User login

Patients Concerned about Hospitalist Service Handovers

Background: Service handovers contribute to discontinuity of care in hospitalized patients. Research on hospitalist service handovers is limited, and no previous study has examined the service handover from the patient’s perspective.

Study design: Interview-based, qualitative analysis.

Setting: Urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: Researchers interviewed 40 hospitalized patients using a semi-structured nine-question interview regarding their attending hospitalist service change. The constant comparative method was used to identify recurrent themes in patient responses. The research team identified six themes representative of patient concerns during service change: physician-patient communication, transparency in communication, hospitalist-specialist communication, new opportunities due to transition, bedside manner, and indifference toward the transition.

Authors used the six themes to develop a model for the ideal service handover, utilizing open lines of communication, facilitated by multiple modalities and disciplines, and recognizing the patient’s role as the primary stakeholder in the transition of care.

Bottom line: Incorporating patients’ perspective presents an opportunity to improve communication and efficiency during hospitalist service transitions.

Citation: Wray CM, Farnan JM, Arora VM, Meltzer DO. A qualitative analysis of patients’ experience with hospitalist service handovers [published online ahead of print May 11, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2608.

Background: Service handovers contribute to discontinuity of care in hospitalized patients. Research on hospitalist service handovers is limited, and no previous study has examined the service handover from the patient’s perspective.

Study design: Interview-based, qualitative analysis.

Setting: Urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: Researchers interviewed 40 hospitalized patients using a semi-structured nine-question interview regarding their attending hospitalist service change. The constant comparative method was used to identify recurrent themes in patient responses. The research team identified six themes representative of patient concerns during service change: physician-patient communication, transparency in communication, hospitalist-specialist communication, new opportunities due to transition, bedside manner, and indifference toward the transition.

Authors used the six themes to develop a model for the ideal service handover, utilizing open lines of communication, facilitated by multiple modalities and disciplines, and recognizing the patient’s role as the primary stakeholder in the transition of care.

Bottom line: Incorporating patients’ perspective presents an opportunity to improve communication and efficiency during hospitalist service transitions.

Citation: Wray CM, Farnan JM, Arora VM, Meltzer DO. A qualitative analysis of patients’ experience with hospitalist service handovers [published online ahead of print May 11, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2608.

Background: Service handovers contribute to discontinuity of care in hospitalized patients. Research on hospitalist service handovers is limited, and no previous study has examined the service handover from the patient’s perspective.

Study design: Interview-based, qualitative analysis.

Setting: Urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: Researchers interviewed 40 hospitalized patients using a semi-structured nine-question interview regarding their attending hospitalist service change. The constant comparative method was used to identify recurrent themes in patient responses. The research team identified six themes representative of patient concerns during service change: physician-patient communication, transparency in communication, hospitalist-specialist communication, new opportunities due to transition, bedside manner, and indifference toward the transition.

Authors used the six themes to develop a model for the ideal service handover, utilizing open lines of communication, facilitated by multiple modalities and disciplines, and recognizing the patient’s role as the primary stakeholder in the transition of care.

Bottom line: Incorporating patients’ perspective presents an opportunity to improve communication and efficiency during hospitalist service transitions.

Citation: Wray CM, Farnan JM, Arora VM, Meltzer DO. A qualitative analysis of patients’ experience with hospitalist service handovers [published online ahead of print May 11, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2608.

Warfarin Reduces Risk of Ischemic Stroke in High-Risk Patients

Background: For patients with atrial fibrillation and history of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), the risk of further ICH and the benefit of antithrombotic agents for stroke risk reduction remain unclear.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan.

Synopsis: Using the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan, researchers identified 307,640 patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score >/= 2. Of this group, 12,917 patients with a history of ICH were identified and separated into three groups: no treatment, antiplatelet treatment, or warfarin. Among the no treatment group, the rate of ICH and ischemic cerebrovascular accident were 4.2 and 5.8 per 100 person-years, respectively. Among patients on antiplatelet therapy, the rates were 5.3% and 5.2%, respectively. Among patients on warfarin, the number needed to treat (NNT) for preventing one ischemic stroke was lower than the number needed to harm (NNH) for producing one ICH among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score >/= 6. In patients with lower CHA2DS2-VASc scores, the NNT was higher than NNH.

Bottom line: Treatment with warfarin may benefit patients with atrial fibrillation and prior ICH with CHA2DS2-VASc scores >/= 6, but risk likely outweighs benefit in patients with lower scores.

Citation: Chao TF, Liu CJ, Liao JN, et al. Use of oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation who have a history of intracranial hemorrhage. Circulation. 2016;133(16):1540-1547.

Background: For patients with atrial fibrillation and history of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), the risk of further ICH and the benefit of antithrombotic agents for stroke risk reduction remain unclear.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan.

Synopsis: Using the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan, researchers identified 307,640 patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score >/= 2. Of this group, 12,917 patients with a history of ICH were identified and separated into three groups: no treatment, antiplatelet treatment, or warfarin. Among the no treatment group, the rate of ICH and ischemic cerebrovascular accident were 4.2 and 5.8 per 100 person-years, respectively. Among patients on antiplatelet therapy, the rates were 5.3% and 5.2%, respectively. Among patients on warfarin, the number needed to treat (NNT) for preventing one ischemic stroke was lower than the number needed to harm (NNH) for producing one ICH among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score >/= 6. In patients with lower CHA2DS2-VASc scores, the NNT was higher than NNH.

Bottom line: Treatment with warfarin may benefit patients with atrial fibrillation and prior ICH with CHA2DS2-VASc scores >/= 6, but risk likely outweighs benefit in patients with lower scores.

Citation: Chao TF, Liu CJ, Liao JN, et al. Use of oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation who have a history of intracranial hemorrhage. Circulation. 2016;133(16):1540-1547.

Background: For patients with atrial fibrillation and history of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), the risk of further ICH and the benefit of antithrombotic agents for stroke risk reduction remain unclear.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan.

Synopsis: Using the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan, researchers identified 307,640 patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score >/= 2. Of this group, 12,917 patients with a history of ICH were identified and separated into three groups: no treatment, antiplatelet treatment, or warfarin. Among the no treatment group, the rate of ICH and ischemic cerebrovascular accident were 4.2 and 5.8 per 100 person-years, respectively. Among patients on antiplatelet therapy, the rates were 5.3% and 5.2%, respectively. Among patients on warfarin, the number needed to treat (NNT) for preventing one ischemic stroke was lower than the number needed to harm (NNH) for producing one ICH among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score >/= 6. In patients with lower CHA2DS2-VASc scores, the NNT was higher than NNH.

Bottom line: Treatment with warfarin may benefit patients with atrial fibrillation and prior ICH with CHA2DS2-VASc scores >/= 6, but risk likely outweighs benefit in patients with lower scores.

Citation: Chao TF, Liu CJ, Liao JN, et al. Use of oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation who have a history of intracranial hemorrhage. Circulation. 2016;133(16):1540-1547.

Hospital Mobility Program Maintains Older Patients’ Mobility after Discharge

Background: Older hospitalized patients experience decreased mobility while in the hospital and suffer from impaired function and mobility after they are discharged. The efficacy and safety of inpatient mobility programs are unknown.

Study design: Randomized, single-blinded controlled trial.

Setting: Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Alabama.

Synopsis: The study included 100 patients age 65 years and older admitted to general medical wards. Researchers excluded cognitively impaired patients and patients with limited life expectancy. Intervention patients received a standardized hospital mobility protocol, with up to twice daily 15- to 20-minute visits by research personnel. Visits sought to progressively increase mobility from assisted sitting to ambulation. Physical activity was coupled with a behavioral intervention focused on goal setting and mobility barrier resolution. The comparison group received usual care. Outcomes included changes in activities of daily living (ADLs) and community mobility one month after hospital discharge.

One month after hospitalization, there were no differences in ADLs between intervention and control patients. Patients in the mobility protocol arm, however, maintained their prehospital community mobility, whereas usual-care patients had a statistically significant decrease in mobility as measured by the Life-Space Assessment. There was no difference in falls between groups.

Bottom line: A hospital mobility intervention was a safe and effective means of preserving community mobility. Future effectiveness studies are needed to demonstrate feasibility and outcomes in real-world settings.

Citation: Brown CJ, Foley KT, Lowman JD Jr, et al. Comparison of posthospitalization function and community mobility in hospital mobility program and usual care patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):921-927.

Short Take

Topical NSAIDs Effective for Back Pain

Using ketoprofen gel in addition to intravenous dexketoprofen improves pain relief in patients presenting to the emergency department with low back pain.

Citation: Serinken M, Eken C, Tunay K, Golcuk Y. Ketoprofen gel improves low back pain in addition to IV dexkeoprofen: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1458-1461.

Background: Older hospitalized patients experience decreased mobility while in the hospital and suffer from impaired function and mobility after they are discharged. The efficacy and safety of inpatient mobility programs are unknown.

Study design: Randomized, single-blinded controlled trial.

Setting: Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Alabama.

Synopsis: The study included 100 patients age 65 years and older admitted to general medical wards. Researchers excluded cognitively impaired patients and patients with limited life expectancy. Intervention patients received a standardized hospital mobility protocol, with up to twice daily 15- to 20-minute visits by research personnel. Visits sought to progressively increase mobility from assisted sitting to ambulation. Physical activity was coupled with a behavioral intervention focused on goal setting and mobility barrier resolution. The comparison group received usual care. Outcomes included changes in activities of daily living (ADLs) and community mobility one month after hospital discharge.

One month after hospitalization, there were no differences in ADLs between intervention and control patients. Patients in the mobility protocol arm, however, maintained their prehospital community mobility, whereas usual-care patients had a statistically significant decrease in mobility as measured by the Life-Space Assessment. There was no difference in falls between groups.

Bottom line: A hospital mobility intervention was a safe and effective means of preserving community mobility. Future effectiveness studies are needed to demonstrate feasibility and outcomes in real-world settings.

Citation: Brown CJ, Foley KT, Lowman JD Jr, et al. Comparison of posthospitalization function and community mobility in hospital mobility program and usual care patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):921-927.

Short Take

Topical NSAIDs Effective for Back Pain

Using ketoprofen gel in addition to intravenous dexketoprofen improves pain relief in patients presenting to the emergency department with low back pain.

Citation: Serinken M, Eken C, Tunay K, Golcuk Y. Ketoprofen gel improves low back pain in addition to IV dexkeoprofen: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1458-1461.

Background: Older hospitalized patients experience decreased mobility while in the hospital and suffer from impaired function and mobility after they are discharged. The efficacy and safety of inpatient mobility programs are unknown.

Study design: Randomized, single-blinded controlled trial.

Setting: Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Alabama.

Synopsis: The study included 100 patients age 65 years and older admitted to general medical wards. Researchers excluded cognitively impaired patients and patients with limited life expectancy. Intervention patients received a standardized hospital mobility protocol, with up to twice daily 15- to 20-minute visits by research personnel. Visits sought to progressively increase mobility from assisted sitting to ambulation. Physical activity was coupled with a behavioral intervention focused on goal setting and mobility barrier resolution. The comparison group received usual care. Outcomes included changes in activities of daily living (ADLs) and community mobility one month after hospital discharge.

One month after hospitalization, there were no differences in ADLs between intervention and control patients. Patients in the mobility protocol arm, however, maintained their prehospital community mobility, whereas usual-care patients had a statistically significant decrease in mobility as measured by the Life-Space Assessment. There was no difference in falls between groups.

Bottom line: A hospital mobility intervention was a safe and effective means of preserving community mobility. Future effectiveness studies are needed to demonstrate feasibility and outcomes in real-world settings.

Citation: Brown CJ, Foley KT, Lowman JD Jr, et al. Comparison of posthospitalization function and community mobility in hospital mobility program and usual care patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):921-927.

Short Take

Topical NSAIDs Effective for Back Pain

Using ketoprofen gel in addition to intravenous dexketoprofen improves pain relief in patients presenting to the emergency department with low back pain.

Citation: Serinken M, Eken C, Tunay K, Golcuk Y. Ketoprofen gel improves low back pain in addition to IV dexkeoprofen: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1458-1461.

Daily Round Checklists in ICU Setting Don’t Reduce Mortality

Background: Checklists, goal assessment, and clinician prompting have shown promise in improving communication, care-process adherence, and clinical outcomes in ICUs and acute-care settings, but existing studies are limited by nonrandomized design and high-income settings.

Study design: Cluster randomized trial.

Setting: 118 academic and nonacademic ICUs in Brazil.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 6,761 patients to a quality improvement (QI) intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting. Analyses were adjusted for patient’s severity of illness and the ICU’s adjusted mortality ratio. There was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82–1.26). The QI intervention had no effect on 10 secondary clinical outcomes (e.g., ventilator-associated pneumonia). The intervention improved adherence with four of seven care processes (e.g., use of low tidal volumes) and two of six factors of the safety climate. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, only urinary catheter use remained statistically significant.

Strengths of this study are the large number of ICUs involved and a high rate of QI adherence. Limitations include the setting in a resource-constrained nation, limited success with adopting changes in care processes, and relatively short intervention period of six months.

Bottom line: In a large Brazilian randomized control trial, implementation of daily round checklists, along with goal setting and clinician prompting, did not change in-hospital mortality. It is possible that a longer intervention period would have found improved outcomes.

Citation: Writing Group for the CHECKLIST-ICU Investigators and the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network (BRICNet), Cavalcanti AB, Bozza FA, et al. Effect of a quality improvement intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting on mortality of critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(14):1480-1490.

Short Take

More Restrictions on Fluoroquinolones

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recommended avoidance of fluoroquinolone drugs, which are often used for patients with acute bronchitis, acute sinusitis, and uncomplicated UTI, due to the potential of serious side effects. Exceptions should be made for cases with no other treatment options.

Citation: Fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs: drug safety communication - FDA advises restricting use for certain uncomplicated infections. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website.

Background: Checklists, goal assessment, and clinician prompting have shown promise in improving communication, care-process adherence, and clinical outcomes in ICUs and acute-care settings, but existing studies are limited by nonrandomized design and high-income settings.

Study design: Cluster randomized trial.

Setting: 118 academic and nonacademic ICUs in Brazil.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 6,761 patients to a quality improvement (QI) intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting. Analyses were adjusted for patient’s severity of illness and the ICU’s adjusted mortality ratio. There was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82–1.26). The QI intervention had no effect on 10 secondary clinical outcomes (e.g., ventilator-associated pneumonia). The intervention improved adherence with four of seven care processes (e.g., use of low tidal volumes) and two of six factors of the safety climate. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, only urinary catheter use remained statistically significant.

Strengths of this study are the large number of ICUs involved and a high rate of QI adherence. Limitations include the setting in a resource-constrained nation, limited success with adopting changes in care processes, and relatively short intervention period of six months.

Bottom line: In a large Brazilian randomized control trial, implementation of daily round checklists, along with goal setting and clinician prompting, did not change in-hospital mortality. It is possible that a longer intervention period would have found improved outcomes.

Citation: Writing Group for the CHECKLIST-ICU Investigators and the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network (BRICNet), Cavalcanti AB, Bozza FA, et al. Effect of a quality improvement intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting on mortality of critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(14):1480-1490.

Short Take

More Restrictions on Fluoroquinolones

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recommended avoidance of fluoroquinolone drugs, which are often used for patients with acute bronchitis, acute sinusitis, and uncomplicated UTI, due to the potential of serious side effects. Exceptions should be made for cases with no other treatment options.

Citation: Fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs: drug safety communication - FDA advises restricting use for certain uncomplicated infections. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website.

Background: Checklists, goal assessment, and clinician prompting have shown promise in improving communication, care-process adherence, and clinical outcomes in ICUs and acute-care settings, but existing studies are limited by nonrandomized design and high-income settings.

Study design: Cluster randomized trial.

Setting: 118 academic and nonacademic ICUs in Brazil.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 6,761 patients to a quality improvement (QI) intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting. Analyses were adjusted for patient’s severity of illness and the ICU’s adjusted mortality ratio. There was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82–1.26). The QI intervention had no effect on 10 secondary clinical outcomes (e.g., ventilator-associated pneumonia). The intervention improved adherence with four of seven care processes (e.g., use of low tidal volumes) and two of six factors of the safety climate. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, only urinary catheter use remained statistically significant.

Strengths of this study are the large number of ICUs involved and a high rate of QI adherence. Limitations include the setting in a resource-constrained nation, limited success with adopting changes in care processes, and relatively short intervention period of six months.

Bottom line: In a large Brazilian randomized control trial, implementation of daily round checklists, along with goal setting and clinician prompting, did not change in-hospital mortality. It is possible that a longer intervention period would have found improved outcomes.

Citation: Writing Group for the CHECKLIST-ICU Investigators and the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network (BRICNet), Cavalcanti AB, Bozza FA, et al. Effect of a quality improvement intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting on mortality of critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(14):1480-1490.

Short Take

More Restrictions on Fluoroquinolones

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recommended avoidance of fluoroquinolone drugs, which are often used for patients with acute bronchitis, acute sinusitis, and uncomplicated UTI, due to the potential of serious side effects. Exceptions should be made for cases with no other treatment options.

Citation: Fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs: drug safety communication - FDA advises restricting use for certain uncomplicated infections. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website.

Nonemergency Use of Antipsychotics in Patients with Dementia

Background: Patients with dementia often exhibit behavioral problems, such as agitation and psychosis. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) produced a consensus report on the use of antipsychotics in patients with dementia who also exhibit agitation/psychosis.

Study design: Expert panel review of multiple studies and consensus opinions of experienced clinicians.

Synopsis: While the use of antipsychotics to treat behavioral symptoms in patients with dementia is common, it is important to use these medications judiciously, especially in nonemergency cases. The APA recommends antipsychotics for treatment of agitation in these patients only when symptoms are severe or dangerous or cause significant distress to the patient.

When providers determine that benefits exceed risks, antipsychotic treatment should be initiated at a low dose and carefully titrated up to the minimum effective dose. If there is no significant response after a four-week trial of an adequate dose, tapering and withdrawing antipsychotic medication is recommended. Haloperidol should not be used as a first-line agent. The APA guidelines are not intended to apply to treatment in an urgent context, such as acute delirium.

Bottom line: The APA has provided practical guidelines to direct care of dementia patients. These guidelines are not intended to apply to individuals who are receiving antipsychotics in an urgent context or who receive antipsychotics for other disorders (e.g., chronic psychotic illness).

Citation: Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Eyler AE, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(5):543-546.

Short Take

Colistin-Resistant E. coli in the U.S.

The presence of mcr-1, a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene indicating the presence of a truly pan-drug-resistant bacteria, has been identified for the first time in the United States.

Citation: McGann P, Snesrud E, Maybank R, et al. Escherichia coli harboring mcr-1 and blaCTX-M on a novel IncF plasmid: first report of mcr-1 in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4420-4421.

Background: Patients with dementia often exhibit behavioral problems, such as agitation and psychosis. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) produced a consensus report on the use of antipsychotics in patients with dementia who also exhibit agitation/psychosis.

Study design: Expert panel review of multiple studies and consensus opinions of experienced clinicians.

Synopsis: While the use of antipsychotics to treat behavioral symptoms in patients with dementia is common, it is important to use these medications judiciously, especially in nonemergency cases. The APA recommends antipsychotics for treatment of agitation in these patients only when symptoms are severe or dangerous or cause significant distress to the patient.

When providers determine that benefits exceed risks, antipsychotic treatment should be initiated at a low dose and carefully titrated up to the minimum effective dose. If there is no significant response after a four-week trial of an adequate dose, tapering and withdrawing antipsychotic medication is recommended. Haloperidol should not be used as a first-line agent. The APA guidelines are not intended to apply to treatment in an urgent context, such as acute delirium.

Bottom line: The APA has provided practical guidelines to direct care of dementia patients. These guidelines are not intended to apply to individuals who are receiving antipsychotics in an urgent context or who receive antipsychotics for other disorders (e.g., chronic psychotic illness).

Citation: Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Eyler AE, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(5):543-546.

Short Take

Colistin-Resistant E. coli in the U.S.

The presence of mcr-1, a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene indicating the presence of a truly pan-drug-resistant bacteria, has been identified for the first time in the United States.

Citation: McGann P, Snesrud E, Maybank R, et al. Escherichia coli harboring mcr-1 and blaCTX-M on a novel IncF plasmid: first report of mcr-1 in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4420-4421.

Background: Patients with dementia often exhibit behavioral problems, such as agitation and psychosis. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) produced a consensus report on the use of antipsychotics in patients with dementia who also exhibit agitation/psychosis.

Study design: Expert panel review of multiple studies and consensus opinions of experienced clinicians.

Synopsis: While the use of antipsychotics to treat behavioral symptoms in patients with dementia is common, it is important to use these medications judiciously, especially in nonemergency cases. The APA recommends antipsychotics for treatment of agitation in these patients only when symptoms are severe or dangerous or cause significant distress to the patient.

When providers determine that benefits exceed risks, antipsychotic treatment should be initiated at a low dose and carefully titrated up to the minimum effective dose. If there is no significant response after a four-week trial of an adequate dose, tapering and withdrawing antipsychotic medication is recommended. Haloperidol should not be used as a first-line agent. The APA guidelines are not intended to apply to treatment in an urgent context, such as acute delirium.

Bottom line: The APA has provided practical guidelines to direct care of dementia patients. These guidelines are not intended to apply to individuals who are receiving antipsychotics in an urgent context or who receive antipsychotics for other disorders (e.g., chronic psychotic illness).

Citation: Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Eyler AE, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(5):543-546.

Short Take

Colistin-Resistant E. coli in the U.S.

The presence of mcr-1, a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene indicating the presence of a truly pan-drug-resistant bacteria, has been identified for the first time in the United States.

Citation: McGann P, Snesrud E, Maybank R, et al. Escherichia coli harboring mcr-1 and blaCTX-M on a novel IncF plasmid: first report of mcr-1 in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4420-4421.

Frailty Scores Predict Post-Discharge Outcomes

Background: Research has shown that frail hospital patients are at increased risk of readmission and death. Although several frailty assessment tools have been developed, few studies have examined the application of such tools to predict post-discharge outcomes of hospitalized patients.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: General medical wards in Edmonton, Canada.

Synopsis: Researchers enrolled 495 adult patients from general medicine wards in two teaching hospitals. Long-term care residents and patients with limited life expectancy were excluded. Each patient was assessed using three different frailty assessment tools: the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), the Fried score, and the Timed Up and Go Test (TUGT). The primary outcomes were 30-day readmission and all-cause mortality. Outcomes were assessed by research personnel blinded to frailty status.

Overall, 211 (43%) patients were classified as frail by at least one tool. In general, frail patients were older, had more comorbidities, and had more frequent hospitalizations than non-frail patients. Agreement among the tools was poor, and only 49 patients met frailty criteria by all three definitions. The CFS was the only tool found to be an independent predictor of adverse 30-day outcomes (23% versus 14% for not frail, P=0.005; adjusted odds ratio, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.19–3.41).

Bottom line: As an independent predictor of adverse post-discharge outcomes, the CFS is a useful tool in both research and clinical settings. The CFS requires little time and no special equipment to administer.

Citation: Belga S, Majumdar SR, Kahlon S, et al. Comparing three different measures of frailty in medical inpatients: multicenter prospective cohort study examining 30-day risk of readmission or death. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):556-562.

Short Take

National Program Reduces CAUTI

A national prevention program aimed at reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) has been shown to reduce both catheter use and rates of CAUTI in non-ICU patients.

Citation: Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2111-2119.

Background: Research has shown that frail hospital patients are at increased risk of readmission and death. Although several frailty assessment tools have been developed, few studies have examined the application of such tools to predict post-discharge outcomes of hospitalized patients.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: General medical wards in Edmonton, Canada.

Synopsis: Researchers enrolled 495 adult patients from general medicine wards in two teaching hospitals. Long-term care residents and patients with limited life expectancy were excluded. Each patient was assessed using three different frailty assessment tools: the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), the Fried score, and the Timed Up and Go Test (TUGT). The primary outcomes were 30-day readmission and all-cause mortality. Outcomes were assessed by research personnel blinded to frailty status.

Overall, 211 (43%) patients were classified as frail by at least one tool. In general, frail patients were older, had more comorbidities, and had more frequent hospitalizations than non-frail patients. Agreement among the tools was poor, and only 49 patients met frailty criteria by all three definitions. The CFS was the only tool found to be an independent predictor of adverse 30-day outcomes (23% versus 14% for not frail, P=0.005; adjusted odds ratio, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.19–3.41).

Bottom line: As an independent predictor of adverse post-discharge outcomes, the CFS is a useful tool in both research and clinical settings. The CFS requires little time and no special equipment to administer.

Citation: Belga S, Majumdar SR, Kahlon S, et al. Comparing three different measures of frailty in medical inpatients: multicenter prospective cohort study examining 30-day risk of readmission or death. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):556-562.

Short Take

National Program Reduces CAUTI

A national prevention program aimed at reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) has been shown to reduce both catheter use and rates of CAUTI in non-ICU patients.

Citation: Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2111-2119.

Background: Research has shown that frail hospital patients are at increased risk of readmission and death. Although several frailty assessment tools have been developed, few studies have examined the application of such tools to predict post-discharge outcomes of hospitalized patients.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: General medical wards in Edmonton, Canada.

Synopsis: Researchers enrolled 495 adult patients from general medicine wards in two teaching hospitals. Long-term care residents and patients with limited life expectancy were excluded. Each patient was assessed using three different frailty assessment tools: the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), the Fried score, and the Timed Up and Go Test (TUGT). The primary outcomes were 30-day readmission and all-cause mortality. Outcomes were assessed by research personnel blinded to frailty status.

Overall, 211 (43%) patients were classified as frail by at least one tool. In general, frail patients were older, had more comorbidities, and had more frequent hospitalizations than non-frail patients. Agreement among the tools was poor, and only 49 patients met frailty criteria by all three definitions. The CFS was the only tool found to be an independent predictor of adverse 30-day outcomes (23% versus 14% for not frail, P=0.005; adjusted odds ratio, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.19–3.41).

Bottom line: As an independent predictor of adverse post-discharge outcomes, the CFS is a useful tool in both research and clinical settings. The CFS requires little time and no special equipment to administer.

Citation: Belga S, Majumdar SR, Kahlon S, et al. Comparing three different measures of frailty in medical inpatients: multicenter prospective cohort study examining 30-day risk of readmission or death. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):556-562.

Short Take

National Program Reduces CAUTI

A national prevention program aimed at reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) has been shown to reduce both catheter use and rates of CAUTI in non-ICU patients.

Citation: Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2111-2119.

Hospitalist Staffing Affects 30-Day All-Cause Readmission Rates

Background: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) tracks 30-day all-cause readmission rates as a quality measure. Prior studies have looked at various hospital factors associated with lower readmission rates but have not looked at hospitalist staffing levels, level of physician integration with the hospital, and the adoption of a medical home model.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Private hospitals.

Synopsis: Using the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals, CMS Hospital Compare, and Area Health Resources File of private hospitals with no missing data, the study reviewed data from 1,756 hospitals and found the median 30-day all-cause readmission rate to be 16%, with the middle 50% of hospitals’ readmission rate between 15.2% and 16.5%. All hospitals used hospitalists to provide care. Fifty-one percent of hospitals reported fully integrated, or employed, physicians. Twenty-nine percent reported establishment of a medical home.

The study found that higher hospitalist staffing levels were associated with significantly lower readmission rates. Fully integrated hospitals had a lower readmission rate than not fully integrated (15.86% versus 15.93%). Also, physician-owned hospitals had a lower readmission rate than non-physician-owned hospitals, and hospitals that had adopted a medical home model had significantly lower readmission rates. Readmission rates were significantly higher for major teaching hospitals (16.9% versus 15.76% minor teaching versus 15.83% nonteaching).

Bottom line: High hospitalist staffing levels, full integration of the hospitalists, and physician-owned hospitals were associated with lower 30-day all-cause readmission rates for private hospitals.

Citation: Al-Amin M. Hospital characteristics and 30-day all-cause readmission rates [published online ahead of print May 17, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2606

Background: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) tracks 30-day all-cause readmission rates as a quality measure. Prior studies have looked at various hospital factors associated with lower readmission rates but have not looked at hospitalist staffing levels, level of physician integration with the hospital, and the adoption of a medical home model.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Private hospitals.

Synopsis: Using the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals, CMS Hospital Compare, and Area Health Resources File of private hospitals with no missing data, the study reviewed data from 1,756 hospitals and found the median 30-day all-cause readmission rate to be 16%, with the middle 50% of hospitals’ readmission rate between 15.2% and 16.5%. All hospitals used hospitalists to provide care. Fifty-one percent of hospitals reported fully integrated, or employed, physicians. Twenty-nine percent reported establishment of a medical home.

The study found that higher hospitalist staffing levels were associated with significantly lower readmission rates. Fully integrated hospitals had a lower readmission rate than not fully integrated (15.86% versus 15.93%). Also, physician-owned hospitals had a lower readmission rate than non-physician-owned hospitals, and hospitals that had adopted a medical home model had significantly lower readmission rates. Readmission rates were significantly higher for major teaching hospitals (16.9% versus 15.76% minor teaching versus 15.83% nonteaching).

Bottom line: High hospitalist staffing levels, full integration of the hospitalists, and physician-owned hospitals were associated with lower 30-day all-cause readmission rates for private hospitals.

Citation: Al-Amin M. Hospital characteristics and 30-day all-cause readmission rates [published online ahead of print May 17, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2606

Background: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) tracks 30-day all-cause readmission rates as a quality measure. Prior studies have looked at various hospital factors associated with lower readmission rates but have not looked at hospitalist staffing levels, level of physician integration with the hospital, and the adoption of a medical home model.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Private hospitals.

Synopsis: Using the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals, CMS Hospital Compare, and Area Health Resources File of private hospitals with no missing data, the study reviewed data from 1,756 hospitals and found the median 30-day all-cause readmission rate to be 16%, with the middle 50% of hospitals’ readmission rate between 15.2% and 16.5%. All hospitals used hospitalists to provide care. Fifty-one percent of hospitals reported fully integrated, or employed, physicians. Twenty-nine percent reported establishment of a medical home.

The study found that higher hospitalist staffing levels were associated with significantly lower readmission rates. Fully integrated hospitals had a lower readmission rate than not fully integrated (15.86% versus 15.93%). Also, physician-owned hospitals had a lower readmission rate than non-physician-owned hospitals, and hospitals that had adopted a medical home model had significantly lower readmission rates. Readmission rates were significantly higher for major teaching hospitals (16.9% versus 15.76% minor teaching versus 15.83% nonteaching).

Bottom line: High hospitalist staffing levels, full integration of the hospitalists, and physician-owned hospitals were associated with lower 30-day all-cause readmission rates for private hospitals.

Citation: Al-Amin M. Hospital characteristics and 30-day all-cause readmission rates [published online ahead of print May 17, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2606

Oral Antibiotics for Infective Endocarditis May Be Safe in Low-Risk Patients

Background: Treating infective endocarditis with four to six weeks of intravenous antibiotics carries a high cost. There are data to support oral antibiotics for right-sided endocarditis due to methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (with ciprofloxacin and rifampicin), but experience in using oral antibiotics for infective endocarditis is limited.

Study design: Cohort study.

Setting: Large academic hospital in France.

Synopsis: The researchers included 426 patients with definitive or probable endocarditis by Duke criteria. After an initial period of treatment with intravenous (IV) antibiotics, 50% of the identified group was transitioned to oral antibiotics (amoxicillin alone in 50% and combinations of fluoroquinolones, rifampicin, amoxicillin, and clindamycin in the others).

The risk of death was not increased in the group treated with oral antibiotics when adjusted for the four biggest predictors of death (age >65, type 1 diabetes mellitus, disinsertion of prosthetic valve, and endocarditis due to S. aureus). Nine patients treated with IV antibiotics experienced relapsed endocarditis compared to two patients treated with oral antibiotics.

Patients selected for treatment with oral antibiotics were less likely to have severe disease, significant comorbidities, or infection with S. aureus. The length of treatment with IV antibiotics before switching to oral antibiotics varied widely.

Bottom line: It’s possible low-risk patients with infective endocarditis may be treated with oral antibiotics, but more data are needed.

Citation: Mzabi A, Kernéis S, Richaud C, Podglajen I, Fernandez-Gerlinger MP, Mainardi, JL. Switch to oral antibiotics in the treatment of infective endocarditis is not associated with increased risk of mortality in non-severely ill patients [published online ahead of print April 16, 2016]. Clin Microbiol Infect. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.003.

Background: Treating infective endocarditis with four to six weeks of intravenous antibiotics carries a high cost. There are data to support oral antibiotics for right-sided endocarditis due to methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (with ciprofloxacin and rifampicin), but experience in using oral antibiotics for infective endocarditis is limited.

Study design: Cohort study.

Setting: Large academic hospital in France.

Synopsis: The researchers included 426 patients with definitive or probable endocarditis by Duke criteria. After an initial period of treatment with intravenous (IV) antibiotics, 50% of the identified group was transitioned to oral antibiotics (amoxicillin alone in 50% and combinations of fluoroquinolones, rifampicin, amoxicillin, and clindamycin in the others).

The risk of death was not increased in the group treated with oral antibiotics when adjusted for the four biggest predictors of death (age >65, type 1 diabetes mellitus, disinsertion of prosthetic valve, and endocarditis due to S. aureus). Nine patients treated with IV antibiotics experienced relapsed endocarditis compared to two patients treated with oral antibiotics.

Patients selected for treatment with oral antibiotics were less likely to have severe disease, significant comorbidities, or infection with S. aureus. The length of treatment with IV antibiotics before switching to oral antibiotics varied widely.

Bottom line: It’s possible low-risk patients with infective endocarditis may be treated with oral antibiotics, but more data are needed.

Citation: Mzabi A, Kernéis S, Richaud C, Podglajen I, Fernandez-Gerlinger MP, Mainardi, JL. Switch to oral antibiotics in the treatment of infective endocarditis is not associated with increased risk of mortality in non-severely ill patients [published online ahead of print April 16, 2016]. Clin Microbiol Infect. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.003.

Background: Treating infective endocarditis with four to six weeks of intravenous antibiotics carries a high cost. There are data to support oral antibiotics for right-sided endocarditis due to methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (with ciprofloxacin and rifampicin), but experience in using oral antibiotics for infective endocarditis is limited.

Study design: Cohort study.

Setting: Large academic hospital in France.

Synopsis: The researchers included 426 patients with definitive or probable endocarditis by Duke criteria. After an initial period of treatment with intravenous (IV) antibiotics, 50% of the identified group was transitioned to oral antibiotics (amoxicillin alone in 50% and combinations of fluoroquinolones, rifampicin, amoxicillin, and clindamycin in the others).

The risk of death was not increased in the group treated with oral antibiotics when adjusted for the four biggest predictors of death (age >65, type 1 diabetes mellitus, disinsertion of prosthetic valve, and endocarditis due to S. aureus). Nine patients treated with IV antibiotics experienced relapsed endocarditis compared to two patients treated with oral antibiotics.

Patients selected for treatment with oral antibiotics were less likely to have severe disease, significant comorbidities, or infection with S. aureus. The length of treatment with IV antibiotics before switching to oral antibiotics varied widely.

Bottom line: It’s possible low-risk patients with infective endocarditis may be treated with oral antibiotics, but more data are needed.

Citation: Mzabi A, Kernéis S, Richaud C, Podglajen I, Fernandez-Gerlinger MP, Mainardi, JL. Switch to oral antibiotics in the treatment of infective endocarditis is not associated with increased risk of mortality in non-severely ill patients [published online ahead of print April 16, 2016]. Clin Microbiol Infect. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.003.

What Are the Strategies for Secondary Stroke Prevention after Transient Ischemic Attack?

Case

Mr. G is an 80-year-old man with a pacemaker, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation (AF) on warfarin, and tachy-brady syndrome. He presented after experiencing episodes in which he was unable to speak and had weakness on his right side. He had a normal neurological exam upon arrival to the ED, and his blood pressure was 160/80 mm Hg.

Overview

Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) are brief interruptions in brain perfusion that do not result in permanent neurologic damage. Up to half a million TIAs occur each year in the U.S., and they account for one third of acute cerebrovascular disease.1 While the term suggests that TIAs are benign, they are in fact an important warning sign of impending stroke and are essentially analogous to unstable angina. Some 10% of TIAs convert to full strokes within 90 days, but growing evidence suggests appropriate interventions can decrease this risk to 3%.2

Unfortunately, the symptoms of TIA have usually resolved by the time patients arrive at the hospital, which makes them challenging to diagnose. This article provides a summary of how to diagnose TIA accurately, using a focused history informed by cerebrovascular localization; how to triage, evaluate, and risk stratify patients; and how to implement preventative strategies.

Review of the Data

Classically, TIAs are defined as lasting less than 24 hours; however, 24 hours is an arbitrary number, and most TIAs last less than one hour.1 Furthermore, this definition has evolved with advances in neuroimaging that reveal that up to 50% of classically defined TIAs have evidence of infarct on MRI.1 There is no absolute temporal cut-off after which infarct is always seen on MRI, but longer duration of symptoms correlates with a higher likelihood of infarct. To reconcile these observations, a recently proposed definition stipulates that a true TIA lasts no more than one hour and does not show evidence of infarct on MRI.3

The causes of TIA are identical to those for ischemic stroke. Cerebral ischemia can result from an embolus, arterial thrombosis, or hypoperfusion due to arterial stenosis. Emboli can be cardiac, most commonly due to AF, or non-cardiac, stemming from a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque in the aortic arch, the carotid or vertebral artery, or an intracranial vessel. Atherosclerotic disease in the carotid arteries or intracranial vessels can also lead to thrombosis and occlusion or flow-related TIAs as a result of severe stenosis.

Risk factors for TIA mirror those for heart disease. Non-modifiable risk factors include older age, black race, male sex, and family history of stroke. Modifiable factors include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, tobacco smoking, diabetes, and AF.4

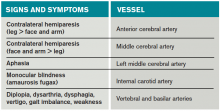

Most of the time, patients’ symptoms will have resolved by the time they are evaluated by a physician. Therefore, the diagnosis of TIA relies almost exclusively on the patient history. Eliciting a good history helps physicians determine whether the episode of transient neurologic dysfunction was caused by cerebral ischemia, as opposed to another mechanism, such as migraine or seizure. This calls for a basic understanding of cerebrovascular anatomy (see Table 1).

Types of Ischemia

Anterior cerebral artery ischemia causes contralateral leg weakness because it supplies the medial frontal and parietal lobes, where the legs in the sensorimotor homunculus are represented. Middle cerebral artery (MCA) ischemia causes contralateral face and arm weakness out of proportion to leg weakness. Ischemia in Broca’s area of the brain, which is supplied by the left MCA, may also cause expressive aphasia. Transient monocular blindness is a TIA of the retina due to atheroemboli originating from the internal carotid artery. Vertebrobasilar TIA is less common than anterior circulation TIA and manifests with brainstem symptoms that include diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, vertigo, gait imbalance, and weakness. In general, language and motor symptoms are more specific for cerebral ischemia and therefore more worrisome for TIA than sensory symptoms.5

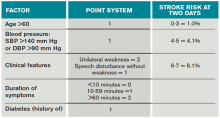

Once a clinical diagnosis of TIA is made, an ABCD2 score (age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of TIA, presence of diabetes) can be used to predict the short-term risk of subsequent stroke (see Table 2).6,7 A general rule of thumb is to admit patients who present within 72 hours of the event and have an ABCD2 score of three or higher for observation, work-up, and initiation of secondary prevention.1

Although only a small percentage of patients with TIA will have a stroke during the period of observation in the hospital, this approach may be cost effective based on the assumption that hospitalized patients are more likely to receive intravenous tissue plasminogen activator.8 The decision should also be guided by clinical judgment. It is reasonable to admit a patient whose diagnostic workup cannot be rapidly completed.1

The workup for TIA includes routine labs, EKG with cardiac monitoring, and brain imaging. Labs are useful to evaluate for other mimics of TIA such as hyponatremia and glucose abnormalities. In addition, risk factors such as hyperlipidemia and diabetes should be evaluated with fasting lipid panel and blood glucose. The purpose of EKG and telemetry is to identify MI and capture paroxysmal AF. The goal of imaging is to ascertain the presence of vascular disease and to exclude a non-ischemic etiology. While less likely to cause transient neurologic symptoms, a hemorrhagic event must be ruled out, as it would trigger a different management pathway.

Imaging for TIA

There are two primary modes of brain imaging: computed tomography (CT) and MRI. Most patients who are suspected to have had a TIA undergo CT scan, and an infarct is seen about 20% of the time.1 The presence of an infarct usually correlates with the duration of symptoms and has prognostic value. In one study, a new infarct was associated with four times higher risk of stroke in the subsequent 90 days.9 Diffusion-weighted imaging, an MR-based technique, is the preferred modality when it is available because of its higher sensitivity and specificity for identifying acute lesions.1 In an international and multicenter study, incorporating imaging data increased the discriminatory power of stroke prediction.10

Extracranial imaging is mandatory to rule out carotid stenosis as a potential etiology of TIA. The least invasive modality is ultrasound, which can detect carotid stenosis with a sensitivity and specificity approaching 80%.1 While both the intra- and extracranial vasculature can be concurrently assessed using MR- or CT-angiography (CTA), this is not usually necessary in the acute setting, because only detecting carotid stenosis will result in a management change.1

Carotid endarterectomy is standard for symptomatic patients with greater than 70% stenosis and is a consideration for symptomatic patients with greater than 50% stenosis if it is the most probable explanation for the ischemic event.11 Despite a comprehensive workup, about 50% of TIA cases remain cryptogenic.12 In some of these patients, AF can be detected using extended ambulatory cardiac monitoring.12

The goal of admitting high-risk patients is to expedite workup and initiate therapy. Two studies have shown that immediate initiation of preventative treatment significantly reduces the risk of stroke by as much as 80%.13,14 Unless there is a specific indication for anticoagulation, all TIA patients should be started on an antiplatelet agent such as aspirin or clopidogrel. A large randomized trial conducted in China and published in 2013 demonstrated that dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for 21 days, followed by clopidogrel monotherapy, reduced the risk of stroke compared to aspirin monotherapy. An international multicenter trial designed to test the efficacy of short-term dual antiplatelet therapy is ongoing, and if the benefit of this approach is confirmed, this will likely become the standard of care. Evidence-based indications for anticoagulation after TIA are restricted to AF and mural thrombus in the setting of recent MI. Patients with implanted mechanical devices, including left ventricular assist devices and metal heart valves, should also receive anticoagulation.15

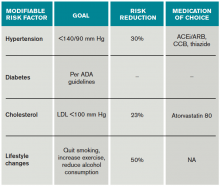

Risk factors should also be targeted in every case. Hypertension should be treated with a goal of lower than 140/90 mm Hg (or 130/80 mm Hg in diabetics and those with renal disease). Studies have shown that patients who are discharged with a blood pressure lower than 140/90 mm Hg are more likely to maintain this blood pressure at one-year follow-up.16 The choice of medication is less well studied, but drugs that act on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and thiazides are generally preferred.15 Treatment with a statin is recommended after cerebrovascular ischemic events, with a goal LDL under 100. This reduces risk of secondary stroke by about 20%.17

At discharge, it is also important to counsel patients on their role in preventing strokes. As with many diseases, making lifestyle changes is key to stroke prevention. Encourage smoking cessation and an increase in physical activity, and discourage heavy alcohol use. The association between smoking and the risk for first stroke is well established. Moderate to high-intensity exercise can reduce secondary stroke risk by as much as 50%18 (see Table 3). While light alcohol consumption can be protective against strokes, heavy use is strongly discouraged. Emerging data suggest obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may be another modifiable risk factor for stroke and TIA, so screening for potential OSA and referral may be needed.15

Back to the Case

When Mr. G arrived at the ED, his symptoms had resolved. Based on the history of expressive aphasia and right-sided weakness, he most likely had a TIA in the left MCA territory. Hemorrhage was ruled out with a non-contrast head CT. His pacemaker precluded obtaining an MRI. CTA revealed diffuse atherosclerotic disease without evidence of carotid stenosis. His ABCD2 score was six given his age, blood pressure, weakness, and symptom duration, and he was admitted for an expedited workup. His sodium and glucose were within normal limits. His hemoglobin A1c was 6.5%, his LDL was 120, and his international normalized ratio (INR) was therapeutic at 2.1. His TIA may have been due to AF, despite a therapeutic INR, because warfarin does not fully eliminate the stroke risk. It might also have been caused by intracranial atherosclerosis.

Two days later, the patient was discharged on atorvastatin at 80 mg, and his lisinopril was increased for blood pressure control. For his age group, A1c of 6.5% was acceptable, and he was not initiated on glycemic control.

Bottom Line

TIAs are diagnosed based on patient history. Urgent initiation of secondary prevention is important to reduce the short-term risk of stroke and should be implemented by the time of discharge from the hospital.

Dr. Zeng is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, and Dr. Douglas is associate professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco.

References

- Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2276-2293.

- Sundararajan V, Thrift AG, Phan TG, Choi PM, Clissold B, Srikanth VK. Trends over time in the risk of stroke after an incident transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2014;45(11):3214-3218.

- Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, et al. Transient ischemic attack–proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1713-1716.

- Grysiewicz RA, Thomas K, Pandey DK. Epidemiology of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: incidence, prevalence, mortality, and risk factors. Neurol Clin. 2008;26(4):871-895, vii.

- Johnston SC, Sidney S, Bernstein AL, Gress DR. A comparison of risk factors for recurrent TIA and stroke in patients diagnosed with TIA. Neurology. 2003;60(2):280-285.

- Tsivgoulis G, Stamboulis E, Sharma VK, et al. Multicenter external validation of the ABCD2 score in triaging TIA patients. Neurology. 2010;74(17):1351-1357.

- Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283-292.

- Nguyen-Huynh MN, Johnston SC. Is hospitalization after TIA cost-effective on the basis of treatment with tPA? Neurology. 2005;65(11):1799-1801.

- Douglas VC, Johnston CM, Elkins J, Sidney S, Gress DR, Johnston SC. Head computed tomography findings predict short-term stroke risk after transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2003;34(12):2894-2898.

- Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Addition of brain infarction to the ABCD2 Score (ABCD2I): a collaborative analysis of unpublished data on 4574 patients. Stroke. 2010;41(9):1907-1913.

- Lanzino G, Rabinstein AA, Brown RD Jr. Treatment of carotid artery stenosis: medical therapy, surgery, or stenting? Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(4):362-387; quiz 367-368.

- Gladstone DJ, Spring M, Dorian P, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(26):2467-2477.

- Lavallée PC, Meseguer E, Abboud H, et al. A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(11):953-960.

- Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1432-1442.

- Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160-2236.

- Roumie CL, Zillich AJ, Bravata DM, et al. Hypertension treatment intensification among stroke survivors with uncontrolled blood pressure. Stroke. 2015;46(2):465-470.

- Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A, et al. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(6):549-559.

- Lennon O, Galvin R, Smith K, Doody C, Blake C. Lifestyle interventions for secondary disease prevention in stroke and transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(8):1026-1039.

Case

Mr. G is an 80-year-old man with a pacemaker, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation (AF) on warfarin, and tachy-brady syndrome. He presented after experiencing episodes in which he was unable to speak and had weakness on his right side. He had a normal neurological exam upon arrival to the ED, and his blood pressure was 160/80 mm Hg.

Overview

Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) are brief interruptions in brain perfusion that do not result in permanent neurologic damage. Up to half a million TIAs occur each year in the U.S., and they account for one third of acute cerebrovascular disease.1 While the term suggests that TIAs are benign, they are in fact an important warning sign of impending stroke and are essentially analogous to unstable angina. Some 10% of TIAs convert to full strokes within 90 days, but growing evidence suggests appropriate interventions can decrease this risk to 3%.2

Unfortunately, the symptoms of TIA have usually resolved by the time patients arrive at the hospital, which makes them challenging to diagnose. This article provides a summary of how to diagnose TIA accurately, using a focused history informed by cerebrovascular localization; how to triage, evaluate, and risk stratify patients; and how to implement preventative strategies.

Review of the Data

Classically, TIAs are defined as lasting less than 24 hours; however, 24 hours is an arbitrary number, and most TIAs last less than one hour.1 Furthermore, this definition has evolved with advances in neuroimaging that reveal that up to 50% of classically defined TIAs have evidence of infarct on MRI.1 There is no absolute temporal cut-off after which infarct is always seen on MRI, but longer duration of symptoms correlates with a higher likelihood of infarct. To reconcile these observations, a recently proposed definition stipulates that a true TIA lasts no more than one hour and does not show evidence of infarct on MRI.3

The causes of TIA are identical to those for ischemic stroke. Cerebral ischemia can result from an embolus, arterial thrombosis, or hypoperfusion due to arterial stenosis. Emboli can be cardiac, most commonly due to AF, or non-cardiac, stemming from a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque in the aortic arch, the carotid or vertebral artery, or an intracranial vessel. Atherosclerotic disease in the carotid arteries or intracranial vessels can also lead to thrombosis and occlusion or flow-related TIAs as a result of severe stenosis.

Risk factors for TIA mirror those for heart disease. Non-modifiable risk factors include older age, black race, male sex, and family history of stroke. Modifiable factors include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, tobacco smoking, diabetes, and AF.4

Most of the time, patients’ symptoms will have resolved by the time they are evaluated by a physician. Therefore, the diagnosis of TIA relies almost exclusively on the patient history. Eliciting a good history helps physicians determine whether the episode of transient neurologic dysfunction was caused by cerebral ischemia, as opposed to another mechanism, such as migraine or seizure. This calls for a basic understanding of cerebrovascular anatomy (see Table 1).

Types of Ischemia

Anterior cerebral artery ischemia causes contralateral leg weakness because it supplies the medial frontal and parietal lobes, where the legs in the sensorimotor homunculus are represented. Middle cerebral artery (MCA) ischemia causes contralateral face and arm weakness out of proportion to leg weakness. Ischemia in Broca’s area of the brain, which is supplied by the left MCA, may also cause expressive aphasia. Transient monocular blindness is a TIA of the retina due to atheroemboli originating from the internal carotid artery. Vertebrobasilar TIA is less common than anterior circulation TIA and manifests with brainstem symptoms that include diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, vertigo, gait imbalance, and weakness. In general, language and motor symptoms are more specific for cerebral ischemia and therefore more worrisome for TIA than sensory symptoms.5

Once a clinical diagnosis of TIA is made, an ABCD2 score (age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of TIA, presence of diabetes) can be used to predict the short-term risk of subsequent stroke (see Table 2).6,7 A general rule of thumb is to admit patients who present within 72 hours of the event and have an ABCD2 score of three or higher for observation, work-up, and initiation of secondary prevention.1

Although only a small percentage of patients with TIA will have a stroke during the period of observation in the hospital, this approach may be cost effective based on the assumption that hospitalized patients are more likely to receive intravenous tissue plasminogen activator.8 The decision should also be guided by clinical judgment. It is reasonable to admit a patient whose diagnostic workup cannot be rapidly completed.1

The workup for TIA includes routine labs, EKG with cardiac monitoring, and brain imaging. Labs are useful to evaluate for other mimics of TIA such as hyponatremia and glucose abnormalities. In addition, risk factors such as hyperlipidemia and diabetes should be evaluated with fasting lipid panel and blood glucose. The purpose of EKG and telemetry is to identify MI and capture paroxysmal AF. The goal of imaging is to ascertain the presence of vascular disease and to exclude a non-ischemic etiology. While less likely to cause transient neurologic symptoms, a hemorrhagic event must be ruled out, as it would trigger a different management pathway.

Imaging for TIA

There are two primary modes of brain imaging: computed tomography (CT) and MRI. Most patients who are suspected to have had a TIA undergo CT scan, and an infarct is seen about 20% of the time.1 The presence of an infarct usually correlates with the duration of symptoms and has prognostic value. In one study, a new infarct was associated with four times higher risk of stroke in the subsequent 90 days.9 Diffusion-weighted imaging, an MR-based technique, is the preferred modality when it is available because of its higher sensitivity and specificity for identifying acute lesions.1 In an international and multicenter study, incorporating imaging data increased the discriminatory power of stroke prediction.10

Extracranial imaging is mandatory to rule out carotid stenosis as a potential etiology of TIA. The least invasive modality is ultrasound, which can detect carotid stenosis with a sensitivity and specificity approaching 80%.1 While both the intra- and extracranial vasculature can be concurrently assessed using MR- or CT-angiography (CTA), this is not usually necessary in the acute setting, because only detecting carotid stenosis will result in a management change.1

Carotid endarterectomy is standard for symptomatic patients with greater than 70% stenosis and is a consideration for symptomatic patients with greater than 50% stenosis if it is the most probable explanation for the ischemic event.11 Despite a comprehensive workup, about 50% of TIA cases remain cryptogenic.12 In some of these patients, AF can be detected using extended ambulatory cardiac monitoring.12

The goal of admitting high-risk patients is to expedite workup and initiate therapy. Two studies have shown that immediate initiation of preventative treatment significantly reduces the risk of stroke by as much as 80%.13,14 Unless there is a specific indication for anticoagulation, all TIA patients should be started on an antiplatelet agent such as aspirin or clopidogrel. A large randomized trial conducted in China and published in 2013 demonstrated that dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for 21 days, followed by clopidogrel monotherapy, reduced the risk of stroke compared to aspirin monotherapy. An international multicenter trial designed to test the efficacy of short-term dual antiplatelet therapy is ongoing, and if the benefit of this approach is confirmed, this will likely become the standard of care. Evidence-based indications for anticoagulation after TIA are restricted to AF and mural thrombus in the setting of recent MI. Patients with implanted mechanical devices, including left ventricular assist devices and metal heart valves, should also receive anticoagulation.15

Risk factors should also be targeted in every case. Hypertension should be treated with a goal of lower than 140/90 mm Hg (or 130/80 mm Hg in diabetics and those with renal disease). Studies have shown that patients who are discharged with a blood pressure lower than 140/90 mm Hg are more likely to maintain this blood pressure at one-year follow-up.16 The choice of medication is less well studied, but drugs that act on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and thiazides are generally preferred.15 Treatment with a statin is recommended after cerebrovascular ischemic events, with a goal LDL under 100. This reduces risk of secondary stroke by about 20%.17

At discharge, it is also important to counsel patients on their role in preventing strokes. As with many diseases, making lifestyle changes is key to stroke prevention. Encourage smoking cessation and an increase in physical activity, and discourage heavy alcohol use. The association between smoking and the risk for first stroke is well established. Moderate to high-intensity exercise can reduce secondary stroke risk by as much as 50%18 (see Table 3). While light alcohol consumption can be protective against strokes, heavy use is strongly discouraged. Emerging data suggest obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may be another modifiable risk factor for stroke and TIA, so screening for potential OSA and referral may be needed.15

Back to the Case

When Mr. G arrived at the ED, his symptoms had resolved. Based on the history of expressive aphasia and right-sided weakness, he most likely had a TIA in the left MCA territory. Hemorrhage was ruled out with a non-contrast head CT. His pacemaker precluded obtaining an MRI. CTA revealed diffuse atherosclerotic disease without evidence of carotid stenosis. His ABCD2 score was six given his age, blood pressure, weakness, and symptom duration, and he was admitted for an expedited workup. His sodium and glucose were within normal limits. His hemoglobin A1c was 6.5%, his LDL was 120, and his international normalized ratio (INR) was therapeutic at 2.1. His TIA may have been due to AF, despite a therapeutic INR, because warfarin does not fully eliminate the stroke risk. It might also have been caused by intracranial atherosclerosis.

Two days later, the patient was discharged on atorvastatin at 80 mg, and his lisinopril was increased for blood pressure control. For his age group, A1c of 6.5% was acceptable, and he was not initiated on glycemic control.

Bottom Line

TIAs are diagnosed based on patient history. Urgent initiation of secondary prevention is important to reduce the short-term risk of stroke and should be implemented by the time of discharge from the hospital.

Dr. Zeng is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, and Dr. Douglas is associate professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco.

References

- Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2276-2293.

- Sundararajan V, Thrift AG, Phan TG, Choi PM, Clissold B, Srikanth VK. Trends over time in the risk of stroke after an incident transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2014;45(11):3214-3218.

- Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, et al. Transient ischemic attack–proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1713-1716.

- Grysiewicz RA, Thomas K, Pandey DK. Epidemiology of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: incidence, prevalence, mortality, and risk factors. Neurol Clin. 2008;26(4):871-895, vii.

- Johnston SC, Sidney S, Bernstein AL, Gress DR. A comparison of risk factors for recurrent TIA and stroke in patients diagnosed with TIA. Neurology. 2003;60(2):280-285.

- Tsivgoulis G, Stamboulis E, Sharma VK, et al. Multicenter external validation of the ABCD2 score in triaging TIA patients. Neurology. 2010;74(17):1351-1357.

- Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283-292.

- Nguyen-Huynh MN, Johnston SC. Is hospitalization after TIA cost-effective on the basis of treatment with tPA? Neurology. 2005;65(11):1799-1801.

- Douglas VC, Johnston CM, Elkins J, Sidney S, Gress DR, Johnston SC. Head computed tomography findings predict short-term stroke risk after transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2003;34(12):2894-2898.

- Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Addition of brain infarction to the ABCD2 Score (ABCD2I): a collaborative analysis of unpublished data on 4574 patients. Stroke. 2010;41(9):1907-1913.

- Lanzino G, Rabinstein AA, Brown RD Jr. Treatment of carotid artery stenosis: medical therapy, surgery, or stenting? Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(4):362-387; quiz 367-368.

- Gladstone DJ, Spring M, Dorian P, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(26):2467-2477.

- Lavallée PC, Meseguer E, Abboud H, et al. A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(11):953-960.

- Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1432-1442.

- Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160-2236.

- Roumie CL, Zillich AJ, Bravata DM, et al. Hypertension treatment intensification among stroke survivors with uncontrolled blood pressure. Stroke. 2015;46(2):465-470.