Case Letter

From the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Berg is from the Perelman School of Medicine. Drs. Novoa, Stewart, Sobanko, Miller, and Rosenbach are from the Department of Dermatology.

Drs. Berg, Novoa, Stewart, Sobanko, and Miller report no conflict of interest. Dr. Rosenbach is a recipient of the Dermatology Foundation Medical Dermatology Career Development Award, which was used to support this study.

Correspondence: Misha Rosenbach, MD, Department of Dermatology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine, 2 Maloney Bldg, 3600 Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA 19104 (misha.rosenbach@uphs.upenn.edu).

Sarcoidosis is a chronic multisystem disease characterized by the formation of noncaseating granulomas in multiple organs, including the skin. An association between multisystem sarcoidosis and an increased risk for malignancy has been established. Dermatologists should be aware of the increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients with sarcoidosis. We report a series of 3 patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with new-onset cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Two patients were black women and 1 patient presented with lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis arising concurrently with SCCs in the same location, distinguishable only by biopsy. These cases highlight the association between sarcoidosis and an increased risk for SCC. Because dermatologists may be the primary clinicians caring for these patients, it is important that they remain aware of the increased risk for cutaneous malignancies and that they have a low threshold for biopsy of new and unusual skin lesions. Furthermore, 2 patients were black women, a population not commonly affected by skin cancer, which further exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in black patients. Although the precise mechanism for an increased risk for malignancy in these patients requires further investigation, chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation may play a role.

Practice Points

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek3 first described the link between pulmonary sarcoidosis and an increased incidence of malignancy in 1974. Since then, a number of studies have suggested that sarcoidosis may be associated with an increased risk for hematologic malignancy as well as an increased risk for cancers of the lungs, stomach, colon, liver, and skin.4,5 To date, few studies exist that examine the relationship between cutaneous sarcoidosis and malignancy.6

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

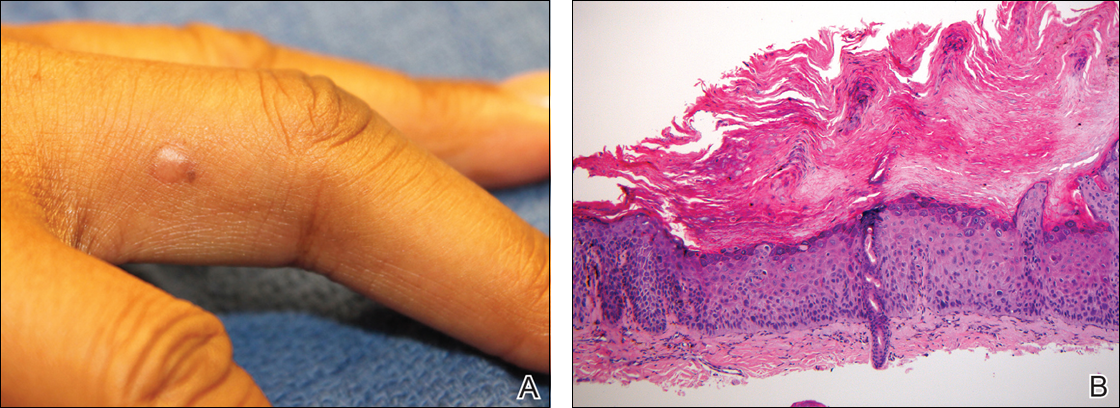

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Figure 1. Hyperpigmented, flesh-colored papule on the right third finger of a black woman with pulmonary and cutaneous sarcoidosis that was being maintained on adalimumab (A). Biopsy showed a full-thickness atypia of keratinocytes, with hyperchromatic nuclei, scattered necrotic cells, atypical mitoses, and overlying parakeratosis, consistent with squamous cell carcinoma in situ (B)(H&E, original magnification ×100).

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

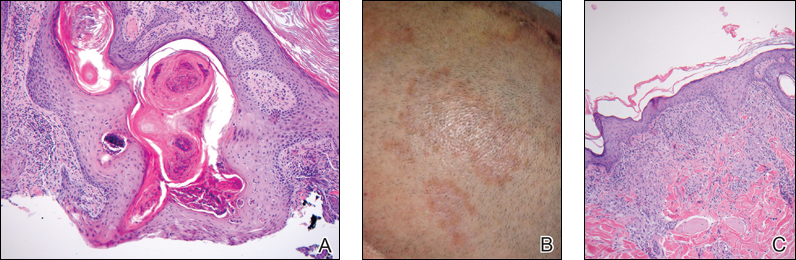

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Figure 2. A biopsy from a scalp lesion in a white man with pulmonary, cutaneous, and lymph node sarcoidosis who developed numerous nonmelanoma skin cancers showed epidermal hyperplasia and invagination with a keratin-filled core and mild keratinocyte atypia extending into the dermis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100). Slightly violaceous, annular, erythematous patches of cutaneous sarcoidosis were present on the scalp (B). Aggregates of histiocytes with giant cell formation and sparse lymphocytic inflammation consistent with sarcoidosis also were noted on biopsy (C)(H&E, original magnification ×100).

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an acquired, autoimmune, subepidermal blistering disorder. A possible paraneoplastic association has been suggested;...

The term isotopic response refers to the appearance of a new skin disease at the site of another unrelated and already healed skin disorder. Often...