To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 16.5 million adults in the United States.1 Atopic dermatitis is associated with skin barrier dysfunction and the activation of type 2 inflammatory cytokines. Multiorgan involvement of AD has been demonstrated, as patients with AD are more prone to asthma, allergic rhinitis, and other systemic diseases.2 In 2020, Smirnova et al3 reported a significant association (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.58; 95% CI, 1.30-1.92) between AD and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in a large Swedish population. Currently, there is a lack of research evaluating the association between AD and COPD in a population of US adults. Therefore, we explored the association between AD and COPD (chronic bronchitis or emphysema) in a population of US adults utilizing the 1999-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), as these were the latest data for AD available in NHANES.4

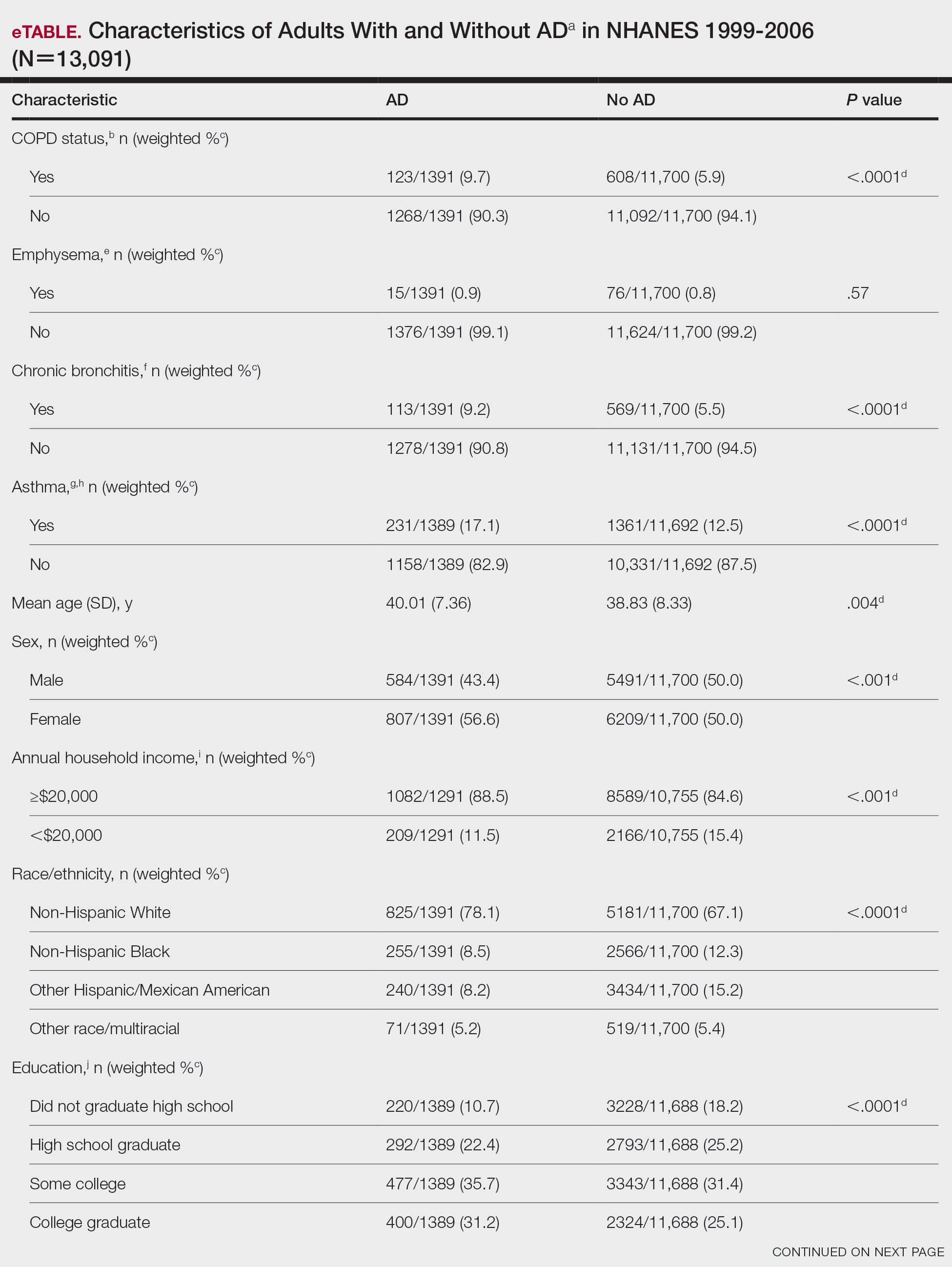

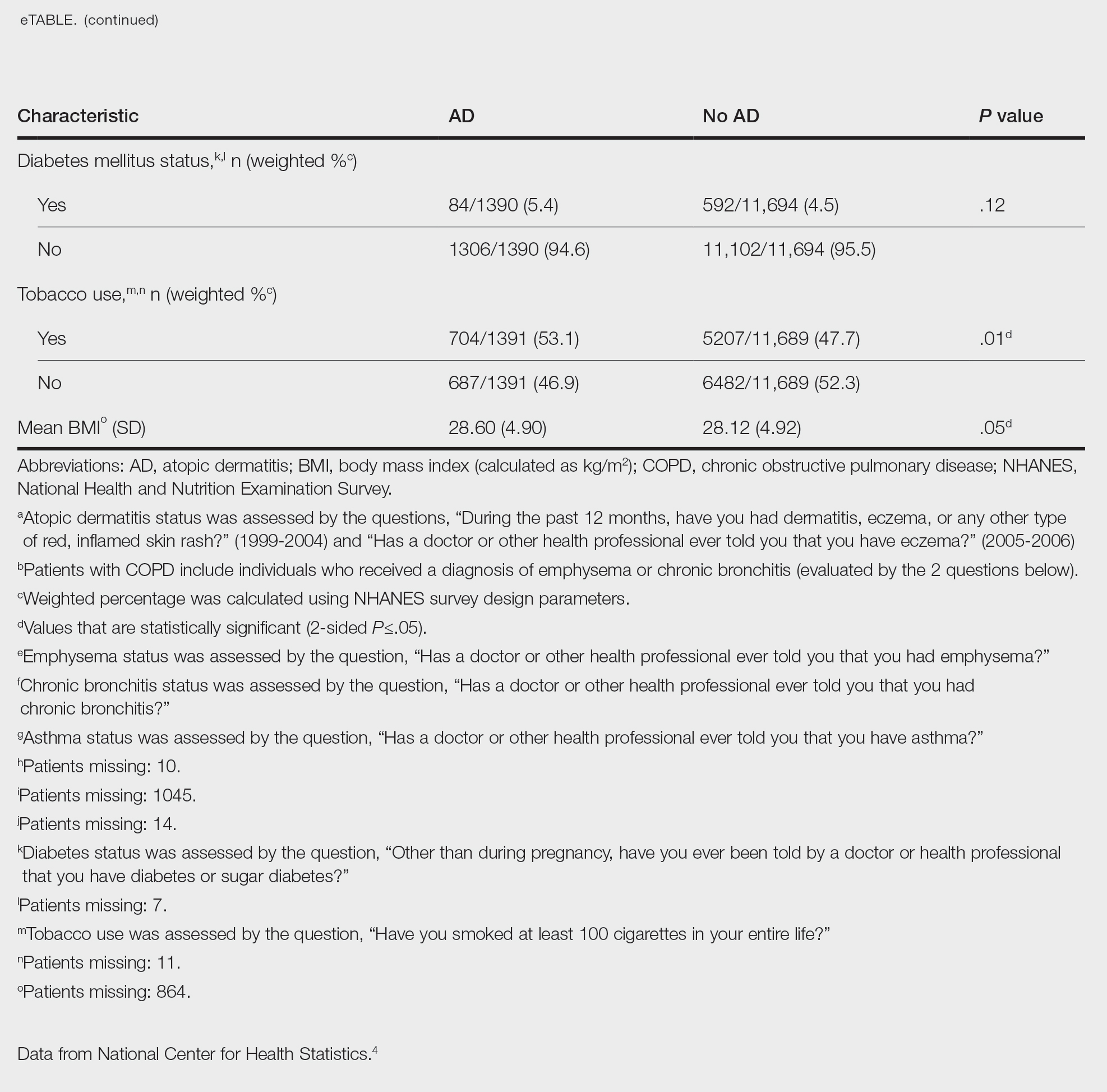

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 1999-2006 NHANES database. Three outcome variables—emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and COPD—and numerous confounding variables for each participant were extracted from the NHANES database. The original cohort consisted of 13,134 participants, and 43 patients were excluded from our analysis owing to the lack of response to survey questions regarding AD and COPD status. The relationship between AD and COPD was evaluated by multivariable logistic regression analyses utilizing Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our logistic regression models, we controlled for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, tobacco usage, diabetes mellitus and asthma status, and body mass index (eTable).

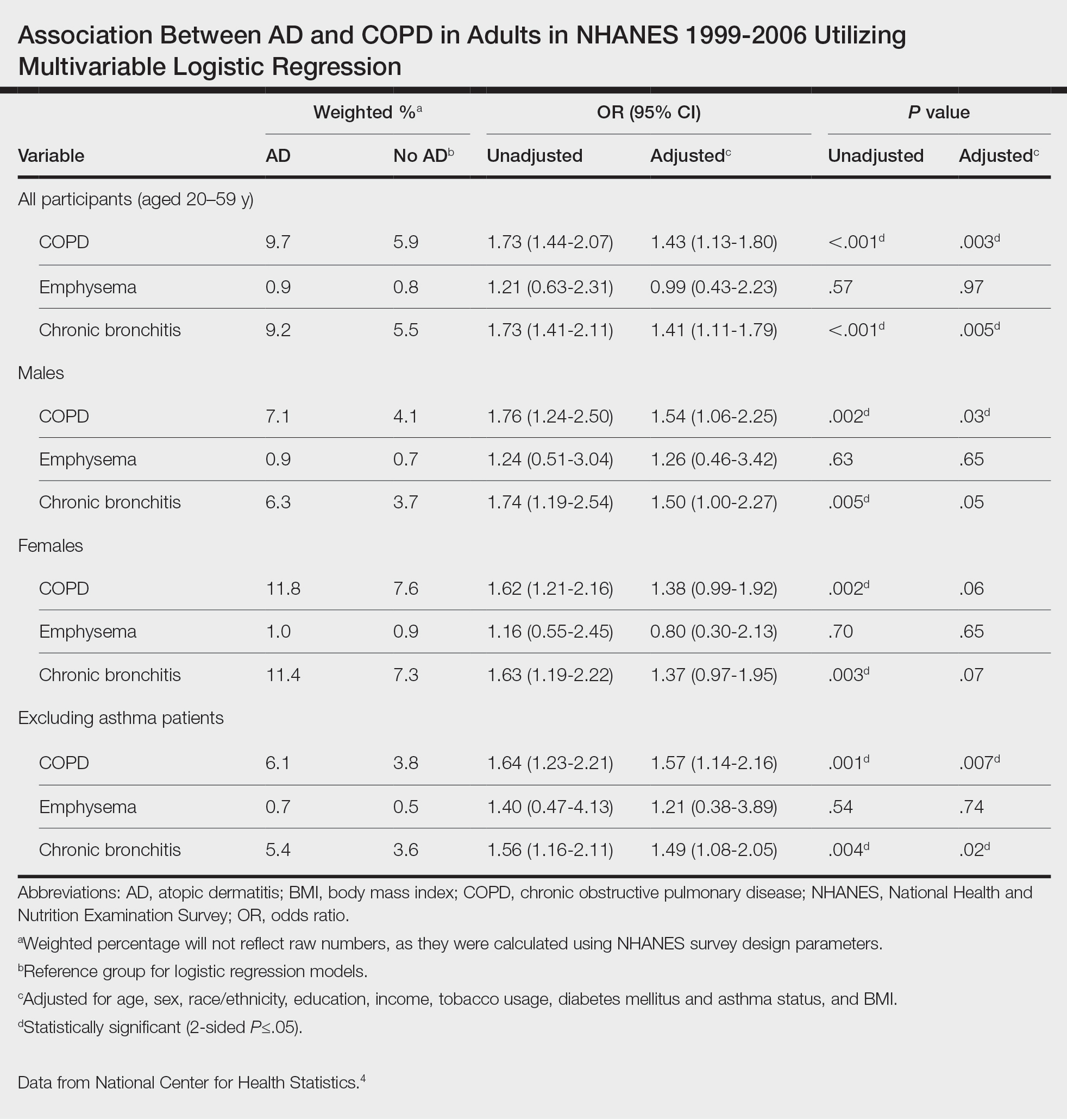

Our study consisted of 13,091 participants. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between AD and COPD (Table). Approximately 12.5% (weighted) of the patients in our analysis had AD. Additionally, 9.7% (weighted) of patients with AD had received a diagnosis of COPD; conversely, 5.9% (weighted) of patients without AD had received a diagnosis of COPD. More patients with AD reported a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis (9.2%) rather than emphysema (0.9%). Our analysis revealed a significant association between AD and COPD among adults aged 20 to 59 years (AOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.13-1.80; P=.003) after controlling for potential confounding variables. Subsequently, we performed subgroup analyses, including exclusion of patients with an asthma diagnosis, to further explore the association between AD and COPD. After excluding participants with asthma, there was still a significant association between AD and COPD (AOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.14-2.16; P=.007). Moreover, the odds of receiving a COPD diagnosis were significantly higher among male patients with AD (AOR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.06-2.25; P=.03).

Our results support the association between AD and COPD, more specifically chronic bronchitis. This finding may be due to similar pathogenic mechanisms in both conditions, including overlapping cytokine production and immune pathways.5 Additionally, Harazin et al6 discussed the role of a novel gene, collagen 29A1 (COL29A1), in the pathogenesis of AD, COPD, and asthma. Variations in this gene may predispose patients to not only atopic diseases but also COPD.6

Limitations of our study include self-reported diagnoses and lack of patients older than 59 years. Self-reported diagnoses could have resulted in some misclassification of COPD, as some individuals may have reported a diagnosis of COPD rather than their true diagnosis of asthma. We mitigated this limitation by constructing a subpopulation model with exclusion of individuals with asthma. Further studies with spirometry-diagnosed COPD are needed to explore this relationship and the potential contributory pathophysiologic mechanisms. Understanding this association may increase awareness of potential comorbidities and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.