User login

Effect of Systemic Glucocorticoids on Mortality or Mechanical Ventilation in Patients With COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is the most important public health emergency of the 21st century. The pandemic has devastated New York City, where over 17,000 confirmed deaths have occurred as of June 5, 2020.1 The most common cause of death in COVID-19 patients is respiratory failure from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). A recent study reported high mortality rates among COVID-19 patients who received mechanical ventilation (MV).2

Glucocorticoids are useful as adjunctive treatment for some infections with inflammatory responses, but their efficacy in COVID-19 is unclear. Prior experience with influenza and other coronaviruses may be relevant. A recent meta-analysis of influenza pneumonia showed increased mortality and a higher rate of secondary infections in patients who were administered glucocorticoids.3 For Middle East respiratory syndrome, severe acute respiratory syndrome, and influenza, some studies have demonstrated an association between glucocorticoid use and delayed viral clearance.4-7 However, a recent retrospective series of patients with COVID-19 and ARDS demonstrated a decrease in mortality with glucocorticoid use.8 Glucocorticoids are easily obtained and familiar to providers caring for COVID-19 patients. Hence their empiric use is widespread.8,9

The primary goal of this study was to determine whether early glucocorticoid treatment is associated with reduced mortality or need for MV in COVID-19 patients.

METHODS

Study Setting and Overview

Montefiore Medical Center comprises four hospitals totaling 1,536 beds in the Bronx borough of New York, New York. Based upon early experience, some clinicians began prescribing systemic glucocorticoids to patients with COVID-19 while others did not. We leveraged this variation in practice to examine the effectiveness of glucocorticoids in reducing mortality and the rate of MV in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Study Populations

There were 2,998 patients admitted with a positive COVID-19 test between March 11, 2020, and April 13, 2020. An a priori decision was made to include all hospitalized COVID-19 patients, including children. Because the outcomes of in-hospital mortality and in-hospital MV cannot be assessed in patients still hospitalized, we included only patients who either died or had been discharged from the hospital. Patients who died or were placed on MV within the first 48 hours of admission were excluded because outcome events occurred before having the opportunity for glucocorticoid treatment. To ensure treatment preceded outcome measurement, we included only patients treated with glucocorticoids within the first 48 hours of admission (treatment group) and compared them with patients never treated with glucocorticoids (control group).

Outcomes and Independent Variables

The primary outcome was a composite of in-hospital mortality or in-hospital MV. Secondary outcomes were the components of the primary. Timing of MV was determined using the first documentation of a ventilator respiratory rate or tidal volume. The independent variable of interest was treatment with glucocorticoids within the first 48 hours of admission. Formulations included are described in the Appendix.

To compare treatment and control groups and to perform adjusted analyses, we also examined the demographic and clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and laboratory values of each admission. For the comparison of study populations, missing values for each variable were ignored. In the primary (unstratified) multivariable analysis, continuous variables were categorized, with missing values assumed to be normal when used as an adjustment variable. All variables extracted, number of missing values, candidates for inclusion in the multivariable analysis, and those that fell out of the model are presented in the Appendix. Several subgroup analyses were predefined including age, diabetes, admission glucose, C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer, and troponin T levels.

Statistical Analysis

The treated and control groups were compared with respect to demographics, clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and laboratory values. Primary and secondary outcomes in the groups were compared in unadjusted and adjusted analyses using univariable and multivariable logistic regression models. All patient characteristics that were candidates for inclusion in the adjustment models are listed in the Appendix. Variables were included in the final model if they were associated with the primary outcome (Wald test P < .20) in univariable regression. A sensitivity analysis excluded all variables missing greater than 10% of data, including CRP. Interactions between treatment and six predefined subgroups were tested using logistic regression with interaction terms (eg, [steroids]*[age]). Stratified logistic regression was used to test the association between treatment and the primary outcome in each of the predefined subgroups. Patients who were missing CRP were excluded from the stratified analysis. Because a significant interaction between treatment and initial CRP level was discovered, we undertook a post hoc adjusted analysis within each of the 15 predefined subgroup variables. Because there were fewer outcome events in each subgroup, we constructed a parsimonious logistic regression model that included all variables independently associated with the exposure (P < .05). The same seven adjustment variables were used in each of the predefined subgroups. The study was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Stata 15.1 software (StataCorp) was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

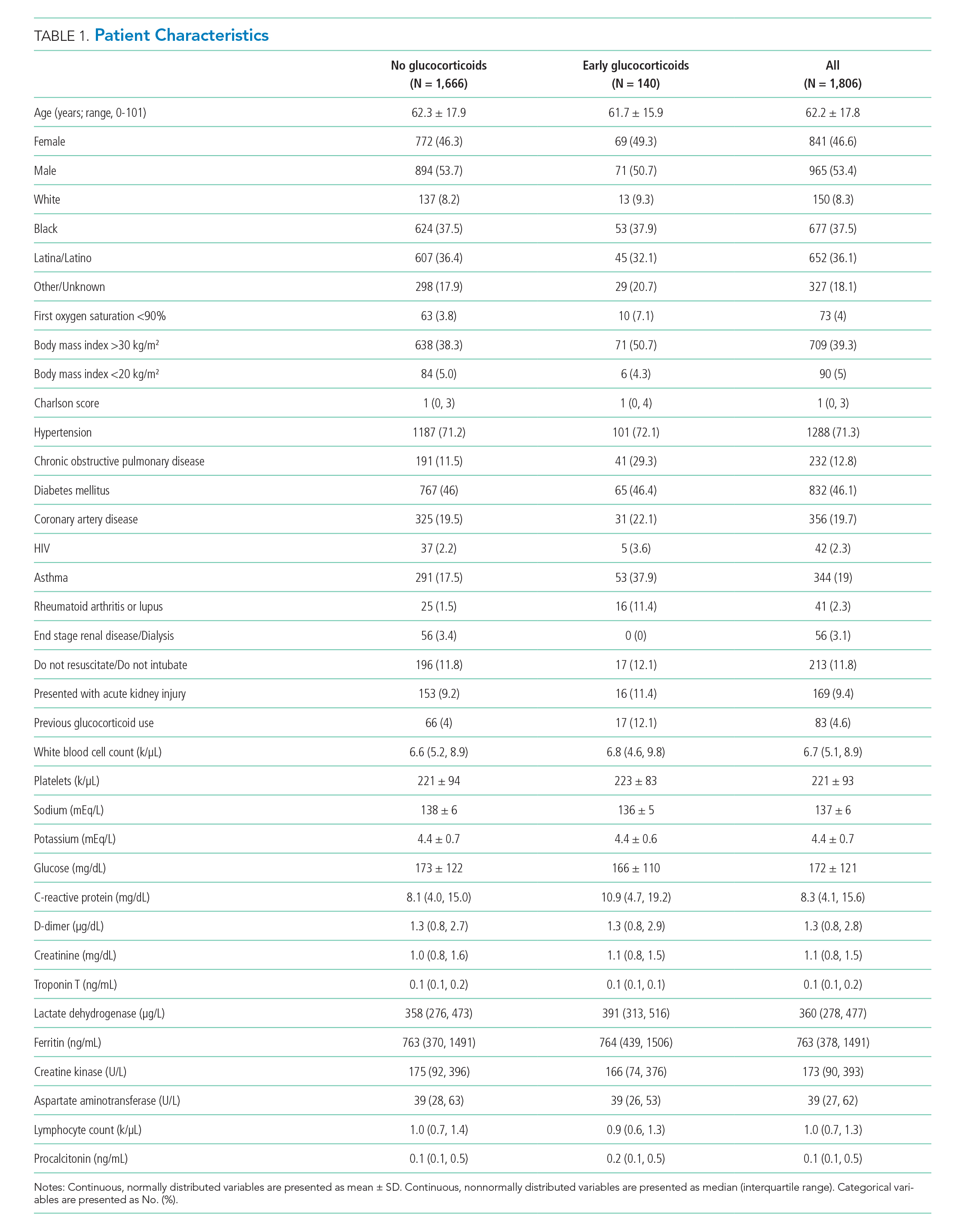

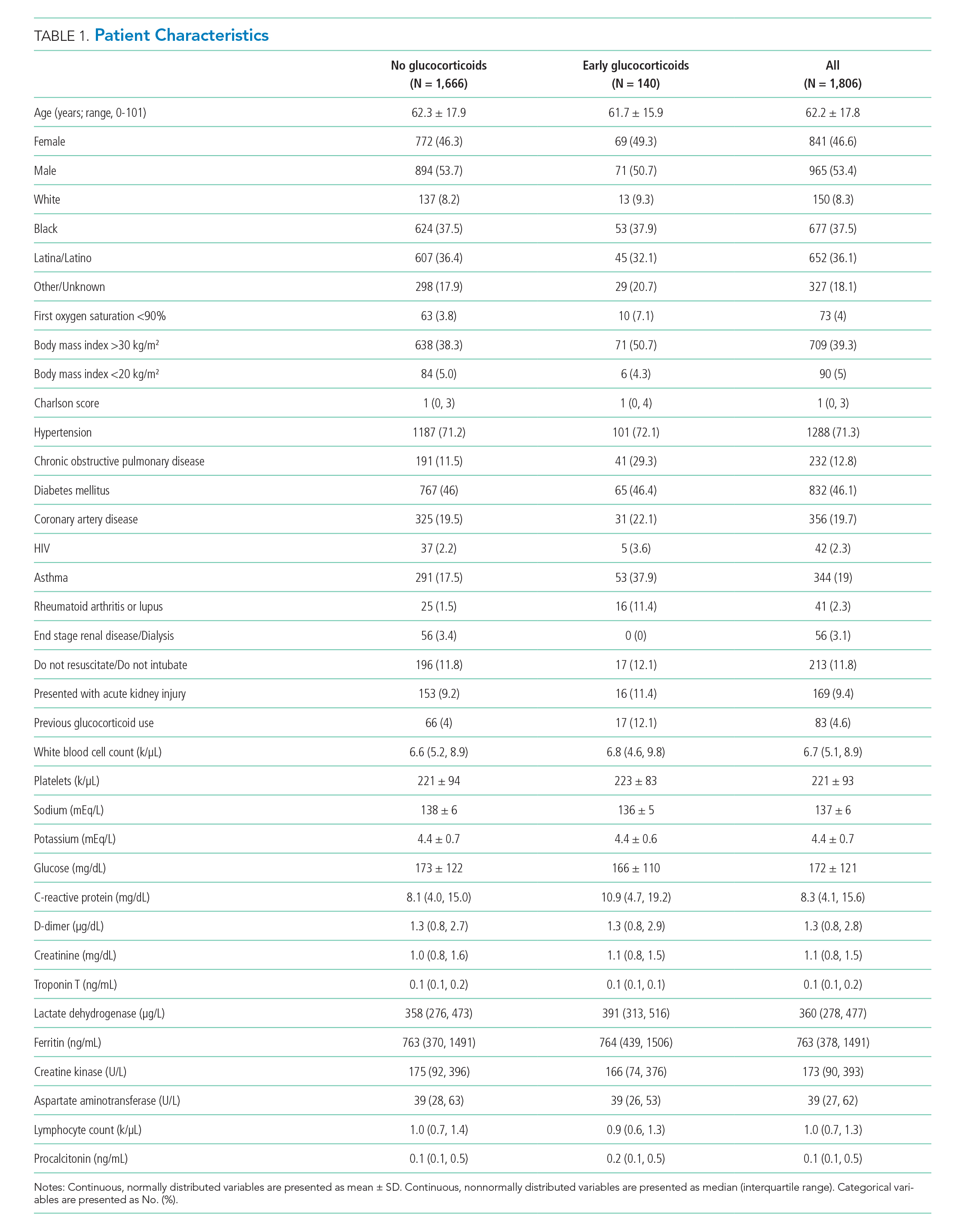

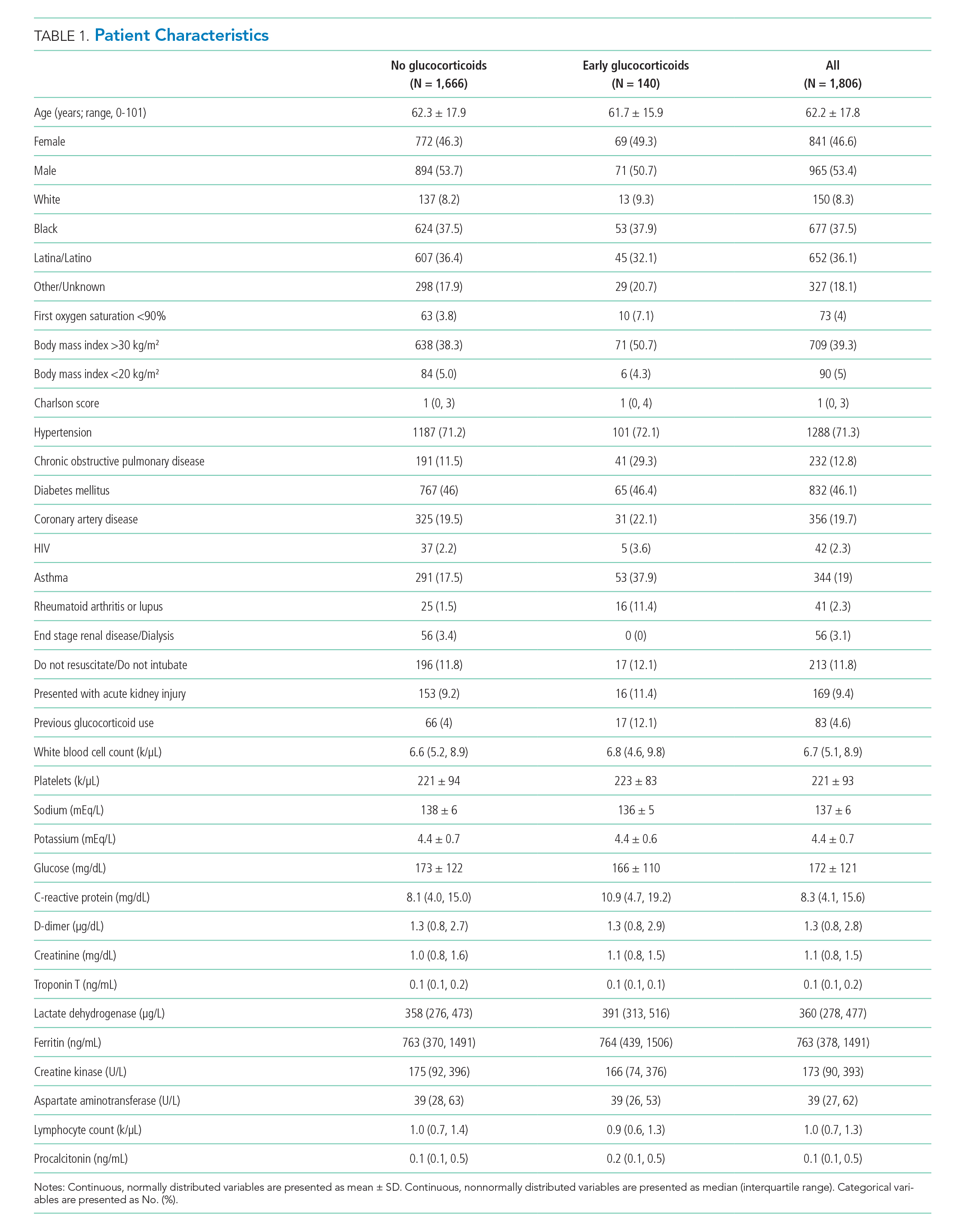

Of 2,998 patients examined, 1,806 met inclusion criteria and included 140 (7.7%) treated with glucocorticoids within 48 hours of admission and 1,666 who never received glucocorticoids. Reasons for exclusion of 1,192 patients are provided in the Appendix. Among patients who remained hospitalized and were excluded, 169 of 962 (17.6%) received glucocorticoids. Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Treatment and control groups were similar except that glucocorticoid-treated patients were more likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, or to have received glucocorticoids in the year prior to admission.

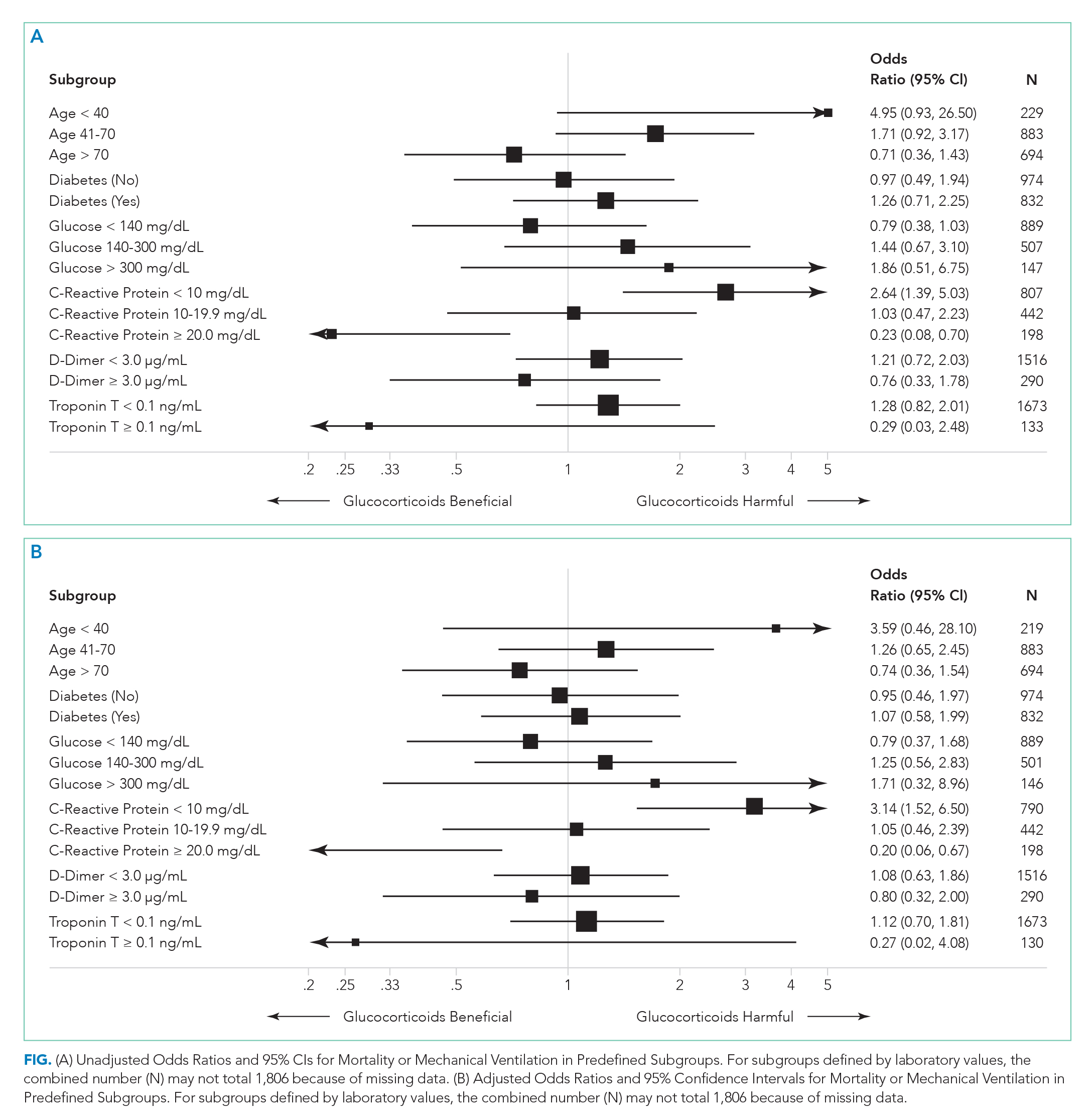

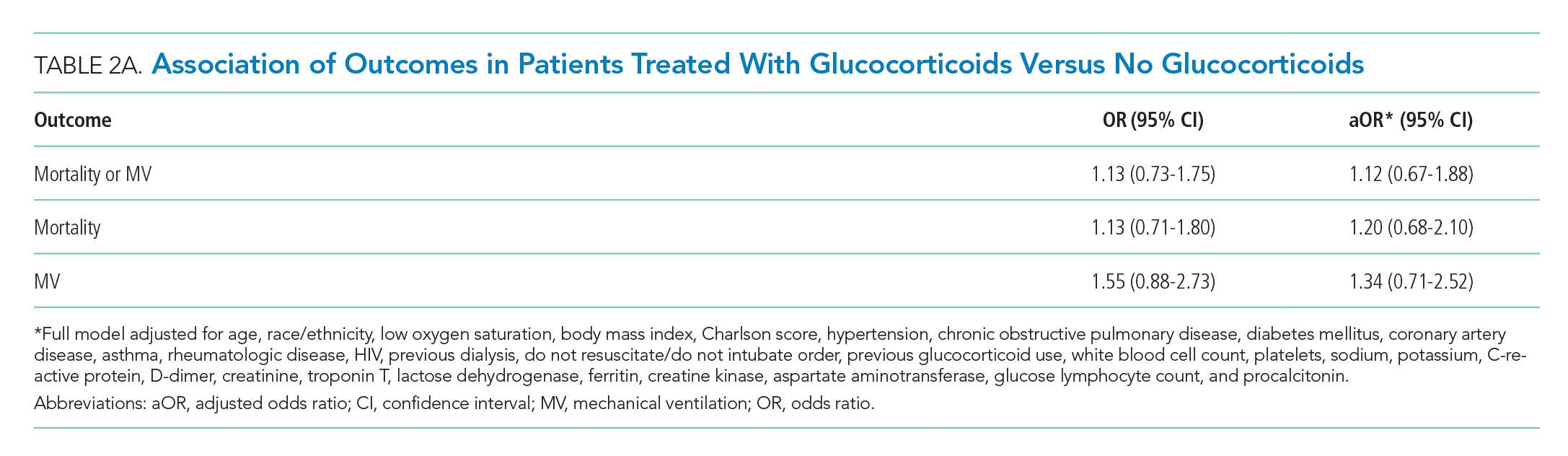

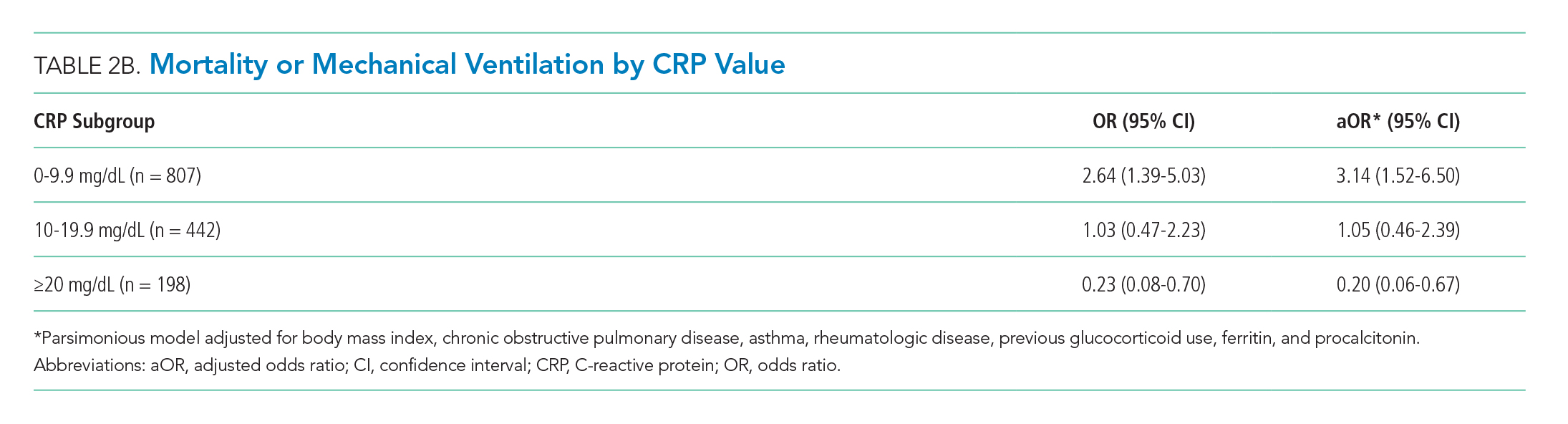

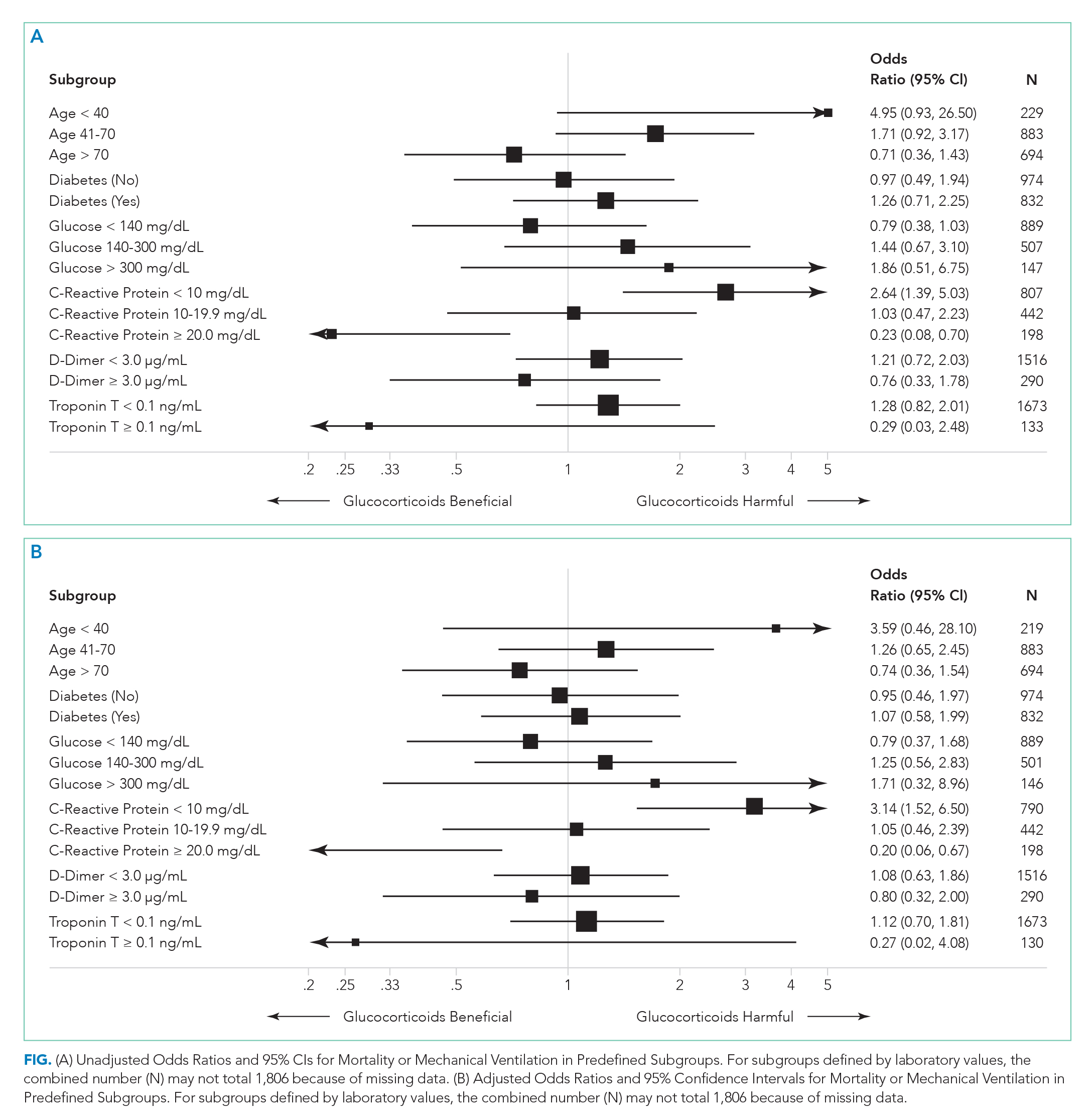

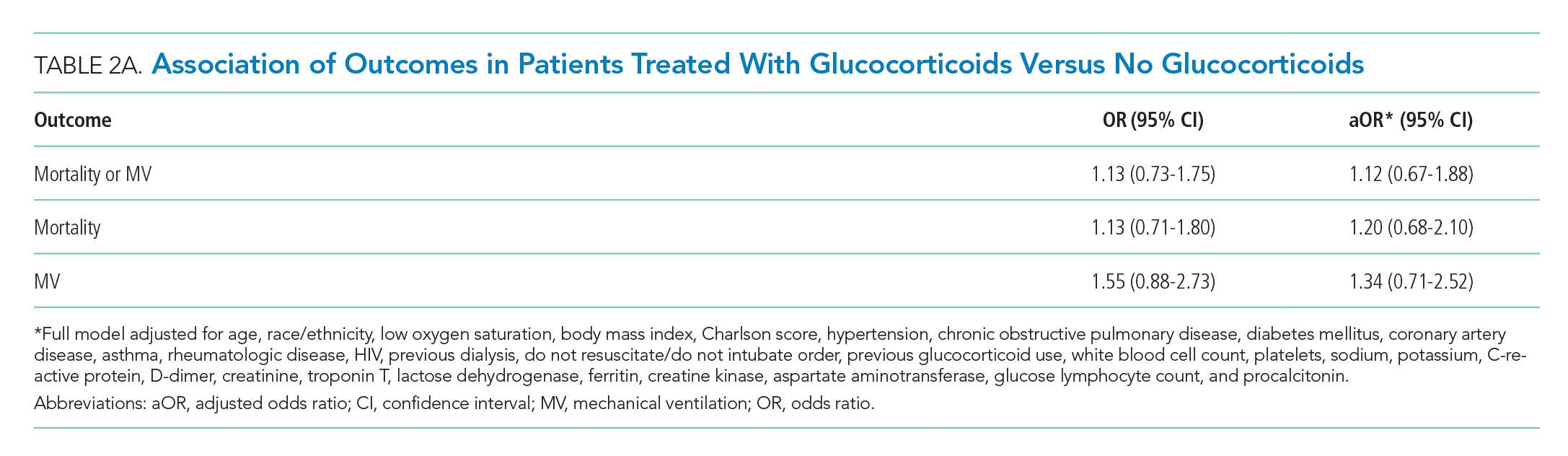

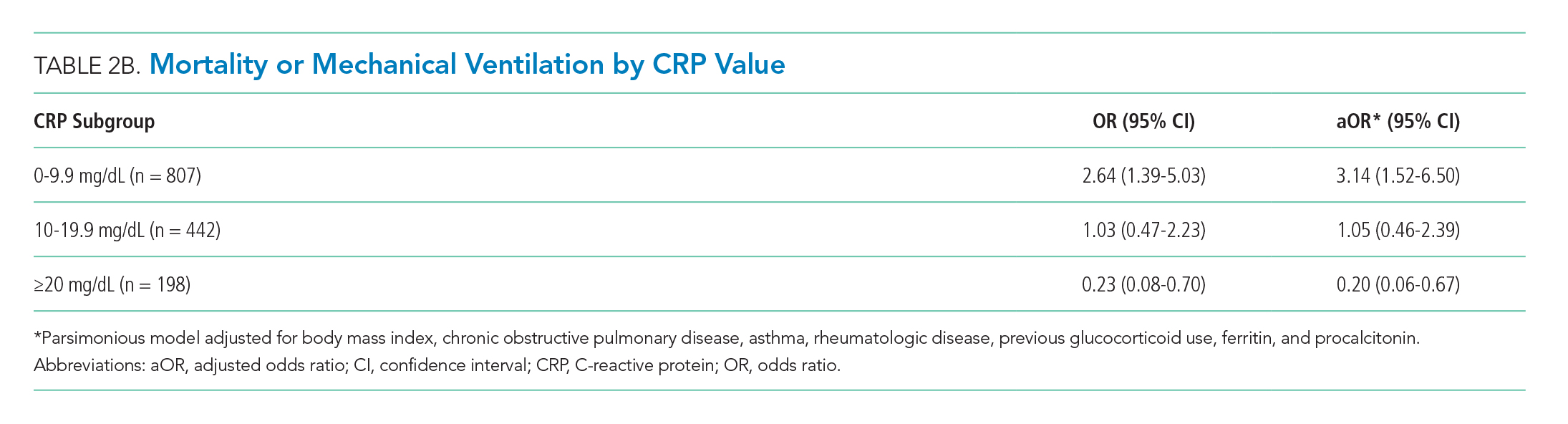

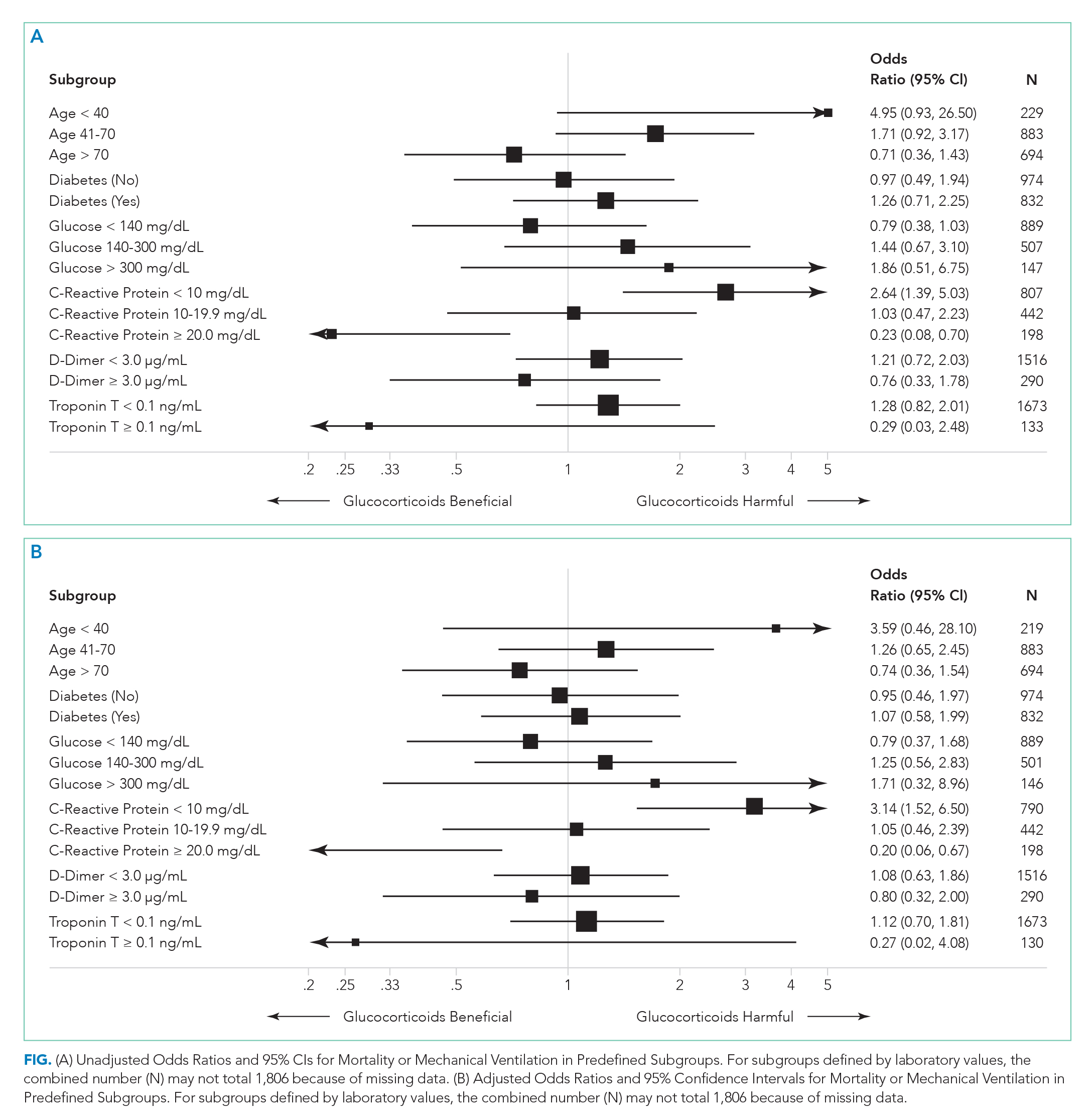

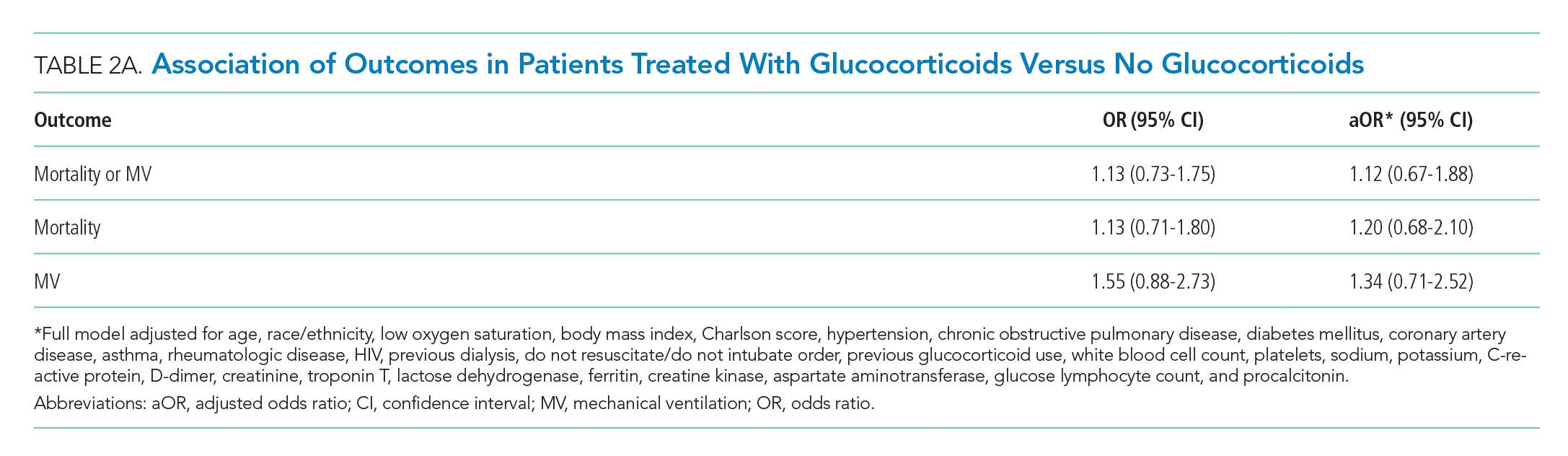

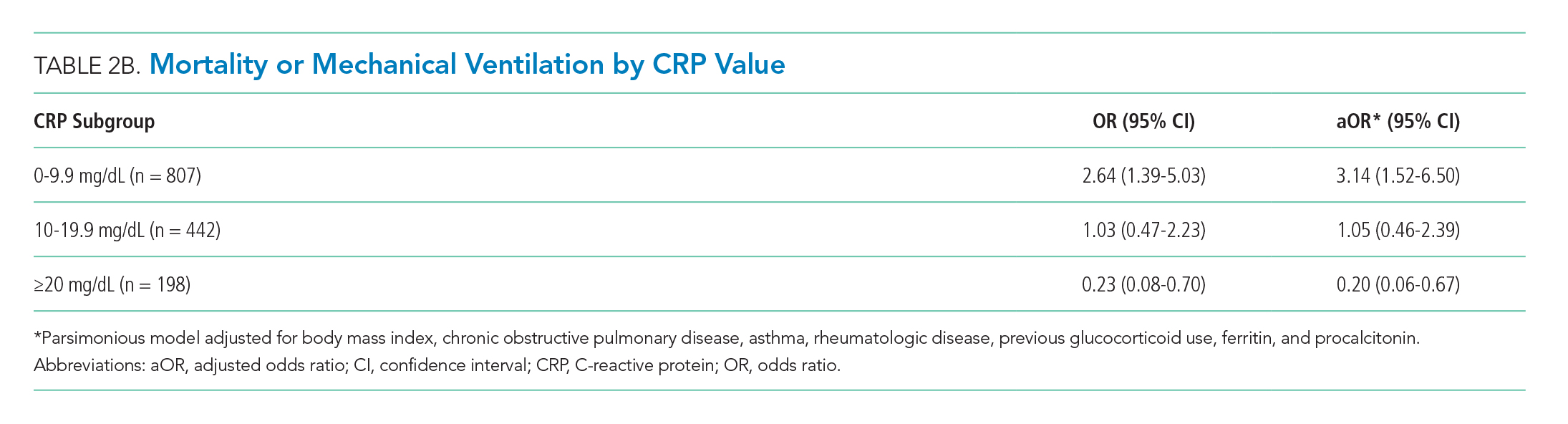

There were 318 who met the primary outcome of death or mechanical ventilation, 270 of whom died and 135 of whom required mechanical ventilation. Overall, early use of glucocorticoids was not associated with in-hospital mortality or MV as a composite outcome or as separate outcomes in both unadjusted and adjusted models (Table 2A). However, there was significant heterogeneity of treatment effect in the subgroups defined by CRP levels (P for interaction = .008; Figure). Early glucocorticoid use and an initial CRP of 20 mg/dL or higher was associated with a significantly reduced risk of mortality or MV in unadjusted (odds ratio, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.08-0.70) and adjusted (aOR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.06-0.67) analyses (Table 2B). Conversely, glucocorticoid treatment in patients with CRP levels less than 10 mg/dL was associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality or MV in unadjusted (OR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.39-5.03) and adjusted (aOR, 3.14; 95% CI, 1.52-6.50) analyses.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that early treatment with glucocorticoids is not associated with mortality or need for MV in unselected patients with COVID-19. Subgroup analyses suggest that glucocorticoid-treated patients with markedly elevated CRP may benefit from glucocorticoid treatment, whereas those patients with lower CRP may be harmed. Our findings were consistent after adjustment for clinical characteristics. The public health implications of these findings are hard to overestimate. Given the global growth of the pandemic and that glucocorticoids are widely available and inexpensive, glucocorticoid therapy may save many thousands of lives. Equally important because we have been able to identify a group that may be harmed, some patients may be saved because glucocorticoids will not be given.

Our study reaffirms the finding of the as yet unpublished Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial that there is a subset of patients with COVID-19 who benefit from treatment with glucocorticoids.10 Our study extends the findings of the RECOVERY trial in two important ways. First, in addition to finding some patients who may benefit, we also have identified patient groups that may experience harm from treatment with glucocorticoids. This finding suggests choosing the right patients for glucocorticoid treatment is critical to maximize the likelihood of benefit and minimize the risk of harm. Second, we have identified patient groups who are likely to benefit (or be harmed) on the basis of a widely available lab test (CRP).

Our results are also consistent with previous studies of patients with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, in which no associations between glucocorticoid treatment and mortality were found.7 However, the results of studies examining the effect of glucocorticoids in patients with COVID-19 are less consistent.8,11,12

Few of the previous studies examined the effects of glucocorticoids in subgroups of patients. In our study, the improved outcomes associated with glucocorticoid use in patients with elevated CRPs is intriguing and may be clinically important. Proinflammatory cytokines, especially interleukin-6, acutely increase CRP levels. Cytokine storm syndrome (CSS) is a hyperinflammatory condition that occurs in a subset of COVID-19 patients, often resulting in multiorgan dysfunction.13 CRP is markedly elevated in CSS,14 and improved outcomes with glucocorticoid therapy in this subgroup may indicate benefit in this inflammatory phenotype. Patients with lower CRP are less likely to have CSS and may experience more harm than benefit associated with glucocorticoid treatment.

Several limitations are inherent to this study. Since it was done at a single center, the results may not be generalizable. As a retrospective analysis, it is subject to confounding and bias. In addition, because patients were included only if they had reached the outcome of death/MV or hospital discharge, the sample size was truncated. We believe glucocorticoid use in hospitalized patients excluded from the study reflects increased use with time because of a growing belief in their effectiveness.

Preliminary analysis from the RECOVERY study showed a reduced rate of mortality in patients randomized to dexamethasone, compared with those who received standard of care.10 These results led to the National Institutes for Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel recommendation for dexamethasone treatment in patients with COVID-19 who require supplemental oxygen or MV.15 Our findings suggest a role for CRP to identify patients who may benefit from glucocorticoid therapy, as well as those in whom it may be harmful. Additional studies to further elucidate the role of CRP in guiding glucocorticoid therapy and to predict clinical response are needed.

1. COVID-19: Data. 2020. New York City Health. Accessed June 5, 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page

2. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6775

3. Ni YN, Chen G, Sun J, Liang BM, Liang ZA. The effect of corticosteroids on mortality of patients with influenza pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2395-8

4. Arabi YM, Alothman A, Balkhy HH, et al. Treatment of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome with a combination of lopinavir-ritonavir and interferon-beta1b (MIRACLE trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2427-0

5. Lee N, Allen Chan KC, Hui DS, et al. Effects of early corticosteroid treatment on plasma SARS-associated Coronavirus RNA concentrations in adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2004;31(4):304-309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2004.07.006

6. Lee N, Chan PK, Hui DS, et al. Viral loads and duration of viral shedding in adult patients hospitalized with influenza. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(4):492-500. https://doi.org/10.1086/600383

7. Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):473-475. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30317-2

8. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. Published online March 13, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994

9. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2002032

10. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson J, et al. Effect of dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: preliminary report. medRxiv. Preprint posted June 22, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.22.20137273

11. Cao J, Tu WJ, Cheng W, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 102 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. Published online April 2, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa243

12. Wang Y, Jiang W, He Q, et al. A retrospective cohort study of methylprednisolone therapy in severe patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):57. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-0158-2

13. Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2620-2629. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci137244

14. McGonagle D, Sharif K, O’Regan A, Bridgewood C. The role of cytokines including interleukin-6 in COVID-19 induced pneumonia and macrophage activation syndrome-like disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(6):102537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102537

15. The National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel Provides Recommendations for Dexamethasone in Patients with COVID-19. National Institutes of Health. Updated June 25, 2020. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/dexamethasone/

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is the most important public health emergency of the 21st century. The pandemic has devastated New York City, where over 17,000 confirmed deaths have occurred as of June 5, 2020.1 The most common cause of death in COVID-19 patients is respiratory failure from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). A recent study reported high mortality rates among COVID-19 patients who received mechanical ventilation (MV).2

Glucocorticoids are useful as adjunctive treatment for some infections with inflammatory responses, but their efficacy in COVID-19 is unclear. Prior experience with influenza and other coronaviruses may be relevant. A recent meta-analysis of influenza pneumonia showed increased mortality and a higher rate of secondary infections in patients who were administered glucocorticoids.3 For Middle East respiratory syndrome, severe acute respiratory syndrome, and influenza, some studies have demonstrated an association between glucocorticoid use and delayed viral clearance.4-7 However, a recent retrospective series of patients with COVID-19 and ARDS demonstrated a decrease in mortality with glucocorticoid use.8 Glucocorticoids are easily obtained and familiar to providers caring for COVID-19 patients. Hence their empiric use is widespread.8,9

The primary goal of this study was to determine whether early glucocorticoid treatment is associated with reduced mortality or need for MV in COVID-19 patients.

METHODS

Study Setting and Overview

Montefiore Medical Center comprises four hospitals totaling 1,536 beds in the Bronx borough of New York, New York. Based upon early experience, some clinicians began prescribing systemic glucocorticoids to patients with COVID-19 while others did not. We leveraged this variation in practice to examine the effectiveness of glucocorticoids in reducing mortality and the rate of MV in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Study Populations

There were 2,998 patients admitted with a positive COVID-19 test between March 11, 2020, and April 13, 2020. An a priori decision was made to include all hospitalized COVID-19 patients, including children. Because the outcomes of in-hospital mortality and in-hospital MV cannot be assessed in patients still hospitalized, we included only patients who either died or had been discharged from the hospital. Patients who died or were placed on MV within the first 48 hours of admission were excluded because outcome events occurred before having the opportunity for glucocorticoid treatment. To ensure treatment preceded outcome measurement, we included only patients treated with glucocorticoids within the first 48 hours of admission (treatment group) and compared them with patients never treated with glucocorticoids (control group).

Outcomes and Independent Variables

The primary outcome was a composite of in-hospital mortality or in-hospital MV. Secondary outcomes were the components of the primary. Timing of MV was determined using the first documentation of a ventilator respiratory rate or tidal volume. The independent variable of interest was treatment with glucocorticoids within the first 48 hours of admission. Formulations included are described in the Appendix.

To compare treatment and control groups and to perform adjusted analyses, we also examined the demographic and clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and laboratory values of each admission. For the comparison of study populations, missing values for each variable were ignored. In the primary (unstratified) multivariable analysis, continuous variables were categorized, with missing values assumed to be normal when used as an adjustment variable. All variables extracted, number of missing values, candidates for inclusion in the multivariable analysis, and those that fell out of the model are presented in the Appendix. Several subgroup analyses were predefined including age, diabetes, admission glucose, C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer, and troponin T levels.

Statistical Analysis

The treated and control groups were compared with respect to demographics, clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and laboratory values. Primary and secondary outcomes in the groups were compared in unadjusted and adjusted analyses using univariable and multivariable logistic regression models. All patient characteristics that were candidates for inclusion in the adjustment models are listed in the Appendix. Variables were included in the final model if they were associated with the primary outcome (Wald test P < .20) in univariable regression. A sensitivity analysis excluded all variables missing greater than 10% of data, including CRP. Interactions between treatment and six predefined subgroups were tested using logistic regression with interaction terms (eg, [steroids]*[age]). Stratified logistic regression was used to test the association between treatment and the primary outcome in each of the predefined subgroups. Patients who were missing CRP were excluded from the stratified analysis. Because a significant interaction between treatment and initial CRP level was discovered, we undertook a post hoc adjusted analysis within each of the 15 predefined subgroup variables. Because there were fewer outcome events in each subgroup, we constructed a parsimonious logistic regression model that included all variables independently associated with the exposure (P < .05). The same seven adjustment variables were used in each of the predefined subgroups. The study was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Stata 15.1 software (StataCorp) was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

Of 2,998 patients examined, 1,806 met inclusion criteria and included 140 (7.7%) treated with glucocorticoids within 48 hours of admission and 1,666 who never received glucocorticoids. Reasons for exclusion of 1,192 patients are provided in the Appendix. Among patients who remained hospitalized and were excluded, 169 of 962 (17.6%) received glucocorticoids. Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Treatment and control groups were similar except that glucocorticoid-treated patients were more likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, or to have received glucocorticoids in the year prior to admission.

There were 318 who met the primary outcome of death or mechanical ventilation, 270 of whom died and 135 of whom required mechanical ventilation. Overall, early use of glucocorticoids was not associated with in-hospital mortality or MV as a composite outcome or as separate outcomes in both unadjusted and adjusted models (Table 2A). However, there was significant heterogeneity of treatment effect in the subgroups defined by CRP levels (P for interaction = .008; Figure). Early glucocorticoid use and an initial CRP of 20 mg/dL or higher was associated with a significantly reduced risk of mortality or MV in unadjusted (odds ratio, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.08-0.70) and adjusted (aOR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.06-0.67) analyses (Table 2B). Conversely, glucocorticoid treatment in patients with CRP levels less than 10 mg/dL was associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality or MV in unadjusted (OR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.39-5.03) and adjusted (aOR, 3.14; 95% CI, 1.52-6.50) analyses.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that early treatment with glucocorticoids is not associated with mortality or need for MV in unselected patients with COVID-19. Subgroup analyses suggest that glucocorticoid-treated patients with markedly elevated CRP may benefit from glucocorticoid treatment, whereas those patients with lower CRP may be harmed. Our findings were consistent after adjustment for clinical characteristics. The public health implications of these findings are hard to overestimate. Given the global growth of the pandemic and that glucocorticoids are widely available and inexpensive, glucocorticoid therapy may save many thousands of lives. Equally important because we have been able to identify a group that may be harmed, some patients may be saved because glucocorticoids will not be given.

Our study reaffirms the finding of the as yet unpublished Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial that there is a subset of patients with COVID-19 who benefit from treatment with glucocorticoids.10 Our study extends the findings of the RECOVERY trial in two important ways. First, in addition to finding some patients who may benefit, we also have identified patient groups that may experience harm from treatment with glucocorticoids. This finding suggests choosing the right patients for glucocorticoid treatment is critical to maximize the likelihood of benefit and minimize the risk of harm. Second, we have identified patient groups who are likely to benefit (or be harmed) on the basis of a widely available lab test (CRP).

Our results are also consistent with previous studies of patients with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, in which no associations between glucocorticoid treatment and mortality were found.7 However, the results of studies examining the effect of glucocorticoids in patients with COVID-19 are less consistent.8,11,12

Few of the previous studies examined the effects of glucocorticoids in subgroups of patients. In our study, the improved outcomes associated with glucocorticoid use in patients with elevated CRPs is intriguing and may be clinically important. Proinflammatory cytokines, especially interleukin-6, acutely increase CRP levels. Cytokine storm syndrome (CSS) is a hyperinflammatory condition that occurs in a subset of COVID-19 patients, often resulting in multiorgan dysfunction.13 CRP is markedly elevated in CSS,14 and improved outcomes with glucocorticoid therapy in this subgroup may indicate benefit in this inflammatory phenotype. Patients with lower CRP are less likely to have CSS and may experience more harm than benefit associated with glucocorticoid treatment.

Several limitations are inherent to this study. Since it was done at a single center, the results may not be generalizable. As a retrospective analysis, it is subject to confounding and bias. In addition, because patients were included only if they had reached the outcome of death/MV or hospital discharge, the sample size was truncated. We believe glucocorticoid use in hospitalized patients excluded from the study reflects increased use with time because of a growing belief in their effectiveness.

Preliminary analysis from the RECOVERY study showed a reduced rate of mortality in patients randomized to dexamethasone, compared with those who received standard of care.10 These results led to the National Institutes for Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel recommendation for dexamethasone treatment in patients with COVID-19 who require supplemental oxygen or MV.15 Our findings suggest a role for CRP to identify patients who may benefit from glucocorticoid therapy, as well as those in whom it may be harmful. Additional studies to further elucidate the role of CRP in guiding glucocorticoid therapy and to predict clinical response are needed.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is the most important public health emergency of the 21st century. The pandemic has devastated New York City, where over 17,000 confirmed deaths have occurred as of June 5, 2020.1 The most common cause of death in COVID-19 patients is respiratory failure from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). A recent study reported high mortality rates among COVID-19 patients who received mechanical ventilation (MV).2

Glucocorticoids are useful as adjunctive treatment for some infections with inflammatory responses, but their efficacy in COVID-19 is unclear. Prior experience with influenza and other coronaviruses may be relevant. A recent meta-analysis of influenza pneumonia showed increased mortality and a higher rate of secondary infections in patients who were administered glucocorticoids.3 For Middle East respiratory syndrome, severe acute respiratory syndrome, and influenza, some studies have demonstrated an association between glucocorticoid use and delayed viral clearance.4-7 However, a recent retrospective series of patients with COVID-19 and ARDS demonstrated a decrease in mortality with glucocorticoid use.8 Glucocorticoids are easily obtained and familiar to providers caring for COVID-19 patients. Hence their empiric use is widespread.8,9

The primary goal of this study was to determine whether early glucocorticoid treatment is associated with reduced mortality or need for MV in COVID-19 patients.

METHODS

Study Setting and Overview

Montefiore Medical Center comprises four hospitals totaling 1,536 beds in the Bronx borough of New York, New York. Based upon early experience, some clinicians began prescribing systemic glucocorticoids to patients with COVID-19 while others did not. We leveraged this variation in practice to examine the effectiveness of glucocorticoids in reducing mortality and the rate of MV in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Study Populations

There were 2,998 patients admitted with a positive COVID-19 test between March 11, 2020, and April 13, 2020. An a priori decision was made to include all hospitalized COVID-19 patients, including children. Because the outcomes of in-hospital mortality and in-hospital MV cannot be assessed in patients still hospitalized, we included only patients who either died or had been discharged from the hospital. Patients who died or were placed on MV within the first 48 hours of admission were excluded because outcome events occurred before having the opportunity for glucocorticoid treatment. To ensure treatment preceded outcome measurement, we included only patients treated with glucocorticoids within the first 48 hours of admission (treatment group) and compared them with patients never treated with glucocorticoids (control group).

Outcomes and Independent Variables

The primary outcome was a composite of in-hospital mortality or in-hospital MV. Secondary outcomes were the components of the primary. Timing of MV was determined using the first documentation of a ventilator respiratory rate or tidal volume. The independent variable of interest was treatment with glucocorticoids within the first 48 hours of admission. Formulations included are described in the Appendix.

To compare treatment and control groups and to perform adjusted analyses, we also examined the demographic and clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and laboratory values of each admission. For the comparison of study populations, missing values for each variable were ignored. In the primary (unstratified) multivariable analysis, continuous variables were categorized, with missing values assumed to be normal when used as an adjustment variable. All variables extracted, number of missing values, candidates for inclusion in the multivariable analysis, and those that fell out of the model are presented in the Appendix. Several subgroup analyses were predefined including age, diabetes, admission glucose, C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer, and troponin T levels.

Statistical Analysis

The treated and control groups were compared with respect to demographics, clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and laboratory values. Primary and secondary outcomes in the groups were compared in unadjusted and adjusted analyses using univariable and multivariable logistic regression models. All patient characteristics that were candidates for inclusion in the adjustment models are listed in the Appendix. Variables were included in the final model if they were associated with the primary outcome (Wald test P < .20) in univariable regression. A sensitivity analysis excluded all variables missing greater than 10% of data, including CRP. Interactions between treatment and six predefined subgroups were tested using logistic regression with interaction terms (eg, [steroids]*[age]). Stratified logistic regression was used to test the association between treatment and the primary outcome in each of the predefined subgroups. Patients who were missing CRP were excluded from the stratified analysis. Because a significant interaction between treatment and initial CRP level was discovered, we undertook a post hoc adjusted analysis within each of the 15 predefined subgroup variables. Because there were fewer outcome events in each subgroup, we constructed a parsimonious logistic regression model that included all variables independently associated with the exposure (P < .05). The same seven adjustment variables were used in each of the predefined subgroups. The study was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Stata 15.1 software (StataCorp) was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

Of 2,998 patients examined, 1,806 met inclusion criteria and included 140 (7.7%) treated with glucocorticoids within 48 hours of admission and 1,666 who never received glucocorticoids. Reasons for exclusion of 1,192 patients are provided in the Appendix. Among patients who remained hospitalized and were excluded, 169 of 962 (17.6%) received glucocorticoids. Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Treatment and control groups were similar except that glucocorticoid-treated patients were more likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, or to have received glucocorticoids in the year prior to admission.

There were 318 who met the primary outcome of death or mechanical ventilation, 270 of whom died and 135 of whom required mechanical ventilation. Overall, early use of glucocorticoids was not associated with in-hospital mortality or MV as a composite outcome or as separate outcomes in both unadjusted and adjusted models (Table 2A). However, there was significant heterogeneity of treatment effect in the subgroups defined by CRP levels (P for interaction = .008; Figure). Early glucocorticoid use and an initial CRP of 20 mg/dL or higher was associated with a significantly reduced risk of mortality or MV in unadjusted (odds ratio, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.08-0.70) and adjusted (aOR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.06-0.67) analyses (Table 2B). Conversely, glucocorticoid treatment in patients with CRP levels less than 10 mg/dL was associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality or MV in unadjusted (OR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.39-5.03) and adjusted (aOR, 3.14; 95% CI, 1.52-6.50) analyses.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that early treatment with glucocorticoids is not associated with mortality or need for MV in unselected patients with COVID-19. Subgroup analyses suggest that glucocorticoid-treated patients with markedly elevated CRP may benefit from glucocorticoid treatment, whereas those patients with lower CRP may be harmed. Our findings were consistent after adjustment for clinical characteristics. The public health implications of these findings are hard to overestimate. Given the global growth of the pandemic and that glucocorticoids are widely available and inexpensive, glucocorticoid therapy may save many thousands of lives. Equally important because we have been able to identify a group that may be harmed, some patients may be saved because glucocorticoids will not be given.

Our study reaffirms the finding of the as yet unpublished Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial that there is a subset of patients with COVID-19 who benefit from treatment with glucocorticoids.10 Our study extends the findings of the RECOVERY trial in two important ways. First, in addition to finding some patients who may benefit, we also have identified patient groups that may experience harm from treatment with glucocorticoids. This finding suggests choosing the right patients for glucocorticoid treatment is critical to maximize the likelihood of benefit and minimize the risk of harm. Second, we have identified patient groups who are likely to benefit (or be harmed) on the basis of a widely available lab test (CRP).

Our results are also consistent with previous studies of patients with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, in which no associations between glucocorticoid treatment and mortality were found.7 However, the results of studies examining the effect of glucocorticoids in patients with COVID-19 are less consistent.8,11,12

Few of the previous studies examined the effects of glucocorticoids in subgroups of patients. In our study, the improved outcomes associated with glucocorticoid use in patients with elevated CRPs is intriguing and may be clinically important. Proinflammatory cytokines, especially interleukin-6, acutely increase CRP levels. Cytokine storm syndrome (CSS) is a hyperinflammatory condition that occurs in a subset of COVID-19 patients, often resulting in multiorgan dysfunction.13 CRP is markedly elevated in CSS,14 and improved outcomes with glucocorticoid therapy in this subgroup may indicate benefit in this inflammatory phenotype. Patients with lower CRP are less likely to have CSS and may experience more harm than benefit associated with glucocorticoid treatment.

Several limitations are inherent to this study. Since it was done at a single center, the results may not be generalizable. As a retrospective analysis, it is subject to confounding and bias. In addition, because patients were included only if they had reached the outcome of death/MV or hospital discharge, the sample size was truncated. We believe glucocorticoid use in hospitalized patients excluded from the study reflects increased use with time because of a growing belief in their effectiveness.

Preliminary analysis from the RECOVERY study showed a reduced rate of mortality in patients randomized to dexamethasone, compared with those who received standard of care.10 These results led to the National Institutes for Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel recommendation for dexamethasone treatment in patients with COVID-19 who require supplemental oxygen or MV.15 Our findings suggest a role for CRP to identify patients who may benefit from glucocorticoid therapy, as well as those in whom it may be harmful. Additional studies to further elucidate the role of CRP in guiding glucocorticoid therapy and to predict clinical response are needed.

1. COVID-19: Data. 2020. New York City Health. Accessed June 5, 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page

2. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6775

3. Ni YN, Chen G, Sun J, Liang BM, Liang ZA. The effect of corticosteroids on mortality of patients with influenza pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2395-8

4. Arabi YM, Alothman A, Balkhy HH, et al. Treatment of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome with a combination of lopinavir-ritonavir and interferon-beta1b (MIRACLE trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2427-0

5. Lee N, Allen Chan KC, Hui DS, et al. Effects of early corticosteroid treatment on plasma SARS-associated Coronavirus RNA concentrations in adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2004;31(4):304-309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2004.07.006

6. Lee N, Chan PK, Hui DS, et al. Viral loads and duration of viral shedding in adult patients hospitalized with influenza. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(4):492-500. https://doi.org/10.1086/600383

7. Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):473-475. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30317-2

8. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. Published online March 13, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994

9. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2002032

10. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson J, et al. Effect of dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: preliminary report. medRxiv. Preprint posted June 22, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.22.20137273

11. Cao J, Tu WJ, Cheng W, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 102 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. Published online April 2, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa243

12. Wang Y, Jiang W, He Q, et al. A retrospective cohort study of methylprednisolone therapy in severe patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):57. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-0158-2

13. Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2620-2629. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci137244

14. McGonagle D, Sharif K, O’Regan A, Bridgewood C. The role of cytokines including interleukin-6 in COVID-19 induced pneumonia and macrophage activation syndrome-like disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(6):102537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102537

15. The National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel Provides Recommendations for Dexamethasone in Patients with COVID-19. National Institutes of Health. Updated June 25, 2020. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/dexamethasone/

1. COVID-19: Data. 2020. New York City Health. Accessed June 5, 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page

2. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6775

3. Ni YN, Chen G, Sun J, Liang BM, Liang ZA. The effect of corticosteroids on mortality of patients with influenza pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2395-8

4. Arabi YM, Alothman A, Balkhy HH, et al. Treatment of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome with a combination of lopinavir-ritonavir and interferon-beta1b (MIRACLE trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2427-0

5. Lee N, Allen Chan KC, Hui DS, et al. Effects of early corticosteroid treatment on plasma SARS-associated Coronavirus RNA concentrations in adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2004;31(4):304-309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2004.07.006

6. Lee N, Chan PK, Hui DS, et al. Viral loads and duration of viral shedding in adult patients hospitalized with influenza. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(4):492-500. https://doi.org/10.1086/600383

7. Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):473-475. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30317-2

8. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. Published online March 13, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994

9. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2002032

10. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson J, et al. Effect of dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: preliminary report. medRxiv. Preprint posted June 22, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.22.20137273

11. Cao J, Tu WJ, Cheng W, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 102 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. Published online April 2, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa243

12. Wang Y, Jiang W, He Q, et al. A retrospective cohort study of methylprednisolone therapy in severe patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):57. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-0158-2

13. Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2620-2629. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci137244

14. McGonagle D, Sharif K, O’Regan A, Bridgewood C. The role of cytokines including interleukin-6 in COVID-19 induced pneumonia and macrophage activation syndrome-like disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(6):102537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102537

15. The National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel Provides Recommendations for Dexamethasone in Patients with COVID-19. National Institutes of Health. Updated June 25, 2020. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/dexamethasone/

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Streamlining the transition from pediatric to adult care

Diabetes is a complex disease with a range of nuanced therapy options and a plethora of risk factors that could significantly affect patient quality of life and long-term outcomes. From the outset, after diagnosis, a selected regimen has to be meticulously tailored to a patient’s clinical needs and monitored over time, and many other nonclinical variables, such as patient preference, social history, access to care, and support systems, as well as the cost of the drugs and its impact on the patient, must also be considered.

The increase in the incidence of youth-onset diabetes means that more young adults are making the transition from pediatric to adult care, and careful care coordination is paramount at the handover point to ensure that a full and complete account of the history gets transferred to the adult-care provider.

So how do you distill the information from all those records (on paper and online) that you’ve accumulated during the time you’ve been treating a young adult who is now transitioning to adult care?

Transition summary

One resource that can facilitate this handover is the transition summary. It effectively consolidates and packages the aforementioned aspects of care and patient history so that the adult-care provider does not have to collect the patient’s history from the start. The transition summary should not be confused with the discharge or medical summary, which focuses only on the preceding clinical care.

It is important to stress at this stage that collaboration between the pediatric- and adult-care providers is crucial to the success of such a summary, from its creation, to its implementation, and through the subsequent and inevitable revisions and updates.

Benefits all around

After we introduced the transition summary at my institution, we found that the average initial patient visit with the new adult-care provider decreased by 12 minutes (with a range of 6-19 min). The adult-care providers welcomed receiving such detailed, important patient information packaged in a concise and readily accessible format. It helped them identify the preceding care team members, which facilitated continuity of care, and it also helped them forge a better therapeutic relationship with the patient earlier on in their engagement.

We also learned that patients were more comfortable with the transition, and the referring providers were relieved and reassured that their patients would continue to receive personalized care with the new adult-care provider.

At a personal level, I found I was less stressed as I could spend better-quality clinical time with patients. And I got to eliminate those unwieldy stacks of medical records since getting buy-in from divisional and IT leadership enabled us to automate the entire process of information transfer.

It is important to note that the patient has to consent to release of medical records to other institutions.

Setting up the summary

At our clinic, I started out by adapting the transition summary from guidelines provided by the Endocrine Society to make a template. Then, in collaboration with my pediatric colleagues, I removed and added information so that the revised document would contain information that is vitally important and not readily available in the chart and would be feasible to fill out. For example, we included details such as the patient’s psychosocial history, an estimation of the patient barriers to diabetes management, family relationship issues, and the patient’s reasons for not adopting advanced diabetes technology (see accompanying example of a transition summary) .

I kept the summary brief, at two pages, and piloted it with referring providers who were interested in using the summary and with related supporting services. I also sought buy-in from my institution. This meant that I needed pediatric and adult divisional leadership support, which offered me information technology, resources, and expertise to automate the summary within the electronic health record. Once I had feedback from would-be users, we revised and updated the summary. We set up training for staff, including pediatric providers, nurse practitioners, social workers, and nurses who could fill out the summary, and ultimately succeeded in making it mandatory that the adult-care provider receive a summary before scheduling or seeing the transfer patient.

I started out with a paper version, and once we’d refined the questions, we incorporated it into the electronic medical record.

The information we use in our summary is grouped under the following headings:

- Reason for transition.

- Diabetes type.

- Degree of diabetes control.

- Type of insulin therapy and supplies.

- Current and former insulin regimen: reasons for discontinuation of any therapies or reluctance to start any therapies.

- Diabetes health maintenance.

- Social history and support, including living situation, main social support network, child protective services involvement.

- Other pertinent medical surgical history, including psychiatric disease.

Tips and takeaways

Top of the list of takeaways is that you should make the final document work for you, your colleagues, and ultimately, your patients – customize it as you see fit, but be sure to keep it short and easy to fill out. Make a note as you start using it in practice of what you think might be missing from the chart and whether updates are needed. If you can, it’s a great idea to fold the transfer summary into the electronic medical record, though it’s not imperative. Care coordination is key to successful transfer of patients, whether from pediatric to adult care or hospital to home. A small change to work flow can result in a huge change in patient and provider satisfaction, as well as a reduction in visit times.

Dr. Agarwal is director of the Supporting Emerging Adults With Diabetes (SEAD) program at Montefiore Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York. She reports no disclosures or financial conflicts of interest. Write to her at cenews@mdedge.com.

Diabetes is a complex disease with a range of nuanced therapy options and a plethora of risk factors that could significantly affect patient quality of life and long-term outcomes. From the outset, after diagnosis, a selected regimen has to be meticulously tailored to a patient’s clinical needs and monitored over time, and many other nonclinical variables, such as patient preference, social history, access to care, and support systems, as well as the cost of the drugs and its impact on the patient, must also be considered.

The increase in the incidence of youth-onset diabetes means that more young adults are making the transition from pediatric to adult care, and careful care coordination is paramount at the handover point to ensure that a full and complete account of the history gets transferred to the adult-care provider.

So how do you distill the information from all those records (on paper and online) that you’ve accumulated during the time you’ve been treating a young adult who is now transitioning to adult care?

Transition summary

One resource that can facilitate this handover is the transition summary. It effectively consolidates and packages the aforementioned aspects of care and patient history so that the adult-care provider does not have to collect the patient’s history from the start. The transition summary should not be confused with the discharge or medical summary, which focuses only on the preceding clinical care.

It is important to stress at this stage that collaboration between the pediatric- and adult-care providers is crucial to the success of such a summary, from its creation, to its implementation, and through the subsequent and inevitable revisions and updates.

Benefits all around

After we introduced the transition summary at my institution, we found that the average initial patient visit with the new adult-care provider decreased by 12 minutes (with a range of 6-19 min). The adult-care providers welcomed receiving such detailed, important patient information packaged in a concise and readily accessible format. It helped them identify the preceding care team members, which facilitated continuity of care, and it also helped them forge a better therapeutic relationship with the patient earlier on in their engagement.

We also learned that patients were more comfortable with the transition, and the referring providers were relieved and reassured that their patients would continue to receive personalized care with the new adult-care provider.

At a personal level, I found I was less stressed as I could spend better-quality clinical time with patients. And I got to eliminate those unwieldy stacks of medical records since getting buy-in from divisional and IT leadership enabled us to automate the entire process of information transfer.

It is important to note that the patient has to consent to release of medical records to other institutions.

Setting up the summary

At our clinic, I started out by adapting the transition summary from guidelines provided by the Endocrine Society to make a template. Then, in collaboration with my pediatric colleagues, I removed and added information so that the revised document would contain information that is vitally important and not readily available in the chart and would be feasible to fill out. For example, we included details such as the patient’s psychosocial history, an estimation of the patient barriers to diabetes management, family relationship issues, and the patient’s reasons for not adopting advanced diabetes technology (see accompanying example of a transition summary) .

I kept the summary brief, at two pages, and piloted it with referring providers who were interested in using the summary and with related supporting services. I also sought buy-in from my institution. This meant that I needed pediatric and adult divisional leadership support, which offered me information technology, resources, and expertise to automate the summary within the electronic health record. Once I had feedback from would-be users, we revised and updated the summary. We set up training for staff, including pediatric providers, nurse practitioners, social workers, and nurses who could fill out the summary, and ultimately succeeded in making it mandatory that the adult-care provider receive a summary before scheduling or seeing the transfer patient.

I started out with a paper version, and once we’d refined the questions, we incorporated it into the electronic medical record.

The information we use in our summary is grouped under the following headings:

- Reason for transition.

- Diabetes type.

- Degree of diabetes control.

- Type of insulin therapy and supplies.

- Current and former insulin regimen: reasons for discontinuation of any therapies or reluctance to start any therapies.

- Diabetes health maintenance.

- Social history and support, including living situation, main social support network, child protective services involvement.

- Other pertinent medical surgical history, including psychiatric disease.

Tips and takeaways

Top of the list of takeaways is that you should make the final document work for you, your colleagues, and ultimately, your patients – customize it as you see fit, but be sure to keep it short and easy to fill out. Make a note as you start using it in practice of what you think might be missing from the chart and whether updates are needed. If you can, it’s a great idea to fold the transfer summary into the electronic medical record, though it’s not imperative. Care coordination is key to successful transfer of patients, whether from pediatric to adult care or hospital to home. A small change to work flow can result in a huge change in patient and provider satisfaction, as well as a reduction in visit times.

Dr. Agarwal is director of the Supporting Emerging Adults With Diabetes (SEAD) program at Montefiore Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York. She reports no disclosures or financial conflicts of interest. Write to her at cenews@mdedge.com.

Diabetes is a complex disease with a range of nuanced therapy options and a plethora of risk factors that could significantly affect patient quality of life and long-term outcomes. From the outset, after diagnosis, a selected regimen has to be meticulously tailored to a patient’s clinical needs and monitored over time, and many other nonclinical variables, such as patient preference, social history, access to care, and support systems, as well as the cost of the drugs and its impact on the patient, must also be considered.

The increase in the incidence of youth-onset diabetes means that more young adults are making the transition from pediatric to adult care, and careful care coordination is paramount at the handover point to ensure that a full and complete account of the history gets transferred to the adult-care provider.

So how do you distill the information from all those records (on paper and online) that you’ve accumulated during the time you’ve been treating a young adult who is now transitioning to adult care?

Transition summary

One resource that can facilitate this handover is the transition summary. It effectively consolidates and packages the aforementioned aspects of care and patient history so that the adult-care provider does not have to collect the patient’s history from the start. The transition summary should not be confused with the discharge or medical summary, which focuses only on the preceding clinical care.

It is important to stress at this stage that collaboration between the pediatric- and adult-care providers is crucial to the success of such a summary, from its creation, to its implementation, and through the subsequent and inevitable revisions and updates.

Benefits all around

After we introduced the transition summary at my institution, we found that the average initial patient visit with the new adult-care provider decreased by 12 minutes (with a range of 6-19 min). The adult-care providers welcomed receiving such detailed, important patient information packaged in a concise and readily accessible format. It helped them identify the preceding care team members, which facilitated continuity of care, and it also helped them forge a better therapeutic relationship with the patient earlier on in their engagement.

We also learned that patients were more comfortable with the transition, and the referring providers were relieved and reassured that their patients would continue to receive personalized care with the new adult-care provider.

At a personal level, I found I was less stressed as I could spend better-quality clinical time with patients. And I got to eliminate those unwieldy stacks of medical records since getting buy-in from divisional and IT leadership enabled us to automate the entire process of information transfer.

It is important to note that the patient has to consent to release of medical records to other institutions.

Setting up the summary

At our clinic, I started out by adapting the transition summary from guidelines provided by the Endocrine Society to make a template. Then, in collaboration with my pediatric colleagues, I removed and added information so that the revised document would contain information that is vitally important and not readily available in the chart and would be feasible to fill out. For example, we included details such as the patient’s psychosocial history, an estimation of the patient barriers to diabetes management, family relationship issues, and the patient’s reasons for not adopting advanced diabetes technology (see accompanying example of a transition summary) .

I kept the summary brief, at two pages, and piloted it with referring providers who were interested in using the summary and with related supporting services. I also sought buy-in from my institution. This meant that I needed pediatric and adult divisional leadership support, which offered me information technology, resources, and expertise to automate the summary within the electronic health record. Once I had feedback from would-be users, we revised and updated the summary. We set up training for staff, including pediatric providers, nurse practitioners, social workers, and nurses who could fill out the summary, and ultimately succeeded in making it mandatory that the adult-care provider receive a summary before scheduling or seeing the transfer patient.

I started out with a paper version, and once we’d refined the questions, we incorporated it into the electronic medical record.

The information we use in our summary is grouped under the following headings:

- Reason for transition.

- Diabetes type.

- Degree of diabetes control.

- Type of insulin therapy and supplies.

- Current and former insulin regimen: reasons for discontinuation of any therapies or reluctance to start any therapies.

- Diabetes health maintenance.

- Social history and support, including living situation, main social support network, child protective services involvement.

- Other pertinent medical surgical history, including psychiatric disease.

Tips and takeaways

Top of the list of takeaways is that you should make the final document work for you, your colleagues, and ultimately, your patients – customize it as you see fit, but be sure to keep it short and easy to fill out. Make a note as you start using it in practice of what you think might be missing from the chart and whether updates are needed. If you can, it’s a great idea to fold the transfer summary into the electronic medical record, though it’s not imperative. Care coordination is key to successful transfer of patients, whether from pediatric to adult care or hospital to home. A small change to work flow can result in a huge change in patient and provider satisfaction, as well as a reduction in visit times.

Dr. Agarwal is director of the Supporting Emerging Adults With Diabetes (SEAD) program at Montefiore Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York. She reports no disclosures or financial conflicts of interest. Write to her at cenews@mdedge.com.