AMSTAR Ratings—After using AMSTAR-2 to appraise the included systematic reviews, we found that 6 (3.5%) of the 173 studies could be rated as high; 36 (20.8%) as moderate; 25 (14.5%) as low; and 106 (61.3%) as critically low. Of the 37 abstracts containing spin, 2 (5.4%) had an AMSTAR-2 rating of high, 10 (27%) had a rating of moderate, 6 (16.2%) had a rating of low, and 19 (51.4%) had a rating of critically low (Table 2). No statistically significant associations were seen between abstracts found to have spin and the AMSTAR-2 rating of the review.

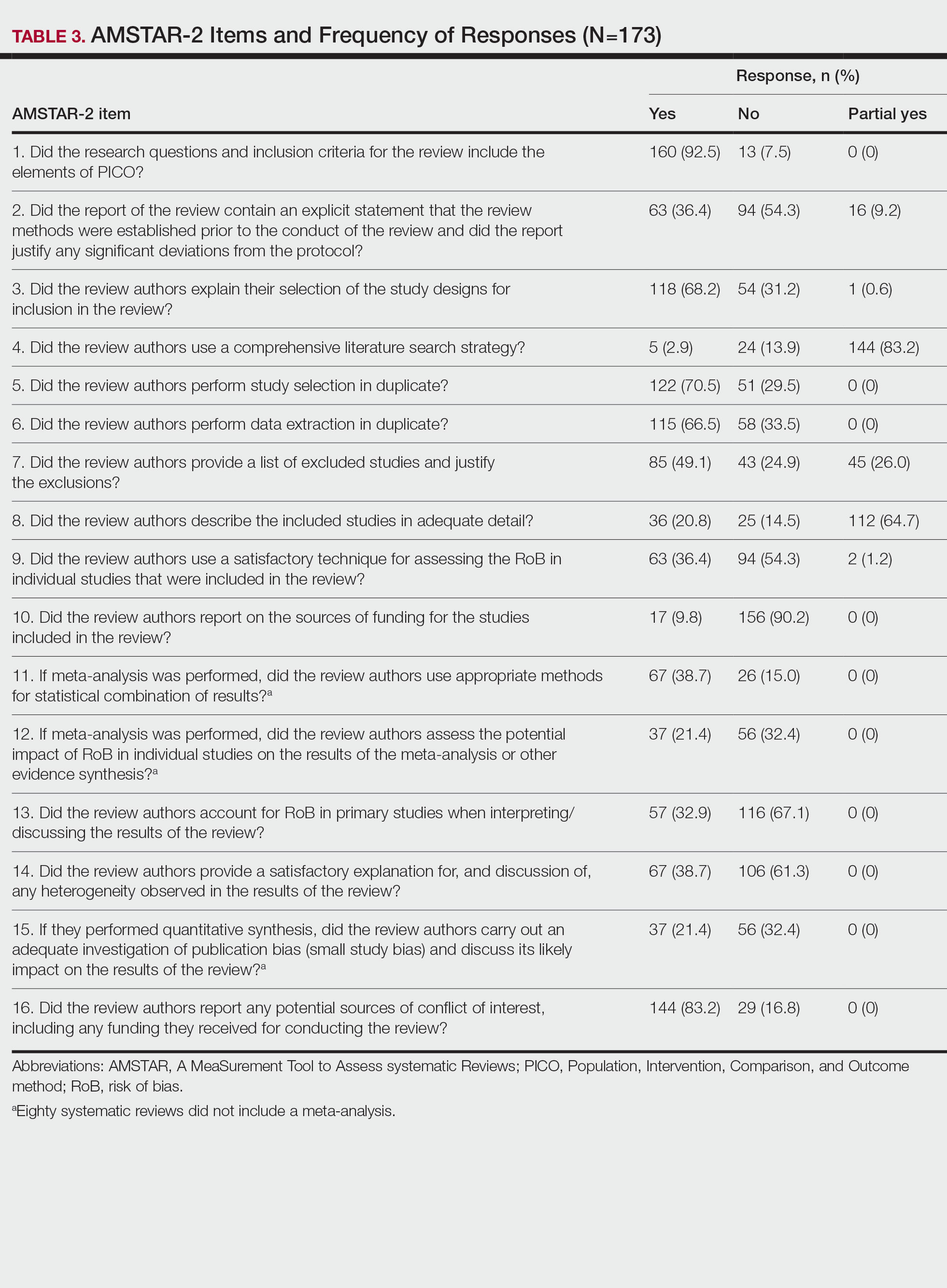

Nearly all (160/173 [92.5%]) of the included reviews were compliant with the inclusion of Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) method. Only 17 of 173 (9.8%) reviews reported funding sources for the studies included. See Table 3 for all AMSTAR-2 items.

Comment

Primary Findings—We evaluated the abstracts of systematic reviews for the treatment of psoriasis and found that more than one-fifth of them contained spin. Our study contributes to the existing literature surrounding spin. Spin in randomized controlled trials is well documented across several fields of medicine, including otolaryngology,10 obesity medicine,12 dermatology,21 anesthesiology,22 psychiatry,23 orthopedics,24 emergency medicine,25 oncology,26 and cardiology.27 More recently, studies have emerged evaluating the presence of spin in systematic reviews. Specific to dermatology, one study found that 74% (84/113) of systematic reviews related to atopic dermatitis treatment contained spin.28 Additionally, Ottwell et al13 identified spin in 31% (11/36) of the systematic reviews related to the treatment of acne vulgaris, which is similar to our results for systematic reviews focused on psoriasis treatments. When comparing the presence of spin in abstracts of systematic reviews from the field of dermatology with other specialties, dermatology-focused systematic reviews appear to contain more spin in the abstract than systematic reviews focused on tinnitus and glaucoma therapies.29,30 However, systematic reviews from the field of dermatology appear to contain less spin than systematic reviews focused on therapies for lower back pain.31 For example, Nascimento et al31 found that 80% (53/66) of systematic reviews focused on low-back pain treatments contained spin.

Examples of Spin—The most common type of spin found in our study was type 6.9 An example of spin type 6 can be found in an article by Bai et al32 that investigated the short-term efficacy and safety of multiple interleukin inhibitors for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. The conclusion of the abstract states, “Risankizumab appeared to have relatively high efficacy and low risk.” However, in the results section, the authors showed that risankizumab had the highest risk of serious adverse events and was ranked highest for discontinuation because of adverse events when compared with other interleukin inhibitors. Here, the presence of spin in the abstract may mislead the reader to accept the “low risk” of risankizumab without understanding the study’s full results.32

Another example of selective reporting of harm outcomes in a systematic review can be found in the article by Wu et al,33 which focused on assessing IL-17 antagonists for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. The conclusion of the abstract indicated that IL-17 antagonists should be accepted as safe; however, in the results section, the authors discussed serious safety concerns with brodalumab, including the death of 4 patients from suicide.33 This example of spin type 6 highlights how the overgeneralization of a drug’s safety profile neglects serious harm outcomes that are critical to patient safety. In fact, against the safety claims of Wu et al,33 brodalumab later received a boxed warning from the US Food and Drug Administration after 6 patients died from suicide while receiving the drug, which led to early discontinuation of the trials.34,35 Although studies suggest this relationship is not causal,34-36 the purpose of our study was not to investigate this association but to highlight the importance of this finding. Thus, with this example of spin in mind, we offer recommendations that we believe will improve reporting in abstracts as well as quality of patient care.

Recommendations for Reporting in Abstracts—Regarding the boxed warning37 for brodalumab because of suicidal ideation and behavior, the US Food and Drug Administration recommends that prior to prescribing brodalumab, clinicians consider the potential benefits and risks in patients with a history of depression and/or suicidal ideation or behavior. However, a clinician would not adequately assess the full risks and benefits when an abstract, such as that for the article by Wu et al,33 contains spin through selectively reporting harm outcomes. Arguably, clinicians could just read the full text; however, research confirms that abstracts often are utilized by clinicians and commonly are used to guide clinical decisions.7,38 It is reasonable that clinicians would use abstracts in this fashion because they provide a quick synopsis of the full article’s findings and are widely available to clinicians who may not have access to article databases. Initiatives are in place to improve the quality of reporting in an abstract, such as PRISMA-A,20 but even this fails to address spin. In fact, it may suggest spin because checklist item 10 of PRISMA-A advises authors of systematic reviews to provide a “general interpretation of the results and important implications.” This item is concerning because it suggests that the authors interpret importance rather than the clinician who prescribes the drug and is ultimately responsible for patient safety. Therefore, we recommend a reform to abstract reporting and an update to PRISMA-A that leads authors to report all benefits and risks encountered instead of reporting what the authors define as important.

Strengths and Limitations—Our study has several strengths as well as limitations. One of these strengths is that our protocol was strictly adhered to; any deviations were noted and added as an amendment. Our protocol, data, and all study artifacts were made freely available online on the Open Science Framework to strengthen reproducibility (https://osf.io/zrxh8/). Investigators underwent training to ensure comprehension of spin and systematic review designs. All data were extracted in masked duplicate fashion per the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.39

Regarding limitations, only 2 databases were searched—MEDLINE and Embase. Therefore, our screening process may not have included every available systematic review on the treatment of psoriasis. Journal impact factors may be inaccurate for the systematic reviews that were published earlier in our data date range; however, we attempted to negate this limitation by using a 5-year average. Our study characteristic regarding PRISMA adherence did not account for studies published before the PRISMA statement release; we also could not access prior submission guidelines to determine when a journal began recommending PRISMA adherence. Another limitation of our study was the intrinsic subjectivity behind spin. Some may disagree with our classifications. Finally, our cross-sectional design should not be generalized to study types that are not systematic reviews or published in other journals during different periods.

Conclusion

Evidence of spin was present in many of the abstracts of systematic reviews pertaining to the treatment of psoriasis. Future clinical research should investigate any reporting of spin and search for ways to better reduce spin within literature. Continued research is necessary to evaluate the presence of spin within dermatology and other specialties.