Photoallergic contact dermatitis (PACD), a subtype of allergic contact dermatitis that occurs because of the specific combination of exposure to an exogenous chemical applied topically to the skin and UV radiation, may be more common than was once thought.1 Although the incidence in the general population is unknown, current research points to approximately 20% to 40% of patients with suspected photosensitivity having a PACD diagnosis.2 Recently, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) reported that 21% of 373 patients undergoing photopatch testing (PPT) were diagnosed with PACD2; however, PPT is not routinely performed, which may contribute to underdiagnosis.

Mechanism of Disease

Similar to allergic contact dermatitis, PACD is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction; however, it only occurs when an exogenous chemical is applied topically to the skin with concomitant exposure to UV radiation, usually in the UVA range (315–400 nm).3,4 When exposed to UV radiation, it is thought that the exogenous chemical combines with a protein in the skin and transforms into a photoantigen. In the sensitization phase, the photoantigen is taken up by antigen-presenting cells in the epidermis and transported to local lymph nodes where antigen-specific T cells are generated.5 In the elicitation phase, the inflammatory reaction of PACD occurs upon subsequent exposure to the same chemical plus UV radiation.4 Development of PACD does not necessarily depend on the dose of the chemical or the amount of UV radiation.6 Why certain individuals may be more susceptible is unknown, though major histocompatibility complex haplotypes could be influential.7,8

Clinical Manifestations

Photoallergic contact dermatitis primarily presents in sun-exposed areas of the skin (eg, face, neck, V area of the chest, dorsal upper extremities) with sparing of naturally photoprotected sites, such as the upper eyelids and nasolabial and retroauricular folds. Other than its characteristic photodistribution, PACD often is clinically indistinguishable from routine allergic contact dermatitis. It manifests as a pruritic, poorly demarcated, eczematous or sometimes vesiculobullous eruption that develops in a delayed fashion—24 to 72 hours after sun exposure. The dermatitis may extend to other parts of the body either through spread of the chemical agent by the hands or clothing or due to the systemic nature of the immune response. The severity of the presentation can vary depending on multiple factors, such as concentration and absorption of the agent, length of exposure, intensity and duration of UV radiation exposure, and individual susceptibility.4 Chronic PACD may become lichenified. Generally, rashes resolve after discontinuation of the causative agent; however, long-term exposure may lead to development of chronic actinic dermatitis, with persistent photodistributed eczema regardless of contact with the initial inciting agent.9

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with photodistributed dermatitis is broad; therefore, taking a thorough history is important. Considerations include age of onset, timing and persistence of reactions, use of topical and systemic medications (both prescription and over-the-counter [OTC]), personal care products, occupation, and hobbies, as well as a thorough review of systems.

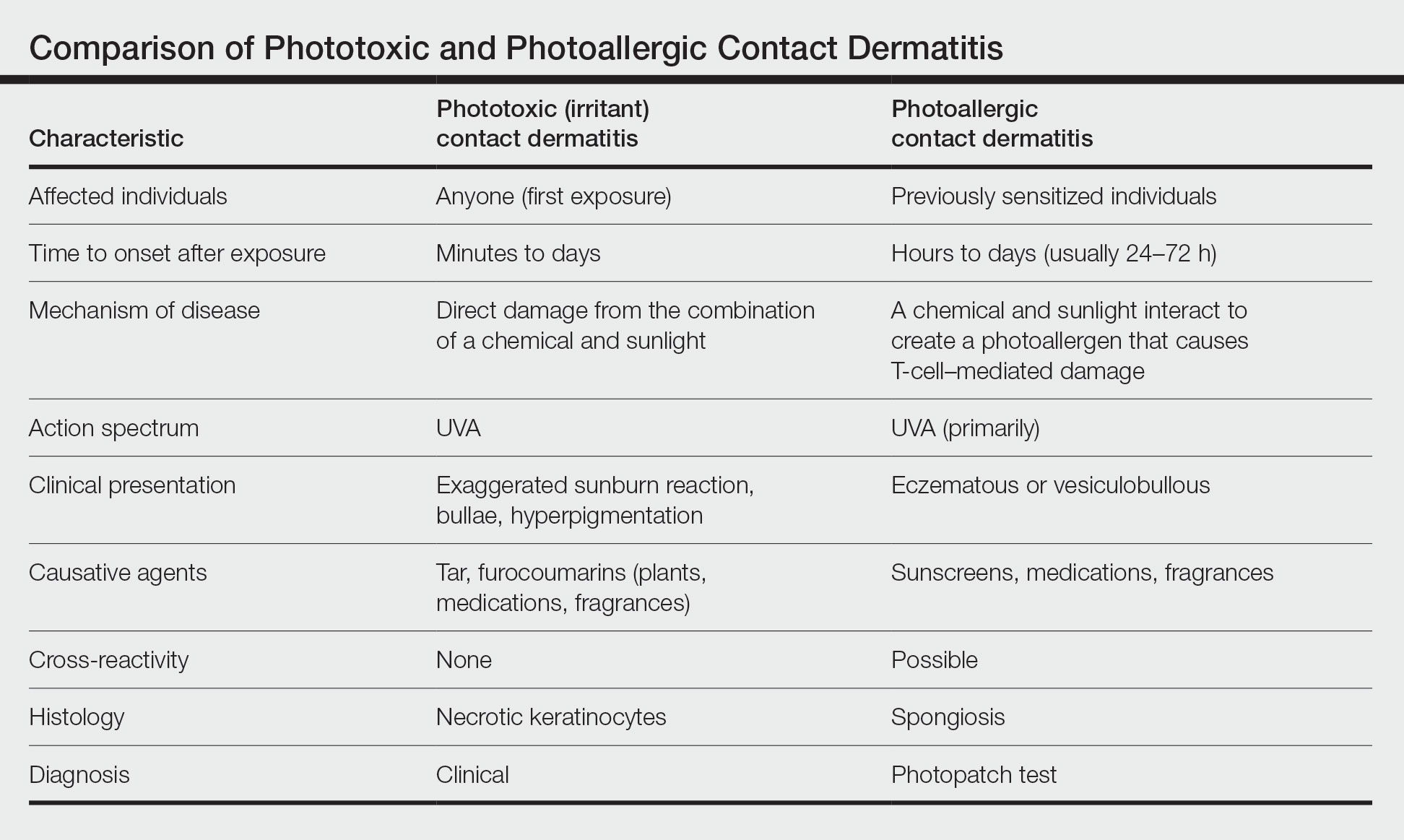

It is important to distinguish PACD from phototoxic contact dermatitis (PTCD)(also known as photoirritant contact dermatitis)(Table). Asking about the onset and timing of the eruption may be critical for distinction, as PTCD can occur within minutes to hours of the first exposure to a chemical and UV radiation, while there is a sensitization delay in PACD.6 Phytophotodermatitis is a well-known type of PTCD caused by exposure to furocoumarin-containing plants, most commonly limes.10 Other causes of PTCD include tar products and certain medications.11 Importantly, PPT to a known phototoxic chemical should never be performed because it will cause a strong reaction in anyone tested, regardless of exposure history.

Other diagnoses to consider include photoaggravated dermatoses (eg, atopic dermatitis, lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis) and idiopathic photodermatoses (eg, chronic actinic dermatitis, actinic prurigo, polymorphous light eruption). Although atopic dermatitis usually improves with UV light exposure, photoaggravated atopic dermatitis is suggested in eczema patients who flare with sun exposure, in a seasonal pattern, or after phototherapy; this condition is challenging to differentiate from PACD if PPT is not performed.12 The diagnosis of idiopathic photodermatoses is nuanced; however, asking about the timeline of the reaction including onset, duration, and persistence, as well as characterization of unique clinical features, can help in differentiation.13 In certain scenarios, a biopsy may be helpful. A thorough review of systems will help to assess for autoimmune connective tissue disorders, and relevant serologies should be checked as indicated.

Diagnosis

Histologically, PACD presents similarly to allergic contact dermatitis with spongiotic dermatitis; therefore, biopsy cannot be relied upon to make the diagnosis.6 Photopatch testing is required for definitive diagnosis. It is reasonable to perform PPT in any patient with chronic dermatitis primarily affecting sun-exposed areas without a clear alternative diagnosis.14,15 Of note, at present there are no North American consensus guidelines for PPT, but typically duplicate sets of photoallergens are applied to both sides of the patient’s back and one side is exposed to UVA radiation. The reactions are compared after 48 to 96 hours.15 A positive reaction only at the irradiated site is consistent with photoallergy, while a reaction of equal strength at both the irradiated and nonirradiated sites indicates regular contact allergy. The case of a reaction occurring at both sites with a stronger response at the irradiated site is known as photoaggravated contact allergy, which can be thought of as allergic contact dermatitis that worsens but does not solely occur with exposure to sunlight.