The genus Leishmania comprises protozoan parasites that cause approximately 2 million new cases of leishmaniasis each year across 98 countries.1 These protozoa are obligate intracellular parasites of phlebotomine sandfly species that transmit leishmaniasis and result in a considerable parasitic cause of fatalities globally, second only to malaria.2,3

Phlebotomine sandflies primarily live in tropical and subtropical regions and function as vectors for many pathogens in addition to Leishmania species, such as Bartonella species and arboviruses.3 In 2004, it was noted that the majority of leishmaniasis cases affected developing countries: 90% of visceral leishmaniasis cases occurred in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil, and 90% of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases occurred in Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Iran, Peru, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.4 Of note, with recent environmental changes, phlebotomine sandflies have gradually migrated to more northerly latitudes, extending into Europe.5

Twenty Leishmania species and 30 sandfly species have been identified as causes of leishmaniasis.4 Leishmania infection occurs when an infected sandfly bites a mammalian host and transmits the parasite’s flagellated form, known as a promastigote. Host inflammatory cells, such as monocytes and dendritic cells, phagocytize parasites that enter the skin. The interaction between parasites and dendritic cells become an important factor in the outcome of Leishmania infection in the host because dendritic cells promote development of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes with specificity to target Leishmania parasites and protect the host.1

The number of cases of leishmaniasis has increased worldwide, most likely due to changes in the environment and human behaviors such as urbanization, the creation of new settlements, and migration from rural to urban areas.3,5 Important risk factors in individual patients include malnutrition; low-quality housing and sanitation; a history of migration or travel; and immunosuppression, such as that caused by HIV co-infection.2,5

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 25-year-old Bangladeshi man presented to our community hospital for evaluation of a painful leg ulcer of 1 month’s duration. The patient had migrated from Bangladesh to Panama, then to Costa Rica, followed by Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and, last, Texas. In Texas, he was identified by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, transported to a detention facility, and transferred to this hospital shortly afterward.

The patient reported that, during his extensive migration, he had lived in the jungle and reported what he described as mosquito bites on the legs. He subsequently developed a 3-cm ulcerated and crusted plaque with rolled borders on the right medial ankle (Figure 1). In addition, he had a palpable nodular cord on the medial leg from the ankle lesion to the mid thigh that was consistent with lymphocutaneous spread. Ultrasonography was negative for deep-vein thrombosis.

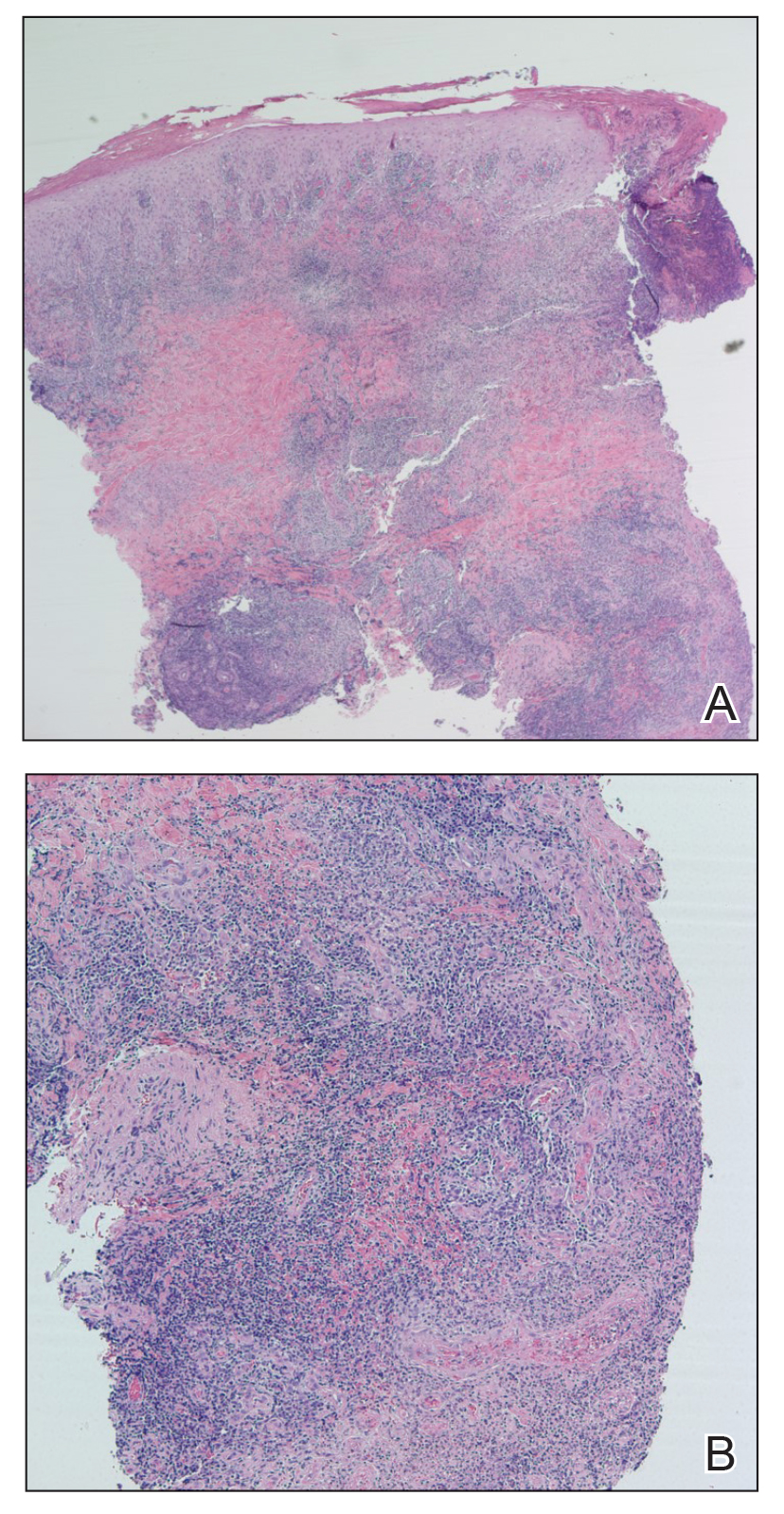

Because the patient’s recent migration from Central America was highly concerning for microbial infection, vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam were started empirically on admission. A punch biopsy from the right medial ankle was nondiagnostic, showing acute and chronic necrotizing inflammation along with numerous epithelioid histiocytes with a vaguely granulomatous appearance (Figure 2). A specimen from the right medial ankle that had already been taken by an astute border patrol medical provider was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for polymerase chain reaction analysis following admission and was found to be positive for Leishmania panamensis.