User login

Platelet-Rich Plasma Can Be Used to Successfully Treat Elbow Ulnar Collateral Ligament Insufficiency in High-Level Throwers

For overhead athletes, elbow ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) insufficiency is a potential career-ending injury. Baseball players with UCL insufficiency typically complain of medial-sided elbow pain that affects their ability to throw. Loss of velocity, loss of control, difficulty warming up, and pain while throwing are all symptoms of UCL injury.

Classically, nonoperative treatment of UCL injuries involves activity modification, use of anti-inflammatory medication, and a structured physical therapy program. Asymptomatic players can return to throwing after a structured interval throwing program. Rettig and colleagues1 found a 42% rate of success in conservatively treating UCL injuries in throwing athletes. UCL reconstruction is reserved for players with complete tears of the UCL or with partial tears after failed conservative treatment. Several techniques have been used to reconstruct the ligament, but successful outcomes depend on a long rehabilitation process. According to most published series, 85% to 90% of athletes who had UCL reconstruction returned to their previous level of play, but it took, on average, 9 to 12 months.2,3 This prolonged recovery period is one reason that some older professional baseball players, as well as casual high school and college players, elect to forgo surgery.

Over the past few years, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has garnered attention as a bridge between conservative treatment and surgery. PRP refers to a sample of autologous blood that contains a platelet concentration higher than baseline levels. This sample often has a 3 to 5 times increase in growth factor concentration.4-6 Initial studies focused on its ability to successfully treat lateral epicondylitis.7-9 More recent clinical work has shown that PRP can potentially enhance healing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,10-14 rotator cuff repair,15-17 and subacromial decompression.11,18-23 If PRP could be used to successfully treat UCL insufficiency that is refractory to conservative treatment, then year-long recovery periods could be avoided. This could potentially prolong certain athletes’ careers or, at the very least, allow them to return to play much sooner. In the present case series, we hypothesized that PRP injections could be used to successfully treat partial UCL tears in high-level throwing athletes, obviating the need for surgery and its associated prolonged recovery period.

Materials and Methods

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this retrospective study of 44 baseball players treated with PRP injections for partial-thickness UCL tears.

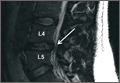

Patients provided written informed consent. They were diagnosed with UCL insufficiency by physical examination, and findings were confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). After diagnosis, all throwers underwent a trial of conservative treatment that included rest, activity modification, use of anti-inflammatory medication, and physical therapy followed by an attempt to return to throwing using an interval throwing program.

Study inclusion criteria were physical examinations and MRI results consistent with UCL insufficiency, and failure of the conservative treatment plan described.

Patients were injected using the Autologous Conditioned Plasma system (Arthrex). PRP solutions were prepared according to manufacturer guidelines. After the elbow was prepared sterilely, the UCL was injected at the location of the tear. Typically, 3 mL of PRP was injected into the elbow. Sixteen patients had 1 injection, 6 had 2, and 22 had 3. Repeat injections were considered for recalcitrant pain after 3 weeks.

After injection, patients used acetaminophen and ice for pain control. Anti-inflammatory medications were avoided for a minimum of 2 weeks after injection. Typical postinjection therapy protocol consisted of rest followed by progressive stretching and strengthening for about 4 to 6 weeks before the start of an interval throwing program. Although there is no well-defined postinjection recovery protocol, as a general rule rest was prescribed for the first 2 weeks, followed by a progressive stretching and strengthening program for the next month. Patients who were asymptomatic subjectively and clinically—negative moving valgus stress test, negative milking maneuver, no pain with valgus stress—were started on an interval throwing program.

Final follow-up involved a physical examination. Results were classified according to a modified version of the Conway Scale12,24-26: excellent (return to preinjury level of competition or performance), good (return to play at a lower level of competition or performance or, specifically for baseball players, ability to throw in daily batting practice), fair (able to play recreationally), and poor (unable to return to previous sport at any level).

By final follow-up, all patients had completed their postoperative rehabilitation protocol, and all had at least tried to return to their previous activities. No patients were lost to follow-up.

Results

Of the 44 baseball players, 6 were professional, 14 were in college, and 24 were in high school. There were 36 pitchers and 8 position players. Mean age was 17.3 years (range, 16-28 years). All patients were available for follow-up after injection (mean, 11 months). Fifteen of the 44 players had an excellent outcome (34%), 17 had a good outcome, 2 had a fair outcome, and 10 had a poor outcome. After injection, 4 (67%) of the 6 professional baseball players returned to professional play. Five (36%) of the 14 college players had an excellent outcome, and 4 (17%) of the 24 high school players had an excellent outcome. Of the 8 position players, 4 had an excellent outcome, 3 had a good outcome, and 1 had a poor outcome.

Before treatment, all patients had medial-sided elbow pain over the UCL inhibiting their ability to throw. Mean duration of symptoms before injection was 8.8 months (range, 1-36 months). There was no correlation between symptom duration and any outcome measure. On MRI, 29 patients showed partial tears: 22 proximally based and 7 distally based. The other 15 patients had diffuse signal without partial tear. All 7 patients with distally based partial tears and 3 of the patients with proximally based partial tears had a poor outcome. Overall, there were 6 excellent, 7 good, and 2 fair outcomes in the partial-tear group. In the patients with diffuse signal without partial tear, there were 9 excellent and 10 good outcomes.

Mean time from injection to return to throwing was 5 weeks, and mean time to return to competition was 12 weeks (range, 5-24 weeks). The 1 player who returned at 5 weeks was a professional relief pitcher whose team was in the playoffs. He has now pitched for an additional 2 baseball seasons without elbow difficulty.

There were no injection-related complications.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report documenting successful PRP treatment of UCL insufficiency. In this study, 73% of players who had failed a course of conservative treatment had good to excellent outcomes with PRP injection.

Data on successful nonoperative treatment of UCL injuries are limited. Rettig and colleagues1 treated 31 throwing athletes’ UCL injuries with a supervised rehabilitation program. Treatment included rest, use of anti-inflammatory medication, progressive strengthening, and an interval throwing program. Only 41% of the athletes returned to their previous level of play, and it took, on average, 24.5 weeks. There was no significant difference in age or in duration or acuity of symptoms between those who returned to play and those whose conservative treatment failed.

Surgical reconstruction of UCL injuries has been very successful, with upward of 90% of athletes returning to previous level of play.3,27The procedure, however, is not without associated complications, including retear of the ligament, stiffness, ulnar nerve injury, and fracture.27-29 In addition, even when successful, the procedure requires that athletes take 9 to 12 months to recover before returning to competition at their previous level.

Savoie and colleagues,30 in their recent study on UCL repairs, highlighted an important fact that is often overlooked when reviewing the literature on UCL tears. Most of the literature on these injuries focuses on college and professional baseball players in whom ligament damage is often extensive, precluding repair. In contrast to prior reports, Savoie and colleagues30 found excellent results in 93% of their young athletes who underwent UCL repair. It is possible that their results can be attributed to the fact that many of their athletes had tears isolated to one area of the ligament, as opposed to generalized ligament incompetence. Our improved results vis-à-vis other reports on conservative management may be attributable to the same phenomenon.

PRP has garnered much attention in the literature and media because of its potential to enhance healing of tendons and ligaments; in some cases, it can obviate the need for surgery. After failure of other nonoperative measures in 15 patients with elbow epicondylitis, Mishra and Pavelko8 treated each patient with a single PRP injection. They prepared the PRP using the GPS III system (Biomet). At final follow-up, 93% improvement was seen. Clearly, their experiment had design flaws: It was nonblinded, and 3 of the 5 patients in the control group treated with bupivacaine injection withdrew from the experiment. Despite its shortcomings, their study became the impetus for several other studies.

A larger, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial comparing PRP and cortisone injections for lateral epicondylitis in 100 patients is under way, and preliminary results have been published.9 A minimum of 6 months after injection, patients who received PRP showed more improvement in visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores and Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire scores. In another large, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial, patients with chronic lateral epicondylitis had significant improvements in VAS pain scores and DASH scores relative to patients injected with corticosteroids with a 2-year follow-up.31 Similarly, Thanasas and colleagues32 found significantly reduced VAS pain scores in patients injected with PRP versus autologous whole blood. Another study demonstrated improved tendon morphology using ultrasound imaging 6 months after PRP injection.33

Contrary to these positive results, Krogh and colleagues34 found that a single injection of PRP or glucocorticoid was not significantly superior to a saline injection for reducing pain and disability over a 3-month period in patients with lateral epicondylitis. Their study, however, had major flaws. Its original design called for a 12-month follow-up, but there was massive dropout in all 3 treatment arms, necessitating reporting of only 3-month data. In addition, 60% of the patients in the glucocorticoid group were not naïve to this treatment, so definitive conclusions about the efficacy of glucocorticoids could not be made.

In the present study, we successfully treated partial ligament tears with PRP injections. Sixty-seven percent of our baseball players returned to play at a mean of 4 months, much earlier than the 9 to 12 months typically required after ligament reconstruction. Many athletes, such as high school baseball players or aging veteran professional baseball players, do not have the luxury of 12 months for recovery. Therefore, this select group of patients clearly has a limited window of opportunity to return to play. In fact, these patients might be ideal candidates for PRP injections for UCL injuries. Return-to-play rates, however, differed significantly among professional players and nonprofessional players. The difference may be attributable to professional players’ conditioning, quality of physical therapy, extrinsic motivation, and other intangible factors. Four (67%) of our 6 professional baseball players returned to professional play after injection, whereas only 36% of college players and 17% of high school players had excellent outcomes.

Limitations

The present study had several weaknesses, several of which are inherent to PRP studies conducted so far. It was not a prospective, randomized controlled trial. It is important to note that PRP treatment in diseased tissue may have some drawbacks, as its success depends on the ability of healing tissue to use concentrated growth factors and cytokines to proliferate.35 Thus, a chronically injured ligament with depleted active cells may have a diminished response to PRP. Another limitation of this study is that we evaluated outcomes based on return to play using the Conway Scale, which is well reported but not validated. Despite the potential weaknesses of this outcome scale, it has become the benchmark for measuring the success of outcomes of UCL reconstruction. Furthermore, we did not measure patients’ satisfaction with the treatment. Players who could not return to their preinjury level of play may have considered the treatment a failure regardless of their ability to continue throwing. Last, MRI was not repeated to document ligament healing. We did not routinely perform a second MRI because we thought it would not affect treatment. Several series have found a high incidence of abnormal signal in baseball players’ UCLs. In this group of patients, the most important outcome is return to previous level of competition.

This study raised several questions. Is one PRP brand better than another? Should more than 1 injection be given? What is the ideal postinjection protocol? Clearly, larger, prospective, randomized controlled studies are needed to truly elucidate the potential role of PRP in the treatment algorithm for UCL injury. Nevertheless, in certain cases in which traditional conservative measures have failed and patients do not have the luxury of rehabilitating for 9 to 12 months after surgery, PRP may be a viable treatment option.

Conclusion

In this study, use of PRP in the treatment of UCL insufficiency produced outcomes much better than earlier reported outcomes of conservative treatment of these injuries. PRP injections may be particularly beneficial in young athletes who have sustained acute damage to an isolated part of the ligament and in athletes unwilling or unable to undergo the extended rehabilitation required after surgical reconstruction of the ligament.

1. Rettig AC, Sherrill C, Snead DS, Mendler JC, Mieling P. Nonoperative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries in throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(1):15-17.

2. Eygendaal D, Rahussen FT, Diercks RL. Biomechanics of the elbow joint in tennis players and relation to pathology. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(11):820-823.

3. Bowers AL, Dines JS, Dines DM, Altchek DW. Elbow medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: clinical relevance and the docking technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):110-117.

5. Kibler WB. Biomechanical analysis of the shoulder during tennis activities. Clin Sports Med. 1995;14(1):79-85.

5. Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(4):489-496.

6. Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what is PRP and what is not PRP? Implant Dent. 2001;10(4):225-228.

7. Elliott B, Fleisig G, Nicholls R, Escamilia R. Technique effects on upper limb loading in the tennis serve. J Sci Med Sport. 2003;6(1):76-87.

8. Mishra A, Pavelko T. Treatment of chronic elbow tendinosis with buffered platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(11):1774-1778.

9. Mishra A, Woodall J Jr, Vieira A. Treatment of tendon and muscle using platelet-rich plasma. Clin Sports Med. 2009;28(1):113-125.

10. Kovacs MS. Applied physiology of tennis performance. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(5):381-386.

11. Xie X, Wu H, Zhao S, Xie G, Huangfu X, Zhao J. The effect of platelet-rich plasma on patterns of gene expression in a dog model of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Surg Res. 2013;180(1):80-88.

12. Pluim BM, Staal JB, Windler GE, Jayanthi N. Tennis injuries: occurrence, aetiology, and prevention. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(5):415-423.

13. Xie X, Zhao S, Wu H, et al. Platelet-rich plasma enhances autograft revascularization and reinnervation in a dog model of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Surg Res. 2013;183(1):214-222.

14. Lopez-Vidriero E, Goulding KA, Simon DA, Sanchez M, Johnson DH. The use of platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopy and sports medicine: optimizing the healing environment. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(2):269-278.

15. Jo CH, Shin JS, Shin WH, Lee SY, Yoon KS, Shin S. Platelet-rich plasma for arthroscopic repair of medium to large rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(9):2102-2110.

16. Jo CH, Shin JS, Lee YG, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for arthroscopic repair of large to massive rotator cuff tears: a randomized, single-blinded, parallel-group trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2240-2248.

17. Randelli P, Arrigoni P, Ragone V, Aliprandi A, Cabitza P. Platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective RCT study, 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):518-528.

18. Randelli P, Arrigoni P, Ragone V, Aliprandi A, Cabitza P. Platelet rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective RCT study, 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):518-528.

19. Barber FA, Hrnack SA, Snyder SJ, Hapa O. Rotator cuff repair healing influenced by platelet-rich plasma construct augmentation. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(8):1029-1035.

20. Jo CH, Kim JE, Yoon KS, et al. Does platelet-rich plasma accelerate recovery after rotator cuff repair? A prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2082-2090.

21. Jo CH, Kim JE, Yoon KS, Shin S. Platelet-rich plasma stimulates cell proliferation and enhances matrix gene expression and synthesis in tenocytes from human rotator cuff tendons with degenerative tears. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1035-1045.

22. Chahal J, Van Thiel GS, Mall N, et al. The role of platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a systematic review with quantitative synthesis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1718-1727.

23. Mei-Dan O, Carmont MR. The role of platelet-rich plasma in rotator cuff repair. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19(3):244-250.

24. Dines JS, ElAttrache NS, Conway JE, Smith W, Ahmad CS. Clinical outcomes of the DANE TJ technique to treat ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(12):2039-2044.

25. Hutchinson MR, Laprade RF, Burnett QM 2nd, Moss R, Terpstra J. Injury surveillance at the USTA boys’ tennis championships: a 6-yr study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(6):826-830.

26. Winge S, Jørgensen U, Nielsen A. Epidemiology of injuries in Danish championship tennis. Int J Sports Med. 1989;10(5):368-371.

27. Safran MR, Hutchinson MR, Moss R, Albrandt J. A comparison of injuries in elite boys and girls tennis players. Paper presented at: 9th Annual Meeting of the Society of Tennis Medicine and Science; March 1999; Indian Wells, CA.

28. Cain EL, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, et al. Outcome of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow in 1281 athletes: results in 743 athletes with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2426-2434.

29. Dines JS, Yocum LA, Frank JB, ElAttrache NS, Gambardella RA, Jobe FW. Revision surgery for failed elbow medial collateral ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1061-1065.

30. Savoie FH, Trenhaile SW, Roberts J, Field LD, Ramsey JR. Primary repair of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in young athletes: a case series of injuries to the proximal and distal ends of the ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1066-1072.

31. Gosens T, Peerbooms JC, van Laar W, Oudsten den BL. Ongoing positive effect of platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection in lateral epicondylitis: a double-blind randomized controlled trial with 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1200-1208.

32. Thanasas C, Papadimitriou G, Charalambidis C, Paraskevopoulos I, Papanikolaou A. Platelet-rich plasma versus autologous whole blood for the treatment of chronic lateral elbow epicondylitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2130-2134.

33. Chaudhury S, La Lama de M, Adler RS, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: sonographic assessment of tendon morphology and vascularity (pilot study). Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(1):91-97.

34. Krogh TP, Fredberg U, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Christensen R, Jensen P, Ellingsen T. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with platelet-rich plasma, glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):625-635.

35. Anz AW, Hackel JG, Nilssen EC, Andrews JR. Application of biologics in the treatment of the rotator cuff, meniscus, cartilage, and osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(2):68-79.

For overhead athletes, elbow ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) insufficiency is a potential career-ending injury. Baseball players with UCL insufficiency typically complain of medial-sided elbow pain that affects their ability to throw. Loss of velocity, loss of control, difficulty warming up, and pain while throwing are all symptoms of UCL injury.

Classically, nonoperative treatment of UCL injuries involves activity modification, use of anti-inflammatory medication, and a structured physical therapy program. Asymptomatic players can return to throwing after a structured interval throwing program. Rettig and colleagues1 found a 42% rate of success in conservatively treating UCL injuries in throwing athletes. UCL reconstruction is reserved for players with complete tears of the UCL or with partial tears after failed conservative treatment. Several techniques have been used to reconstruct the ligament, but successful outcomes depend on a long rehabilitation process. According to most published series, 85% to 90% of athletes who had UCL reconstruction returned to their previous level of play, but it took, on average, 9 to 12 months.2,3 This prolonged recovery period is one reason that some older professional baseball players, as well as casual high school and college players, elect to forgo surgery.

Over the past few years, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has garnered attention as a bridge between conservative treatment and surgery. PRP refers to a sample of autologous blood that contains a platelet concentration higher than baseline levels. This sample often has a 3 to 5 times increase in growth factor concentration.4-6 Initial studies focused on its ability to successfully treat lateral epicondylitis.7-9 More recent clinical work has shown that PRP can potentially enhance healing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,10-14 rotator cuff repair,15-17 and subacromial decompression.11,18-23 If PRP could be used to successfully treat UCL insufficiency that is refractory to conservative treatment, then year-long recovery periods could be avoided. This could potentially prolong certain athletes’ careers or, at the very least, allow them to return to play much sooner. In the present case series, we hypothesized that PRP injections could be used to successfully treat partial UCL tears in high-level throwing athletes, obviating the need for surgery and its associated prolonged recovery period.

Materials and Methods

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this retrospective study of 44 baseball players treated with PRP injections for partial-thickness UCL tears.

Patients provided written informed consent. They were diagnosed with UCL insufficiency by physical examination, and findings were confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). After diagnosis, all throwers underwent a trial of conservative treatment that included rest, activity modification, use of anti-inflammatory medication, and physical therapy followed by an attempt to return to throwing using an interval throwing program.

Study inclusion criteria were physical examinations and MRI results consistent with UCL insufficiency, and failure of the conservative treatment plan described.

Patients were injected using the Autologous Conditioned Plasma system (Arthrex). PRP solutions were prepared according to manufacturer guidelines. After the elbow was prepared sterilely, the UCL was injected at the location of the tear. Typically, 3 mL of PRP was injected into the elbow. Sixteen patients had 1 injection, 6 had 2, and 22 had 3. Repeat injections were considered for recalcitrant pain after 3 weeks.

After injection, patients used acetaminophen and ice for pain control. Anti-inflammatory medications were avoided for a minimum of 2 weeks after injection. Typical postinjection therapy protocol consisted of rest followed by progressive stretching and strengthening for about 4 to 6 weeks before the start of an interval throwing program. Although there is no well-defined postinjection recovery protocol, as a general rule rest was prescribed for the first 2 weeks, followed by a progressive stretching and strengthening program for the next month. Patients who were asymptomatic subjectively and clinically—negative moving valgus stress test, negative milking maneuver, no pain with valgus stress—were started on an interval throwing program.

Final follow-up involved a physical examination. Results were classified according to a modified version of the Conway Scale12,24-26: excellent (return to preinjury level of competition or performance), good (return to play at a lower level of competition or performance or, specifically for baseball players, ability to throw in daily batting practice), fair (able to play recreationally), and poor (unable to return to previous sport at any level).

By final follow-up, all patients had completed their postoperative rehabilitation protocol, and all had at least tried to return to their previous activities. No patients were lost to follow-up.

Results

Of the 44 baseball players, 6 were professional, 14 were in college, and 24 were in high school. There were 36 pitchers and 8 position players. Mean age was 17.3 years (range, 16-28 years). All patients were available for follow-up after injection (mean, 11 months). Fifteen of the 44 players had an excellent outcome (34%), 17 had a good outcome, 2 had a fair outcome, and 10 had a poor outcome. After injection, 4 (67%) of the 6 professional baseball players returned to professional play. Five (36%) of the 14 college players had an excellent outcome, and 4 (17%) of the 24 high school players had an excellent outcome. Of the 8 position players, 4 had an excellent outcome, 3 had a good outcome, and 1 had a poor outcome.

Before treatment, all patients had medial-sided elbow pain over the UCL inhibiting their ability to throw. Mean duration of symptoms before injection was 8.8 months (range, 1-36 months). There was no correlation between symptom duration and any outcome measure. On MRI, 29 patients showed partial tears: 22 proximally based and 7 distally based. The other 15 patients had diffuse signal without partial tear. All 7 patients with distally based partial tears and 3 of the patients with proximally based partial tears had a poor outcome. Overall, there were 6 excellent, 7 good, and 2 fair outcomes in the partial-tear group. In the patients with diffuse signal without partial tear, there were 9 excellent and 10 good outcomes.

Mean time from injection to return to throwing was 5 weeks, and mean time to return to competition was 12 weeks (range, 5-24 weeks). The 1 player who returned at 5 weeks was a professional relief pitcher whose team was in the playoffs. He has now pitched for an additional 2 baseball seasons without elbow difficulty.

There were no injection-related complications.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report documenting successful PRP treatment of UCL insufficiency. In this study, 73% of players who had failed a course of conservative treatment had good to excellent outcomes with PRP injection.

Data on successful nonoperative treatment of UCL injuries are limited. Rettig and colleagues1 treated 31 throwing athletes’ UCL injuries with a supervised rehabilitation program. Treatment included rest, use of anti-inflammatory medication, progressive strengthening, and an interval throwing program. Only 41% of the athletes returned to their previous level of play, and it took, on average, 24.5 weeks. There was no significant difference in age or in duration or acuity of symptoms between those who returned to play and those whose conservative treatment failed.

Surgical reconstruction of UCL injuries has been very successful, with upward of 90% of athletes returning to previous level of play.3,27The procedure, however, is not without associated complications, including retear of the ligament, stiffness, ulnar nerve injury, and fracture.27-29 In addition, even when successful, the procedure requires that athletes take 9 to 12 months to recover before returning to competition at their previous level.

Savoie and colleagues,30 in their recent study on UCL repairs, highlighted an important fact that is often overlooked when reviewing the literature on UCL tears. Most of the literature on these injuries focuses on college and professional baseball players in whom ligament damage is often extensive, precluding repair. In contrast to prior reports, Savoie and colleagues30 found excellent results in 93% of their young athletes who underwent UCL repair. It is possible that their results can be attributed to the fact that many of their athletes had tears isolated to one area of the ligament, as opposed to generalized ligament incompetence. Our improved results vis-à-vis other reports on conservative management may be attributable to the same phenomenon.

PRP has garnered much attention in the literature and media because of its potential to enhance healing of tendons and ligaments; in some cases, it can obviate the need for surgery. After failure of other nonoperative measures in 15 patients with elbow epicondylitis, Mishra and Pavelko8 treated each patient with a single PRP injection. They prepared the PRP using the GPS III system (Biomet). At final follow-up, 93% improvement was seen. Clearly, their experiment had design flaws: It was nonblinded, and 3 of the 5 patients in the control group treated with bupivacaine injection withdrew from the experiment. Despite its shortcomings, their study became the impetus for several other studies.

A larger, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial comparing PRP and cortisone injections for lateral epicondylitis in 100 patients is under way, and preliminary results have been published.9 A minimum of 6 months after injection, patients who received PRP showed more improvement in visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores and Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire scores. In another large, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial, patients with chronic lateral epicondylitis had significant improvements in VAS pain scores and DASH scores relative to patients injected with corticosteroids with a 2-year follow-up.31 Similarly, Thanasas and colleagues32 found significantly reduced VAS pain scores in patients injected with PRP versus autologous whole blood. Another study demonstrated improved tendon morphology using ultrasound imaging 6 months after PRP injection.33

Contrary to these positive results, Krogh and colleagues34 found that a single injection of PRP or glucocorticoid was not significantly superior to a saline injection for reducing pain and disability over a 3-month period in patients with lateral epicondylitis. Their study, however, had major flaws. Its original design called for a 12-month follow-up, but there was massive dropout in all 3 treatment arms, necessitating reporting of only 3-month data. In addition, 60% of the patients in the glucocorticoid group were not naïve to this treatment, so definitive conclusions about the efficacy of glucocorticoids could not be made.

In the present study, we successfully treated partial ligament tears with PRP injections. Sixty-seven percent of our baseball players returned to play at a mean of 4 months, much earlier than the 9 to 12 months typically required after ligament reconstruction. Many athletes, such as high school baseball players or aging veteran professional baseball players, do not have the luxury of 12 months for recovery. Therefore, this select group of patients clearly has a limited window of opportunity to return to play. In fact, these patients might be ideal candidates for PRP injections for UCL injuries. Return-to-play rates, however, differed significantly among professional players and nonprofessional players. The difference may be attributable to professional players’ conditioning, quality of physical therapy, extrinsic motivation, and other intangible factors. Four (67%) of our 6 professional baseball players returned to professional play after injection, whereas only 36% of college players and 17% of high school players had excellent outcomes.

Limitations

The present study had several weaknesses, several of which are inherent to PRP studies conducted so far. It was not a prospective, randomized controlled trial. It is important to note that PRP treatment in diseased tissue may have some drawbacks, as its success depends on the ability of healing tissue to use concentrated growth factors and cytokines to proliferate.35 Thus, a chronically injured ligament with depleted active cells may have a diminished response to PRP. Another limitation of this study is that we evaluated outcomes based on return to play using the Conway Scale, which is well reported but not validated. Despite the potential weaknesses of this outcome scale, it has become the benchmark for measuring the success of outcomes of UCL reconstruction. Furthermore, we did not measure patients’ satisfaction with the treatment. Players who could not return to their preinjury level of play may have considered the treatment a failure regardless of their ability to continue throwing. Last, MRI was not repeated to document ligament healing. We did not routinely perform a second MRI because we thought it would not affect treatment. Several series have found a high incidence of abnormal signal in baseball players’ UCLs. In this group of patients, the most important outcome is return to previous level of competition.

This study raised several questions. Is one PRP brand better than another? Should more than 1 injection be given? What is the ideal postinjection protocol? Clearly, larger, prospective, randomized controlled studies are needed to truly elucidate the potential role of PRP in the treatment algorithm for UCL injury. Nevertheless, in certain cases in which traditional conservative measures have failed and patients do not have the luxury of rehabilitating for 9 to 12 months after surgery, PRP may be a viable treatment option.

Conclusion

In this study, use of PRP in the treatment of UCL insufficiency produced outcomes much better than earlier reported outcomes of conservative treatment of these injuries. PRP injections may be particularly beneficial in young athletes who have sustained acute damage to an isolated part of the ligament and in athletes unwilling or unable to undergo the extended rehabilitation required after surgical reconstruction of the ligament.

For overhead athletes, elbow ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) insufficiency is a potential career-ending injury. Baseball players with UCL insufficiency typically complain of medial-sided elbow pain that affects their ability to throw. Loss of velocity, loss of control, difficulty warming up, and pain while throwing are all symptoms of UCL injury.

Classically, nonoperative treatment of UCL injuries involves activity modification, use of anti-inflammatory medication, and a structured physical therapy program. Asymptomatic players can return to throwing after a structured interval throwing program. Rettig and colleagues1 found a 42% rate of success in conservatively treating UCL injuries in throwing athletes. UCL reconstruction is reserved for players with complete tears of the UCL or with partial tears after failed conservative treatment. Several techniques have been used to reconstruct the ligament, but successful outcomes depend on a long rehabilitation process. According to most published series, 85% to 90% of athletes who had UCL reconstruction returned to their previous level of play, but it took, on average, 9 to 12 months.2,3 This prolonged recovery period is one reason that some older professional baseball players, as well as casual high school and college players, elect to forgo surgery.

Over the past few years, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has garnered attention as a bridge between conservative treatment and surgery. PRP refers to a sample of autologous blood that contains a platelet concentration higher than baseline levels. This sample often has a 3 to 5 times increase in growth factor concentration.4-6 Initial studies focused on its ability to successfully treat lateral epicondylitis.7-9 More recent clinical work has shown that PRP can potentially enhance healing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,10-14 rotator cuff repair,15-17 and subacromial decompression.11,18-23 If PRP could be used to successfully treat UCL insufficiency that is refractory to conservative treatment, then year-long recovery periods could be avoided. This could potentially prolong certain athletes’ careers or, at the very least, allow them to return to play much sooner. In the present case series, we hypothesized that PRP injections could be used to successfully treat partial UCL tears in high-level throwing athletes, obviating the need for surgery and its associated prolonged recovery period.

Materials and Methods

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this retrospective study of 44 baseball players treated with PRP injections for partial-thickness UCL tears.

Patients provided written informed consent. They were diagnosed with UCL insufficiency by physical examination, and findings were confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). After diagnosis, all throwers underwent a trial of conservative treatment that included rest, activity modification, use of anti-inflammatory medication, and physical therapy followed by an attempt to return to throwing using an interval throwing program.

Study inclusion criteria were physical examinations and MRI results consistent with UCL insufficiency, and failure of the conservative treatment plan described.

Patients were injected using the Autologous Conditioned Plasma system (Arthrex). PRP solutions were prepared according to manufacturer guidelines. After the elbow was prepared sterilely, the UCL was injected at the location of the tear. Typically, 3 mL of PRP was injected into the elbow. Sixteen patients had 1 injection, 6 had 2, and 22 had 3. Repeat injections were considered for recalcitrant pain after 3 weeks.

After injection, patients used acetaminophen and ice for pain control. Anti-inflammatory medications were avoided for a minimum of 2 weeks after injection. Typical postinjection therapy protocol consisted of rest followed by progressive stretching and strengthening for about 4 to 6 weeks before the start of an interval throwing program. Although there is no well-defined postinjection recovery protocol, as a general rule rest was prescribed for the first 2 weeks, followed by a progressive stretching and strengthening program for the next month. Patients who were asymptomatic subjectively and clinically—negative moving valgus stress test, negative milking maneuver, no pain with valgus stress—were started on an interval throwing program.

Final follow-up involved a physical examination. Results were classified according to a modified version of the Conway Scale12,24-26: excellent (return to preinjury level of competition or performance), good (return to play at a lower level of competition or performance or, specifically for baseball players, ability to throw in daily batting practice), fair (able to play recreationally), and poor (unable to return to previous sport at any level).

By final follow-up, all patients had completed their postoperative rehabilitation protocol, and all had at least tried to return to their previous activities. No patients were lost to follow-up.

Results

Of the 44 baseball players, 6 were professional, 14 were in college, and 24 were in high school. There were 36 pitchers and 8 position players. Mean age was 17.3 years (range, 16-28 years). All patients were available for follow-up after injection (mean, 11 months). Fifteen of the 44 players had an excellent outcome (34%), 17 had a good outcome, 2 had a fair outcome, and 10 had a poor outcome. After injection, 4 (67%) of the 6 professional baseball players returned to professional play. Five (36%) of the 14 college players had an excellent outcome, and 4 (17%) of the 24 high school players had an excellent outcome. Of the 8 position players, 4 had an excellent outcome, 3 had a good outcome, and 1 had a poor outcome.

Before treatment, all patients had medial-sided elbow pain over the UCL inhibiting their ability to throw. Mean duration of symptoms before injection was 8.8 months (range, 1-36 months). There was no correlation between symptom duration and any outcome measure. On MRI, 29 patients showed partial tears: 22 proximally based and 7 distally based. The other 15 patients had diffuse signal without partial tear. All 7 patients with distally based partial tears and 3 of the patients with proximally based partial tears had a poor outcome. Overall, there were 6 excellent, 7 good, and 2 fair outcomes in the partial-tear group. In the patients with diffuse signal without partial tear, there were 9 excellent and 10 good outcomes.

Mean time from injection to return to throwing was 5 weeks, and mean time to return to competition was 12 weeks (range, 5-24 weeks). The 1 player who returned at 5 weeks was a professional relief pitcher whose team was in the playoffs. He has now pitched for an additional 2 baseball seasons without elbow difficulty.

There were no injection-related complications.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report documenting successful PRP treatment of UCL insufficiency. In this study, 73% of players who had failed a course of conservative treatment had good to excellent outcomes with PRP injection.

Data on successful nonoperative treatment of UCL injuries are limited. Rettig and colleagues1 treated 31 throwing athletes’ UCL injuries with a supervised rehabilitation program. Treatment included rest, use of anti-inflammatory medication, progressive strengthening, and an interval throwing program. Only 41% of the athletes returned to their previous level of play, and it took, on average, 24.5 weeks. There was no significant difference in age or in duration or acuity of symptoms between those who returned to play and those whose conservative treatment failed.

Surgical reconstruction of UCL injuries has been very successful, with upward of 90% of athletes returning to previous level of play.3,27The procedure, however, is not without associated complications, including retear of the ligament, stiffness, ulnar nerve injury, and fracture.27-29 In addition, even when successful, the procedure requires that athletes take 9 to 12 months to recover before returning to competition at their previous level.

Savoie and colleagues,30 in their recent study on UCL repairs, highlighted an important fact that is often overlooked when reviewing the literature on UCL tears. Most of the literature on these injuries focuses on college and professional baseball players in whom ligament damage is often extensive, precluding repair. In contrast to prior reports, Savoie and colleagues30 found excellent results in 93% of their young athletes who underwent UCL repair. It is possible that their results can be attributed to the fact that many of their athletes had tears isolated to one area of the ligament, as opposed to generalized ligament incompetence. Our improved results vis-à-vis other reports on conservative management may be attributable to the same phenomenon.

PRP has garnered much attention in the literature and media because of its potential to enhance healing of tendons and ligaments; in some cases, it can obviate the need for surgery. After failure of other nonoperative measures in 15 patients with elbow epicondylitis, Mishra and Pavelko8 treated each patient with a single PRP injection. They prepared the PRP using the GPS III system (Biomet). At final follow-up, 93% improvement was seen. Clearly, their experiment had design flaws: It was nonblinded, and 3 of the 5 patients in the control group treated with bupivacaine injection withdrew from the experiment. Despite its shortcomings, their study became the impetus for several other studies.

A larger, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial comparing PRP and cortisone injections for lateral epicondylitis in 100 patients is under way, and preliminary results have been published.9 A minimum of 6 months after injection, patients who received PRP showed more improvement in visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores and Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire scores. In another large, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial, patients with chronic lateral epicondylitis had significant improvements in VAS pain scores and DASH scores relative to patients injected with corticosteroids with a 2-year follow-up.31 Similarly, Thanasas and colleagues32 found significantly reduced VAS pain scores in patients injected with PRP versus autologous whole blood. Another study demonstrated improved tendon morphology using ultrasound imaging 6 months after PRP injection.33

Contrary to these positive results, Krogh and colleagues34 found that a single injection of PRP or glucocorticoid was not significantly superior to a saline injection for reducing pain and disability over a 3-month period in patients with lateral epicondylitis. Their study, however, had major flaws. Its original design called for a 12-month follow-up, but there was massive dropout in all 3 treatment arms, necessitating reporting of only 3-month data. In addition, 60% of the patients in the glucocorticoid group were not naïve to this treatment, so definitive conclusions about the efficacy of glucocorticoids could not be made.

In the present study, we successfully treated partial ligament tears with PRP injections. Sixty-seven percent of our baseball players returned to play at a mean of 4 months, much earlier than the 9 to 12 months typically required after ligament reconstruction. Many athletes, such as high school baseball players or aging veteran professional baseball players, do not have the luxury of 12 months for recovery. Therefore, this select group of patients clearly has a limited window of opportunity to return to play. In fact, these patients might be ideal candidates for PRP injections for UCL injuries. Return-to-play rates, however, differed significantly among professional players and nonprofessional players. The difference may be attributable to professional players’ conditioning, quality of physical therapy, extrinsic motivation, and other intangible factors. Four (67%) of our 6 professional baseball players returned to professional play after injection, whereas only 36% of college players and 17% of high school players had excellent outcomes.

Limitations

The present study had several weaknesses, several of which are inherent to PRP studies conducted so far. It was not a prospective, randomized controlled trial. It is important to note that PRP treatment in diseased tissue may have some drawbacks, as its success depends on the ability of healing tissue to use concentrated growth factors and cytokines to proliferate.35 Thus, a chronically injured ligament with depleted active cells may have a diminished response to PRP. Another limitation of this study is that we evaluated outcomes based on return to play using the Conway Scale, which is well reported but not validated. Despite the potential weaknesses of this outcome scale, it has become the benchmark for measuring the success of outcomes of UCL reconstruction. Furthermore, we did not measure patients’ satisfaction with the treatment. Players who could not return to their preinjury level of play may have considered the treatment a failure regardless of their ability to continue throwing. Last, MRI was not repeated to document ligament healing. We did not routinely perform a second MRI because we thought it would not affect treatment. Several series have found a high incidence of abnormal signal in baseball players’ UCLs. In this group of patients, the most important outcome is return to previous level of competition.

This study raised several questions. Is one PRP brand better than another? Should more than 1 injection be given? What is the ideal postinjection protocol? Clearly, larger, prospective, randomized controlled studies are needed to truly elucidate the potential role of PRP in the treatment algorithm for UCL injury. Nevertheless, in certain cases in which traditional conservative measures have failed and patients do not have the luxury of rehabilitating for 9 to 12 months after surgery, PRP may be a viable treatment option.

Conclusion

In this study, use of PRP in the treatment of UCL insufficiency produced outcomes much better than earlier reported outcomes of conservative treatment of these injuries. PRP injections may be particularly beneficial in young athletes who have sustained acute damage to an isolated part of the ligament and in athletes unwilling or unable to undergo the extended rehabilitation required after surgical reconstruction of the ligament.

1. Rettig AC, Sherrill C, Snead DS, Mendler JC, Mieling P. Nonoperative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries in throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(1):15-17.

2. Eygendaal D, Rahussen FT, Diercks RL. Biomechanics of the elbow joint in tennis players and relation to pathology. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(11):820-823.

3. Bowers AL, Dines JS, Dines DM, Altchek DW. Elbow medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: clinical relevance and the docking technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):110-117.

5. Kibler WB. Biomechanical analysis of the shoulder during tennis activities. Clin Sports Med. 1995;14(1):79-85.

5. Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(4):489-496.

6. Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what is PRP and what is not PRP? Implant Dent. 2001;10(4):225-228.

7. Elliott B, Fleisig G, Nicholls R, Escamilia R. Technique effects on upper limb loading in the tennis serve. J Sci Med Sport. 2003;6(1):76-87.

8. Mishra A, Pavelko T. Treatment of chronic elbow tendinosis with buffered platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(11):1774-1778.

9. Mishra A, Woodall J Jr, Vieira A. Treatment of tendon and muscle using platelet-rich plasma. Clin Sports Med. 2009;28(1):113-125.

10. Kovacs MS. Applied physiology of tennis performance. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(5):381-386.

11. Xie X, Wu H, Zhao S, Xie G, Huangfu X, Zhao J. The effect of platelet-rich plasma on patterns of gene expression in a dog model of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Surg Res. 2013;180(1):80-88.

12. Pluim BM, Staal JB, Windler GE, Jayanthi N. Tennis injuries: occurrence, aetiology, and prevention. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(5):415-423.

13. Xie X, Zhao S, Wu H, et al. Platelet-rich plasma enhances autograft revascularization and reinnervation in a dog model of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Surg Res. 2013;183(1):214-222.

14. Lopez-Vidriero E, Goulding KA, Simon DA, Sanchez M, Johnson DH. The use of platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopy and sports medicine: optimizing the healing environment. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(2):269-278.

15. Jo CH, Shin JS, Shin WH, Lee SY, Yoon KS, Shin S. Platelet-rich plasma for arthroscopic repair of medium to large rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(9):2102-2110.

16. Jo CH, Shin JS, Lee YG, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for arthroscopic repair of large to massive rotator cuff tears: a randomized, single-blinded, parallel-group trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2240-2248.

17. Randelli P, Arrigoni P, Ragone V, Aliprandi A, Cabitza P. Platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective RCT study, 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):518-528.

18. Randelli P, Arrigoni P, Ragone V, Aliprandi A, Cabitza P. Platelet rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective RCT study, 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):518-528.

19. Barber FA, Hrnack SA, Snyder SJ, Hapa O. Rotator cuff repair healing influenced by platelet-rich plasma construct augmentation. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(8):1029-1035.

20. Jo CH, Kim JE, Yoon KS, et al. Does platelet-rich plasma accelerate recovery after rotator cuff repair? A prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2082-2090.

21. Jo CH, Kim JE, Yoon KS, Shin S. Platelet-rich plasma stimulates cell proliferation and enhances matrix gene expression and synthesis in tenocytes from human rotator cuff tendons with degenerative tears. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1035-1045.

22. Chahal J, Van Thiel GS, Mall N, et al. The role of platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a systematic review with quantitative synthesis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1718-1727.

23. Mei-Dan O, Carmont MR. The role of platelet-rich plasma in rotator cuff repair. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19(3):244-250.

24. Dines JS, ElAttrache NS, Conway JE, Smith W, Ahmad CS. Clinical outcomes of the DANE TJ technique to treat ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(12):2039-2044.

25. Hutchinson MR, Laprade RF, Burnett QM 2nd, Moss R, Terpstra J. Injury surveillance at the USTA boys’ tennis championships: a 6-yr study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(6):826-830.

26. Winge S, Jørgensen U, Nielsen A. Epidemiology of injuries in Danish championship tennis. Int J Sports Med. 1989;10(5):368-371.

27. Safran MR, Hutchinson MR, Moss R, Albrandt J. A comparison of injuries in elite boys and girls tennis players. Paper presented at: 9th Annual Meeting of the Society of Tennis Medicine and Science; March 1999; Indian Wells, CA.

28. Cain EL, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, et al. Outcome of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow in 1281 athletes: results in 743 athletes with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2426-2434.

29. Dines JS, Yocum LA, Frank JB, ElAttrache NS, Gambardella RA, Jobe FW. Revision surgery for failed elbow medial collateral ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1061-1065.

30. Savoie FH, Trenhaile SW, Roberts J, Field LD, Ramsey JR. Primary repair of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in young athletes: a case series of injuries to the proximal and distal ends of the ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1066-1072.

31. Gosens T, Peerbooms JC, van Laar W, Oudsten den BL. Ongoing positive effect of platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection in lateral epicondylitis: a double-blind randomized controlled trial with 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1200-1208.

32. Thanasas C, Papadimitriou G, Charalambidis C, Paraskevopoulos I, Papanikolaou A. Platelet-rich plasma versus autologous whole blood for the treatment of chronic lateral elbow epicondylitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2130-2134.

33. Chaudhury S, La Lama de M, Adler RS, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: sonographic assessment of tendon morphology and vascularity (pilot study). Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(1):91-97.

34. Krogh TP, Fredberg U, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Christensen R, Jensen P, Ellingsen T. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with platelet-rich plasma, glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):625-635.

35. Anz AW, Hackel JG, Nilssen EC, Andrews JR. Application of biologics in the treatment of the rotator cuff, meniscus, cartilage, and osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(2):68-79.

1. Rettig AC, Sherrill C, Snead DS, Mendler JC, Mieling P. Nonoperative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries in throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(1):15-17.

2. Eygendaal D, Rahussen FT, Diercks RL. Biomechanics of the elbow joint in tennis players and relation to pathology. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(11):820-823.

3. Bowers AL, Dines JS, Dines DM, Altchek DW. Elbow medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: clinical relevance and the docking technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):110-117.

5. Kibler WB. Biomechanical analysis of the shoulder during tennis activities. Clin Sports Med. 1995;14(1):79-85.

5. Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(4):489-496.

6. Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what is PRP and what is not PRP? Implant Dent. 2001;10(4):225-228.

7. Elliott B, Fleisig G, Nicholls R, Escamilia R. Technique effects on upper limb loading in the tennis serve. J Sci Med Sport. 2003;6(1):76-87.

8. Mishra A, Pavelko T. Treatment of chronic elbow tendinosis with buffered platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(11):1774-1778.

9. Mishra A, Woodall J Jr, Vieira A. Treatment of tendon and muscle using platelet-rich plasma. Clin Sports Med. 2009;28(1):113-125.

10. Kovacs MS. Applied physiology of tennis performance. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(5):381-386.

11. Xie X, Wu H, Zhao S, Xie G, Huangfu X, Zhao J. The effect of platelet-rich plasma on patterns of gene expression in a dog model of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Surg Res. 2013;180(1):80-88.

12. Pluim BM, Staal JB, Windler GE, Jayanthi N. Tennis injuries: occurrence, aetiology, and prevention. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(5):415-423.

13. Xie X, Zhao S, Wu H, et al. Platelet-rich plasma enhances autograft revascularization and reinnervation in a dog model of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Surg Res. 2013;183(1):214-222.

14. Lopez-Vidriero E, Goulding KA, Simon DA, Sanchez M, Johnson DH. The use of platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopy and sports medicine: optimizing the healing environment. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(2):269-278.

15. Jo CH, Shin JS, Shin WH, Lee SY, Yoon KS, Shin S. Platelet-rich plasma for arthroscopic repair of medium to large rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(9):2102-2110.

16. Jo CH, Shin JS, Lee YG, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for arthroscopic repair of large to massive rotator cuff tears: a randomized, single-blinded, parallel-group trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2240-2248.

17. Randelli P, Arrigoni P, Ragone V, Aliprandi A, Cabitza P. Platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective RCT study, 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):518-528.

18. Randelli P, Arrigoni P, Ragone V, Aliprandi A, Cabitza P. Platelet rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective RCT study, 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):518-528.

19. Barber FA, Hrnack SA, Snyder SJ, Hapa O. Rotator cuff repair healing influenced by platelet-rich plasma construct augmentation. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(8):1029-1035.

20. Jo CH, Kim JE, Yoon KS, et al. Does platelet-rich plasma accelerate recovery after rotator cuff repair? A prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2082-2090.

21. Jo CH, Kim JE, Yoon KS, Shin S. Platelet-rich plasma stimulates cell proliferation and enhances matrix gene expression and synthesis in tenocytes from human rotator cuff tendons with degenerative tears. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1035-1045.

22. Chahal J, Van Thiel GS, Mall N, et al. The role of platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a systematic review with quantitative synthesis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1718-1727.

23. Mei-Dan O, Carmont MR. The role of platelet-rich plasma in rotator cuff repair. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19(3):244-250.

24. Dines JS, ElAttrache NS, Conway JE, Smith W, Ahmad CS. Clinical outcomes of the DANE TJ technique to treat ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(12):2039-2044.

25. Hutchinson MR, Laprade RF, Burnett QM 2nd, Moss R, Terpstra J. Injury surveillance at the USTA boys’ tennis championships: a 6-yr study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(6):826-830.

26. Winge S, Jørgensen U, Nielsen A. Epidemiology of injuries in Danish championship tennis. Int J Sports Med. 1989;10(5):368-371.

27. Safran MR, Hutchinson MR, Moss R, Albrandt J. A comparison of injuries in elite boys and girls tennis players. Paper presented at: 9th Annual Meeting of the Society of Tennis Medicine and Science; March 1999; Indian Wells, CA.

28. Cain EL, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, et al. Outcome of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow in 1281 athletes: results in 743 athletes with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2426-2434.

29. Dines JS, Yocum LA, Frank JB, ElAttrache NS, Gambardella RA, Jobe FW. Revision surgery for failed elbow medial collateral ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1061-1065.

30. Savoie FH, Trenhaile SW, Roberts J, Field LD, Ramsey JR. Primary repair of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in young athletes: a case series of injuries to the proximal and distal ends of the ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1066-1072.

31. Gosens T, Peerbooms JC, van Laar W, Oudsten den BL. Ongoing positive effect of platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection in lateral epicondylitis: a double-blind randomized controlled trial with 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1200-1208.

32. Thanasas C, Papadimitriou G, Charalambidis C, Paraskevopoulos I, Papanikolaou A. Platelet-rich plasma versus autologous whole blood for the treatment of chronic lateral elbow epicondylitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2130-2134.

33. Chaudhury S, La Lama de M, Adler RS, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: sonographic assessment of tendon morphology and vascularity (pilot study). Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(1):91-97.

34. Krogh TP, Fredberg U, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Christensen R, Jensen P, Ellingsen T. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with platelet-rich plasma, glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):625-635.

35. Anz AW, Hackel JG, Nilssen EC, Andrews JR. Application of biologics in the treatment of the rotator cuff, meniscus, cartilage, and osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(2):68-79.

Shoulder Instability Management: A Survey of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons

Despite an abundance of peer-reviewed resources, there is wide variation in the surgical management of shoulder instability.1,2 Current American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) clinical practice guidelines regarding the shoulder address only generalized shoulder pain, glenohumeral osteoarthritis, and rotator cuff injuries,3,4 and treatment algorithms focus on conservative treatment, rather than surgical recommendations.4-7

Shoulder instability most commonly results from 1 or more of 4 common lesions (capsular laxity, glenoid bone loss, humeral bone loss, and capsulolabral insufficiency).8 While it is a relatively common condition that represents 1% to 2% of all athletic injuries,9,10 little consensus exists about surgical indications, ideal treatment algorithms, or optimal operative technique. This is a critical issue because more than 50% of patients with glenohumeral instability will undergo surgical intervention.11 Chahal and associates6 surveyed 44 shoulder experts and reported strong consensus about diagnosis, but little agreement regarding surgical management. Owens and colleagues1 have also evaluated current trends for surgical treatment of this pathology. Randelli and associates5 attempted to categorize operative management based upon case-specific shoulder scenarios through online surveys. Their survey, however, covered a broad range of shoulder injuries rather than instability in particular. In this study, we assess trends for surgical management of glenohumeral instability in a case-based survey of shoulder experts.

Materials and Methods

Survey Information

An online survey (Survey Monkey) of 417 active members of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) was administered on May 1, 2014. Respondents were blinded to the institution and co-investigators conducting the survey. The survey link was distributed via email because it has been shown to be a more efficacious conduit than standard postal mail.12 The case-based, 25-question survey (Appendix) was designed to assess respondents’ selection of surgical intervention. Section 1 determined member demographics, including fellowship training, arthroscopy experience, and years of practice. Section 2 involved the presentation of 5 case scenarios. For each case, respondents were asked to identify the optimal surgical procedure in both primary and revision settings. Section 3 posed several general questions regarding shoulder-instability management.

Statistical Analysis

Data were stored using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft) and analyzed using SAS Software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc.). Demographic survey responses were reported using descriptive statistics. Responses to clinical survey questions were reported using frequencies and percentages. To identify when a majority consensus was achieved for a given question, responses were flagged as reaching consensus when more than 50% of participants gave the same response.13In the event that only 2 response options were available, reaching consensus required 67% of respondents to choose a single answer (since, by default, a consensus would be reached with only 2 response options). Because this was an analysis of all respondents, an a priori power calculation was not performed. Associations between training and practice demographics and responses to clinical questions were investigated using chi-square analyses. All comparative analyses were two-tailed and used P = .05 as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Demographics

One hundred and twenty-five (29.9%) ASES members responded to the survey. Of the respondents, 71.2% reported at least 15 years of experience, and 71% performed more than 150 shoulder cases annually. Surgeons came from academic institutions (41.6%), private practice (24.8%), or mixed (33.6%). The majority of respondents were fellowship-trained in shoulder/elbow surgery (52.8%), while fewer had completed a sports-medicine fellowship (24.0%). For arthroscopic procedures, responses were nearly divided between those who preferred beach-chair positioning (47.2%) and those who preferred the lateral decubitus position (46.4%). The majority (70.4%) of respondents practiced in the United States and with a relatively even distribution among states and region. The remaining 29.6% of those surveyed practiced abroad.

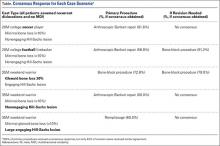

Degree of Consensus Responses and Cases

Of the 25 survey questions, 6 questions were omitted from consensus calculations because these were designed for demographic categorization rather than professional opinion (questions 1-5, 8). Thirteen of the remaining 19 questions (68%) reached consensus response. All clinical case scenarios (5 of 5) reached consensus for selection of technique for the primary procedure; however, only 40% (2 of 5) of cases had a consensus in the revision setting.

In case 1, a young soccer player (noncontact athlete) with negligible bone loss, arthroscopic Bankart repair was recommended by 81.6% of respondents. In the event of revision surgery, only 22.4% recommended arthroscopic Bankart repair, and the remainder split between open Bankart repair with possible capsular shift (36%) or Latarjet procedure (32.8%).

In case 2, a college American football player (contact athlete) with negligible bone loss, arthroscopic Bankart repair was recommended by 56.8%. In the event of revision surgery, a majority of members (51.2%) suggested a Latarjet procedure.

In case 3, the weekend warrior with significant bone loss, most respondents recommended a Latarjet procedure for both primary (72.8%) and revision surgery (79.0%).

In case 4, a weekend warrior with multidirectional instability, 60% of respondents suggested arthroscopic Bankart repair, 21.6% recommended rotator interval closure, and 10.4% chose a capsular shift. As a revision procedure, there was less agreement, with a split between open Bankart repair (39.2%) and capsular shift only (39.2%).

In case 5, the weekend warrior with large engaging Hill-Sachs lesions, 60% of respondent selected a remplissage procedure. If revision was required, a Latarjet procedure was the choice of 48.8% of respondents (Table).

General Questions

For contact athletes, most respondents (87.2%) would allow return to play in the same season and recommended surgery after the end of the season. After surgical intervention, 56.8% prescribed 4 weeks of immobilization. When counseling a return to contact sports, 51.2% recommended waiting for 4 to 6 months.

The ASES members were divided on conservative management of instability injuries. Responses included immobilization in internal rotation (39.2%), no immobilization (39.2%), and external-rotation bracing (21.6%).

Finally, members thought the most important factor in choosing surgical technique was the patient’s pathology, then age; the least influential criteria was the patient’s sports participation.

Analysis of Training Demographics and Surgical Technique Preferences

Chi-square analyses demonstrated that respondents who completed a sports fellowship were more likely to do at least 50% of cases arthroscopically (odds ratio [OR], 15.3; P < .001) and were more likely to use the lateral decubitus position (OR, 2.8; P < .021). Furthermore, American respondents had a higher likelihood of having completed either a sports fellowship (OR, 12.8; P < .001) or a shoulder/elbow fellowship (OR, 4.6; P = .002) when compared with foreign respondents.

Discussion

In the absence of formal clinical practice guidelines, most surgeons formulate treatment strategy based upon a combination of experience and peer-reviewed evidence. The cohort analyzed in the current study was highly experienced, with more than 70% performing 150 shoulder cases annually and having more than 15 years of experience. We found a consensus response in 68% of questions and all primary surgical techniques for our shoulder instability scenarios. While expert consensus reported here is not equivalent to evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, it does provide important information to consider when treating anterior shoulder instability.

Specific responses to our case scenarios invite further reflection. Considering young (both noncontact and contact) athletes without bony pathology (cases 1 and 2, respectively), the ASES surgeons recommended arthroscopic Bankart repair for both. Randelli and associates5 found 71% of survey respondents recommended arthroscopic Bankart repair in a similar setting. It is interesting to note that consensus persisted regardless of the sport in which they engaged. Contact athletes have the highest rates of dislocation (up to 7 times higher incidence) compared with the general population.14 In addition, they have a higher recurrence rate after surgery.15 It should be noted, however, that although both cases reached consensus, the percentage of experts who recommended an arthroscopic procedure fell from 82% in the noncontact athlete to 57% in the contact athlete. This concurs with a recent review by Harris and Romeo,16 who recommended similar treatments for athletes without bony defects. In an older patient population with recurrent instability (case 3), responses varied more widely but still reached a consensus on primary surgical techniques. Respondents agreed that, even for patients with multidirectional instability, initial management should consist of arthroscopic capsulolabral repair. Overall, the agreement for arthroscopy for cases 1 through 3 mimics recent US practice patterns, showing 90% of stabilizations are being performed arthroscopically.17 Additionally, a recent meta-analysis by Harris and associates18 favored arthroscopic Bankart repair, showing no significant difference vs open stabilization even on long-term follow-up.

Glenoid bone loss is a difficult clinical scenario and that is reflected in this study’s findings. The literature suggests that arthroscopic Bankart repair, in this setting, is usually not sufficient and may result in a recurrence rate up to 75%, if bone loss greater than 20% is unaddressed.19 Our study supports this trend because ASES members recommended a Latarjet procedure when there is substantial bone loss.

While open Latarjet procedure was the consensus for dealing with glenoid bone loss, arthroscopic techniques were strongly favored for humeral head defects. This change in practice patterns results from the introduction of the arthroscopic remplissage technique.20 Two recent systemic reviews have supported this technique, reporting good functional outcomes for engaging Hill-Sachs lesions.21,22 Our study had similar agreement, with most respondents recommending remplissage for these patients.

This study found the lowest rates of expert consensus in the setting of revision surgery, likely caused, in part, by the paucity of available large cohort studies. This is a major void in the literature, and more studies are needed to help guide surgeons on the best techniques to deal with this difficult patient population.

Conservative bracing technique was 1 of the survey questions lacking a consensus response. Interestingly, 39% of members recommended no immobilization after an instability event. This contrasts with recent literature concerning the best position for bracing. We also found twice as many surgeons recommended internal rotation immobilization over external rotation. This is a subject of debate, with some studies stating improvement with external rotation immobilization,23 while other studies reported no difference.24 Overall, recommendations regarding type of immobilization are unclear, which will likely continue until larger studies can be performed.

The literature describing surgical trends in the treatment of shoulder instability is sparse and variable. With regard to other shoulder etiologies, only rotator cuff pathology has used expert consensus. Acevedo and colleagues13 reported agreement of ASES members surveyed regarding rotator cuff management. There was no consensus among surgeons in more than 50% of questions, despite AAOS published guidelines for rotator cuff treatment.25 Despite the lack of guidelines for our topic, we found a consensus among respondents with 68% of survey questions.

To date, only 2 studies of shoulder instability management have elicited the opinion of experts in shoulder surgery. Chahal and associates6 surveyed 42 members of ASES and JOINTS (Joined Orthopaedic Initiatives for National Trials of the Shoulder) Canada on shoulder instability cases and found substantial agreement on diagnosis but little consensus regarding surgical technique. This lack of agreement on procedures differs from our findings and may be related to their complicated case scenarios that generated a wide array of treatment recommendations. Randelli and colleagues5 surveyed more than 1000 European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery, and Arthroscopy members and reported similar agreement on arthroscopic Bankart repair in young male shoulder-dislocation patients, although no other instability scenarios were investigated. Our study is the first to report responses from expert shoulder surgeons on surgical-treatment strategies for an array of common shoulder instability pathologies.

This study had several limitations. First, while our study suffered from a low response rate (29.9%), it was similar to other published studies.5,13 Second, because the case series included in the survey attempted to capture the most common instability scenarios, they were limited in their scope and failed to address additional etiologies or pathologic permutations. We believe, however, that a more comprehensive survey would have resulted in respondent fatigue and lowered the response rate. It is unlikely that any survey could capture all variables that come into play during clinical decision-making, and we sought to evaluate the most common shoulder instability scenarios. Third, 30% of respondents were from outside the United States, where the Latarjet procedure is much more popular. While this was not a majority, Latarjet’s regional preference may have decreased the consensus response in some scenarios if only the United States was included. Finally, there is inherent bias in a respondent pool that is heavily weighted to shoulder-surgery experts (ASES members) and does not consider the responses of the general orthopedic surgery community as have other studies.7

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that expert shoulder surgeons often agreed on shoulder-treatment principles for anterior shoulder instability. In the setting of primary repair, arthroscopic Bankart repair was favored in the absence of bony pathology, regardless of age (20 to 35 years) or nature of sport (contact versus noncontact). Latarjet procedures were favored in the setting of glenoid bone loss, and remplissage for an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Less agreement was observed for revision stabilization. It should be noted that, while consensus was often reached for our cases, there was a wide distribution of technical considerations and surgical preferences even among those who are fellowship-trained and high-volume surgeons, and who can be considered experts in the field of shoulder surgery.

1. Owens BD, Harrast JJ, Hurwitz SR, Thompson TL, Wolf JM. Surgical trends in bankart repair: an analysis of data from the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery certification examination. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1865-1869.