User login

More on AI-generated content

In his recent editorial (“A ‘guest editorial’ … generated by ChatGPT?”

Sara Hartley, MD

Berkeley, California

I just read the “guest editorial” generated by ChatGPT. Thank you for this article. Although this is truly an amazing advancement in artificial intelligence (AI), I feel this guest editorial was very basic. It did not read like scientific writing. It read more like it was written at an 11th- or 12th-grade level, though I am fully aware that the question was simple, and thus the answer was not very deep. I can’t deny that if I had been tested, chances are good I would have fallen among the 32% of my peers who would not have recognized it as AI. I appreciate that you (and your team) are working on a protocol regarding how to include content generated by or with the help of AI. God knows if (most likely, when) people with evil minds will use AI to spread false information that may dispute the accredited scientific data and research that guide the medical world and many other fields. I wonder if AI can serve as a search engine that is better or easier to use than PubMed (for example) and the other services we use for research and learning.

Alex Mustachi, PMHNP-BC

Suffern, New York

I wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed reading your recent editorial on AI and scientific writing. Sharing the 4 AI-generated “articles” with readers (“For artificial intelligence, the future is finally here,”

Martha Sajatovic, MD

Cleveland, Ohio

Continue to: The AI-generated samples...

The Al-generated samples were fascinating. As far as I superficially noted, the spelling, grammar, and punctuation were correct. That is better than one gets from most student compositions. However, the articles were completely lacking in depth or apparent insight. The article on anosognosia mentioned it can be present in up to 50% of cases of schizophrenia. In my experience, it is present in approximately 99.9% of cases. It clearly did not consider if anosognosia is also present in alcoholics, codependents, abusers, or people with bizarre political beliefs. But I guess the “intelligence” wasn’t asked that. The other samples also show shallow thinking and repetitive wording—pretty much like my high school junior compositions.

Maybe an appropriate use for AI is a task such as evaluating suicide notes. AI’s success causes one to feel nonplussed. Much more disconcerting was a recent news article that reported AI made up nonexistent references to a professor’s alleged sexual harassment, and then generated citations to its own made-up reference.1 That is indeed frightening new territory. How does one fight against a machine to clear their own name?

Linda Miller, NP

Harrisonburg, Virginia

References

1. Verma P, Oremus W. ChatGPT invented a sexual harassment scandal and named a real law prof as the accused. The Washington Post. April 5, 2023. Accessed May 8, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/04/05/chatgpt-lies/

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah, for your latest thought-provoking articles on AI. Time and again you provide the profession with cutting-edge, relevant food for thought. Caveat emptor, indeed.

Lawrence E. Cormier, MD

Denver, Colorado

Continue to: We read with interest...

We read with interest Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial that invited readers to share their take on the quality of an AI-generated writing sample. I (MZP) was a computational neuroscience major at Columbia University and was accepted to medical school in 2022 at age 19. I identify with the character traits common among many young tech entrepreneurs driving the AI revolution—social awkwardness; discomfort with subjective emotions; restricted areas of interest; algorithmic thinking; strict, naive idealism; and an obsession with data. To gain a deeper understanding of Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI (the company that created ChatGPT), we analyzed a 2.5-hour interview that MIT research scientist Lex Fridman conducted with Altman.1 As a result, we began to discern why AI-generated text feels so stiff and bland compared to the superior fluidity and expressiveness of human communication. As of now, the creation is a reflection of its creator.

Generally speaking, computer scientists are not warm and fuzzy types. Hence, ChatGPT strives to be neutral, accurate, and objective compared to more biased and fallible humans, and, consequently, its language lacks the emotive flair we have come to relish in normal human interactions. In the interview, Altman discusses several solutions that will soon raise the quality of ChatGPT’s currently deficient emotional quotient to approximate its superior IQ. Altruistically, Altman has opened ChatGPT to all, so we can freely interact and utilize its potential to increase our productivity exponentially. As a result, ChatGPT interfaces with millions of humans through RLHF (reinforcement learning from human feedback), which makes each iteration more in tune with our sensibilities.2 Another initiative Altman is undertaking is to depart his Silicon Valley bubble for a road trip to interact with “regular people” and gain a better sense of how to make ChatGPT more user-friendly.1

What’s so saddening about Dr. Nasrallah’s homework assignment is that he is asking us to evaluate with our mature adult standards an article that was written at the emotional stage of a child in early high school. But our hubris and complacency are entirely unfounded because ChatGPT is learning much faster than we ever could, and it will quickly surpass us all as it continues to evolve.

It is also quite disconcerting to hear how Altman is naively relying upon governmental regulation and corporate responsibility to manage the potential misuse of future artificial general intelligence for social, economic, and political control and upheaval. We know well the harmful effects of the internet and social media, particularly on our youth, yet our laws still lag far behind the fact that these technological innovations are simultaneously enhancing our knowledge while destroying our souls. As custodians of our world, dedicated to promoting and preserving mental well-being, we cannot wait much longer to intervene in properly parenting AI along its wisest developmental trajectory before it is too late.

Maxwell Zachary Price, BA

Nutley, New Jersey

Richard Louis Price, MD

New York, New York

References

1. Sam Altman: OpenAI CEO on GPT-4, ChatGPT, and the Future of AI. Lex Fridman Podcast #367. March 25, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_Guz73e6fw

2. Heikkilä M. How OpenAI is trying to make ChatGPT safer and less biased. MIT Technology Review. Published February 21, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/02/21/1068893/how-openai-is-trying-to-make-chatgpt-safer-and-less-biased/

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their letters, or with manufacturers of competing products.

In his recent editorial (“A ‘guest editorial’ … generated by ChatGPT?”

Sara Hartley, MD

Berkeley, California

I just read the “guest editorial” generated by ChatGPT. Thank you for this article. Although this is truly an amazing advancement in artificial intelligence (AI), I feel this guest editorial was very basic. It did not read like scientific writing. It read more like it was written at an 11th- or 12th-grade level, though I am fully aware that the question was simple, and thus the answer was not very deep. I can’t deny that if I had been tested, chances are good I would have fallen among the 32% of my peers who would not have recognized it as AI. I appreciate that you (and your team) are working on a protocol regarding how to include content generated by or with the help of AI. God knows if (most likely, when) people with evil minds will use AI to spread false information that may dispute the accredited scientific data and research that guide the medical world and many other fields. I wonder if AI can serve as a search engine that is better or easier to use than PubMed (for example) and the other services we use for research and learning.

Alex Mustachi, PMHNP-BC

Suffern, New York

I wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed reading your recent editorial on AI and scientific writing. Sharing the 4 AI-generated “articles” with readers (“For artificial intelligence, the future is finally here,”

Martha Sajatovic, MD

Cleveland, Ohio

Continue to: The AI-generated samples...

The Al-generated samples were fascinating. As far as I superficially noted, the spelling, grammar, and punctuation were correct. That is better than one gets from most student compositions. However, the articles were completely lacking in depth or apparent insight. The article on anosognosia mentioned it can be present in up to 50% of cases of schizophrenia. In my experience, it is present in approximately 99.9% of cases. It clearly did not consider if anosognosia is also present in alcoholics, codependents, abusers, or people with bizarre political beliefs. But I guess the “intelligence” wasn’t asked that. The other samples also show shallow thinking and repetitive wording—pretty much like my high school junior compositions.

Maybe an appropriate use for AI is a task such as evaluating suicide notes. AI’s success causes one to feel nonplussed. Much more disconcerting was a recent news article that reported AI made up nonexistent references to a professor’s alleged sexual harassment, and then generated citations to its own made-up reference.1 That is indeed frightening new territory. How does one fight against a machine to clear their own name?

Linda Miller, NP

Harrisonburg, Virginia

References

1. Verma P, Oremus W. ChatGPT invented a sexual harassment scandal and named a real law prof as the accused. The Washington Post. April 5, 2023. Accessed May 8, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/04/05/chatgpt-lies/

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah, for your latest thought-provoking articles on AI. Time and again you provide the profession with cutting-edge, relevant food for thought. Caveat emptor, indeed.

Lawrence E. Cormier, MD

Denver, Colorado

Continue to: We read with interest...

We read with interest Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial that invited readers to share their take on the quality of an AI-generated writing sample. I (MZP) was a computational neuroscience major at Columbia University and was accepted to medical school in 2022 at age 19. I identify with the character traits common among many young tech entrepreneurs driving the AI revolution—social awkwardness; discomfort with subjective emotions; restricted areas of interest; algorithmic thinking; strict, naive idealism; and an obsession with data. To gain a deeper understanding of Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI (the company that created ChatGPT), we analyzed a 2.5-hour interview that MIT research scientist Lex Fridman conducted with Altman.1 As a result, we began to discern why AI-generated text feels so stiff and bland compared to the superior fluidity and expressiveness of human communication. As of now, the creation is a reflection of its creator.

Generally speaking, computer scientists are not warm and fuzzy types. Hence, ChatGPT strives to be neutral, accurate, and objective compared to more biased and fallible humans, and, consequently, its language lacks the emotive flair we have come to relish in normal human interactions. In the interview, Altman discusses several solutions that will soon raise the quality of ChatGPT’s currently deficient emotional quotient to approximate its superior IQ. Altruistically, Altman has opened ChatGPT to all, so we can freely interact and utilize its potential to increase our productivity exponentially. As a result, ChatGPT interfaces with millions of humans through RLHF (reinforcement learning from human feedback), which makes each iteration more in tune with our sensibilities.2 Another initiative Altman is undertaking is to depart his Silicon Valley bubble for a road trip to interact with “regular people” and gain a better sense of how to make ChatGPT more user-friendly.1

What’s so saddening about Dr. Nasrallah’s homework assignment is that he is asking us to evaluate with our mature adult standards an article that was written at the emotional stage of a child in early high school. But our hubris and complacency are entirely unfounded because ChatGPT is learning much faster than we ever could, and it will quickly surpass us all as it continues to evolve.

It is also quite disconcerting to hear how Altman is naively relying upon governmental regulation and corporate responsibility to manage the potential misuse of future artificial general intelligence for social, economic, and political control and upheaval. We know well the harmful effects of the internet and social media, particularly on our youth, yet our laws still lag far behind the fact that these technological innovations are simultaneously enhancing our knowledge while destroying our souls. As custodians of our world, dedicated to promoting and preserving mental well-being, we cannot wait much longer to intervene in properly parenting AI along its wisest developmental trajectory before it is too late.

Maxwell Zachary Price, BA

Nutley, New Jersey

Richard Louis Price, MD

New York, New York

References

1. Sam Altman: OpenAI CEO on GPT-4, ChatGPT, and the Future of AI. Lex Fridman Podcast #367. March 25, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_Guz73e6fw

2. Heikkilä M. How OpenAI is trying to make ChatGPT safer and less biased. MIT Technology Review. Published February 21, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/02/21/1068893/how-openai-is-trying-to-make-chatgpt-safer-and-less-biased/

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their letters, or with manufacturers of competing products.

In his recent editorial (“A ‘guest editorial’ … generated by ChatGPT?”

Sara Hartley, MD

Berkeley, California

I just read the “guest editorial” generated by ChatGPT. Thank you for this article. Although this is truly an amazing advancement in artificial intelligence (AI), I feel this guest editorial was very basic. It did not read like scientific writing. It read more like it was written at an 11th- or 12th-grade level, though I am fully aware that the question was simple, and thus the answer was not very deep. I can’t deny that if I had been tested, chances are good I would have fallen among the 32% of my peers who would not have recognized it as AI. I appreciate that you (and your team) are working on a protocol regarding how to include content generated by or with the help of AI. God knows if (most likely, when) people with evil minds will use AI to spread false information that may dispute the accredited scientific data and research that guide the medical world and many other fields. I wonder if AI can serve as a search engine that is better or easier to use than PubMed (for example) and the other services we use for research and learning.

Alex Mustachi, PMHNP-BC

Suffern, New York

I wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed reading your recent editorial on AI and scientific writing. Sharing the 4 AI-generated “articles” with readers (“For artificial intelligence, the future is finally here,”

Martha Sajatovic, MD

Cleveland, Ohio

Continue to: The AI-generated samples...

The Al-generated samples were fascinating. As far as I superficially noted, the spelling, grammar, and punctuation were correct. That is better than one gets from most student compositions. However, the articles were completely lacking in depth or apparent insight. The article on anosognosia mentioned it can be present in up to 50% of cases of schizophrenia. In my experience, it is present in approximately 99.9% of cases. It clearly did not consider if anosognosia is also present in alcoholics, codependents, abusers, or people with bizarre political beliefs. But I guess the “intelligence” wasn’t asked that. The other samples also show shallow thinking and repetitive wording—pretty much like my high school junior compositions.

Maybe an appropriate use for AI is a task such as evaluating suicide notes. AI’s success causes one to feel nonplussed. Much more disconcerting was a recent news article that reported AI made up nonexistent references to a professor’s alleged sexual harassment, and then generated citations to its own made-up reference.1 That is indeed frightening new territory. How does one fight against a machine to clear their own name?

Linda Miller, NP

Harrisonburg, Virginia

References

1. Verma P, Oremus W. ChatGPT invented a sexual harassment scandal and named a real law prof as the accused. The Washington Post. April 5, 2023. Accessed May 8, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/04/05/chatgpt-lies/

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah, for your latest thought-provoking articles on AI. Time and again you provide the profession with cutting-edge, relevant food for thought. Caveat emptor, indeed.

Lawrence E. Cormier, MD

Denver, Colorado

Continue to: We read with interest...

We read with interest Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial that invited readers to share their take on the quality of an AI-generated writing sample. I (MZP) was a computational neuroscience major at Columbia University and was accepted to medical school in 2022 at age 19. I identify with the character traits common among many young tech entrepreneurs driving the AI revolution—social awkwardness; discomfort with subjective emotions; restricted areas of interest; algorithmic thinking; strict, naive idealism; and an obsession with data. To gain a deeper understanding of Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI (the company that created ChatGPT), we analyzed a 2.5-hour interview that MIT research scientist Lex Fridman conducted with Altman.1 As a result, we began to discern why AI-generated text feels so stiff and bland compared to the superior fluidity and expressiveness of human communication. As of now, the creation is a reflection of its creator.

Generally speaking, computer scientists are not warm and fuzzy types. Hence, ChatGPT strives to be neutral, accurate, and objective compared to more biased and fallible humans, and, consequently, its language lacks the emotive flair we have come to relish in normal human interactions. In the interview, Altman discusses several solutions that will soon raise the quality of ChatGPT’s currently deficient emotional quotient to approximate its superior IQ. Altruistically, Altman has opened ChatGPT to all, so we can freely interact and utilize its potential to increase our productivity exponentially. As a result, ChatGPT interfaces with millions of humans through RLHF (reinforcement learning from human feedback), which makes each iteration more in tune with our sensibilities.2 Another initiative Altman is undertaking is to depart his Silicon Valley bubble for a road trip to interact with “regular people” and gain a better sense of how to make ChatGPT more user-friendly.1

What’s so saddening about Dr. Nasrallah’s homework assignment is that he is asking us to evaluate with our mature adult standards an article that was written at the emotional stage of a child in early high school. But our hubris and complacency are entirely unfounded because ChatGPT is learning much faster than we ever could, and it will quickly surpass us all as it continues to evolve.

It is also quite disconcerting to hear how Altman is naively relying upon governmental regulation and corporate responsibility to manage the potential misuse of future artificial general intelligence for social, economic, and political control and upheaval. We know well the harmful effects of the internet and social media, particularly on our youth, yet our laws still lag far behind the fact that these technological innovations are simultaneously enhancing our knowledge while destroying our souls. As custodians of our world, dedicated to promoting and preserving mental well-being, we cannot wait much longer to intervene in properly parenting AI along its wisest developmental trajectory before it is too late.

Maxwell Zachary Price, BA

Nutley, New Jersey

Richard Louis Price, MD

New York, New York

References

1. Sam Altman: OpenAI CEO on GPT-4, ChatGPT, and the Future of AI. Lex Fridman Podcast #367. March 25, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_Guz73e6fw

2. Heikkilä M. How OpenAI is trying to make ChatGPT safer and less biased. MIT Technology Review. Published February 21, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/02/21/1068893/how-openai-is-trying-to-make-chatgpt-safer-and-less-biased/

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their letters, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Long-Acting Injectables for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is a multifaceted condition associated with an increased risk for hospitalization and suicide as well as high costs to society and family.

In this ReCAP, Dr Martha Sajatovic, of the University Hospitals of Cleveland, discusses evidence of the short- and long-term consequences of bipolar disorder, including progressive neurologic impact such as changes in brain structure.

She discusses two FDA-approved long-acting injectables for bipolar disorder and considerations for their use, including their potential for first-line maintenance treatment and benefits for medication adherence.

Finally, she considers challenges in the clinical use of the long-acting injectables, including insufficient caregiver involvement and lack of awareness of the drugs' availability.

--

Martha Sajatovic, MD, Director, Neurological and Behavioral Outcomes Center, University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio

Martha Sajatovic, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: Otsuka; International Society for Bipolar Disorders; National Institutes of Health

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Otsuka; Janssen; Lundbeck; Teva; Neurelis

Received royalties from: Springer Press; Johns Hopkins University Press

Bipolar disorder is a multifaceted condition associated with an increased risk for hospitalization and suicide as well as high costs to society and family.

In this ReCAP, Dr Martha Sajatovic, of the University Hospitals of Cleveland, discusses evidence of the short- and long-term consequences of bipolar disorder, including progressive neurologic impact such as changes in brain structure.

She discusses two FDA-approved long-acting injectables for bipolar disorder and considerations for their use, including their potential for first-line maintenance treatment and benefits for medication adherence.

Finally, she considers challenges in the clinical use of the long-acting injectables, including insufficient caregiver involvement and lack of awareness of the drugs' availability.

--

Martha Sajatovic, MD, Director, Neurological and Behavioral Outcomes Center, University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio

Martha Sajatovic, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: Otsuka; International Society for Bipolar Disorders; National Institutes of Health

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Otsuka; Janssen; Lundbeck; Teva; Neurelis

Received royalties from: Springer Press; Johns Hopkins University Press

Bipolar disorder is a multifaceted condition associated with an increased risk for hospitalization and suicide as well as high costs to society and family.

In this ReCAP, Dr Martha Sajatovic, of the University Hospitals of Cleveland, discusses evidence of the short- and long-term consequences of bipolar disorder, including progressive neurologic impact such as changes in brain structure.

She discusses two FDA-approved long-acting injectables for bipolar disorder and considerations for their use, including their potential for first-line maintenance treatment and benefits for medication adherence.

Finally, she considers challenges in the clinical use of the long-acting injectables, including insufficient caregiver involvement and lack of awareness of the drugs' availability.

--

Martha Sajatovic, MD, Director, Neurological and Behavioral Outcomes Center, University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio

Martha Sajatovic, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: Otsuka; International Society for Bipolar Disorders; National Institutes of Health

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Otsuka; Janssen; Lundbeck; Teva; Neurelis

Received royalties from: Springer Press; Johns Hopkins University Press

Stigma in dementia: It’s time to talk about it

Dementia is a family of disorders characterized by a decline in multiple cognitive abilities that significantly interferes with an individual’s functioning. An estimated 50 million people are living with a dementia worldwide.1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, accounting for approximately two-thirds of dementia cases.1 These numbers are expected to increase dramatically in the upcoming decades.

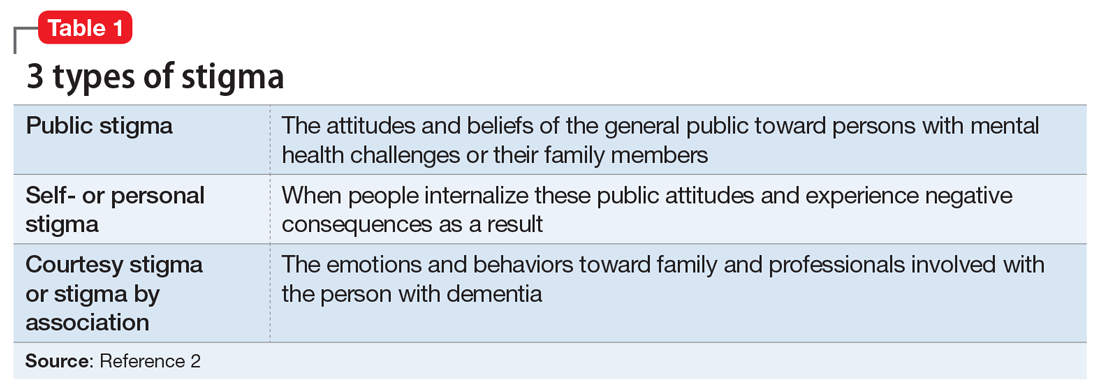

Sociologist Erving Goffman defined stigma as “an attribute, behaviour, or reputation which is socially discrediting in a particular way: it causes an individual to be mentally classified by others in an undesirable, rejected stereotype rather than in an accepted, normal one.”2 Goffman2 defined 3 broad categories of stigma: public, self, and courtesy (Table 12).

Considerable evidence shows that the combined impact of having dementia and the negative response to the diagnosis significantly undermines an individual’s psychosocial well-being and quality of life.3 Persons with dementia (PwD) commonly report a loss of identity and self-worth, and stigma appears to deepen this distress.3 Stigma also negatively affects individuals associated with PwD, including family members and professionals. In this article, we discuss the impact of dementia-related stigma, and steps you can take to address it, including implementing person-centered clinical practices, promoting anti-stigma messaging campaigns, and advocating for public policy action to improve the lives of PwD and their families.

A pervasive problem

Although the Alzheimer’s Society International and the World Health Organization acknowledge that stigma has a central role in defining the experience of AD, how stigma may present, how clinicians and researchers can recognize and measure stigma, and how to best combat it have been understudied.3-5 A recent systematic literature review examined worldwide evidence on dementia-related stigma over the past decade.6 Hermann et al6 found that health care providers and the general public may hold stigmatizing attitudes toward PwD, and that stigma may be particularly harsh among racial and ethnic minorities, although the literature is scarce in this area. Cultural factors may also worsen stigma, and stigma may be associated with reduced awareness of dementia services and reduced help-seeking among minority groups.7,8 Studies show that stigmatizing attitudes are more pronounced in people with limited knowledge of dementia, in those with little contact with PwD, in men, in younger individuals, and in the context of cultural interpretations of dementia.6 Health care providers can also sometimes contribute to the perpetuation of stigma.6

In terms of standardized scales or instruments for evaluating dementia-related stigma, there is no uniformly accepted “gold standard” measure, which makes it difficult to compare studies.6 In order to effectively study efforts to reduce stigma, researchers need to identify and establish a consensus on rating scales for evaluating stigma among PwD, caregivers, and the general public. Three instruments that may be used for this purpose are the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS),9 the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI),10 and the Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory in Primary Care (PRISM-PC).11

The detrimental effects of stigma

Burgener et al12 reported that personal stigma impacted functioning and quality of life in PwD. Higher levels of stigma were associated with higher anxiety, depression, and behavioral symptoms and lower self-esteem, social support, participation in activities, personal control, and physical health.12 Personal characteristics that may affect stigma include gender, location (rural vs urban), ethnicity, education level, and living arrangements (alone vs with family).12

In a subset of PwD with early-stage memory loss (n = 22), Burgener and Buckwalter13 found that 42% of participants were reluctant to reveal their diagnosis to others, with some fearing they would no longer be allowed to live alone and would be “sent to a facility.” In addition, 46% indicated they did not want “to be talked about like they were not there.” More than 50% of participants reported changes in their social network after receiving the diagnosis, including reducing activities and limiting types of contacts (ie, telephone only) or interacting only when “people come to me.” Participants were most comfortable with good friends “who understand” and persons within their faith communities. When asked about how they were treated by family members, >50% of participants described being treated differently, including loss of financial independence, more limited contact, and being “treated like a baby” by their children, who in general were uncomfortable talking about the diagnosis.

Continue to: In a recent study...

In a recent study by Harper et al,14 stigma was prevalent in the experience of PwD. One participant disclosed:

“I think there is [are] people I know who don’t ask me to go places or do things ’cause I have a dementia…I think lots of people don’t know what dementia is and I think it scares them ’cause they think of it as crazy. It hurts…”

Another participant said:

“I have had friends for over thirty years. They have turned their backs on me…we used to go for walks and they would phone me and go for coffee. Now I don’t hear from any of them…those aren’t true friends…true friends will stand behind you, not in front of you. That’s why I am not happy.”

Overall, quantitative and qualitative findings indicate multiple, detrimental effects of personal stigma on PwD. These effects fit well with measures of self-stigma, including social rejection (eg, being treated differently, participating in fewer activities, and having fewer friends), internalized shame (eg, being treated like a child, having fewer responsibilities, others acting as if dementia is “contagious”), and social isolation (eg, being less outgoing, feeling more comfortable in small groups, having limited social contacts).15

Continue to: Receiving a diagnosis of dementia...

Receiving a diagnosis of dementia presents patients and their families with psychological and social challenges.16 Many of these challenges are the consequence of stigma. A broad range of efforts are underway worldwide to reduce dementia-related stigma. These efforts include programs to promote public awareness and education, campaigns to develop inclusive social policies, and skills-based training initiatives to promote delivery of patient-centered care by clinicians and educators.3,17,18 Many of these efforts share a common focus on promoting the “dignity” and “personhood” of PwD in order to disrupt stereotypes or fixed, oversimplified beliefs associated with dementia.

Implementing person-centered clinical care

In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Health care communications that call attention to stereotypes may allow PwD to identify stereotypes as well as inaccuracies in those stereotypes. Interventions that validate the value of diversity can help PwD accept the ways in which they may not conform to social norms. This could include language such as “There is no one way to have Alzheimer’s disease. A person’s experience can differ from what others might experience or expect, and that’s okay.” In addition, the use of language that is accurate, respectful, inclusive, and empowering can support PwD and their caregivers.19,20 For example, referring to PwD as “individuals living with dementia” rather than “those who are demented” conveys respect and appreciation for personhood. Other clinicians have provided additional practical suggestions.21

Anti-stigma messaging campaigns

The mass media is a common source of stereotypes about AD and other dementias. They typically present a “worst-case” scenario that promotes ageism, gerontophobia, and negative emotions, which may worsen stigma and discrimination towards PwD and the people who care for them. However, public messaging campaigns are emerging to counter negative messages and stereotypes in the mass media. Projects such as Typical Day, People with Dementia, and other online anti-stigma messaging campaigns allow a broad audience to gain a more nuanced understanding of the lives of PwD and their caregivers. These projects are rich resources that offer education and personal stories that can counter common stereotypes about dementia.

Typical Day is a photography project developed and maintained by clinicians and researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. Since early 2017, the project has provided a forum for individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia to document their lives and show what it means to them to live with dementia. Participants in the project photo-document the people, places, and objects that define their daily lives. They review and explain these photos with researchers at Penn Memory Center, who help them tell their stories. The participants’ stories, the photos they capture, and their portraits are available at www.mytypicalday.org.

People of Dementia. Storytelling is a powerful way to raise awareness of and reduce the stigma associated with dementia. For PwD, telling their stories can be an effective and therapeutic way to communicate their emotions and deliver an important message. In the blog People of Dementia (www.peopleofdementia.com),22,23 PwD highlight who they were before the disease and how things have changed, with family members highlighting the challenges of caring for a person with dementia.

Continue to: The common thread is...

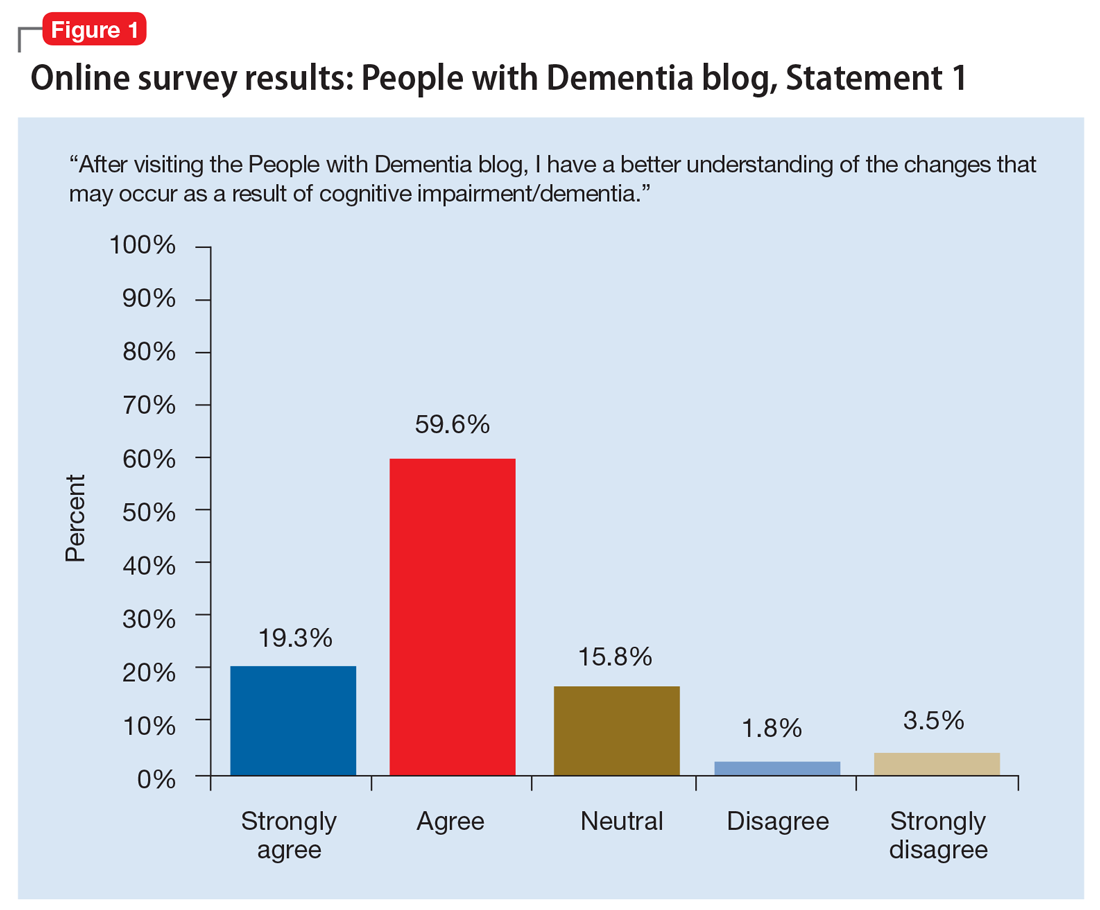

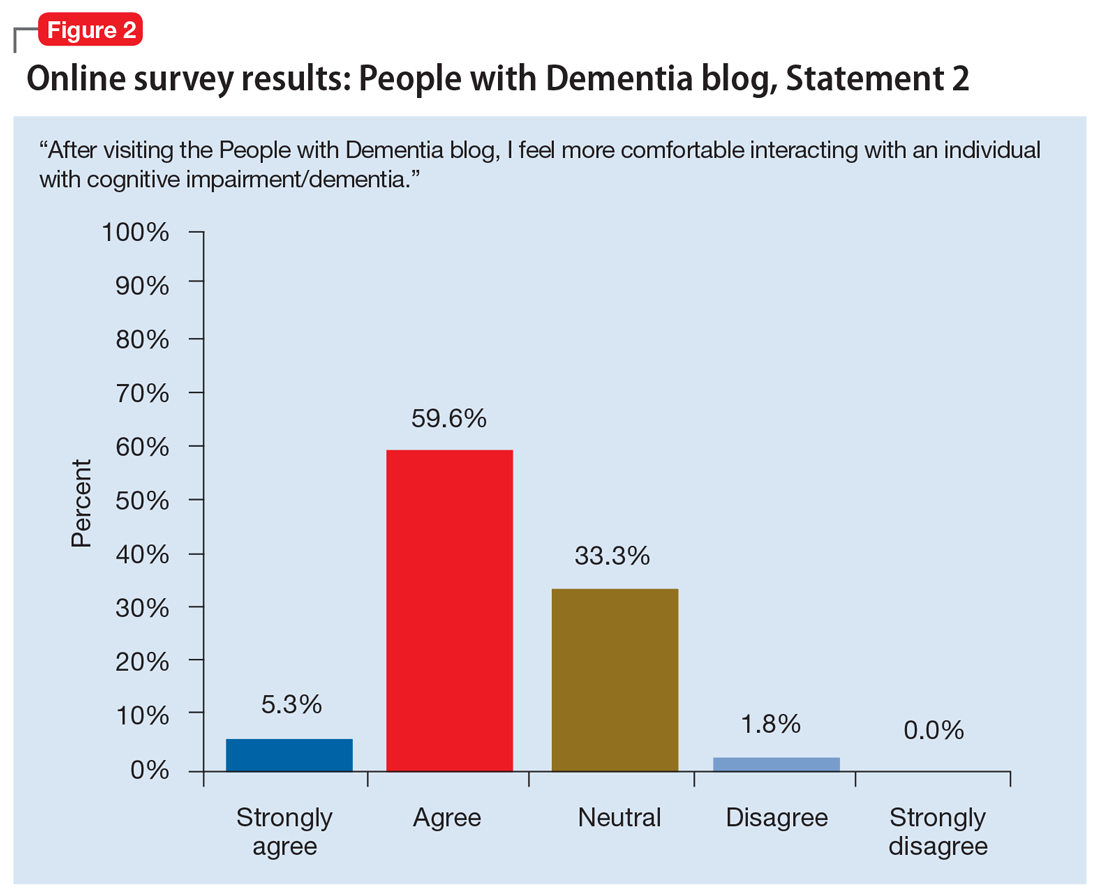

The common thread is the enduring “person” behind the exterior that is obscured by dementia. By allowing the audience to form a connection with who the individual was prior to the disease, and understanding the changes that have come as a result of dementia to both PwD and their support network, readers gain a greater appreciation of those affected by dementia. Between May 1, 2017 and May 31, 2019, the blog had more than 3,860 visitors. In an accompanying online survey (N = 57), 79% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that after visiting the People of Dementia blog, they had a better understanding of the changes that occur as a result of cognitive impairment/dementia (Figure 1). Almost two-thirds of respondents (65%) agreed/strongly agreed that they felt more comfortable interacting with PwD (Figure 2). Additionally, 60% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that they were more encouraged to work with PwD, and 90% agreed/strongly agreed that they had a greater appreciation of the challenges of being a caregiver for PwD. Overall, these findings suggest that the People of Dementia blog is useful for engaging the public and promoting a better understanding of dementia.

Work for policy changes

Clinicians can support public policy through education and advocacy both in the delivery of care and as spokespersons and stakeholders in their local communities. Public policies are important for providing access to medical and social services to meet the needs of PwD and their caregivers. The absence—real or perceived—of sufficient resources exacerbates dementia-related stigma. In addition to facilitating access to resources, national dementia strategies or legal frameworks, such as the National Alzheimer’s Project Act in the United States, include policy initiatives to identify and promote communication approaches that are effective and sensitive with respect to people living with dementia and their caregivers.

State and local legislators and patient advocates are leading policy efforts to reduce dementia-related stigma. For example, Colorado recently changed statutory references from being specific to diseases that cause dementia to the broader, more inclusive phrase “dementia diseases and related disabilities.”18 In addition to making funds available to support caregiving services for PwD, this legislative change added training for first responders to better meet the needs of missing PwD, and shifted the terminology used to diagnose and communicate about diseases causing dementia. The shift in language added new terminology that was chosen for being more person-centered to replace prior references to “senior senility,” “senility,” and other terms with pejorative meanings.

In Canada, a National Dementia Strategy will commit the Canadian government to action with definitive timelines, targets, reporting structures, and measurable outcomes.24

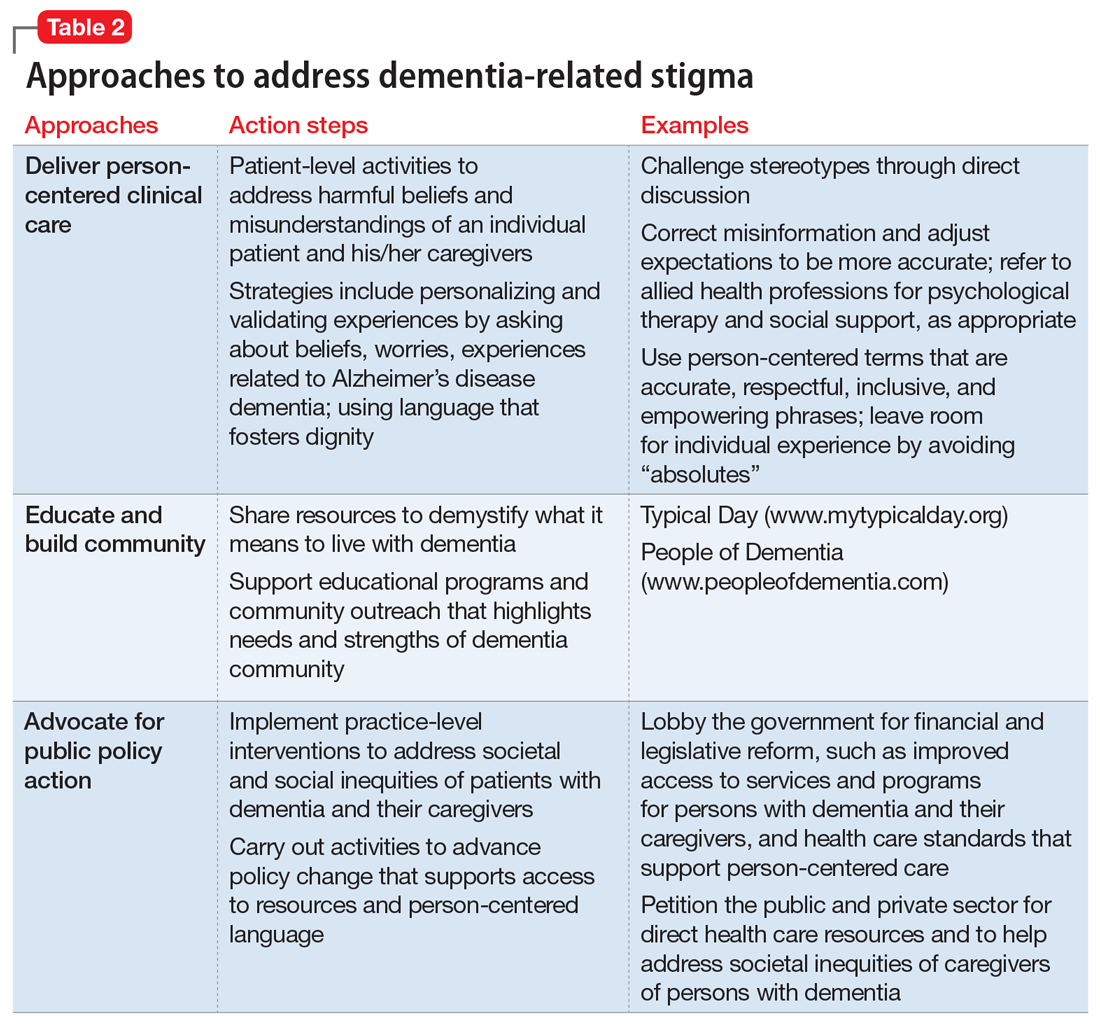

Table 2 summarizes approaches to a

Continue to: An open discussion

An open discussion

Larger studies and testing of diverse approaches are needed to better understand whether intergenerational initiatives or other approaches can genuinely modify stigmatizing attitudes in various dementia populations, especially considering language, health literacy, cultural preferences, and other needs. The identified effects on physical and mental health, quality of life, self-esteem, and behavioral symptoms further support the extensive, negative effects of self-stigma on PwD, and emphasize the need to develop and test interventions to ameliorate these effects.

We presented at a Stigma Symposium at the 2018 Gerontological Society of America Annual Scientific Meeting in Boston, Massachusetts.25 Attendees of this conference shared our concerns about the detrimental effects of stigma. The main question we were asked was “What can we do to reduce stigma?” Perhaps the most immediate response is that in order to move the stigma dial, clinicians need to recognize that stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on PwD and their families.6 Bringing the discussion into the open and targeting stigma at multiple levels needs to be addressed by clinicians, researchers, administrators, and society at large.

Bottom Line

Stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on persons with dementia and their families. In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Anti-stigma messaging campaigns and public policy changes also can be used to address societal and social inequities of patients with dementia and their caregivers.

Related Resources

- Khoury R, Shach R, Nair A, et al. Can lifestyle modifications delay or prevent Alzheimer’s disease? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):29-36,38.

- Burke AD, Burke WJ. Antipsychotics for patients with dementia: The road less traveled. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):26-32,35-37.

1. World Health Organization. Towards a dementia plan: a WHO guide. https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/policy_guidance/en/. Published 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

2. Goffman E. Stigma. New York, NY: Prentice-Hall; 1963:1-123.

3. Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2012: overcoming the stigma of dementia. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2012.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed May 28, 2019.

4. Blay SL, Peluso ETP. Public stigma: the community’s tolerance of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):163-171.

5. Piver LC, Nubukpo P, Faure A, et al. Describing perceived stigma against Alzheimer’s disease in a general population in France: the STIG-MA survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(9):933-938.

6. Herrmann LK, Welter E, Leverenz J, et al. A systematic review of dementia-related stigma research: can we move the stigma dial? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):316-331.

7. Eng KJ, Woo BKP. Knowledge of dementia community resources and stigma among Chinese American immigrants. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(1):e3-e4. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.11.003.

8. Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga D. Knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease, feelings of shame, and awareness of services among Korean American elders. J Aging Health. 2010;22(4):419-433.

9. Werner P, Goldstein D, Heinik J. Development and validity of the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s disease scale (FS-ADS). Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2011;25(1):42-48.

10. Rao D, Choi SW, Victorson D, et al. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: the development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI). Qual Life Res. 2009;18(5):585-595.

11. Boustani M, Perkins AJ, Monahan P, et al. Measuring primary care patients’ attitudes about dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(8):812-820.

12. Burgener SC, Buckwalter K, Perkounkova Y, et al. Perceived stigma in persons with early-stage dementia: longitudinal findings: Part 2. Dementia. 2015;14(5):609-632.

13. Burgener SC, Buckwalter K. The effects of perceived stigma on persons with dementia and their family caregivers. In: Symposium on Stigma: It’s time to talk about it. Boston, MA: Gerontological Society of America 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting; 2018. Session 2805.

14. Harper L, Dobbs B, Royan H, et al. The experience of stigma in care partners of people with dementia – results from an exploratory study. In Symposium on stigma: it’s time to talk about it. Boston, MA: Gerontological Society of America 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting; 2018. Session 2805.

15. Burgener S, Berger B. Measuring perceived stigma in persons with progressive neurological disease: Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson disease. Dementia. 2008;7(1):31-53.

16. Stites SD, Milne R, Karlawish J. Advances in Alzheimer’s imaging are changing the experience of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018;10;285-300.

17. Anderson LA, Egge R. Expanding efforts to address Alzheimer’s disease: the Healthy Brain Initiative. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014;10(50):S453-S456.

18. Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup. Report on the milestones for the US National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2014;10(Suppl 5);S430-S452. doi:10.1016/j/jalz.2014.08.103.

19. Kirkman AM. Dementia in the news: the media coverage of Alzheimer’s disease. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2006;25(2):74-79.

20. Swaffer, K. Dementia: stigma, language, and dementia-friendly. Dementia. 2014;13(6):709-716.

21. Stites SD, Karlawish J. Stigma of Alzheimer’s disease dementia: considerations for practice. Practical Neurology. https://practicalneurology.com/articles/2018-june/stigma-of-alzheimers-disease-dementia. Published June 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

22. Jamieson J, Dobbs B, Charles L, et al. Forgetful, but not forgotten people of dementia: a novel, technology focused project with a humanistic touch. Geriatric Grand Rounds; October 10, 2017. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

23. Dobbs B, Charles L, Chan K, et al. People of Dementia. CGS 37th Annual Scientific Meeting: Integrating Care, Making an Impact. Can Geriatr J. 2017;20(3):220.

24. Government of Canada. Conference report: National Dementia Conference. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/publications/diseases-conditions/national-dementia-conference-report.html. Government of Canada. Published August 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

25. The Gerontological Society of America. Program Abstracts from the GSA 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting “The Purposes of Longer Lives.” Innovation in Aging. 2018;2(Suppl 1):143.

Dementia is a family of disorders characterized by a decline in multiple cognitive abilities that significantly interferes with an individual’s functioning. An estimated 50 million people are living with a dementia worldwide.1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, accounting for approximately two-thirds of dementia cases.1 These numbers are expected to increase dramatically in the upcoming decades.

Sociologist Erving Goffman defined stigma as “an attribute, behaviour, or reputation which is socially discrediting in a particular way: it causes an individual to be mentally classified by others in an undesirable, rejected stereotype rather than in an accepted, normal one.”2 Goffman2 defined 3 broad categories of stigma: public, self, and courtesy (Table 12).

Considerable evidence shows that the combined impact of having dementia and the negative response to the diagnosis significantly undermines an individual’s psychosocial well-being and quality of life.3 Persons with dementia (PwD) commonly report a loss of identity and self-worth, and stigma appears to deepen this distress.3 Stigma also negatively affects individuals associated with PwD, including family members and professionals. In this article, we discuss the impact of dementia-related stigma, and steps you can take to address it, including implementing person-centered clinical practices, promoting anti-stigma messaging campaigns, and advocating for public policy action to improve the lives of PwD and their families.

A pervasive problem

Although the Alzheimer’s Society International and the World Health Organization acknowledge that stigma has a central role in defining the experience of AD, how stigma may present, how clinicians and researchers can recognize and measure stigma, and how to best combat it have been understudied.3-5 A recent systematic literature review examined worldwide evidence on dementia-related stigma over the past decade.6 Hermann et al6 found that health care providers and the general public may hold stigmatizing attitudes toward PwD, and that stigma may be particularly harsh among racial and ethnic minorities, although the literature is scarce in this area. Cultural factors may also worsen stigma, and stigma may be associated with reduced awareness of dementia services and reduced help-seeking among minority groups.7,8 Studies show that stigmatizing attitudes are more pronounced in people with limited knowledge of dementia, in those with little contact with PwD, in men, in younger individuals, and in the context of cultural interpretations of dementia.6 Health care providers can also sometimes contribute to the perpetuation of stigma.6

In terms of standardized scales or instruments for evaluating dementia-related stigma, there is no uniformly accepted “gold standard” measure, which makes it difficult to compare studies.6 In order to effectively study efforts to reduce stigma, researchers need to identify and establish a consensus on rating scales for evaluating stigma among PwD, caregivers, and the general public. Three instruments that may be used for this purpose are the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS),9 the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI),10 and the Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory in Primary Care (PRISM-PC).11

The detrimental effects of stigma

Burgener et al12 reported that personal stigma impacted functioning and quality of life in PwD. Higher levels of stigma were associated with higher anxiety, depression, and behavioral symptoms and lower self-esteem, social support, participation in activities, personal control, and physical health.12 Personal characteristics that may affect stigma include gender, location (rural vs urban), ethnicity, education level, and living arrangements (alone vs with family).12

In a subset of PwD with early-stage memory loss (n = 22), Burgener and Buckwalter13 found that 42% of participants were reluctant to reveal their diagnosis to others, with some fearing they would no longer be allowed to live alone and would be “sent to a facility.” In addition, 46% indicated they did not want “to be talked about like they were not there.” More than 50% of participants reported changes in their social network after receiving the diagnosis, including reducing activities and limiting types of contacts (ie, telephone only) or interacting only when “people come to me.” Participants were most comfortable with good friends “who understand” and persons within their faith communities. When asked about how they were treated by family members, >50% of participants described being treated differently, including loss of financial independence, more limited contact, and being “treated like a baby” by their children, who in general were uncomfortable talking about the diagnosis.

Continue to: In a recent study...

In a recent study by Harper et al,14 stigma was prevalent in the experience of PwD. One participant disclosed:

“I think there is [are] people I know who don’t ask me to go places or do things ’cause I have a dementia…I think lots of people don’t know what dementia is and I think it scares them ’cause they think of it as crazy. It hurts…”

Another participant said:

“I have had friends for over thirty years. They have turned their backs on me…we used to go for walks and they would phone me and go for coffee. Now I don’t hear from any of them…those aren’t true friends…true friends will stand behind you, not in front of you. That’s why I am not happy.”

Overall, quantitative and qualitative findings indicate multiple, detrimental effects of personal stigma on PwD. These effects fit well with measures of self-stigma, including social rejection (eg, being treated differently, participating in fewer activities, and having fewer friends), internalized shame (eg, being treated like a child, having fewer responsibilities, others acting as if dementia is “contagious”), and social isolation (eg, being less outgoing, feeling more comfortable in small groups, having limited social contacts).15

Continue to: Receiving a diagnosis of dementia...

Receiving a diagnosis of dementia presents patients and their families with psychological and social challenges.16 Many of these challenges are the consequence of stigma. A broad range of efforts are underway worldwide to reduce dementia-related stigma. These efforts include programs to promote public awareness and education, campaigns to develop inclusive social policies, and skills-based training initiatives to promote delivery of patient-centered care by clinicians and educators.3,17,18 Many of these efforts share a common focus on promoting the “dignity” and “personhood” of PwD in order to disrupt stereotypes or fixed, oversimplified beliefs associated with dementia.

Implementing person-centered clinical care

In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Health care communications that call attention to stereotypes may allow PwD to identify stereotypes as well as inaccuracies in those stereotypes. Interventions that validate the value of diversity can help PwD accept the ways in which they may not conform to social norms. This could include language such as “There is no one way to have Alzheimer’s disease. A person’s experience can differ from what others might experience or expect, and that’s okay.” In addition, the use of language that is accurate, respectful, inclusive, and empowering can support PwD and their caregivers.19,20 For example, referring to PwD as “individuals living with dementia” rather than “those who are demented” conveys respect and appreciation for personhood. Other clinicians have provided additional practical suggestions.21

Anti-stigma messaging campaigns

The mass media is a common source of stereotypes about AD and other dementias. They typically present a “worst-case” scenario that promotes ageism, gerontophobia, and negative emotions, which may worsen stigma and discrimination towards PwD and the people who care for them. However, public messaging campaigns are emerging to counter negative messages and stereotypes in the mass media. Projects such as Typical Day, People with Dementia, and other online anti-stigma messaging campaigns allow a broad audience to gain a more nuanced understanding of the lives of PwD and their caregivers. These projects are rich resources that offer education and personal stories that can counter common stereotypes about dementia.

Typical Day is a photography project developed and maintained by clinicians and researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. Since early 2017, the project has provided a forum for individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia to document their lives and show what it means to them to live with dementia. Participants in the project photo-document the people, places, and objects that define their daily lives. They review and explain these photos with researchers at Penn Memory Center, who help them tell their stories. The participants’ stories, the photos they capture, and their portraits are available at www.mytypicalday.org.

People of Dementia. Storytelling is a powerful way to raise awareness of and reduce the stigma associated with dementia. For PwD, telling their stories can be an effective and therapeutic way to communicate their emotions and deliver an important message. In the blog People of Dementia (www.peopleofdementia.com),22,23 PwD highlight who they were before the disease and how things have changed, with family members highlighting the challenges of caring for a person with dementia.

Continue to: The common thread is...

The common thread is the enduring “person” behind the exterior that is obscured by dementia. By allowing the audience to form a connection with who the individual was prior to the disease, and understanding the changes that have come as a result of dementia to both PwD and their support network, readers gain a greater appreciation of those affected by dementia. Between May 1, 2017 and May 31, 2019, the blog had more than 3,860 visitors. In an accompanying online survey (N = 57), 79% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that after visiting the People of Dementia blog, they had a better understanding of the changes that occur as a result of cognitive impairment/dementia (Figure 1). Almost two-thirds of respondents (65%) agreed/strongly agreed that they felt more comfortable interacting with PwD (Figure 2). Additionally, 60% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that they were more encouraged to work with PwD, and 90% agreed/strongly agreed that they had a greater appreciation of the challenges of being a caregiver for PwD. Overall, these findings suggest that the People of Dementia blog is useful for engaging the public and promoting a better understanding of dementia.

Work for policy changes

Clinicians can support public policy through education and advocacy both in the delivery of care and as spokespersons and stakeholders in their local communities. Public policies are important for providing access to medical and social services to meet the needs of PwD and their caregivers. The absence—real or perceived—of sufficient resources exacerbates dementia-related stigma. In addition to facilitating access to resources, national dementia strategies or legal frameworks, such as the National Alzheimer’s Project Act in the United States, include policy initiatives to identify and promote communication approaches that are effective and sensitive with respect to people living with dementia and their caregivers.

State and local legislators and patient advocates are leading policy efforts to reduce dementia-related stigma. For example, Colorado recently changed statutory references from being specific to diseases that cause dementia to the broader, more inclusive phrase “dementia diseases and related disabilities.”18 In addition to making funds available to support caregiving services for PwD, this legislative change added training for first responders to better meet the needs of missing PwD, and shifted the terminology used to diagnose and communicate about diseases causing dementia. The shift in language added new terminology that was chosen for being more person-centered to replace prior references to “senior senility,” “senility,” and other terms with pejorative meanings.

In Canada, a National Dementia Strategy will commit the Canadian government to action with definitive timelines, targets, reporting structures, and measurable outcomes.24

Table 2 summarizes approaches to a

Continue to: An open discussion

An open discussion

Larger studies and testing of diverse approaches are needed to better understand whether intergenerational initiatives or other approaches can genuinely modify stigmatizing attitudes in various dementia populations, especially considering language, health literacy, cultural preferences, and other needs. The identified effects on physical and mental health, quality of life, self-esteem, and behavioral symptoms further support the extensive, negative effects of self-stigma on PwD, and emphasize the need to develop and test interventions to ameliorate these effects.

We presented at a Stigma Symposium at the 2018 Gerontological Society of America Annual Scientific Meeting in Boston, Massachusetts.25 Attendees of this conference shared our concerns about the detrimental effects of stigma. The main question we were asked was “What can we do to reduce stigma?” Perhaps the most immediate response is that in order to move the stigma dial, clinicians need to recognize that stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on PwD and their families.6 Bringing the discussion into the open and targeting stigma at multiple levels needs to be addressed by clinicians, researchers, administrators, and society at large.

Bottom Line

Stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on persons with dementia and their families. In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Anti-stigma messaging campaigns and public policy changes also can be used to address societal and social inequities of patients with dementia and their caregivers.

Related Resources

- Khoury R, Shach R, Nair A, et al. Can lifestyle modifications delay or prevent Alzheimer’s disease? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):29-36,38.

- Burke AD, Burke WJ. Antipsychotics for patients with dementia: The road less traveled. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):26-32,35-37.

Dementia is a family of disorders characterized by a decline in multiple cognitive abilities that significantly interferes with an individual’s functioning. An estimated 50 million people are living with a dementia worldwide.1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, accounting for approximately two-thirds of dementia cases.1 These numbers are expected to increase dramatically in the upcoming decades.

Sociologist Erving Goffman defined stigma as “an attribute, behaviour, or reputation which is socially discrediting in a particular way: it causes an individual to be mentally classified by others in an undesirable, rejected stereotype rather than in an accepted, normal one.”2 Goffman2 defined 3 broad categories of stigma: public, self, and courtesy (Table 12).

Considerable evidence shows that the combined impact of having dementia and the negative response to the diagnosis significantly undermines an individual’s psychosocial well-being and quality of life.3 Persons with dementia (PwD) commonly report a loss of identity and self-worth, and stigma appears to deepen this distress.3 Stigma also negatively affects individuals associated with PwD, including family members and professionals. In this article, we discuss the impact of dementia-related stigma, and steps you can take to address it, including implementing person-centered clinical practices, promoting anti-stigma messaging campaigns, and advocating for public policy action to improve the lives of PwD and their families.

A pervasive problem

Although the Alzheimer’s Society International and the World Health Organization acknowledge that stigma has a central role in defining the experience of AD, how stigma may present, how clinicians and researchers can recognize and measure stigma, and how to best combat it have been understudied.3-5 A recent systematic literature review examined worldwide evidence on dementia-related stigma over the past decade.6 Hermann et al6 found that health care providers and the general public may hold stigmatizing attitudes toward PwD, and that stigma may be particularly harsh among racial and ethnic minorities, although the literature is scarce in this area. Cultural factors may also worsen stigma, and stigma may be associated with reduced awareness of dementia services and reduced help-seeking among minority groups.7,8 Studies show that stigmatizing attitudes are more pronounced in people with limited knowledge of dementia, in those with little contact with PwD, in men, in younger individuals, and in the context of cultural interpretations of dementia.6 Health care providers can also sometimes contribute to the perpetuation of stigma.6

In terms of standardized scales or instruments for evaluating dementia-related stigma, there is no uniformly accepted “gold standard” measure, which makes it difficult to compare studies.6 In order to effectively study efforts to reduce stigma, researchers need to identify and establish a consensus on rating scales for evaluating stigma among PwD, caregivers, and the general public. Three instruments that may be used for this purpose are the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS),9 the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI),10 and the Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory in Primary Care (PRISM-PC).11

The detrimental effects of stigma

Burgener et al12 reported that personal stigma impacted functioning and quality of life in PwD. Higher levels of stigma were associated with higher anxiety, depression, and behavioral symptoms and lower self-esteem, social support, participation in activities, personal control, and physical health.12 Personal characteristics that may affect stigma include gender, location (rural vs urban), ethnicity, education level, and living arrangements (alone vs with family).12

In a subset of PwD with early-stage memory loss (n = 22), Burgener and Buckwalter13 found that 42% of participants were reluctant to reveal their diagnosis to others, with some fearing they would no longer be allowed to live alone and would be “sent to a facility.” In addition, 46% indicated they did not want “to be talked about like they were not there.” More than 50% of participants reported changes in their social network after receiving the diagnosis, including reducing activities and limiting types of contacts (ie, telephone only) or interacting only when “people come to me.” Participants were most comfortable with good friends “who understand” and persons within their faith communities. When asked about how they were treated by family members, >50% of participants described being treated differently, including loss of financial independence, more limited contact, and being “treated like a baby” by their children, who in general were uncomfortable talking about the diagnosis.

Continue to: In a recent study...

In a recent study by Harper et al,14 stigma was prevalent in the experience of PwD. One participant disclosed:

“I think there is [are] people I know who don’t ask me to go places or do things ’cause I have a dementia…I think lots of people don’t know what dementia is and I think it scares them ’cause they think of it as crazy. It hurts…”

Another participant said:

“I have had friends for over thirty years. They have turned their backs on me…we used to go for walks and they would phone me and go for coffee. Now I don’t hear from any of them…those aren’t true friends…true friends will stand behind you, not in front of you. That’s why I am not happy.”

Overall, quantitative and qualitative findings indicate multiple, detrimental effects of personal stigma on PwD. These effects fit well with measures of self-stigma, including social rejection (eg, being treated differently, participating in fewer activities, and having fewer friends), internalized shame (eg, being treated like a child, having fewer responsibilities, others acting as if dementia is “contagious”), and social isolation (eg, being less outgoing, feeling more comfortable in small groups, having limited social contacts).15

Continue to: Receiving a diagnosis of dementia...

Receiving a diagnosis of dementia presents patients and their families with psychological and social challenges.16 Many of these challenges are the consequence of stigma. A broad range of efforts are underway worldwide to reduce dementia-related stigma. These efforts include programs to promote public awareness and education, campaigns to develop inclusive social policies, and skills-based training initiatives to promote delivery of patient-centered care by clinicians and educators.3,17,18 Many of these efforts share a common focus on promoting the “dignity” and “personhood” of PwD in order to disrupt stereotypes or fixed, oversimplified beliefs associated with dementia.

Implementing person-centered clinical care

In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Health care communications that call attention to stereotypes may allow PwD to identify stereotypes as well as inaccuracies in those stereotypes. Interventions that validate the value of diversity can help PwD accept the ways in which they may not conform to social norms. This could include language such as “There is no one way to have Alzheimer’s disease. A person’s experience can differ from what others might experience or expect, and that’s okay.” In addition, the use of language that is accurate, respectful, inclusive, and empowering can support PwD and their caregivers.19,20 For example, referring to PwD as “individuals living with dementia” rather than “those who are demented” conveys respect and appreciation for personhood. Other clinicians have provided additional practical suggestions.21

Anti-stigma messaging campaigns

The mass media is a common source of stereotypes about AD and other dementias. They typically present a “worst-case” scenario that promotes ageism, gerontophobia, and negative emotions, which may worsen stigma and discrimination towards PwD and the people who care for them. However, public messaging campaigns are emerging to counter negative messages and stereotypes in the mass media. Projects such as Typical Day, People with Dementia, and other online anti-stigma messaging campaigns allow a broad audience to gain a more nuanced understanding of the lives of PwD and their caregivers. These projects are rich resources that offer education and personal stories that can counter common stereotypes about dementia.

Typical Day is a photography project developed and maintained by clinicians and researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. Since early 2017, the project has provided a forum for individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia to document their lives and show what it means to them to live with dementia. Participants in the project photo-document the people, places, and objects that define their daily lives. They review and explain these photos with researchers at Penn Memory Center, who help them tell their stories. The participants’ stories, the photos they capture, and their portraits are available at www.mytypicalday.org.

People of Dementia. Storytelling is a powerful way to raise awareness of and reduce the stigma associated with dementia. For PwD, telling their stories can be an effective and therapeutic way to communicate their emotions and deliver an important message. In the blog People of Dementia (www.peopleofdementia.com),22,23 PwD highlight who they were before the disease and how things have changed, with family members highlighting the challenges of caring for a person with dementia.

Continue to: The common thread is...

The common thread is the enduring “person” behind the exterior that is obscured by dementia. By allowing the audience to form a connection with who the individual was prior to the disease, and understanding the changes that have come as a result of dementia to both PwD and their support network, readers gain a greater appreciation of those affected by dementia. Between May 1, 2017 and May 31, 2019, the blog had more than 3,860 visitors. In an accompanying online survey (N = 57), 79% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that after visiting the People of Dementia blog, they had a better understanding of the changes that occur as a result of cognitive impairment/dementia (Figure 1). Almost two-thirds of respondents (65%) agreed/strongly agreed that they felt more comfortable interacting with PwD (Figure 2). Additionally, 60% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that they were more encouraged to work with PwD, and 90% agreed/strongly agreed that they had a greater appreciation of the challenges of being a caregiver for PwD. Overall, these findings suggest that the People of Dementia blog is useful for engaging the public and promoting a better understanding of dementia.

Work for policy changes

Clinicians can support public policy through education and advocacy both in the delivery of care and as spokespersons and stakeholders in their local communities. Public policies are important for providing access to medical and social services to meet the needs of PwD and their caregivers. The absence—real or perceived—of sufficient resources exacerbates dementia-related stigma. In addition to facilitating access to resources, national dementia strategies or legal frameworks, such as the National Alzheimer’s Project Act in the United States, include policy initiatives to identify and promote communication approaches that are effective and sensitive with respect to people living with dementia and their caregivers.

State and local legislators and patient advocates are leading policy efforts to reduce dementia-related stigma. For example, Colorado recently changed statutory references from being specific to diseases that cause dementia to the broader, more inclusive phrase “dementia diseases and related disabilities.”18 In addition to making funds available to support caregiving services for PwD, this legislative change added training for first responders to better meet the needs of missing PwD, and shifted the terminology used to diagnose and communicate about diseases causing dementia. The shift in language added new terminology that was chosen for being more person-centered to replace prior references to “senior senility,” “senility,” and other terms with pejorative meanings.

In Canada, a National Dementia Strategy will commit the Canadian government to action with definitive timelines, targets, reporting structures, and measurable outcomes.24

Table 2 summarizes approaches to a

Continue to: An open discussion

An open discussion

Larger studies and testing of diverse approaches are needed to better understand whether intergenerational initiatives or other approaches can genuinely modify stigmatizing attitudes in various dementia populations, especially considering language, health literacy, cultural preferences, and other needs. The identified effects on physical and mental health, quality of life, self-esteem, and behavioral symptoms further support the extensive, negative effects of self-stigma on PwD, and emphasize the need to develop and test interventions to ameliorate these effects.

We presented at a Stigma Symposium at the 2018 Gerontological Society of America Annual Scientific Meeting in Boston, Massachusetts.25 Attendees of this conference shared our concerns about the detrimental effects of stigma. The main question we were asked was “What can we do to reduce stigma?” Perhaps the most immediate response is that in order to move the stigma dial, clinicians need to recognize that stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on PwD and their families.6 Bringing the discussion into the open and targeting stigma at multiple levels needs to be addressed by clinicians, researchers, administrators, and society at large.

Bottom Line

Stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on persons with dementia and their families. In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Anti-stigma messaging campaigns and public policy changes also can be used to address societal and social inequities of patients with dementia and their caregivers.

Related Resources

- Khoury R, Shach R, Nair A, et al. Can lifestyle modifications delay or prevent Alzheimer’s disease? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):29-36,38.

- Burke AD, Burke WJ. Antipsychotics for patients with dementia: The road less traveled. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):26-32,35-37.

1. World Health Organization. Towards a dementia plan: a WHO guide. https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/policy_guidance/en/. Published 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

2. Goffman E. Stigma. New York, NY: Prentice-Hall; 1963:1-123.

3. Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2012: overcoming the stigma of dementia. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2012.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed May 28, 2019.

4. Blay SL, Peluso ETP. Public stigma: the community’s tolerance of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):163-171.

5. Piver LC, Nubukpo P, Faure A, et al. Describing perceived stigma against Alzheimer’s disease in a general population in France: the STIG-MA survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(9):933-938.

6. Herrmann LK, Welter E, Leverenz J, et al. A systematic review of dementia-related stigma research: can we move the stigma dial? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):316-331.

7. Eng KJ, Woo BKP. Knowledge of dementia community resources and stigma among Chinese American immigrants. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(1):e3-e4. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.11.003.

8. Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga D. Knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease, feelings of shame, and awareness of services among Korean American elders. J Aging Health. 2010;22(4):419-433.

9. Werner P, Goldstein D, Heinik J. Development and validity of the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s disease scale (FS-ADS). Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2011;25(1):42-48.

10. Rao D, Choi SW, Victorson D, et al. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: the development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI). Qual Life Res. 2009;18(5):585-595.

11. Boustani M, Perkins AJ, Monahan P, et al. Measuring primary care patients’ attitudes about dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(8):812-820.

12. Burgener SC, Buckwalter K, Perkounkova Y, et al. Perceived stigma in persons with early-stage dementia: longitudinal findings: Part 2. Dementia. 2015;14(5):609-632.

13. Burgener SC, Buckwalter K. The effects of perceived stigma on persons with dementia and their family caregivers. In: Symposium on Stigma: It’s time to talk about it. Boston, MA: Gerontological Society of America 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting; 2018. Session 2805.

14. Harper L, Dobbs B, Royan H, et al. The experience of stigma in care partners of people with dementia – results from an exploratory study. In Symposium on stigma: it’s time to talk about it. Boston, MA: Gerontological Society of America 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting; 2018. Session 2805.

15. Burgener S, Berger B. Measuring perceived stigma in persons with progressive neurological disease: Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson disease. Dementia. 2008;7(1):31-53.

16. Stites SD, Milne R, Karlawish J. Advances in Alzheimer’s imaging are changing the experience of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018;10;285-300.

17. Anderson LA, Egge R. Expanding efforts to address Alzheimer’s disease: the Healthy Brain Initiative. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014;10(50):S453-S456.

18. Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup. Report on the milestones for the US National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2014;10(Suppl 5);S430-S452. doi:10.1016/j/jalz.2014.08.103.

19. Kirkman AM. Dementia in the news: the media coverage of Alzheimer’s disease. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2006;25(2):74-79.

20. Swaffer, K. Dementia: stigma, language, and dementia-friendly. Dementia. 2014;13(6):709-716.

21. Stites SD, Karlawish J. Stigma of Alzheimer’s disease dementia: considerations for practice. Practical Neurology. https://practicalneurology.com/articles/2018-june/stigma-of-alzheimers-disease-dementia. Published June 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

22. Jamieson J, Dobbs B, Charles L, et al. Forgetful, but not forgotten people of dementia: a novel, technology focused project with a humanistic touch. Geriatric Grand Rounds; October 10, 2017. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

23. Dobbs B, Charles L, Chan K, et al. People of Dementia. CGS 37th Annual Scientific Meeting: Integrating Care, Making an Impact. Can Geriatr J. 2017;20(3):220.

24. Government of Canada. Conference report: National Dementia Conference. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/publications/diseases-conditions/national-dementia-conference-report.html. Government of Canada. Published August 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.