Causes of Lepidopterism

Caterpillars are wormlike organisms that serve as the larval stage of moths and butterflies, which belong to the order Lepidoptera. There are almost 165,000 discovered species, with 13,000 found in the United States.1,2 Roughly 150 species are known to have the potential to cause an adverse reaction in humans, with 50 of these in the United States.1Lepidopterism describes systemic and cutaneous reactions to moths, butterflies, and caterpillars; erucism describes strictly cutaneous reactions.1

Although the rate of lepidopterism is thought to be underreported because it often is self-limited and of a mild nature, a review found caterpillars to be the cause of roughly 2.2% of reported bites and stings annually.2 Cases increase in number with seasonal increases in caterpillars, which vary by region and species. For example, the Megalopyge opercularis (southern flannel moth) caterpillar was noted to have 2 peaks in a Texas-based study: 12% of reported stings occurred in July; 59% from October through November.3 In general, the likelihood of exposure increases during warmer months, and exposure is more common in people who work outdoors in a rural area or in a suburban area where there are many caterpillar-infested trees.4

Most cases of lepidopterism are caused by caterpillars, not by adult butterflies and moths, because the former have many tubular, or porous, hairlike structures called setae that are embedded in the integument. Setae were once thought to be connected to poison-secreting glandular cells, but current belief is that venomous caterpillars lack specialized gland cells and instead produce venom through secretory epithelial cells located above the integument.1 Venom accumulates in the hemolymph and is stored in the setae or other types of bristles, such as scoli (wartlike bumps that bear setae) or spines.5 With a large amount of chitin, bristles have a tendency to fracture and release venom upon contact.1 It is thought that some species of caterpillars formulate venom by ingesting toxins or toxin precursors from plants; for example, the tiger moth (family Arctiidae) is known to produce venom containing biogenic amines, pyrrolizidine, alkaloids, and cardiac glycosides obtained through food sources.5

Even if a caterpillar does not produce venom, its setae might embed into skin or mucous membranes and cause an adverse irritant reaction.1 Setae also might dislodge and be transported in the air to embed in objects—some remaining stable in the environment for longer than a year.2 In contrast to setae, spines are permanently fixed into the integument; for that reason, only direct contact with the caterpillar can result in an adverse reaction. Although it is mostly caterpillars that contain setae and spines, certain species of moths also might contain these structures or might acquire them as they emerge from the cocoon, which often contains incorporated setae.2

Reactions in Humans

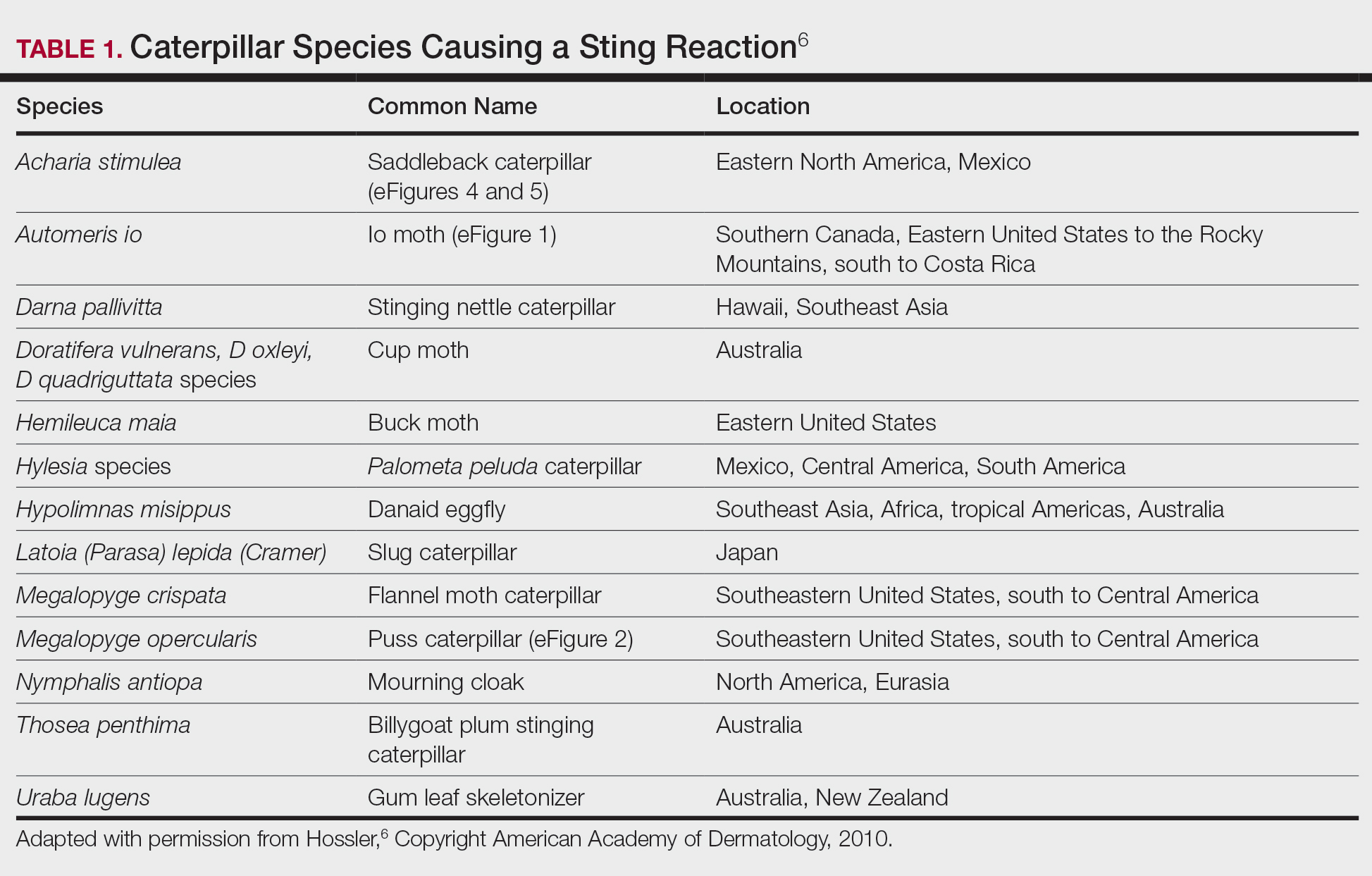

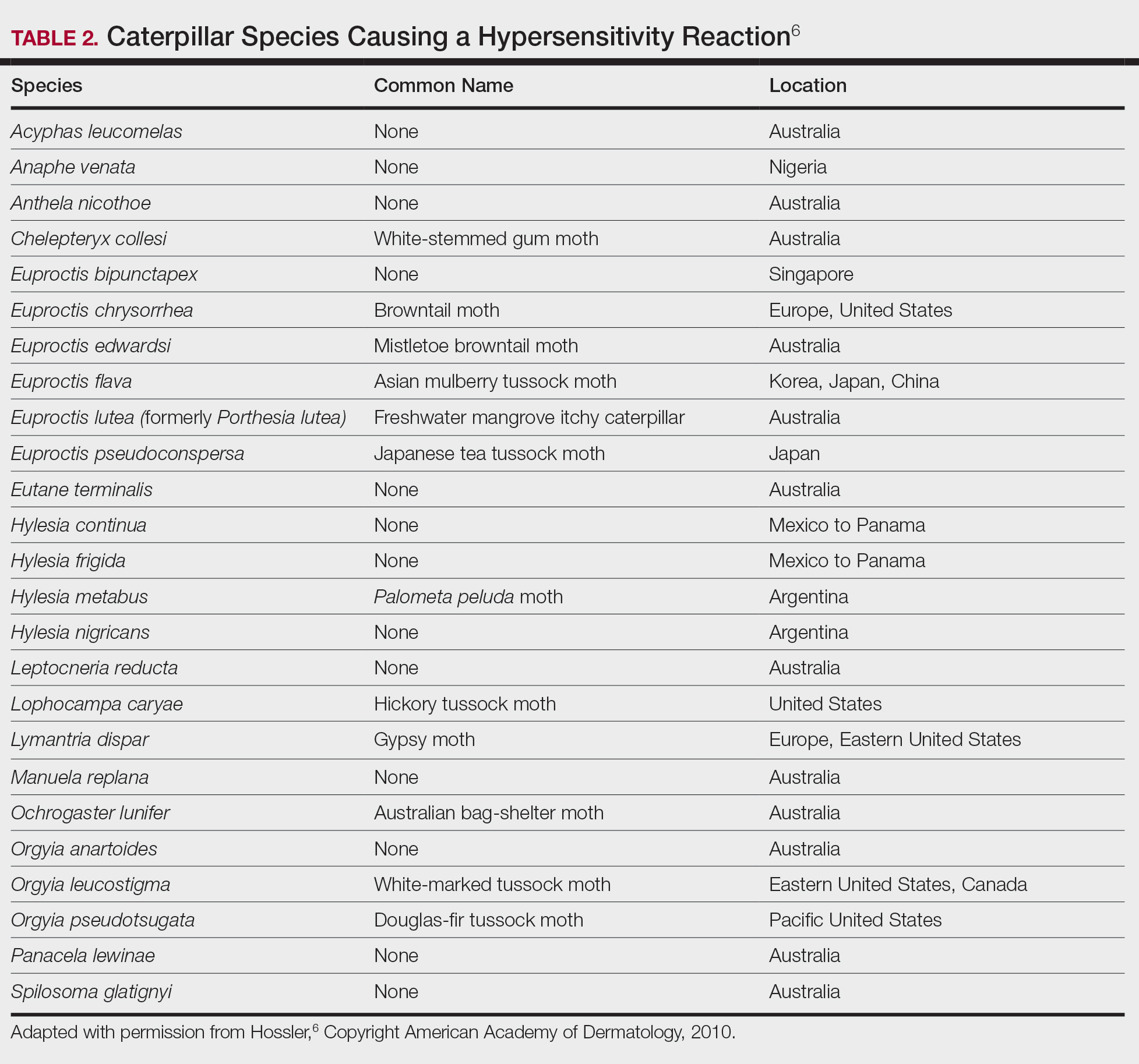

Lepidopterism encompasses 3 principal reactions in humans: sting reaction, hypersensitivity reaction, and lonomism (a hemorrhagic diathesis produced by Lonomia caterpillars). The type and severity of the reaction depends on (1) the species of caterpillar or moth and (2) the individual patient.2 There are approximately 12 families of caterpillars, mainly of the moth variety, that can cause an adverse reaction in humans.1 Tables 1 and 2 list examples of species that cause each type of reaction.6

Chemicals and toxins contained in the poison of setae and spines vary by species of caterpillar. Numerous kinds have been isolated from different venoms,1,2 including several peptides, histamine, histamine-releasing substances, acetylcholine, phospholipase A, hyaluronidase, formic acid, proteins with trypsinlike activity, serine proteases such as kallikrein, and other enzymes with vasodegenerative and fibrinolytic properties

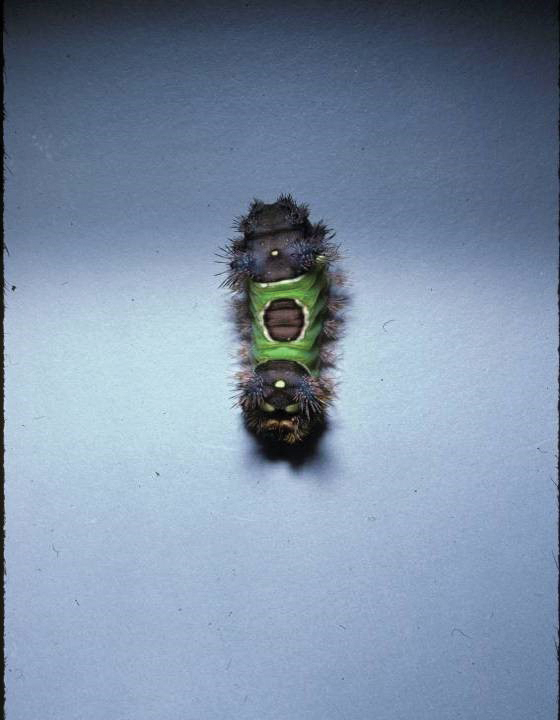

Stings: An Immediate Adverse Reaction—Depending on the venom, a sting might result in mild to severe burning pain, accompanied by welts, vesicles, and red papules or plaques.2 Figure 1 demonstrates a particularly mild sting from a caterpillar of the family Automeris, examples of which are seen in Figures 2 and 3 and eFigure 1. Components of the venom determine the mechanism of the sting and the pain that accompanies it. For example, a recent study demonstrated that the venom of the Latoia consocia caterpillar induces pain through the ion-channel receptor known as transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, which integrates and sends painful stimuli from the peripheral nervous system to the central nervous system.7 It is thought that a variety of ion channels are targets of the venom of caterpillars.