User login

The SDM 3 Circle Model: A Literature Synthesis and Adaptation for Shared Decision Making in the Hospital

Evolving models of medical care emphasize the importance of shared decision-making (SDM) on practical and ethical grounds.1-3 SDM is a cognitive, emotional, and relational process in which provider and patient collaborate in a decision after discussing the options, evidence, and potential benefits and harms, while considering the patient’s values, preferences, and circumstances.4 Categories of decisions include information gathering, pharmacotherapy, therapeutic procedures, consultations and referrals, counseling and precautions (eg, behavior modification, goals of care, end-of-life care), and care transitions (eg, transfer or discharge to home).5 Decisions span the continuum of urgency and may be anticipatory or reactive.6 The patient’s environment7,8 and the provider-patient relationship9 have been explicitly incorporated into the ideal SDM process.

SDM has been conceptually and empirically linked with evidence-based practice,1 although the relationship between SDM and clinical outcomes is less clear.10,11 SDM is desired by patients12 and may bolster patient satisfaction, trust, and adherence.13,14 Limited evidence suggests SDM could reduce inappropriate treatments and testing,15 decrease adverse events,16 and promote greater patient safety,17-19 but more well-designed studies are needed.

Provider, patient, and contextual factors influence the extent to which SDM occurs. Providers commonly cite time constraints and perceived lack of applicability to certain clinical scenarios or settings.19 Providers may also lack training and competency in SDM skills.2 Patients may be reluctant to disagree with their provider or fear being mislabeled as “difficult.”20 When faced with high stakes or emotionally charged decisions, patients’ surrogates may prefer to have the provider serve as the sole decision-maker.21 Contextually, there may be limited evidence, high clinical stake, or a number of equally beneficial (or harmful) options.22,23

Current SDM models guide clinicians in determining when and how to engage in SDM, yet models vary widely. For example, Elwyn’s model emphasizes the ethical imperative for SDM and outlines 3 SDM steps: introduce choice, describe options, and help patients explore preferences and make decisions.3 Using a multimodal review and clinician-driven feedback, Legaré’s “IP-SDM” (Interprofessional Shared Decision Making) model illustrates the roles of the interprofessional team and emphasizes the influence of environmental factors on decision-making.24 Recent systematic reviews of SDM models have attempted to identify common elements, language, and processes.2,25,26

This study reviews leading SDM models to construct a more environmentally and contextually sensitive model that is appropriate for the hospital setting. Although developed with hospital medicine in mind, a synthesized model that attends to environmental and systems context, provider/team factors, patient factors, and disease/medical variables is highly relevant in any setting where SDM occurs.

METHODS

We constructed a model that is appropriate for SDM across the care continuum through the following 3-part, iterative group process: (1) a comprehensive literature review of existing SDM models, (2) synthesis and inductive development of a new draft model, and (3) modification of the new model using feedback from SDM experts.

Narrative Literature Review

We performed a structured, comprehensive literature review 29 to compare and contrast existing SDM models and frameworks. Leading models and key concepts were first identified using 2 systematic reviews 25,26 and a comprehensive review.2 In order to extend the search to 2016 and include any overlooked articles, a PubMed search was performed using the terms “shared decision-making” or “medical decision-making” AND “model” or “theory” or “framework” for English-language articles from inception to 2016. The search was repeated using Google Scholar to verify results and obtain the number of citations per article as a proxy for impact and saturation. In order to minimize possible search error or selection bias, reference lists in high-impact publications were hand searched to identify additional articles. All abstracts were manually reviewed by 2 independent authors for relevance and later inclusion in our group iterative process. A priori inclusion criteria were limited to provider-patient SDM (ie, not clinical reasoning or making decisions in general) and complete descriptions of a conceptual model or framework. Additional publications suggested by experts (eg, perspective pieces or terminology summaries) were also reviewed.

Model Development and Expert Review

The draft model and a standardized set of questions (supplementary Appendix A) were then emailed to all first and last authors of the reviewed studies (Table 2). Expert responses were compiled, coded, and analyzed independently by 3 coauthors. Inductive coding techniques and a constant comparative approach were used to code the qualitative data.32 Preliminary findings were shared among the 3 reviewers and discussed until consensus was reached on emerging themes and implications for the new SDM model and multistep SDM pathway. A master list of suggested revisions was shared with the larger authorship team and the model was refined accordingly.

RESULTS

Two previously published systematic reviews25,26 identified 494 articles, 161 conceptual definitions of SDM, and over 30 separate key concepts. The additional PubMed search garnered 1957 publications (with many overlapping from the systematic reviews). A manual search of the systematic reviews and PubMed abstracts identified 16 unique and complete decision-making models for further review. Hand searches of their citations yielded an additional 6 models for a total of 22 models.3,4,13,23,33-51 The majority of excluded articles described specific decision aids and small clinical studies, focused on only one step of the decision-making process, or were not otherwise relevant. The first (SR) and senior authors (JS) reviewed the 22 models for SDM relevance, generalizability, and content saturation, yielding a final sample of 9 SDM models. A subsequent Google Scholar search did not identify any new SDM models but 2 SDM theory papers1,52 and 2 commentaries53,54 were selected based on influence (ie, number of citations), expert recommendation, or coverage of a novel aspect of SDM. A total of 15 studies (9 SDM models + 6 reviews; Table 2) were used by our development team to create a synthesized SDM model. A 10th SDM model55 and 3 additional descriptive and normative studies8,56,57 were later added based on expert feedback and incorporated into our final SDM 3 Circle Model.

Expert Feedback

Twenty-one of 27 (78%) SDM expert authors responded to our e-mail request for feedback. The majority (62%) agreed with the basic elements of the model, including the environmental frame and the 3 domains. Some respondents viewed SDM as strictly a process between patient and provider independent of the disease, leading to refinement of the medical context category. Several experts emphasized the importance of SDM “set-up,” which includes the elicitation of patient preferences in how decisions are made and the extent of patient and/or surrogate involvement.

Several respondents identified time constraints (N = 2), acuity of disease (N = 3), and presence of multiple teams (N = 6) to be the significant factors distinguishing inpatient from outpatient SDM. For some experts, “team” referred to the interprofessional care team, whereas others referred to it as the collaboration among attending physicians and trainees. Experts noted that although the intensity and frequency of inpatient interactions could promote SDM, higher patient acuity and the urgency of decisions could negatively influence SDM and/or the patient’s ability to participate. Similarly, the presence of other team members may either impede or promote SDM by either contributing to miscommunication or bringing well-trained SDM experts to the bedside. Financial impact on patients and resource constraints were also noted as relevant. All of these elements have been incorporated into the final SDM 3 Circle Model and multistep SDM Pathway (Supplemental Appendix A and B).

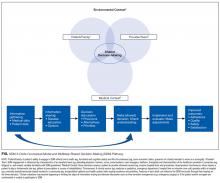

The SDM 3 Circle Model

The SDM 3 Circle Model comprises 3 categories of SDM barriers and facilitators that intersect within the environmental frame of an inpatient ward or other setting: (1) provider/team, (2) patient/family, and (3) medical context. A Venn diagram visually represents the conceptual overlaps and distinctions among these categories that are all affected by the environment in which they occur (Supplemental Appendix A).

The patient/family circle mirrors prior SDM models that address the role of patient preferences in making decisions,3,4,12 with the explicit addition of the roles of families and surrogates as either decision-makers or influencers. This circle includes personal characteristics, such as cognitions (eg, beliefs, attitudes), emotions (eg, anxiety, hope), behaviors (eg, adherence, assertiveness), illness history (ie, subjective experience and understanding of one’s own medical history), and related social features (eg, culture, education, literacy, social supports).

Patient factors are not static over time or context. They occur within an environmental setting and are likely to be influenced by concurrent provider and medical variables (the second and third circles). Disease exacerbation leading to hospitalization or transfer to a subacute facility could dramatically shift the calculus a patient uses to determine preferences or activate dormant family dynamics. Strong provider-patient rapport (the overlap of patient and provider factors) may influence the development of trust and subsequent decisions.9 The type of disease or symptom presentation (circle 3–medical context) may further influence patient factors due to stigma, perceived vulnerability, or assumed prognosis.

The provider/team circle includes both individual and team-based factors falling into similar categories as the patient/family domain, such as cognitions, behavior, and social features; however, these factors include both personal (eg, the provider’s personal history, values, and beliefs) and professional (eg, past medical training, decision-making style, past experiences treating a disease) characteristics. Decisions may involve an interprofessional team representing a broad range of personalities and professional values. Decisions and decision-making processes may change over time as team composition changes, as level of provider expertise varies, or as environmental, patient, or disease/illness factors influence providers and teams.

Medical context includes factors related to the disease and the potential ways to evaluate or manage it. Examples of disease factors include acuity, symptoms, course, and prognosis. Most obviously, disease factors will influence the content of risk-benefit discussions but may also affect the SDM process through disease stigma or cultural assumptions about etiology. Disease evaluation factors include the psychometrics of a diagnostic screen, invasive and noninvasive testing, or a range of different preventive or therapeutic interventions. Treatment variables include the available options, costs, and risk of complications. Medical context variables evolve as evidence-based medicine and biomedical knowledge increase and new treatment options emerge.

Each of the 3 circles operates within the same environmental frame, such as an inpatient medicine ward, which itself operates within a hospital and the broader healthcare system. This frame exerts overt and subtle influences on providers, patients, and even the medical context. Features of the environmental frame include culture (eg, values, preferences, social norms), university versus community setting, incentives, formularies, quality improvement campaigns, regulations, and technology use.

The dynamic interactivity of the environmental frame and the 3 circles inform the process of SDM and highlight key differences that may occur between care settings. Certain features may predominate in different situations, but all will influence and be influenced by features of other circles during the course of SDM.

Application of the SDM 3 Circle Model

Although the SDM process is similar across clinical settings, its operationalization varies in important ways for hospital decision-making. In some situations, patients may defer all decisions to their providers or decisions may be considered with multiple providers concurrently. In the hospital, SDM may not be possible, such as in emergency surgery for an obtunded patient or when the patient and surrogate are not available or able to participate in the decision. Therefore, providers may bypass the steps of information sharing and discussion of the decision (big arrow in the Figure and supplemental

DISCUSSION

The SDM 3 Circle Model provides a concise, ecologically valid, contextually sensitive representation of SDM that synthesizes and extends beyond recent SDM models.3,7,40 Each circle represents the forces that influence SDM across settings. Although the multistep SDM pathway occurs similarly in outpatient and inpatient settings, how each step is operationalized and how each “circle” exerts its influence may differ and warrants further consideration throughout the SDM process. For example, hospitalized patients may have greater stress and anxiety, have more family involvement, be more motivated to adhere to treatment, and may be under greater financial and social pressures. Unlike outpatient primary care, patients are less likely to have an existing relationship with their inpatient providers, potentially compromising patient confidence in the provider, and necessitating expeditious trust building.

The SDM 3 Circle Model captures “setting” in both the broader environmental frame and within the provider/team category of variables. The frame also captures health system and broader community variables that may influence the practicality of some medical decisions. Within this essential frame, all 3 categories of patient, provider, and medical context are included as part of the SDM process. A better understanding of their interplay may be of great value for clinicians, researchers, administrators, and policy makers who wish to further study and promote SDM. Both the SDM 3 Circle Model and its accompanying pathway (Figures 1 and 2) highlight opportunities for intervention and research, and may drive quality improvement initiatives to improve clinical outcomes.

Limitations

We did not perform a new systematic review, potentially omitting lesser-known publications. We mitigated this risk by using recent systematic reviews, searching multiple databases, hand searching citation lists, and making inquiries to SDM experts. Our selection of models used as a foundation for the synthesized model was based on consensus, which included an element of subjective, clinical judgment. Our SDM expert sample was small and limited to authors of the papers we reviewed, potentially restricting the range of viewpoints received. Lastly, the SDM 3 Circle Model highlights key concept areas rather than all possible factors that influence SDM.

CONCLUSIONS

We present a peer-reviewed, literature-based SDM model capable of accounting for the unique circumstances and challenges of SDM in the hospital. The SDM 3 Circle Model identifies the primary categories of variables thought to influence SDM, places them in a shared environmental frame, and visually represents their interactive nature. A multistep representation of the SDM process further illustrates how the unique features and challenges of hospitalization might exert influence at various points as patients and providers reach a shared decision. As the interrelationships of patient and provider/team, medical context, and the environmental frame in which they occur are better understood, more effective and targeted interventions to promote SDM can be developed and evaluated.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Evans Whitaker for his assistance with the literature review and the Patient Engagement Project volunteers for their support and assistance with data collection.

Disclosure

Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from NIH/NCCIH (grant #R25 AT006573, awarded to Dr. Jason Satterfield). The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. The following authors are employed by the sponsor: Stephanie Rennke, MD, Patrick Yuan, BA, Brad Monash, MD, Rebecca Blankenburg, MD, MPH, Ian Chua, MD, Stephanie Harman, MD, Debbie S. Sakai, MD, Joan F. Hilton, DSc, MPH., and Jason Satterfield, PhD.

1. Hoffmann TC, Montori VM, Del Mar C. The connection between evidence-based medicine and shared decision making. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1295-1296. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10186. PubMed

2. Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JC. Shared decision making: Concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(10):1172-1179. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022. PubMed

3. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361-1367. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. PubMed

4. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(5):651-661. PubMed

5. Ofstad EH, Frich JC, Schei E, Frankel RM, Gulbrandsen P. What is a medical decision? A units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(7):915-921. doi:10.1164/rccm.201008-1214OC. PubMed

22. Müller-Engelmann M, Keller H, Donner-Banzhoff N, Krones T. Shared decision making in medicine: The influence of situational treatment factors. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(2):240-246. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.028. PubMed

23. Whitney SN. A New Model of Medical Decisions: Exploring the Limits of Shared Decision Making. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):275-280. doi:10.1177/0272989X03256006. PubMed

24. Légaré F, Bekker H, Desroches S, et al. How can continuing professional development better promote shared decision-making? Perspectives from an international collaboration. Implement Sci. 2011;6:68. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-68. PubMed

25. Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301-312. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. PubMed

26. Moumjid N, Gafni A, Brémond A, Carrère MO. Shared decision making in the medical taxonomy based on physician statements in hospital encounters: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010098. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010098. PubMed

6. Fowler FJ, Levin CA, Sepucha KR. Informing and involving patients to improve the quality of medical decisions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):699-706. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0003. PubMed

7. Weiner SJ, Kelly B, Ashley N, et al. Content coding for contextualization of care: evaluating physician performance at patient-centered decision making. Med Decis Making. 2014;34(1):97-106. doi:10.1177/0272989X13493146. PubMed

8. Weiner SJ, Schwartz A, Sharma G, et al. Patient-centered decision making and health care outcomes: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):573-579. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00001. PubMed

9. Matthias MS, Salyers MP, Frankel RM. Re-thinking shared decision-making: context matters. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(2):176-179. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.01.006 PubMed

10. Clayman ML, Bylund CL, Chewning B, Makoul G. The Impact of Patient Participation in Health Decisions Within Medical Encounters: A Systematic Review. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(4):427-452. doi:10.1177/0272989X15613530. PubMed

11. Shay LA, Lafata JE. Understanding patient perceptions of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):295-301. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.017. PubMed

12. Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9-18. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004. PubMed

13. Butterworth JE, Campbell JL. Older patients and their GPs: shared decision making in enhancing trust. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(628):e709-e718. doi:10.3399/bjgp14X682297. PubMed

14. Joosten EA, DeFuentes-Merillas L, de Weert GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CP, de Jong CA. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(4):219-226. doi:10.1159/000126073. PubMed

15. Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD001431. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. PubMed

16. Weingart SN, Zhu J, Chiappetta L, et al. Hospitalized patients’ participation and its impact on quality of care and patient safety. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(3):269-277. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzr002. PubMed

17. Mohammed K, Nolan MB, Rajjo T, et al. Creating a Patient-Centered Health Care Delivery System: A Systematic Review of Health Care Quality From the Patient Perspective. Am J Med Qual. 2014;31(1):12-21. doi:10.1177/1062860614545124. PubMed

18. Berger Z, Flickinger TE, Pfoh E, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce adverse events in acute care settings: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):548-555. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001769. PubMed

19. Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):526-535. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.018. PubMed

20. Frosch DL, May SG, Rendle KAS, Tietbohl C, Elwyn G. Authoritarian physicians and patients’ fear of being labeled “difficult” among key obstacles to shared decision making. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(5):1030-1038. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0576. PubMed

21. Johnson SK, Bautista CA, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, White DB. An empirical study of surrogates’ preferred level of control over value-laden life support decisions in intensive care encounter: are we all talking about the same thing? Med Decis Making. 2007;27(5):539-546. doi:10.1177/0272989X07306779. PubMed

27. Hallström I, Elander G. Decision-making during hospitalization: parents’ and children’s involvement. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(3):367-375. PubMed

28. Ofstad EH, Frich JC, Schei E, Frankel RM, Gulbrandsen P. Temporal characteristics of decisions in hospital encounters: a threshold for shared decision making? A qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(2):216-222. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.08.005. PubMed

29. Baumeister RF, Leary MR. Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev Gen Psychol. 1997;1(3):311.

30. Moody DL. Theoretical and practical issues in evaluating the quality of conceptual models: current state and future directions. Data Knowl Eng. 2005;55(3):243-276. doi:10.1016/j.datak.2004.12.005.

31. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351-377. PubMed

32. Basics of Qualitative Research | SAGE Publications Inc. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/basics-of-qualitative-research/book235578. Accessed on September 13, 2016. PubMed

33. 2013;2(4):421-433. doi:10.2217/cer.13.46.J Comp Eff Res33. Halley MC, Rendle KA, Frosch DL. A conceptual model of the multiple stages of communication necessary to support patient-centered care. PubMed

34. 2012;87(1):54-61. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.027.Patient Educ Couns34. Torke AM, Petronio S, Sachs GA, Helft PR, Purnell C. A conceptual model of the role of communication in surrogate decision making for hospitalized adults. PubMed

35. 2009;15(6):1142-1151. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01315.x.J Eval Clin Pract35. Falzer PR, Garman MD. A conditional model of evidence-based decision making: Model of evidence-based decision making. PubMed

36. 2012;8(4):161-164. doi:10.1097/PTS.0b013e318267c56e.J Patient Saf36. Holzmueller CG, Wu AW, Pronovost PJ. A framework for encouraging patient engagement in medical decision making. PubMed

37. 2014;97(2):158-164. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.027.Patient Educ Couns37. Elwyn G, Lloyd A, May C, et al. Collaborative deliberation: a model for patient care. PubMed

38. 2002;35(5-6):313-321. doi:10.1016/S1532-0464(03)00037-6.J Biomed Inform38. Ruland CM, Bakken S. Developing, implementing, and evaluating decision support systems for shared decision making in patient care: a conceptual model and case illustration. PubMed

39. 1999;319(7212):764.BMJ39. Shepperd S, Charnock D, Gann B. Helping patients access high quality health information. PubMed

40. 2011;25(1):18-25. doi:10.3109/13561820.2010.490502.J Interprof Care40. Légaré F, Stacey D, Pouliot S, et al. Interprofessionalism and shared decision-making in primary care: a stepwise approach towards a new model. PubMed

41. 2015;25(1):141-152. doi:10.1007/s10926-014-9532-7.J Occup Rehabil41. Coutu MF, Légaré F, Durand MJ, et al. Operationalizing a Shared Decision Making Model for Work Rehabilitation Programs: A Consensus Process. PubMed

42. 2013;13:231.BMC Health Serv Res42. Hölzel LP, Kriston L, Härter M. Patient preference for involvement, experienced involvement, decisional conflict, and satisfaction with physician: a structural equation model test. PubMed

43. 2008;134(4):835-843. doi:10.1378/chest.08-0235.Chest43. Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. PubMed

44. 2013;8:29-36. doi:10.4137/IMI.S12783.Integr Med Insights44. Brooks AT, Silverman L, Wallen G. Shared Decision Making: A Fundamental Tenet in a Conceptual Framework of Integrative Healthcare Delivery. PubMed

45. 2013;33(1):37-47. doi:10.1177/0272989X12458159.Med Decis Making45. Müller-Engelmann M, Donner-Banzhoff N, Keller H, et al. When decisions should be shared: a study of social norms in medical decision making using a factorial survey approach. PubMed

46. 2007;101(4):205-211.Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich46. Mccaffery KJ, Shepherd HL, Trevena L, et al. Shared decision-making in Australia. PubMed

47. 2014;20(2):311-318. doi:10.1007/s12028-013-9922-2.Neurocrit Care

47. Rubin MA. The Collaborative Autonomy Model of Medical Decision-Making. 48. 2013;70(1 Suppl):141S-158S. doi:10.1177/1077558712461952.Med Care Res Rev PubMed

48. McCullough LB. The professional medical ethics model of decision making under conditions of clinical uncertainty. PubMed

49. 2009;87(2):368–390.Milbank Q49. Satterfield JM, Spring B, Brownson RC, et al. Toward a Transdisciplinary Model of Evidence-Based Practice. PubMed

50. 2015;25(3):276-282. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2015.02.002.Womens Health Issues50. Moore JE, Titler MG, Kane Low L, Dalton VK, Sampselle CM. Transforming Patient-Centered Care: Development of the Evidence Informed Decision Making through Engagement Model. PubMed

51. 1997;44(5):681-692.Soc Sci Med51. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). PubMed

52. 2010;80(2):164-172. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.015.Patient Educ Couns52. Stacey D, Légaré F, Pouliot S, Kryworuchko J, Dunn S. Shared decision making models to inform an interprofessional perspective on decision making: a theory analysis. PubMed

53. 2013;70(1 Suppl):94S-112S. doi:10.1177/1077558712459216.Med Care Res Rev53. Epstein RM, Gramling RE. What is shared in shared decision making? Complex decisions when the evidence is unclear. PubMed

54. 2010;304(8):903-904. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1208.JAMA54. Kon AA. The shared decision-making continuum. PubMed

55. 2008;30(3):429-444. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01064.x.Sociol Health Illn55. Rapley T. Distributed decision making: the anatomy of decisions-in-action. PubMed

56. 1997;12(6):339-345.J Gen Intern Med56. Braddock CH 3rd, Fihn SD, Levinson W, Jonsen AR, Pearlman RA. How doctors and patients discuss routine clinical decisions. Informed decision making in the outpatient setting. PubMed

57. 1999;282(24):2313-2320.JAMA57. Braddock CH 3rd, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. PubMed

58. 2009;69(12):1805-1812. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.056.Soc Sci Med58. Smith SK, Dixon A, Trevena L, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ. Exploring patient involvement in healthcare decision making across different education and functional health literacy groups.

2006;9(4):321-332. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00404.x.Health Expect. PubMed

59. Towle A, Godolphin W, Grams G, Lamarre A. Putting informed and shared decision making into practice. PubMed

60. 2011;17(4):554-564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01515.x.J Eval Clin Pract60. Légaré F, Stacey D, Gagnon S, et al. Validating a conceptual model for an interprofessional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study. PubMed

Evolving models of medical care emphasize the importance of shared decision-making (SDM) on practical and ethical grounds.1-3 SDM is a cognitive, emotional, and relational process in which provider and patient collaborate in a decision after discussing the options, evidence, and potential benefits and harms, while considering the patient’s values, preferences, and circumstances.4 Categories of decisions include information gathering, pharmacotherapy, therapeutic procedures, consultations and referrals, counseling and precautions (eg, behavior modification, goals of care, end-of-life care), and care transitions (eg, transfer or discharge to home).5 Decisions span the continuum of urgency and may be anticipatory or reactive.6 The patient’s environment7,8 and the provider-patient relationship9 have been explicitly incorporated into the ideal SDM process.

SDM has been conceptually and empirically linked with evidence-based practice,1 although the relationship between SDM and clinical outcomes is less clear.10,11 SDM is desired by patients12 and may bolster patient satisfaction, trust, and adherence.13,14 Limited evidence suggests SDM could reduce inappropriate treatments and testing,15 decrease adverse events,16 and promote greater patient safety,17-19 but more well-designed studies are needed.

Provider, patient, and contextual factors influence the extent to which SDM occurs. Providers commonly cite time constraints and perceived lack of applicability to certain clinical scenarios or settings.19 Providers may also lack training and competency in SDM skills.2 Patients may be reluctant to disagree with their provider or fear being mislabeled as “difficult.”20 When faced with high stakes or emotionally charged decisions, patients’ surrogates may prefer to have the provider serve as the sole decision-maker.21 Contextually, there may be limited evidence, high clinical stake, or a number of equally beneficial (or harmful) options.22,23

Current SDM models guide clinicians in determining when and how to engage in SDM, yet models vary widely. For example, Elwyn’s model emphasizes the ethical imperative for SDM and outlines 3 SDM steps: introduce choice, describe options, and help patients explore preferences and make decisions.3 Using a multimodal review and clinician-driven feedback, Legaré’s “IP-SDM” (Interprofessional Shared Decision Making) model illustrates the roles of the interprofessional team and emphasizes the influence of environmental factors on decision-making.24 Recent systematic reviews of SDM models have attempted to identify common elements, language, and processes.2,25,26

This study reviews leading SDM models to construct a more environmentally and contextually sensitive model that is appropriate for the hospital setting. Although developed with hospital medicine in mind, a synthesized model that attends to environmental and systems context, provider/team factors, patient factors, and disease/medical variables is highly relevant in any setting where SDM occurs.

METHODS

We constructed a model that is appropriate for SDM across the care continuum through the following 3-part, iterative group process: (1) a comprehensive literature review of existing SDM models, (2) synthesis and inductive development of a new draft model, and (3) modification of the new model using feedback from SDM experts.

Narrative Literature Review

We performed a structured, comprehensive literature review 29 to compare and contrast existing SDM models and frameworks. Leading models and key concepts were first identified using 2 systematic reviews 25,26 and a comprehensive review.2 In order to extend the search to 2016 and include any overlooked articles, a PubMed search was performed using the terms “shared decision-making” or “medical decision-making” AND “model” or “theory” or “framework” for English-language articles from inception to 2016. The search was repeated using Google Scholar to verify results and obtain the number of citations per article as a proxy for impact and saturation. In order to minimize possible search error or selection bias, reference lists in high-impact publications were hand searched to identify additional articles. All abstracts were manually reviewed by 2 independent authors for relevance and later inclusion in our group iterative process. A priori inclusion criteria were limited to provider-patient SDM (ie, not clinical reasoning or making decisions in general) and complete descriptions of a conceptual model or framework. Additional publications suggested by experts (eg, perspective pieces or terminology summaries) were also reviewed.

Model Development and Expert Review

The draft model and a standardized set of questions (supplementary Appendix A) were then emailed to all first and last authors of the reviewed studies (Table 2). Expert responses were compiled, coded, and analyzed independently by 3 coauthors. Inductive coding techniques and a constant comparative approach were used to code the qualitative data.32 Preliminary findings were shared among the 3 reviewers and discussed until consensus was reached on emerging themes and implications for the new SDM model and multistep SDM pathway. A master list of suggested revisions was shared with the larger authorship team and the model was refined accordingly.

RESULTS

Two previously published systematic reviews25,26 identified 494 articles, 161 conceptual definitions of SDM, and over 30 separate key concepts. The additional PubMed search garnered 1957 publications (with many overlapping from the systematic reviews). A manual search of the systematic reviews and PubMed abstracts identified 16 unique and complete decision-making models for further review. Hand searches of their citations yielded an additional 6 models for a total of 22 models.3,4,13,23,33-51 The majority of excluded articles described specific decision aids and small clinical studies, focused on only one step of the decision-making process, or were not otherwise relevant. The first (SR) and senior authors (JS) reviewed the 22 models for SDM relevance, generalizability, and content saturation, yielding a final sample of 9 SDM models. A subsequent Google Scholar search did not identify any new SDM models but 2 SDM theory papers1,52 and 2 commentaries53,54 were selected based on influence (ie, number of citations), expert recommendation, or coverage of a novel aspect of SDM. A total of 15 studies (9 SDM models + 6 reviews; Table 2) were used by our development team to create a synthesized SDM model. A 10th SDM model55 and 3 additional descriptive and normative studies8,56,57 were later added based on expert feedback and incorporated into our final SDM 3 Circle Model.

Expert Feedback

Twenty-one of 27 (78%) SDM expert authors responded to our e-mail request for feedback. The majority (62%) agreed with the basic elements of the model, including the environmental frame and the 3 domains. Some respondents viewed SDM as strictly a process between patient and provider independent of the disease, leading to refinement of the medical context category. Several experts emphasized the importance of SDM “set-up,” which includes the elicitation of patient preferences in how decisions are made and the extent of patient and/or surrogate involvement.

Several respondents identified time constraints (N = 2), acuity of disease (N = 3), and presence of multiple teams (N = 6) to be the significant factors distinguishing inpatient from outpatient SDM. For some experts, “team” referred to the interprofessional care team, whereas others referred to it as the collaboration among attending physicians and trainees. Experts noted that although the intensity and frequency of inpatient interactions could promote SDM, higher patient acuity and the urgency of decisions could negatively influence SDM and/or the patient’s ability to participate. Similarly, the presence of other team members may either impede or promote SDM by either contributing to miscommunication or bringing well-trained SDM experts to the bedside. Financial impact on patients and resource constraints were also noted as relevant. All of these elements have been incorporated into the final SDM 3 Circle Model and multistep SDM Pathway (Supplemental Appendix A and B).

The SDM 3 Circle Model

The SDM 3 Circle Model comprises 3 categories of SDM barriers and facilitators that intersect within the environmental frame of an inpatient ward or other setting: (1) provider/team, (2) patient/family, and (3) medical context. A Venn diagram visually represents the conceptual overlaps and distinctions among these categories that are all affected by the environment in which they occur (Supplemental Appendix A).

The patient/family circle mirrors prior SDM models that address the role of patient preferences in making decisions,3,4,12 with the explicit addition of the roles of families and surrogates as either decision-makers or influencers. This circle includes personal characteristics, such as cognitions (eg, beliefs, attitudes), emotions (eg, anxiety, hope), behaviors (eg, adherence, assertiveness), illness history (ie, subjective experience and understanding of one’s own medical history), and related social features (eg, culture, education, literacy, social supports).

Patient factors are not static over time or context. They occur within an environmental setting and are likely to be influenced by concurrent provider and medical variables (the second and third circles). Disease exacerbation leading to hospitalization or transfer to a subacute facility could dramatically shift the calculus a patient uses to determine preferences or activate dormant family dynamics. Strong provider-patient rapport (the overlap of patient and provider factors) may influence the development of trust and subsequent decisions.9 The type of disease or symptom presentation (circle 3–medical context) may further influence patient factors due to stigma, perceived vulnerability, or assumed prognosis.

The provider/team circle includes both individual and team-based factors falling into similar categories as the patient/family domain, such as cognitions, behavior, and social features; however, these factors include both personal (eg, the provider’s personal history, values, and beliefs) and professional (eg, past medical training, decision-making style, past experiences treating a disease) characteristics. Decisions may involve an interprofessional team representing a broad range of personalities and professional values. Decisions and decision-making processes may change over time as team composition changes, as level of provider expertise varies, or as environmental, patient, or disease/illness factors influence providers and teams.

Medical context includes factors related to the disease and the potential ways to evaluate or manage it. Examples of disease factors include acuity, symptoms, course, and prognosis. Most obviously, disease factors will influence the content of risk-benefit discussions but may also affect the SDM process through disease stigma or cultural assumptions about etiology. Disease evaluation factors include the psychometrics of a diagnostic screen, invasive and noninvasive testing, or a range of different preventive or therapeutic interventions. Treatment variables include the available options, costs, and risk of complications. Medical context variables evolve as evidence-based medicine and biomedical knowledge increase and new treatment options emerge.

Each of the 3 circles operates within the same environmental frame, such as an inpatient medicine ward, which itself operates within a hospital and the broader healthcare system. This frame exerts overt and subtle influences on providers, patients, and even the medical context. Features of the environmental frame include culture (eg, values, preferences, social norms), university versus community setting, incentives, formularies, quality improvement campaigns, regulations, and technology use.

The dynamic interactivity of the environmental frame and the 3 circles inform the process of SDM and highlight key differences that may occur between care settings. Certain features may predominate in different situations, but all will influence and be influenced by features of other circles during the course of SDM.

Application of the SDM 3 Circle Model

Although the SDM process is similar across clinical settings, its operationalization varies in important ways for hospital decision-making. In some situations, patients may defer all decisions to their providers or decisions may be considered with multiple providers concurrently. In the hospital, SDM may not be possible, such as in emergency surgery for an obtunded patient or when the patient and surrogate are not available or able to participate in the decision. Therefore, providers may bypass the steps of information sharing and discussion of the decision (big arrow in the Figure and supplemental

DISCUSSION

The SDM 3 Circle Model provides a concise, ecologically valid, contextually sensitive representation of SDM that synthesizes and extends beyond recent SDM models.3,7,40 Each circle represents the forces that influence SDM across settings. Although the multistep SDM pathway occurs similarly in outpatient and inpatient settings, how each step is operationalized and how each “circle” exerts its influence may differ and warrants further consideration throughout the SDM process. For example, hospitalized patients may have greater stress and anxiety, have more family involvement, be more motivated to adhere to treatment, and may be under greater financial and social pressures. Unlike outpatient primary care, patients are less likely to have an existing relationship with their inpatient providers, potentially compromising patient confidence in the provider, and necessitating expeditious trust building.

The SDM 3 Circle Model captures “setting” in both the broader environmental frame and within the provider/team category of variables. The frame also captures health system and broader community variables that may influence the practicality of some medical decisions. Within this essential frame, all 3 categories of patient, provider, and medical context are included as part of the SDM process. A better understanding of their interplay may be of great value for clinicians, researchers, administrators, and policy makers who wish to further study and promote SDM. Both the SDM 3 Circle Model and its accompanying pathway (Figures 1 and 2) highlight opportunities for intervention and research, and may drive quality improvement initiatives to improve clinical outcomes.

Limitations

We did not perform a new systematic review, potentially omitting lesser-known publications. We mitigated this risk by using recent systematic reviews, searching multiple databases, hand searching citation lists, and making inquiries to SDM experts. Our selection of models used as a foundation for the synthesized model was based on consensus, which included an element of subjective, clinical judgment. Our SDM expert sample was small and limited to authors of the papers we reviewed, potentially restricting the range of viewpoints received. Lastly, the SDM 3 Circle Model highlights key concept areas rather than all possible factors that influence SDM.

CONCLUSIONS

We present a peer-reviewed, literature-based SDM model capable of accounting for the unique circumstances and challenges of SDM in the hospital. The SDM 3 Circle Model identifies the primary categories of variables thought to influence SDM, places them in a shared environmental frame, and visually represents their interactive nature. A multistep representation of the SDM process further illustrates how the unique features and challenges of hospitalization might exert influence at various points as patients and providers reach a shared decision. As the interrelationships of patient and provider/team, medical context, and the environmental frame in which they occur are better understood, more effective and targeted interventions to promote SDM can be developed and evaluated.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Evans Whitaker for his assistance with the literature review and the Patient Engagement Project volunteers for their support and assistance with data collection.

Disclosure

Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from NIH/NCCIH (grant #R25 AT006573, awarded to Dr. Jason Satterfield). The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. The following authors are employed by the sponsor: Stephanie Rennke, MD, Patrick Yuan, BA, Brad Monash, MD, Rebecca Blankenburg, MD, MPH, Ian Chua, MD, Stephanie Harman, MD, Debbie S. Sakai, MD, Joan F. Hilton, DSc, MPH., and Jason Satterfield, PhD.

Evolving models of medical care emphasize the importance of shared decision-making (SDM) on practical and ethical grounds.1-3 SDM is a cognitive, emotional, and relational process in which provider and patient collaborate in a decision after discussing the options, evidence, and potential benefits and harms, while considering the patient’s values, preferences, and circumstances.4 Categories of decisions include information gathering, pharmacotherapy, therapeutic procedures, consultations and referrals, counseling and precautions (eg, behavior modification, goals of care, end-of-life care), and care transitions (eg, transfer or discharge to home).5 Decisions span the continuum of urgency and may be anticipatory or reactive.6 The patient’s environment7,8 and the provider-patient relationship9 have been explicitly incorporated into the ideal SDM process.

SDM has been conceptually and empirically linked with evidence-based practice,1 although the relationship between SDM and clinical outcomes is less clear.10,11 SDM is desired by patients12 and may bolster patient satisfaction, trust, and adherence.13,14 Limited evidence suggests SDM could reduce inappropriate treatments and testing,15 decrease adverse events,16 and promote greater patient safety,17-19 but more well-designed studies are needed.

Provider, patient, and contextual factors influence the extent to which SDM occurs. Providers commonly cite time constraints and perceived lack of applicability to certain clinical scenarios or settings.19 Providers may also lack training and competency in SDM skills.2 Patients may be reluctant to disagree with their provider or fear being mislabeled as “difficult.”20 When faced with high stakes or emotionally charged decisions, patients’ surrogates may prefer to have the provider serve as the sole decision-maker.21 Contextually, there may be limited evidence, high clinical stake, or a number of equally beneficial (or harmful) options.22,23

Current SDM models guide clinicians in determining when and how to engage in SDM, yet models vary widely. For example, Elwyn’s model emphasizes the ethical imperative for SDM and outlines 3 SDM steps: introduce choice, describe options, and help patients explore preferences and make decisions.3 Using a multimodal review and clinician-driven feedback, Legaré’s “IP-SDM” (Interprofessional Shared Decision Making) model illustrates the roles of the interprofessional team and emphasizes the influence of environmental factors on decision-making.24 Recent systematic reviews of SDM models have attempted to identify common elements, language, and processes.2,25,26

This study reviews leading SDM models to construct a more environmentally and contextually sensitive model that is appropriate for the hospital setting. Although developed with hospital medicine in mind, a synthesized model that attends to environmental and systems context, provider/team factors, patient factors, and disease/medical variables is highly relevant in any setting where SDM occurs.

METHODS

We constructed a model that is appropriate for SDM across the care continuum through the following 3-part, iterative group process: (1) a comprehensive literature review of existing SDM models, (2) synthesis and inductive development of a new draft model, and (3) modification of the new model using feedback from SDM experts.

Narrative Literature Review

We performed a structured, comprehensive literature review 29 to compare and contrast existing SDM models and frameworks. Leading models and key concepts were first identified using 2 systematic reviews 25,26 and a comprehensive review.2 In order to extend the search to 2016 and include any overlooked articles, a PubMed search was performed using the terms “shared decision-making” or “medical decision-making” AND “model” or “theory” or “framework” for English-language articles from inception to 2016. The search was repeated using Google Scholar to verify results and obtain the number of citations per article as a proxy for impact and saturation. In order to minimize possible search error or selection bias, reference lists in high-impact publications were hand searched to identify additional articles. All abstracts were manually reviewed by 2 independent authors for relevance and later inclusion in our group iterative process. A priori inclusion criteria were limited to provider-patient SDM (ie, not clinical reasoning or making decisions in general) and complete descriptions of a conceptual model or framework. Additional publications suggested by experts (eg, perspective pieces or terminology summaries) were also reviewed.

Model Development and Expert Review

The draft model and a standardized set of questions (supplementary Appendix A) were then emailed to all first and last authors of the reviewed studies (Table 2). Expert responses were compiled, coded, and analyzed independently by 3 coauthors. Inductive coding techniques and a constant comparative approach were used to code the qualitative data.32 Preliminary findings were shared among the 3 reviewers and discussed until consensus was reached on emerging themes and implications for the new SDM model and multistep SDM pathway. A master list of suggested revisions was shared with the larger authorship team and the model was refined accordingly.

RESULTS

Two previously published systematic reviews25,26 identified 494 articles, 161 conceptual definitions of SDM, and over 30 separate key concepts. The additional PubMed search garnered 1957 publications (with many overlapping from the systematic reviews). A manual search of the systematic reviews and PubMed abstracts identified 16 unique and complete decision-making models for further review. Hand searches of their citations yielded an additional 6 models for a total of 22 models.3,4,13,23,33-51 The majority of excluded articles described specific decision aids and small clinical studies, focused on only one step of the decision-making process, or were not otherwise relevant. The first (SR) and senior authors (JS) reviewed the 22 models for SDM relevance, generalizability, and content saturation, yielding a final sample of 9 SDM models. A subsequent Google Scholar search did not identify any new SDM models but 2 SDM theory papers1,52 and 2 commentaries53,54 were selected based on influence (ie, number of citations), expert recommendation, or coverage of a novel aspect of SDM. A total of 15 studies (9 SDM models + 6 reviews; Table 2) were used by our development team to create a synthesized SDM model. A 10th SDM model55 and 3 additional descriptive and normative studies8,56,57 were later added based on expert feedback and incorporated into our final SDM 3 Circle Model.

Expert Feedback

Twenty-one of 27 (78%) SDM expert authors responded to our e-mail request for feedback. The majority (62%) agreed with the basic elements of the model, including the environmental frame and the 3 domains. Some respondents viewed SDM as strictly a process between patient and provider independent of the disease, leading to refinement of the medical context category. Several experts emphasized the importance of SDM “set-up,” which includes the elicitation of patient preferences in how decisions are made and the extent of patient and/or surrogate involvement.

Several respondents identified time constraints (N = 2), acuity of disease (N = 3), and presence of multiple teams (N = 6) to be the significant factors distinguishing inpatient from outpatient SDM. For some experts, “team” referred to the interprofessional care team, whereas others referred to it as the collaboration among attending physicians and trainees. Experts noted that although the intensity and frequency of inpatient interactions could promote SDM, higher patient acuity and the urgency of decisions could negatively influence SDM and/or the patient’s ability to participate. Similarly, the presence of other team members may either impede or promote SDM by either contributing to miscommunication or bringing well-trained SDM experts to the bedside. Financial impact on patients and resource constraints were also noted as relevant. All of these elements have been incorporated into the final SDM 3 Circle Model and multistep SDM Pathway (Supplemental Appendix A and B).

The SDM 3 Circle Model

The SDM 3 Circle Model comprises 3 categories of SDM barriers and facilitators that intersect within the environmental frame of an inpatient ward or other setting: (1) provider/team, (2) patient/family, and (3) medical context. A Venn diagram visually represents the conceptual overlaps and distinctions among these categories that are all affected by the environment in which they occur (Supplemental Appendix A).

The patient/family circle mirrors prior SDM models that address the role of patient preferences in making decisions,3,4,12 with the explicit addition of the roles of families and surrogates as either decision-makers or influencers. This circle includes personal characteristics, such as cognitions (eg, beliefs, attitudes), emotions (eg, anxiety, hope), behaviors (eg, adherence, assertiveness), illness history (ie, subjective experience and understanding of one’s own medical history), and related social features (eg, culture, education, literacy, social supports).

Patient factors are not static over time or context. They occur within an environmental setting and are likely to be influenced by concurrent provider and medical variables (the second and third circles). Disease exacerbation leading to hospitalization or transfer to a subacute facility could dramatically shift the calculus a patient uses to determine preferences or activate dormant family dynamics. Strong provider-patient rapport (the overlap of patient and provider factors) may influence the development of trust and subsequent decisions.9 The type of disease or symptom presentation (circle 3–medical context) may further influence patient factors due to stigma, perceived vulnerability, or assumed prognosis.

The provider/team circle includes both individual and team-based factors falling into similar categories as the patient/family domain, such as cognitions, behavior, and social features; however, these factors include both personal (eg, the provider’s personal history, values, and beliefs) and professional (eg, past medical training, decision-making style, past experiences treating a disease) characteristics. Decisions may involve an interprofessional team representing a broad range of personalities and professional values. Decisions and decision-making processes may change over time as team composition changes, as level of provider expertise varies, or as environmental, patient, or disease/illness factors influence providers and teams.

Medical context includes factors related to the disease and the potential ways to evaluate or manage it. Examples of disease factors include acuity, symptoms, course, and prognosis. Most obviously, disease factors will influence the content of risk-benefit discussions but may also affect the SDM process through disease stigma or cultural assumptions about etiology. Disease evaluation factors include the psychometrics of a diagnostic screen, invasive and noninvasive testing, or a range of different preventive or therapeutic interventions. Treatment variables include the available options, costs, and risk of complications. Medical context variables evolve as evidence-based medicine and biomedical knowledge increase and new treatment options emerge.

Each of the 3 circles operates within the same environmental frame, such as an inpatient medicine ward, which itself operates within a hospital and the broader healthcare system. This frame exerts overt and subtle influences on providers, patients, and even the medical context. Features of the environmental frame include culture (eg, values, preferences, social norms), university versus community setting, incentives, formularies, quality improvement campaigns, regulations, and technology use.

The dynamic interactivity of the environmental frame and the 3 circles inform the process of SDM and highlight key differences that may occur between care settings. Certain features may predominate in different situations, but all will influence and be influenced by features of other circles during the course of SDM.

Application of the SDM 3 Circle Model

Although the SDM process is similar across clinical settings, its operationalization varies in important ways for hospital decision-making. In some situations, patients may defer all decisions to their providers or decisions may be considered with multiple providers concurrently. In the hospital, SDM may not be possible, such as in emergency surgery for an obtunded patient or when the patient and surrogate are not available or able to participate in the decision. Therefore, providers may bypass the steps of information sharing and discussion of the decision (big arrow in the Figure and supplemental

DISCUSSION

The SDM 3 Circle Model provides a concise, ecologically valid, contextually sensitive representation of SDM that synthesizes and extends beyond recent SDM models.3,7,40 Each circle represents the forces that influence SDM across settings. Although the multistep SDM pathway occurs similarly in outpatient and inpatient settings, how each step is operationalized and how each “circle” exerts its influence may differ and warrants further consideration throughout the SDM process. For example, hospitalized patients may have greater stress and anxiety, have more family involvement, be more motivated to adhere to treatment, and may be under greater financial and social pressures. Unlike outpatient primary care, patients are less likely to have an existing relationship with their inpatient providers, potentially compromising patient confidence in the provider, and necessitating expeditious trust building.

The SDM 3 Circle Model captures “setting” in both the broader environmental frame and within the provider/team category of variables. The frame also captures health system and broader community variables that may influence the practicality of some medical decisions. Within this essential frame, all 3 categories of patient, provider, and medical context are included as part of the SDM process. A better understanding of their interplay may be of great value for clinicians, researchers, administrators, and policy makers who wish to further study and promote SDM. Both the SDM 3 Circle Model and its accompanying pathway (Figures 1 and 2) highlight opportunities for intervention and research, and may drive quality improvement initiatives to improve clinical outcomes.

Limitations

We did not perform a new systematic review, potentially omitting lesser-known publications. We mitigated this risk by using recent systematic reviews, searching multiple databases, hand searching citation lists, and making inquiries to SDM experts. Our selection of models used as a foundation for the synthesized model was based on consensus, which included an element of subjective, clinical judgment. Our SDM expert sample was small and limited to authors of the papers we reviewed, potentially restricting the range of viewpoints received. Lastly, the SDM 3 Circle Model highlights key concept areas rather than all possible factors that influence SDM.

CONCLUSIONS

We present a peer-reviewed, literature-based SDM model capable of accounting for the unique circumstances and challenges of SDM in the hospital. The SDM 3 Circle Model identifies the primary categories of variables thought to influence SDM, places them in a shared environmental frame, and visually represents their interactive nature. A multistep representation of the SDM process further illustrates how the unique features and challenges of hospitalization might exert influence at various points as patients and providers reach a shared decision. As the interrelationships of patient and provider/team, medical context, and the environmental frame in which they occur are better understood, more effective and targeted interventions to promote SDM can be developed and evaluated.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Evans Whitaker for his assistance with the literature review and the Patient Engagement Project volunteers for their support and assistance with data collection.

Disclosure

Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from NIH/NCCIH (grant #R25 AT006573, awarded to Dr. Jason Satterfield). The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. The following authors are employed by the sponsor: Stephanie Rennke, MD, Patrick Yuan, BA, Brad Monash, MD, Rebecca Blankenburg, MD, MPH, Ian Chua, MD, Stephanie Harman, MD, Debbie S. Sakai, MD, Joan F. Hilton, DSc, MPH., and Jason Satterfield, PhD.

1. Hoffmann TC, Montori VM, Del Mar C. The connection between evidence-based medicine and shared decision making. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1295-1296. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10186. PubMed

2. Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JC. Shared decision making: Concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(10):1172-1179. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022. PubMed

3. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361-1367. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. PubMed

4. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(5):651-661. PubMed

5. Ofstad EH, Frich JC, Schei E, Frankel RM, Gulbrandsen P. What is a medical decision? A units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(7):915-921. doi:10.1164/rccm.201008-1214OC. PubMed

22. Müller-Engelmann M, Keller H, Donner-Banzhoff N, Krones T. Shared decision making in medicine: The influence of situational treatment factors. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(2):240-246. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.028. PubMed

23. Whitney SN. A New Model of Medical Decisions: Exploring the Limits of Shared Decision Making. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):275-280. doi:10.1177/0272989X03256006. PubMed

24. Légaré F, Bekker H, Desroches S, et al. How can continuing professional development better promote shared decision-making? Perspectives from an international collaboration. Implement Sci. 2011;6:68. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-68. PubMed

25. Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301-312. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. PubMed

26. Moumjid N, Gafni A, Brémond A, Carrère MO. Shared decision making in the medical taxonomy based on physician statements in hospital encounters: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010098. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010098. PubMed

6. Fowler FJ, Levin CA, Sepucha KR. Informing and involving patients to improve the quality of medical decisions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):699-706. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0003. PubMed

7. Weiner SJ, Kelly B, Ashley N, et al. Content coding for contextualization of care: evaluating physician performance at patient-centered decision making. Med Decis Making. 2014;34(1):97-106. doi:10.1177/0272989X13493146. PubMed

8. Weiner SJ, Schwartz A, Sharma G, et al. Patient-centered decision making and health care outcomes: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):573-579. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00001. PubMed

9. Matthias MS, Salyers MP, Frankel RM. Re-thinking shared decision-making: context matters. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(2):176-179. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.01.006 PubMed

10. Clayman ML, Bylund CL, Chewning B, Makoul G. The Impact of Patient Participation in Health Decisions Within Medical Encounters: A Systematic Review. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(4):427-452. doi:10.1177/0272989X15613530. PubMed

11. Shay LA, Lafata JE. Understanding patient perceptions of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):295-301. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.017. PubMed

12. Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9-18. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004. PubMed

13. Butterworth JE, Campbell JL. Older patients and their GPs: shared decision making in enhancing trust. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(628):e709-e718. doi:10.3399/bjgp14X682297. PubMed

14. Joosten EA, DeFuentes-Merillas L, de Weert GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CP, de Jong CA. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(4):219-226. doi:10.1159/000126073. PubMed

15. Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD001431. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. PubMed

16. Weingart SN, Zhu J, Chiappetta L, et al. Hospitalized patients’ participation and its impact on quality of care and patient safety. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(3):269-277. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzr002. PubMed

17. Mohammed K, Nolan MB, Rajjo T, et al. Creating a Patient-Centered Health Care Delivery System: A Systematic Review of Health Care Quality From the Patient Perspective. Am J Med Qual. 2014;31(1):12-21. doi:10.1177/1062860614545124. PubMed

18. Berger Z, Flickinger TE, Pfoh E, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce adverse events in acute care settings: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):548-555. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001769. PubMed

19. Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):526-535. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.018. PubMed

20. Frosch DL, May SG, Rendle KAS, Tietbohl C, Elwyn G. Authoritarian physicians and patients’ fear of being labeled “difficult” among key obstacles to shared decision making. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(5):1030-1038. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0576. PubMed

21. Johnson SK, Bautista CA, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, White DB. An empirical study of surrogates’ preferred level of control over value-laden life support decisions in intensive care encounter: are we all talking about the same thing? Med Decis Making. 2007;27(5):539-546. doi:10.1177/0272989X07306779. PubMed

27. Hallström I, Elander G. Decision-making during hospitalization: parents’ and children’s involvement. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(3):367-375. PubMed

28. Ofstad EH, Frich JC, Schei E, Frankel RM, Gulbrandsen P. Temporal characteristics of decisions in hospital encounters: a threshold for shared decision making? A qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(2):216-222. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.08.005. PubMed

29. Baumeister RF, Leary MR. Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev Gen Psychol. 1997;1(3):311.

30. Moody DL. Theoretical and practical issues in evaluating the quality of conceptual models: current state and future directions. Data Knowl Eng. 2005;55(3):243-276. doi:10.1016/j.datak.2004.12.005.

31. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351-377. PubMed

32. Basics of Qualitative Research | SAGE Publications Inc. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/basics-of-qualitative-research/book235578. Accessed on September 13, 2016. PubMed

33. 2013;2(4):421-433. doi:10.2217/cer.13.46.J Comp Eff Res33. Halley MC, Rendle KA, Frosch DL. A conceptual model of the multiple stages of communication necessary to support patient-centered care. PubMed

34. 2012;87(1):54-61. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.027.Patient Educ Couns34. Torke AM, Petronio S, Sachs GA, Helft PR, Purnell C. A conceptual model of the role of communication in surrogate decision making for hospitalized adults. PubMed

35. 2009;15(6):1142-1151. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01315.x.J Eval Clin Pract35. Falzer PR, Garman MD. A conditional model of evidence-based decision making: Model of evidence-based decision making. PubMed

36. 2012;8(4):161-164. doi:10.1097/PTS.0b013e318267c56e.J Patient Saf36. Holzmueller CG, Wu AW, Pronovost PJ. A framework for encouraging patient engagement in medical decision making. PubMed

37. 2014;97(2):158-164. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.027.Patient Educ Couns37. Elwyn G, Lloyd A, May C, et al. Collaborative deliberation: a model for patient care. PubMed

38. 2002;35(5-6):313-321. doi:10.1016/S1532-0464(03)00037-6.J Biomed Inform38. Ruland CM, Bakken S. Developing, implementing, and evaluating decision support systems for shared decision making in patient care: a conceptual model and case illustration. PubMed

39. 1999;319(7212):764.BMJ39. Shepperd S, Charnock D, Gann B. Helping patients access high quality health information. PubMed

40. 2011;25(1):18-25. doi:10.3109/13561820.2010.490502.J Interprof Care40. Légaré F, Stacey D, Pouliot S, et al. Interprofessionalism and shared decision-making in primary care: a stepwise approach towards a new model. PubMed

41. 2015;25(1):141-152. doi:10.1007/s10926-014-9532-7.J Occup Rehabil41. Coutu MF, Légaré F, Durand MJ, et al. Operationalizing a Shared Decision Making Model for Work Rehabilitation Programs: A Consensus Process. PubMed

42. 2013;13:231.BMC Health Serv Res42. Hölzel LP, Kriston L, Härter M. Patient preference for involvement, experienced involvement, decisional conflict, and satisfaction with physician: a structural equation model test. PubMed

43. 2008;134(4):835-843. doi:10.1378/chest.08-0235.Chest43. Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. PubMed

44. 2013;8:29-36. doi:10.4137/IMI.S12783.Integr Med Insights44. Brooks AT, Silverman L, Wallen G. Shared Decision Making: A Fundamental Tenet in a Conceptual Framework of Integrative Healthcare Delivery. PubMed

45. 2013;33(1):37-47. doi:10.1177/0272989X12458159.Med Decis Making45. Müller-Engelmann M, Donner-Banzhoff N, Keller H, et al. When decisions should be shared: a study of social norms in medical decision making using a factorial survey approach. PubMed

46. 2007;101(4):205-211.Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich46. Mccaffery KJ, Shepherd HL, Trevena L, et al. Shared decision-making in Australia. PubMed

47. 2014;20(2):311-318. doi:10.1007/s12028-013-9922-2.Neurocrit Care

47. Rubin MA. The Collaborative Autonomy Model of Medical Decision-Making. 48. 2013;70(1 Suppl):141S-158S. doi:10.1177/1077558712461952.Med Care Res Rev PubMed

48. McCullough LB. The professional medical ethics model of decision making under conditions of clinical uncertainty. PubMed

49. 2009;87(2):368–390.Milbank Q49. Satterfield JM, Spring B, Brownson RC, et al. Toward a Transdisciplinary Model of Evidence-Based Practice. PubMed

50. 2015;25(3):276-282. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2015.02.002.Womens Health Issues50. Moore JE, Titler MG, Kane Low L, Dalton VK, Sampselle CM. Transforming Patient-Centered Care: Development of the Evidence Informed Decision Making through Engagement Model. PubMed

51. 1997;44(5):681-692.Soc Sci Med51. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). PubMed

52. 2010;80(2):164-172. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.015.Patient Educ Couns52. Stacey D, Légaré F, Pouliot S, Kryworuchko J, Dunn S. Shared decision making models to inform an interprofessional perspective on decision making: a theory analysis. PubMed

53. 2013;70(1 Suppl):94S-112S. doi:10.1177/1077558712459216.Med Care Res Rev53. Epstein RM, Gramling RE. What is shared in shared decision making? Complex decisions when the evidence is unclear. PubMed

54. 2010;304(8):903-904. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1208.JAMA54. Kon AA. The shared decision-making continuum. PubMed

55. 2008;30(3):429-444. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01064.x.Sociol Health Illn55. Rapley T. Distributed decision making: the anatomy of decisions-in-action. PubMed

56. 1997;12(6):339-345.J Gen Intern Med56. Braddock CH 3rd, Fihn SD, Levinson W, Jonsen AR, Pearlman RA. How doctors and patients discuss routine clinical decisions. Informed decision making in the outpatient setting. PubMed

57. 1999;282(24):2313-2320.JAMA57. Braddock CH 3rd, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. PubMed

58. 2009;69(12):1805-1812. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.056.Soc Sci Med58. Smith SK, Dixon A, Trevena L, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ. Exploring patient involvement in healthcare decision making across different education and functional health literacy groups.

2006;9(4):321-332. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00404.x.Health Expect. PubMed

59. Towle A, Godolphin W, Grams G, Lamarre A. Putting informed and shared decision making into practice. PubMed

60. 2011;17(4):554-564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01515.x.J Eval Clin Pract60. Légaré F, Stacey D, Gagnon S, et al. Validating a conceptual model for an interprofessional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study. PubMed

1. Hoffmann TC, Montori VM, Del Mar C. The connection between evidence-based medicine and shared decision making. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1295-1296. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10186. PubMed

2. Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JC. Shared decision making: Concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(10):1172-1179. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022. PubMed

3. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361-1367. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. PubMed

4. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(5):651-661. PubMed

5. Ofstad EH, Frich JC, Schei E, Frankel RM, Gulbrandsen P. What is a medical decision? A units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(7):915-921. doi:10.1164/rccm.201008-1214OC. PubMed

22. Müller-Engelmann M, Keller H, Donner-Banzhoff N, Krones T. Shared decision making in medicine: The influence of situational treatment factors. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(2):240-246. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.028. PubMed

23. Whitney SN. A New Model of Medical Decisions: Exploring the Limits of Shared Decision Making. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):275-280. doi:10.1177/0272989X03256006. PubMed

24. Légaré F, Bekker H, Desroches S, et al. How can continuing professional development better promote shared decision-making? Perspectives from an international collaboration. Implement Sci. 2011;6:68. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-68. PubMed

25. Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301-312. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. PubMed

26. Moumjid N, Gafni A, Brémond A, Carrère MO. Shared decision making in the medical taxonomy based on physician statements in hospital encounters: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010098. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010098. PubMed

6. Fowler FJ, Levin CA, Sepucha KR. Informing and involving patients to improve the quality of medical decisions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):699-706. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0003. PubMed

7. Weiner SJ, Kelly B, Ashley N, et al. Content coding for contextualization of care: evaluating physician performance at patient-centered decision making. Med Decis Making. 2014;34(1):97-106. doi:10.1177/0272989X13493146. PubMed

8. Weiner SJ, Schwartz A, Sharma G, et al. Patient-centered decision making and health care outcomes: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):573-579. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00001. PubMed

9. Matthias MS, Salyers MP, Frankel RM. Re-thinking shared decision-making: context matters. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(2):176-179. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.01.006 PubMed

10. Clayman ML, Bylund CL, Chewning B, Makoul G. The Impact of Patient Participation in Health Decisions Within Medical Encounters: A Systematic Review. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(4):427-452. doi:10.1177/0272989X15613530. PubMed

11. Shay LA, Lafata JE. Understanding patient perceptions of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):295-301. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.017. PubMed

12. Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9-18. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004. PubMed