increased from 1993 to 2010 (Figure 2); however, there was no change in the ratio of onychomycosis visits to the total number of recorded visits in NAMCS database during the study period (P=.9). A combined total of 91% of onychomycosis visits were to general and family practitioners, dermatologists, or internal medicine practitioners (Figure 3). Although cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus accounted for a large proportion of comorbidities, conditions affecting the feet (eg, tinea pedis, ingrown nails) also were among the most common comorbidities (Figure 4).

|

In both topical and systemic form, terbinafine was the most commonly prescribed antifungal agent, followed by systemic fluconazole, systemic itraconazole, and topical ciclopirox (Figure 5). Over the 18-year study period, there was an increasing trend in the frequency of terbinafine prescription (regression coefficient [r]=0.01319; P=.004); a decreasing trend for fluconazole (r=-0.0053851; P=.04), itraconazole (r=-0.0113988; P<.001), griseofulvin (r=-0.0073942; P<.001), and econazole prescription (r=-0.0032405; P=.01); and no significant trend for ketoconazole (r=-0.0034553; P=.1), naftifine (r=-0.0029067; P=.06), sulconazole (r=-0.0001619; P=.8), ciclopirox (r=0.0032684; P=.1), and miconazole prescription (r=0.0002074; P=.5).

Eighty-six percent of visits were for established patients who had been seen in the related office with any diagnosis before the recorded visit and 14% of visits were for new (first-time) patients. Fluconazole was the most frequently used antifungal drug for new patients, while terbinafine was the most frequently used in other visits. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug by general and family practitioners, dermatologists, internal medicine practitioners, and all other specialties not listed.

Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug in both genders and in white and black patients. Itraconazole was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for Hispanic patients and those of other ethnicities not listed. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for patients with diabetes and obesity (ie, body mass index ≥30). In 19,330,000 of 19,350,000 total estimated visits included in this study, onychomycosis was the only diagnosis with a potential indication for an antifungal drug therapy, ruling out the possibility that fluconazole or other drugs were used for patients who also had candidiasis or “other specified erythematous conditions.”

Discussion

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails that is more prevalent in older age groups, with equal prevalence in both genders and a higher prevalence in males. The NAMCS data showed higher rates of onychomycosis visits among older age groups, which is in agreement with results from prior studies.16,17 In the current study, we observed a higher prevalence of onychomycosis visits among females as well as white and Hispanic patients. These results may be due to a higher prevalence of onychomycosis in these populations or simply a result of difference in socioeconomic level or importance of aesthetics. Although there are limited data regarding the prevalence of onychomycosis among different races and ethnicities in the United States, a high incidence of onychomycosis has been reported in Mexico.18

Repeated trauma to the great toenail from ill-fitting shoes is a predisposing factor for onychomycosis.16 In the current study, ingrown nails were among the most common comorbidities found in onychomycosis patients. Although nail dystrophy caused by onychomycosis may lead to ingrown nails, it also is possible that both conditions may be caused by trauma.

Patients with immunodeficiencies (eg, diabetes) may be predisposed to onychomycosis as well as its associated complications and morbidities (eg, cellulitis).16,19 Diabetes affects 4% to 22% of patients with onychomycosis in different populations, including Denmark, Mexico, and India.18,20,21 In our study, diabetes was among the most common recorded comorbidities reported during onychomycosis visits, with a prevalence of 3.4%. It is likely that many more visits involved patients with diabetes that had not been diagnosed or reported. With the increased risk for complications with diabetes, it is important for physicians to treat these patients when they have a nail infection.

The available systemic therapies for treatment of onychomycosis include griseofulvin, allylamines, and imidazoles. Comparison of griseofulvin with newer systemic antifungal agents such as terbinafine and itraconazole suggests that griseofulvin has lower efficacy and therefore is not a first-line treatment of onychomycosis.1 Terbinafine is the most active of the currently available antidermatophyte drugs both in vitro and in vivo, with synergistic effects with imidazoles and ciclopirox.1,22-27 A combination of topical and systemic therapies may improve cure rates of onychomycosis or possibly shorten the duration of therapy with the systemic agent.1,2 Treatment strategies can vary according to the specialty of the treating physician, with general practitioners often preferring monotherapies and dermatologists preferring combination therapies.28 In Europe, the most commonly prescribed medication for onychomycosis was topical amorolfine followed by systemic terbinafine and itraconazole.28 In the current study, we could not separate data for topical versus systemic terbinafine because the NAMCS uses similar names for reporting the drug; however, the rates of prescription for allylamines and imidazoles were nearly equal (Figure 5), with terbinafine showing an increased use over time as opposed to a decreased use of imidazoles. Although fluconazole is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of onychomycosis, oral fluconazole was the second most common treatment prescribed in our study. Griseofulvin, which is not considered as a drug of choice in onychomycosis,1 was prescribed in a small fraction of the visits, with a decreasing trend of usage over time.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the NAMCS data revealed that the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States is in accordance with recommendations in current guidelines. An encouraging finding was the notable downward trend in use of griseofulvin, suggesting that health care providers are changing practice to meet standard of care. Increased efforts must be made to uniformly modify practices in compliance with evidence-based recommendations and to minimize unnecessary risk and cost associated with use of drugs with lower efficacy.

1. Roberts DT, Taylor WD, Boyle J; British Association of Dermatologists. Guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:402-410.

2. Seebacher C, Brasch J, Abeck D, et al. Onychomycosis. Mycoses. 2007;50:321-327.

3. Summerbell RC, Kane J, Krajden S. Onychomycosis, tinea pedis and tinea manuum caused by non-dermatophytic filamentous fungi. Mycoses. 1989;32:609-619.

4. Murray SC, Dawber RP. Onychomycosis of toenails: orthopaedic and podiatric considerations. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:105-112.

5. Achten G, Wanet-Rouard J. Onychomycoses in the laboratory. Mykosen Suppl. 1978;1:125-127.

6. Haneke E, Roseeuw D. The scope of onychomycosis: epidemiology and clinical features. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(suppl 2):7-12.

7. Haneke E. Fungal infections of the nail. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:41-53.

8. Karmakar S, Kalla G, Joshi KR, et al. Dermatophytoses in a desert district of Western Rajasthan. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1995;61:280-283.

9. Drake LA. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: onychomycosis. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:116-121.

10. Roberts DT. Prevalence of dermatophyte onychomycosis in the United Kingdom: results of an omnibus survey. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126(suppl 39):23-27.

11. Drake LA, Scher RK, Smith EB, et al. Effect of onychomycosis on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5 pt 1):702-704.

12. Detandt M, Nolard N. Fungal contamination of the floors of swimming pools, particularly subtropical swimming paradises. Mycoses. 1995;38:509-513.

13. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

14. Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR, Bradham DD. Office-based physician services provided by dermatologists in the United States in 1990. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:93-97.

15. 2001 NAMCS Micro-Data File Documentation. http://www.nber.org/namcs/docs/namcs2001.pdf. National Bureau of Economic Research Web site. Accessed April 27, 2015.

16. Williams HC. The epidemiology of onychomycosis in Britain. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:101-109.

17. Elewski BE, Charif MA. Prevalence of onychomycosis in patients attending a dermatology clinic in northeastern Ohio for other conditions. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1172-1173.

18. Arenas R, Bonifaz A, Padilla MC, et al. Onychomycosis. a Mexican survey. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:611-614.

19. Faergemann J, Baran R. Epidemiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl 65):1-4.

20. Sarma S, Capoor MR, Deb M, et al. Epidemiologic and clinicomycologic profile of onychomycosis from north India. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:584-587.

21. Svejgaard EL, Nilsson J. Onychomycosis in Denmark: prevalence of fungal nail infection in general practice. Mycoses. 2004;47:131-135.

22. Santos DA, Hamdan JS. In vitro antifungal oral drug and drug-combination activity against onychomycosis causative dermatophytes. Med Mycol. 2006;44:357-362.

23. Gupta AK, Kohli Y. In vitro susceptibility testing of ciclopirox, terbinafine, ketoconazole and itraconazole against dermatophytes and nondermatophytes, and in vitro evaluation of combination antifungal activity. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:296-305.

24. Gupta AK, Lynch LE. Management of onychomycosis: examining the role of monotherapy and dual, triple, or quadruple therapies. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 1):5-9.

25. Harman S, Ashbee HR, Evans EG. Testing of antifungal combinations against yeasts and dermatophytes. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:104-107.

26. Spader TB, Venturini TP, Rossato L, et al. Synergisms of voriconazole or itraconazole combined with other antifungal agents against Fusarium spp. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2013;30:200-204.

27. Biancalana FS, Lyra L, Moretti ML, et al. Susceptibility testing of terbinafine alone and in combination with amphotericin B, itraconazole, or voriconazole against conidia and hyphae of dematiaceous molds. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71:378-385.

28. Effendy I, Lecha M, Feuilhade de CM, et al. Epidemiology and clinical classification of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(suppl 1):8-12.

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails caused by dermatophytes, nondermatophyte molds, and yeasts, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common causative organism.1-3 Onychomycosis affects approximately 2% to 26% of different populations worldwide. It represents 20% to 50% of onychopathies and approximately 30% of fungal cutaneous infections.4-9 Less than 30% of infected persons seek medical advice or treatment even in developed areas of the world.10 Onychomycosis may be a source of more widespread fungal skin infections or give rise to complications such as cellulitis. Chronic, long-lasting infection may result in nail dystrophy and can lead to pain, absence from work, and decreased quality of life.1,11 Because the dermatophyte can contaminate communal bathing facilities and spread to others,12 it is important to effectively target and treat patients with onychomycosis, thus reducing the rate of related morbidities.1,9

The primary aim of onychomycosis treatment is to cure the infection and prevent relapse. Both topical and oral agents are available for the treatment of fungal nail infections. Generally, systemic therapy for onychomycosis is more successful than topical treatment, likely due to poor penetration of topical medications into the nail plate.1,2,9 However, newer topical drugs have shown promising results in treating some types of onychomycosis.13 In its guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis, the British Association of Dermatologists recommends use of topical treatment under the following conditions: (1) when there is not extensive involvement of the nail plate (eg, candidal paronychia, superficial white onychomycosis, early stages of distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis), (2) when systemic therapy is contraindicated, or (3) in combination with systemic therapy.1 Although there are multiple treatments for fungal nail infections, there are limited reports on the ways in which physicians actually use these treatments or the frequency with which they prescribe them.

This study provides a representative portrayal of onychomycosis visits in the US outpatient setting using a large nationally sampled survey. In particular, we aimed to assess the number of visits related to onychomycosis, the demographics of patients, and the treatments being prescribed for onychomycosis.

Methods

Study Design

Data from January 1, 1993, to December 31, 2010, were collected from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), an ongoing survey of nonfederal employed US office-based physicians who are primarily engaged in direct patient care. The NAMCS has been conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics every year since 1989 to estimate the utilization of ambulatory care services in the United States. Since 1989 including 1993 to 2010, the NAMCS sampled approximately 30,000 visits per year. For each visit sampled, a 1-page patient log including demographic data, physicians’ diagnoses, services provided, and medications was completed. In the NAMCS survey, visits were divided into 2 groups: (1) visits from established patients that have been seen in that office before for any reason, and (2) visits for new (ie, first-time) patients. The current study included all visits in which fungal nail infection (code 110.1 according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]) was listed as 1 of 3 possible diagnoses.

Statistical Analysis

Sampling weights were applied to data to produce estimates for the total US outpatient setting.14 Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2, and SAS survey analysis procedures were used to account for the clustered sampling of the survey. The total numbers of visits for which onychomycosis was 1 of 3 possible diagnoses and for which it was the sole diagnosis were reported. Visit rates per population by demographic characteristics (ie, patient sex, age, race, and ethnicity) were calculated. Population estimates were based on the 2001 NAMCS Public Micro-Data File Documentation records of the US census estimates for noninstitutionalized civilian persons.15 Trends in proportion of visits linked with an onychomycosis diagnosis over time were evaluated using the SAS SURVEYREG procedure. Types of physicians who attended to these visits as well as leading comorbidities that had been diagnosed and documented in the medical record were characterized. Onychomycosis-related medications prescribed at these visits were reported and prescribing trends over time were evaluated. Differences in the treatment prescribed according to the type of visit (ie, first-time or return visit); physician specialty; and patients’ gender, race, and health conditions (eg, obesity, diabetes mellitus) were examined. To exclude the possibility that fluconazole and other broad-spectrum antifungals were being used for secondary diagnoses, we determined the number of visits that had an additional diagnosis of either candidiasis (ICD-9 codes 112.0–112.9) or “other specified erythematous conditions” (ICD-9 code 695.89).

Results

During the 18-year study period, 636 visits with a diagnosis of onychomycosis were recorded in the NAMCS database. This unweighted number of visits corresponded with approximately 19,350,000 visits (an average of 1,075,000 visits per year) to physicians’ offices with a diagnosis of onychomycosis in the United States during this period. Among these visits, there were an estimated 4,250,000 visits with fungal nail infection as the only diagnosis (no other comorbidities recorded). The recorded visits included more female (57.6%) than male (42.4%) patients, and 85% of patients were white (Table). Patients aged 35 to 44 years accounted for the largest number of visits; however, the estimated rate of onychomycosis visits per 100,000 US citizens was highest among those aged 65 to 74 years (Figure 1).

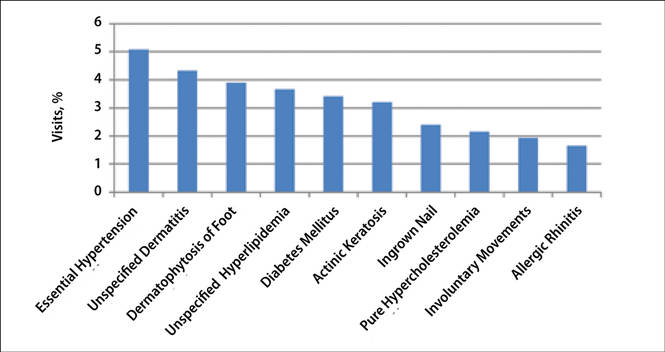

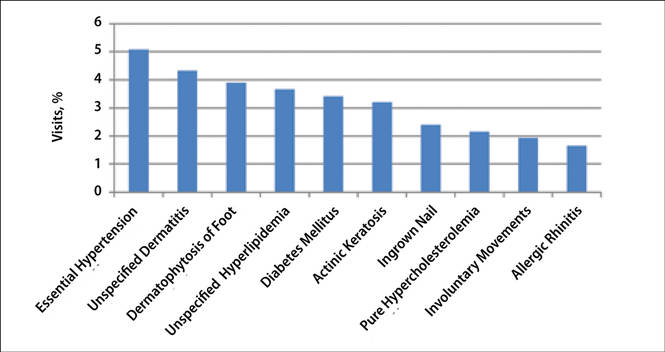

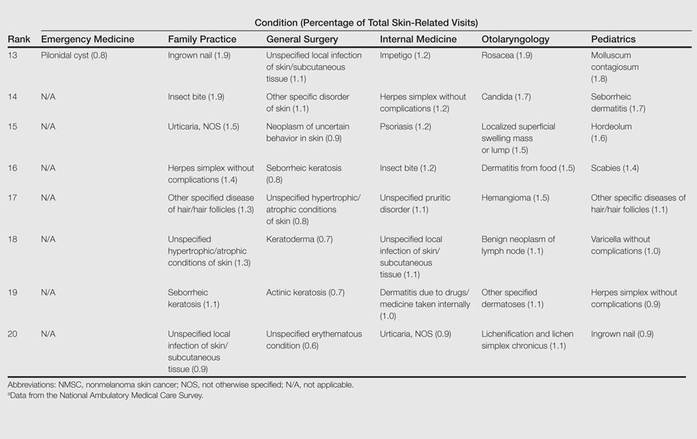

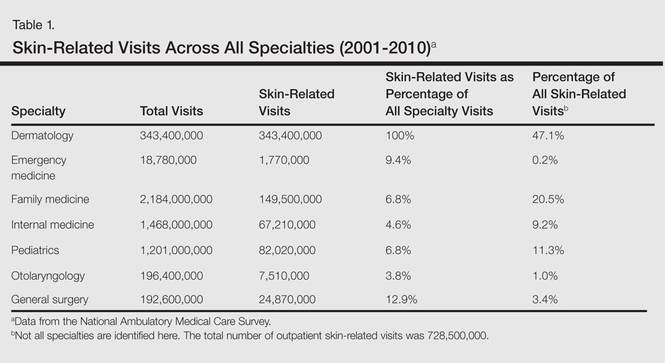

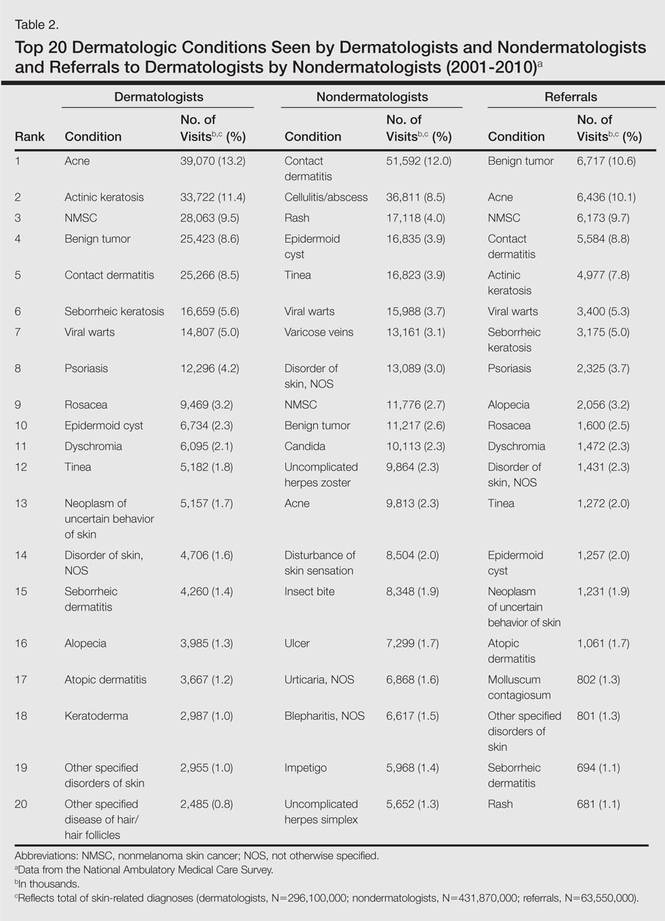

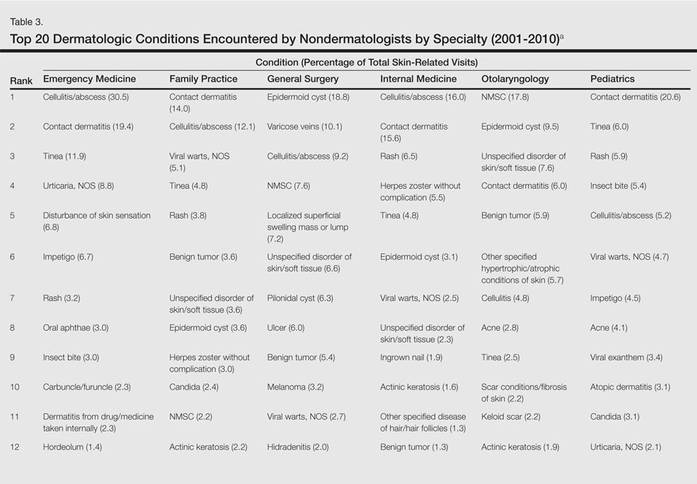

The number of US outpatient visits with a recorded diagnosis of onychomycosis increased from 1993 to 2010 (Figure 2); however, there was no change in the ratio of onychomycosis visits to the total number of recorded visits in NAMCS database during the study period (P=.9). A combined total of 91% of onychomycosis visits were to general and family practitioners, dermatologists, or internal medicine practitioners (Figure 3). Although cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus accounted for a large proportion of comorbidities, conditions affecting the feet (eg, tinea pedis, ingrown nails) also were among the most common comorbidities (Figure 4).

|

In both topical and systemic form, terbinafine was the most commonly prescribed antifungal agent, followed by systemic fluconazole, systemic itraconazole, and topical ciclopirox (Figure 5). Over the 18-year study period, there was an increasing trend in the frequency of terbinafine prescription (regression coefficient [r]=0.01319; P=.004); a decreasing trend for fluconazole (r=-0.0053851; P=.04), itraconazole (r=-0.0113988; P<.001), griseofulvin (r=-0.0073942; P<.001), and econazole prescription (r=-0.0032405; P=.01); and no significant trend for ketoconazole (r=-0.0034553; P=.1), naftifine (r=-0.0029067; P=.06), sulconazole (r=-0.0001619; P=.8), ciclopirox (r=0.0032684; P=.1), and miconazole prescription (r=0.0002074; P=.5).

Eighty-six percent of visits were for established patients who had been seen in the related office with any diagnosis before the recorded visit and 14% of visits were for new (first-time) patients. Fluconazole was the most frequently used antifungal drug for new patients, while terbinafine was the most frequently used in other visits. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug by general and family practitioners, dermatologists, internal medicine practitioners, and all other specialties not listed.

Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug in both genders and in white and black patients. Itraconazole was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for Hispanic patients and those of other ethnicities not listed. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for patients with diabetes and obesity (ie, body mass index ≥30). In 19,330,000 of 19,350,000 total estimated visits included in this study, onychomycosis was the only diagnosis with a potential indication for an antifungal drug therapy, ruling out the possibility that fluconazole or other drugs were used for patients who also had candidiasis or “other specified erythematous conditions.”

Discussion

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails that is more prevalent in older age groups, with equal prevalence in both genders and a higher prevalence in males. The NAMCS data showed higher rates of onychomycosis visits among older age groups, which is in agreement with results from prior studies.16,17 In the current study, we observed a higher prevalence of onychomycosis visits among females as well as white and Hispanic patients. These results may be due to a higher prevalence of onychomycosis in these populations or simply a result of difference in socioeconomic level or importance of aesthetics. Although there are limited data regarding the prevalence of onychomycosis among different races and ethnicities in the United States, a high incidence of onychomycosis has been reported in Mexico.18

Repeated trauma to the great toenail from ill-fitting shoes is a predisposing factor for onychomycosis.16 In the current study, ingrown nails were among the most common comorbidities found in onychomycosis patients. Although nail dystrophy caused by onychomycosis may lead to ingrown nails, it also is possible that both conditions may be caused by trauma.

Patients with immunodeficiencies (eg, diabetes) may be predisposed to onychomycosis as well as its associated complications and morbidities (eg, cellulitis).16,19 Diabetes affects 4% to 22% of patients with onychomycosis in different populations, including Denmark, Mexico, and India.18,20,21 In our study, diabetes was among the most common recorded comorbidities reported during onychomycosis visits, with a prevalence of 3.4%. It is likely that many more visits involved patients with diabetes that had not been diagnosed or reported. With the increased risk for complications with diabetes, it is important for physicians to treat these patients when they have a nail infection.

The available systemic therapies for treatment of onychomycosis include griseofulvin, allylamines, and imidazoles. Comparison of griseofulvin with newer systemic antifungal agents such as terbinafine and itraconazole suggests that griseofulvin has lower efficacy and therefore is not a first-line treatment of onychomycosis.1 Terbinafine is the most active of the currently available antidermatophyte drugs both in vitro and in vivo, with synergistic effects with imidazoles and ciclopirox.1,22-27 A combination of topical and systemic therapies may improve cure rates of onychomycosis or possibly shorten the duration of therapy with the systemic agent.1,2 Treatment strategies can vary according to the specialty of the treating physician, with general practitioners often preferring monotherapies and dermatologists preferring combination therapies.28 In Europe, the most commonly prescribed medication for onychomycosis was topical amorolfine followed by systemic terbinafine and itraconazole.28 In the current study, we could not separate data for topical versus systemic terbinafine because the NAMCS uses similar names for reporting the drug; however, the rates of prescription for allylamines and imidazoles were nearly equal (Figure 5), with terbinafine showing an increased use over time as opposed to a decreased use of imidazoles. Although fluconazole is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of onychomycosis, oral fluconazole was the second most common treatment prescribed in our study. Griseofulvin, which is not considered as a drug of choice in onychomycosis,1 was prescribed in a small fraction of the visits, with a decreasing trend of usage over time.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the NAMCS data revealed that the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States is in accordance with recommendations in current guidelines. An encouraging finding was the notable downward trend in use of griseofulvin, suggesting that health care providers are changing practice to meet standard of care. Increased efforts must be made to uniformly modify practices in compliance with evidence-based recommendations and to minimize unnecessary risk and cost associated with use of drugs with lower efficacy.

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails caused by dermatophytes, nondermatophyte molds, and yeasts, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common causative organism.1-3 Onychomycosis affects approximately 2% to 26% of different populations worldwide. It represents 20% to 50% of onychopathies and approximately 30% of fungal cutaneous infections.4-9 Less than 30% of infected persons seek medical advice or treatment even in developed areas of the world.10 Onychomycosis may be a source of more widespread fungal skin infections or give rise to complications such as cellulitis. Chronic, long-lasting infection may result in nail dystrophy and can lead to pain, absence from work, and decreased quality of life.1,11 Because the dermatophyte can contaminate communal bathing facilities and spread to others,12 it is important to effectively target and treat patients with onychomycosis, thus reducing the rate of related morbidities.1,9

The primary aim of onychomycosis treatment is to cure the infection and prevent relapse. Both topical and oral agents are available for the treatment of fungal nail infections. Generally, systemic therapy for onychomycosis is more successful than topical treatment, likely due to poor penetration of topical medications into the nail plate.1,2,9 However, newer topical drugs have shown promising results in treating some types of onychomycosis.13 In its guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis, the British Association of Dermatologists recommends use of topical treatment under the following conditions: (1) when there is not extensive involvement of the nail plate (eg, candidal paronychia, superficial white onychomycosis, early stages of distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis), (2) when systemic therapy is contraindicated, or (3) in combination with systemic therapy.1 Although there are multiple treatments for fungal nail infections, there are limited reports on the ways in which physicians actually use these treatments or the frequency with which they prescribe them.

This study provides a representative portrayal of onychomycosis visits in the US outpatient setting using a large nationally sampled survey. In particular, we aimed to assess the number of visits related to onychomycosis, the demographics of patients, and the treatments being prescribed for onychomycosis.

Methods

Study Design

Data from January 1, 1993, to December 31, 2010, were collected from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), an ongoing survey of nonfederal employed US office-based physicians who are primarily engaged in direct patient care. The NAMCS has been conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics every year since 1989 to estimate the utilization of ambulatory care services in the United States. Since 1989 including 1993 to 2010, the NAMCS sampled approximately 30,000 visits per year. For each visit sampled, a 1-page patient log including demographic data, physicians’ diagnoses, services provided, and medications was completed. In the NAMCS survey, visits were divided into 2 groups: (1) visits from established patients that have been seen in that office before for any reason, and (2) visits for new (ie, first-time) patients. The current study included all visits in which fungal nail infection (code 110.1 according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]) was listed as 1 of 3 possible diagnoses.

Statistical Analysis

Sampling weights were applied to data to produce estimates for the total US outpatient setting.14 Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2, and SAS survey analysis procedures were used to account for the clustered sampling of the survey. The total numbers of visits for which onychomycosis was 1 of 3 possible diagnoses and for which it was the sole diagnosis were reported. Visit rates per population by demographic characteristics (ie, patient sex, age, race, and ethnicity) were calculated. Population estimates were based on the 2001 NAMCS Public Micro-Data File Documentation records of the US census estimates for noninstitutionalized civilian persons.15 Trends in proportion of visits linked with an onychomycosis diagnosis over time were evaluated using the SAS SURVEYREG procedure. Types of physicians who attended to these visits as well as leading comorbidities that had been diagnosed and documented in the medical record were characterized. Onychomycosis-related medications prescribed at these visits were reported and prescribing trends over time were evaluated. Differences in the treatment prescribed according to the type of visit (ie, first-time or return visit); physician specialty; and patients’ gender, race, and health conditions (eg, obesity, diabetes mellitus) were examined. To exclude the possibility that fluconazole and other broad-spectrum antifungals were being used for secondary diagnoses, we determined the number of visits that had an additional diagnosis of either candidiasis (ICD-9 codes 112.0–112.9) or “other specified erythematous conditions” (ICD-9 code 695.89).

Results

During the 18-year study period, 636 visits with a diagnosis of onychomycosis were recorded in the NAMCS database. This unweighted number of visits corresponded with approximately 19,350,000 visits (an average of 1,075,000 visits per year) to physicians’ offices with a diagnosis of onychomycosis in the United States during this period. Among these visits, there were an estimated 4,250,000 visits with fungal nail infection as the only diagnosis (no other comorbidities recorded). The recorded visits included more female (57.6%) than male (42.4%) patients, and 85% of patients were white (Table). Patients aged 35 to 44 years accounted for the largest number of visits; however, the estimated rate of onychomycosis visits per 100,000 US citizens was highest among those aged 65 to 74 years (Figure 1).

The number of US outpatient visits with a recorded diagnosis of onychomycosis increased from 1993 to 2010 (Figure 2); however, there was no change in the ratio of onychomycosis visits to the total number of recorded visits in NAMCS database during the study period (P=.9). A combined total of 91% of onychomycosis visits were to general and family practitioners, dermatologists, or internal medicine practitioners (Figure 3). Although cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus accounted for a large proportion of comorbidities, conditions affecting the feet (eg, tinea pedis, ingrown nails) also were among the most common comorbidities (Figure 4).

|

In both topical and systemic form, terbinafine was the most commonly prescribed antifungal agent, followed by systemic fluconazole, systemic itraconazole, and topical ciclopirox (Figure 5). Over the 18-year study period, there was an increasing trend in the frequency of terbinafine prescription (regression coefficient [r]=0.01319; P=.004); a decreasing trend for fluconazole (r=-0.0053851; P=.04), itraconazole (r=-0.0113988; P<.001), griseofulvin (r=-0.0073942; P<.001), and econazole prescription (r=-0.0032405; P=.01); and no significant trend for ketoconazole (r=-0.0034553; P=.1), naftifine (r=-0.0029067; P=.06), sulconazole (r=-0.0001619; P=.8), ciclopirox (r=0.0032684; P=.1), and miconazole prescription (r=0.0002074; P=.5).

Eighty-six percent of visits were for established patients who had been seen in the related office with any diagnosis before the recorded visit and 14% of visits were for new (first-time) patients. Fluconazole was the most frequently used antifungal drug for new patients, while terbinafine was the most frequently used in other visits. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug by general and family practitioners, dermatologists, internal medicine practitioners, and all other specialties not listed.

Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug in both genders and in white and black patients. Itraconazole was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for Hispanic patients and those of other ethnicities not listed. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for patients with diabetes and obesity (ie, body mass index ≥30). In 19,330,000 of 19,350,000 total estimated visits included in this study, onychomycosis was the only diagnosis with a potential indication for an antifungal drug therapy, ruling out the possibility that fluconazole or other drugs were used for patients who also had candidiasis or “other specified erythematous conditions.”

Discussion

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails that is more prevalent in older age groups, with equal prevalence in both genders and a higher prevalence in males. The NAMCS data showed higher rates of onychomycosis visits among older age groups, which is in agreement with results from prior studies.16,17 In the current study, we observed a higher prevalence of onychomycosis visits among females as well as white and Hispanic patients. These results may be due to a higher prevalence of onychomycosis in these populations or simply a result of difference in socioeconomic level or importance of aesthetics. Although there are limited data regarding the prevalence of onychomycosis among different races and ethnicities in the United States, a high incidence of onychomycosis has been reported in Mexico.18

Repeated trauma to the great toenail from ill-fitting shoes is a predisposing factor for onychomycosis.16 In the current study, ingrown nails were among the most common comorbidities found in onychomycosis patients. Although nail dystrophy caused by onychomycosis may lead to ingrown nails, it also is possible that both conditions may be caused by trauma.

Patients with immunodeficiencies (eg, diabetes) may be predisposed to onychomycosis as well as its associated complications and morbidities (eg, cellulitis).16,19 Diabetes affects 4% to 22% of patients with onychomycosis in different populations, including Denmark, Mexico, and India.18,20,21 In our study, diabetes was among the most common recorded comorbidities reported during onychomycosis visits, with a prevalence of 3.4%. It is likely that many more visits involved patients with diabetes that had not been diagnosed or reported. With the increased risk for complications with diabetes, it is important for physicians to treat these patients when they have a nail infection.

The available systemic therapies for treatment of onychomycosis include griseofulvin, allylamines, and imidazoles. Comparison of griseofulvin with newer systemic antifungal agents such as terbinafine and itraconazole suggests that griseofulvin has lower efficacy and therefore is not a first-line treatment of onychomycosis.1 Terbinafine is the most active of the currently available antidermatophyte drugs both in vitro and in vivo, with synergistic effects with imidazoles and ciclopirox.1,22-27 A combination of topical and systemic therapies may improve cure rates of onychomycosis or possibly shorten the duration of therapy with the systemic agent.1,2 Treatment strategies can vary according to the specialty of the treating physician, with general practitioners often preferring monotherapies and dermatologists preferring combination therapies.28 In Europe, the most commonly prescribed medication for onychomycosis was topical amorolfine followed by systemic terbinafine and itraconazole.28 In the current study, we could not separate data for topical versus systemic terbinafine because the NAMCS uses similar names for reporting the drug; however, the rates of prescription for allylamines and imidazoles were nearly equal (Figure 5), with terbinafine showing an increased use over time as opposed to a decreased use of imidazoles. Although fluconazole is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of onychomycosis, oral fluconazole was the second most common treatment prescribed in our study. Griseofulvin, which is not considered as a drug of choice in onychomycosis,1 was prescribed in a small fraction of the visits, with a decreasing trend of usage over time.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the NAMCS data revealed that the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States is in accordance with recommendations in current guidelines. An encouraging finding was the notable downward trend in use of griseofulvin, suggesting that health care providers are changing practice to meet standard of care. Increased efforts must be made to uniformly modify practices in compliance with evidence-based recommendations and to minimize unnecessary risk and cost associated with use of drugs with lower efficacy.

1. Roberts DT, Taylor WD, Boyle J; British Association of Dermatologists. Guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:402-410.

2. Seebacher C, Brasch J, Abeck D, et al. Onychomycosis. Mycoses. 2007;50:321-327.

3. Summerbell RC, Kane J, Krajden S. Onychomycosis, tinea pedis and tinea manuum caused by non-dermatophytic filamentous fungi. Mycoses. 1989;32:609-619.

4. Murray SC, Dawber RP. Onychomycosis of toenails: orthopaedic and podiatric considerations. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:105-112.

5. Achten G, Wanet-Rouard J. Onychomycoses in the laboratory. Mykosen Suppl. 1978;1:125-127.

6. Haneke E, Roseeuw D. The scope of onychomycosis: epidemiology and clinical features. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(suppl 2):7-12.

7. Haneke E. Fungal infections of the nail. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:41-53.

8. Karmakar S, Kalla G, Joshi KR, et al. Dermatophytoses in a desert district of Western Rajasthan. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1995;61:280-283.

9. Drake LA. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: onychomycosis. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:116-121.

10. Roberts DT. Prevalence of dermatophyte onychomycosis in the United Kingdom: results of an omnibus survey. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126(suppl 39):23-27.

11. Drake LA, Scher RK, Smith EB, et al. Effect of onychomycosis on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5 pt 1):702-704.

12. Detandt M, Nolard N. Fungal contamination of the floors of swimming pools, particularly subtropical swimming paradises. Mycoses. 1995;38:509-513.

13. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

14. Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR, Bradham DD. Office-based physician services provided by dermatologists in the United States in 1990. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:93-97.

15. 2001 NAMCS Micro-Data File Documentation. http://www.nber.org/namcs/docs/namcs2001.pdf. National Bureau of Economic Research Web site. Accessed April 27, 2015.

16. Williams HC. The epidemiology of onychomycosis in Britain. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:101-109.

17. Elewski BE, Charif MA. Prevalence of onychomycosis in patients attending a dermatology clinic in northeastern Ohio for other conditions. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1172-1173.

18. Arenas R, Bonifaz A, Padilla MC, et al. Onychomycosis. a Mexican survey. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:611-614.

19. Faergemann J, Baran R. Epidemiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl 65):1-4.

20. Sarma S, Capoor MR, Deb M, et al. Epidemiologic and clinicomycologic profile of onychomycosis from north India. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:584-587.

21. Svejgaard EL, Nilsson J. Onychomycosis in Denmark: prevalence of fungal nail infection in general practice. Mycoses. 2004;47:131-135.

22. Santos DA, Hamdan JS. In vitro antifungal oral drug and drug-combination activity against onychomycosis causative dermatophytes. Med Mycol. 2006;44:357-362.

23. Gupta AK, Kohli Y. In vitro susceptibility testing of ciclopirox, terbinafine, ketoconazole and itraconazole against dermatophytes and nondermatophytes, and in vitro evaluation of combination antifungal activity. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:296-305.

24. Gupta AK, Lynch LE. Management of onychomycosis: examining the role of monotherapy and dual, triple, or quadruple therapies. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 1):5-9.

25. Harman S, Ashbee HR, Evans EG. Testing of antifungal combinations against yeasts and dermatophytes. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:104-107.

26. Spader TB, Venturini TP, Rossato L, et al. Synergisms of voriconazole or itraconazole combined with other antifungal agents against Fusarium spp. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2013;30:200-204.

27. Biancalana FS, Lyra L, Moretti ML, et al. Susceptibility testing of terbinafine alone and in combination with amphotericin B, itraconazole, or voriconazole against conidia and hyphae of dematiaceous molds. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71:378-385.

28. Effendy I, Lecha M, Feuilhade de CM, et al. Epidemiology and clinical classification of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(suppl 1):8-12.

1. Roberts DT, Taylor WD, Boyle J; British Association of Dermatologists. Guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:402-410.

2. Seebacher C, Brasch J, Abeck D, et al. Onychomycosis. Mycoses. 2007;50:321-327.

3. Summerbell RC, Kane J, Krajden S. Onychomycosis, tinea pedis and tinea manuum caused by non-dermatophytic filamentous fungi. Mycoses. 1989;32:609-619.

4. Murray SC, Dawber RP. Onychomycosis of toenails: orthopaedic and podiatric considerations. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:105-112.

5. Achten G, Wanet-Rouard J. Onychomycoses in the laboratory. Mykosen Suppl. 1978;1:125-127.

6. Haneke E, Roseeuw D. The scope of onychomycosis: epidemiology and clinical features. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(suppl 2):7-12.

7. Haneke E. Fungal infections of the nail. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:41-53.

8. Karmakar S, Kalla G, Joshi KR, et al. Dermatophytoses in a desert district of Western Rajasthan. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1995;61:280-283.

9. Drake LA. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: onychomycosis. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:116-121.

10. Roberts DT. Prevalence of dermatophyte onychomycosis in the United Kingdom: results of an omnibus survey. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126(suppl 39):23-27.

11. Drake LA, Scher RK, Smith EB, et al. Effect of onychomycosis on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5 pt 1):702-704.

12. Detandt M, Nolard N. Fungal contamination of the floors of swimming pools, particularly subtropical swimming paradises. Mycoses. 1995;38:509-513.

13. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

14. Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR, Bradham DD. Office-based physician services provided by dermatologists in the United States in 1990. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:93-97.

15. 2001 NAMCS Micro-Data File Documentation. http://www.nber.org/namcs/docs/namcs2001.pdf. National Bureau of Economic Research Web site. Accessed April 27, 2015.

16. Williams HC. The epidemiology of onychomycosis in Britain. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:101-109.

17. Elewski BE, Charif MA. Prevalence of onychomycosis in patients attending a dermatology clinic in northeastern Ohio for other conditions. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1172-1173.

18. Arenas R, Bonifaz A, Padilla MC, et al. Onychomycosis. a Mexican survey. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:611-614.

19. Faergemann J, Baran R. Epidemiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl 65):1-4.

20. Sarma S, Capoor MR, Deb M, et al. Epidemiologic and clinicomycologic profile of onychomycosis from north India. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:584-587.

21. Svejgaard EL, Nilsson J. Onychomycosis in Denmark: prevalence of fungal nail infection in general practice. Mycoses. 2004;47:131-135.

22. Santos DA, Hamdan JS. In vitro antifungal oral drug and drug-combination activity against onychomycosis causative dermatophytes. Med Mycol. 2006;44:357-362.

23. Gupta AK, Kohli Y. In vitro susceptibility testing of ciclopirox, terbinafine, ketoconazole and itraconazole against dermatophytes and nondermatophytes, and in vitro evaluation of combination antifungal activity. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:296-305.

24. Gupta AK, Lynch LE. Management of onychomycosis: examining the role of monotherapy and dual, triple, or quadruple therapies. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 1):5-9.

25. Harman S, Ashbee HR, Evans EG. Testing of antifungal combinations against yeasts and dermatophytes. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:104-107.

26. Spader TB, Venturini TP, Rossato L, et al. Synergisms of voriconazole or itraconazole combined with other antifungal agents against Fusarium spp. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2013;30:200-204.

27. Biancalana FS, Lyra L, Moretti ML, et al. Susceptibility testing of terbinafine alone and in combination with amphotericin B, itraconazole, or voriconazole against conidia and hyphae of dematiaceous molds. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71:378-385.

28. Effendy I, Lecha M, Feuilhade de CM, et al. Epidemiology and clinical classification of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(suppl 1):8-12.

Practice Points

- Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails that may result in remarkable morbidity. Effective treatment may reduce the rate of transmission and related morbidities.

- Onychomycosis is most commonly found in patients older than 35 years.

- Terbinafine has been the most commonly prescribed antifungal agent for onychomycosis in the United States between 1993 and 2010, followed by systemic fluconazole, systemic itraconazole, and topical ciclopirox.

The Rosacea Patient Journey: A Novel Approach to Conceptualizing Patient Experiences

Rosacea patients experience symptoms ranging from flushing to persistent acnelike rashes that can cause low self-esteem and anxiety, leading to social and professional isolation.1 Although it is estimated that 16 million individuals in the United States have rosacea, only 10% seek treatment.2,3 The motivation for patients to seek and adhere to treatment is not well characterized.

A patient journey is a map of the steps a patient takes as he/she progresses through different segments of the disease from diagnosis to management, including all the influences that can push him/her toward or away from certain decisions. The patient journey model provides a structure for understanding key issues in rosacea management, including barriers to successful treatment outcomes.

The patient journey model progresses from development of disease and diagnosis to treatment and disease management (Figure). We sought to examine each step of the rosacea patient journey to better understand key patient care boundaries faced by rosacea patients. We assessed the current literature regarding each step of the patient experience and identified areas of the patient journey with limited research.

Click here to view the figure as a PDF to print for future reference.

Researching the Patient Experience

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a search of the National Rosacea Society Web site (http://www.rosacea.org) were conducted to identify articles and materials that quantitatively or qualitatively described rosacea patient experiences. Search terms included rosacea, rosacea patient experience, rosacea treatment, rosacea adherence, and rosacea quality of life. A Google search also was conducted using the same terms to obtain current news articles online. Current literature pertaining to the patient journey was summarized.

To create a model for the rosacea patient journey, we refined a rheumatoid arthritis patient journey map4 and included the critical components of the journey for rosacea patients. We organized the journey into stages, including prediagnosis, diagnosis, treatment, adherence, and management. We first explored what occurs prior to diagnosis, which includes the patient’s symptoms before visiting a physician. We then examined the process of diagnosis and the implementation of a treatment plan. Treatment adherence was then explored, ending with the ways patients self-manage their disease beyond the physician’s office.

Prediagnosis: What Motivates Patients to Seek Treatment

Rosacea can present with many symptoms that may lead patients to see a physician, including facial erythema and telangiectases, papules and pustules, phymatous changes, and ocular manifestations.5 The most common concern is temporary facial flushing, followed by persistent redness, then bumps and pimples.6 Many patients seek treatment after persistent facial flushing and an intolerable burning sensation. Some middle-aged patients decide to see a dermatologist for the first time when they break out in acne lesions after a history of clear skin. Others seek treatment because they can no longer tolerate the pain and embarrassment associated with their symptoms. However, patients who seek treatment only account for a small proportion of patients with rosacea, as only 10% of patients seek conventional medical treatment.7 Furthermore, symptomatic patients on average wait 7 months to 5 years before receiving a diagnosis.8,9

Care often is delayed or not pursued because many rosacea symptoms are mild when they first appear and may not initially bother the patient. Patients may not think anything of their symptoms and dismiss them as either acne vulgaris or sunburn. Due to the relapsing and remitting nature of the disease course, patients may feel their symptoms will resolve. Of patients diagnosed with rosacea, only one-half have heard of the condition prior to diagnosis,8 which can largely be attributed to lack of patient education on the signs and symptoms of rosacea, a concern that prompted the National Rosacea Society to designate the month of April as rosacea awareness month.5

With sales of antiredness facial care products growing 35% from 2002 to 2007, accounting for an increase of $300 million in revenue, patients also may be turning to over-the-counter products first.10 Men with rosacea tend to present with more severe symptoms such as rhinophyma, which may be due to their desire to wait until their symptoms reached more advanced stages of disease before seeking medical help.5

Diagnosis of Rosacea

After the patient decides that his/her symptoms are unusual, severe, or intolerable enough to seek treatment, the issues of access to dermatologic care and receiving the correct diagnosis come into play. Accessing dermatologic care can be difficult, as appointments may be hard to obtain, and even if the patient is able to get an appointment, it could be many weeks later.11 For some rosacea patients, the anxiety of waiting for their appointment prompts them to seek support and advice from online message boards (eg, http://www.rosacea-support.org). The long wait for appointments may be attributed to the increased demand for dermatologists for cosmetic procedures.12 Additionally, disparities according to insurance type can contribute to difficulties procuring an appointment. In one study, privately insured dermatology patients demonstrated a 91% acceptance rate and shorter wait times for appointments compared to publicly insured patients who were limited to a 29.8% acceptance rate and longer wait times.11 Many patients then are left to wait for an appointment with a dermatologist or instead turn to a primary care physician. Of patients diagnosed with rosacea in one study (N=2847), the majority of patients were seen by a dermatologist (79%), while the other patients were diagnosed by a family physician (14%) or other types of physicians such as internists and ophthalmologists (7%).6

The diagnosis of rosacea usually is not a major hurdle for dermatologists, but misdiagnoses can sometimes occur. The Rosacea Research & Development Institute compiled multiple patient anecdotes describing the struggles of finally reaching the correct diagnosis of rosacea; however, no estimates as to the frequency of misdiagnoses was estimated.13 Even with an accurate diagnosis of rosacea, correct classification of the 4 types of rosacea (ie, erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, ocular) is necessary to avoid incorrect treatment recommendations. For example, patients with flushing often cannot tolerate topical medications in contrast to patients with the papulopustular subtype who benefit from them.14 In the meantime, the patients who are misdiagnosed may be met with frustration, as treatment was either delayed or incorrectly prescribed.

Although there are limited data regarding patient reactions after receiving a diagnosis of rosacea, it can be assumed that patients would be hopeful that diagnosis would lead to correct treatment. In a 2008 article in The New York Times, a rosacea patient was described as feeling relieved to be diagnosed with rosacea because it was an explanation for the development of pimples on the cheeks in her late 40s.10

Implementation of a Treatment Plan

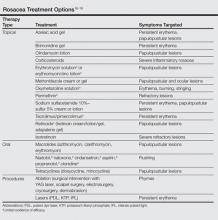

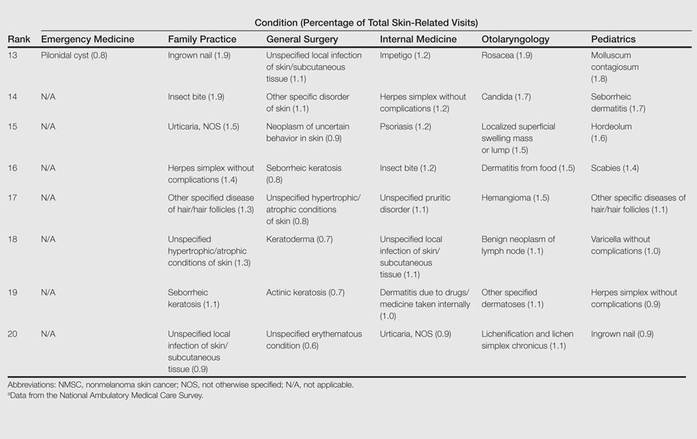

After recognizing the symptoms and receiving a correct diagnosis, the next step in the patient journey is treatment. Long-term management of incurable conditions such as rosacea is difficult. The main goals of treatment are to relieve symptoms, improve appearance, delay progression to advanced stages, and maintain remission.15 There are only a few reliable clinical trials regarding therapies for rosacea, so treatment has mostly relied on clinical experience (Table). The efficacy and safety of many older treatments has not been assessed.15 Mainstays of treatment include both topical agents and oral medications. The use of topical metronidazole, oral tetracycline, and oral isotretinoin have been found to improve both skin lesions and quality of life.18 Initially, a combination of a topical and an oral medication may be used for at least the first 12 weeks, and improvement is usually gradual, taking many weeks to become evident.15 Long-term treatment with topical medications often is required for maintenance, which can last another 6 months or more.19,20

Besides using pharmacologic therapies, some patients also may choose to undergo various procedures. The most common procedure is laser therapy, followed by dermabrasion, chemical peels, hot loop electrocoagulation, and surgical sculpting or plastic surgery.6 The use of these adjunct therapies may suggest impatience from the patient for improvement; it also indicates the lengths patients will go to and willingness to pay for improvement of symptoms.

Along with medication, patients are recommended to make changes to their skin care regimen and lifestyle. Rosacea patients typically have sensitive skin that may include symptoms such as dryness, scaling, stinging, burning, and pruritus.16 Skin care recommendations for rosacea patients include using a gentle cleanser and regularly applying sunscreen.5 Issues with physical appearance can be addressed with the use of cosmetic products such as green-tinted makeup to conceal skin lesions.21 Remission can be maintained by identifying certain triggers (eg, red wine, spicy foods, extreme temperatures, prolonged sun exposure, vigorous exercise) that can cause flare-ups.15 The most common trigger is sun exposure, making photoprotection an important component of the rosacea patient’s skin care regimen.6

Adherence

With a diagnosis and treatment plan in effect, the patient journey reaches the stage of treatment adherence, which should include ongoing education about the condition. Self-reported statistics from rosacea patients indicated that 28% of patients took time off from their treatment regimen,6 but actual nonadherence rates likely are higher. The most commonly reported reason for poor treatment adherence among rosacea patients was the impression that the symptoms had resolved or were adequately controlled.6 Treatment also must be affordable. In a national survey of rosacea patients, 24% of 427 patients receiving pharmacologic therapy planned on switching medications because of cost, and 17% of 769 patients discontinued medications due to co-pay/insurance issues.6 Other reasons cited for discontinuation of treatment included patient perception that symptoms were not that serious, co-pay/insurance issues, ineffectiveness of the medication, and side effects.6 Adherence to topical medications is lower than oral medications due to the time and inconvenience required for application.22 For some patients, topical medications may be too messy, have a strange odor, or stain clothing.

It is promising that most rosacea patients have reported the intent to continue using pharmacologic agents because the medication prevented worsening of their symptoms.6 However, there are still patients who switch or discontinue therapies without physician direction. These patients often cite that they desire more information at the time of diagnosis, particularly related to causes of flare-ups, physical symptoms to expect, drug treatment options, makeup to cover up visible symptoms, surgical or laser treatment options, psychological symptoms, patient support groups, and counseling options.6

Management

The last part of the journey is disease management, which occurs when the patient learns how to control his/her symptoms long-term. Important factors contributing to long-term control of rosacea flares are medication adherence and avoiding lifestyle triggers.23,24 Through the other stages of the journey, the patient has learned which treatments work and which factors may lead to exacerbation of symptoms.

Educating Patients on the Journey

The patient journey is a concept that can be applied to any disease state and brings to light roadblocks that patients may face from the initial diagnosis to successful disease management. Rosacea patients are faced with confusing and aggravating symptoms that can cause anxiety and may lead them to seek treatment from a physician. Facial flushing and phymatous changes of the nose can be mistaken for alcohol abuse, leading rosacea to be a socially stigmatizing disease.15 Because rosacea involves mostly the facial skin, it can disrupt social and professional interactions, leading to quality-of-life effects such as difficulty functioning on a day-to-day basis, which can be detrimental because patients usually are aged 30 to 50 years and may be perceived based on their appearance in the workforce.3 A lack of confidence, low self-esteem, embarrassment, and anxiety can even lead to serious psychiatric conditions such as depression and body dysmorphic disorder.25 Because the severity of rosacea increases over time, it is important to educate patients about seeking early treatment; therefore, understanding and awareness of rosacea symptoms are necessary to prompt patients to see a medical professional to either confirm or refute the diagnosis.

Rosacea is a clinical diagnosis that relies on patterns of primary and secondary features, as outlined in a 2002 report by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea.5 Even with this consensus grading system, it appears that additional fine-tuning of the criteria is needed in the disease definition. Importantly, because much of the pathogenesis and progression of rosacea is still not completely understood, there is no laboratory benchmark test that can be utilized for correct diagnosis.14 Moreover, many of the clinical manifestations of rosacea are shared with other conditions, and patients may present with different symptoms or varying combinations.26

Treatment of rosacea is multifactorial and behavioral, as patients must not only be able to obtain and adhere to oral and topical regimens and possible procedures but also avoid various lifestyle and environmental triggers and learn to cope with emotional distress caused by their symptoms. Although patients who discontinue use of medications appear to be in the minority, education is still needed to stress the chronic nature of rosacea and the importance of the continuation of treatment. Collaboration between the physician and patient is needed to determine why a certain medication may not be effective and explore other treatment options. Treatment ineffectiveness could be due to incorrect use of the product, failure to use an adjunct skin care regimen, or inability to control rosacea triggers. Adequate early follow-up also is needed to maximize patient adherence to treatment.27 Working together with the patient to develop a treatment plan that can be followed is necessary for long-term control of rosacea symptoms.

There is little information on how to address the psychological needs of patients, but patients can find support from various avenues. For instance, the National Rosacea Society, a large advocacy group, produces newsletters and educational materials for both physicians and patients.28,29 There also are online support groups for rosacea patients that have thousands of members who exchange stories and provide words of encouragement. Although there are not many face-to-face support groups, physicians may consider developing live support groups for their rosacea patients. As patients achieve the later stages of the rosacea patient journey, they hopefully will have controlled their symptoms by following a treatment regimen and learning to adapt to a new life of successful disease management.

Many aspects of the rosacea patient journey have yet to be explored. It is uncertain how long patients with symptoms of rosacea wait before seeking treatment, what methods they use to control their rosacea before they receive a prescribed treatment or physician recommendations, and how they react to their diagnosis. It also is unknown how many rosacea patients receive an initial misdiagnosis of another condition and which physicians typically make the misdiagnosis. We also need to know more about the role of psychological issues in addressing patient adherence to treatment. Similarly, what role do support groups such as online forums play on adherence? There is a need for more patient education and awareness of rosacea.

Conclusion

Patients may be relieved that rosacea is not a life-threatening condition, but they may be disappointed that there is no cure for rosacea. As the patient and dermatologist work together to find an appropriate treatment plan, identify certain triggers, and modify the skin care routine, the patient can become disciplined in controlling rosacea symptoms. Ultimately, with the alleviation of visible symptoms, the patient’s quality of life also can improve. Better understanding of the rosacea patient perspective can lead to a more efficient health care system, improved patient care, and better patient satisfaction.

1. Baldwin HE. Systemic therapy for rosacea. Skin Therapy Lett. 2007;12:1-5, 9.

2. Drake L. Rosacea now estimated to affect at least 16 million Americans. Rosacea Review. Winter 2010. http://www.rosacea.org/rr/2010/winter/article_1.php. Accessed December 11, 2014.

3. Rosacea as an inflammatory disease: an expert interview with Brian Berman, MD, PhD. Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/722156. Published May 27, 2010. Accessed December 11, 2014.

4. HealthEd Group, Inc. Rheumatoid arthritis patient journey map. http://visual.ly/rheumatoid-arthritis-patient-journey-map. Accessed December 19, 2014.

5. Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

6. Elewski BE. Results of a national rosacea patient survey: common issues that concern rosacea sufferers. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:120-123.

7. Del Rosso J. Management of rosacea in the United States: analysis based on recent prescribing patterns and insurance claims. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:AB13.

8. New survey reveals first impressions may not always be rosy for people with the widespread skin condition rosacea. Medical News Today Web site. http://www.medicalnew today.com/releases/185491.php. Updated April 15, 2010. Accessed December 12, 2014.

9. Shear NH, Levine C. Needs survey of Canadian rosacea patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:178-181.

10. Sweeney C. In a perfect world, rosacea remains a problem. New York Times. April 24, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/24/fashion/24SKIN.html?pagewanted=all. Accessed December 12, 2014.

11. Alghothani L, Jacks SK, Vander HA, et al. Disparities in access to dermatologic care according to insurance type. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:956-957.

12. Resneck J Jr. Too few or too many dermatologists? difficulties in assessing optimal workforce size. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1295-1301.

13. Rosacea Research & Development Institute Web site. http://irosacea.org/misdiagnosed_rosacea.html. Accessed December 19, 2014.

14. Crawford GH, Pelle MT, James WD. Rosacea: I. etiology, pathogenesis, and subtype classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:327-341.

15. Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dreno B, et al. Rosacea—global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:188-200.

16. Del Rosso JQ, Baldwin H, Webster G. American Acne & Rosacea Society rosacea medical management guidelines. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:531-533.

17. Fowler J Jr, Jackson M, Moore A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, and vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:650-656.

18. Aksoy B, Altaykan-Hapa A, Egemen D, et al. The impact of rosacea on quality of life: effects of demographic and clinical characteristics and various treatment modalities. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:719-725.

19. Dahl MV, Katz HI, Krueger GG, et al. Topical metronidazole maintains remissions of rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:679-683.

20. Thiboutot DM, Fleischer AB, Del Rosso JQ, et al. A multicenter study of topical azelaic acid 15% gel in combination with oral doxycycline as initial therapy and azelaic acid 15% gel as maintenance monotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:639-648.

21. Boehncke WH, Ochsendorf F, Paeslack I, et al. Decorative cosmetics improve the quality of life in patients with disfiguring skin diseases. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:577-580.

22. Jackson JM, Pelle M. Topical rosacea therapy: the importance of vehicles for efficacy, tolerability and compliance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:627-633.

23. Wolf JE Jr. Medication adherence: a key factor in effective management of rosacea. Adv Ther. 2001;18:272-281.

24. Managing rosacea. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/patients/materials/managing/lifestyle.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

25. van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Lack of ‘appropriately assessed’ patient-reported outcomes in randomized controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of interventions for rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:442-444.

26. Del Rosso JQ. Advances in understanding and managing rosacea: part 2: the central role, evaluation, and medical management of diffuse and persistent facial erythema of rosacea. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:26-36.

27. Davis SA, Lin HC, Yu CH, et al. Underuse of early follow-up visits: a missed opportunity to improve patients’ adherence. 2014;13:833-836.

28. If you have rosacea, you’re not alone. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/patients/index.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

29. Tools for the professional. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/physicians/index.php. Accessed December 19, 2014.

Rosacea patients experience symptoms ranging from flushing to persistent acnelike rashes that can cause low self-esteem and anxiety, leading to social and professional isolation.1 Although it is estimated that 16 million individuals in the United States have rosacea, only 10% seek treatment.2,3 The motivation for patients to seek and adhere to treatment is not well characterized.

A patient journey is a map of the steps a patient takes as he/she progresses through different segments of the disease from diagnosis to management, including all the influences that can push him/her toward or away from certain decisions. The patient journey model provides a structure for understanding key issues in rosacea management, including barriers to successful treatment outcomes.

The patient journey model progresses from development of disease and diagnosis to treatment and disease management (Figure). We sought to examine each step of the rosacea patient journey to better understand key patient care boundaries faced by rosacea patients. We assessed the current literature regarding each step of the patient experience and identified areas of the patient journey with limited research.

Click here to view the figure as a PDF to print for future reference.

Researching the Patient Experience

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a search of the National Rosacea Society Web site (http://www.rosacea.org) were conducted to identify articles and materials that quantitatively or qualitatively described rosacea patient experiences. Search terms included rosacea, rosacea patient experience, rosacea treatment, rosacea adherence, and rosacea quality of life. A Google search also was conducted using the same terms to obtain current news articles online. Current literature pertaining to the patient journey was summarized.

To create a model for the rosacea patient journey, we refined a rheumatoid arthritis patient journey map4 and included the critical components of the journey for rosacea patients. We organized the journey into stages, including prediagnosis, diagnosis, treatment, adherence, and management. We first explored what occurs prior to diagnosis, which includes the patient’s symptoms before visiting a physician. We then examined the process of diagnosis and the implementation of a treatment plan. Treatment adherence was then explored, ending with the ways patients self-manage their disease beyond the physician’s office.

Prediagnosis: What Motivates Patients to Seek Treatment

Rosacea can present with many symptoms that may lead patients to see a physician, including facial erythema and telangiectases, papules and pustules, phymatous changes, and ocular manifestations.5 The most common concern is temporary facial flushing, followed by persistent redness, then bumps and pimples.6 Many patients seek treatment after persistent facial flushing and an intolerable burning sensation. Some middle-aged patients decide to see a dermatologist for the first time when they break out in acne lesions after a history of clear skin. Others seek treatment because they can no longer tolerate the pain and embarrassment associated with their symptoms. However, patients who seek treatment only account for a small proportion of patients with rosacea, as only 10% of patients seek conventional medical treatment.7 Furthermore, symptomatic patients on average wait 7 months to 5 years before receiving a diagnosis.8,9

Care often is delayed or not pursued because many rosacea symptoms are mild when they first appear and may not initially bother the patient. Patients may not think anything of their symptoms and dismiss them as either acne vulgaris or sunburn. Due to the relapsing and remitting nature of the disease course, patients may feel their symptoms will resolve. Of patients diagnosed with rosacea, only one-half have heard of the condition prior to diagnosis,8 which can largely be attributed to lack of patient education on the signs and symptoms of rosacea, a concern that prompted the National Rosacea Society to designate the month of April as rosacea awareness month.5

With sales of antiredness facial care products growing 35% from 2002 to 2007, accounting for an increase of $300 million in revenue, patients also may be turning to over-the-counter products first.10 Men with rosacea tend to present with more severe symptoms such as rhinophyma, which may be due to their desire to wait until their symptoms reached more advanced stages of disease before seeking medical help.5

Diagnosis of Rosacea