User login

Mobile Enlarging Scalp Nodule

The Diagnosis: Hybrid Schwannoma-Perineurioma

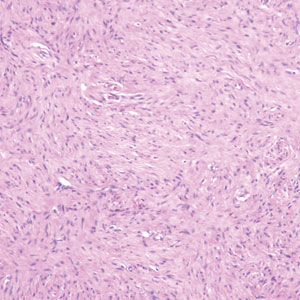

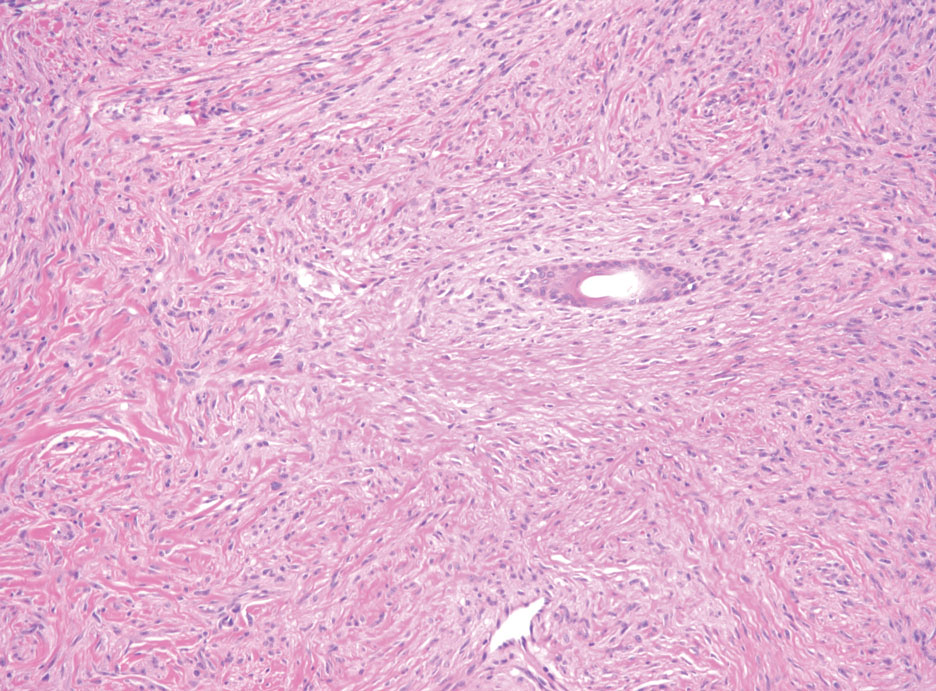

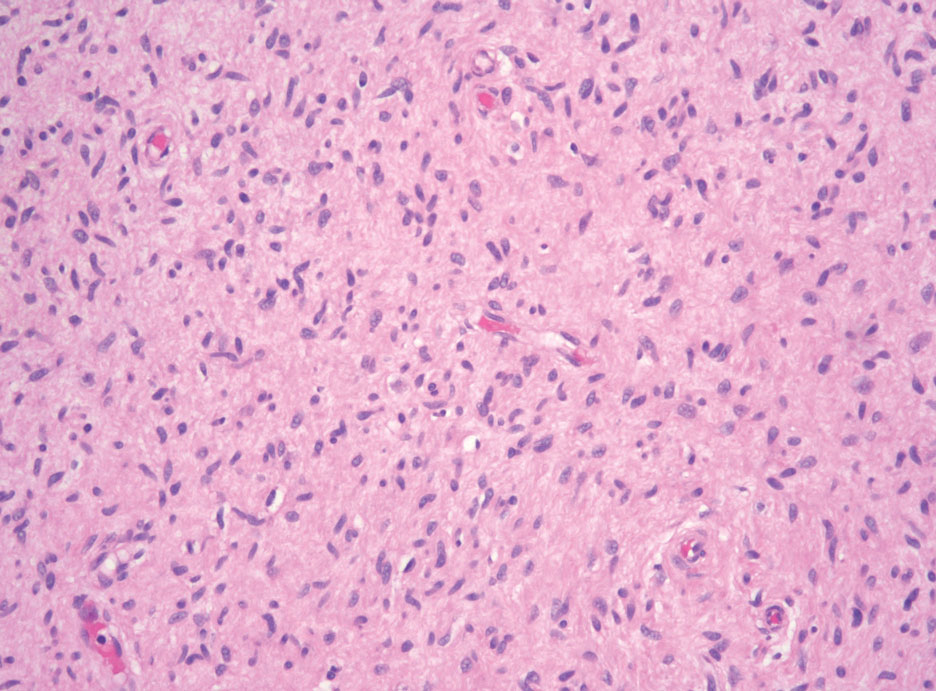

Hybrid nerve sheath tumors are rare entities that display features of more than one nerve sheath tumor such as neurofibromas, schwannomas, and perineuriomas.1 These tumors often are found in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue of the extremities and abdomen2; however, cases of hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors have been reported in many anatomical locations without a gender predilection.3 The most common type of hybrid nerve sheath tumor is a schwannoma-perineurioma.3,4 Histologically, they are well-circumscribed lesions composed of both spindled Schwann cells with plump nuclei and spindled perineural cells with more elongated thin nuclei.5 Although the Schwann cell component tends to predominate, the 2 cell populations interdigitate, making it challenging to definitively distinguish them by hematoxylin and eosin staining alone.4 However, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining can be used to help distinguish the 2 separate cell populations. Staining for S-100 and SRY-box transcription factor 10 (SOX-10) will be positive in the Schwann cell component, and staining for epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, or glucose transporter-1 (Figure 1) will be positive in the perineural component. Other hybrid forms of benign nerve sheath tumors include neurofibroma-schwannoma and neurofibromaperineurioma.4 Neurofibroma-schwannomas usually have a schwannoma component containing Antoni A areas with palisading Verocay bodies. The neurofibroma cells typically have wavy elongated nuclei, fibroblasts, and mucinous myxoid material.3 Neurofibroma-perineurioma is the least common hybrid tumor. These hybrid tumors have a plexiform neurofibroma appearance with areas of perineural differentiation, which can be difficult to identify on routine histology and typically will require IHC staining to appreciate. The neurofibroma component will stain positive for S-100 and negative for markers of perineural differentiation, including epithelial membrane antigen, glucose transporter-1, and Claudin-1.3 Although schwannoma-perineuriomas are benign sporadic tumors not associated with neurofibromatosis, neurofibromaschwannomas are associated with neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2 (NF1 and NF2). Neurofibroma-perineurioma tumors usually are associated with only NF1.3,6

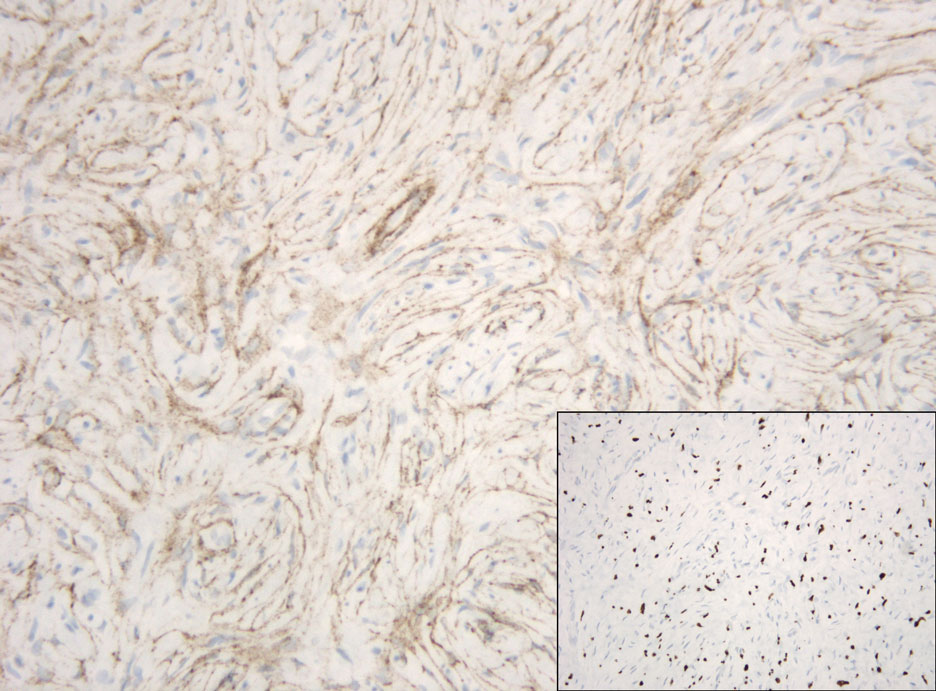

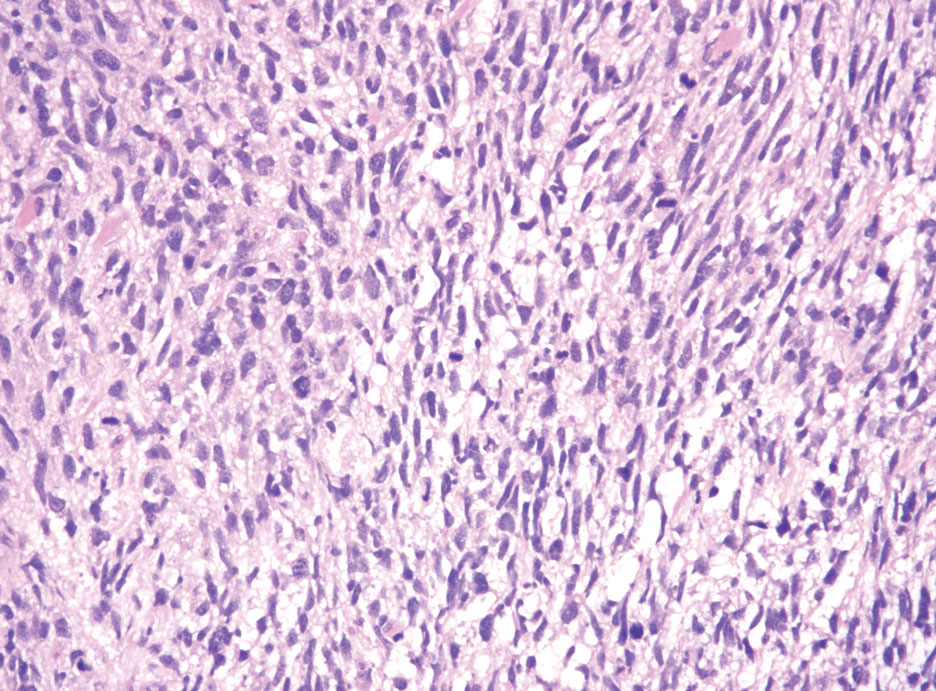

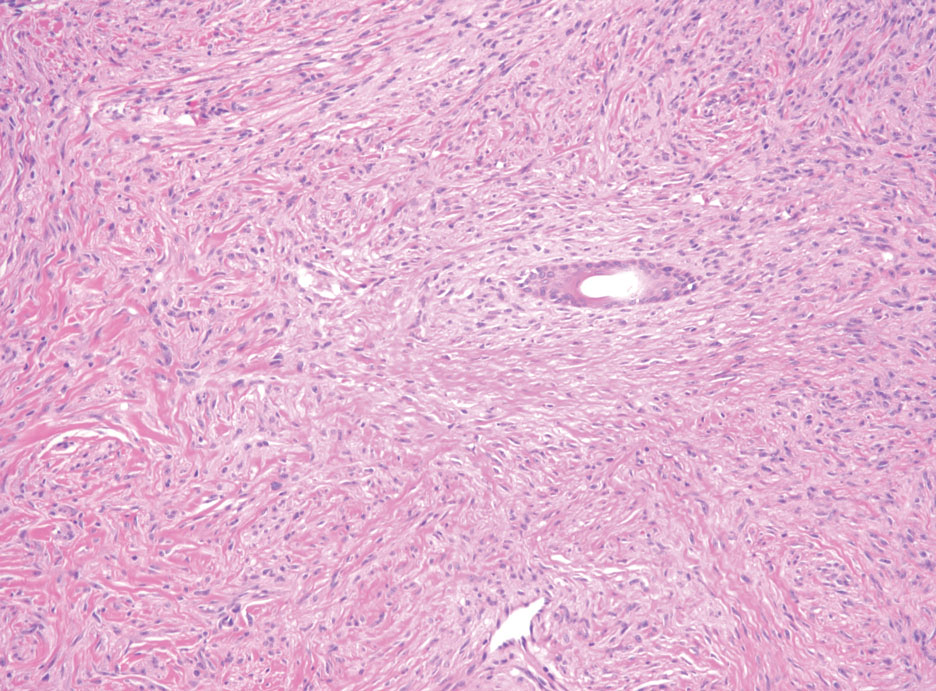

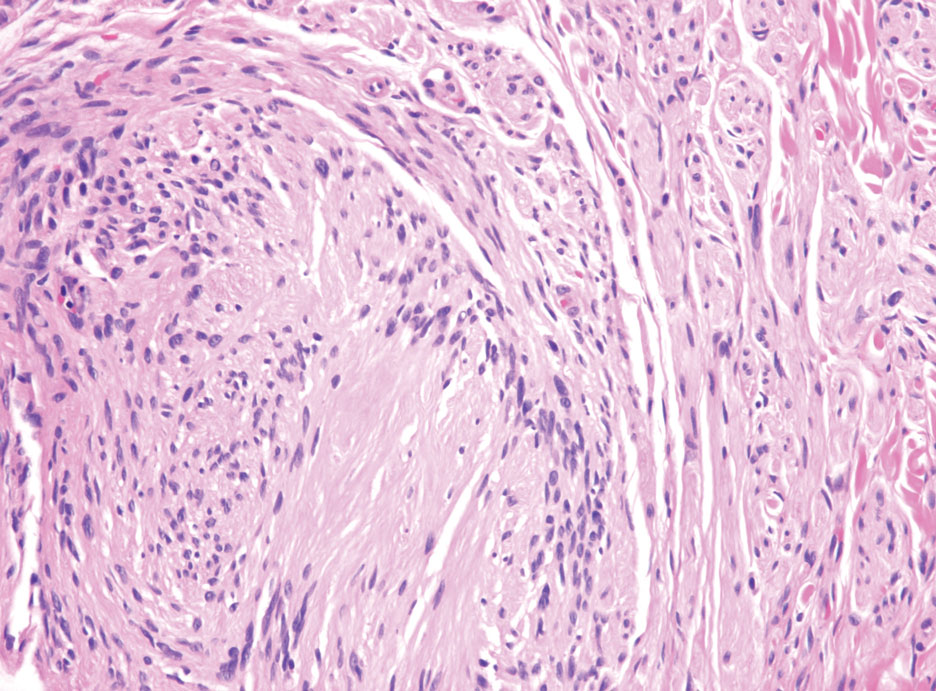

Schwannomas typically present in middle-aged patients as tumors located on flexor surfaces.7 Although perineural cells can be seen at the periphery of a schwannoma forming a capsule, they do not interdigitate between the Schwann cells. Schwannomas are composed almost entirely of well-differentiated Schwann cells.1,4,8 Schwannomas classically are well-circumscribed, encapsulated, biphasic lesions with alternating compact areas (Antoni A) and loosely arranged areas (Antoni B). The spindled cells occasionally may display nuclear palisading within the Antoni A areas, known as Verocay bodies (Figure 2). Antoni B areas are more disorganized and hypocellular with variable macrophage infiltrate.1,4,8 The Schwann cells predominantly will have bland cytologic features, but scattered areas of degenerative nuclear atypia (also known as ancient change) may be present.4 Multiple schwannomas are associated with NF2 gene mutations and loss of merlin protein.8 There are different subtypes of schwannomas, including cellular and plexiform schwannomas.4 Because schwannomas are benign nerve sheath lesions, treatment typically consists of excision with careful dissection around the involved nerve.9

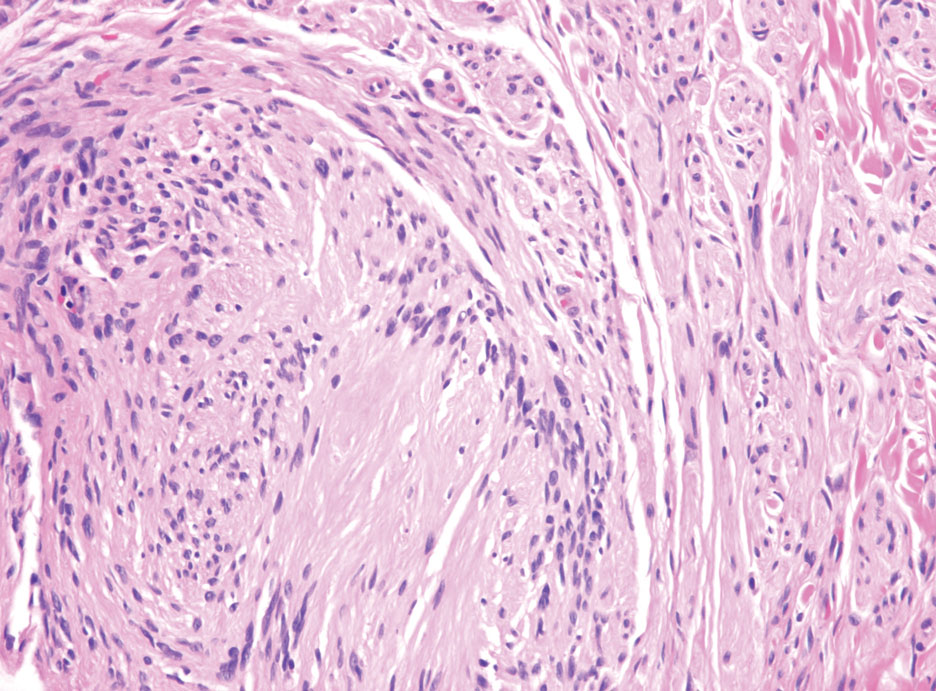

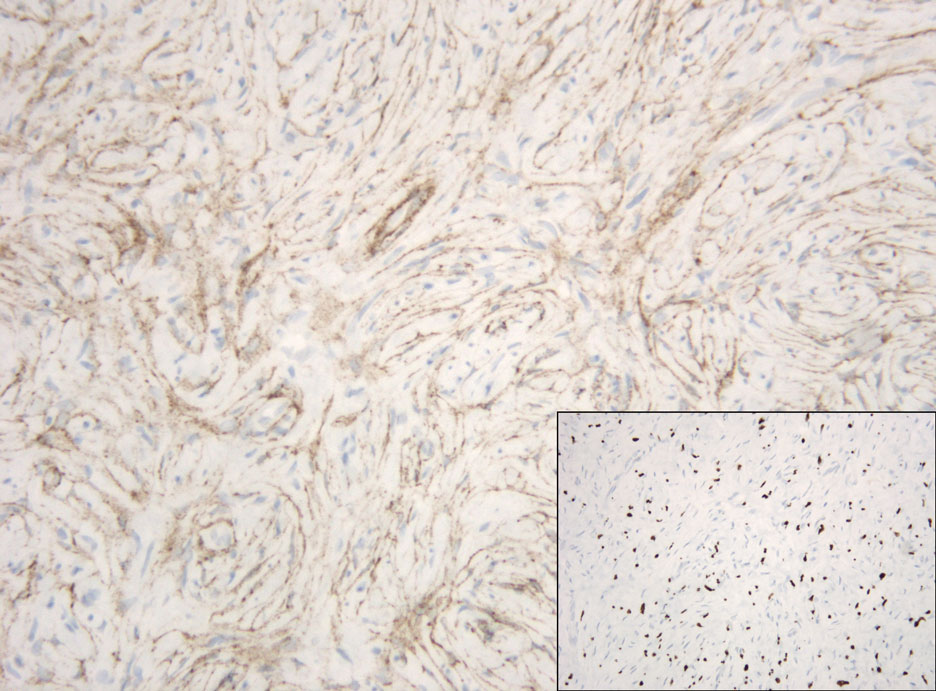

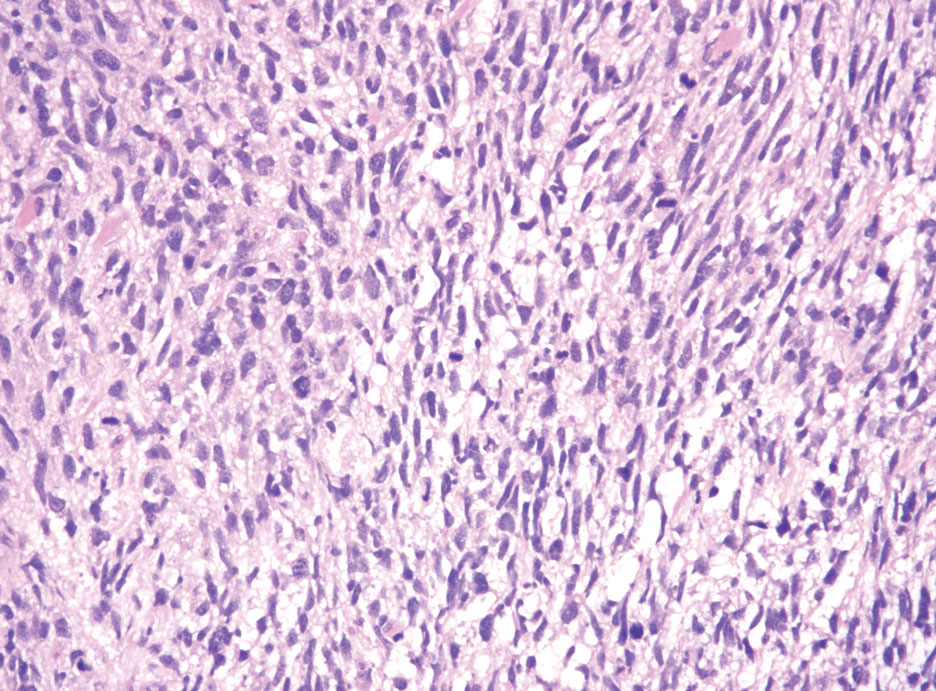

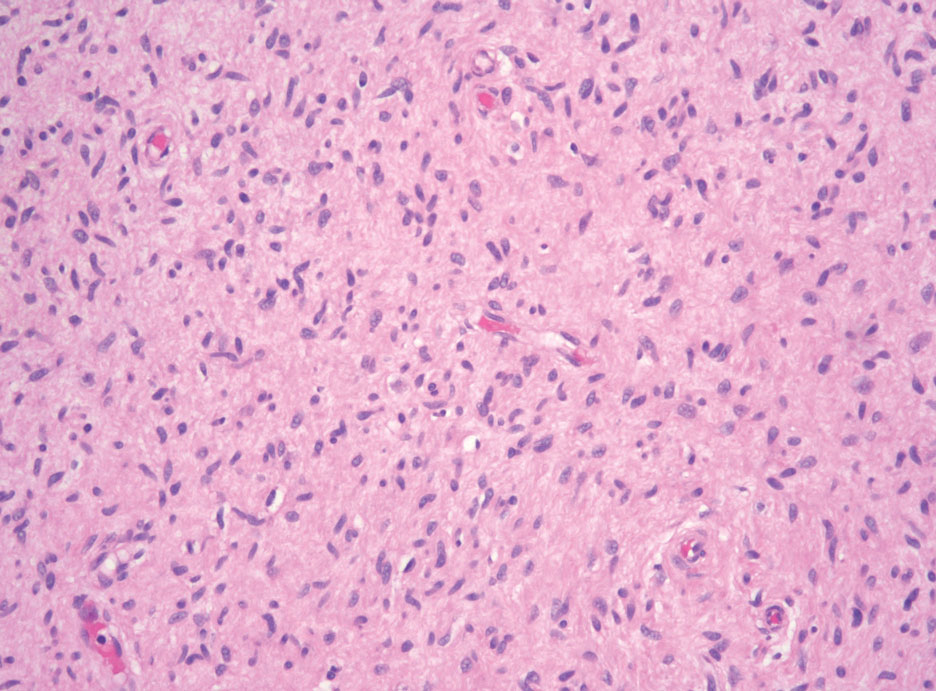

Neurofibromas are the most common peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the skin with no notable anatomic prediction, though one study found them to be more prevalent in the upper extremities.10 They typically present as sporadic solitary lesions, but multiple lesions may appear as superficial pedunculated growths that present in those aged 20 to 30 years.11 Microscopically, neurofibromas typically are not well circumscribed and have an infiltrative growth pattern. Neurofibromas are composed of cytologically bland spindled Schwann cells with thin wavy nuclei in a variable myxoid stroma (Figure 3). In addition to Schwann cells, neurofibromas contain other cell components, including fibroblasts, mast cells, perineurial-like cells, and residual axons.4 Neurofibromas typically are located in the dermis but may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Clinically, the overlying skin may show hyperpigmentation.8 Neurofibromas can be localized, diffuse, or plexiform, with the majority being localized. Diffuse neurofibromas clinically have a raised plaque appearance. Treatment is unnecessary because these lesions are benign.7

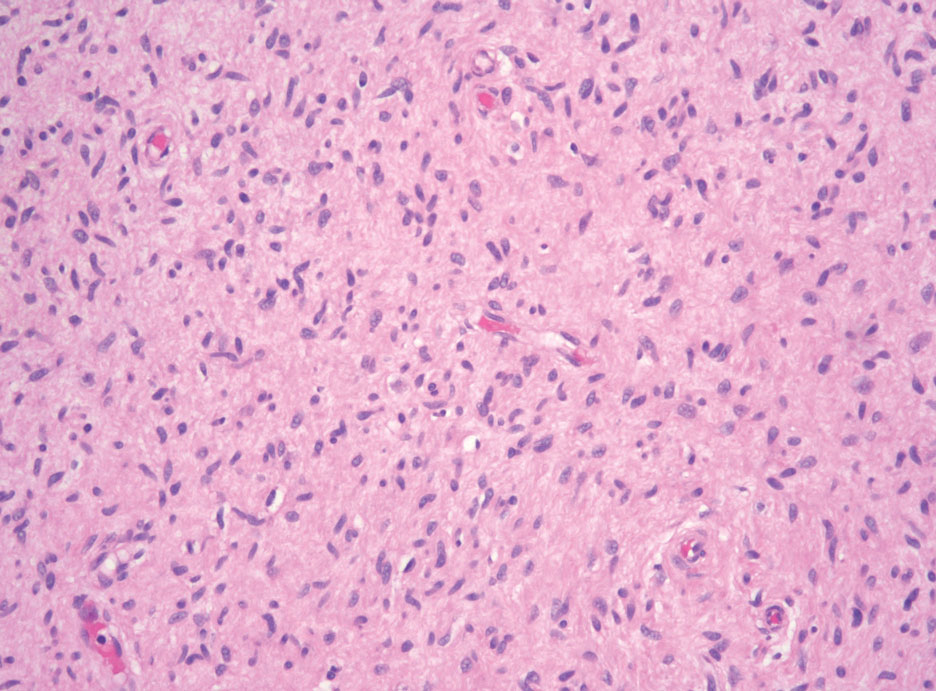

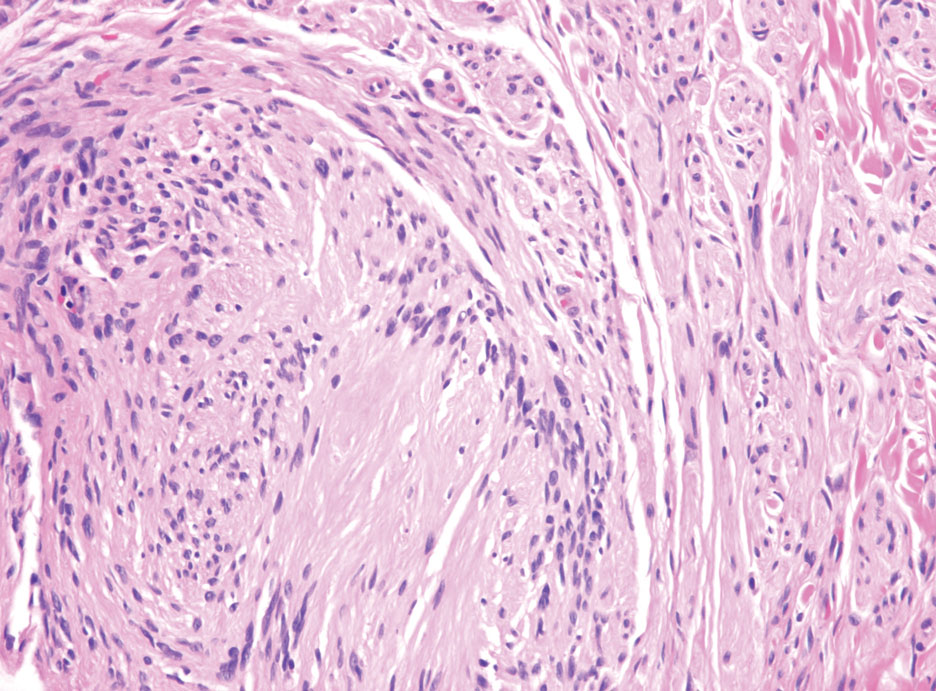

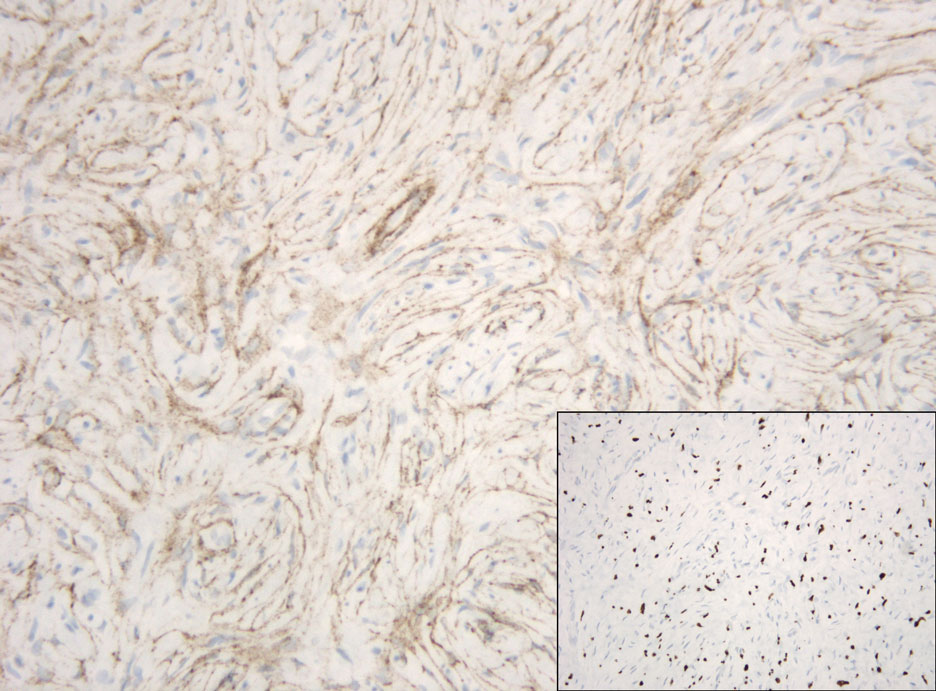

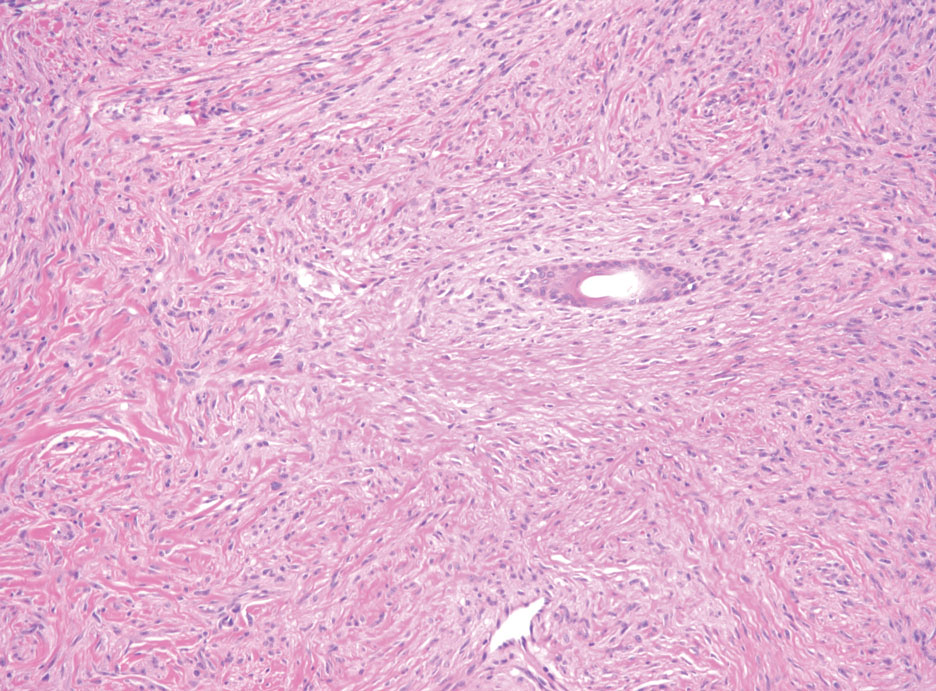

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is another diagnosis in the differential for this case. Patients with DM are older compared to non-DM melanoma patients, with a male predilection.12 Desmoplastic melanomas are more likely to be located on the head and neck. In approximately one-third of cases, no in situ component will be identified, leading to confusion of the dermal lesion as a neural lesion or an area of scar formation. Microscopically, DM presents as a variable cellular infiltrative tumor composed of spindle cells with varying degrees of nuclear atypia. The spindled melanocytes are within a collagenous (desmoplastic) stroma (Figure 4).13 Desmoplastic melanoma has been described with a low mitotic index, leading to misdiagnosis with benign spindle cell neoplasms.14 The spindle cells should be positive for S-100 and SOX-10 with IHC staining. Unlike other melanomas, human melanoma black 45 and Melan-A often are negative or only focally positive. Treatment of DM is similar to non-DM in that wide local excision usually is employed. A systematic review evaluating sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) recommended consideration of SLNB in mixed DM but not for pure DM, as rates of positive SLNB were much lower in the latter.15

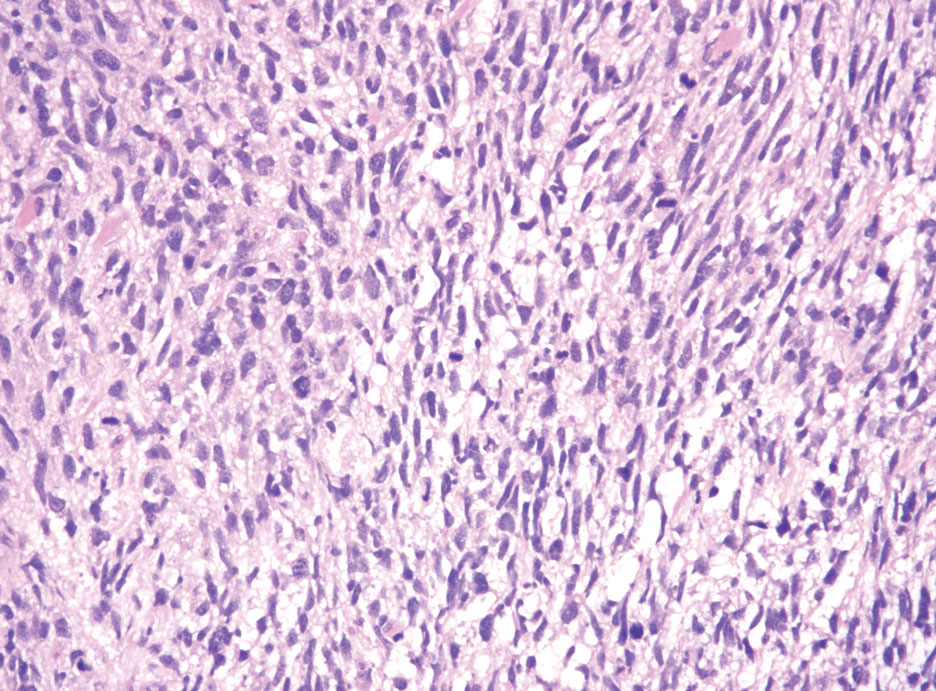

Patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) usually present with an enlarging mass, pain, or neurologic symptoms. Most cases of MPNST are located on the trunk or extremities.16 Plexiform neurofibromas, especially in adults with NF1, have the potential to transform into an MPNST.4 In fact, MPNST is the most common malignancy in patients with NF1.17 Pediatric cancer survivors also are predisposed to MPNST, with a 40-fold increase in incidence compared to the general population.18 Transformation from schwannoma to MPNST is rare but has been reported.8 Histologically, spindle cells easily can be appreciated with a fasciculated growth pattern (Figure 5). Mitotic activity and tumor necrosis may be present. Diagnosis of these tumors historically has been challenging, though recent research has identified inactivation of polycomb repressive complex 2 in 70% to 90% of MPNSTs. Because of polycomb repressive complex 2 inactivation, there is loss of stone H3K27 trimethylation that can be capitalized on for MPNST diagnosis.19 Negative IHC staining for H3K27 trimethylation has been found to be highly specific for MPNST. Negative staining for different cytokeratin and melanoma markers can be helpful in differentiating it from carcinomas and melanoma. The only curative treatment for MPNST is complete excision, leaving patients with recurrent, refractory, and metastatic cases to be encouraged for enrollment in clinical trials. The 5-year survival rates for patients with MPNST reported in the literature range from 20% to 50%.20

- Hornick JL, Bundock EA, Fletcher CD. Hybrid schwannoma /perineurioma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 distinctive benign nerve sheath tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1554-1561.

- Leung KCP, Chan E, Ng HYJ, et al. Novel case of hybrid perineuriomaneurofibroma of the orbit. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54:E283-E285.

- Ud Din N, Ahmad Z, Abdul-Ghafar J, et al. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: report of five cases and detailed review of literature. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:349. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3350-1

- Belakhoua SM, Rodriguez FJ. Diagnostic pathology of tumors of peripheral nerve. Neurosurgery. 2021;88:443-456.

- Michal M, Kazakov DV, Michal M. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a review. Cesk Patol. 2017;53:81-88.

- Harder A, Wesemann M, Hagel C, et al. Hybrid neurofibroma /schwannoma is overrepresented among schwannomatosis and neurofibromatosis patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:702-709.

- Bhattacharyya AK, Perrin R, Guha A. Peripheral nerve tumors: management strategies and molecular insights. J Neurooncol. 2004;69:335-349.

- Pytel P, Anthony DC. Peripheral nerves and skeletal muscle. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2015:1218-1239.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:246-255.

- Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, et al. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52:229-239.

- Murali R, Shaw HM, Lai K, et al. Prognostic factors in cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma: a study of 252 patients. Cancer. 2010; 116:4130-4138.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- de Almeida LS, Requena L, Rutten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215.

- Dunne JA, Wormald JC, Steele J, et al. Is sentinel lymph node biopsy warranted for desmoplastic melanoma? a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:274-280.

- Patel TD, Shaigany K, Fang CH, et al. Comparative analysis of head and neck and non-head and neck malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:113-120.

- Prudner BC, Ball T, Rathore R, et al. Diagnosis and management of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: current practice and future perspectives. Neurooncol Adv. 2020;2(suppl 1):I40-I9.

- Bright CJ, Hawkins MM, Winter DL, et al. Risk of soft-tissue sarcoma among 69,460 five-year survivors of childhood cancer in Europe. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:649-660.

- Schaefer I-M, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. Loss of H3K27 trimethylation distinguishes malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:4-13.

- Kolberg M, Holand M, Agesen TH, et al. Survival meta-analyses for >1800 malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor patients with and without neurofibromatosis type 1. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15:135-147.

The Diagnosis: Hybrid Schwannoma-Perineurioma

Hybrid nerve sheath tumors are rare entities that display features of more than one nerve sheath tumor such as neurofibromas, schwannomas, and perineuriomas.1 These tumors often are found in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue of the extremities and abdomen2; however, cases of hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors have been reported in many anatomical locations without a gender predilection.3 The most common type of hybrid nerve sheath tumor is a schwannoma-perineurioma.3,4 Histologically, they are well-circumscribed lesions composed of both spindled Schwann cells with plump nuclei and spindled perineural cells with more elongated thin nuclei.5 Although the Schwann cell component tends to predominate, the 2 cell populations interdigitate, making it challenging to definitively distinguish them by hematoxylin and eosin staining alone.4 However, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining can be used to help distinguish the 2 separate cell populations. Staining for S-100 and SRY-box transcription factor 10 (SOX-10) will be positive in the Schwann cell component, and staining for epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, or glucose transporter-1 (Figure 1) will be positive in the perineural component. Other hybrid forms of benign nerve sheath tumors include neurofibroma-schwannoma and neurofibromaperineurioma.4 Neurofibroma-schwannomas usually have a schwannoma component containing Antoni A areas with palisading Verocay bodies. The neurofibroma cells typically have wavy elongated nuclei, fibroblasts, and mucinous myxoid material.3 Neurofibroma-perineurioma is the least common hybrid tumor. These hybrid tumors have a plexiform neurofibroma appearance with areas of perineural differentiation, which can be difficult to identify on routine histology and typically will require IHC staining to appreciate. The neurofibroma component will stain positive for S-100 and negative for markers of perineural differentiation, including epithelial membrane antigen, glucose transporter-1, and Claudin-1.3 Although schwannoma-perineuriomas are benign sporadic tumors not associated with neurofibromatosis, neurofibromaschwannomas are associated with neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2 (NF1 and NF2). Neurofibroma-perineurioma tumors usually are associated with only NF1.3,6

Schwannomas typically present in middle-aged patients as tumors located on flexor surfaces.7 Although perineural cells can be seen at the periphery of a schwannoma forming a capsule, they do not interdigitate between the Schwann cells. Schwannomas are composed almost entirely of well-differentiated Schwann cells.1,4,8 Schwannomas classically are well-circumscribed, encapsulated, biphasic lesions with alternating compact areas (Antoni A) and loosely arranged areas (Antoni B). The spindled cells occasionally may display nuclear palisading within the Antoni A areas, known as Verocay bodies (Figure 2). Antoni B areas are more disorganized and hypocellular with variable macrophage infiltrate.1,4,8 The Schwann cells predominantly will have bland cytologic features, but scattered areas of degenerative nuclear atypia (also known as ancient change) may be present.4 Multiple schwannomas are associated with NF2 gene mutations and loss of merlin protein.8 There are different subtypes of schwannomas, including cellular and plexiform schwannomas.4 Because schwannomas are benign nerve sheath lesions, treatment typically consists of excision with careful dissection around the involved nerve.9

Neurofibromas are the most common peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the skin with no notable anatomic prediction, though one study found them to be more prevalent in the upper extremities.10 They typically present as sporadic solitary lesions, but multiple lesions may appear as superficial pedunculated growths that present in those aged 20 to 30 years.11 Microscopically, neurofibromas typically are not well circumscribed and have an infiltrative growth pattern. Neurofibromas are composed of cytologically bland spindled Schwann cells with thin wavy nuclei in a variable myxoid stroma (Figure 3). In addition to Schwann cells, neurofibromas contain other cell components, including fibroblasts, mast cells, perineurial-like cells, and residual axons.4 Neurofibromas typically are located in the dermis but may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Clinically, the overlying skin may show hyperpigmentation.8 Neurofibromas can be localized, diffuse, or plexiform, with the majority being localized. Diffuse neurofibromas clinically have a raised plaque appearance. Treatment is unnecessary because these lesions are benign.7

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is another diagnosis in the differential for this case. Patients with DM are older compared to non-DM melanoma patients, with a male predilection.12 Desmoplastic melanomas are more likely to be located on the head and neck. In approximately one-third of cases, no in situ component will be identified, leading to confusion of the dermal lesion as a neural lesion or an area of scar formation. Microscopically, DM presents as a variable cellular infiltrative tumor composed of spindle cells with varying degrees of nuclear atypia. The spindled melanocytes are within a collagenous (desmoplastic) stroma (Figure 4).13 Desmoplastic melanoma has been described with a low mitotic index, leading to misdiagnosis with benign spindle cell neoplasms.14 The spindle cells should be positive for S-100 and SOX-10 with IHC staining. Unlike other melanomas, human melanoma black 45 and Melan-A often are negative or only focally positive. Treatment of DM is similar to non-DM in that wide local excision usually is employed. A systematic review evaluating sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) recommended consideration of SLNB in mixed DM but not for pure DM, as rates of positive SLNB were much lower in the latter.15

Patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) usually present with an enlarging mass, pain, or neurologic symptoms. Most cases of MPNST are located on the trunk or extremities.16 Plexiform neurofibromas, especially in adults with NF1, have the potential to transform into an MPNST.4 In fact, MPNST is the most common malignancy in patients with NF1.17 Pediatric cancer survivors also are predisposed to MPNST, with a 40-fold increase in incidence compared to the general population.18 Transformation from schwannoma to MPNST is rare but has been reported.8 Histologically, spindle cells easily can be appreciated with a fasciculated growth pattern (Figure 5). Mitotic activity and tumor necrosis may be present. Diagnosis of these tumors historically has been challenging, though recent research has identified inactivation of polycomb repressive complex 2 in 70% to 90% of MPNSTs. Because of polycomb repressive complex 2 inactivation, there is loss of stone H3K27 trimethylation that can be capitalized on for MPNST diagnosis.19 Negative IHC staining for H3K27 trimethylation has been found to be highly specific for MPNST. Negative staining for different cytokeratin and melanoma markers can be helpful in differentiating it from carcinomas and melanoma. The only curative treatment for MPNST is complete excision, leaving patients with recurrent, refractory, and metastatic cases to be encouraged for enrollment in clinical trials. The 5-year survival rates for patients with MPNST reported in the literature range from 20% to 50%.20

The Diagnosis: Hybrid Schwannoma-Perineurioma

Hybrid nerve sheath tumors are rare entities that display features of more than one nerve sheath tumor such as neurofibromas, schwannomas, and perineuriomas.1 These tumors often are found in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue of the extremities and abdomen2; however, cases of hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors have been reported in many anatomical locations without a gender predilection.3 The most common type of hybrid nerve sheath tumor is a schwannoma-perineurioma.3,4 Histologically, they are well-circumscribed lesions composed of both spindled Schwann cells with plump nuclei and spindled perineural cells with more elongated thin nuclei.5 Although the Schwann cell component tends to predominate, the 2 cell populations interdigitate, making it challenging to definitively distinguish them by hematoxylin and eosin staining alone.4 However, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining can be used to help distinguish the 2 separate cell populations. Staining for S-100 and SRY-box transcription factor 10 (SOX-10) will be positive in the Schwann cell component, and staining for epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, or glucose transporter-1 (Figure 1) will be positive in the perineural component. Other hybrid forms of benign nerve sheath tumors include neurofibroma-schwannoma and neurofibromaperineurioma.4 Neurofibroma-schwannomas usually have a schwannoma component containing Antoni A areas with palisading Verocay bodies. The neurofibroma cells typically have wavy elongated nuclei, fibroblasts, and mucinous myxoid material.3 Neurofibroma-perineurioma is the least common hybrid tumor. These hybrid tumors have a plexiform neurofibroma appearance with areas of perineural differentiation, which can be difficult to identify on routine histology and typically will require IHC staining to appreciate. The neurofibroma component will stain positive for S-100 and negative for markers of perineural differentiation, including epithelial membrane antigen, glucose transporter-1, and Claudin-1.3 Although schwannoma-perineuriomas are benign sporadic tumors not associated with neurofibromatosis, neurofibromaschwannomas are associated with neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2 (NF1 and NF2). Neurofibroma-perineurioma tumors usually are associated with only NF1.3,6

Schwannomas typically present in middle-aged patients as tumors located on flexor surfaces.7 Although perineural cells can be seen at the periphery of a schwannoma forming a capsule, they do not interdigitate between the Schwann cells. Schwannomas are composed almost entirely of well-differentiated Schwann cells.1,4,8 Schwannomas classically are well-circumscribed, encapsulated, biphasic lesions with alternating compact areas (Antoni A) and loosely arranged areas (Antoni B). The spindled cells occasionally may display nuclear palisading within the Antoni A areas, known as Verocay bodies (Figure 2). Antoni B areas are more disorganized and hypocellular with variable macrophage infiltrate.1,4,8 The Schwann cells predominantly will have bland cytologic features, but scattered areas of degenerative nuclear atypia (also known as ancient change) may be present.4 Multiple schwannomas are associated with NF2 gene mutations and loss of merlin protein.8 There are different subtypes of schwannomas, including cellular and plexiform schwannomas.4 Because schwannomas are benign nerve sheath lesions, treatment typically consists of excision with careful dissection around the involved nerve.9

Neurofibromas are the most common peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the skin with no notable anatomic prediction, though one study found them to be more prevalent in the upper extremities.10 They typically present as sporadic solitary lesions, but multiple lesions may appear as superficial pedunculated growths that present in those aged 20 to 30 years.11 Microscopically, neurofibromas typically are not well circumscribed and have an infiltrative growth pattern. Neurofibromas are composed of cytologically bland spindled Schwann cells with thin wavy nuclei in a variable myxoid stroma (Figure 3). In addition to Schwann cells, neurofibromas contain other cell components, including fibroblasts, mast cells, perineurial-like cells, and residual axons.4 Neurofibromas typically are located in the dermis but may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Clinically, the overlying skin may show hyperpigmentation.8 Neurofibromas can be localized, diffuse, or plexiform, with the majority being localized. Diffuse neurofibromas clinically have a raised plaque appearance. Treatment is unnecessary because these lesions are benign.7

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is another diagnosis in the differential for this case. Patients with DM are older compared to non-DM melanoma patients, with a male predilection.12 Desmoplastic melanomas are more likely to be located on the head and neck. In approximately one-third of cases, no in situ component will be identified, leading to confusion of the dermal lesion as a neural lesion or an area of scar formation. Microscopically, DM presents as a variable cellular infiltrative tumor composed of spindle cells with varying degrees of nuclear atypia. The spindled melanocytes are within a collagenous (desmoplastic) stroma (Figure 4).13 Desmoplastic melanoma has been described with a low mitotic index, leading to misdiagnosis with benign spindle cell neoplasms.14 The spindle cells should be positive for S-100 and SOX-10 with IHC staining. Unlike other melanomas, human melanoma black 45 and Melan-A often are negative or only focally positive. Treatment of DM is similar to non-DM in that wide local excision usually is employed. A systematic review evaluating sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) recommended consideration of SLNB in mixed DM but not for pure DM, as rates of positive SLNB were much lower in the latter.15

Patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) usually present with an enlarging mass, pain, or neurologic symptoms. Most cases of MPNST are located on the trunk or extremities.16 Plexiform neurofibromas, especially in adults with NF1, have the potential to transform into an MPNST.4 In fact, MPNST is the most common malignancy in patients with NF1.17 Pediatric cancer survivors also are predisposed to MPNST, with a 40-fold increase in incidence compared to the general population.18 Transformation from schwannoma to MPNST is rare but has been reported.8 Histologically, spindle cells easily can be appreciated with a fasciculated growth pattern (Figure 5). Mitotic activity and tumor necrosis may be present. Diagnosis of these tumors historically has been challenging, though recent research has identified inactivation of polycomb repressive complex 2 in 70% to 90% of MPNSTs. Because of polycomb repressive complex 2 inactivation, there is loss of stone H3K27 trimethylation that can be capitalized on for MPNST diagnosis.19 Negative IHC staining for H3K27 trimethylation has been found to be highly specific for MPNST. Negative staining for different cytokeratin and melanoma markers can be helpful in differentiating it from carcinomas and melanoma. The only curative treatment for MPNST is complete excision, leaving patients with recurrent, refractory, and metastatic cases to be encouraged for enrollment in clinical trials. The 5-year survival rates for patients with MPNST reported in the literature range from 20% to 50%.20

- Hornick JL, Bundock EA, Fletcher CD. Hybrid schwannoma /perineurioma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 distinctive benign nerve sheath tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1554-1561.

- Leung KCP, Chan E, Ng HYJ, et al. Novel case of hybrid perineuriomaneurofibroma of the orbit. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54:E283-E285.

- Ud Din N, Ahmad Z, Abdul-Ghafar J, et al. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: report of five cases and detailed review of literature. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:349. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3350-1

- Belakhoua SM, Rodriguez FJ. Diagnostic pathology of tumors of peripheral nerve. Neurosurgery. 2021;88:443-456.

- Michal M, Kazakov DV, Michal M. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a review. Cesk Patol. 2017;53:81-88.

- Harder A, Wesemann M, Hagel C, et al. Hybrid neurofibroma /schwannoma is overrepresented among schwannomatosis and neurofibromatosis patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:702-709.

- Bhattacharyya AK, Perrin R, Guha A. Peripheral nerve tumors: management strategies and molecular insights. J Neurooncol. 2004;69:335-349.

- Pytel P, Anthony DC. Peripheral nerves and skeletal muscle. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2015:1218-1239.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:246-255.

- Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, et al. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52:229-239.

- Murali R, Shaw HM, Lai K, et al. Prognostic factors in cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma: a study of 252 patients. Cancer. 2010; 116:4130-4138.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- de Almeida LS, Requena L, Rutten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215.

- Dunne JA, Wormald JC, Steele J, et al. Is sentinel lymph node biopsy warranted for desmoplastic melanoma? a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:274-280.

- Patel TD, Shaigany K, Fang CH, et al. Comparative analysis of head and neck and non-head and neck malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:113-120.

- Prudner BC, Ball T, Rathore R, et al. Diagnosis and management of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: current practice and future perspectives. Neurooncol Adv. 2020;2(suppl 1):I40-I9.

- Bright CJ, Hawkins MM, Winter DL, et al. Risk of soft-tissue sarcoma among 69,460 five-year survivors of childhood cancer in Europe. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:649-660.

- Schaefer I-M, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. Loss of H3K27 trimethylation distinguishes malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:4-13.

- Kolberg M, Holand M, Agesen TH, et al. Survival meta-analyses for >1800 malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor patients with and without neurofibromatosis type 1. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15:135-147.

- Hornick JL, Bundock EA, Fletcher CD. Hybrid schwannoma /perineurioma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 distinctive benign nerve sheath tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1554-1561.

- Leung KCP, Chan E, Ng HYJ, et al. Novel case of hybrid perineuriomaneurofibroma of the orbit. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54:E283-E285.

- Ud Din N, Ahmad Z, Abdul-Ghafar J, et al. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: report of five cases and detailed review of literature. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:349. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3350-1

- Belakhoua SM, Rodriguez FJ. Diagnostic pathology of tumors of peripheral nerve. Neurosurgery. 2021;88:443-456.

- Michal M, Kazakov DV, Michal M. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a review. Cesk Patol. 2017;53:81-88.

- Harder A, Wesemann M, Hagel C, et al. Hybrid neurofibroma /schwannoma is overrepresented among schwannomatosis and neurofibromatosis patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:702-709.

- Bhattacharyya AK, Perrin R, Guha A. Peripheral nerve tumors: management strategies and molecular insights. J Neurooncol. 2004;69:335-349.

- Pytel P, Anthony DC. Peripheral nerves and skeletal muscle. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2015:1218-1239.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:246-255.

- Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, et al. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52:229-239.

- Murali R, Shaw HM, Lai K, et al. Prognostic factors in cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma: a study of 252 patients. Cancer. 2010; 116:4130-4138.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- de Almeida LS, Requena L, Rutten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215.

- Dunne JA, Wormald JC, Steele J, et al. Is sentinel lymph node biopsy warranted for desmoplastic melanoma? a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:274-280.

- Patel TD, Shaigany K, Fang CH, et al. Comparative analysis of head and neck and non-head and neck malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:113-120.

- Prudner BC, Ball T, Rathore R, et al. Diagnosis and management of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: current practice and future perspectives. Neurooncol Adv. 2020;2(suppl 1):I40-I9.

- Bright CJ, Hawkins MM, Winter DL, et al. Risk of soft-tissue sarcoma among 69,460 five-year survivors of childhood cancer in Europe. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:649-660.

- Schaefer I-M, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. Loss of H3K27 trimethylation distinguishes malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:4-13.

- Kolberg M, Holand M, Agesen TH, et al. Survival meta-analyses for >1800 malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor patients with and without neurofibromatosis type 1. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15:135-147.

A 50-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, subcutaneous, freely mobile nodule on the occipital scalp that first appeared 35 years prior but recently had started enlarging. Histologically the lesion was well circumscribed. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for SRY-box transcription factor 10 in some of the spindle cells, and staining for epithelial membrane antigen was positive in a separate population of intermixed spindle cells.

Levamisole-Induced Vasculopathy With Gastric Involvement in a Cocaine User

In 2010, two separate reports of cutaneous vasculitic/vasculopathic eruptions in patients with recent exposure to levamisole-contaminated cocaine (LCC) were published in the literature.1,2 Since then, additional reports have been published.3-6 Retiform purpura associated with cocaine use appears to be a similar condition, perhaps lying at one end of the spectrum of LCC-induced cutaneous vascular disease.7,8 Although some patients have been described as having nausea and vomiting,8,9 including one with a sudden drop in hemoglobin to 5.8 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL),10 there are no known reported cases of LCC and levamisole-induced vasculopathy in organ systems other than the skin. Herein, we report the case of a patient with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV) demonstrating endoscopic evidence of gastric hemorrhage with features similar to those involving the skin.

Case Report

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C, intravenous drug abuse, and bipolar disorder presented to the emergency department with painful necrotic lesions on the head, neck, arms, and legs of several days’ duration. Approximately 1 year prior she had been admitted to the hospital with similar lesions, with eventual partial necrosis of the left earlobe. The patient reported she had last used crack cocaine 3 days prior to the development of the lesions. A urine drug screen was positive for lorazepam, alprazolam, buprenorphine, methadone, tetrahydrocannabinol, and cocaine. She also reported abdominal pain and gastric reflux of recent onset but denied any history of gastrointestinal tract disease. During the previous admission, the patient demonstrated antinuclear antibodies at a titer of greater than 1:160 (normal, <1:40) in a smooth pattern as well as positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) and cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA) and positive cryoglobulins. Physical examination yielded purpuric and hemorrhagic patches and plaques on the nose, bilateral ears (Figure 1A), face (Figure 1B), arms, and legs. Older lesions exhibited evidence of evolving erosion and ulceration. A biopsy of a lesion on the right arm was obtained, demonstrating extensive epidermal necrosis, hemorrhage, fibrin thrombi within dermal blood vessels, fibrinoid mural necrosis, perivascular neutrophils, and leukocytoclasis (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with LIV caused by exposure to LCC. A complete blood cell count was unremarkable. She was started on pain management and was given prednisone to treat the cutaneous eruption. Because of continued reports of epigastric pain and discomfort on swallowing, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed. Numerous esophageal erosions and gastric submucosal hemorrhages similar to those on the skin were noted (Figure 3). Pathology taken at the time of the endoscopy demonstrated mucosal erosions, but an evaluation for vascular insult was not possible, as submucosal tissue was not obtained. As the skin lesions began to heal, the gastric symptoms gradually subsided, and the patient was released from the hospital after 7 days.

Comment

Levamisole-Contaminated Cocaine

Cocaine is a crystalline alkaloid obtained from the leaves of the coca plant.7 Fifty percent of globally produced cocaine is consumed in the United States.10 There are 2 to 5 million cocaine users in the United States; in 2009, a reported 1.6 million US adults admitted to having used cocaine in the previous month.4,11,12 Cocaine has been known to be cut with similar-appearing substances including lactose and mannitol, though caffeine, acetaminophen, methylphenidate, and other ingredients have been utilized.7

Levamisole is a synthetic imidazothiazole derivative initially developed for use as an immunomodulatory agent in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.4 It was later paired with 5-fluorouracil for administration in patients with carcinomas of the colon and breasts.4,13 In 2000, the drug was withdrawn from the US market for use in humans after an association between levamisole and agranulocytosis was noted in 2.5% to 13% of patients taking the drug for rheumatoid arthritis or as an adjuvant therapy for breast carcinoma.9,12 It still is available for veterinary use as an anthelmintic and is administered to humans in other countries. Levamisole acts as an immunomodulator by enhancing macrophage chemotaxis and upregulating T-cell functions as well as stimulating neutrophil chemotaxis and dendritic cell maturation.4 It also is known to generate autoantibodies including lupus anticoagulant, p-ANCA, c-ANCA, and antinuclear antibodies.7,14 Levamisole is known to exhibit cutaneous reactions. In 1999, Rongioletti et al14 reported 5 children with purpura of the ears who had been given levamisole for pediatric nephrotic syndrome. Involvement of other body areas was noted. Three patients developed lupus anticoagulant antibodies, 3 exhibited p-ANCA antibodies, and 1 was positive for c-ANCA antibodies. The investigators noted an exceptionally long latency period of 12 to 44 months after starting the drug. Histologically a vasculopathic/vasculitic process was noted.14 Direct immunofluorescence studies of affected skin in LIV have demonstrated IgM, IgA, IgG, C3, and fibrin staining of blood vessels.4,15 Anti–human elastase antibodies are considered both sensitive and specific for LIV and serve to differentiate it from cocaine-induced pseudovasculitis.4,7

In April 2008, the New Mexico Department of Health began evaluating several unexplained cases of agranulocytosis and noted that 11 of 21 cases were associated with cocaine use.9 Later that year, public health workers in Alberta and British Columbia, Canada, reported finding traces of levamisole in clinical specimens and drug paraphernalia of cocaine users with agranulocytosis. Officials from the New Mexico Department of Health learned of these findings and investigated the cases, finding 7 of 9 patients with idiopathic agranulocytosis had recent exposure to cocaine. None of the 21 total patients experienced any skin findings. Nausea and vomiting were common symptoms, but abdominal pain was described in only 2 patients from an additional investigation in Washington. Both of these patients used crack cocaine, and one had a positive urine test for levamisole.9

The presence of levamisole initially was detected by the US Drug Enforcement Administration in 2003. By July 2009, 69% of cocaine and 3% of heroin seized by this agency was noted to contain levamisole.16 From 2003 to 2009, the concentration of levamisole contamination rose to 10%.4 A 2011 study found levamisole in 194 of 249 cocaine-positive urine samples.16

It is unclear why cocaine producers add levamisoleto their product. Possibilities include increasing the drug’s bulk or enhancing its stimulatory effects.12 Chang et al17 posited that levamisole increases the stimulatory and euphoric effects of cocaine by increasing dopamine levels in the brain. Additionally, levamisole is metabolized to aminorex, an amphetaminelike hallucinogen that suppresses appetite, in patients with LCC.13 Vagi et al12 interviewed 10 patients who had been hospitalized for agranulocytosis secondary to use of LCC. None were aware of the presence of this additive, suggesting it was not used as a marketing tool.

Cutaneous Vasculopathy

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy (also called levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy11) initially was reported by 2 separate groups in 2010.1,2 Patients typically present with tender purpuric to hemorrhagic papules, plaques, and bullae with an affinity to affect the ears, nose, and face, though other areas of the body can be affected. A pattern of retiform purpura may precede these findings in some patients. Women are disproportionately affected.11 Crack cocaine use is overrepresented in LIV compared to insufflation or snorting of the drug. Affected patients may exhibit systemic symptoms including myalgia, arthralgia, and frank arthritis.10 Additionally, 15% to 80% of patients exhibit positive antinuclear antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant antibodies, p-ANCA antibodies, and c-ANCA antibodies. Magro and Wang8 hypothesized that levamisole acting in conjunction with cocaine rather than the effects of levamisole alone is responsible for some of these findings.

Histologically, the features of a vasculopathic process are noted in some patients with the presence of frank vasculitis.1 The vasculopathic component demonstrates vessel dilatation with thrombosis, eosinophilic deposits, and erythrocyte extravasation. Patients with frank vasculitis exhibit fibrinoid vessel wall necrosis and fibrin deposition, extravasated erythrocytes, endothelial cell atypia, and leukocytoclasia.3 Jacob et al3 noted interstitial and perivascular neovascularization in affected tissue, believed to represent one stage in the evolution of medium vessel vasculitis. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 has been reported in affected vessel walls with endothelial caspase 3 expression and C5b-9 deposition.8 Magro and Wang8 believe the retiform purpura seen in the early stages of some of these patients with LIV represents a thrombotic dynamic with C5b-9 deposition and enhanced apoptosis. Overt vasculitis follows later, subsequent to the effect of ANCA antibodies and upregulated intercellular adhesion molecule 1 expression on vessel walls.

The clinical course of LIV typically is 2 to 3 weeks for lesion resolution; however, normalization of serologies may require 2 to 14 months. Observation and pain control with or without administration of systemic steroids is sufficient for most patients, but skin grafting, wound debridement, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and plasmapheresis also have been employed.4,5 Morbidity may be substantive. One report noted LCC to be responsible for 3 cases of pulmonary hemorrhage and acute progression to chronic renal failure in another 2 patients.15 Ching and Smith18 described a patient with 52% total body surface area involvement who required skin grafting, nasal amputation, patellectomy, central upper lip excision, and amputation of the leg above the knee.

Gastrointestinal Presentation

Patients with LIV have been reported to exhibit abdominal pain, but our patient exhibited a rare presentation of visualized gastrointestinal purpura. Although support for a vasculitic/vasculopathic process requires a tissue diagnosis, the endoscopic appearance of gastric vasculitis is similar to that of cutaneous vasculitis.19 Clinicians caring for patients exposed to LCC should bear in mind that the vascular insults associated with LIV are not restricted solely to the skin.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Bradford M, Rosenberg B, Moreno J, et al. Bilateral necrosis of earlobes and cheeks: another complication of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. Ann Int Med. 2010;152:758-759.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Lee KC, Ladizinski B, Federman DG. Complications associated with use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine: an emerging public health challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:581-586.

- Pavenski K, Vandenberghe H, Jakubovic H, et al. Plasmapheresis and steroid treatment of levamisole-induced vasculopathy and associated skin necrosis in crack/cocaine users. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:123-126.

- Mandrell J, Kranc CL. Prednisone and vardenafil hydrochloride refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Cutis. 2016;98:E15-E19.

- Walsh NM, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole [published online August 25, 2010]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Magro CM, Wang X. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura: a C5b-9 mediated microangiopathy syndrome associated with enhanced apoptosis and high levels of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression. Am J Dermatopathol 2013;35:722-730.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Agranulocytosis associated with cocaine use—four states, March 2008-November 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1381-1385.

- Espinoza LR, Alamino RP. Cocaine-induced vasculitis: clinical and immunological spectrum. Curr Rhematol Rep. 2012;14:532-538.

- Arora NP. Cutaneous vasculopathy and neutropenia associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345:45-51.

- Vagi SJ, Sheikh S, Brackney M, et al. Passive multistate surveillance for neutropenia after of cocaine or heroin possibly contaminated with levamisole. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:468-474.

- Lee KC, Ladizinski, Nutan FN. Systemic complications of levamisole toxicity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:791-792.

- Rongioletti E, Ghio L, Ginervri E, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating longer-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- McGrath MM, Isakova T, Rennke HG, et al. Contaminated cocaine and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2799-2805.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Chang A, Osterloh J, Thomas J. Levamisole: a dangerous new cocaine adulterant. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:408-411.

- Ching JA, Smith DJ. Levamisole-induced necrosis of skin, soft-tissue and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:E1-E5.

- Naruse G, Shimata K. Cutaneous and gastrointestinal purpura. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1843.

In 2010, two separate reports of cutaneous vasculitic/vasculopathic eruptions in patients with recent exposure to levamisole-contaminated cocaine (LCC) were published in the literature.1,2 Since then, additional reports have been published.3-6 Retiform purpura associated with cocaine use appears to be a similar condition, perhaps lying at one end of the spectrum of LCC-induced cutaneous vascular disease.7,8 Although some patients have been described as having nausea and vomiting,8,9 including one with a sudden drop in hemoglobin to 5.8 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL),10 there are no known reported cases of LCC and levamisole-induced vasculopathy in organ systems other than the skin. Herein, we report the case of a patient with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV) demonstrating endoscopic evidence of gastric hemorrhage with features similar to those involving the skin.

Case Report

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C, intravenous drug abuse, and bipolar disorder presented to the emergency department with painful necrotic lesions on the head, neck, arms, and legs of several days’ duration. Approximately 1 year prior she had been admitted to the hospital with similar lesions, with eventual partial necrosis of the left earlobe. The patient reported she had last used crack cocaine 3 days prior to the development of the lesions. A urine drug screen was positive for lorazepam, alprazolam, buprenorphine, methadone, tetrahydrocannabinol, and cocaine. She also reported abdominal pain and gastric reflux of recent onset but denied any history of gastrointestinal tract disease. During the previous admission, the patient demonstrated antinuclear antibodies at a titer of greater than 1:160 (normal, <1:40) in a smooth pattern as well as positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) and cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA) and positive cryoglobulins. Physical examination yielded purpuric and hemorrhagic patches and plaques on the nose, bilateral ears (Figure 1A), face (Figure 1B), arms, and legs. Older lesions exhibited evidence of evolving erosion and ulceration. A biopsy of a lesion on the right arm was obtained, demonstrating extensive epidermal necrosis, hemorrhage, fibrin thrombi within dermal blood vessels, fibrinoid mural necrosis, perivascular neutrophils, and leukocytoclasis (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with LIV caused by exposure to LCC. A complete blood cell count was unremarkable. She was started on pain management and was given prednisone to treat the cutaneous eruption. Because of continued reports of epigastric pain and discomfort on swallowing, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed. Numerous esophageal erosions and gastric submucosal hemorrhages similar to those on the skin were noted (Figure 3). Pathology taken at the time of the endoscopy demonstrated mucosal erosions, but an evaluation for vascular insult was not possible, as submucosal tissue was not obtained. As the skin lesions began to heal, the gastric symptoms gradually subsided, and the patient was released from the hospital after 7 days.

Comment

Levamisole-Contaminated Cocaine

Cocaine is a crystalline alkaloid obtained from the leaves of the coca plant.7 Fifty percent of globally produced cocaine is consumed in the United States.10 There are 2 to 5 million cocaine users in the United States; in 2009, a reported 1.6 million US adults admitted to having used cocaine in the previous month.4,11,12 Cocaine has been known to be cut with similar-appearing substances including lactose and mannitol, though caffeine, acetaminophen, methylphenidate, and other ingredients have been utilized.7

Levamisole is a synthetic imidazothiazole derivative initially developed for use as an immunomodulatory agent in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.4 It was later paired with 5-fluorouracil for administration in patients with carcinomas of the colon and breasts.4,13 In 2000, the drug was withdrawn from the US market for use in humans after an association between levamisole and agranulocytosis was noted in 2.5% to 13% of patients taking the drug for rheumatoid arthritis or as an adjuvant therapy for breast carcinoma.9,12 It still is available for veterinary use as an anthelmintic and is administered to humans in other countries. Levamisole acts as an immunomodulator by enhancing macrophage chemotaxis and upregulating T-cell functions as well as stimulating neutrophil chemotaxis and dendritic cell maturation.4 It also is known to generate autoantibodies including lupus anticoagulant, p-ANCA, c-ANCA, and antinuclear antibodies.7,14 Levamisole is known to exhibit cutaneous reactions. In 1999, Rongioletti et al14 reported 5 children with purpura of the ears who had been given levamisole for pediatric nephrotic syndrome. Involvement of other body areas was noted. Three patients developed lupus anticoagulant antibodies, 3 exhibited p-ANCA antibodies, and 1 was positive for c-ANCA antibodies. The investigators noted an exceptionally long latency period of 12 to 44 months after starting the drug. Histologically a vasculopathic/vasculitic process was noted.14 Direct immunofluorescence studies of affected skin in LIV have demonstrated IgM, IgA, IgG, C3, and fibrin staining of blood vessels.4,15 Anti–human elastase antibodies are considered both sensitive and specific for LIV and serve to differentiate it from cocaine-induced pseudovasculitis.4,7

In April 2008, the New Mexico Department of Health began evaluating several unexplained cases of agranulocytosis and noted that 11 of 21 cases were associated with cocaine use.9 Later that year, public health workers in Alberta and British Columbia, Canada, reported finding traces of levamisole in clinical specimens and drug paraphernalia of cocaine users with agranulocytosis. Officials from the New Mexico Department of Health learned of these findings and investigated the cases, finding 7 of 9 patients with idiopathic agranulocytosis had recent exposure to cocaine. None of the 21 total patients experienced any skin findings. Nausea and vomiting were common symptoms, but abdominal pain was described in only 2 patients from an additional investigation in Washington. Both of these patients used crack cocaine, and one had a positive urine test for levamisole.9

The presence of levamisole initially was detected by the US Drug Enforcement Administration in 2003. By July 2009, 69% of cocaine and 3% of heroin seized by this agency was noted to contain levamisole.16 From 2003 to 2009, the concentration of levamisole contamination rose to 10%.4 A 2011 study found levamisole in 194 of 249 cocaine-positive urine samples.16

It is unclear why cocaine producers add levamisoleto their product. Possibilities include increasing the drug’s bulk or enhancing its stimulatory effects.12 Chang et al17 posited that levamisole increases the stimulatory and euphoric effects of cocaine by increasing dopamine levels in the brain. Additionally, levamisole is metabolized to aminorex, an amphetaminelike hallucinogen that suppresses appetite, in patients with LCC.13 Vagi et al12 interviewed 10 patients who had been hospitalized for agranulocytosis secondary to use of LCC. None were aware of the presence of this additive, suggesting it was not used as a marketing tool.

Cutaneous Vasculopathy

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy (also called levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy11) initially was reported by 2 separate groups in 2010.1,2 Patients typically present with tender purpuric to hemorrhagic papules, plaques, and bullae with an affinity to affect the ears, nose, and face, though other areas of the body can be affected. A pattern of retiform purpura may precede these findings in some patients. Women are disproportionately affected.11 Crack cocaine use is overrepresented in LIV compared to insufflation or snorting of the drug. Affected patients may exhibit systemic symptoms including myalgia, arthralgia, and frank arthritis.10 Additionally, 15% to 80% of patients exhibit positive antinuclear antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant antibodies, p-ANCA antibodies, and c-ANCA antibodies. Magro and Wang8 hypothesized that levamisole acting in conjunction with cocaine rather than the effects of levamisole alone is responsible for some of these findings.

Histologically, the features of a vasculopathic process are noted in some patients with the presence of frank vasculitis.1 The vasculopathic component demonstrates vessel dilatation with thrombosis, eosinophilic deposits, and erythrocyte extravasation. Patients with frank vasculitis exhibit fibrinoid vessel wall necrosis and fibrin deposition, extravasated erythrocytes, endothelial cell atypia, and leukocytoclasia.3 Jacob et al3 noted interstitial and perivascular neovascularization in affected tissue, believed to represent one stage in the evolution of medium vessel vasculitis. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 has been reported in affected vessel walls with endothelial caspase 3 expression and C5b-9 deposition.8 Magro and Wang8 believe the retiform purpura seen in the early stages of some of these patients with LIV represents a thrombotic dynamic with C5b-9 deposition and enhanced apoptosis. Overt vasculitis follows later, subsequent to the effect of ANCA antibodies and upregulated intercellular adhesion molecule 1 expression on vessel walls.

The clinical course of LIV typically is 2 to 3 weeks for lesion resolution; however, normalization of serologies may require 2 to 14 months. Observation and pain control with or without administration of systemic steroids is sufficient for most patients, but skin grafting, wound debridement, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and plasmapheresis also have been employed.4,5 Morbidity may be substantive. One report noted LCC to be responsible for 3 cases of pulmonary hemorrhage and acute progression to chronic renal failure in another 2 patients.15 Ching and Smith18 described a patient with 52% total body surface area involvement who required skin grafting, nasal amputation, patellectomy, central upper lip excision, and amputation of the leg above the knee.

Gastrointestinal Presentation

Patients with LIV have been reported to exhibit abdominal pain, but our patient exhibited a rare presentation of visualized gastrointestinal purpura. Although support for a vasculitic/vasculopathic process requires a tissue diagnosis, the endoscopic appearance of gastric vasculitis is similar to that of cutaneous vasculitis.19 Clinicians caring for patients exposed to LCC should bear in mind that the vascular insults associated with LIV are not restricted solely to the skin.

In 2010, two separate reports of cutaneous vasculitic/vasculopathic eruptions in patients with recent exposure to levamisole-contaminated cocaine (LCC) were published in the literature.1,2 Since then, additional reports have been published.3-6 Retiform purpura associated with cocaine use appears to be a similar condition, perhaps lying at one end of the spectrum of LCC-induced cutaneous vascular disease.7,8 Although some patients have been described as having nausea and vomiting,8,9 including one with a sudden drop in hemoglobin to 5.8 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL),10 there are no known reported cases of LCC and levamisole-induced vasculopathy in organ systems other than the skin. Herein, we report the case of a patient with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV) demonstrating endoscopic evidence of gastric hemorrhage with features similar to those involving the skin.

Case Report

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C, intravenous drug abuse, and bipolar disorder presented to the emergency department with painful necrotic lesions on the head, neck, arms, and legs of several days’ duration. Approximately 1 year prior she had been admitted to the hospital with similar lesions, with eventual partial necrosis of the left earlobe. The patient reported she had last used crack cocaine 3 days prior to the development of the lesions. A urine drug screen was positive for lorazepam, alprazolam, buprenorphine, methadone, tetrahydrocannabinol, and cocaine. She also reported abdominal pain and gastric reflux of recent onset but denied any history of gastrointestinal tract disease. During the previous admission, the patient demonstrated antinuclear antibodies at a titer of greater than 1:160 (normal, <1:40) in a smooth pattern as well as positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) and cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA) and positive cryoglobulins. Physical examination yielded purpuric and hemorrhagic patches and plaques on the nose, bilateral ears (Figure 1A), face (Figure 1B), arms, and legs. Older lesions exhibited evidence of evolving erosion and ulceration. A biopsy of a lesion on the right arm was obtained, demonstrating extensive epidermal necrosis, hemorrhage, fibrin thrombi within dermal blood vessels, fibrinoid mural necrosis, perivascular neutrophils, and leukocytoclasis (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with LIV caused by exposure to LCC. A complete blood cell count was unremarkable. She was started on pain management and was given prednisone to treat the cutaneous eruption. Because of continued reports of epigastric pain and discomfort on swallowing, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed. Numerous esophageal erosions and gastric submucosal hemorrhages similar to those on the skin were noted (Figure 3). Pathology taken at the time of the endoscopy demonstrated mucosal erosions, but an evaluation for vascular insult was not possible, as submucosal tissue was not obtained. As the skin lesions began to heal, the gastric symptoms gradually subsided, and the patient was released from the hospital after 7 days.

Comment

Levamisole-Contaminated Cocaine

Cocaine is a crystalline alkaloid obtained from the leaves of the coca plant.7 Fifty percent of globally produced cocaine is consumed in the United States.10 There are 2 to 5 million cocaine users in the United States; in 2009, a reported 1.6 million US adults admitted to having used cocaine in the previous month.4,11,12 Cocaine has been known to be cut with similar-appearing substances including lactose and mannitol, though caffeine, acetaminophen, methylphenidate, and other ingredients have been utilized.7

Levamisole is a synthetic imidazothiazole derivative initially developed for use as an immunomodulatory agent in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.4 It was later paired with 5-fluorouracil for administration in patients with carcinomas of the colon and breasts.4,13 In 2000, the drug was withdrawn from the US market for use in humans after an association between levamisole and agranulocytosis was noted in 2.5% to 13% of patients taking the drug for rheumatoid arthritis or as an adjuvant therapy for breast carcinoma.9,12 It still is available for veterinary use as an anthelmintic and is administered to humans in other countries. Levamisole acts as an immunomodulator by enhancing macrophage chemotaxis and upregulating T-cell functions as well as stimulating neutrophil chemotaxis and dendritic cell maturation.4 It also is known to generate autoantibodies including lupus anticoagulant, p-ANCA, c-ANCA, and antinuclear antibodies.7,14 Levamisole is known to exhibit cutaneous reactions. In 1999, Rongioletti et al14 reported 5 children with purpura of the ears who had been given levamisole for pediatric nephrotic syndrome. Involvement of other body areas was noted. Three patients developed lupus anticoagulant antibodies, 3 exhibited p-ANCA antibodies, and 1 was positive for c-ANCA antibodies. The investigators noted an exceptionally long latency period of 12 to 44 months after starting the drug. Histologically a vasculopathic/vasculitic process was noted.14 Direct immunofluorescence studies of affected skin in LIV have demonstrated IgM, IgA, IgG, C3, and fibrin staining of blood vessels.4,15 Anti–human elastase antibodies are considered both sensitive and specific for LIV and serve to differentiate it from cocaine-induced pseudovasculitis.4,7

In April 2008, the New Mexico Department of Health began evaluating several unexplained cases of agranulocytosis and noted that 11 of 21 cases were associated with cocaine use.9 Later that year, public health workers in Alberta and British Columbia, Canada, reported finding traces of levamisole in clinical specimens and drug paraphernalia of cocaine users with agranulocytosis. Officials from the New Mexico Department of Health learned of these findings and investigated the cases, finding 7 of 9 patients with idiopathic agranulocytosis had recent exposure to cocaine. None of the 21 total patients experienced any skin findings. Nausea and vomiting were common symptoms, but abdominal pain was described in only 2 patients from an additional investigation in Washington. Both of these patients used crack cocaine, and one had a positive urine test for levamisole.9

The presence of levamisole initially was detected by the US Drug Enforcement Administration in 2003. By July 2009, 69% of cocaine and 3% of heroin seized by this agency was noted to contain levamisole.16 From 2003 to 2009, the concentration of levamisole contamination rose to 10%.4 A 2011 study found levamisole in 194 of 249 cocaine-positive urine samples.16

It is unclear why cocaine producers add levamisoleto their product. Possibilities include increasing the drug’s bulk or enhancing its stimulatory effects.12 Chang et al17 posited that levamisole increases the stimulatory and euphoric effects of cocaine by increasing dopamine levels in the brain. Additionally, levamisole is metabolized to aminorex, an amphetaminelike hallucinogen that suppresses appetite, in patients with LCC.13 Vagi et al12 interviewed 10 patients who had been hospitalized for agranulocytosis secondary to use of LCC. None were aware of the presence of this additive, suggesting it was not used as a marketing tool.

Cutaneous Vasculopathy

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy (also called levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy11) initially was reported by 2 separate groups in 2010.1,2 Patients typically present with tender purpuric to hemorrhagic papules, plaques, and bullae with an affinity to affect the ears, nose, and face, though other areas of the body can be affected. A pattern of retiform purpura may precede these findings in some patients. Women are disproportionately affected.11 Crack cocaine use is overrepresented in LIV compared to insufflation or snorting of the drug. Affected patients may exhibit systemic symptoms including myalgia, arthralgia, and frank arthritis.10 Additionally, 15% to 80% of patients exhibit positive antinuclear antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant antibodies, p-ANCA antibodies, and c-ANCA antibodies. Magro and Wang8 hypothesized that levamisole acting in conjunction with cocaine rather than the effects of levamisole alone is responsible for some of these findings.

Histologically, the features of a vasculopathic process are noted in some patients with the presence of frank vasculitis.1 The vasculopathic component demonstrates vessel dilatation with thrombosis, eosinophilic deposits, and erythrocyte extravasation. Patients with frank vasculitis exhibit fibrinoid vessel wall necrosis and fibrin deposition, extravasated erythrocytes, endothelial cell atypia, and leukocytoclasia.3 Jacob et al3 noted interstitial and perivascular neovascularization in affected tissue, believed to represent one stage in the evolution of medium vessel vasculitis. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 has been reported in affected vessel walls with endothelial caspase 3 expression and C5b-9 deposition.8 Magro and Wang8 believe the retiform purpura seen in the early stages of some of these patients with LIV represents a thrombotic dynamic with C5b-9 deposition and enhanced apoptosis. Overt vasculitis follows later, subsequent to the effect of ANCA antibodies and upregulated intercellular adhesion molecule 1 expression on vessel walls.

The clinical course of LIV typically is 2 to 3 weeks for lesion resolution; however, normalization of serologies may require 2 to 14 months. Observation and pain control with or without administration of systemic steroids is sufficient for most patients, but skin grafting, wound debridement, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and plasmapheresis also have been employed.4,5 Morbidity may be substantive. One report noted LCC to be responsible for 3 cases of pulmonary hemorrhage and acute progression to chronic renal failure in another 2 patients.15 Ching and Smith18 described a patient with 52% total body surface area involvement who required skin grafting, nasal amputation, patellectomy, central upper lip excision, and amputation of the leg above the knee.

Gastrointestinal Presentation

Patients with LIV have been reported to exhibit abdominal pain, but our patient exhibited a rare presentation of visualized gastrointestinal purpura. Although support for a vasculitic/vasculopathic process requires a tissue diagnosis, the endoscopic appearance of gastric vasculitis is similar to that of cutaneous vasculitis.19 Clinicians caring for patients exposed to LCC should bear in mind that the vascular insults associated with LIV are not restricted solely to the skin.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Bradford M, Rosenberg B, Moreno J, et al. Bilateral necrosis of earlobes and cheeks: another complication of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. Ann Int Med. 2010;152:758-759.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Lee KC, Ladizinski B, Federman DG. Complications associated with use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine: an emerging public health challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:581-586.

- Pavenski K, Vandenberghe H, Jakubovic H, et al. Plasmapheresis and steroid treatment of levamisole-induced vasculopathy and associated skin necrosis in crack/cocaine users. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:123-126.

- Mandrell J, Kranc CL. Prednisone and vardenafil hydrochloride refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Cutis. 2016;98:E15-E19.

- Walsh NM, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole [published online August 25, 2010]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Magro CM, Wang X. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura: a C5b-9 mediated microangiopathy syndrome associated with enhanced apoptosis and high levels of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression. Am J Dermatopathol 2013;35:722-730.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Agranulocytosis associated with cocaine use—four states, March 2008-November 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1381-1385.

- Espinoza LR, Alamino RP. Cocaine-induced vasculitis: clinical and immunological spectrum. Curr Rhematol Rep. 2012;14:532-538.

- Arora NP. Cutaneous vasculopathy and neutropenia associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345:45-51.

- Vagi SJ, Sheikh S, Brackney M, et al. Passive multistate surveillance for neutropenia after of cocaine or heroin possibly contaminated with levamisole. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:468-474.

- Lee KC, Ladizinski, Nutan FN. Systemic complications of levamisole toxicity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:791-792.

- Rongioletti E, Ghio L, Ginervri E, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating longer-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- McGrath MM, Isakova T, Rennke HG, et al. Contaminated cocaine and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2799-2805.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Chang A, Osterloh J, Thomas J. Levamisole: a dangerous new cocaine adulterant. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:408-411.

- Ching JA, Smith DJ. Levamisole-induced necrosis of skin, soft-tissue and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:E1-E5.

- Naruse G, Shimata K. Cutaneous and gastrointestinal purpura. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1843.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Bradford M, Rosenberg B, Moreno J, et al. Bilateral necrosis of earlobes and cheeks: another complication of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. Ann Int Med. 2010;152:758-759.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Lee KC, Ladizinski B, Federman DG. Complications associated with use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine: an emerging public health challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:581-586.

- Pavenski K, Vandenberghe H, Jakubovic H, et al. Plasmapheresis and steroid treatment of levamisole-induced vasculopathy and associated skin necrosis in crack/cocaine users. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:123-126.

- Mandrell J, Kranc CL. Prednisone and vardenafil hydrochloride refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Cutis. 2016;98:E15-E19.

- Walsh NM, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole [published online August 25, 2010]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Magro CM, Wang X. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura: a C5b-9 mediated microangiopathy syndrome associated with enhanced apoptosis and high levels of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression. Am J Dermatopathol 2013;35:722-730.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Agranulocytosis associated with cocaine use—four states, March 2008-November 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1381-1385.

- Espinoza LR, Alamino RP. Cocaine-induced vasculitis: clinical and immunological spectrum. Curr Rhematol Rep. 2012;14:532-538.

- Arora NP. Cutaneous vasculopathy and neutropenia associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345:45-51.

- Vagi SJ, Sheikh S, Brackney M, et al. Passive multistate surveillance for neutropenia after of cocaine or heroin possibly contaminated with levamisole. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:468-474.

- Lee KC, Ladizinski, Nutan FN. Systemic complications of levamisole toxicity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:791-792.

- Rongioletti E, Ghio L, Ginervri E, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating longer-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- McGrath MM, Isakova T, Rennke HG, et al. Contaminated cocaine and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2799-2805.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Chang A, Osterloh J, Thomas J. Levamisole: a dangerous new cocaine adulterant. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:408-411.

- Ching JA, Smith DJ. Levamisole-induced necrosis of skin, soft-tissue and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:E1-E5.

- Naruse G, Shimata K. Cutaneous and gastrointestinal purpura. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1843.

Practice Points

- More than half of the cocaine illicitly consumed in the United States is contaminated with levamisole, a veterinary drug that can incite a vasculitic/vasculopathic response in the skin as well as in other organ systems.

- Because dermatologists often are the specialists to make the diagnosis of levamisole-induced vasculopathy, clinicians should be made aware that consumption of levamisole-contaminated cocaine may affect more than the skin alone.