Dementia is a family of disorders characterized by a decline in multiple cognitive abilities that significantly interferes with an individual’s functioning. An estimated 50 million people are living with a dementia worldwide.1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, accounting for approximately two-thirds of dementia cases.1 These numbers are expected to increase dramatically in the upcoming decades.

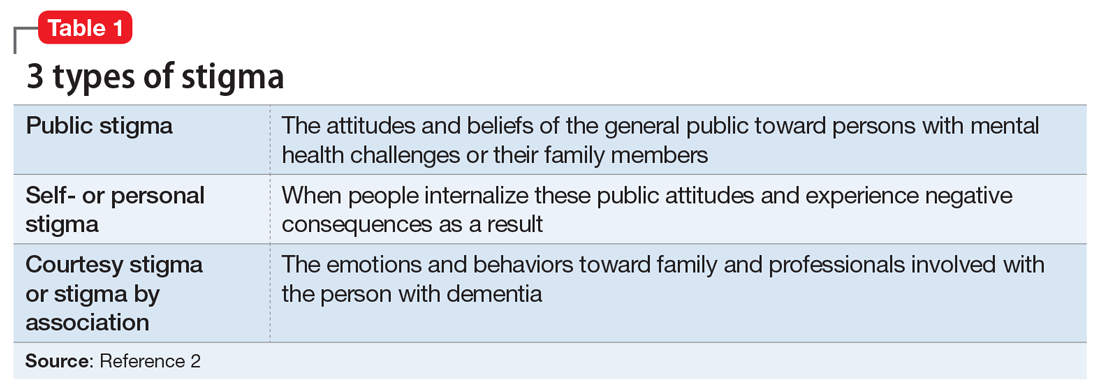

Sociologist Erving Goffman defined stigma as “an attribute, behaviour, or reputation which is socially discrediting in a particular way: it causes an individual to be mentally classified by others in an undesirable, rejected stereotype rather than in an accepted, normal one.”2 Goffman2 defined 3 broad categories of stigma: public, self, and courtesy (Table 12).

Considerable evidence shows that the combined impact of having dementia and the negative response to the diagnosis significantly undermines an individual’s psychosocial well-being and quality of life.3 Persons with dementia (PwD) commonly report a loss of identity and self-worth, and stigma appears to deepen this distress.3 Stigma also negatively affects individuals associated with PwD, including family members and professionals. In this article, we discuss the impact of dementia-related stigma, and steps you can take to address it, including implementing person-centered clinical practices, promoting anti-stigma messaging campaigns, and advocating for public policy action to improve the lives of PwD and their families.

A pervasive problem

Although the Alzheimer’s Society International and the World Health Organization acknowledge that stigma has a central role in defining the experience of AD, how stigma may present, how clinicians and researchers can recognize and measure stigma, and how to best combat it have been understudied.3-5 A recent systematic literature review examined worldwide evidence on dementia-related stigma over the past decade.6 Hermann et al6 found that health care providers and the general public may hold stigmatizing attitudes toward PwD, and that stigma may be particularly harsh among racial and ethnic minorities, although the literature is scarce in this area. Cultural factors may also worsen stigma, and stigma may be associated with reduced awareness of dementia services and reduced help-seeking among minority groups.7,8 Studies show that stigmatizing attitudes are more pronounced in people with limited knowledge of dementia, in those with little contact with PwD, in men, in younger individuals, and in the context of cultural interpretations of dementia.6 Health care providers can also sometimes contribute to the perpetuation of stigma.6

In terms of standardized scales or instruments for evaluating dementia-related stigma, there is no uniformly accepted “gold standard” measure, which makes it difficult to compare studies.6 In order to effectively study efforts to reduce stigma, researchers need to identify and establish a consensus on rating scales for evaluating stigma among PwD, caregivers, and the general public. Three instruments that may be used for this purpose are the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS),9 the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI),10 and the Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory in Primary Care (PRISM-PC).11

The detrimental effects of stigma

Burgener et al12 reported that personal stigma impacted functioning and quality of life in PwD. Higher levels of stigma were associated with higher anxiety, depression, and behavioral symptoms and lower self-esteem, social support, participation in activities, personal control, and physical health.12 Personal characteristics that may affect stigma include gender, location (rural vs urban), ethnicity, education level, and living arrangements (alone vs with family).12

In a subset of PwD with early-stage memory loss (n = 22), Burgener and Buckwalter13 found that 42% of participants were reluctant to reveal their diagnosis to others, with some fearing they would no longer be allowed to live alone and would be “sent to a facility.” In addition, 46% indicated they did not want “to be talked about like they were not there.” More than 50% of participants reported changes in their social network after receiving the diagnosis, including reducing activities and limiting types of contacts (ie, telephone only) or interacting only when “people come to me.” Participants were most comfortable with good friends “who understand” and persons within their faith communities. When asked about how they were treated by family members, >50% of participants described being treated differently, including loss of financial independence, more limited contact, and being “treated like a baby” by their children, who in general were uncomfortable talking about the diagnosis.

Continue to: In a recent study...