User login

Pruritic Rash on the Neck and Back

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

A comprehensive metabolic panel collected from our patient 1 month earlier did not reveal any abnormalities. Serum methylmalonic acid and homocysteine were both elevated at 417 nmol/L (reference range [for those aged 2–59 years], 55–335 nmol/L) and 23 μmol/L (reference range, 5–15 μmol/L), respectively. Serum folate and 25-hydroxyvitamin D were low at 3.1 ng/mL (reference range, >4.8 ng/mL) and 5 ng/mL (reference range, 30–80 ng/mL), respectively. Vitamin B12 was within reference range. Two 4-mm punch biopsies collected from the upper back showed spongiotic dermatitis.

Our patient’s histopathology results along with the rash distribution and medical history of anorexia increased suspicion for prurigo pigmentosa. A trial of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks was prescribed. At 2-week follow-up, the patient’s mother revealed a history of ketosis in her daughter, solidifying the diagnosis. The patient was counseled on maintaining a healthy diet to prevent future breakouts. The patient’s rash resolved with diet modification and doxycycline; however, it recurred upon relapse of anorexia 4 months later.

Prurigo pigmentosa, originally identified in Japan by Nagashima et al,1 is an uncommon recurrent inflammatory disorder predominantly observed in young adults of Asian descent. Subsequently, it was reported to occur among individuals from different ethnic backgrounds, indicating potential underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis in Western countries.2 Although a direct pathogenic cause for prurigo pigmentosa has not been identified, a strong association has been linked to diet, specifically when ketosis is induced, such as in ketogenic diets and anorexia nervosa.3-5 Other possible causes include sunlight exposure, clothing friction, and sweating.1,5 The disease course is characterized by intermittent flares and spontaneous resolution, with recurrence in most cases. During the active phase, intensely pruritic, papulovesicular or urticarial papules are predominant and most often are localized to the upper body and torso, including the back, shoulders, neck, and chest.5 These flares can persist for several days but eventually subside, leaving behind a characteristic reticular pigmentation that can persist for months.5 First-line treatment often involves the use of tetracycline antibiotics, such as minocycline or doxycycline. 2,4,5 Dapsone often is used with successful resolution. 6 Dietary modifications also have been found to be effective in treating prurigo pigmentosa, particularly in patients presenting with dietary insufficiency.6,7 Increased carbohydrate intake has been shown to promote resolution. 6 Topical corticosteroids demonstrate limited efficacy in controlling flares.6,8

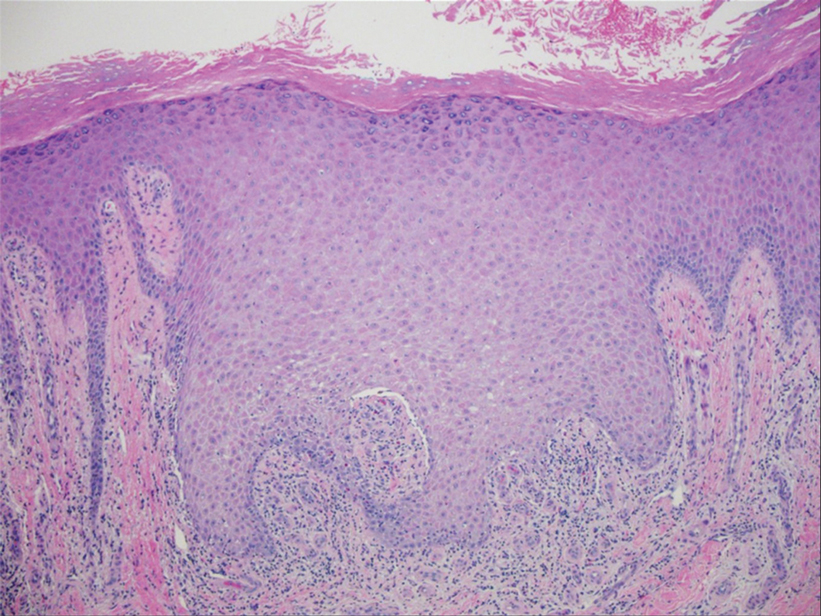

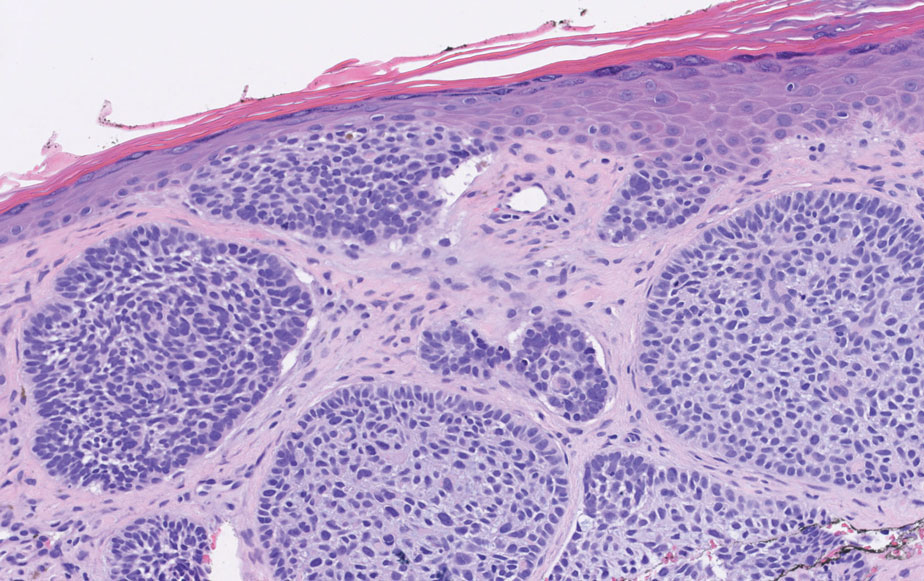

Histopathology has been variably described, with initial findings reported as nonspecific.1 However, it was later described as a distinct inflammatory disease of the skin with histologically distinct stages.2,9 Early stages reveal scattered dermal, dermal papillary, and perivascular neutrophilic infiltration.9 The lesions then progress and become fully developed, at which point neutrophilic infiltration becomes more prominent, accompanied by the presence of intraepidermal neutrophils and spongiosis. As the lesions resolve, the infiltration transitions to lymphocytic, and lichenoid changes can sometimes be appreciated along with epidermal hyperplasia, hyperpigmentation, and dermal melanophages.9 Although these findings aid in the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa, a clinicopathologic correlation is necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Because prurigo pigmentosa is rare, it often is misdiagnosed as another condition with a similar presentation and nonspecific biopsy findings.6 Allergic contact dermatitis is a common type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction that manifests similar to prurigo pigmentosa with pruritus and a well-demarcated distribution10 that is related to the pattern of allergen exposure; in the case of allergic contact dermatitis related to textiles, a well-demarcated rash will appear in the distribution area of the associated clothing (eg, shirt, pants, shorts).11 Development of allergy involves exposure and sensitization to an allergen, followed by subsequent re-exposure that results in cutaneous T-cell activation and inflammation. 10 Histopathology shows nonspecific spongiotic inflammation, and the gold standard for diagnosis is patch testing to identify the causative substance(s). Definitive treatment includes avoidance of identified allergies; however, if patients are unable to avoid the allergen or the cause is unknown, then corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or calcineurin inhibitors are beneficial in controlling symptoms and flares.10

Pityrosporum folliculitis (also known as Malassezia folliculitis) is a fungal acneform condition that arises from overgrowth of normal skin flora Malassezia yeast,12 which may be due to occlusion of follicles or disruption of the normal flora composition. Clinically, the manifestation may resemble prurigo pigmentosa in distribution and presence of intense pruritus. However, pustular lesions and involvement of the face can aid in differentiating Pityrosporum from prurigo pigmentosa, which can be confirmed via periodic acid–Schiff staining with numerous round yeasts within affected follicles. Oral antifungal therapy typically yields rapid improvement and resolution of symptoms.12

Urticaria and prurigo pigmentosa share similar clinical characteristics, with symptoms of intense pruritus and urticarial lesions on the trunk.2,13 Urticaria is an IgEmediated type I hypersensitivity reaction characterized by wheals (ie, edematous red or pink lesions of variable size and shape that typically resolve spontaneously within 24–48 hours).13 Notably, urticaria will improve and in some cases completely resolve with antihistamines or anti-IgE antibody treatment, which may aid in distinguishing it from prurigo pigmentosa, as the latter typically exhibits limited response to such treatment.2 Histopathology also can assist in the diagnosis by ruling out other causes of similar rash; however, biopsies are not routinely done unless other inflammatory conditions are of high suspicion.13

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune, subepidermal, blistering dermatosis that is most common among the elderly.14 It is characterized by the presence of IgG antibodies that target BP180 and BP230, which initiate inflammatory cascades that lead to tissue damage and blister formation. It typically manifests as pruritic blistering eruptions, primarily on the limbs and trunk, but may involve the head, neck, or palmoplantar regions.14 Although blistering eruptions are the prodrome of the disease, some cases may present with nonspecific urticarial or eczematous lesions14,15 that may resemble prurigo pigmentosa. The diagnosis is confirmed through direct immunofluorescence microscopy of biopsied lesions, which reveals IgG and/or C3 deposits along the dermoepidermal junction.14 Management of bullous pemphigoid involves timely initiation of dapsone or systemic corticosteroids, which have demonstrated high efficacy in controlling the disease and its associated symptoms.15

Our patient achieved a favorable response to diet modification and doxycycline therapy consistent with the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa. Unfortunately, the condition recurred following a relapse of anorexia. Management of prurigo pigmentosa necessitates not only accurate diagnosis but also addressing any underlying factors that may contribute to disease exacerbation. We anticipate the eating disorder will pose a major challenge in achieving long-term control of prurigo pigmentosa.

- Nagashima M, Ohshiro A, Shimizu N. A peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation. Jpn J Dermatol. 1971;81:38-39.

- Boer A, Asgari M. Prurigo pigmentosa: an underdiagnosed disease? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:405-409. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.29334

- Michaels JD, Hoss E, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa after a strict ketogenic diet. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;32:248-251. doi:10.1111/pde.12275

- Teraki Y, Teraki E, Kawashima M, et al. Ketosis is involved in the origin of prurigo pigmentosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:509-511. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90460-0

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.003

- Wong M, Lee E, Wu Y, et al. Treatment of prurigo pigmentosa with diet modification: a medical case study. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2018;77:114-117.

- Almaani N, Al-Tarawneh AH, Msallam H. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathological report of three Middle Eastern patients. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018;2018:9406797. doi:10.1155/2018/9406797

- Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01640.x

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Lazarov A, Cordoba M, Plosk N, et al. Atypical and unusual clinical manifestations of contact dermatitis to clothing (textile contact dermatitis)—case presentation and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9. doi:10.5070/d30kd1d259

- Rubenstein RM, Malerich SA. Malassezia (Pityrosporum) folliculitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:37-41.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.036

- della Torre R, Combescure C, Cortés B, et al. Clinical presentation and diagnostic delay in bullous pemphigoid: a prospective nationwide cohort. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1111-1117. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11108.x

- Alonso-Llamazares J, Rogers RS 3rd, Oursler JR, et al. Bullous pemphigoid presenting as generalized pruritus: observations in six patients. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:508-514.

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

A comprehensive metabolic panel collected from our patient 1 month earlier did not reveal any abnormalities. Serum methylmalonic acid and homocysteine were both elevated at 417 nmol/L (reference range [for those aged 2–59 years], 55–335 nmol/L) and 23 μmol/L (reference range, 5–15 μmol/L), respectively. Serum folate and 25-hydroxyvitamin D were low at 3.1 ng/mL (reference range, >4.8 ng/mL) and 5 ng/mL (reference range, 30–80 ng/mL), respectively. Vitamin B12 was within reference range. Two 4-mm punch biopsies collected from the upper back showed spongiotic dermatitis.

Our patient’s histopathology results along with the rash distribution and medical history of anorexia increased suspicion for prurigo pigmentosa. A trial of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks was prescribed. At 2-week follow-up, the patient’s mother revealed a history of ketosis in her daughter, solidifying the diagnosis. The patient was counseled on maintaining a healthy diet to prevent future breakouts. The patient’s rash resolved with diet modification and doxycycline; however, it recurred upon relapse of anorexia 4 months later.

Prurigo pigmentosa, originally identified in Japan by Nagashima et al,1 is an uncommon recurrent inflammatory disorder predominantly observed in young adults of Asian descent. Subsequently, it was reported to occur among individuals from different ethnic backgrounds, indicating potential underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis in Western countries.2 Although a direct pathogenic cause for prurigo pigmentosa has not been identified, a strong association has been linked to diet, specifically when ketosis is induced, such as in ketogenic diets and anorexia nervosa.3-5 Other possible causes include sunlight exposure, clothing friction, and sweating.1,5 The disease course is characterized by intermittent flares and spontaneous resolution, with recurrence in most cases. During the active phase, intensely pruritic, papulovesicular or urticarial papules are predominant and most often are localized to the upper body and torso, including the back, shoulders, neck, and chest.5 These flares can persist for several days but eventually subside, leaving behind a characteristic reticular pigmentation that can persist for months.5 First-line treatment often involves the use of tetracycline antibiotics, such as minocycline or doxycycline. 2,4,5 Dapsone often is used with successful resolution. 6 Dietary modifications also have been found to be effective in treating prurigo pigmentosa, particularly in patients presenting with dietary insufficiency.6,7 Increased carbohydrate intake has been shown to promote resolution. 6 Topical corticosteroids demonstrate limited efficacy in controlling flares.6,8

Histopathology has been variably described, with initial findings reported as nonspecific.1 However, it was later described as a distinct inflammatory disease of the skin with histologically distinct stages.2,9 Early stages reveal scattered dermal, dermal papillary, and perivascular neutrophilic infiltration.9 The lesions then progress and become fully developed, at which point neutrophilic infiltration becomes more prominent, accompanied by the presence of intraepidermal neutrophils and spongiosis. As the lesions resolve, the infiltration transitions to lymphocytic, and lichenoid changes can sometimes be appreciated along with epidermal hyperplasia, hyperpigmentation, and dermal melanophages.9 Although these findings aid in the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa, a clinicopathologic correlation is necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Because prurigo pigmentosa is rare, it often is misdiagnosed as another condition with a similar presentation and nonspecific biopsy findings.6 Allergic contact dermatitis is a common type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction that manifests similar to prurigo pigmentosa with pruritus and a well-demarcated distribution10 that is related to the pattern of allergen exposure; in the case of allergic contact dermatitis related to textiles, a well-demarcated rash will appear in the distribution area of the associated clothing (eg, shirt, pants, shorts).11 Development of allergy involves exposure and sensitization to an allergen, followed by subsequent re-exposure that results in cutaneous T-cell activation and inflammation. 10 Histopathology shows nonspecific spongiotic inflammation, and the gold standard for diagnosis is patch testing to identify the causative substance(s). Definitive treatment includes avoidance of identified allergies; however, if patients are unable to avoid the allergen or the cause is unknown, then corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or calcineurin inhibitors are beneficial in controlling symptoms and flares.10

Pityrosporum folliculitis (also known as Malassezia folliculitis) is a fungal acneform condition that arises from overgrowth of normal skin flora Malassezia yeast,12 which may be due to occlusion of follicles or disruption of the normal flora composition. Clinically, the manifestation may resemble prurigo pigmentosa in distribution and presence of intense pruritus. However, pustular lesions and involvement of the face can aid in differentiating Pityrosporum from prurigo pigmentosa, which can be confirmed via periodic acid–Schiff staining with numerous round yeasts within affected follicles. Oral antifungal therapy typically yields rapid improvement and resolution of symptoms.12

Urticaria and prurigo pigmentosa share similar clinical characteristics, with symptoms of intense pruritus and urticarial lesions on the trunk.2,13 Urticaria is an IgEmediated type I hypersensitivity reaction characterized by wheals (ie, edematous red or pink lesions of variable size and shape that typically resolve spontaneously within 24–48 hours).13 Notably, urticaria will improve and in some cases completely resolve with antihistamines or anti-IgE antibody treatment, which may aid in distinguishing it from prurigo pigmentosa, as the latter typically exhibits limited response to such treatment.2 Histopathology also can assist in the diagnosis by ruling out other causes of similar rash; however, biopsies are not routinely done unless other inflammatory conditions are of high suspicion.13

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune, subepidermal, blistering dermatosis that is most common among the elderly.14 It is characterized by the presence of IgG antibodies that target BP180 and BP230, which initiate inflammatory cascades that lead to tissue damage and blister formation. It typically manifests as pruritic blistering eruptions, primarily on the limbs and trunk, but may involve the head, neck, or palmoplantar regions.14 Although blistering eruptions are the prodrome of the disease, some cases may present with nonspecific urticarial or eczematous lesions14,15 that may resemble prurigo pigmentosa. The diagnosis is confirmed through direct immunofluorescence microscopy of biopsied lesions, which reveals IgG and/or C3 deposits along the dermoepidermal junction.14 Management of bullous pemphigoid involves timely initiation of dapsone or systemic corticosteroids, which have demonstrated high efficacy in controlling the disease and its associated symptoms.15

Our patient achieved a favorable response to diet modification and doxycycline therapy consistent with the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa. Unfortunately, the condition recurred following a relapse of anorexia. Management of prurigo pigmentosa necessitates not only accurate diagnosis but also addressing any underlying factors that may contribute to disease exacerbation. We anticipate the eating disorder will pose a major challenge in achieving long-term control of prurigo pigmentosa.

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

A comprehensive metabolic panel collected from our patient 1 month earlier did not reveal any abnormalities. Serum methylmalonic acid and homocysteine were both elevated at 417 nmol/L (reference range [for those aged 2–59 years], 55–335 nmol/L) and 23 μmol/L (reference range, 5–15 μmol/L), respectively. Serum folate and 25-hydroxyvitamin D were low at 3.1 ng/mL (reference range, >4.8 ng/mL) and 5 ng/mL (reference range, 30–80 ng/mL), respectively. Vitamin B12 was within reference range. Two 4-mm punch biopsies collected from the upper back showed spongiotic dermatitis.

Our patient’s histopathology results along with the rash distribution and medical history of anorexia increased suspicion for prurigo pigmentosa. A trial of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks was prescribed. At 2-week follow-up, the patient’s mother revealed a history of ketosis in her daughter, solidifying the diagnosis. The patient was counseled on maintaining a healthy diet to prevent future breakouts. The patient’s rash resolved with diet modification and doxycycline; however, it recurred upon relapse of anorexia 4 months later.

Prurigo pigmentosa, originally identified in Japan by Nagashima et al,1 is an uncommon recurrent inflammatory disorder predominantly observed in young adults of Asian descent. Subsequently, it was reported to occur among individuals from different ethnic backgrounds, indicating potential underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis in Western countries.2 Although a direct pathogenic cause for prurigo pigmentosa has not been identified, a strong association has been linked to diet, specifically when ketosis is induced, such as in ketogenic diets and anorexia nervosa.3-5 Other possible causes include sunlight exposure, clothing friction, and sweating.1,5 The disease course is characterized by intermittent flares and spontaneous resolution, with recurrence in most cases. During the active phase, intensely pruritic, papulovesicular or urticarial papules are predominant and most often are localized to the upper body and torso, including the back, shoulders, neck, and chest.5 These flares can persist for several days but eventually subside, leaving behind a characteristic reticular pigmentation that can persist for months.5 First-line treatment often involves the use of tetracycline antibiotics, such as minocycline or doxycycline. 2,4,5 Dapsone often is used with successful resolution. 6 Dietary modifications also have been found to be effective in treating prurigo pigmentosa, particularly in patients presenting with dietary insufficiency.6,7 Increased carbohydrate intake has been shown to promote resolution. 6 Topical corticosteroids demonstrate limited efficacy in controlling flares.6,8

Histopathology has been variably described, with initial findings reported as nonspecific.1 However, it was later described as a distinct inflammatory disease of the skin with histologically distinct stages.2,9 Early stages reveal scattered dermal, dermal papillary, and perivascular neutrophilic infiltration.9 The lesions then progress and become fully developed, at which point neutrophilic infiltration becomes more prominent, accompanied by the presence of intraepidermal neutrophils and spongiosis. As the lesions resolve, the infiltration transitions to lymphocytic, and lichenoid changes can sometimes be appreciated along with epidermal hyperplasia, hyperpigmentation, and dermal melanophages.9 Although these findings aid in the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa, a clinicopathologic correlation is necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Because prurigo pigmentosa is rare, it often is misdiagnosed as another condition with a similar presentation and nonspecific biopsy findings.6 Allergic contact dermatitis is a common type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction that manifests similar to prurigo pigmentosa with pruritus and a well-demarcated distribution10 that is related to the pattern of allergen exposure; in the case of allergic contact dermatitis related to textiles, a well-demarcated rash will appear in the distribution area of the associated clothing (eg, shirt, pants, shorts).11 Development of allergy involves exposure and sensitization to an allergen, followed by subsequent re-exposure that results in cutaneous T-cell activation and inflammation. 10 Histopathology shows nonspecific spongiotic inflammation, and the gold standard for diagnosis is patch testing to identify the causative substance(s). Definitive treatment includes avoidance of identified allergies; however, if patients are unable to avoid the allergen or the cause is unknown, then corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or calcineurin inhibitors are beneficial in controlling symptoms and flares.10

Pityrosporum folliculitis (also known as Malassezia folliculitis) is a fungal acneform condition that arises from overgrowth of normal skin flora Malassezia yeast,12 which may be due to occlusion of follicles or disruption of the normal flora composition. Clinically, the manifestation may resemble prurigo pigmentosa in distribution and presence of intense pruritus. However, pustular lesions and involvement of the face can aid in differentiating Pityrosporum from prurigo pigmentosa, which can be confirmed via periodic acid–Schiff staining with numerous round yeasts within affected follicles. Oral antifungal therapy typically yields rapid improvement and resolution of symptoms.12

Urticaria and prurigo pigmentosa share similar clinical characteristics, with symptoms of intense pruritus and urticarial lesions on the trunk.2,13 Urticaria is an IgEmediated type I hypersensitivity reaction characterized by wheals (ie, edematous red or pink lesions of variable size and shape that typically resolve spontaneously within 24–48 hours).13 Notably, urticaria will improve and in some cases completely resolve with antihistamines or anti-IgE antibody treatment, which may aid in distinguishing it from prurigo pigmentosa, as the latter typically exhibits limited response to such treatment.2 Histopathology also can assist in the diagnosis by ruling out other causes of similar rash; however, biopsies are not routinely done unless other inflammatory conditions are of high suspicion.13

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune, subepidermal, blistering dermatosis that is most common among the elderly.14 It is characterized by the presence of IgG antibodies that target BP180 and BP230, which initiate inflammatory cascades that lead to tissue damage and blister formation. It typically manifests as pruritic blistering eruptions, primarily on the limbs and trunk, but may involve the head, neck, or palmoplantar regions.14 Although blistering eruptions are the prodrome of the disease, some cases may present with nonspecific urticarial or eczematous lesions14,15 that may resemble prurigo pigmentosa. The diagnosis is confirmed through direct immunofluorescence microscopy of biopsied lesions, which reveals IgG and/or C3 deposits along the dermoepidermal junction.14 Management of bullous pemphigoid involves timely initiation of dapsone or systemic corticosteroids, which have demonstrated high efficacy in controlling the disease and its associated symptoms.15

Our patient achieved a favorable response to diet modification and doxycycline therapy consistent with the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa. Unfortunately, the condition recurred following a relapse of anorexia. Management of prurigo pigmentosa necessitates not only accurate diagnosis but also addressing any underlying factors that may contribute to disease exacerbation. We anticipate the eating disorder will pose a major challenge in achieving long-term control of prurigo pigmentosa.

- Nagashima M, Ohshiro A, Shimizu N. A peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation. Jpn J Dermatol. 1971;81:38-39.

- Boer A, Asgari M. Prurigo pigmentosa: an underdiagnosed disease? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:405-409. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.29334

- Michaels JD, Hoss E, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa after a strict ketogenic diet. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;32:248-251. doi:10.1111/pde.12275

- Teraki Y, Teraki E, Kawashima M, et al. Ketosis is involved in the origin of prurigo pigmentosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:509-511. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90460-0

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.003

- Wong M, Lee E, Wu Y, et al. Treatment of prurigo pigmentosa with diet modification: a medical case study. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2018;77:114-117.

- Almaani N, Al-Tarawneh AH, Msallam H. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathological report of three Middle Eastern patients. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018;2018:9406797. doi:10.1155/2018/9406797

- Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01640.x

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Lazarov A, Cordoba M, Plosk N, et al. Atypical and unusual clinical manifestations of contact dermatitis to clothing (textile contact dermatitis)—case presentation and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9. doi:10.5070/d30kd1d259

- Rubenstein RM, Malerich SA. Malassezia (Pityrosporum) folliculitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:37-41.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.036

- della Torre R, Combescure C, Cortés B, et al. Clinical presentation and diagnostic delay in bullous pemphigoid: a prospective nationwide cohort. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1111-1117. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11108.x

- Alonso-Llamazares J, Rogers RS 3rd, Oursler JR, et al. Bullous pemphigoid presenting as generalized pruritus: observations in six patients. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:508-514.

- Nagashima M, Ohshiro A, Shimizu N. A peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation. Jpn J Dermatol. 1971;81:38-39.

- Boer A, Asgari M. Prurigo pigmentosa: an underdiagnosed disease? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:405-409. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.29334

- Michaels JD, Hoss E, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa after a strict ketogenic diet. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;32:248-251. doi:10.1111/pde.12275

- Teraki Y, Teraki E, Kawashima M, et al. Ketosis is involved in the origin of prurigo pigmentosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:509-511. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90460-0

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.003

- Wong M, Lee E, Wu Y, et al. Treatment of prurigo pigmentosa with diet modification: a medical case study. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2018;77:114-117.

- Almaani N, Al-Tarawneh AH, Msallam H. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathological report of three Middle Eastern patients. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018;2018:9406797. doi:10.1155/2018/9406797

- Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01640.x

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Lazarov A, Cordoba M, Plosk N, et al. Atypical and unusual clinical manifestations of contact dermatitis to clothing (textile contact dermatitis)—case presentation and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9. doi:10.5070/d30kd1d259

- Rubenstein RM, Malerich SA. Malassezia (Pityrosporum) folliculitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:37-41.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.036

- della Torre R, Combescure C, Cortés B, et al. Clinical presentation and diagnostic delay in bullous pemphigoid: a prospective nationwide cohort. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1111-1117. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11108.x

- Alonso-Llamazares J, Rogers RS 3rd, Oursler JR, et al. Bullous pemphigoid presenting as generalized pruritus: observations in six patients. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:508-514.

A 43-year-old woman presented with a pruritic rash across the neck and back of 6 months’ duration that progressively worsened. She had a medical history of anorexia nervosa, herpes zoster with a recent flare, and peripheral neuropathy. Physical examination showed numerous red scaly papules across the upper back and shoulders that coalesced in a reticular pattern. No similar papules were seen elsewhere on the body.

Lichenoid Dermatosis on the Feet

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lichen Planus

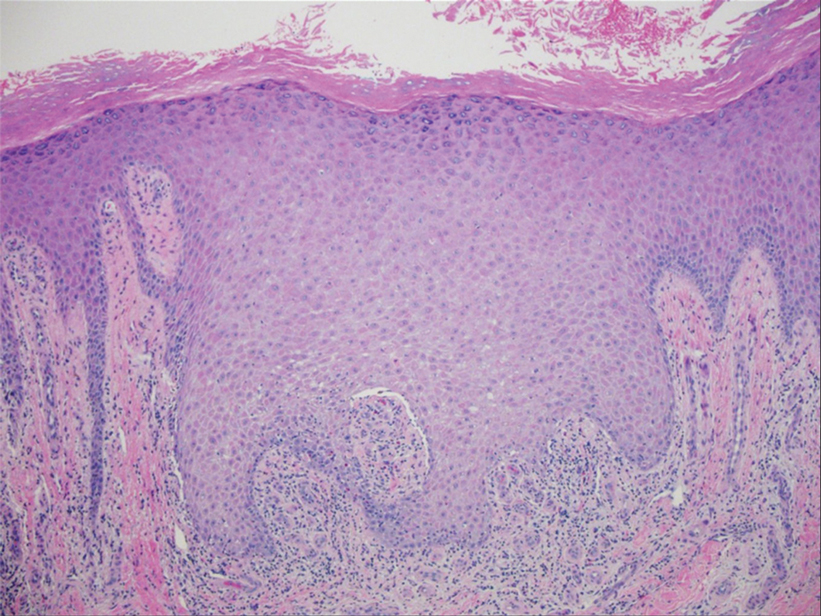

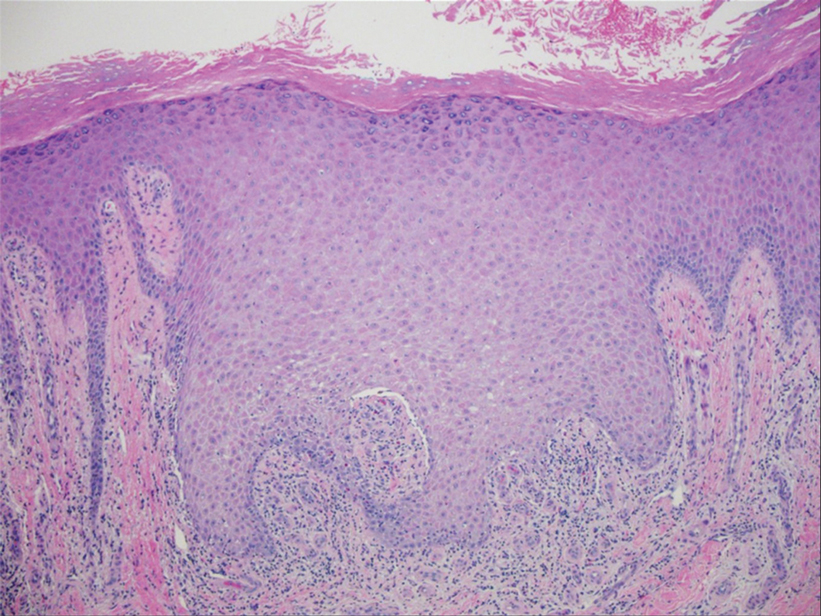

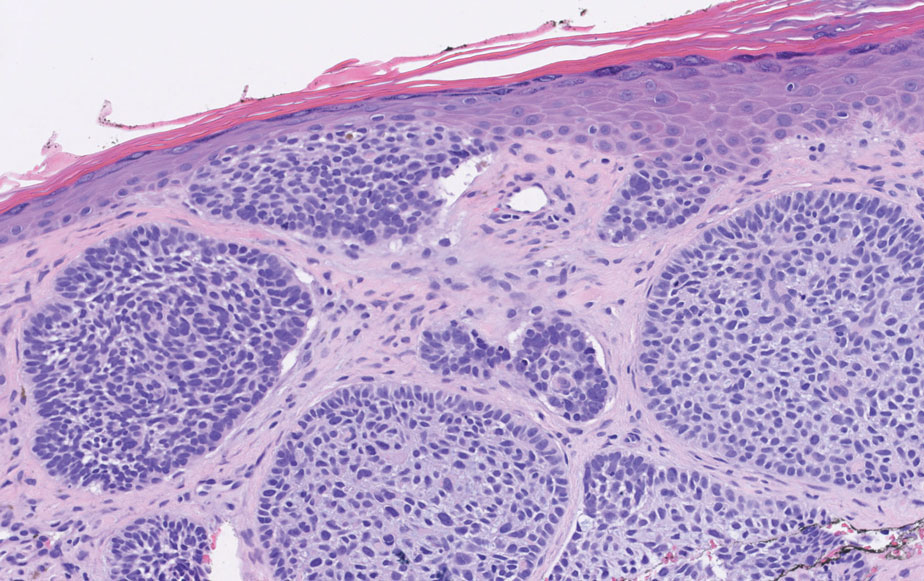

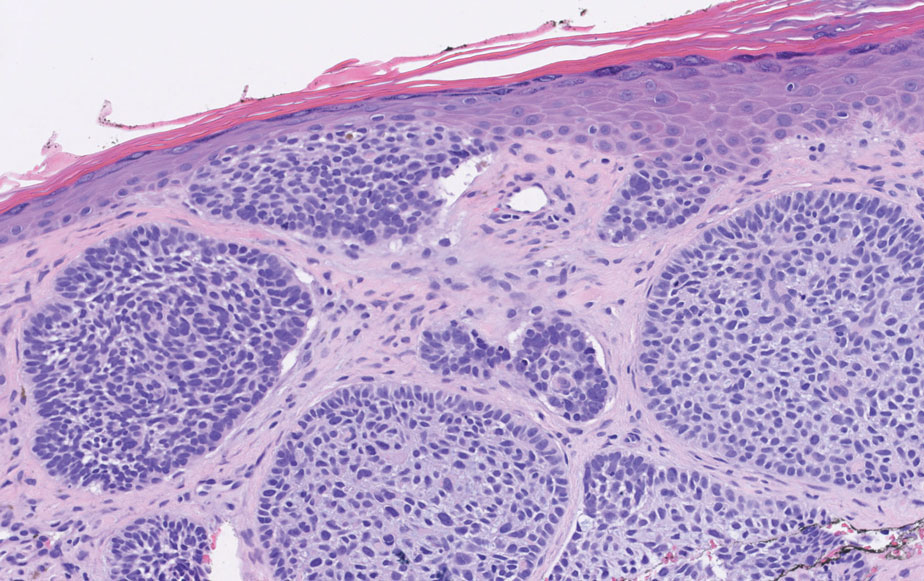

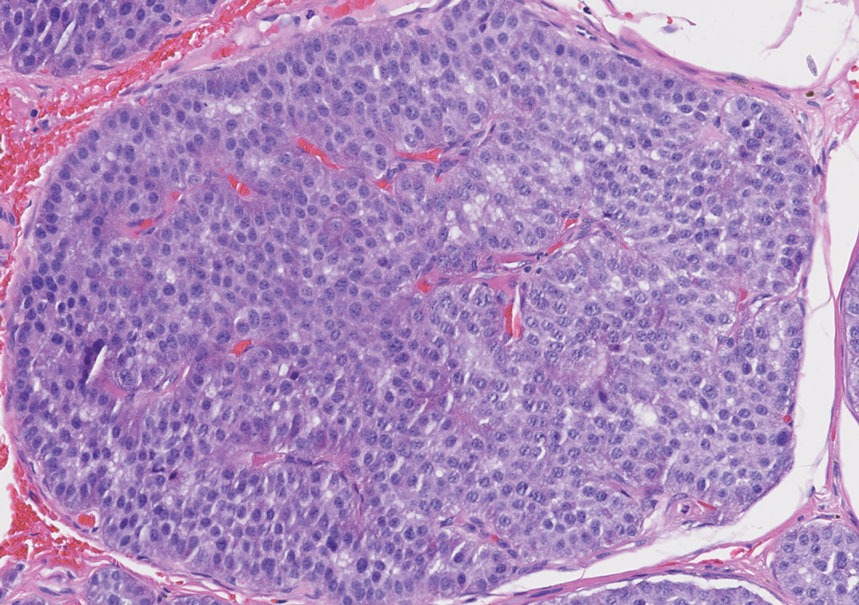

Two biopsies from the left lateral foot revealed hyperkeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, irregular acanthosis, and a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with a classic sawtooth pattern of the rete ridges (Figure 1). Based on the clinical findings and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with hypertrophic lichen planus (LP) and was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, which resulted in progression of the symptoms. She experienced notable improvement 3 months after adding methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly (Figure 2).

Lichen planus is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition of the skin and mucous membranes that classically manifests as pruritic violaceous papules and plaques, which commonly are found on the wrists, lower back, and ankles.1 The most common variants of LP are hypertrophic, linear, mucosal, actinic, follicular, pigmented, annular, atrophic, and guttate.2 The clinical presentation and biopsy results in our patient were consistent with the hypertrophic variant of LP, which is a chronic condition that most often manifests on the lower legs, especially around the ankles, as hyperkeratotic papules, plaques, and nodules.2,3 The exact pathophysiology of hypertrophic LP is unknown, but there is evidence that the immune system plays a role in its development and that the Koebner phenomenon may contribute to its exacerbation.4 There is a well-known association between LP and hepatitis. Patients with chronic LP may develop squamous cell carcinoma.4 The variants of LP can overlap and do not exist independent of one another. Recognizing the overlap in these variants allows for earlier diagnosis and therapeutic intervention of the disease process to limit disease progression and patient clinic visits and to improve patient quality of life.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic plaques of the feet and ankles can be broad and may include keratosis lichenoides chronica, palmoplantar keratoderma, palmoplantar psoriasis, or lichen amyloidosis. These conditions are classified based on various criteria that include extent of disease manifestations, morphology of palmoplantar skin involvement, inheritance patterns, and molecular pathogenesis.5 Keratosis lichenoides chronica is a rare dermatosis that presents as a distinctive seborrheic dermatitis–like facial eruption. The facial eruption is accompanied by violaceous papular and nodular lesions that appear on the extremities and trunk, typically arranged in a linear or reticular pattern.6 Palmoplantar keratoderma represents a group of acquired and hereditary conditions that are characterized by excessive thickening of the palms and soles.5 Palmoplantar psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that affects the palms and soles and can manifest as hyperkeratosis, pustular, or mixed morphology.7 Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis that manifests as multiple pruritic, firm, hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic papules on the shins that later coalesce in a rippled pattern.8,9

The first-line treatment for hypertrophic LP is topical corticosteroids. Alternative therapies include mycophenolate mofetil, acitretin, and intralesional corticosteroid injections.4 Treatment is similar for all of the LP variants.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Namazi MR, Bahmani M. Diagnosis: hypertrophic lichen planus. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:1-2. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.222

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:e3555. doi:10.7759 /cureus.3555

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2015.04.001

- Has C, Technau-Hafsi K. Palmoplantar keratodermas: clinical and genetic aspects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:123-139; quiz 140. doi:10.1111/ddg.12930

- Konstantinov KN, Søndergaard J, Izuno G, et al. Keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2 Pt 2):306-309. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(98)70570-5

- Miceli A, Schmieder GJ. Palmoplantar psoriasis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis—clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lichen Planus

Two biopsies from the left lateral foot revealed hyperkeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, irregular acanthosis, and a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with a classic sawtooth pattern of the rete ridges (Figure 1). Based on the clinical findings and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with hypertrophic lichen planus (LP) and was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, which resulted in progression of the symptoms. She experienced notable improvement 3 months after adding methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly (Figure 2).

Lichen planus is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition of the skin and mucous membranes that classically manifests as pruritic violaceous papules and plaques, which commonly are found on the wrists, lower back, and ankles.1 The most common variants of LP are hypertrophic, linear, mucosal, actinic, follicular, pigmented, annular, atrophic, and guttate.2 The clinical presentation and biopsy results in our patient were consistent with the hypertrophic variant of LP, which is a chronic condition that most often manifests on the lower legs, especially around the ankles, as hyperkeratotic papules, plaques, and nodules.2,3 The exact pathophysiology of hypertrophic LP is unknown, but there is evidence that the immune system plays a role in its development and that the Koebner phenomenon may contribute to its exacerbation.4 There is a well-known association between LP and hepatitis. Patients with chronic LP may develop squamous cell carcinoma.4 The variants of LP can overlap and do not exist independent of one another. Recognizing the overlap in these variants allows for earlier diagnosis and therapeutic intervention of the disease process to limit disease progression and patient clinic visits and to improve patient quality of life.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic plaques of the feet and ankles can be broad and may include keratosis lichenoides chronica, palmoplantar keratoderma, palmoplantar psoriasis, or lichen amyloidosis. These conditions are classified based on various criteria that include extent of disease manifestations, morphology of palmoplantar skin involvement, inheritance patterns, and molecular pathogenesis.5 Keratosis lichenoides chronica is a rare dermatosis that presents as a distinctive seborrheic dermatitis–like facial eruption. The facial eruption is accompanied by violaceous papular and nodular lesions that appear on the extremities and trunk, typically arranged in a linear or reticular pattern.6 Palmoplantar keratoderma represents a group of acquired and hereditary conditions that are characterized by excessive thickening of the palms and soles.5 Palmoplantar psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that affects the palms and soles and can manifest as hyperkeratosis, pustular, or mixed morphology.7 Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis that manifests as multiple pruritic, firm, hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic papules on the shins that later coalesce in a rippled pattern.8,9

The first-line treatment for hypertrophic LP is topical corticosteroids. Alternative therapies include mycophenolate mofetil, acitretin, and intralesional corticosteroid injections.4 Treatment is similar for all of the LP variants.

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lichen Planus

Two biopsies from the left lateral foot revealed hyperkeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, irregular acanthosis, and a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with a classic sawtooth pattern of the rete ridges (Figure 1). Based on the clinical findings and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with hypertrophic lichen planus (LP) and was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, which resulted in progression of the symptoms. She experienced notable improvement 3 months after adding methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly (Figure 2).

Lichen planus is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition of the skin and mucous membranes that classically manifests as pruritic violaceous papules and plaques, which commonly are found on the wrists, lower back, and ankles.1 The most common variants of LP are hypertrophic, linear, mucosal, actinic, follicular, pigmented, annular, atrophic, and guttate.2 The clinical presentation and biopsy results in our patient were consistent with the hypertrophic variant of LP, which is a chronic condition that most often manifests on the lower legs, especially around the ankles, as hyperkeratotic papules, plaques, and nodules.2,3 The exact pathophysiology of hypertrophic LP is unknown, but there is evidence that the immune system plays a role in its development and that the Koebner phenomenon may contribute to its exacerbation.4 There is a well-known association between LP and hepatitis. Patients with chronic LP may develop squamous cell carcinoma.4 The variants of LP can overlap and do not exist independent of one another. Recognizing the overlap in these variants allows for earlier diagnosis and therapeutic intervention of the disease process to limit disease progression and patient clinic visits and to improve patient quality of life.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic plaques of the feet and ankles can be broad and may include keratosis lichenoides chronica, palmoplantar keratoderma, palmoplantar psoriasis, or lichen amyloidosis. These conditions are classified based on various criteria that include extent of disease manifestations, morphology of palmoplantar skin involvement, inheritance patterns, and molecular pathogenesis.5 Keratosis lichenoides chronica is a rare dermatosis that presents as a distinctive seborrheic dermatitis–like facial eruption. The facial eruption is accompanied by violaceous papular and nodular lesions that appear on the extremities and trunk, typically arranged in a linear or reticular pattern.6 Palmoplantar keratoderma represents a group of acquired and hereditary conditions that are characterized by excessive thickening of the palms and soles.5 Palmoplantar psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that affects the palms and soles and can manifest as hyperkeratosis, pustular, or mixed morphology.7 Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis that manifests as multiple pruritic, firm, hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic papules on the shins that later coalesce in a rippled pattern.8,9

The first-line treatment for hypertrophic LP is topical corticosteroids. Alternative therapies include mycophenolate mofetil, acitretin, and intralesional corticosteroid injections.4 Treatment is similar for all of the LP variants.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Namazi MR, Bahmani M. Diagnosis: hypertrophic lichen planus. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:1-2. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.222

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:e3555. doi:10.7759 /cureus.3555

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2015.04.001

- Has C, Technau-Hafsi K. Palmoplantar keratodermas: clinical and genetic aspects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:123-139; quiz 140. doi:10.1111/ddg.12930

- Konstantinov KN, Søndergaard J, Izuno G, et al. Keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2 Pt 2):306-309. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(98)70570-5

- Miceli A, Schmieder GJ. Palmoplantar psoriasis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis—clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Namazi MR, Bahmani M. Diagnosis: hypertrophic lichen planus. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:1-2. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.222

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:e3555. doi:10.7759 /cureus.3555

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2015.04.001

- Has C, Technau-Hafsi K. Palmoplantar keratodermas: clinical and genetic aspects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:123-139; quiz 140. doi:10.1111/ddg.12930

- Konstantinov KN, Søndergaard J, Izuno G, et al. Keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2 Pt 2):306-309. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(98)70570-5

- Miceli A, Schmieder GJ. Palmoplantar psoriasis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis—clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

An 83-year-old woman presented for evaluation of hyperkeratotic plaques on the medial and lateral aspects of the left heel (top). Physical examination also revealed onychodystrophy of the toenails on the halluces (bottom). A crusted friable plaque on the lower lip and white plaques with peripheral reticulation and erosions on the buccal mucosa also were present. The patient had a history of nummular eczema, stasis dermatitis, and hand dermatitis. She denied a history of cold sores.

Firm Mobile Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Carcinoid Tumor

Carcinoid tumors are derived from neuroendocrine cell compartments and generally arise in the gastrointestinal tract, with a quarter of carcinoids arising in the small bowel.1 Carcinoid tumors have an incidence of approximately 2 to 5 per 100,000 patients.2 Metastasis of carcinoids is approximately 31.2% to 46.7%.1 Metastasis to the skin is uncommon; we present a rare case of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum with metastasis to the scalp.

Unlike our patient, most patients with carcinoid tumors have an indolent clinical course. The most common cutaneous symptom is flushing, which occurs in 75% of patients.3 Secreted vasoactive peptides such as serotonin may cause other symptoms such as tachycardia, diarrhea, and bronchospasm; together, these symptoms comprise carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid syndrome requires metastasis of the tumor to the liver or a site outside of the gastrointestinal tract because the liver will metabolize the secreted serotonin. However, even in patients with liver metastasis, carcinoid syndrome only occurs in approximately 10% of patients.4 Common skin findings of carcinoid syndrome include pellagralike dermatitis, flushing, and sclerodermalike changes.5 Our patient experienced several episodes of presyncope with symptoms of dyspnea, lightheadedness, and flushing but did not have bronchospasm or recurrent diarrhea. Intramuscular octreotide improved some symptoms.

The scalp accounts for approximately 15% of cutaneous metastases, the most common being from the lung, renal, and breast cancers.6 Cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors are rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms metastatic AND [carcinoid OR neuroendocrine] tumors AND [skin OR cutaneous] revealed 47 cases.7-11 Similar to other skin metastases, cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors commonly present as firm erythematous nodules of varying sizes that may be asymptomatic, tender, or pruritic (Figure 1). Cases of carcinoid tumors with cutaneous metastasis as the initial and only presenting sign are exceedingly rare.12

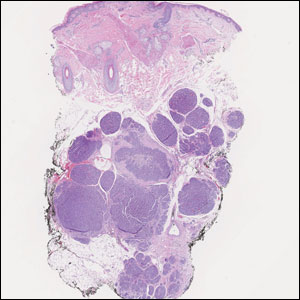

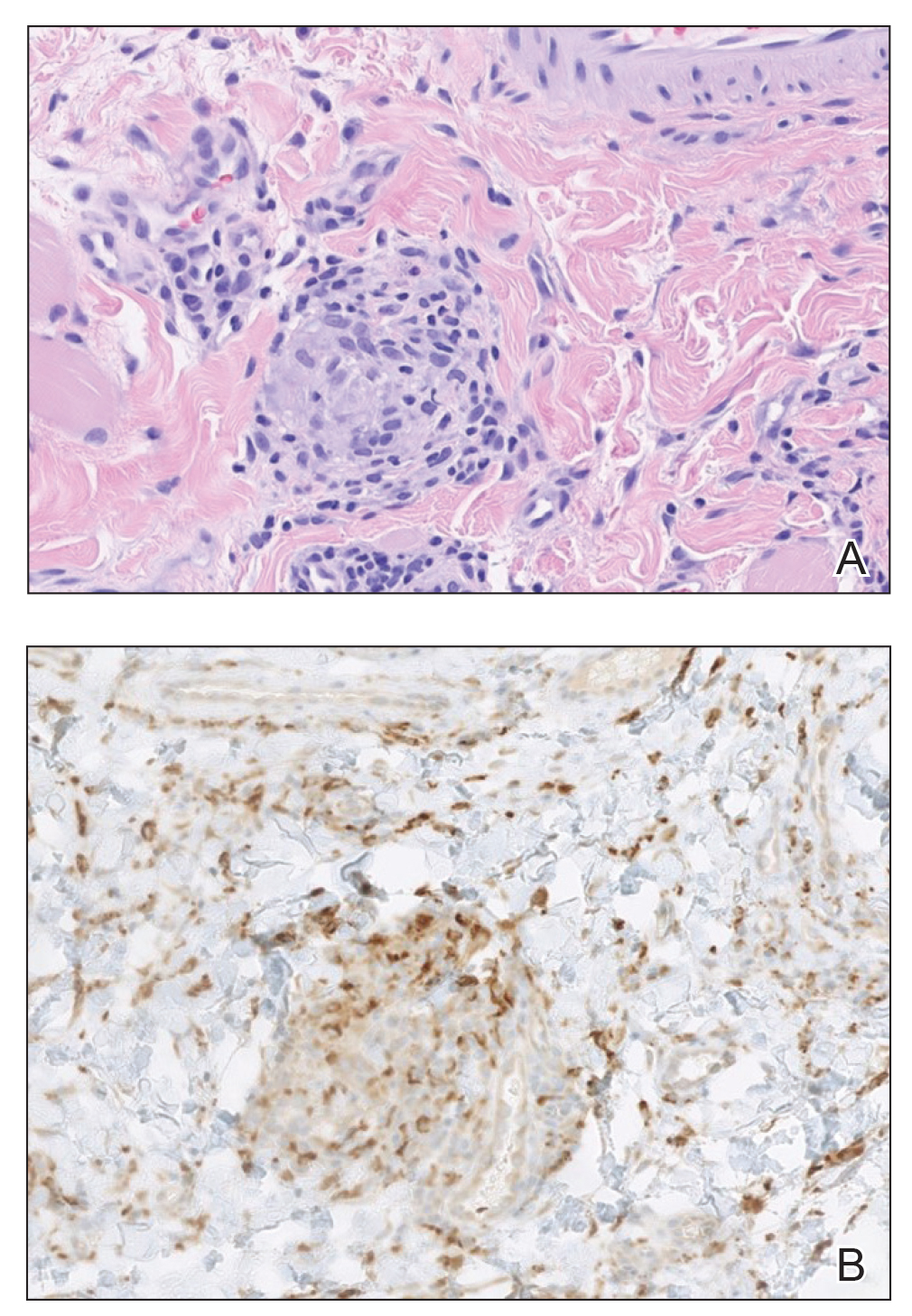

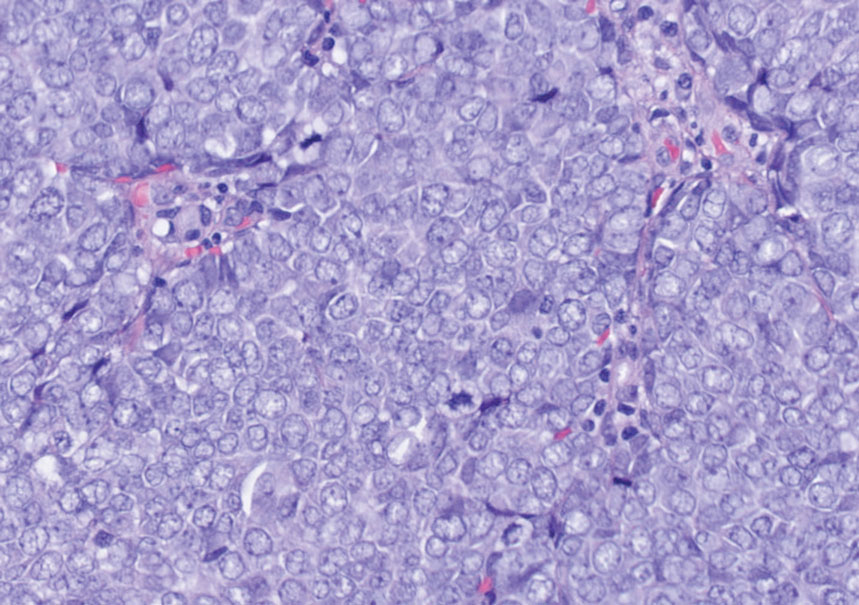

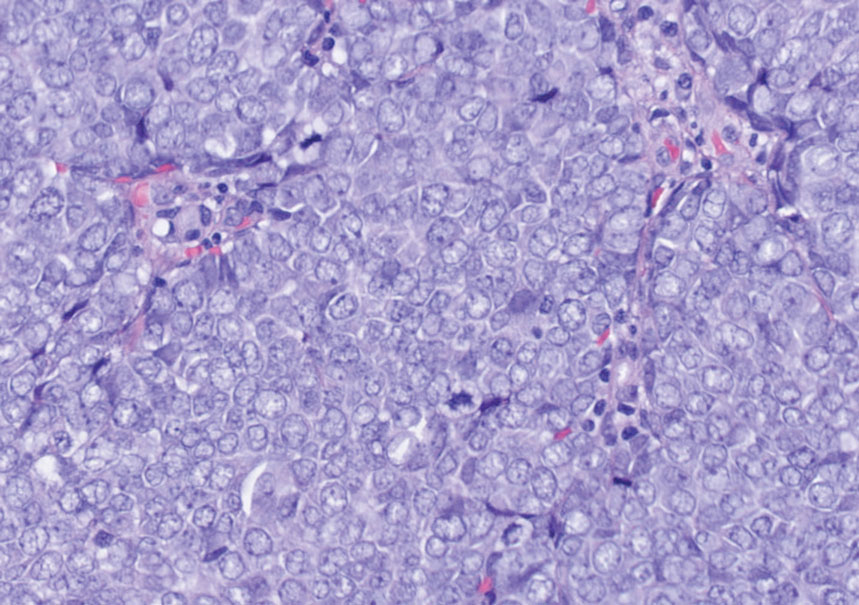

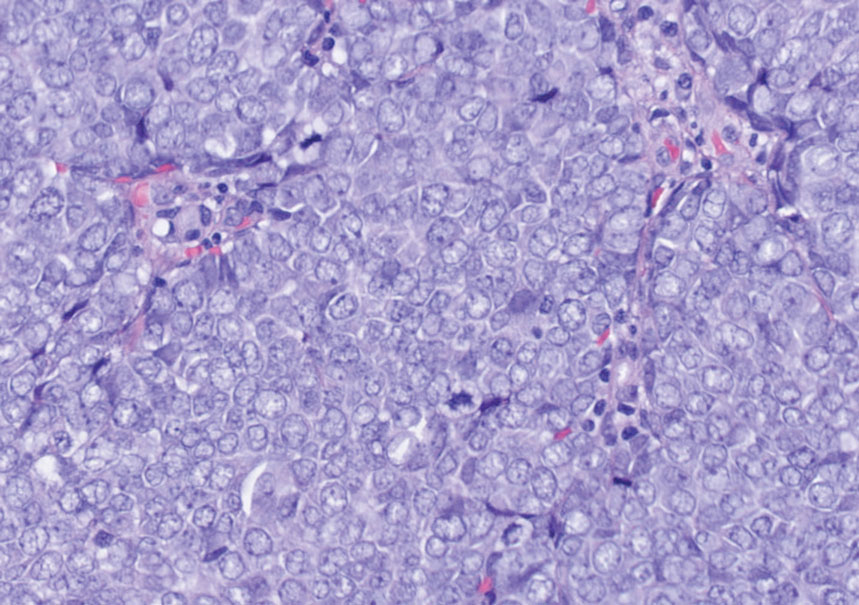

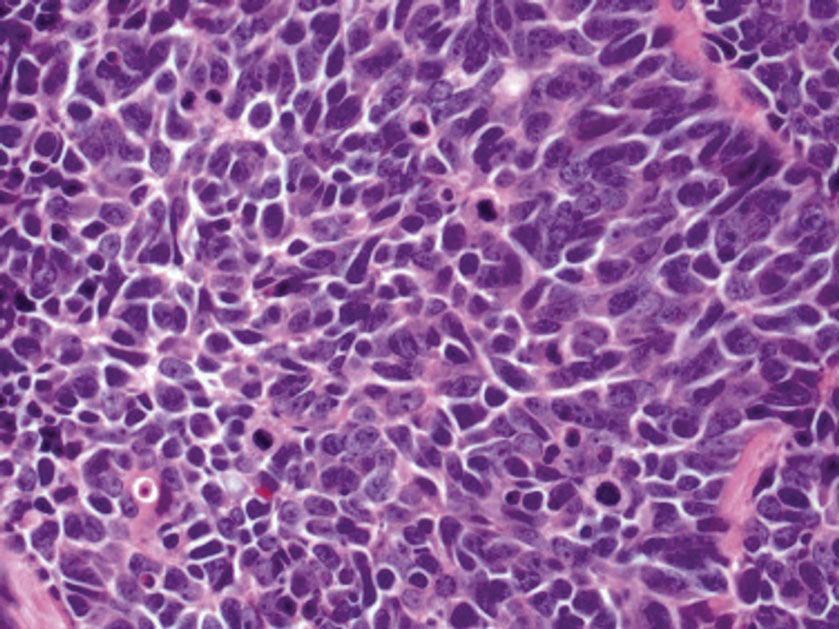

Histology of carcinoid tumors reveals a dermal neoplasm composed of loosely cohesive, mildly atypical, polygonal cells with salt-and-pepper chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm, which are similar findings to the primary tumor. The cells may grow in the typical trabecular or organoid neuroendocrine pattern or exhibit a pseudoglandular growth pattern with prominent vessels (quiz image, top).12 Positive chromogranin and synaptophysin immunostaining are the most common and reliable markers used for the diagnosis of carcinoid tumors.

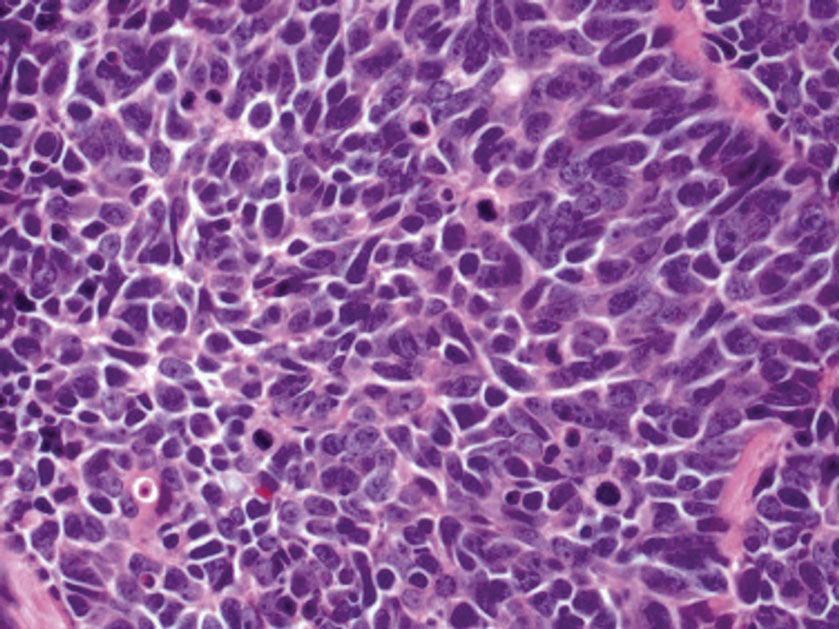

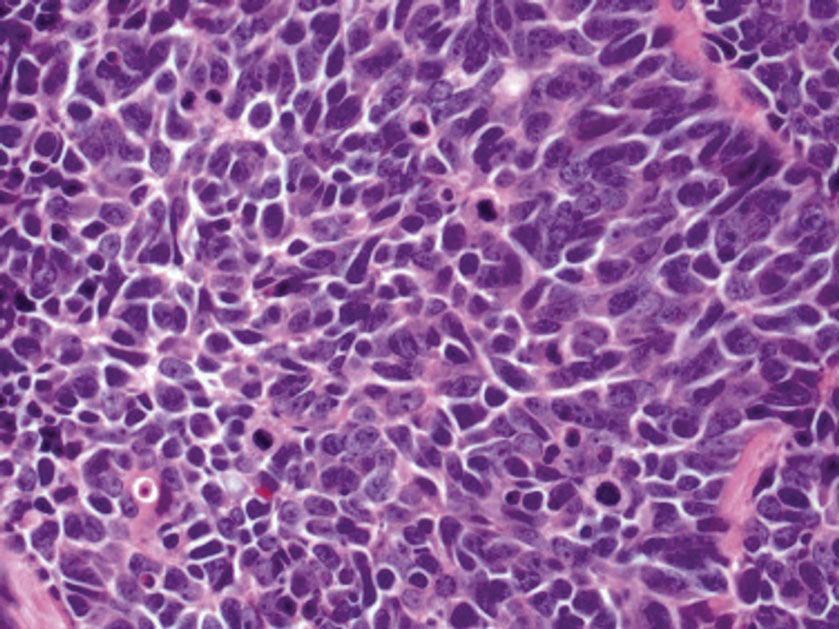

An important histopathologic differential diagnosis is the aggressive Merkel cell carcinoma, which also demonstrates homogenous salt-and-pepper chromatin but exhibits a higher mitotic rate and positive cytokeratin 20 staining (Figure 2).13 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) also may display similar features, including a blue tumor at scanning magnification and nodular or infiltrative growth patterns. The cell morphology of BCC is characterized by islands of basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm and frequent apoptosis, connecting to the epidermis with peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a myxoid stroma; BCC lacks the salt-and-pepper chromatin commonly seen in carcinoid tumors (Figure 3). Basal cell carcinoma is characterized by positive BerEP4 (epithelial cell adhesion molecule immunostain), cytokeratin 5/6, and cytokeratin 14 uptake. Cytokeratin 20, often used to diagnose Merkel cell carcinoma, is negative in BCC. Chromogranin and synaptophysin occasionally may be positive in BCC.14

The superficial Ewing sarcoma family of tumors also may be included in the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors of the skin, but they are very rare. These tumors possess strong positive membranous staining of cytokeratin 99 and also can stain positively for synaptophysin and chromogranin.15 Epithelial membrane antigen, which is negative in Ewing sarcomas, is positive in carcinoid tumors.16 Neuroendocrine tumors of all sites share similar basic morphologic patterns, and multiple primary tumors should be considered, including small cell lung carcinoma (Figure 4).17,18 Red granulations and true glandular lumina typically are not seen in the lungs but are common in gastrointestinal carcinoids.18 Regarding immunohistochemistry, TTF-1 is negative and CDX2 is positive in gastroenteropancreatic carcinoids, suggesting that these 2 markers can help distinguish carcinoids of unknown primary origin.19

Metastases in carcinoid tumors are common, with one study noting that the highest frequency of small intestinal metastases was from the ileal subset.20 At the time of diagnosis, 58% to 64% of patients with small intestine carcinoid tumors already had nonlocalized disease, with frequent sites being the lymph nodes (89.8%), liver (44.1%), lungs (13.6%), and peritoneum (13.6%). Regional and distant metastases are associated with substantially worse prognoses, with survival rates of 71.7% and 38.5%, respectively.1 Treatment of symptomatic unresectable disease focuses on symptomatic management with somatostatin analogs that also control tumor growth.21

We present a rare case of scalp metastasis of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum. Distant metastasis is associated with poorer prognosis and should be considered in patients with a known history of a carcinoid tumor.

Acknowledgment—We would like to acknowledge the Research Histology and Tissue Imaging Core at University of Illinois Chicago Research Resources Center for the immunohistochemistry studies.

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959.

- Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, et al. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1-18, vii.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Tomassetti P. Clinical aspects of carcinoid tumours. Italian J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31(suppl 2):S143-S146.

- Bell HK, Poston GJ, Vora J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:71-75.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2 pt 1):228-236.

- Garcia A, Mays S, Silapunt S. Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9052w9x1.

- Ciliberti MP, Carbonara R, Grillo A, et al. Unexpected response to palliative radiotherapy for subcutaneous metastases of an advanced small cell pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report of two different radiation schedules. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:311.

- Devnani B, Kumar R, Pathy S, et al. Cutaneous metastases from neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: an unusual metastatic lesion from an uncommon malignancy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018; 42:527-533.

- Falto-Aizpurua L, Seyfer S, Krishnan B, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor. Cutis. 2017;99:E13-E15.

- Dhingra R, Tse JY, Saif MW. Cutaneous metastasis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-Nets)[published online September 8, 2018]. JOP. 2018;19.

- Jedrych J, Busam K, Klimstra DS, et al. Cutaneous metastases as an initial manifestation of visceral well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor: a report of four cases and a review of literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:113-122.

- Lloyd RV. Practical markers used in the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2003;14:293-301.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Calabuig-Fariñas S, et al. Superficial Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors: a clinicopathological study with differential diagnoses. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:636-643.

- D’Cruze L, Dutta R, Rao S, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in the analysis of the spectrum of small round cell tumours at a tertiary care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1377-1382.

- Chirila DN, Turdeanu NA, Constantea NA, et al. Multiple malignant tumors. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2013;108:498-502.

- Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1628-1638.

- Lin X, Saad RS, Luckasevic TM, et al. Diagnostic value of CDX-2 and TTF-1 expressions in separating metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms of unknown origin. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:407-414.

- Olney JR, Urdaneta LF, Al-Jurf AS, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1985;51:37-41.

- Strosberg JR, Halfdanarson TR, Bellizzi AM, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and medical management of midgut neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2017;46:707-714.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Carcinoid Tumor

Carcinoid tumors are derived from neuroendocrine cell compartments and generally arise in the gastrointestinal tract, with a quarter of carcinoids arising in the small bowel.1 Carcinoid tumors have an incidence of approximately 2 to 5 per 100,000 patients.2 Metastasis of carcinoids is approximately 31.2% to 46.7%.1 Metastasis to the skin is uncommon; we present a rare case of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum with metastasis to the scalp.

Unlike our patient, most patients with carcinoid tumors have an indolent clinical course. The most common cutaneous symptom is flushing, which occurs in 75% of patients.3 Secreted vasoactive peptides such as serotonin may cause other symptoms such as tachycardia, diarrhea, and bronchospasm; together, these symptoms comprise carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid syndrome requires metastasis of the tumor to the liver or a site outside of the gastrointestinal tract because the liver will metabolize the secreted serotonin. However, even in patients with liver metastasis, carcinoid syndrome only occurs in approximately 10% of patients.4 Common skin findings of carcinoid syndrome include pellagralike dermatitis, flushing, and sclerodermalike changes.5 Our patient experienced several episodes of presyncope with symptoms of dyspnea, lightheadedness, and flushing but did not have bronchospasm or recurrent diarrhea. Intramuscular octreotide improved some symptoms.

The scalp accounts for approximately 15% of cutaneous metastases, the most common being from the lung, renal, and breast cancers.6 Cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors are rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms metastatic AND [carcinoid OR neuroendocrine] tumors AND [skin OR cutaneous] revealed 47 cases.7-11 Similar to other skin metastases, cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors commonly present as firm erythematous nodules of varying sizes that may be asymptomatic, tender, or pruritic (Figure 1). Cases of carcinoid tumors with cutaneous metastasis as the initial and only presenting sign are exceedingly rare.12

Histology of carcinoid tumors reveals a dermal neoplasm composed of loosely cohesive, mildly atypical, polygonal cells with salt-and-pepper chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm, which are similar findings to the primary tumor. The cells may grow in the typical trabecular or organoid neuroendocrine pattern or exhibit a pseudoglandular growth pattern with prominent vessels (quiz image, top).12 Positive chromogranin and synaptophysin immunostaining are the most common and reliable markers used for the diagnosis of carcinoid tumors.

An important histopathologic differential diagnosis is the aggressive Merkel cell carcinoma, which also demonstrates homogenous salt-and-pepper chromatin but exhibits a higher mitotic rate and positive cytokeratin 20 staining (Figure 2).13 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) also may display similar features, including a blue tumor at scanning magnification and nodular or infiltrative growth patterns. The cell morphology of BCC is characterized by islands of basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm and frequent apoptosis, connecting to the epidermis with peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a myxoid stroma; BCC lacks the salt-and-pepper chromatin commonly seen in carcinoid tumors (Figure 3). Basal cell carcinoma is characterized by positive BerEP4 (epithelial cell adhesion molecule immunostain), cytokeratin 5/6, and cytokeratin 14 uptake. Cytokeratin 20, often used to diagnose Merkel cell carcinoma, is negative in BCC. Chromogranin and synaptophysin occasionally may be positive in BCC.14

The superficial Ewing sarcoma family of tumors also may be included in the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors of the skin, but they are very rare. These tumors possess strong positive membranous staining of cytokeratin 99 and also can stain positively for synaptophysin and chromogranin.15 Epithelial membrane antigen, which is negative in Ewing sarcomas, is positive in carcinoid tumors.16 Neuroendocrine tumors of all sites share similar basic morphologic patterns, and multiple primary tumors should be considered, including small cell lung carcinoma (Figure 4).17,18 Red granulations and true glandular lumina typically are not seen in the lungs but are common in gastrointestinal carcinoids.18 Regarding immunohistochemistry, TTF-1 is negative and CDX2 is positive in gastroenteropancreatic carcinoids, suggesting that these 2 markers can help distinguish carcinoids of unknown primary origin.19

Metastases in carcinoid tumors are common, with one study noting that the highest frequency of small intestinal metastases was from the ileal subset.20 At the time of diagnosis, 58% to 64% of patients with small intestine carcinoid tumors already had nonlocalized disease, with frequent sites being the lymph nodes (89.8%), liver (44.1%), lungs (13.6%), and peritoneum (13.6%). Regional and distant metastases are associated with substantially worse prognoses, with survival rates of 71.7% and 38.5%, respectively.1 Treatment of symptomatic unresectable disease focuses on symptomatic management with somatostatin analogs that also control tumor growth.21

We present a rare case of scalp metastasis of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum. Distant metastasis is associated with poorer prognosis and should be considered in patients with a known history of a carcinoid tumor.

Acknowledgment—We would like to acknowledge the Research Histology and Tissue Imaging Core at University of Illinois Chicago Research Resources Center for the immunohistochemistry studies.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Carcinoid Tumor

Carcinoid tumors are derived from neuroendocrine cell compartments and generally arise in the gastrointestinal tract, with a quarter of carcinoids arising in the small bowel.1 Carcinoid tumors have an incidence of approximately 2 to 5 per 100,000 patients.2 Metastasis of carcinoids is approximately 31.2% to 46.7%.1 Metastasis to the skin is uncommon; we present a rare case of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum with metastasis to the scalp.

Unlike our patient, most patients with carcinoid tumors have an indolent clinical course. The most common cutaneous symptom is flushing, which occurs in 75% of patients.3 Secreted vasoactive peptides such as serotonin may cause other symptoms such as tachycardia, diarrhea, and bronchospasm; together, these symptoms comprise carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid syndrome requires metastasis of the tumor to the liver or a site outside of the gastrointestinal tract because the liver will metabolize the secreted serotonin. However, even in patients with liver metastasis, carcinoid syndrome only occurs in approximately 10% of patients.4 Common skin findings of carcinoid syndrome include pellagralike dermatitis, flushing, and sclerodermalike changes.5 Our patient experienced several episodes of presyncope with symptoms of dyspnea, lightheadedness, and flushing but did not have bronchospasm or recurrent diarrhea. Intramuscular octreotide improved some symptoms.

The scalp accounts for approximately 15% of cutaneous metastases, the most common being from the lung, renal, and breast cancers.6 Cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors are rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms metastatic AND [carcinoid OR neuroendocrine] tumors AND [skin OR cutaneous] revealed 47 cases.7-11 Similar to other skin metastases, cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors commonly present as firm erythematous nodules of varying sizes that may be asymptomatic, tender, or pruritic (Figure 1). Cases of carcinoid tumors with cutaneous metastasis as the initial and only presenting sign are exceedingly rare.12

Histology of carcinoid tumors reveals a dermal neoplasm composed of loosely cohesive, mildly atypical, polygonal cells with salt-and-pepper chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm, which are similar findings to the primary tumor. The cells may grow in the typical trabecular or organoid neuroendocrine pattern or exhibit a pseudoglandular growth pattern with prominent vessels (quiz image, top).12 Positive chromogranin and synaptophysin immunostaining are the most common and reliable markers used for the diagnosis of carcinoid tumors.

An important histopathologic differential diagnosis is the aggressive Merkel cell carcinoma, which also demonstrates homogenous salt-and-pepper chromatin but exhibits a higher mitotic rate and positive cytokeratin 20 staining (Figure 2).13 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) also may display similar features, including a blue tumor at scanning magnification and nodular or infiltrative growth patterns. The cell morphology of BCC is characterized by islands of basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm and frequent apoptosis, connecting to the epidermis with peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a myxoid stroma; BCC lacks the salt-and-pepper chromatin commonly seen in carcinoid tumors (Figure 3). Basal cell carcinoma is characterized by positive BerEP4 (epithelial cell adhesion molecule immunostain), cytokeratin 5/6, and cytokeratin 14 uptake. Cytokeratin 20, often used to diagnose Merkel cell carcinoma, is negative in BCC. Chromogranin and synaptophysin occasionally may be positive in BCC.14

The superficial Ewing sarcoma family of tumors also may be included in the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors of the skin, but they are very rare. These tumors possess strong positive membranous staining of cytokeratin 99 and also can stain positively for synaptophysin and chromogranin.15 Epithelial membrane antigen, which is negative in Ewing sarcomas, is positive in carcinoid tumors.16 Neuroendocrine tumors of all sites share similar basic morphologic patterns, and multiple primary tumors should be considered, including small cell lung carcinoma (Figure 4).17,18 Red granulations and true glandular lumina typically are not seen in the lungs but are common in gastrointestinal carcinoids.18 Regarding immunohistochemistry, TTF-1 is negative and CDX2 is positive in gastroenteropancreatic carcinoids, suggesting that these 2 markers can help distinguish carcinoids of unknown primary origin.19

Metastases in carcinoid tumors are common, with one study noting that the highest frequency of small intestinal metastases was from the ileal subset.20 At the time of diagnosis, 58% to 64% of patients with small intestine carcinoid tumors already had nonlocalized disease, with frequent sites being the lymph nodes (89.8%), liver (44.1%), lungs (13.6%), and peritoneum (13.6%). Regional and distant metastases are associated with substantially worse prognoses, with survival rates of 71.7% and 38.5%, respectively.1 Treatment of symptomatic unresectable disease focuses on symptomatic management with somatostatin analogs that also control tumor growth.21

We present a rare case of scalp metastasis of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum. Distant metastasis is associated with poorer prognosis and should be considered in patients with a known history of a carcinoid tumor.

Acknowledgment—We would like to acknowledge the Research Histology and Tissue Imaging Core at University of Illinois Chicago Research Resources Center for the immunohistochemistry studies.

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959.

- Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, et al. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1-18, vii.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Tomassetti P. Clinical aspects of carcinoid tumours. Italian J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31(suppl 2):S143-S146.

- Bell HK, Poston GJ, Vora J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:71-75.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2 pt 1):228-236.

- Garcia A, Mays S, Silapunt S. Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9052w9x1.

- Ciliberti MP, Carbonara R, Grillo A, et al. Unexpected response to palliative radiotherapy for subcutaneous metastases of an advanced small cell pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report of two different radiation schedules. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:311.

- Devnani B, Kumar R, Pathy S, et al. Cutaneous metastases from neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: an unusual metastatic lesion from an uncommon malignancy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018; 42:527-533.

- Falto-Aizpurua L, Seyfer S, Krishnan B, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor. Cutis. 2017;99:E13-E15.

- Dhingra R, Tse JY, Saif MW. Cutaneous metastasis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-Nets)[published online September 8, 2018]. JOP. 2018;19.

- Jedrych J, Busam K, Klimstra DS, et al. Cutaneous metastases as an initial manifestation of visceral well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor: a report of four cases and a review of literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:113-122.

- Lloyd RV. Practical markers used in the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2003;14:293-301.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Calabuig-Fariñas S, et al. Superficial Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors: a clinicopathological study with differential diagnoses. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:636-643.

- D’Cruze L, Dutta R, Rao S, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in the analysis of the spectrum of small round cell tumours at a tertiary care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1377-1382.

- Chirila DN, Turdeanu NA, Constantea NA, et al. Multiple malignant tumors. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2013;108:498-502.

- Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1628-1638.

- Lin X, Saad RS, Luckasevic TM, et al. Diagnostic value of CDX-2 and TTF-1 expressions in separating metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms of unknown origin. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:407-414.

- Olney JR, Urdaneta LF, Al-Jurf AS, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1985;51:37-41.

- Strosberg JR, Halfdanarson TR, Bellizzi AM, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and medical management of midgut neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2017;46:707-714.

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959.

- Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, et al. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1-18, vii.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Tomassetti P. Clinical aspects of carcinoid tumours. Italian J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31(suppl 2):S143-S146.

- Bell HK, Poston GJ, Vora J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:71-75.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2 pt 1):228-236.

- Garcia A, Mays S, Silapunt S. Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9052w9x1.

- Ciliberti MP, Carbonara R, Grillo A, et al. Unexpected response to palliative radiotherapy for subcutaneous metastases of an advanced small cell pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report of two different radiation schedules. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:311.

- Devnani B, Kumar R, Pathy S, et al. Cutaneous metastases from neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: an unusual metastatic lesion from an uncommon malignancy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018; 42:527-533.

- Falto-Aizpurua L, Seyfer S, Krishnan B, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor. Cutis. 2017;99:E13-E15.

- Dhingra R, Tse JY, Saif MW. Cutaneous metastasis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-Nets)[published online September 8, 2018]. JOP. 2018;19.

- Jedrych J, Busam K, Klimstra DS, et al. Cutaneous metastases as an initial manifestation of visceral well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor: a report of four cases and a review of literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:113-122.

- Lloyd RV. Practical markers used in the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2003;14:293-301.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Calabuig-Fariñas S, et al. Superficial Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors: a clinicopathological study with differential diagnoses. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:636-643.

- D’Cruze L, Dutta R, Rao S, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in the analysis of the spectrum of small round cell tumours at a tertiary care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1377-1382.

- Chirila DN, Turdeanu NA, Constantea NA, et al. Multiple malignant tumors. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2013;108:498-502.

- Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1628-1638.

- Lin X, Saad RS, Luckasevic TM, et al. Diagnostic value of CDX-2 and TTF-1 expressions in separating metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms of unknown origin. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:407-414.

- Olney JR, Urdaneta LF, Al-Jurf AS, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1985;51:37-41.

- Strosberg JR, Halfdanarson TR, Bellizzi AM, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and medical management of midgut neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2017;46:707-714.

A 47-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with abdominal pain and flushing. She had a history of a midgut carcinoid that originated in the ileum with metastasis to the colon, liver, and pancreas. Dermatologic examination revealed a firm, nontender, mobile, 7-mm scalp nodule with a pink-purple overlying epidermis. The lesion was associated with a slight decrease in hair density. A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed.

Persistent Lip Swelling

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Cheilitis

A punch biopsy of the lip revealed a noncaseating microgranuloma in the submucosa with modest submucosal vascular ectasia and perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates (Figure). Comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood cell count, angiotensinconverting enzyme (ACE) levels, and inflammatory markers (ie, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) all were within reference range. A serum environmental allergen test was negative except for ragweed. Levels of complements—C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) antigen and function, C1q, C3, and C4—and antinuclear antibodies all were normal. Chest radiography was unremarkable. In lieu of a colonoscopy, a fecal calprotectin obtained by gastroenterology was normal. Given the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of granulomatous cheilitis (GC) was made.

Granulomatous cheilitis (also known as Miescher cheilitis) is an idiopathic condition characterized by recurrent or persistent swelling of one or both lips. Granulomatous cheilitis usually is an isolated finding but can occur in the setting of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, which refers to a triad of orofacial swelling, facial paralysis, and fissured tongue. Orofacial granulomatosis is a unifying term for any orofacial swelling associated with histologic findings of noncaseating granulomas without evidence of a systemic disease.

Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare disease that most commonly occurs in young adults without any sex predilection.1 The etiology still is unknown, but genetic predisposition, idiopathic influx of inflammatory cells, sensitivity to food or dental materials, and infections have been implicated.2 Granulomatous cheilitis initially presents as soft, nonerythematous, nontender swelling affecting one or both lips. The first episode usually resolves in hours or days, but the frequency and duration of the attacks may increase until the swelling becomes persistent and indurated.3 Granulomatous cheilitis often is a diagnosis of exclusion. A tissue biopsy may show noncaseating epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells with associated lymphedema and fibrosis4; however, histologic findings may be nonspecific, especially early in the disease course, and may be indistinguishable from those of other granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis and Crohn disease (CD).5

Lip swelling may be an oral manifestation of CD. Compared with GC, however, CD more commonly is associated with ulcerations, buccal sulcus involvement, abnormalities in complete blood cell count such as anemia and thrombocytosis, and elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although infrequent, GC may coincide with or precede the onset of CD.6 Thus, a detailed gastrointestinal history and appropriate laboratory tests are needed to rule out undiagnosed CD. Nevertheless, performing a routine colonoscopy in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms is debated.7,8

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease that can have oral involvement in the form of edema, nodules, or ulcers. Oral sarcoidosis usually occurs in patients with chronic multisystemic sarcoidosis and likely is accompanied by pulmonary manifestations such as hilar adenopathy and infiltrates on chest radiography, which are found in more than 90% of patients with sarcoidosis.9,10 A diagnosis of sarcoidosis is additionally supported by other organ involvement such as the joints, skin, or eyes, as well as elevated ACE and calcium levels.

Foreign bodies are another source of granulomatous inflammation and may present with nonspecific findings of swelling, masses, erythema, pain, or ulceration in oral tissues.11 Foreign body reactions to dental materials, retained sutures, and cosmetic fillers have been reported.12-14 In many cases, the foreign material is evident on biopsy.

Angioedema may mimic GC and should be excluded before more extensive testing is done, as it can result in life-threatening respiratory compromise. Numerous etiologies of angioedema have been identified including allergens, acquired or hereditary C1-INH deficiency, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ACE inhibitors, autoimmune disorders, and chronic infections.15 Patients with angioedema may have abnormalities in C4 and C1-INH levels or report certain medication use, allergen exposure, or family history of unexplained recurrent swellings or gastrointestinal symptoms.

There currently is no established treatment of GC due to the unclear etiology and unpredictable clinical course that can lead to spontaneous remissions or frequent recurrences. Corticosteroids administered systemically, intralesionally, or topically have been the mainstay treatment of GC.2 In particular, intralesional injections have been reported as effective in reducing swelling and preventing recurrences in several studies.16,17 Numerous other treatments have been reported in the literature with inconsistent outcomes, including antibiotics such as minocycline, metronidazole, and roxithromycin; clofazimine; thalidomide; immunomodulators such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and methotrexate; fumaric acid esters; and cheiloplasty in severe cases.16 Our patient showed near-complete resolution of the lip swelling after a single intralesional injection of 0.5 cc of triamcinolone acetonide 5 mg/mL. The patient has since received 5 additional maintenance injections of 0.1 to 0.2 cc of triamcinolone acetonide 2.5 to 5 mg/mL spaced 2 to 4 months apart with excellent control of the lip swelling, which the patient feels has resolved. We anticipate that repeated injections and monitoring of recurrences may be required for long-term remission.

- McCartan BE, Healy CM, McCreary CE, et al. Characteristics of patients with orofacial granulomatosis. Oral Dis. 2011;17:696-704.

- Grave B, McCullough M, Wiesenfeld D. Orofacial granulomatosis—a 20-year review. Oral Dis. 2009;15:46-51.