Acrylates are a ubiquitous family of synthetic thermoplastic resins that are employed in a wide array of products. Since the discovery of acrylic acid in 1843 and its industrialization in the early 20th century, acrylates have been used by many different sectors of industry.1 Today, acrylates can be found in diverse sources such as adhesives, coatings, electronics, nail cosmetics, dental materials, and medical devices. Although these versatile compounds have revolutionized numerous sectors, their potential to trigger allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) has garnered considerable attention in recent years. In 2012, acrylates as a group were named Allergen of the Year by the American Contact Dermatitis Society,2 and one member—isobornyl acrylate—also was given the infamous award in 2020.3 In this article, we highlight the chemistry of acrylates, the growing prevalence of acrylate contact allergy, common sources of exposure, patch testing considerations, and management/prevention strategies.

Chemistry and Uses of Acrylates

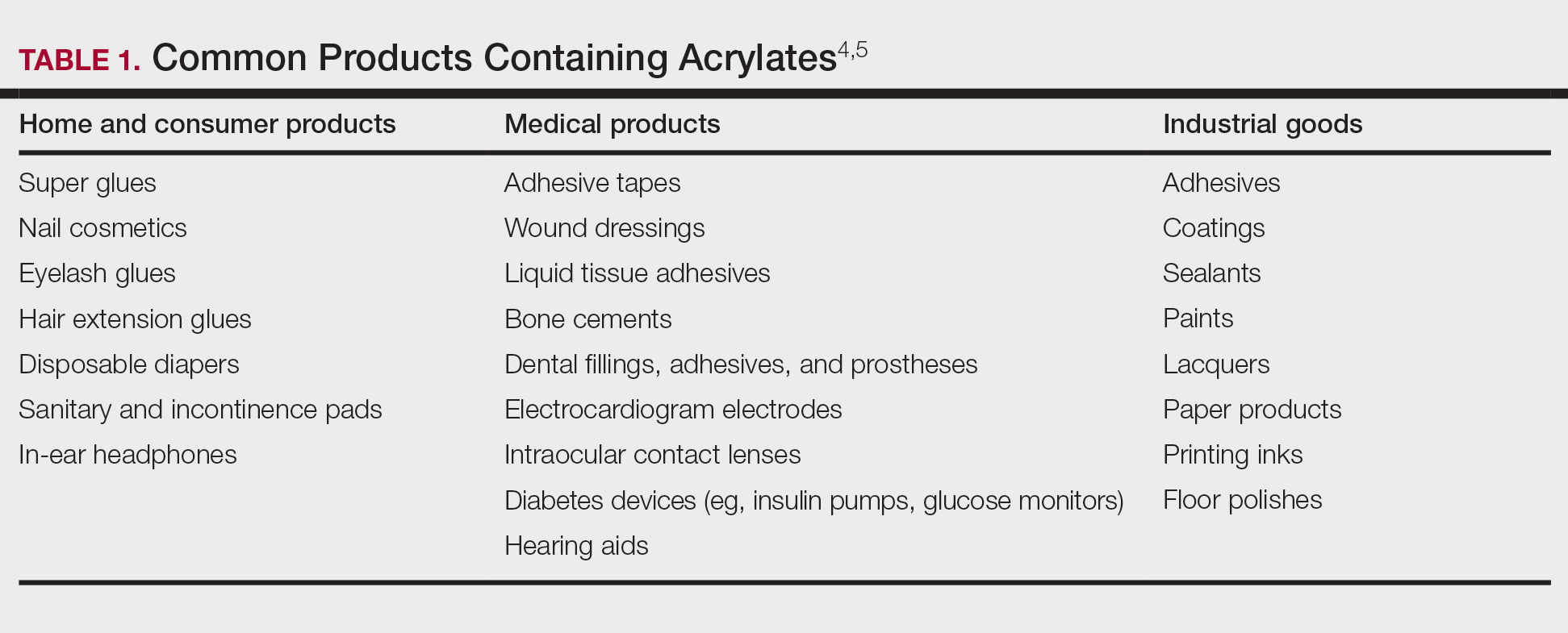

Acrylates are widely used due to their pliable and resilient properties.4 They begin as liquid monomers of (meth)acrylic acid or cyanoacrylic acid that are molded to the desired application before being cured or hardened by one of several means: spontaneously, using chemical catalysts, or with heat, UV light, or a light-emitting diode. Once cured, the final polymers (ie, [meth]acrylates, cyanoacrylates) serve a myriad of different purposes. Table 1 includes some of the more clinically relevant sources of acrylate exposure. Although this list is not comprehensive, it offers a glimpse into the vast array of uses for acrylates.

Acrylate Contact Allergy

Acrylic monomers are potent contact allergens, but the polymerized final products are not considered allergenic, assuming they are completely cured; however, ACD can occur with incomplete curing.6 It is of clinical importance that once an individual becomes sensitized to one type of acrylate, they may develop cross-reactions to others contained in different products. Notably, cyanoacrylates generally do not cross-react with (meth)acrylates; this has important implications for choosing safe alternative products in sensitized patients, though independent sensitization to cyanoacrylates is possible.7,8

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The prevalence of acrylate allergy in the general population is unknown; however, there is a trend of increased patch test positivity in studies of patients referred for patch testing. A 2018 study by the European Environmental Contact Dermatitis Research Group reported positive patch tests to acrylates in 1.1% of 18,228 patients tested from 2013 to 2015.9 More recently, a multicenter European study (2019-2020) reported a 2.3% patch test positivity to 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) among 7675 tested individuals,10 and even higher HEMA positivity was reported in Spain (3.7% of 1884 patients in 2019-2020).11 In addition, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) reported positive patch test reactions to HEMA in 3.2% of 4111 patients tested from 2019 to 2020, a statistically significant increase compared with those tested in 2009 to 2018 (odds ratio, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.03-1.51]; P=.02).12

Historically, acrylate sensitization primarily stemmed from occupational exposure. A retrospective analysis of occupational dermatitis performed by the NACDG (2001-2016) showed that HEMA was among the top 10 most common occupational allergens (3.4% positivity [83/2461]) and had the fifth highest percentage of occupationally relevant reactions (73.5% [83/113]).13 High-risk occupations include dental providers and nail technicians. Dentistry utilizes many materials containing acrylates, including uncured plastic resins used in dental prostheses, dentin bonding materials, and glass ionomers.14 A retrospective analysis of 585 dental personnel who were patch tested by the NACDG (2001-2018) found that more than 20% of occupational ACD cases were related to acrylates.15 Nail technicians are another group routinely exposed to acrylates through a variety of modern nail cosmetics. In a 7-year study from Portugal evaluating acrylate ACD, 68% (25/37) of cases were attributed to occupation, 80% (20/25) of which were in nail technicians.16 Likewise, among 28 nail technicians in Sweden who were referred for patch testing, 57% (16/28) tested positive for at least 1 acrylate.17

Modern Sources of Acrylate Exposure

Once thought to be a predominantly occupational exposure, acrylates have rapidly made their way into everyday consumer products. Clinicians should be aware of several sources of clinically relevant acrylate exposure, including nail cosmetics, consumer electronics, and medical/surgical adhesives.

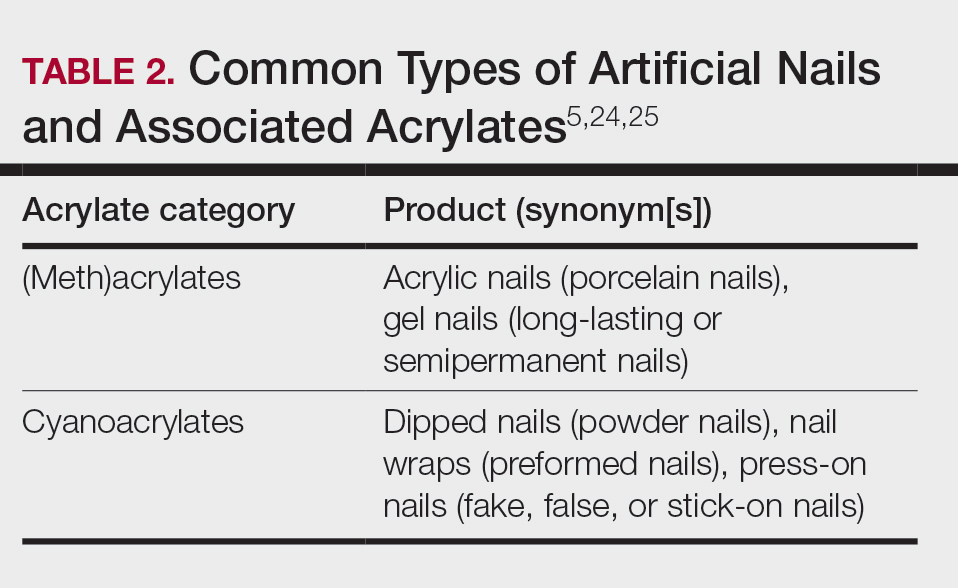

A 2016 study found a shift to nail cosmetics as the most common source of acrylate sensitization.18 Nail cosmetics that contain acrylates include traditional acrylic, gel (shellac), dipped, and press-on (false) nails.19 The NACDG found that the most common allergen in patients experiencing ACD associated with nail products (2001-2016) was HEMA (56.6% [273/482]), far ahead of the traditional nail polish allergen tosylamide (36.2% [273/755]). Over the study period, the frequency of positive patch tests statistically increased for HEMA (P=.0069) and decreased for tosylamide (P<.0001).20 There is concern that the use of home gel nail kits, which can be purchased online at the click of a button, may be associated with a risk for acrylate sensitization.21,22 A recent study surveyed a Facebook support group for individuals with self-reported reactions to nail cosmetics, finding that 78% of the 199 individuals had used at-home gel nail kits, and more than 80% of them first developed skin reactions after starting to use at-home kits.23 The risks for sensitization are thought to be greater when self-applying nail acrylates compared to having them done professionally because individuals are more likely to spill allergenic monomers onto the skin at home; it also is possible that home techniques could lead to incomplete curing. Table 2 reviews the different types of acrylic nail cosmetics.