In 2010, two separate reports of cutaneous vasculitic/vasculopathic eruptions in patients with recent exposure to levamisole-contaminated cocaine (LCC) were published in the literature.1,2 Since then, additional reports have been published.3-6 Retiform purpura associated with cocaine use appears to be a similar condition, perhaps lying at one end of the spectrum of LCC-induced cutaneous vascular disease.7,8 Although some patients have been described as having nausea and vomiting,8,9 including one with a sudden drop in hemoglobin to 5.8 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL),10 there are no known reported cases of LCC and levamisole-induced vasculopathy in organ systems other than the skin. Herein, we report the case of a patient with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV) demonstrating endoscopic evidence of gastric hemorrhage with features similar to those involving the skin.

Case Report

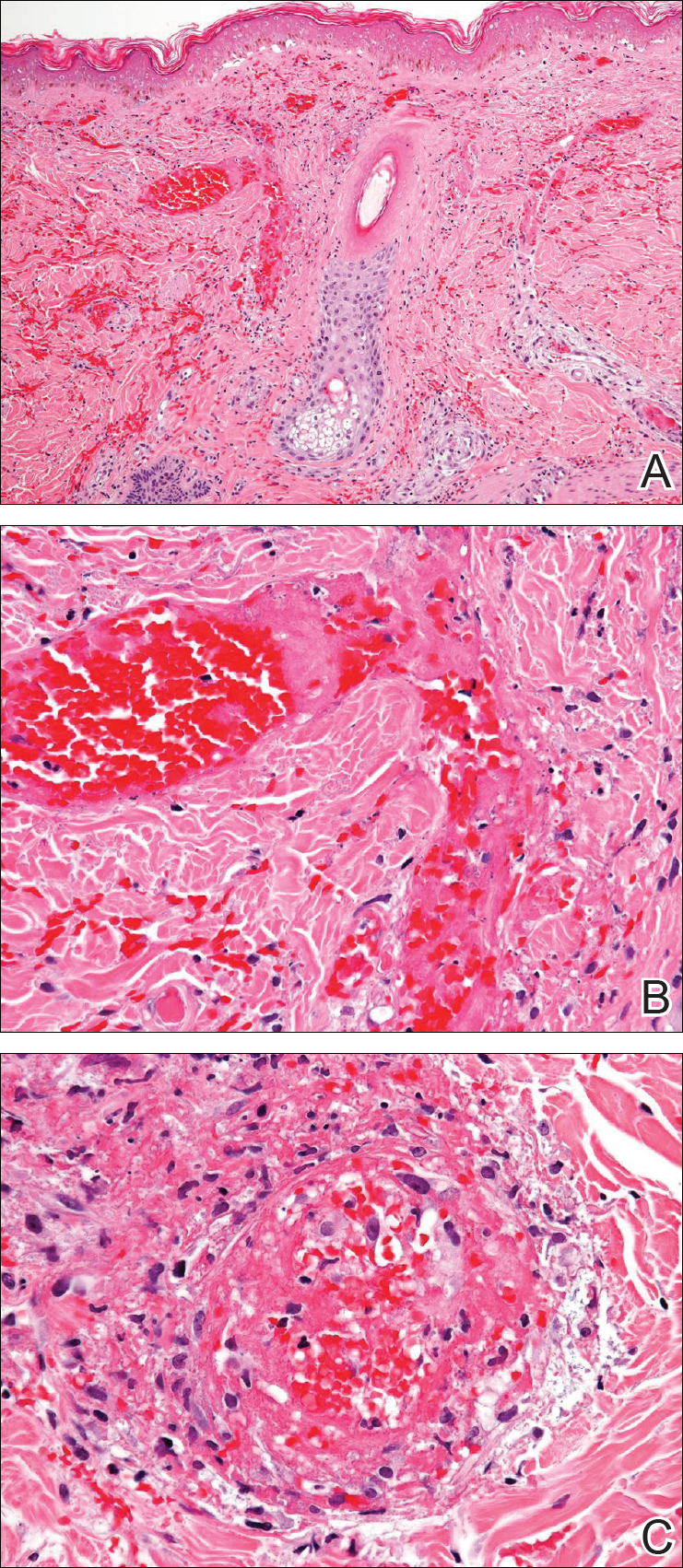

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C, intravenous drug abuse, and bipolar disorder presented to the emergency department with painful necrotic lesions on the head, neck, arms, and legs of several days’ duration. Approximately 1 year prior she had been admitted to the hospital with similar lesions, with eventual partial necrosis of the left earlobe. The patient reported she had last used crack cocaine 3 days prior to the development of the lesions. A urine drug screen was positive for lorazepam, alprazolam, buprenorphine, methadone, tetrahydrocannabinol, and cocaine. She also reported abdominal pain and gastric reflux of recent onset but denied any history of gastrointestinal tract disease. During the previous admission, the patient demonstrated antinuclear antibodies at a titer of greater than 1:160 (normal, <1:40) in a smooth pattern as well as positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) and cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA) and positive cryoglobulins. Physical examination yielded purpuric and hemorrhagic patches and plaques on the nose, bilateral ears (Figure 1A), face (Figure 1B), arms, and legs. Older lesions exhibited evidence of evolving erosion and ulceration. A biopsy of a lesion on the right arm was obtained, demonstrating extensive epidermal necrosis, hemorrhage, fibrin thrombi within dermal blood vessels, fibrinoid mural necrosis, perivascular neutrophils, and leukocytoclasis (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with LIV caused by exposure to LCC. A complete blood cell count was unremarkable. She was started on pain management and was given prednisone to treat the cutaneous eruption. Because of continued reports of epigastric pain and discomfort on swallowing, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed. Numerous esophageal erosions and gastric submucosal hemorrhages similar to those on the skin were noted (Figure 3). Pathology taken at the time of the endoscopy demonstrated mucosal erosions, but an evaluation for vascular insult was not possible, as submucosal tissue was not obtained. As the skin lesions began to heal, the gastric symptoms gradually subsided, and the patient was released from the hospital after 7 days.

Figure 2. Histologic features of a biopsy from a lesion on the patient’s right arm revealed epidermal necrosis with diffuse dermal hemorrhage and vessel wall breakdown (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Dilated and congested blood vessels were noted with hemorrhage and minimal inflammation typical of the vasculopathic aspect of this disease (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Blood vessels with fibrinoid necrosis of the wall and surrounding neutrophils with nuclear dust consistent with the vasculitic features of levamisole-induced vasculopathy also was seen (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200).