Sea cucumbers—commonly known as trepang in Indonesia, namako in Japan, and hai shen in China, where they are treasured as a food delicacy—are sea creatures belonging to the phylum Echinodermata, class Holothuridea, and family Cucumariidae . 1,2 They are an integral part of a variety of marine habitats, serving as cleaners as they filter through sediment for nutrients. They can be found on the ocean floor under hundreds of feet of water or in shallow sandy waters along the coast, but they most commonly are found living among coral reefs. Sea cucumbers look just as they sound—shaped like cucumbers or sausages, ranging from under 1 inch to upwards of 6 feet in length depending on the specific species (Figure 1). They have a group of tentacles around the mouth used for filtering sediment, and they move about the ocean floor on tubular feet protruding through the body wall, similar to a sea star.

Beneficial Properties and Cultural Relevance

Although more than 1200 species of sea cucumbers have been identified thus far, only about 20 of these are edible.2 The most common of the edible species is Stichopus japonicus, which can be found off the coasts of Korea, China, Japan, and Russia. This particular species most commonly is used in traditional dishes and is divided into 3 groups based on the color: red, green, or black. The price and taste of sea cucumbers varies based on the color, with red being the most expensive.2 The body wall of the sea cucumber is cleaned, repeatedly boiled, and dried until edible. It is considered a delicacy, not only in food but also in pharmaceutical forms, as it is comprised of a variety of vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients that are thought to provide anticancer, anticoagulant, antioxidant, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory properties. Components of the body wall include collagen, mucopolysaccharides, peptides, gelatin, glycosaminoglycans, glycosides (including various holotoxins), hydroxylates, saponins, and fatty acids.2 The regenerative properties of the sea cucumber also are important in future biomedical developments.

Toxic Properties

Although sea cucumbers have proven to have many beneficial properties, at least 30 species also produce potent toxins that pose a danger to both humans and other wildlife.3 The toxins are collectively referred to as holothurin; however, specific species actually produce a variety of holothurin toxins with unique chemical structures. Each toxin is a variation of a specific triterpene glycoside called saponins, which are common glycosides in the plant world. Holothurin was the first saponin to be found in animals. The only animals known to contain holothurin are the echinoderms, including sea cucumbers and sea stars.1 Holothurins A and B are the 2 groups of holothurin toxins produced specifically by sea cucumbers. The toxins are composed of roughly 60% glycosides and pigment; 30% free amino acids (alanine, arginine, cysteine, glycine, glutamic acid, histidine, serine, and valine); 5% to 10% insoluble proteins; and 1% cholesterol, salts, and polypeptides.3

Holothurins are concentrated in granules within specialized structures of the sea cucumber called Cuvierian tubules, which freely float in the posterior coelomic cavity of the sea cucumber and are attached at the base of the respiratory tree. It is with these tubules that sea cucumbers utilize a unique defensive mechanism. Upon disturbance, the sea cucumber will turn its posterior end to the threat and squeeze its body in a series of violent contractions, inducing a tear in the cloacal wall.4 The tubules pass through this tear, are autotomized from the attachment point at the respiratory tree, and are finally expelled through the anus onto the predator and into the surrounding waters. The tubules are both sticky on contact and poisonous due to the holothurin, allowing the sea cucumber to crawl away from the threat unscathed. Over time, the tubules will regenerate, allowing the sea cucumber to protect itself again in the face of future danger.

Aside from direct disturbance by a threat, sea cucumbers also are known to undergo evisceration due to high temperatures and oxygen deficiency.3 Species that lack Cuvierian tubules can still produce holothurin toxins, though the toxins are secreted onto the outer surface of the body wall and mainly pose a risk with direct contact undiluted by seawater.5 The toxin induces a neural blockade in other sea creatures through its interaction with ion channels. On Asian islands, sea cucumbers have been exploited for this ability and commonly are thrown into tidal pools by fishermen to paralyze fish for easier capture.1

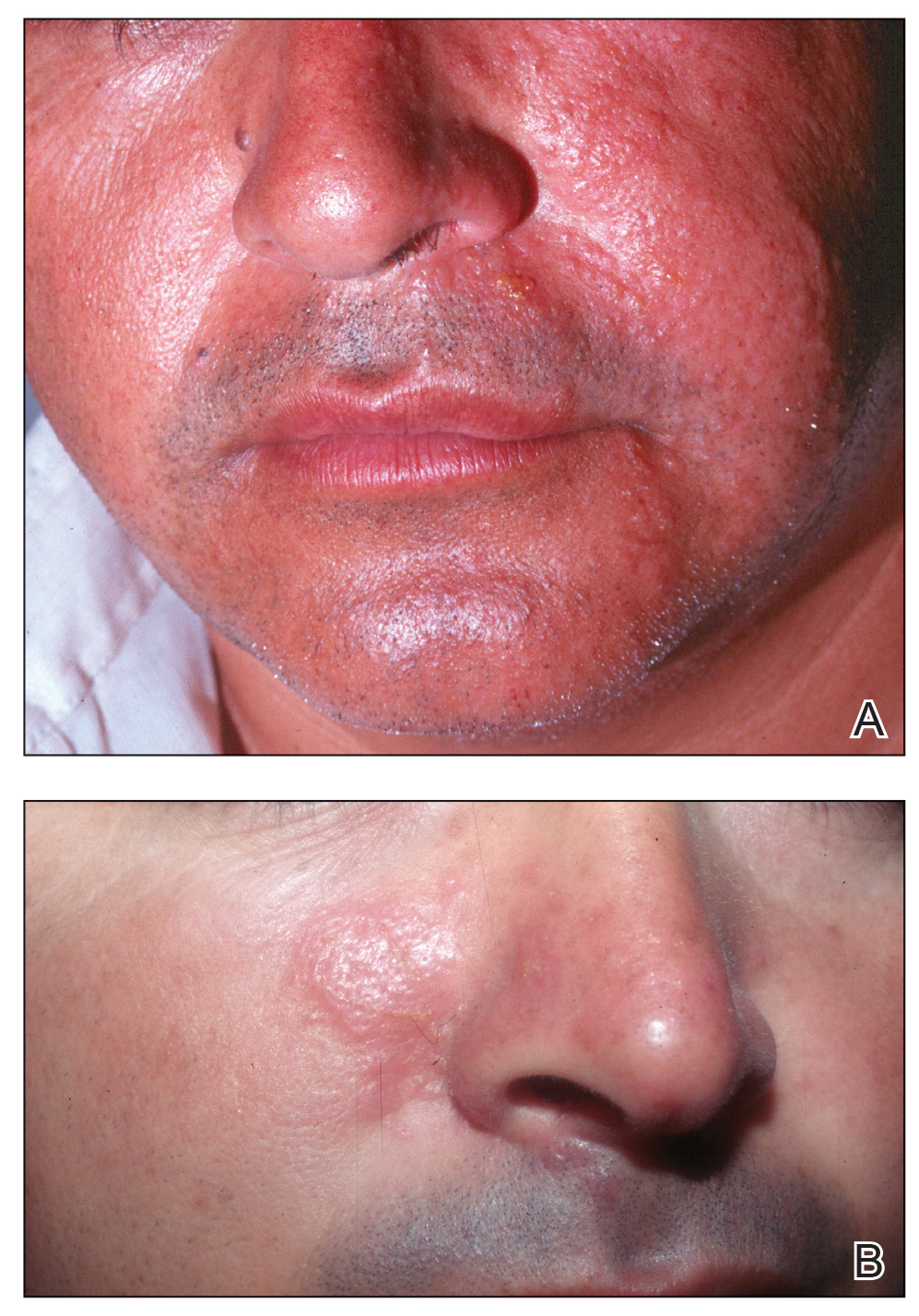

Effects on Human Skin

In humans, the holothurin toxins of sea cucumbers cause an acute irritant dermatitis upon contact with the skin.6 Fishermen or divers handling sea cucumbers without gloves may present with an irritant contact dermatitis characterized by marked erythema and swelling (Figure 2).6-8 Additionally, holothurin toxins can cause irritation of the mucous membranes of the eyes and mouth. Contact with the mucous membranes of the eyes can induce a painful conjunctivitis that may result in blindness.6,8 Ingestion of large quantities of sea cucumber can produce an anticoagulant effect, and toxins in some species act similar to cardiac glycosides.3,9