User login

Lanolin: The 2023 American Contact Dermatitis Society Allergen of the Year

Lanolin was announced as the Allergen of the Year by the American Contact Dermatitis Society in March 2023.1 However, allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to lanolin remains a matter of fierce debate among dermatologists. Herein, we discuss this important contact allergen, emphasizing the controversy behind its allergenicity and nuances to consider when patch testing.

What is Lanolin?

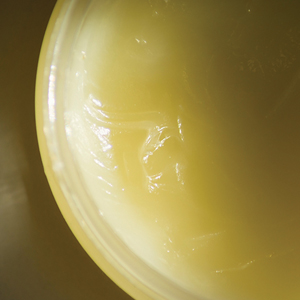

Lanolin is a greasy, yellow, fatlike substance derived from the sebaceous glands of sheep. It is extracted from wool using an intricate process of scouring with dilute alkali, centrifuging, and refining with hot alkali and bleach.2 It is comprised of a complex mixture of esters, alcohols, sterols, fatty acids, lactose, and hydrocarbons.3

The hydrophobic property of lanolin helps sheep shed water from their coats.3 In humans, this hydrophobicity benefits the skin by retaining moisture already present in the epidermis. Lanolin can hold as much as twice its weight in water and may reduce transepidermal water loss by 20% to 30%.4-6 In addition, lanolin maintains tissue breathability, which supports proper gas exchange, promoting wound healing and protecting against infection.3,7

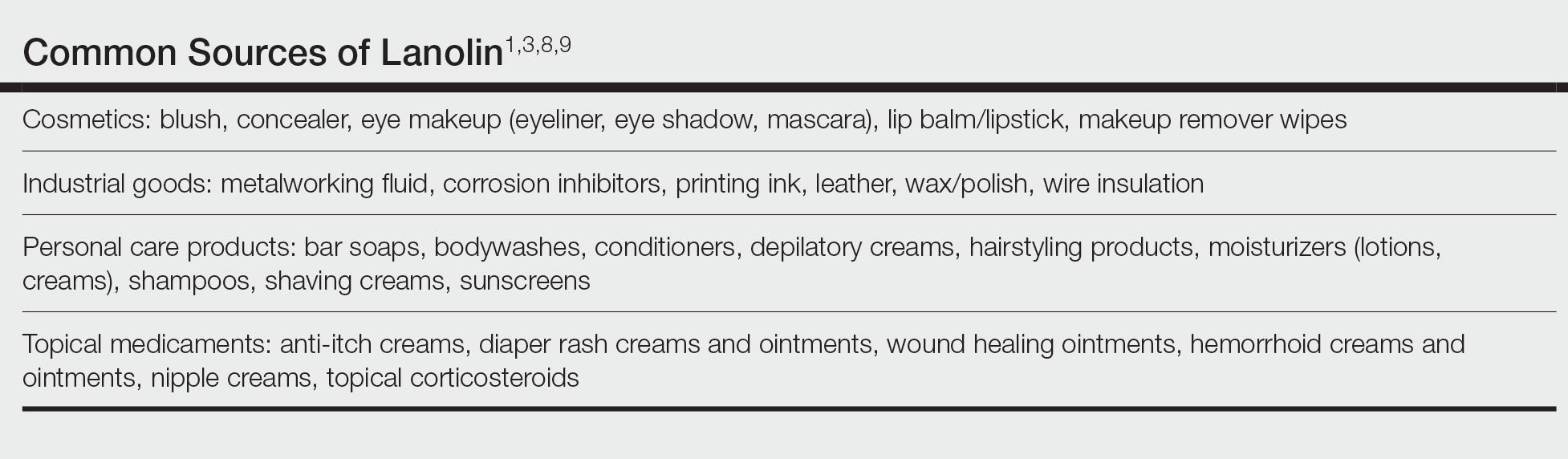

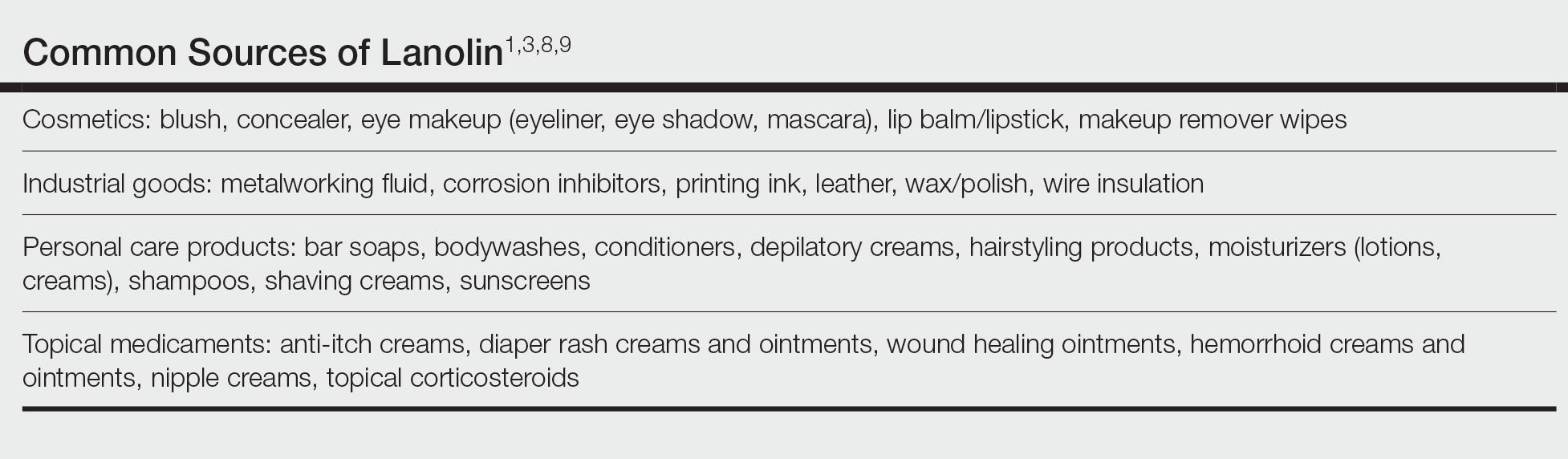

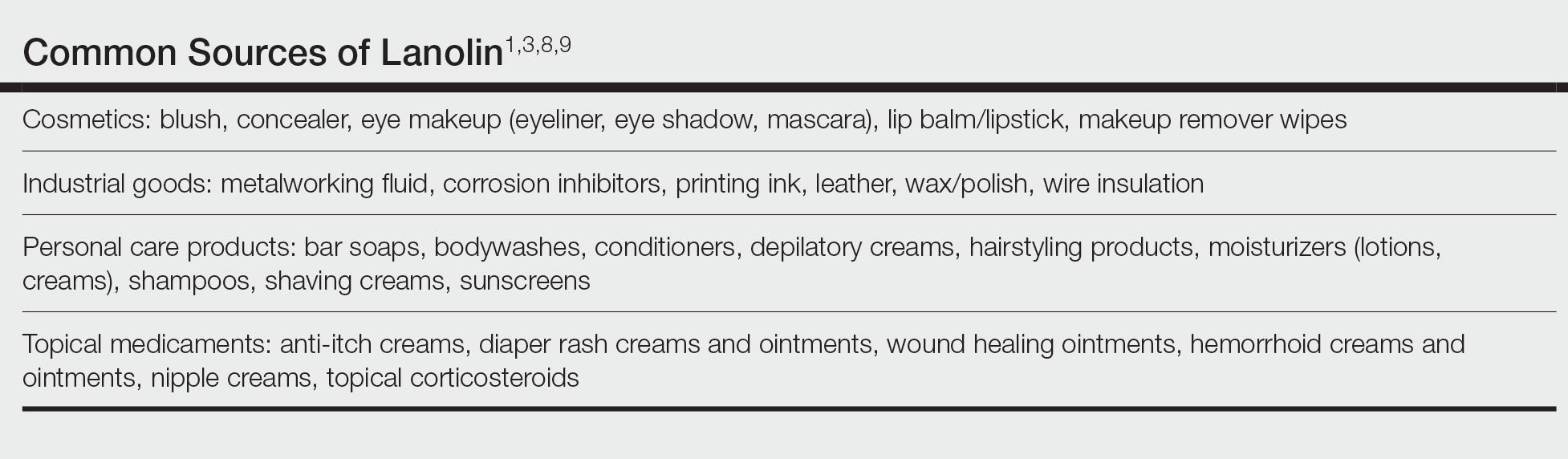

Many personal care products (PCPs), cosmetics, and topical medicaments contain lanolin, particularly products marketed to help restore dry cracked skin. The range of permitted concentrations of lanolin in over-the-counter products in the United States is 12.5% to 50%.3 Lanolin also may be found in industrial goods. The Table provides a comprehensive list of common items that may contain lanolin.1,3,8,9

A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing?

Despite its benefits, lanolin is a potential source of ACD. The first reported positive patch test (PPT) to lanolin worldwide was in the late 1920s.10 Subsequent cases of ACD to lanolin were described over the next 30 years, reaching a peak of recognition in the latter half of the 20th century with rates of PPT ranging from 0% to 7.4%, though the patient population and lanolin patch-test formulation used differed across studies.9 The North American Contact Dermatitis Group observed that 3.3% (1431/43,691) of patients tested from 2001 to 2018 had a PPT to either lanolin alcohol 30% in petrolatum (pet) or Amerchol L101 (10% lanolin alcohol dissolved in mineral oil) 50% pet.11 Compared to patients referred for patch testing, the prevalence of contact allergy to lanolin is lower in the general population; 0.4% of the general population in Europe (N=3119) tested positive to wool alcohols 1.0 mg/cm2 on the thin-layer rapid use Epicutaneous (TRUE) test.12

Allergic contact dermatitis to lanolin is unrelated to an allergy to wool itself, which probably does not exist, though wool is well known to cause irritant contact dermatitis, particularly in atopic individuals.13

Who Is at Risk for Lanolin Allergy?

In a recent comprehensive review of lanolin allergy, Jenkins and Belsito1 summarized 4 high-risk subgroups of patients for the development of lanolin contact allergy: stasis dermatitis, chronic leg ulcers, atopic dermatitis (AD), and perianal/genital dermatitis. These chronic inflammatory skin conditions may increase the risk for ACD to lanolin via increased exposure in topical therapies and/or increased allergen penetration through an impaired epidermal barrier.14-16 Demographically, older adults and children are at-risk groups, likely secondary to the higher prevalence of stasis dermatitis/leg ulcers in the former group and AD in the latter.1

Lanolin Controversies

The allergenicity of lanolin is far from straightforward. In 1996, Wolf17 first described the “lanolin paradox,” modeled after the earlier “paraben paradox” described by Fisher.18 There are 4 clinical phenomena of the lanolin paradox17:

- Lanolin generally does not cause contact allergy when found in PCPs but may cause ACD when found in topical medicaments.

- Some patients can use lanolin-containing PCPs on healthy skin without issue but will develop ACD when a lanolin-containing topical medicament is applied to inflamed skin. This is because inflamed skin is more easily sensitized.

- False-negative patch test reactions to pure lanolin may occur. Since Wolf’s17 initial description of the paradox, free alcohols of lanolin have been found to be its principal allergen, though it also is possible that oxidation of lanolin could generate additional allergenic substances.1

- Patch testing with wool alcohol 30% can generate both false-negative and false-positive results.

At one extreme, Kligman19 also was concerned about false-positive reactions to lanolin, describing lanolin allergy as a myth attributed to overzealous patch testing and a failure to appreciate the limitations of this diagnostic modality. Indeed, just having a PPT to lanolin (ie, contact allergy) does not automatically translate to a relevant ACD,1 and determining the clinical relevance of a PPT is of utmost importance. In 2001, Wakelin et al20 reported that the majority (71% [92/130]) of positive reactions to Amerchol L101 50% or 100% pet showed current clinical relevance. Data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group in 2009 and in 2022 were similar, with 83.4% (529/634) of positive reactions to lanolin alcohol 30% pet and 86.5% (1238/1431) of positive reactions to Amerchol L101 50% pet classified as current clinical relevance.11,21 These findings demonstrate that although lanolin may be a weak sensitizer, a PPT usually represents a highly relevant cause of dermatitis.

Considerations for Patch Testing

Considering Wolf’s17 claim that even pure lanolin is not an appropriate formulation to use for patch testing due to the risk for inaccurate results, you might now be wondering which preparation should be used. Mortensen22 popularized another compound, Amerchol L101, in 1979. In this small study of 60 patients with a PPT to lanolin and/or its derivatives, the highest proportion (37% [22/60]) were positive to Amerchol L101 but negative to wool alcohol 30%, suggesting the need to test to more than one preparation simultaneously.22 In a larger study by Miest et al,23 3.9% (11/268) of patients had a PPT to Amerchol L101 50% pet, whereas only 1.1% (3/268) had a PPT to lanolin alcohol 30% pet. This highlighted the importance of including Amerchol L101 when patch testing because it was thought to capture more positive results; however, some studies suggest that Amerchol L101 is not superior at predicting lanolin contact allergy vs lanolin alcohol 30% pet. The risk for an irritant reaction when patch testing with Amerchol L101 should be considered due to its mineral oil component.24

Although there is no universal consensus to date, some investigators suggest patch testing both lanolin alcohol 30% pet and Amerchol L101 50% pet simultaneously.1 The TRUE test utilizes 1000 µg/cm2 of wool alcohols, while the North American 80 Comprehensive Series and the American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 90 Series contain Amerchol L101 50% pet. Patch testing to the most allergenic component of lanolin—the free fatty alcohols (particularly alkane-α,β-diols and alkane-α,ω-diols)—has been suggested,1 though these formulations are not yet commercially available.

When available, the patient’s own lanolin-containing PCPs should be tested.1 Performing a repeat open application test (ROAT) to a lanolin-containing product also may be highly useful to distinguish weak-positive from irritant patch test reactions and to determine if sensitized patients can tolerate lanolin-containing products on intact skin. To complete a ROAT, a patient should apply the suspected leave-on product to a patch of unaffected skin (classically the volar forearm) twice daily for at least 10 days.25 If the application site is clear after 10 days, the patient is unlikely to have ACD to the product in question. Compared to patch testing, ROAT more accurately mimics a true use situation, which is particularly important for lanolin given its tendency to preferentially impact damaged or inflamed skin while sparing healthy skin.

Alternatives to Lanolin

Patients with confirmed ACD to lanolin may use plain petrolatum, a safe and inexpensive substitute with equivalent moisturizing efficacy. It can reduce transepidermal water loss by more than 98%,4 with essentially no risk for ACD. Humectants such as glycerin, sorbitol, and α-hydroxy acids also have moisturizing properties akin to those of lanolin. In addition, some oils may provide benefit to patients with chronic skin conditions. Sunflower seed oil and extra virgin coconut oil have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and barrier repair properties.26,27 Allergic contact dermatitis to these oils rarely, if ever, occurs.28

Final Interpretation

Lanolin is a well-known yet controversial contact allergen that is widely used in PCPs, cosmetics, topical medicaments, and industrial goods. Lanolin ACD preferentially impacts patients with stasis dermatitis, chronic leg ulcers, AD, and perianal/genital dermatitis. Patch testing with more than one lanolin formulation, including lanolin alcohol 30% pet and/or Amerchol L101 50% pet, as well as testing the patient’s own products may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. In cases of ACD to lanolin, an alternative agent, such as plain petrolatum, may be used.

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089/derm.2022.0002

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (2023). PubChem Annotation Record for LANOLIN, Source: Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB). Accessed July 21, 2023. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/source/hsdb/1817

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem compound summary lanolin. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Lanolin

- Purnamawati S, Indrastuti N, Danarti R, et al. the role of moisturizers in addressing various kinds of dermatitis: a review. Clin Med Res. 2017;15:75-87. doi:10.3121/cmr.2017.1363

- Sethi A, Kaur T, Malhotra SK, et al. Moisturizers: the slippery road. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:279-287. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.182427

- Souto EB, Yoshida CMP, Leonardi GR, et al. Lipid-polymeric films: composition, production and applications in wound healing and skin repair. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:1199. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13081199

- Rüther L, Voss W. Hydrogel or ointment? comparison of five different galenics regarding tissue breathability and transepidermal water loss. Heliyon. 2021;7:E06071. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06071

- Zirwas MJ. Contact alternatives and the internet. Dermatitis. 2012;23:192-194. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e31826ea0d2

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Ramirez M, Eller JJ. The patch test in contact dermatitis. Allergy. 1929;1:489-493.

- Silverberg JI, Patel N, Warshaw EM, et al. Lanolin allergic reactions: North American Contact Dermatitis Group experience, 2001 to 2018. Dermatitis. 2022;33:193-199. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000871

- Diepgen TL, Ofenloch RF, Bruze M, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population in different European regions. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:319-329. doi:10.1111/bjd.14167

- Zallmann M, Smith PK, Tang MLK, et al. Debunking the myth of wool allergy: reviewing the evidence for immune and non-immune cutaneous reactions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:906-915. doi:10.2340/00015555-2655

- Yosipovitch G, Nedorost ST, Silverberg JI, et al. Stasis dermatitis: an overview of its clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:275-286. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00753-5

- Johnson H, Novack DE, Adler BL, et al. Can atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis coexist? Cutis. 2022;110:139-142. doi:10.12788/cutis.0599

- Gilissen L, Schollaert I, Huygens S, et al. Iatrogenic allergic contact dermatitis in the (peri)anal and genital area. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84:431-438. doi:10.1111/cod.13764

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Fisher AA. The paraben paradox. Cutis. 1973;12:830-832.

- Kligman AM. The myth of lanolin allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:103-107. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05856.x

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

- Warshaw EM, Nelsen DD, Maibach HI, et al. Positive patch test reactions to lanolin: cross-sectional data from the North American Contact Dermatitis group, 1994 to 2006. Dermatitis. 2009;20:79-88.

- Mortensen T. Allergy to lanolin. Contact Dermatitis. 1979;5:137-139. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1979.tb04824.x

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Amsler E, Assier H, Soria A, et al. What is the optimal duration for a ROAT? the experience of the French Dermatology and Allergology group (DAG). Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:170-175. doi:10.1111/cod.14118

- Msika P, De Belilovsky C, Piccardi N, et al. New emollient with topical corticosteroid-sparing effect in treatment of childhood atopic dermatitis: SCORAD and quality of life improvement. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:606-612. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00783.x

- Lio PA. Alternative therapies in atopic dermatitis care: part 2. Pract Dermatol. July 2011:48-50.

- Karagounis TK, Gittler JK, Rotemberg V, et al. Use of “natural” oils for moisturization: review of olive, coconut, and sunflower seed oil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:9-15. doi:10.1111/pde.13621

Lanolin was announced as the Allergen of the Year by the American Contact Dermatitis Society in March 2023.1 However, allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to lanolin remains a matter of fierce debate among dermatologists. Herein, we discuss this important contact allergen, emphasizing the controversy behind its allergenicity and nuances to consider when patch testing.

What is Lanolin?

Lanolin is a greasy, yellow, fatlike substance derived from the sebaceous glands of sheep. It is extracted from wool using an intricate process of scouring with dilute alkali, centrifuging, and refining with hot alkali and bleach.2 It is comprised of a complex mixture of esters, alcohols, sterols, fatty acids, lactose, and hydrocarbons.3

The hydrophobic property of lanolin helps sheep shed water from their coats.3 In humans, this hydrophobicity benefits the skin by retaining moisture already present in the epidermis. Lanolin can hold as much as twice its weight in water and may reduce transepidermal water loss by 20% to 30%.4-6 In addition, lanolin maintains tissue breathability, which supports proper gas exchange, promoting wound healing and protecting against infection.3,7

Many personal care products (PCPs), cosmetics, and topical medicaments contain lanolin, particularly products marketed to help restore dry cracked skin. The range of permitted concentrations of lanolin in over-the-counter products in the United States is 12.5% to 50%.3 Lanolin also may be found in industrial goods. The Table provides a comprehensive list of common items that may contain lanolin.1,3,8,9

A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing?

Despite its benefits, lanolin is a potential source of ACD. The first reported positive patch test (PPT) to lanolin worldwide was in the late 1920s.10 Subsequent cases of ACD to lanolin were described over the next 30 years, reaching a peak of recognition in the latter half of the 20th century with rates of PPT ranging from 0% to 7.4%, though the patient population and lanolin patch-test formulation used differed across studies.9 The North American Contact Dermatitis Group observed that 3.3% (1431/43,691) of patients tested from 2001 to 2018 had a PPT to either lanolin alcohol 30% in petrolatum (pet) or Amerchol L101 (10% lanolin alcohol dissolved in mineral oil) 50% pet.11 Compared to patients referred for patch testing, the prevalence of contact allergy to lanolin is lower in the general population; 0.4% of the general population in Europe (N=3119) tested positive to wool alcohols 1.0 mg/cm2 on the thin-layer rapid use Epicutaneous (TRUE) test.12

Allergic contact dermatitis to lanolin is unrelated to an allergy to wool itself, which probably does not exist, though wool is well known to cause irritant contact dermatitis, particularly in atopic individuals.13

Who Is at Risk for Lanolin Allergy?

In a recent comprehensive review of lanolin allergy, Jenkins and Belsito1 summarized 4 high-risk subgroups of patients for the development of lanolin contact allergy: stasis dermatitis, chronic leg ulcers, atopic dermatitis (AD), and perianal/genital dermatitis. These chronic inflammatory skin conditions may increase the risk for ACD to lanolin via increased exposure in topical therapies and/or increased allergen penetration through an impaired epidermal barrier.14-16 Demographically, older adults and children are at-risk groups, likely secondary to the higher prevalence of stasis dermatitis/leg ulcers in the former group and AD in the latter.1

Lanolin Controversies

The allergenicity of lanolin is far from straightforward. In 1996, Wolf17 first described the “lanolin paradox,” modeled after the earlier “paraben paradox” described by Fisher.18 There are 4 clinical phenomena of the lanolin paradox17:

- Lanolin generally does not cause contact allergy when found in PCPs but may cause ACD when found in topical medicaments.

- Some patients can use lanolin-containing PCPs on healthy skin without issue but will develop ACD when a lanolin-containing topical medicament is applied to inflamed skin. This is because inflamed skin is more easily sensitized.

- False-negative patch test reactions to pure lanolin may occur. Since Wolf’s17 initial description of the paradox, free alcohols of lanolin have been found to be its principal allergen, though it also is possible that oxidation of lanolin could generate additional allergenic substances.1

- Patch testing with wool alcohol 30% can generate both false-negative and false-positive results.

At one extreme, Kligman19 also was concerned about false-positive reactions to lanolin, describing lanolin allergy as a myth attributed to overzealous patch testing and a failure to appreciate the limitations of this diagnostic modality. Indeed, just having a PPT to lanolin (ie, contact allergy) does not automatically translate to a relevant ACD,1 and determining the clinical relevance of a PPT is of utmost importance. In 2001, Wakelin et al20 reported that the majority (71% [92/130]) of positive reactions to Amerchol L101 50% or 100% pet showed current clinical relevance. Data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group in 2009 and in 2022 were similar, with 83.4% (529/634) of positive reactions to lanolin alcohol 30% pet and 86.5% (1238/1431) of positive reactions to Amerchol L101 50% pet classified as current clinical relevance.11,21 These findings demonstrate that although lanolin may be a weak sensitizer, a PPT usually represents a highly relevant cause of dermatitis.

Considerations for Patch Testing

Considering Wolf’s17 claim that even pure lanolin is not an appropriate formulation to use for patch testing due to the risk for inaccurate results, you might now be wondering which preparation should be used. Mortensen22 popularized another compound, Amerchol L101, in 1979. In this small study of 60 patients with a PPT to lanolin and/or its derivatives, the highest proportion (37% [22/60]) were positive to Amerchol L101 but negative to wool alcohol 30%, suggesting the need to test to more than one preparation simultaneously.22 In a larger study by Miest et al,23 3.9% (11/268) of patients had a PPT to Amerchol L101 50% pet, whereas only 1.1% (3/268) had a PPT to lanolin alcohol 30% pet. This highlighted the importance of including Amerchol L101 when patch testing because it was thought to capture more positive results; however, some studies suggest that Amerchol L101 is not superior at predicting lanolin contact allergy vs lanolin alcohol 30% pet. The risk for an irritant reaction when patch testing with Amerchol L101 should be considered due to its mineral oil component.24

Although there is no universal consensus to date, some investigators suggest patch testing both lanolin alcohol 30% pet and Amerchol L101 50% pet simultaneously.1 The TRUE test utilizes 1000 µg/cm2 of wool alcohols, while the North American 80 Comprehensive Series and the American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 90 Series contain Amerchol L101 50% pet. Patch testing to the most allergenic component of lanolin—the free fatty alcohols (particularly alkane-α,β-diols and alkane-α,ω-diols)—has been suggested,1 though these formulations are not yet commercially available.

When available, the patient’s own lanolin-containing PCPs should be tested.1 Performing a repeat open application test (ROAT) to a lanolin-containing product also may be highly useful to distinguish weak-positive from irritant patch test reactions and to determine if sensitized patients can tolerate lanolin-containing products on intact skin. To complete a ROAT, a patient should apply the suspected leave-on product to a patch of unaffected skin (classically the volar forearm) twice daily for at least 10 days.25 If the application site is clear after 10 days, the patient is unlikely to have ACD to the product in question. Compared to patch testing, ROAT more accurately mimics a true use situation, which is particularly important for lanolin given its tendency to preferentially impact damaged or inflamed skin while sparing healthy skin.

Alternatives to Lanolin

Patients with confirmed ACD to lanolin may use plain petrolatum, a safe and inexpensive substitute with equivalent moisturizing efficacy. It can reduce transepidermal water loss by more than 98%,4 with essentially no risk for ACD. Humectants such as glycerin, sorbitol, and α-hydroxy acids also have moisturizing properties akin to those of lanolin. In addition, some oils may provide benefit to patients with chronic skin conditions. Sunflower seed oil and extra virgin coconut oil have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and barrier repair properties.26,27 Allergic contact dermatitis to these oils rarely, if ever, occurs.28

Final Interpretation

Lanolin is a well-known yet controversial contact allergen that is widely used in PCPs, cosmetics, topical medicaments, and industrial goods. Lanolin ACD preferentially impacts patients with stasis dermatitis, chronic leg ulcers, AD, and perianal/genital dermatitis. Patch testing with more than one lanolin formulation, including lanolin alcohol 30% pet and/or Amerchol L101 50% pet, as well as testing the patient’s own products may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. In cases of ACD to lanolin, an alternative agent, such as plain petrolatum, may be used.

Lanolin was announced as the Allergen of the Year by the American Contact Dermatitis Society in March 2023.1 However, allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to lanolin remains a matter of fierce debate among dermatologists. Herein, we discuss this important contact allergen, emphasizing the controversy behind its allergenicity and nuances to consider when patch testing.

What is Lanolin?

Lanolin is a greasy, yellow, fatlike substance derived from the sebaceous glands of sheep. It is extracted from wool using an intricate process of scouring with dilute alkali, centrifuging, and refining with hot alkali and bleach.2 It is comprised of a complex mixture of esters, alcohols, sterols, fatty acids, lactose, and hydrocarbons.3

The hydrophobic property of lanolin helps sheep shed water from their coats.3 In humans, this hydrophobicity benefits the skin by retaining moisture already present in the epidermis. Lanolin can hold as much as twice its weight in water and may reduce transepidermal water loss by 20% to 30%.4-6 In addition, lanolin maintains tissue breathability, which supports proper gas exchange, promoting wound healing and protecting against infection.3,7

Many personal care products (PCPs), cosmetics, and topical medicaments contain lanolin, particularly products marketed to help restore dry cracked skin. The range of permitted concentrations of lanolin in over-the-counter products in the United States is 12.5% to 50%.3 Lanolin also may be found in industrial goods. The Table provides a comprehensive list of common items that may contain lanolin.1,3,8,9

A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing?

Despite its benefits, lanolin is a potential source of ACD. The first reported positive patch test (PPT) to lanolin worldwide was in the late 1920s.10 Subsequent cases of ACD to lanolin were described over the next 30 years, reaching a peak of recognition in the latter half of the 20th century with rates of PPT ranging from 0% to 7.4%, though the patient population and lanolin patch-test formulation used differed across studies.9 The North American Contact Dermatitis Group observed that 3.3% (1431/43,691) of patients tested from 2001 to 2018 had a PPT to either lanolin alcohol 30% in petrolatum (pet) or Amerchol L101 (10% lanolin alcohol dissolved in mineral oil) 50% pet.11 Compared to patients referred for patch testing, the prevalence of contact allergy to lanolin is lower in the general population; 0.4% of the general population in Europe (N=3119) tested positive to wool alcohols 1.0 mg/cm2 on the thin-layer rapid use Epicutaneous (TRUE) test.12

Allergic contact dermatitis to lanolin is unrelated to an allergy to wool itself, which probably does not exist, though wool is well known to cause irritant contact dermatitis, particularly in atopic individuals.13

Who Is at Risk for Lanolin Allergy?

In a recent comprehensive review of lanolin allergy, Jenkins and Belsito1 summarized 4 high-risk subgroups of patients for the development of lanolin contact allergy: stasis dermatitis, chronic leg ulcers, atopic dermatitis (AD), and perianal/genital dermatitis. These chronic inflammatory skin conditions may increase the risk for ACD to lanolin via increased exposure in topical therapies and/or increased allergen penetration through an impaired epidermal barrier.14-16 Demographically, older adults and children are at-risk groups, likely secondary to the higher prevalence of stasis dermatitis/leg ulcers in the former group and AD in the latter.1

Lanolin Controversies

The allergenicity of lanolin is far from straightforward. In 1996, Wolf17 first described the “lanolin paradox,” modeled after the earlier “paraben paradox” described by Fisher.18 There are 4 clinical phenomena of the lanolin paradox17:

- Lanolin generally does not cause contact allergy when found in PCPs but may cause ACD when found in topical medicaments.

- Some patients can use lanolin-containing PCPs on healthy skin without issue but will develop ACD when a lanolin-containing topical medicament is applied to inflamed skin. This is because inflamed skin is more easily sensitized.

- False-negative patch test reactions to pure lanolin may occur. Since Wolf’s17 initial description of the paradox, free alcohols of lanolin have been found to be its principal allergen, though it also is possible that oxidation of lanolin could generate additional allergenic substances.1

- Patch testing with wool alcohol 30% can generate both false-negative and false-positive results.

At one extreme, Kligman19 also was concerned about false-positive reactions to lanolin, describing lanolin allergy as a myth attributed to overzealous patch testing and a failure to appreciate the limitations of this diagnostic modality. Indeed, just having a PPT to lanolin (ie, contact allergy) does not automatically translate to a relevant ACD,1 and determining the clinical relevance of a PPT is of utmost importance. In 2001, Wakelin et al20 reported that the majority (71% [92/130]) of positive reactions to Amerchol L101 50% or 100% pet showed current clinical relevance. Data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group in 2009 and in 2022 were similar, with 83.4% (529/634) of positive reactions to lanolin alcohol 30% pet and 86.5% (1238/1431) of positive reactions to Amerchol L101 50% pet classified as current clinical relevance.11,21 These findings demonstrate that although lanolin may be a weak sensitizer, a PPT usually represents a highly relevant cause of dermatitis.

Considerations for Patch Testing

Considering Wolf’s17 claim that even pure lanolin is not an appropriate formulation to use for patch testing due to the risk for inaccurate results, you might now be wondering which preparation should be used. Mortensen22 popularized another compound, Amerchol L101, in 1979. In this small study of 60 patients with a PPT to lanolin and/or its derivatives, the highest proportion (37% [22/60]) were positive to Amerchol L101 but negative to wool alcohol 30%, suggesting the need to test to more than one preparation simultaneously.22 In a larger study by Miest et al,23 3.9% (11/268) of patients had a PPT to Amerchol L101 50% pet, whereas only 1.1% (3/268) had a PPT to lanolin alcohol 30% pet. This highlighted the importance of including Amerchol L101 when patch testing because it was thought to capture more positive results; however, some studies suggest that Amerchol L101 is not superior at predicting lanolin contact allergy vs lanolin alcohol 30% pet. The risk for an irritant reaction when patch testing with Amerchol L101 should be considered due to its mineral oil component.24

Although there is no universal consensus to date, some investigators suggest patch testing both lanolin alcohol 30% pet and Amerchol L101 50% pet simultaneously.1 The TRUE test utilizes 1000 µg/cm2 of wool alcohols, while the North American 80 Comprehensive Series and the American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 90 Series contain Amerchol L101 50% pet. Patch testing to the most allergenic component of lanolin—the free fatty alcohols (particularly alkane-α,β-diols and alkane-α,ω-diols)—has been suggested,1 though these formulations are not yet commercially available.

When available, the patient’s own lanolin-containing PCPs should be tested.1 Performing a repeat open application test (ROAT) to a lanolin-containing product also may be highly useful to distinguish weak-positive from irritant patch test reactions and to determine if sensitized patients can tolerate lanolin-containing products on intact skin. To complete a ROAT, a patient should apply the suspected leave-on product to a patch of unaffected skin (classically the volar forearm) twice daily for at least 10 days.25 If the application site is clear after 10 days, the patient is unlikely to have ACD to the product in question. Compared to patch testing, ROAT more accurately mimics a true use situation, which is particularly important for lanolin given its tendency to preferentially impact damaged or inflamed skin while sparing healthy skin.

Alternatives to Lanolin

Patients with confirmed ACD to lanolin may use plain petrolatum, a safe and inexpensive substitute with equivalent moisturizing efficacy. It can reduce transepidermal water loss by more than 98%,4 with essentially no risk for ACD. Humectants such as glycerin, sorbitol, and α-hydroxy acids also have moisturizing properties akin to those of lanolin. In addition, some oils may provide benefit to patients with chronic skin conditions. Sunflower seed oil and extra virgin coconut oil have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and barrier repair properties.26,27 Allergic contact dermatitis to these oils rarely, if ever, occurs.28

Final Interpretation

Lanolin is a well-known yet controversial contact allergen that is widely used in PCPs, cosmetics, topical medicaments, and industrial goods. Lanolin ACD preferentially impacts patients with stasis dermatitis, chronic leg ulcers, AD, and perianal/genital dermatitis. Patch testing with more than one lanolin formulation, including lanolin alcohol 30% pet and/or Amerchol L101 50% pet, as well as testing the patient’s own products may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. In cases of ACD to lanolin, an alternative agent, such as plain petrolatum, may be used.

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089/derm.2022.0002

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (2023). PubChem Annotation Record for LANOLIN, Source: Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB). Accessed July 21, 2023. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/source/hsdb/1817

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem compound summary lanolin. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Lanolin

- Purnamawati S, Indrastuti N, Danarti R, et al. the role of moisturizers in addressing various kinds of dermatitis: a review. Clin Med Res. 2017;15:75-87. doi:10.3121/cmr.2017.1363

- Sethi A, Kaur T, Malhotra SK, et al. Moisturizers: the slippery road. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:279-287. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.182427

- Souto EB, Yoshida CMP, Leonardi GR, et al. Lipid-polymeric films: composition, production and applications in wound healing and skin repair. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:1199. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13081199

- Rüther L, Voss W. Hydrogel or ointment? comparison of five different galenics regarding tissue breathability and transepidermal water loss. Heliyon. 2021;7:E06071. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06071

- Zirwas MJ. Contact alternatives and the internet. Dermatitis. 2012;23:192-194. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e31826ea0d2

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Ramirez M, Eller JJ. The patch test in contact dermatitis. Allergy. 1929;1:489-493.

- Silverberg JI, Patel N, Warshaw EM, et al. Lanolin allergic reactions: North American Contact Dermatitis Group experience, 2001 to 2018. Dermatitis. 2022;33:193-199. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000871

- Diepgen TL, Ofenloch RF, Bruze M, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population in different European regions. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:319-329. doi:10.1111/bjd.14167

- Zallmann M, Smith PK, Tang MLK, et al. Debunking the myth of wool allergy: reviewing the evidence for immune and non-immune cutaneous reactions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:906-915. doi:10.2340/00015555-2655

- Yosipovitch G, Nedorost ST, Silverberg JI, et al. Stasis dermatitis: an overview of its clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:275-286. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00753-5

- Johnson H, Novack DE, Adler BL, et al. Can atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis coexist? Cutis. 2022;110:139-142. doi:10.12788/cutis.0599

- Gilissen L, Schollaert I, Huygens S, et al. Iatrogenic allergic contact dermatitis in the (peri)anal and genital area. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84:431-438. doi:10.1111/cod.13764

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Fisher AA. The paraben paradox. Cutis. 1973;12:830-832.

- Kligman AM. The myth of lanolin allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:103-107. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05856.x

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

- Warshaw EM, Nelsen DD, Maibach HI, et al. Positive patch test reactions to lanolin: cross-sectional data from the North American Contact Dermatitis group, 1994 to 2006. Dermatitis. 2009;20:79-88.

- Mortensen T. Allergy to lanolin. Contact Dermatitis. 1979;5:137-139. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1979.tb04824.x

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Amsler E, Assier H, Soria A, et al. What is the optimal duration for a ROAT? the experience of the French Dermatology and Allergology group (DAG). Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:170-175. doi:10.1111/cod.14118

- Msika P, De Belilovsky C, Piccardi N, et al. New emollient with topical corticosteroid-sparing effect in treatment of childhood atopic dermatitis: SCORAD and quality of life improvement. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:606-612. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00783.x

- Lio PA. Alternative therapies in atopic dermatitis care: part 2. Pract Dermatol. July 2011:48-50.

- Karagounis TK, Gittler JK, Rotemberg V, et al. Use of “natural” oils for moisturization: review of olive, coconut, and sunflower seed oil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:9-15. doi:10.1111/pde.13621

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089/derm.2022.0002

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (2023). PubChem Annotation Record for LANOLIN, Source: Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB). Accessed July 21, 2023. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/source/hsdb/1817

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem compound summary lanolin. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Lanolin

- Purnamawati S, Indrastuti N, Danarti R, et al. the role of moisturizers in addressing various kinds of dermatitis: a review. Clin Med Res. 2017;15:75-87. doi:10.3121/cmr.2017.1363

- Sethi A, Kaur T, Malhotra SK, et al. Moisturizers: the slippery road. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:279-287. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.182427

- Souto EB, Yoshida CMP, Leonardi GR, et al. Lipid-polymeric films: composition, production and applications in wound healing and skin repair. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:1199. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13081199

- Rüther L, Voss W. Hydrogel or ointment? comparison of five different galenics regarding tissue breathability and transepidermal water loss. Heliyon. 2021;7:E06071. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06071

- Zirwas MJ. Contact alternatives and the internet. Dermatitis. 2012;23:192-194. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e31826ea0d2

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Ramirez M, Eller JJ. The patch test in contact dermatitis. Allergy. 1929;1:489-493.

- Silverberg JI, Patel N, Warshaw EM, et al. Lanolin allergic reactions: North American Contact Dermatitis Group experience, 2001 to 2018. Dermatitis. 2022;33:193-199. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000871

- Diepgen TL, Ofenloch RF, Bruze M, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population in different European regions. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:319-329. doi:10.1111/bjd.14167

- Zallmann M, Smith PK, Tang MLK, et al. Debunking the myth of wool allergy: reviewing the evidence for immune and non-immune cutaneous reactions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:906-915. doi:10.2340/00015555-2655

- Yosipovitch G, Nedorost ST, Silverberg JI, et al. Stasis dermatitis: an overview of its clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:275-286. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00753-5

- Johnson H, Novack DE, Adler BL, et al. Can atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis coexist? Cutis. 2022;110:139-142. doi:10.12788/cutis.0599

- Gilissen L, Schollaert I, Huygens S, et al. Iatrogenic allergic contact dermatitis in the (peri)anal and genital area. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84:431-438. doi:10.1111/cod.13764

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Fisher AA. The paraben paradox. Cutis. 1973;12:830-832.

- Kligman AM. The myth of lanolin allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:103-107. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05856.x

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

- Warshaw EM, Nelsen DD, Maibach HI, et al. Positive patch test reactions to lanolin: cross-sectional data from the North American Contact Dermatitis group, 1994 to 2006. Dermatitis. 2009;20:79-88.

- Mortensen T. Allergy to lanolin. Contact Dermatitis. 1979;5:137-139. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1979.tb04824.x

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Amsler E, Assier H, Soria A, et al. What is the optimal duration for a ROAT? the experience of the French Dermatology and Allergology group (DAG). Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:170-175. doi:10.1111/cod.14118

- Msika P, De Belilovsky C, Piccardi N, et al. New emollient with topical corticosteroid-sparing effect in treatment of childhood atopic dermatitis: SCORAD and quality of life improvement. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:606-612. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00783.x

- Lio PA. Alternative therapies in atopic dermatitis care: part 2. Pract Dermatol. July 2011:48-50.

- Karagounis TK, Gittler JK, Rotemberg V, et al. Use of “natural” oils for moisturization: review of olive, coconut, and sunflower seed oil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:9-15. doi:10.1111/pde.13621

Practice Points

- Lanolin is a common ingredient in personal care products (PCPs), cosmetics, topical medicaments, and industrial materials.

- Allergic contact dermatitis to lanolin appears to be most common in patients with stasis dermatitis, chronic leg ulcers, atopic dermatitis, and perianal/genital dermatitis.

- There is no single best lanolin patch test formulation. Patch testing and repeat open application testing to PCPs containing lanolin also may be of benefit.

Is Laundry Detergent a Common Cause of Allergic Contact Dermatitis?

Laundry detergent, a cleaning agent ubiquitous in the modern household, often is suspected as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

We provide a summary of the evidence for the potential allergenicity of laundry detergent, including common allergens present in laundry detergent, the role of machine washing, and the differential diagnosis for laundry detergent–associated ACD.

Allergenic Ingredients in Laundry Detergent

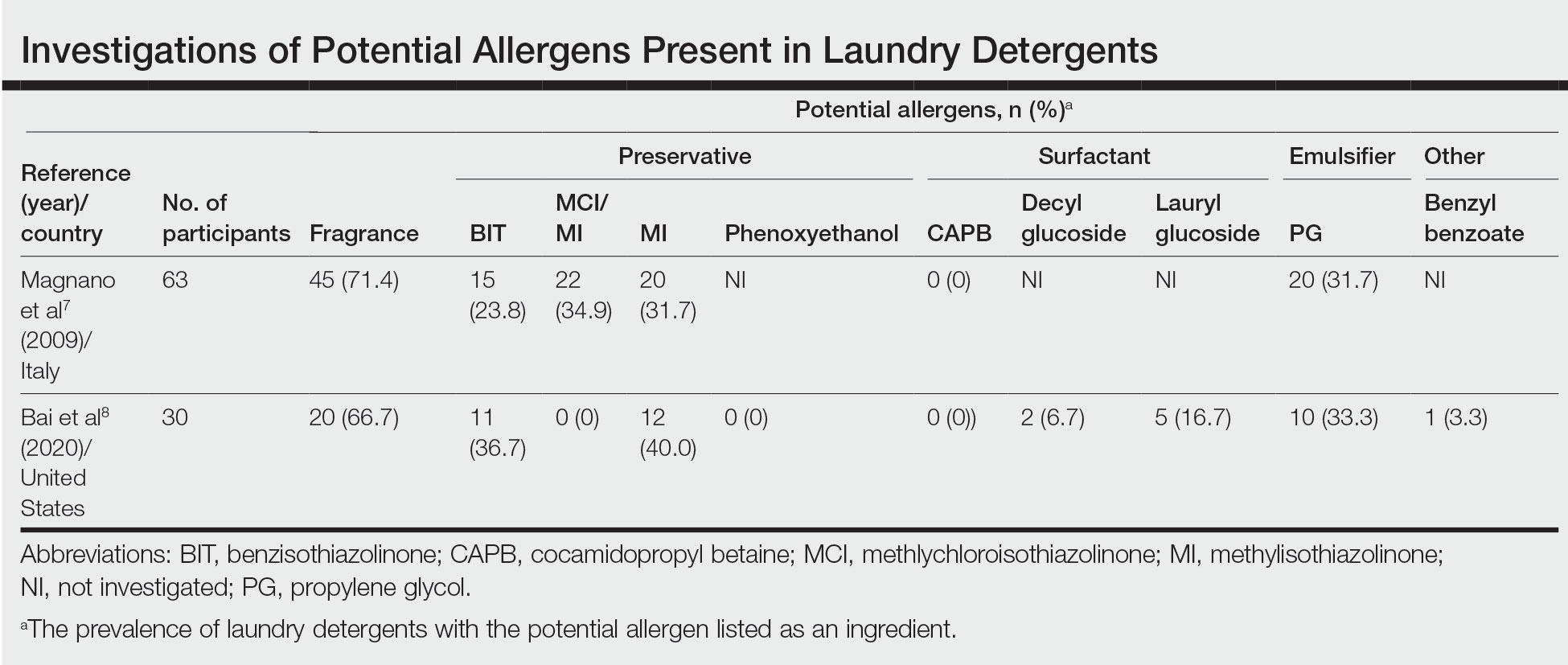

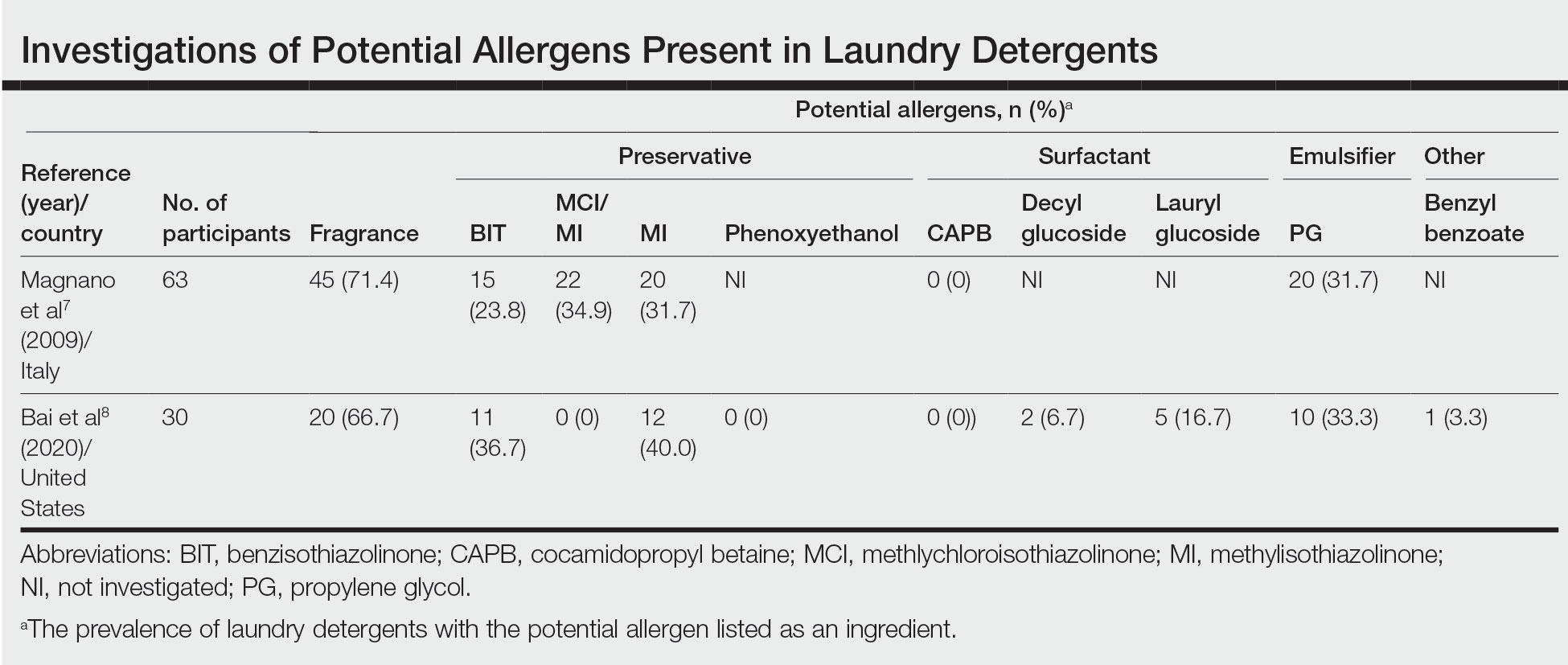

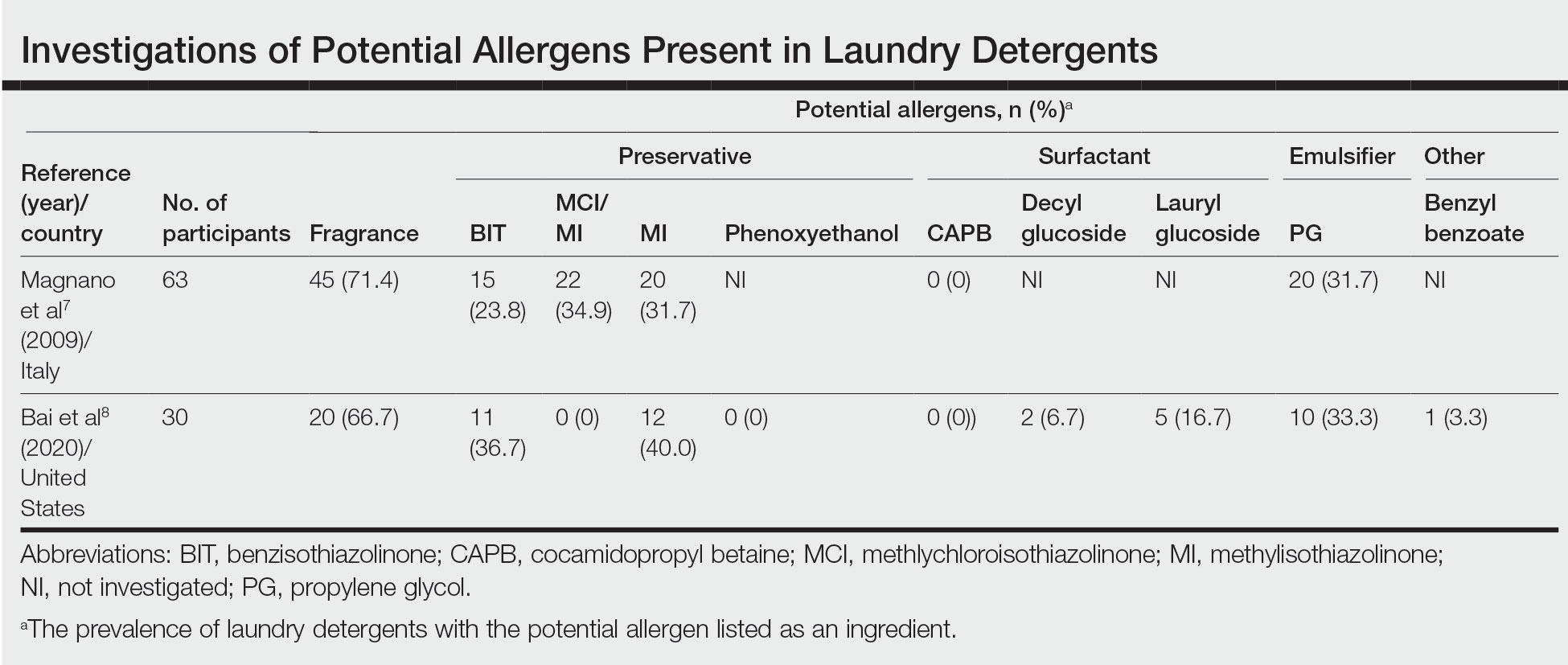

Potential allergens present in laundry detergent include fragrances, preservatives, surfactants, emulsifiers, bleaches, brighteners, enzymes, and dyes.6-8 In an analysis of allergens present in laundry detergents available in the United States, fragrances and preservatives were most common (eTable).7,8 Contact allergy to fragrances occurs in approximately 3.5% of the general population9 and is detected in as many as 9.2% of patients referred for patch testing in North America.10 Preservatives commonly found in laundry detergent include isothiazolinones, such as methylchloroisothiazolinone (MCI)/methylisothiazolinone (MI), MI alone, and benzisothiazolinone (BIT). Methylisothiazolinone has gained attention for causing an ACD epidemic beginning in the early 2000s and peaking in Europe between 2013 and 2014 and decreasing thereafter due to consumer personal care product regulatory changes enacted in the European Union.11 In contrast, rates of MI allergy in North America have continued to increase (reaching as high as 15% of patch tested patients in 2017-2018) due to a lack of similar regulation.10,12 More recently, the prevalence of positive patch tests to BIT has been rising, though it often is difficult to ascertain relevant sources of exposure, and some cases could represent cross-reactions to MCI/MI.10,13

Other allergens that may be present in laundry detergent include surfactants and propylene glycol. Alkyl glucosides such as decyl glucoside and lauryl glucoside are considered gentle surfactants and often are included in products marketed as safe for sensitive skin,14 such as “free and gentle” detergents.8 However, they actually may pose an increased risk for sensitization in patients with atopic dermatitis.14 In addition to being allergenic, surfactants and emulsifiers are known irritants.6,15 Although pathologically distinct, ACD and irritant contact dermatitis can be indistinguishable on clinical presentation.

How Commonly Does Laundry Detergent Cause ACD?

The mere presence of a contact allergen in laundry detergent does not necessarily imply that it is likely to cause ACD. To do so, the chemical in question must exceed the exposure thresholds for primary sensitization (ie, induction of contact allergy) and/or elicitation (ie, development of ACD in sensitized individuals). These depend on a complex interplay of product- and patient-specific factors, among them the concentration of the chemical in the detergent, the method of use, and the amount of detergent residue remaining on clothing after washing.

In the 1990s, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) attempted to determine the prevalence of ACD caused by laundry detergent.1 Among 738 patients patch tested to aqueous dilutions of granular and liquid laundry detergents, only 5 (0.7%) had a possible allergic patch test reaction. It was unclear what the culprit allergens in the detergents may have been; only 1 of the patients also tested positive to fragrance. Two patients underwent further testing to additional detergent dilutions, and the results called into question whether their initial reactions had truly been allergic (positive) or were actually irritant (negative). The investigators concluded that the prevalence of laundry detergent–associated ACD in this large group of patients was at most 0.7%, and possibly lower.1

Importantly, patch testing to laundry detergents should not be undertaken in routine clinical practice. Laundry detergents should never be tested “as is” (ie, undiluted) on the skin; they are inherently irritating and have a high likelihood of producing misleading false-positive reactions. Careful dilutions and testing of control subjects are necessary if patch testing with these products is to be appropriately conducted.

Isothiazolinones in Laundry Detergent

The extremely low prevalence of laundry detergent–associated ACD reported by the NACDG was determined prior to the start of the worldwide MI allergy epidemic, raising the possibility that laundry detergents containing isothiazolinones may be associated with ACD. There is no consensus about the minimum level at which isothiazolinones pose no risk to consumers,16-19 but the US Expert Panel for Cosmetic Ingredient Safety declared that MI is “safe for use in rinse-off cosmetic products at concentrations up to 100 ppm and safe in leave-on cosmetic products when they are formulated to be nonsensitizing.”18,19 Although ingredient lists do not always reveal when isothiazolinones are present, analyses of commercially available laundry detergents have shown MI concentrations ranging from undetectable to 65.7 ppm.20-23

Published reports suggest that MCI/MI in laundry detergent can elicit ACD in sensitized individuals. In one case, a 7-year-old girl with chronic truncal dermatitis (atopic history unspecified) was patch tested, revealing a strongly positive reaction to MCI/MI.24 Her laundry detergent was the only personal product found to contain MI. The dermatitis completely resolved after switching detergents and flared after wearing a jacket that had been washed in the implicated detergent, further supporting the relevance of the positive patch test. The investigators suspected initial sensitization to MI from wet wipes used earlier in childhood.24 In another case involving occupational exposure, a 39-year-old nonatopic factory worker was responsible for directly adding MI to laundry detergent.25 Although he wore disposable work gloves, he developed severe hand dermatitis, eczematous pretibial patches, and generalized pruritus. Patch testing revealed positive reactions to MCI/MI and MI, and he experienced improvement when reassigned to different work duties. It was hypothesized that the leg dermatitis and generalized pruritus may have been related to exposure to small concentrations of MI in work clothes washed with an MI-containing detergent.25 Notably, this patient’s level of exposure was much greater than that encountered by individuals in day-to-day life outside of specialized occupational settings.

Regarding other isothiazolinones, a toxicologic study estimated that BIT in laundry detergent would be unlikely to induce sensitization, even at the maximal acceptable concentration, as recommended by preservative manufacturers, and accounting for undiluted detergent spilling directly onto the skin.26

Does Machine Washing Impact Allergen Concentrations?

Two recent investigations have suggested that machine washing reduces concentrations of isothiazolinones to levels that are likely below clinical relevance. In the first study, 3 fabrics—cotton, polyester, cotton-polyester—were machine washed and line dried.27 A standard detergent was used with MI added at different concentrations: less than 1 ppm, 100 ppm, and 1000 ppm. This process was either performed once or 10 times. Following laundering and line drying, MI was undetectable in all fabrics regardless of MI concentration or number of times washed (detection limit, 0.5 ppm).27 In the second study, 4 fabrics—cotton, wool, polyester, linen—were washed with standard laundry detergent in 1 of 4 ways: handwashing (positive control), standard machine washing, standard machine washing with fabric softener, and standard machine washing with a double rinse.28 After laundering and line drying, concentrations of MI, MCI, and BIT were low or undetectable regardless of fabric type or method of laundering. The highest levels detected were in handwashed garments at a maximum of 0.5 ppm of MI. The study authors postulated that chemical concentrations near these maximum residual levels may pose a risk for eliciting ACD in highly sensitized individuals. Therefore, handwashing can be considered a much higher risk activity for isothiazolinone ACD compared with machine washing.28

It is intriguing that machine washing appears to reduce isothiazolinones to low concentrations that may have limited likelihood of causing ACD. Similar findings have been reported regarding fragrances. A quantitative risk assessment performed on 24 of 26 fragrance allergens regulated by the European Union determined that the amount of fragrance deposited on the skin from laundered garments would be less than the threshold for causing sensitization.29 Although this risk assessment was unable to address the threshold of elicitation, another study conducted in Europe investigated whether fragrance residues present on fabric, such as those deposited from laundry detergent, are present at high enough concentrations to elicit ACD in previously sensitized individuals.30 When 36 individuals were patch tested with increasing concentrations of a fragrance to which they were already sensitized, only 2 (5.6%) had a weakly positive reaction and then only to the highest concentration, which was estimated to be 20-fold higher than the level of skin exposure after normal laundering. No patient reacted at lower concentrations.30

Although machine washing may decrease isothiazolinone and/or fragrance concentrations in laundry detergent to below clinically relevant levels, these findings should not necessarily be extrapolated to all chemicals in laundry detergent. Indeed, a prior study observed that after washing cotton cloths in a detergent solution for 10 minutes, detergent residue was present at concentrations ranging from 139 to 2820 ppm and required a subsequent 20 to 22 washes in water to become undetectable.31 Another study produced a mathematical model of the residual concentration of sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), a surfactant and known irritant, in laundered clothing.32 It was estimated that after machine washing, the residual concentration of SDS on clothes would be too low to cause irritation; however, as the clothes dry (ie, as moisture evaporates but solutes remain), the concentration of SDS on the fabric’s surface would increase to potentially irritating levels. The extensive drying that is possible with electric dryers may further enhance this solute-concentrating effect.

Differential Diagnosis of Laundry Detergent ACD

The propensity for laundry detergent to cause ACD is a question that is nowhere near settled, but the prevalence of allergy likely is far less common than is generally suspected. In our experience, many patients presenting for patch testing have already made the change to “free and clear” detergents without noticeable improvement in their dermatitis, which could possibly relate to the ongoing presence of contact allergens in these “gentle” formulations.7 However, to avoid anchoring bias, more frequent causes of dermatitis should be included in the differential diagnosis. Textile ACD presents beneath clothing with accentuation at areas of closest contact with the skin, classically involving the axillary rim but sparing the vault. The most frequently implicated allergens in textile ACD are disperse dyes and less commonly textile resins.33,34 Between 2017 and 2018, 2.3% of 4882 patients patch tested by the NACDG reacted positively to disperse dye mix.10 There is evidence to suggest that the actual prevalence of disperse dye allergy might be higher due to inadequacy of screening allergens on baseline patch test series.35 Additional diagnoses that should be distinguished from presumed detergent contact dermatitis include atopic dermatitis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Final Interpretation

Although many patients and physicians consider laundry detergent to be a major cause of ACD, there is limited high-quality evidence to support this belief. Contact allergy to laundry detergent is probably much less common than is widely supposed. Although laundry detergents can contain common allergens such as fragrances and preservatives, evidence suggests that they are likely reduced to below clinically relevant levels during routine machine washing; however, we cannot assume that we are in the “free and clear,” as uncertainty remains about the impact of these low concentrationson individuals with strong contact allergy, and large studies of patch testing to modern detergents have yet to be carried out.

- Belsito DV, Fransway AF, Fowler JF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to detergents: a multicenter study to assess prevalence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:200-206. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.119665

- Dallas MJ, Wilson PA, Burns LD, et al. Dermatological and other health problems attributed by consumers to contact with laundry products. Home Econ Res J. 1992;21:34-49. doi:10.1177/1077727X9202100103

- Bailey A. An overview of laundry detergent allergies. Verywell Health. September 16, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.verywellhealth.com/laundry-detergent-allergies-signs-symptoms-and-treatment-5198934

- Fasanella K. How to tell if you laundry detergent is messing with your skin. Allure. June 15, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.allure.com/story/laundry-detergent-allergy-skin-reaction

- Oykhman P, Dookie J, Al-Rammahy et al. Dietary elimination for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Immunol Pract. 2022;10:2657-2666.e8. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2022.06.044

- Kwon S, Holland D, Kern P. Skin safety evaluation of laundry detergent products. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2009;72:1369-1379. doi:10.1080/1528739090321675

- Magnano M, Silvani S, Vincenzi C, et al. Contact allergens and irritants in household washing and cleaning products. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:337-341. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01647.x

- Bai H, Tam I, Yu J. Contact allergens in top-selling textile-care products. Dermatitis. 2020;31:53-58. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000566

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi:10.1111/cod.13119

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000729

- Havmose M, Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, et al. The epidemic of contact allergy to methylisothiazolinone–an analysis of Danish consecutive patients patch tested between 2005 and 2019. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84:254-262. doi:10.1111/cod.13717

- Atwater AR, Petty AJ, Liu B, et al. Contact dermatitis associated with preservatives: retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1994 through 2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:965-976. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.059

- King N, Latheef F, Wilkinson M. Trends in preservative allergy: benzisothiazolinone emerges from the pack. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:637-642. doi:10.1111/cod.13968

- Sasseville D. Alkyl glucosides: 2017 “allergen of the year.” Dermatitis. 2017;28:296. doi:10.1097/DER0000000000000290

- McGowan MA, Scheman A, Jacob SE. Propylene glycol in contact dermatitis: a systematic review. Dermatitis. 2018;29:6-12. doi:10.1097/DER0000000000000307

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Consumers. Opinion on methylisothiazolinone (P94) submission II (sensitisation only). Revised March 27, 2014. Accessed March 21, 2023. http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/consumer_safety/docs/sccs_o_145.pdf

- Cosmetic ingredient hotlist: list of ingredients that are restricted for use in cosmetic products. Government of Canada website. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredient-hotlist-prohibited-restricted-ingredients/hotlist.html#tbl2

- Burnett CL, Boyer I, Bergfeld WF, et al. Amended safety assessment of methylisothiazolinone as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2019;38(1 suppl):70S-84S. doi:10.1177/1091581819838792

- Burnett CL, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, et al. Amended safety assessment of methylisothiazolinone as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2021;40(1 suppl):5S-19S. doi:10.1177/10915818211015795

- Aerts O, Meert H, Goossens A, et al. Methylisothiazolinone in selected consumer products in Belgium: adding fuel to the fire? Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:142-149. doi:10.1111/cod.12449

- Garcia-Hidalgo E, Sottas V, von Goetz N, et al. Occurrence and concentrations of isothiazolinones in detergents and cosmetics in Switzerland. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:96-106. doi:10.1111/cod.12700

- Marrero-Alemán G, Borrego L, Antuña AG, et al. Isothiazolinones in cleaning products: analysis with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry of samples from sensitized patients and markets. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;82:94-100. doi:10.1111/cod.13430

- Alvarez-Rivera G, Dagnac T, Lores M, et al. Determination of isothiazolinone preservatives in cosmetics and household products by matrix solid-phase dispersion followed by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1270:41-50. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2012.10.063

- Cotton CH, Duah CG, Matiz C. Allergic contact dermatitis due to methylisothiazolinone in a young girl’s laundry detergent. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:486-487. doi:10.1111/pde.13122

- Sandvik A, Holm JO. Severe allergic contact dermatitis in a detergent production worker caused by exposure to methylisothiazolinone. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:243-245. doi:10.1111/cod.13182

- Novick RM, Nelson ML, Unice KM, et al. Estimation of safe use concentrations of the preservative 1,2-benziosothiazolin-3-one (BIT) in consumer cleaning products and sunscreens. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;56:60-66. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.02.006

- Hofmann MA, Giménez-Arnau A, Aberer W, et al. MI (2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one) contained in detergents is not detectable in machine washed textiles. Clin Transl Allergy. 2018;8:1. doi:10.1186/s13601-017-0187-2

- Marrero-Alemán G, Borrego L, Atuña AG, et al. Persistence of isothiazolinones in clothes after machine washing. Dermatitis. 2021;32:298-300. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000603

- Corea NV, Basketter DA, Clapp C, et al. Fragrance allergy: assessing the risk from washed fabrics. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:48-53. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00872.x

- Basketter DA, Pons-Guiraud A, van Asten A, et al. Fragrance allergy: assessing the safety of washed fabrics. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:349-354. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01728.x

- Agarwal C, Gupta BN, Mathur AK, et al. Residue analysis of detergent in crockery and clothes. Environmentalist. 1986;4:240-243.

- Broadbridge P, Tilley BS. Diffusion of dermatological irritant in drying laundered cloth. Math Med Biol. 2021;38:474-489. doi:10.1093/imammb/dqab014

- Lisi P, Stingeni L, Cristaudo A, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of textile contact dermatitis: an Italian multicentre study. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;70:344-350. doi:10.1111/cod.12179

- Mobolaji-Lawal M, Nedorost S. The role of textiles in dermatitis: an update. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:17. doi:10.1007/s11882-015-0518-0

- Nijman L, Rustemeyer T, Franken SM, et al. The prevalence and relevance of patch testing with textile dyes [published online December 3, 2022]. Contact Dermatitis. doi:10.1111/cod.14260

Laundry detergent, a cleaning agent ubiquitous in the modern household, often is suspected as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

We provide a summary of the evidence for the potential allergenicity of laundry detergent, including common allergens present in laundry detergent, the role of machine washing, and the differential diagnosis for laundry detergent–associated ACD.

Allergenic Ingredients in Laundry Detergent

Potential allergens present in laundry detergent include fragrances, preservatives, surfactants, emulsifiers, bleaches, brighteners, enzymes, and dyes.6-8 In an analysis of allergens present in laundry detergents available in the United States, fragrances and preservatives were most common (eTable).7,8 Contact allergy to fragrances occurs in approximately 3.5% of the general population9 and is detected in as many as 9.2% of patients referred for patch testing in North America.10 Preservatives commonly found in laundry detergent include isothiazolinones, such as methylchloroisothiazolinone (MCI)/methylisothiazolinone (MI), MI alone, and benzisothiazolinone (BIT). Methylisothiazolinone has gained attention for causing an ACD epidemic beginning in the early 2000s and peaking in Europe between 2013 and 2014 and decreasing thereafter due to consumer personal care product regulatory changes enacted in the European Union.11 In contrast, rates of MI allergy in North America have continued to increase (reaching as high as 15% of patch tested patients in 2017-2018) due to a lack of similar regulation.10,12 More recently, the prevalence of positive patch tests to BIT has been rising, though it often is difficult to ascertain relevant sources of exposure, and some cases could represent cross-reactions to MCI/MI.10,13

Other allergens that may be present in laundry detergent include surfactants and propylene glycol. Alkyl glucosides such as decyl glucoside and lauryl glucoside are considered gentle surfactants and often are included in products marketed as safe for sensitive skin,14 such as “free and gentle” detergents.8 However, they actually may pose an increased risk for sensitization in patients with atopic dermatitis.14 In addition to being allergenic, surfactants and emulsifiers are known irritants.6,15 Although pathologically distinct, ACD and irritant contact dermatitis can be indistinguishable on clinical presentation.

How Commonly Does Laundry Detergent Cause ACD?

The mere presence of a contact allergen in laundry detergent does not necessarily imply that it is likely to cause ACD. To do so, the chemical in question must exceed the exposure thresholds for primary sensitization (ie, induction of contact allergy) and/or elicitation (ie, development of ACD in sensitized individuals). These depend on a complex interplay of product- and patient-specific factors, among them the concentration of the chemical in the detergent, the method of use, and the amount of detergent residue remaining on clothing after washing.

In the 1990s, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) attempted to determine the prevalence of ACD caused by laundry detergent.1 Among 738 patients patch tested to aqueous dilutions of granular and liquid laundry detergents, only 5 (0.7%) had a possible allergic patch test reaction. It was unclear what the culprit allergens in the detergents may have been; only 1 of the patients also tested positive to fragrance. Two patients underwent further testing to additional detergent dilutions, and the results called into question whether their initial reactions had truly been allergic (positive) or were actually irritant (negative). The investigators concluded that the prevalence of laundry detergent–associated ACD in this large group of patients was at most 0.7%, and possibly lower.1

Importantly, patch testing to laundry detergents should not be undertaken in routine clinical practice. Laundry detergents should never be tested “as is” (ie, undiluted) on the skin; they are inherently irritating and have a high likelihood of producing misleading false-positive reactions. Careful dilutions and testing of control subjects are necessary if patch testing with these products is to be appropriately conducted.

Isothiazolinones in Laundry Detergent

The extremely low prevalence of laundry detergent–associated ACD reported by the NACDG was determined prior to the start of the worldwide MI allergy epidemic, raising the possibility that laundry detergents containing isothiazolinones may be associated with ACD. There is no consensus about the minimum level at which isothiazolinones pose no risk to consumers,16-19 but the US Expert Panel for Cosmetic Ingredient Safety declared that MI is “safe for use in rinse-off cosmetic products at concentrations up to 100 ppm and safe in leave-on cosmetic products when they are formulated to be nonsensitizing.”18,19 Although ingredient lists do not always reveal when isothiazolinones are present, analyses of commercially available laundry detergents have shown MI concentrations ranging from undetectable to 65.7 ppm.20-23

Published reports suggest that MCI/MI in laundry detergent can elicit ACD in sensitized individuals. In one case, a 7-year-old girl with chronic truncal dermatitis (atopic history unspecified) was patch tested, revealing a strongly positive reaction to MCI/MI.24 Her laundry detergent was the only personal product found to contain MI. The dermatitis completely resolved after switching detergents and flared after wearing a jacket that had been washed in the implicated detergent, further supporting the relevance of the positive patch test. The investigators suspected initial sensitization to MI from wet wipes used earlier in childhood.24 In another case involving occupational exposure, a 39-year-old nonatopic factory worker was responsible for directly adding MI to laundry detergent.25 Although he wore disposable work gloves, he developed severe hand dermatitis, eczematous pretibial patches, and generalized pruritus. Patch testing revealed positive reactions to MCI/MI and MI, and he experienced improvement when reassigned to different work duties. It was hypothesized that the leg dermatitis and generalized pruritus may have been related to exposure to small concentrations of MI in work clothes washed with an MI-containing detergent.25 Notably, this patient’s level of exposure was much greater than that encountered by individuals in day-to-day life outside of specialized occupational settings.

Regarding other isothiazolinones, a toxicologic study estimated that BIT in laundry detergent would be unlikely to induce sensitization, even at the maximal acceptable concentration, as recommended by preservative manufacturers, and accounting for undiluted detergent spilling directly onto the skin.26

Does Machine Washing Impact Allergen Concentrations?

Two recent investigations have suggested that machine washing reduces concentrations of isothiazolinones to levels that are likely below clinical relevance. In the first study, 3 fabrics—cotton, polyester, cotton-polyester—were machine washed and line dried.27 A standard detergent was used with MI added at different concentrations: less than 1 ppm, 100 ppm, and 1000 ppm. This process was either performed once or 10 times. Following laundering and line drying, MI was undetectable in all fabrics regardless of MI concentration or number of times washed (detection limit, 0.5 ppm).27 In the second study, 4 fabrics—cotton, wool, polyester, linen—were washed with standard laundry detergent in 1 of 4 ways: handwashing (positive control), standard machine washing, standard machine washing with fabric softener, and standard machine washing with a double rinse.28 After laundering and line drying, concentrations of MI, MCI, and BIT were low or undetectable regardless of fabric type or method of laundering. The highest levels detected were in handwashed garments at a maximum of 0.5 ppm of MI. The study authors postulated that chemical concentrations near these maximum residual levels may pose a risk for eliciting ACD in highly sensitized individuals. Therefore, handwashing can be considered a much higher risk activity for isothiazolinone ACD compared with machine washing.28

It is intriguing that machine washing appears to reduce isothiazolinones to low concentrations that may have limited likelihood of causing ACD. Similar findings have been reported regarding fragrances. A quantitative risk assessment performed on 24 of 26 fragrance allergens regulated by the European Union determined that the amount of fragrance deposited on the skin from laundered garments would be less than the threshold for causing sensitization.29 Although this risk assessment was unable to address the threshold of elicitation, another study conducted in Europe investigated whether fragrance residues present on fabric, such as those deposited from laundry detergent, are present at high enough concentrations to elicit ACD in previously sensitized individuals.30 When 36 individuals were patch tested with increasing concentrations of a fragrance to which they were already sensitized, only 2 (5.6%) had a weakly positive reaction and then only to the highest concentration, which was estimated to be 20-fold higher than the level of skin exposure after normal laundering. No patient reacted at lower concentrations.30

Although machine washing may decrease isothiazolinone and/or fragrance concentrations in laundry detergent to below clinically relevant levels, these findings should not necessarily be extrapolated to all chemicals in laundry detergent. Indeed, a prior study observed that after washing cotton cloths in a detergent solution for 10 minutes, detergent residue was present at concentrations ranging from 139 to 2820 ppm and required a subsequent 20 to 22 washes in water to become undetectable.31 Another study produced a mathematical model of the residual concentration of sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), a surfactant and known irritant, in laundered clothing.32 It was estimated that after machine washing, the residual concentration of SDS on clothes would be too low to cause irritation; however, as the clothes dry (ie, as moisture evaporates but solutes remain), the concentration of SDS on the fabric’s surface would increase to potentially irritating levels. The extensive drying that is possible with electric dryers may further enhance this solute-concentrating effect.

Differential Diagnosis of Laundry Detergent ACD

The propensity for laundry detergent to cause ACD is a question that is nowhere near settled, but the prevalence of allergy likely is far less common than is generally suspected. In our experience, many patients presenting for patch testing have already made the change to “free and clear” detergents without noticeable improvement in their dermatitis, which could possibly relate to the ongoing presence of contact allergens in these “gentle” formulations.7 However, to avoid anchoring bias, more frequent causes of dermatitis should be included in the differential diagnosis. Textile ACD presents beneath clothing with accentuation at areas of closest contact with the skin, classically involving the axillary rim but sparing the vault. The most frequently implicated allergens in textile ACD are disperse dyes and less commonly textile resins.33,34 Between 2017 and 2018, 2.3% of 4882 patients patch tested by the NACDG reacted positively to disperse dye mix.10 There is evidence to suggest that the actual prevalence of disperse dye allergy might be higher due to inadequacy of screening allergens on baseline patch test series.35 Additional diagnoses that should be distinguished from presumed detergent contact dermatitis include atopic dermatitis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Final Interpretation

Although many patients and physicians consider laundry detergent to be a major cause of ACD, there is limited high-quality evidence to support this belief. Contact allergy to laundry detergent is probably much less common than is widely supposed. Although laundry detergents can contain common allergens such as fragrances and preservatives, evidence suggests that they are likely reduced to below clinically relevant levels during routine machine washing; however, we cannot assume that we are in the “free and clear,” as uncertainty remains about the impact of these low concentrationson individuals with strong contact allergy, and large studies of patch testing to modern detergents have yet to be carried out.

Laundry detergent, a cleaning agent ubiquitous in the modern household, often is suspected as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

We provide a summary of the evidence for the potential allergenicity of laundry detergent, including common allergens present in laundry detergent, the role of machine washing, and the differential diagnosis for laundry detergent–associated ACD.

Allergenic Ingredients in Laundry Detergent

Potential allergens present in laundry detergent include fragrances, preservatives, surfactants, emulsifiers, bleaches, brighteners, enzymes, and dyes.6-8 In an analysis of allergens present in laundry detergents available in the United States, fragrances and preservatives were most common (eTable).7,8 Contact allergy to fragrances occurs in approximately 3.5% of the general population9 and is detected in as many as 9.2% of patients referred for patch testing in North America.10 Preservatives commonly found in laundry detergent include isothiazolinones, such as methylchloroisothiazolinone (MCI)/methylisothiazolinone (MI), MI alone, and benzisothiazolinone (BIT). Methylisothiazolinone has gained attention for causing an ACD epidemic beginning in the early 2000s and peaking in Europe between 2013 and 2014 and decreasing thereafter due to consumer personal care product regulatory changes enacted in the European Union.11 In contrast, rates of MI allergy in North America have continued to increase (reaching as high as 15% of patch tested patients in 2017-2018) due to a lack of similar regulation.10,12 More recently, the prevalence of positive patch tests to BIT has been rising, though it often is difficult to ascertain relevant sources of exposure, and some cases could represent cross-reactions to MCI/MI.10,13

Other allergens that may be present in laundry detergent include surfactants and propylene glycol. Alkyl glucosides such as decyl glucoside and lauryl glucoside are considered gentle surfactants and often are included in products marketed as safe for sensitive skin,14 such as “free and gentle” detergents.8 However, they actually may pose an increased risk for sensitization in patients with atopic dermatitis.14 In addition to being allergenic, surfactants and emulsifiers are known irritants.6,15 Although pathologically distinct, ACD and irritant contact dermatitis can be indistinguishable on clinical presentation.

How Commonly Does Laundry Detergent Cause ACD?

The mere presence of a contact allergen in laundry detergent does not necessarily imply that it is likely to cause ACD. To do so, the chemical in question must exceed the exposure thresholds for primary sensitization (ie, induction of contact allergy) and/or elicitation (ie, development of ACD in sensitized individuals). These depend on a complex interplay of product- and patient-specific factors, among them the concentration of the chemical in the detergent, the method of use, and the amount of detergent residue remaining on clothing after washing.

In the 1990s, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) attempted to determine the prevalence of ACD caused by laundry detergent.1 Among 738 patients patch tested to aqueous dilutions of granular and liquid laundry detergents, only 5 (0.7%) had a possible allergic patch test reaction. It was unclear what the culprit allergens in the detergents may have been; only 1 of the patients also tested positive to fragrance. Two patients underwent further testing to additional detergent dilutions, and the results called into question whether their initial reactions had truly been allergic (positive) or were actually irritant (negative). The investigators concluded that the prevalence of laundry detergent–associated ACD in this large group of patients was at most 0.7%, and possibly lower.1

Importantly, patch testing to laundry detergents should not be undertaken in routine clinical practice. Laundry detergents should never be tested “as is” (ie, undiluted) on the skin; they are inherently irritating and have a high likelihood of producing misleading false-positive reactions. Careful dilutions and testing of control subjects are necessary if patch testing with these products is to be appropriately conducted.

Isothiazolinones in Laundry Detergent