User login

Rotator cuff injuries can be a source of debilitating pain and dysfunction in athletes at all levels, occasionally precluding return to competitive sport. Overhead athletes place extraordinary physiologic demands on the shoulder, as humeral angular velocities of 7000° to 8000° per second and rotational torques higher than 70 Nm have been measured during the baseball pitch.1 Repetitive supraphysiologic loading of the rotator cuff throughout the coordinated phases of throwing can result in a characteristic spectrum of shoulder pathology in overhead throwers. Several studies have demonstrated partial-thickness articular-sided rotator cuff tears (RCTs) in the area of the posterior supraspinatus and anterior infraspinatus tendons.2-4 Although the precise mechanism remains unclear, plausible explanations for the pathogenesis of these injuries include eccentric tensile and shear forces that lead to tendon failure with repetitive throwing, as well as internal impingement (mechanical impingement of the aforementioned tendons against the posterosuperior glenoid at 90° of shoulder abduction and maximum external rotation).5,6

Whereas partial-thickness articular-sided RCTs have been described in overhead athletes with rotator cuff pathology, full-thickness tears are encountered less often.7,8 Accordingly, there is a paucity of literature on clinical outcomes in professional baseball players with these injuries. To our knowledge, only 2 studies have investigated functional outcomes of open surgical repair of full-thickness tears in this population, and the outcomes have been uniformly poor.8,9

An anatomical description of rotator cuff anatomy has demonstrated a consistent pattern of supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon insertion relative to the articular surface, biceps groove, and the bare area of the humerus.10 Using gross and microscopic analyses, the authors noted that the supraspinatus tendon inserted immediately adjacent to the articular margin, and the infraspinatus and teres minor tapered laterally away from the margin to form the bare area. Detailed knowledge of the insertional anatomy of the rotator cuff is important, as surgical repair should recreate the broad footprint to restore normal biomechanics and increase the surface area available for healing.11,12 Medial advancement of the rotator cuff insertion during surgical repair can have deleterious biomechanical effects on glenohumeral motion.11

Given the unfavorable results found after routine open repair of full-thickness tears, we altered our approach to these injuries and adopted an arthroscopic technique in which the tendon is repaired immediately lateral to the anatomical footprint. Research studies have demonstrated that chronic stress from repetitive throwing can lead to attenuation of soft-tissue restraints, and we think preservation of these adaptive changes after surgical repair may be important for these athletes to maintain extraordinary glenohumeral rotation and achieve high throwing velocities.13 We conducted a study to describe the lateralized repair technique for full-thickness RCTs and to report functional outcomes in Major League Baseball (MLB) pitchers treated with this procedure at minimum 2-year follow-up. We hypothesized that use of this novel technique would result in a higher rate of return to preinjury level of play in comparison with open rotator cuff repair in comparable cohorts, as reported in other studies.8,9

Materials and Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we performed a retrospective chart review of MLB players treated by Dr. Altchek. We identified all professional baseball players who received a diagnosis of full-thickness RCT after preoperative magnetic resonance imaging with subsequent confirmation during surgery. Any patient who underwent arthroscopic repair using the lateralized footprint technique was included in the study. Demographic and preoperative injury information was collected from the chart, and final follow-up data were collected at the last available clinic visit. From available team records, we also obtained return-to-play data and objective pitching statistics: seasons played, games played, innings pitched, strikeouts per 9 innings, walks per 9 innings, and earned run average.

Surgical Technique

We routinely perform arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs with the patient under regional anesthesia in the beach-chair position. The operative extremity is placed in a Spider Limb Positioner (Smith & Nephew) to facilitate easy manipulation of the arm throughout the procedure. A standard posterior portal is established, and then an anterior portal is placed in the superolateral aspect of the rotator interval directly anterior to the leading edge of the supraspinatus tendon. A lateral portal created 2 to 3 cm distal to the anterolateral margin of the acromion may be used as an additional working portal. A thorough diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to evaluate the glenohumeral joint for any concomitant intra-articular pathology. Particular attention is directed to inspection of the superior labrum, biceps tendon, and capsuloligamentous structures, as injuries to these structures are often associated with rotator cuff pathology in overhead athletes.

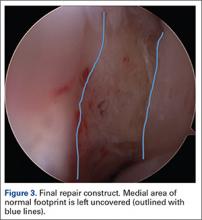

Once presence of an RCT is confirmed, a thorough subacromial bursectomy is performed to help with visualization and inspection of the injury. The tissue is provisionally grasped and mobilized to measure the amount of available tendon excursion. In this unique population, the vast majority of injuries are diagnosed in an expeditious manner, thereby precluding the presence of significant retraction, poor tissue quality, and inadequate mobilization of the tendons. The greater tuberosity is identified, and the area immediately adjacent to the articular margin is abraded with a mechanical shaver to enhance healing potential. For supraspinatus tears, an anchor is placed immediately lateral to the articular margin in the region of the anterior attachment of the rotator cable (Figure 1). The posterior anchor is placed about 10 to 15 mm lateral to the articular margin to reattach the infraspinatus tendon (Figure 2). When the medial row sutures are tied down, anatomical placement of these anchors effectively re-creates the bare area described by Curtis and colleagues10 (Figure 3). In most cases, the medial row sutures are left intact and fixed laterally with a knotless anchor to provide a transosseous equivalent (double-row) repair.

Results

We identified 6 MLB pitchers who underwent arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using the aforementioned technique over an 8-year period. Each patient presented with complaints of debilitating shoulder pain and decreased pitching performance, including loss of throwing accuracy and velocity. There were 4 right-hand–dominant pitchers and 2 left-hand–dominant pitchers; rotator cuff pathology was observed in the dominant pitching arm in each case. Three players were classified as starting pitchers; the other 3 pitched in a relief role. Mean age of all pitchers at time of surgery was 29.8 years (range, 25-37 years). According to records, 2 patients (33%) underwent previous rotator cuff débridement for partial-thickness RCTs before surgical intervention at our institution. Operative information on the depth of the partial-thickness tears observed during the previous procedures was not available for review. At time of rotator cuff repair, 3 patients (50%) underwent concomitant procedures, including superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesion repair (1 patient) and posterior labrum débridement (2 patients). A double-row fixation construct was achieved in each case. Review of operative records revealed a mean tear size of 2.1 cm (range, 1.5-3.0 cm) measured anterior to posterior, and all tears involved the supraspinatus and/or infraspinatus tendons. Postoperative rehabilitation included immobilization in a sling for 4 weeks. Hand, wrist, and elbow range-of-motion (ROM) exercises were started immediately to help reduce inflammation. Passive ROM exercises in the plane of the scapula were begun 4 weeks after surgery. Isometric scapular stabilization exercises were also incorporated at that time. Active-assisted ROM exercises were started at about 6 weeks, and isometric strengthening exercises were started at week 8 with progression to eccentric strengthening and weight training at about 3 months. Most pitchers were allowed to begin an interval throwing program at 24 weeks. There were no significant differences in the therapy programs for pitchers who underwent concomitant labral procedures, but the patient who underwent SLAP repair was limited to 30° of external rotation and 90° of forward flexion, with avoidance of active biceps contractions, for the first 6 weeks of rehabilitation.

By mean follow-up of 66.7 months (range, 23.2-94.6 months), 5 pitchers (83%) returned to their preinjury level of competition for at least 1 full season. One player pitched at Minor League Class AA level for about 1 season but was forced to retire because of persistent symptoms related to the shoulder. This pitcher underwent simultaneous rotator cuff and SLAP lesion repair. Of the 5 pitchers who resumed MLB play, none returned to their preoperative pitching productivity; mean number of innings pitched decreased from 1806.5 to 183.7. Three (60%) of these 5 pitchers experienced a slight reduction in performance as measured by earned run average. Interestingly, both players over age 30 years at time of surgery, versus 3 of the 4 pitchers under age 30 years, returned to their preoperative level of competition for at least 1 season. The Table summarizes MLB player data and objective pitching statistics. There were no perioperative complications related to this arthroscopic technique, and there were no glenohumeral ROM deficits at final follow-up.

Discussion

Although the incidence of full-thickness RCTs in professional baseball players is presumably low, available studies suggest that it is a debilitating injury with a poor prognosis for return to high-level athletics. Mazoué and Andrews9 reviewed the outcomes of 16 professional baseball players (12 pitchers, 4 position players) who underwent mini-open repair of full-thickness RCTs that involved more than 90% of the rotator cuff. Fifteen patients underwent mini-open rotator cuff repair using suture anchors in the anatomical footprint along with bone tunnels established near the lateral margin of the greater tuberosity to create a 2-level anatomical repair. One patient was treated with a mini-open repair using suture anchors in the greater tuberosity with a side-side repair of a longitudinal split within the rotator cuff. In the evaluation of outcomes by player position, only 1 pitcher (8%) returned to a competitive level of pitching at a mean follow-up of 67 months. On review of 2 position players with a full-thickness RCT in the dominant shoulder, only 1 (50%) returned to Major League play at a mean follow-up of 62.5 months. The remaining 2 position players underwent surgical repair of the nondominant shoulder, and, not surprisingly, both returned to their previous level of athletic activity without any difficulty. These results should be examined carefully, as the associated pathology in this high-demand cohort should not be discounted. Eleven (almost 92%) of the 12 pitchers had undergone at least 1 previous procedure on the shoulder. Furthermore, at time of full-thickness rotator cuff repair, 9 (75%) of the 12 pitchers were treated for concomitant intra-articular pathology, including SLAP tears, capsular attenuation, and/or labral fraying. In our study, 50% of pitchers underwent an associated labral procedure. Although labral débridement did not have a significant effect on return to play, the 1 pitcher who underwent SLAP repair was not able to return to preinjury level of play.

Tibone and colleagues8 reviewed postoperative outcomes in 45 athletes with rotator cuff pathology. Within their series, 5 professional baseball pitchers with full-thickness tears were treated with open subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair. Two baseball pitchers with RCTs larger than 2 cm underwent open transosseous footprint repair in which the cuff was reinserted using bone tunnels created within the greater tuberosity. At long-term follow-up, only 2 (40%) of the 5 pitchers returned to competitive pitching. Interestingly, both pitchers who underwent transosseous footprint fixation were unable to return to professional baseball.

Overhead athletes require a delicate balance of shoulder mobility and stability to meet the high functional demands of their sports. Significant debate continues as to whether innate alterations in glenohumeral mobility preselect individuals for overhead sports, or if these changes are acquired through adaptations in supporting soft-tissue and osseous structures. Sethi and colleagues14 used an instrumented manual laxity examination to compare anterior-posterior laxity in asymptomatic professional and Division I college baseball players. The authors noted asymmetric anterior-posterior translation (>3 mm) between the throwing shoulder and the nondominant shoulder in 12 (60%) of 20 professional pitchers and 10 (59%) of 17 college pitchers. Although the authors did not correlate translational differences with corresponding shoulder pathology, the observed asymmetry supported the idea that these athletes may experience adaptive glenohumeral changes with repetitive throwing. The association between adaptive changes and shoulder biomechanics has been studied. Burkhart and Lo15 used a cadaveric model to describe the cam effect of the proximal humerus and the biomechanical consequences of a relative reduction in this effect after pathologic changes within the glenohumeral joint (constriction of posteroinferior capsule). They noted that a posterosuperior shift in the glenohumeral contact point in the throwing position can result in anterior capsular redundancy that may contribute to microinstability of the shoulder. This relative laxity increases external rotation, resulting in increased torsional and shear forces at the rotator cuff insertion.16 Ultimately, these abnormal forces may predispose overhead athletes to rotator cuff injury.

Given the available literature, it is clear that full-thickness RCTs are potentially career-ending injuries for professional baseball players. The question arises as to why the results are so poor. Ultimately, the high incidence of concomitant intra-articular pathology associated with full-thickness RCTs underscores the severity of soft-tissue damage sustained with repetitive overhead throwing. Mazoué and Andrews9 proposed the presence of associated labral and capsular pathology as a potential explanation for poor outcomes of surgical repair. Given the myriad of additional pathology observed in each patient, it is difficult to ascertain the precise impact of these injuries on postoperative outcome. However, early diagnosis and aggressive surgical intervention are clearly necessary to prevent accumulative injury. Regarding surgical intervention, both Tibone and colleagues8 and Mazoué and Andrews9 reported use of an open surgical repair technique in which the tendon was repaired to the anatomical footprint. Certainly, the benefits of an all-arthroscopic technique include optimal visualization of the RCT, less perioperative morbidity, and minimal soft-tissue injury. With our arthroscopic technique, the rotator cuff was fixed immediately lateral to the anatomical footprint, thereby leaving the medial aspect of the footprint uncovered. Functionally, the goal of this procedure is to restore the integrity of the rotator cuff without compromising glenohumeral mobility acquired through soft-tissue adaptation. Investigation of the insertional anatomy of the rotator cuff has demonstrated that the supraspinatus tendon inserts about 0.9 mm from the edge of the articular surface, and the infraspinatus insertional footprint tapers away from the articular surface to form the bare area as it extends inferiorly on the greater tuberosity.10 We think preexisting adaptations in glenohumeral anatomy are important for peak performance in this unique population, and even small alterations in the repair location can have deleterious effects on throwing mechanics. Lateralized repair of the cuff precludes potential medialization of the cuff insertion and may facilitate preservation of soft-tissue adaptations that these athletes rely on to achieve extraordinary glenohumeral motion.

Interestingly, with this technique we noted a higher rate of return to MLB play in pitchers over age 30 years. Although several individual factors (eg, player talent level, work ethics, compliance with rehabilitation) may play a role in this finding, it is possible that older, more mature patients may be more willing to assume diminished roles to continue to play. Jones and colleagues17 recently reported similar findings in older MLB pitchers after revision ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction.

This study had several limitations. First, the patient cohort was small (a result of the nature and relatively infrequent incidence of the clinical problem). Second, clinical information was collected retrospectively, which limited our ability to determine precise differences between preoperative and postoperative glenohumeral ROM with this technique. Third, the cohort included patients who demonstrated additional intra-articular (labral) pathology. Although associated pathology is common in this high-demand athletic population, it is clear that advanced pathology (eg, SLAP tears) may affect clinical outcomes, as in our study. Despite these limitations, our study is the largest review of professional baseball players treated for full-thickness rotator cuff injuries with an arthroscopic technique. Overall, the results of this study are promising and call for further clinical and biomechanical evaluation.

Conclusion

Surgical management of rotator cuff injuries in professional baseball players remains an extremely difficult problem. Current studies of full-thickness RCTs highlight these athletes’ poor functional outcomes. These unfavorable results prompted us to alter our surgical technique. Initial outcomes have been encouraging, and extended follow-up in this cohort of patients will provide a more definitive assessment of the success of this technique.

1. Dillman CJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of pitching with emphasis upon shoulder kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(2):402-408.

2. Andrews JR, Broussard TS, Carson WG. Arthroscopy of the shoulder in the management of partial tears of the rotator cuff: a preliminary report. Arthroscopy. 1985;1(2):117-122.

3. Paley KJ, Jobe FW, Pink MM, Kvitne RS, ElAttrache NS. Arthroscopic findings in the overhead throwing athlete: evidence for posterior internal impingement of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(1):35-40.

4. Nakagawa S, Yoneda M, Hayashida K, Wakitani S, Okamura K. Greater tuberosity notch: an important indicator of articular-side partial rotator cuff tears in the shoulders of throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(6):762-770.

5. Walch G, Boileau P, Noel E, Donell ST. Impingement of the deep surface of the supraspinatus tendon on the posterosuperior glenoid rim: an arthroscopic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1(5):238-245.

6. Halbrecht JL, Tirman P, Atkin D. Internal impingement of the shoulder: comparison of findings between the throwing and nonthrowing shoulders of college baseball players. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(3):253-258.

7. Reynolds SB, Dugas JR, Cain EL, McMichael CS, Andrews JR. Debridement of small partial-thickness rotator cuff tears in elite overhead throwers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):614-621.

8. Tibone JE, Elrod B, Jobe FW, et al. Surgical treatment of tears of the rotator cuff in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(6):887-891.

9. Mazoué C, Andrews JR. Repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34():182-189.

10. Curtis AS, Burbank KM, Tierney JJ, Scheller AD, Curran AR. The insertional footprint of the rotator cuff: an anatomic study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(6):603-609.

11. Liu J, Hughes RE, O’Driscoll SW, An K. Biomechanical effect of medial advancement of the supraspinatus tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(6):853-859.

12. Lo IK, Burkhart SS. Double row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: re-establishing the footprint of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(9):1035-1042.

13. Borsa PA, Laudner KG, Sauers EL. Mobility and stability adaptations in the shoulder of the overhead athlete: a theoretical and evidence-based perspective. Sports Med. 2008;38(1):17-36.

14. Sethi PM, Tibone JE, Lee TQ. Quantitative assessment of glenohumeral translation in baseball players: a comparison of pitchers versus nonpitching athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(7):1711-1715.

15. Burkhart SS, Lo IK. The cam effect of the proximal humerus: its role in the production of relative capsular redundancy of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(3):241-246.

16. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology. Part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):404-420.

17. Jones KJ, Conte S, Patterson N, ElAttrache NS, Dines JS. Functional outcomes following revision ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in Major League Baseball pitchers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(5):642-646.

Rotator cuff injuries can be a source of debilitating pain and dysfunction in athletes at all levels, occasionally precluding return to competitive sport. Overhead athletes place extraordinary physiologic demands on the shoulder, as humeral angular velocities of 7000° to 8000° per second and rotational torques higher than 70 Nm have been measured during the baseball pitch.1 Repetitive supraphysiologic loading of the rotator cuff throughout the coordinated phases of throwing can result in a characteristic spectrum of shoulder pathology in overhead throwers. Several studies have demonstrated partial-thickness articular-sided rotator cuff tears (RCTs) in the area of the posterior supraspinatus and anterior infraspinatus tendons.2-4 Although the precise mechanism remains unclear, plausible explanations for the pathogenesis of these injuries include eccentric tensile and shear forces that lead to tendon failure with repetitive throwing, as well as internal impingement (mechanical impingement of the aforementioned tendons against the posterosuperior glenoid at 90° of shoulder abduction and maximum external rotation).5,6

Whereas partial-thickness articular-sided RCTs have been described in overhead athletes with rotator cuff pathology, full-thickness tears are encountered less often.7,8 Accordingly, there is a paucity of literature on clinical outcomes in professional baseball players with these injuries. To our knowledge, only 2 studies have investigated functional outcomes of open surgical repair of full-thickness tears in this population, and the outcomes have been uniformly poor.8,9

An anatomical description of rotator cuff anatomy has demonstrated a consistent pattern of supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon insertion relative to the articular surface, biceps groove, and the bare area of the humerus.10 Using gross and microscopic analyses, the authors noted that the supraspinatus tendon inserted immediately adjacent to the articular margin, and the infraspinatus and teres minor tapered laterally away from the margin to form the bare area. Detailed knowledge of the insertional anatomy of the rotator cuff is important, as surgical repair should recreate the broad footprint to restore normal biomechanics and increase the surface area available for healing.11,12 Medial advancement of the rotator cuff insertion during surgical repair can have deleterious biomechanical effects on glenohumeral motion.11

Given the unfavorable results found after routine open repair of full-thickness tears, we altered our approach to these injuries and adopted an arthroscopic technique in which the tendon is repaired immediately lateral to the anatomical footprint. Research studies have demonstrated that chronic stress from repetitive throwing can lead to attenuation of soft-tissue restraints, and we think preservation of these adaptive changes after surgical repair may be important for these athletes to maintain extraordinary glenohumeral rotation and achieve high throwing velocities.13 We conducted a study to describe the lateralized repair technique for full-thickness RCTs and to report functional outcomes in Major League Baseball (MLB) pitchers treated with this procedure at minimum 2-year follow-up. We hypothesized that use of this novel technique would result in a higher rate of return to preinjury level of play in comparison with open rotator cuff repair in comparable cohorts, as reported in other studies.8,9

Materials and Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we performed a retrospective chart review of MLB players treated by Dr. Altchek. We identified all professional baseball players who received a diagnosis of full-thickness RCT after preoperative magnetic resonance imaging with subsequent confirmation during surgery. Any patient who underwent arthroscopic repair using the lateralized footprint technique was included in the study. Demographic and preoperative injury information was collected from the chart, and final follow-up data were collected at the last available clinic visit. From available team records, we also obtained return-to-play data and objective pitching statistics: seasons played, games played, innings pitched, strikeouts per 9 innings, walks per 9 innings, and earned run average.

Surgical Technique

We routinely perform arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs with the patient under regional anesthesia in the beach-chair position. The operative extremity is placed in a Spider Limb Positioner (Smith & Nephew) to facilitate easy manipulation of the arm throughout the procedure. A standard posterior portal is established, and then an anterior portal is placed in the superolateral aspect of the rotator interval directly anterior to the leading edge of the supraspinatus tendon. A lateral portal created 2 to 3 cm distal to the anterolateral margin of the acromion may be used as an additional working portal. A thorough diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to evaluate the glenohumeral joint for any concomitant intra-articular pathology. Particular attention is directed to inspection of the superior labrum, biceps tendon, and capsuloligamentous structures, as injuries to these structures are often associated with rotator cuff pathology in overhead athletes.

Once presence of an RCT is confirmed, a thorough subacromial bursectomy is performed to help with visualization and inspection of the injury. The tissue is provisionally grasped and mobilized to measure the amount of available tendon excursion. In this unique population, the vast majority of injuries are diagnosed in an expeditious manner, thereby precluding the presence of significant retraction, poor tissue quality, and inadequate mobilization of the tendons. The greater tuberosity is identified, and the area immediately adjacent to the articular margin is abraded with a mechanical shaver to enhance healing potential. For supraspinatus tears, an anchor is placed immediately lateral to the articular margin in the region of the anterior attachment of the rotator cable (Figure 1). The posterior anchor is placed about 10 to 15 mm lateral to the articular margin to reattach the infraspinatus tendon (Figure 2). When the medial row sutures are tied down, anatomical placement of these anchors effectively re-creates the bare area described by Curtis and colleagues10 (Figure 3). In most cases, the medial row sutures are left intact and fixed laterally with a knotless anchor to provide a transosseous equivalent (double-row) repair.

Results

We identified 6 MLB pitchers who underwent arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using the aforementioned technique over an 8-year period. Each patient presented with complaints of debilitating shoulder pain and decreased pitching performance, including loss of throwing accuracy and velocity. There were 4 right-hand–dominant pitchers and 2 left-hand–dominant pitchers; rotator cuff pathology was observed in the dominant pitching arm in each case. Three players were classified as starting pitchers; the other 3 pitched in a relief role. Mean age of all pitchers at time of surgery was 29.8 years (range, 25-37 years). According to records, 2 patients (33%) underwent previous rotator cuff débridement for partial-thickness RCTs before surgical intervention at our institution. Operative information on the depth of the partial-thickness tears observed during the previous procedures was not available for review. At time of rotator cuff repair, 3 patients (50%) underwent concomitant procedures, including superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesion repair (1 patient) and posterior labrum débridement (2 patients). A double-row fixation construct was achieved in each case. Review of operative records revealed a mean tear size of 2.1 cm (range, 1.5-3.0 cm) measured anterior to posterior, and all tears involved the supraspinatus and/or infraspinatus tendons. Postoperative rehabilitation included immobilization in a sling for 4 weeks. Hand, wrist, and elbow range-of-motion (ROM) exercises were started immediately to help reduce inflammation. Passive ROM exercises in the plane of the scapula were begun 4 weeks after surgery. Isometric scapular stabilization exercises were also incorporated at that time. Active-assisted ROM exercises were started at about 6 weeks, and isometric strengthening exercises were started at week 8 with progression to eccentric strengthening and weight training at about 3 months. Most pitchers were allowed to begin an interval throwing program at 24 weeks. There were no significant differences in the therapy programs for pitchers who underwent concomitant labral procedures, but the patient who underwent SLAP repair was limited to 30° of external rotation and 90° of forward flexion, with avoidance of active biceps contractions, for the first 6 weeks of rehabilitation.

By mean follow-up of 66.7 months (range, 23.2-94.6 months), 5 pitchers (83%) returned to their preinjury level of competition for at least 1 full season. One player pitched at Minor League Class AA level for about 1 season but was forced to retire because of persistent symptoms related to the shoulder. This pitcher underwent simultaneous rotator cuff and SLAP lesion repair. Of the 5 pitchers who resumed MLB play, none returned to their preoperative pitching productivity; mean number of innings pitched decreased from 1806.5 to 183.7. Three (60%) of these 5 pitchers experienced a slight reduction in performance as measured by earned run average. Interestingly, both players over age 30 years at time of surgery, versus 3 of the 4 pitchers under age 30 years, returned to their preoperative level of competition for at least 1 season. The Table summarizes MLB player data and objective pitching statistics. There were no perioperative complications related to this arthroscopic technique, and there were no glenohumeral ROM deficits at final follow-up.

Discussion

Although the incidence of full-thickness RCTs in professional baseball players is presumably low, available studies suggest that it is a debilitating injury with a poor prognosis for return to high-level athletics. Mazoué and Andrews9 reviewed the outcomes of 16 professional baseball players (12 pitchers, 4 position players) who underwent mini-open repair of full-thickness RCTs that involved more than 90% of the rotator cuff. Fifteen patients underwent mini-open rotator cuff repair using suture anchors in the anatomical footprint along with bone tunnels established near the lateral margin of the greater tuberosity to create a 2-level anatomical repair. One patient was treated with a mini-open repair using suture anchors in the greater tuberosity with a side-side repair of a longitudinal split within the rotator cuff. In the evaluation of outcomes by player position, only 1 pitcher (8%) returned to a competitive level of pitching at a mean follow-up of 67 months. On review of 2 position players with a full-thickness RCT in the dominant shoulder, only 1 (50%) returned to Major League play at a mean follow-up of 62.5 months. The remaining 2 position players underwent surgical repair of the nondominant shoulder, and, not surprisingly, both returned to their previous level of athletic activity without any difficulty. These results should be examined carefully, as the associated pathology in this high-demand cohort should not be discounted. Eleven (almost 92%) of the 12 pitchers had undergone at least 1 previous procedure on the shoulder. Furthermore, at time of full-thickness rotator cuff repair, 9 (75%) of the 12 pitchers were treated for concomitant intra-articular pathology, including SLAP tears, capsular attenuation, and/or labral fraying. In our study, 50% of pitchers underwent an associated labral procedure. Although labral débridement did not have a significant effect on return to play, the 1 pitcher who underwent SLAP repair was not able to return to preinjury level of play.

Tibone and colleagues8 reviewed postoperative outcomes in 45 athletes with rotator cuff pathology. Within their series, 5 professional baseball pitchers with full-thickness tears were treated with open subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair. Two baseball pitchers with RCTs larger than 2 cm underwent open transosseous footprint repair in which the cuff was reinserted using bone tunnels created within the greater tuberosity. At long-term follow-up, only 2 (40%) of the 5 pitchers returned to competitive pitching. Interestingly, both pitchers who underwent transosseous footprint fixation were unable to return to professional baseball.

Overhead athletes require a delicate balance of shoulder mobility and stability to meet the high functional demands of their sports. Significant debate continues as to whether innate alterations in glenohumeral mobility preselect individuals for overhead sports, or if these changes are acquired through adaptations in supporting soft-tissue and osseous structures. Sethi and colleagues14 used an instrumented manual laxity examination to compare anterior-posterior laxity in asymptomatic professional and Division I college baseball players. The authors noted asymmetric anterior-posterior translation (>3 mm) between the throwing shoulder and the nondominant shoulder in 12 (60%) of 20 professional pitchers and 10 (59%) of 17 college pitchers. Although the authors did not correlate translational differences with corresponding shoulder pathology, the observed asymmetry supported the idea that these athletes may experience adaptive glenohumeral changes with repetitive throwing. The association between adaptive changes and shoulder biomechanics has been studied. Burkhart and Lo15 used a cadaveric model to describe the cam effect of the proximal humerus and the biomechanical consequences of a relative reduction in this effect after pathologic changes within the glenohumeral joint (constriction of posteroinferior capsule). They noted that a posterosuperior shift in the glenohumeral contact point in the throwing position can result in anterior capsular redundancy that may contribute to microinstability of the shoulder. This relative laxity increases external rotation, resulting in increased torsional and shear forces at the rotator cuff insertion.16 Ultimately, these abnormal forces may predispose overhead athletes to rotator cuff injury.

Given the available literature, it is clear that full-thickness RCTs are potentially career-ending injuries for professional baseball players. The question arises as to why the results are so poor. Ultimately, the high incidence of concomitant intra-articular pathology associated with full-thickness RCTs underscores the severity of soft-tissue damage sustained with repetitive overhead throwing. Mazoué and Andrews9 proposed the presence of associated labral and capsular pathology as a potential explanation for poor outcomes of surgical repair. Given the myriad of additional pathology observed in each patient, it is difficult to ascertain the precise impact of these injuries on postoperative outcome. However, early diagnosis and aggressive surgical intervention are clearly necessary to prevent accumulative injury. Regarding surgical intervention, both Tibone and colleagues8 and Mazoué and Andrews9 reported use of an open surgical repair technique in which the tendon was repaired to the anatomical footprint. Certainly, the benefits of an all-arthroscopic technique include optimal visualization of the RCT, less perioperative morbidity, and minimal soft-tissue injury. With our arthroscopic technique, the rotator cuff was fixed immediately lateral to the anatomical footprint, thereby leaving the medial aspect of the footprint uncovered. Functionally, the goal of this procedure is to restore the integrity of the rotator cuff without compromising glenohumeral mobility acquired through soft-tissue adaptation. Investigation of the insertional anatomy of the rotator cuff has demonstrated that the supraspinatus tendon inserts about 0.9 mm from the edge of the articular surface, and the infraspinatus insertional footprint tapers away from the articular surface to form the bare area as it extends inferiorly on the greater tuberosity.10 We think preexisting adaptations in glenohumeral anatomy are important for peak performance in this unique population, and even small alterations in the repair location can have deleterious effects on throwing mechanics. Lateralized repair of the cuff precludes potential medialization of the cuff insertion and may facilitate preservation of soft-tissue adaptations that these athletes rely on to achieve extraordinary glenohumeral motion.

Interestingly, with this technique we noted a higher rate of return to MLB play in pitchers over age 30 years. Although several individual factors (eg, player talent level, work ethics, compliance with rehabilitation) may play a role in this finding, it is possible that older, more mature patients may be more willing to assume diminished roles to continue to play. Jones and colleagues17 recently reported similar findings in older MLB pitchers after revision ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction.

This study had several limitations. First, the patient cohort was small (a result of the nature and relatively infrequent incidence of the clinical problem). Second, clinical information was collected retrospectively, which limited our ability to determine precise differences between preoperative and postoperative glenohumeral ROM with this technique. Third, the cohort included patients who demonstrated additional intra-articular (labral) pathology. Although associated pathology is common in this high-demand athletic population, it is clear that advanced pathology (eg, SLAP tears) may affect clinical outcomes, as in our study. Despite these limitations, our study is the largest review of professional baseball players treated for full-thickness rotator cuff injuries with an arthroscopic technique. Overall, the results of this study are promising and call for further clinical and biomechanical evaluation.

Conclusion

Surgical management of rotator cuff injuries in professional baseball players remains an extremely difficult problem. Current studies of full-thickness RCTs highlight these athletes’ poor functional outcomes. These unfavorable results prompted us to alter our surgical technique. Initial outcomes have been encouraging, and extended follow-up in this cohort of patients will provide a more definitive assessment of the success of this technique.

Rotator cuff injuries can be a source of debilitating pain and dysfunction in athletes at all levels, occasionally precluding return to competitive sport. Overhead athletes place extraordinary physiologic demands on the shoulder, as humeral angular velocities of 7000° to 8000° per second and rotational torques higher than 70 Nm have been measured during the baseball pitch.1 Repetitive supraphysiologic loading of the rotator cuff throughout the coordinated phases of throwing can result in a characteristic spectrum of shoulder pathology in overhead throwers. Several studies have demonstrated partial-thickness articular-sided rotator cuff tears (RCTs) in the area of the posterior supraspinatus and anterior infraspinatus tendons.2-4 Although the precise mechanism remains unclear, plausible explanations for the pathogenesis of these injuries include eccentric tensile and shear forces that lead to tendon failure with repetitive throwing, as well as internal impingement (mechanical impingement of the aforementioned tendons against the posterosuperior glenoid at 90° of shoulder abduction and maximum external rotation).5,6

Whereas partial-thickness articular-sided RCTs have been described in overhead athletes with rotator cuff pathology, full-thickness tears are encountered less often.7,8 Accordingly, there is a paucity of literature on clinical outcomes in professional baseball players with these injuries. To our knowledge, only 2 studies have investigated functional outcomes of open surgical repair of full-thickness tears in this population, and the outcomes have been uniformly poor.8,9

An anatomical description of rotator cuff anatomy has demonstrated a consistent pattern of supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon insertion relative to the articular surface, biceps groove, and the bare area of the humerus.10 Using gross and microscopic analyses, the authors noted that the supraspinatus tendon inserted immediately adjacent to the articular margin, and the infraspinatus and teres minor tapered laterally away from the margin to form the bare area. Detailed knowledge of the insertional anatomy of the rotator cuff is important, as surgical repair should recreate the broad footprint to restore normal biomechanics and increase the surface area available for healing.11,12 Medial advancement of the rotator cuff insertion during surgical repair can have deleterious biomechanical effects on glenohumeral motion.11

Given the unfavorable results found after routine open repair of full-thickness tears, we altered our approach to these injuries and adopted an arthroscopic technique in which the tendon is repaired immediately lateral to the anatomical footprint. Research studies have demonstrated that chronic stress from repetitive throwing can lead to attenuation of soft-tissue restraints, and we think preservation of these adaptive changes after surgical repair may be important for these athletes to maintain extraordinary glenohumeral rotation and achieve high throwing velocities.13 We conducted a study to describe the lateralized repair technique for full-thickness RCTs and to report functional outcomes in Major League Baseball (MLB) pitchers treated with this procedure at minimum 2-year follow-up. We hypothesized that use of this novel technique would result in a higher rate of return to preinjury level of play in comparison with open rotator cuff repair in comparable cohorts, as reported in other studies.8,9

Materials and Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we performed a retrospective chart review of MLB players treated by Dr. Altchek. We identified all professional baseball players who received a diagnosis of full-thickness RCT after preoperative magnetic resonance imaging with subsequent confirmation during surgery. Any patient who underwent arthroscopic repair using the lateralized footprint technique was included in the study. Demographic and preoperative injury information was collected from the chart, and final follow-up data were collected at the last available clinic visit. From available team records, we also obtained return-to-play data and objective pitching statistics: seasons played, games played, innings pitched, strikeouts per 9 innings, walks per 9 innings, and earned run average.

Surgical Technique

We routinely perform arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs with the patient under regional anesthesia in the beach-chair position. The operative extremity is placed in a Spider Limb Positioner (Smith & Nephew) to facilitate easy manipulation of the arm throughout the procedure. A standard posterior portal is established, and then an anterior portal is placed in the superolateral aspect of the rotator interval directly anterior to the leading edge of the supraspinatus tendon. A lateral portal created 2 to 3 cm distal to the anterolateral margin of the acromion may be used as an additional working portal. A thorough diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to evaluate the glenohumeral joint for any concomitant intra-articular pathology. Particular attention is directed to inspection of the superior labrum, biceps tendon, and capsuloligamentous structures, as injuries to these structures are often associated with rotator cuff pathology in overhead athletes.

Once presence of an RCT is confirmed, a thorough subacromial bursectomy is performed to help with visualization and inspection of the injury. The tissue is provisionally grasped and mobilized to measure the amount of available tendon excursion. In this unique population, the vast majority of injuries are diagnosed in an expeditious manner, thereby precluding the presence of significant retraction, poor tissue quality, and inadequate mobilization of the tendons. The greater tuberosity is identified, and the area immediately adjacent to the articular margin is abraded with a mechanical shaver to enhance healing potential. For supraspinatus tears, an anchor is placed immediately lateral to the articular margin in the region of the anterior attachment of the rotator cable (Figure 1). The posterior anchor is placed about 10 to 15 mm lateral to the articular margin to reattach the infraspinatus tendon (Figure 2). When the medial row sutures are tied down, anatomical placement of these anchors effectively re-creates the bare area described by Curtis and colleagues10 (Figure 3). In most cases, the medial row sutures are left intact and fixed laterally with a knotless anchor to provide a transosseous equivalent (double-row) repair.

Results

We identified 6 MLB pitchers who underwent arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using the aforementioned technique over an 8-year period. Each patient presented with complaints of debilitating shoulder pain and decreased pitching performance, including loss of throwing accuracy and velocity. There were 4 right-hand–dominant pitchers and 2 left-hand–dominant pitchers; rotator cuff pathology was observed in the dominant pitching arm in each case. Three players were classified as starting pitchers; the other 3 pitched in a relief role. Mean age of all pitchers at time of surgery was 29.8 years (range, 25-37 years). According to records, 2 patients (33%) underwent previous rotator cuff débridement for partial-thickness RCTs before surgical intervention at our institution. Operative information on the depth of the partial-thickness tears observed during the previous procedures was not available for review. At time of rotator cuff repair, 3 patients (50%) underwent concomitant procedures, including superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesion repair (1 patient) and posterior labrum débridement (2 patients). A double-row fixation construct was achieved in each case. Review of operative records revealed a mean tear size of 2.1 cm (range, 1.5-3.0 cm) measured anterior to posterior, and all tears involved the supraspinatus and/or infraspinatus tendons. Postoperative rehabilitation included immobilization in a sling for 4 weeks. Hand, wrist, and elbow range-of-motion (ROM) exercises were started immediately to help reduce inflammation. Passive ROM exercises in the plane of the scapula were begun 4 weeks after surgery. Isometric scapular stabilization exercises were also incorporated at that time. Active-assisted ROM exercises were started at about 6 weeks, and isometric strengthening exercises were started at week 8 with progression to eccentric strengthening and weight training at about 3 months. Most pitchers were allowed to begin an interval throwing program at 24 weeks. There were no significant differences in the therapy programs for pitchers who underwent concomitant labral procedures, but the patient who underwent SLAP repair was limited to 30° of external rotation and 90° of forward flexion, with avoidance of active biceps contractions, for the first 6 weeks of rehabilitation.

By mean follow-up of 66.7 months (range, 23.2-94.6 months), 5 pitchers (83%) returned to their preinjury level of competition for at least 1 full season. One player pitched at Minor League Class AA level for about 1 season but was forced to retire because of persistent symptoms related to the shoulder. This pitcher underwent simultaneous rotator cuff and SLAP lesion repair. Of the 5 pitchers who resumed MLB play, none returned to their preoperative pitching productivity; mean number of innings pitched decreased from 1806.5 to 183.7. Three (60%) of these 5 pitchers experienced a slight reduction in performance as measured by earned run average. Interestingly, both players over age 30 years at time of surgery, versus 3 of the 4 pitchers under age 30 years, returned to their preoperative level of competition for at least 1 season. The Table summarizes MLB player data and objective pitching statistics. There were no perioperative complications related to this arthroscopic technique, and there were no glenohumeral ROM deficits at final follow-up.

Discussion

Although the incidence of full-thickness RCTs in professional baseball players is presumably low, available studies suggest that it is a debilitating injury with a poor prognosis for return to high-level athletics. Mazoué and Andrews9 reviewed the outcomes of 16 professional baseball players (12 pitchers, 4 position players) who underwent mini-open repair of full-thickness RCTs that involved more than 90% of the rotator cuff. Fifteen patients underwent mini-open rotator cuff repair using suture anchors in the anatomical footprint along with bone tunnels established near the lateral margin of the greater tuberosity to create a 2-level anatomical repair. One patient was treated with a mini-open repair using suture anchors in the greater tuberosity with a side-side repair of a longitudinal split within the rotator cuff. In the evaluation of outcomes by player position, only 1 pitcher (8%) returned to a competitive level of pitching at a mean follow-up of 67 months. On review of 2 position players with a full-thickness RCT in the dominant shoulder, only 1 (50%) returned to Major League play at a mean follow-up of 62.5 months. The remaining 2 position players underwent surgical repair of the nondominant shoulder, and, not surprisingly, both returned to their previous level of athletic activity without any difficulty. These results should be examined carefully, as the associated pathology in this high-demand cohort should not be discounted. Eleven (almost 92%) of the 12 pitchers had undergone at least 1 previous procedure on the shoulder. Furthermore, at time of full-thickness rotator cuff repair, 9 (75%) of the 12 pitchers were treated for concomitant intra-articular pathology, including SLAP tears, capsular attenuation, and/or labral fraying. In our study, 50% of pitchers underwent an associated labral procedure. Although labral débridement did not have a significant effect on return to play, the 1 pitcher who underwent SLAP repair was not able to return to preinjury level of play.

Tibone and colleagues8 reviewed postoperative outcomes in 45 athletes with rotator cuff pathology. Within their series, 5 professional baseball pitchers with full-thickness tears were treated with open subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair. Two baseball pitchers with RCTs larger than 2 cm underwent open transosseous footprint repair in which the cuff was reinserted using bone tunnels created within the greater tuberosity. At long-term follow-up, only 2 (40%) of the 5 pitchers returned to competitive pitching. Interestingly, both pitchers who underwent transosseous footprint fixation were unable to return to professional baseball.

Overhead athletes require a delicate balance of shoulder mobility and stability to meet the high functional demands of their sports. Significant debate continues as to whether innate alterations in glenohumeral mobility preselect individuals for overhead sports, or if these changes are acquired through adaptations in supporting soft-tissue and osseous structures. Sethi and colleagues14 used an instrumented manual laxity examination to compare anterior-posterior laxity in asymptomatic professional and Division I college baseball players. The authors noted asymmetric anterior-posterior translation (>3 mm) between the throwing shoulder and the nondominant shoulder in 12 (60%) of 20 professional pitchers and 10 (59%) of 17 college pitchers. Although the authors did not correlate translational differences with corresponding shoulder pathology, the observed asymmetry supported the idea that these athletes may experience adaptive glenohumeral changes with repetitive throwing. The association between adaptive changes and shoulder biomechanics has been studied. Burkhart and Lo15 used a cadaveric model to describe the cam effect of the proximal humerus and the biomechanical consequences of a relative reduction in this effect after pathologic changes within the glenohumeral joint (constriction of posteroinferior capsule). They noted that a posterosuperior shift in the glenohumeral contact point in the throwing position can result in anterior capsular redundancy that may contribute to microinstability of the shoulder. This relative laxity increases external rotation, resulting in increased torsional and shear forces at the rotator cuff insertion.16 Ultimately, these abnormal forces may predispose overhead athletes to rotator cuff injury.

Given the available literature, it is clear that full-thickness RCTs are potentially career-ending injuries for professional baseball players. The question arises as to why the results are so poor. Ultimately, the high incidence of concomitant intra-articular pathology associated with full-thickness RCTs underscores the severity of soft-tissue damage sustained with repetitive overhead throwing. Mazoué and Andrews9 proposed the presence of associated labral and capsular pathology as a potential explanation for poor outcomes of surgical repair. Given the myriad of additional pathology observed in each patient, it is difficult to ascertain the precise impact of these injuries on postoperative outcome. However, early diagnosis and aggressive surgical intervention are clearly necessary to prevent accumulative injury. Regarding surgical intervention, both Tibone and colleagues8 and Mazoué and Andrews9 reported use of an open surgical repair technique in which the tendon was repaired to the anatomical footprint. Certainly, the benefits of an all-arthroscopic technique include optimal visualization of the RCT, less perioperative morbidity, and minimal soft-tissue injury. With our arthroscopic technique, the rotator cuff was fixed immediately lateral to the anatomical footprint, thereby leaving the medial aspect of the footprint uncovered. Functionally, the goal of this procedure is to restore the integrity of the rotator cuff without compromising glenohumeral mobility acquired through soft-tissue adaptation. Investigation of the insertional anatomy of the rotator cuff has demonstrated that the supraspinatus tendon inserts about 0.9 mm from the edge of the articular surface, and the infraspinatus insertional footprint tapers away from the articular surface to form the bare area as it extends inferiorly on the greater tuberosity.10 We think preexisting adaptations in glenohumeral anatomy are important for peak performance in this unique population, and even small alterations in the repair location can have deleterious effects on throwing mechanics. Lateralized repair of the cuff precludes potential medialization of the cuff insertion and may facilitate preservation of soft-tissue adaptations that these athletes rely on to achieve extraordinary glenohumeral motion.

Interestingly, with this technique we noted a higher rate of return to MLB play in pitchers over age 30 years. Although several individual factors (eg, player talent level, work ethics, compliance with rehabilitation) may play a role in this finding, it is possible that older, more mature patients may be more willing to assume diminished roles to continue to play. Jones and colleagues17 recently reported similar findings in older MLB pitchers after revision ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction.

This study had several limitations. First, the patient cohort was small (a result of the nature and relatively infrequent incidence of the clinical problem). Second, clinical information was collected retrospectively, which limited our ability to determine precise differences between preoperative and postoperative glenohumeral ROM with this technique. Third, the cohort included patients who demonstrated additional intra-articular (labral) pathology. Although associated pathology is common in this high-demand athletic population, it is clear that advanced pathology (eg, SLAP tears) may affect clinical outcomes, as in our study. Despite these limitations, our study is the largest review of professional baseball players treated for full-thickness rotator cuff injuries with an arthroscopic technique. Overall, the results of this study are promising and call for further clinical and biomechanical evaluation.

Conclusion

Surgical management of rotator cuff injuries in professional baseball players remains an extremely difficult problem. Current studies of full-thickness RCTs highlight these athletes’ poor functional outcomes. These unfavorable results prompted us to alter our surgical technique. Initial outcomes have been encouraging, and extended follow-up in this cohort of patients will provide a more definitive assessment of the success of this technique.

1. Dillman CJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of pitching with emphasis upon shoulder kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(2):402-408.

2. Andrews JR, Broussard TS, Carson WG. Arthroscopy of the shoulder in the management of partial tears of the rotator cuff: a preliminary report. Arthroscopy. 1985;1(2):117-122.

3. Paley KJ, Jobe FW, Pink MM, Kvitne RS, ElAttrache NS. Arthroscopic findings in the overhead throwing athlete: evidence for posterior internal impingement of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(1):35-40.

4. Nakagawa S, Yoneda M, Hayashida K, Wakitani S, Okamura K. Greater tuberosity notch: an important indicator of articular-side partial rotator cuff tears in the shoulders of throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(6):762-770.

5. Walch G, Boileau P, Noel E, Donell ST. Impingement of the deep surface of the supraspinatus tendon on the posterosuperior glenoid rim: an arthroscopic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1(5):238-245.

6. Halbrecht JL, Tirman P, Atkin D. Internal impingement of the shoulder: comparison of findings between the throwing and nonthrowing shoulders of college baseball players. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(3):253-258.

7. Reynolds SB, Dugas JR, Cain EL, McMichael CS, Andrews JR. Debridement of small partial-thickness rotator cuff tears in elite overhead throwers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):614-621.

8. Tibone JE, Elrod B, Jobe FW, et al. Surgical treatment of tears of the rotator cuff in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(6):887-891.

9. Mazoué C, Andrews JR. Repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34():182-189.

10. Curtis AS, Burbank KM, Tierney JJ, Scheller AD, Curran AR. The insertional footprint of the rotator cuff: an anatomic study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(6):603-609.

11. Liu J, Hughes RE, O’Driscoll SW, An K. Biomechanical effect of medial advancement of the supraspinatus tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(6):853-859.

12. Lo IK, Burkhart SS. Double row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: re-establishing the footprint of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(9):1035-1042.

13. Borsa PA, Laudner KG, Sauers EL. Mobility and stability adaptations in the shoulder of the overhead athlete: a theoretical and evidence-based perspective. Sports Med. 2008;38(1):17-36.

14. Sethi PM, Tibone JE, Lee TQ. Quantitative assessment of glenohumeral translation in baseball players: a comparison of pitchers versus nonpitching athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(7):1711-1715.

15. Burkhart SS, Lo IK. The cam effect of the proximal humerus: its role in the production of relative capsular redundancy of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(3):241-246.

16. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology. Part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):404-420.

17. Jones KJ, Conte S, Patterson N, ElAttrache NS, Dines JS. Functional outcomes following revision ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in Major League Baseball pitchers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(5):642-646.

1. Dillman CJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of pitching with emphasis upon shoulder kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(2):402-408.

2. Andrews JR, Broussard TS, Carson WG. Arthroscopy of the shoulder in the management of partial tears of the rotator cuff: a preliminary report. Arthroscopy. 1985;1(2):117-122.

3. Paley KJ, Jobe FW, Pink MM, Kvitne RS, ElAttrache NS. Arthroscopic findings in the overhead throwing athlete: evidence for posterior internal impingement of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(1):35-40.

4. Nakagawa S, Yoneda M, Hayashida K, Wakitani S, Okamura K. Greater tuberosity notch: an important indicator of articular-side partial rotator cuff tears in the shoulders of throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(6):762-770.

5. Walch G, Boileau P, Noel E, Donell ST. Impingement of the deep surface of the supraspinatus tendon on the posterosuperior glenoid rim: an arthroscopic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1(5):238-245.

6. Halbrecht JL, Tirman P, Atkin D. Internal impingement of the shoulder: comparison of findings between the throwing and nonthrowing shoulders of college baseball players. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(3):253-258.

7. Reynolds SB, Dugas JR, Cain EL, McMichael CS, Andrews JR. Debridement of small partial-thickness rotator cuff tears in elite overhead throwers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):614-621.

8. Tibone JE, Elrod B, Jobe FW, et al. Surgical treatment of tears of the rotator cuff in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(6):887-891.

9. Mazoué C, Andrews JR. Repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34():182-189.

10. Curtis AS, Burbank KM, Tierney JJ, Scheller AD, Curran AR. The insertional footprint of the rotator cuff: an anatomic study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(6):603-609.

11. Liu J, Hughes RE, O’Driscoll SW, An K. Biomechanical effect of medial advancement of the supraspinatus tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(6):853-859.

12. Lo IK, Burkhart SS. Double row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: re-establishing the footprint of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(9):1035-1042.

13. Borsa PA, Laudner KG, Sauers EL. Mobility and stability adaptations in the shoulder of the overhead athlete: a theoretical and evidence-based perspective. Sports Med. 2008;38(1):17-36.

14. Sethi PM, Tibone JE, Lee TQ. Quantitative assessment of glenohumeral translation in baseball players: a comparison of pitchers versus nonpitching athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(7):1711-1715.

15. Burkhart SS, Lo IK. The cam effect of the proximal humerus: its role in the production of relative capsular redundancy of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(3):241-246.

16. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology. Part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):404-420.

17. Jones KJ, Conte S, Patterson N, ElAttrache NS, Dines JS. Functional outcomes following revision ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in Major League Baseball pitchers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(5):642-646.