Results

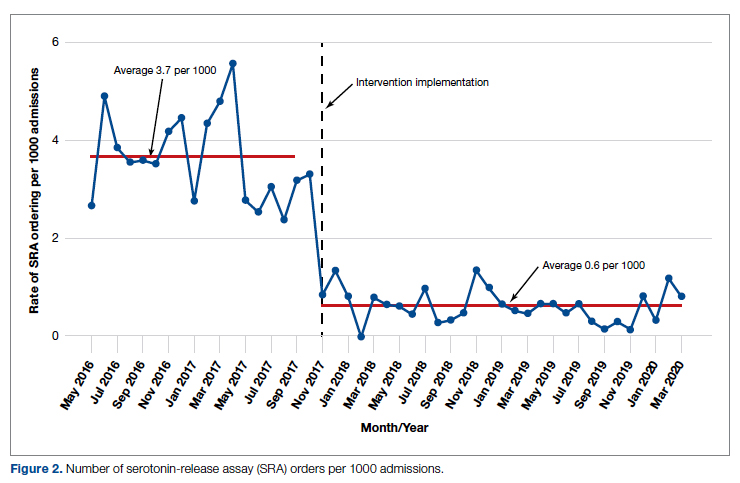

During the pre-intervention period, the average number of admissions (adults and children) at UM was 5863 per month. Post intervention there was an average of 5842 admissions per month. A total of 1192 PF4 tests were ordered before the intervention and 1148 were ordered post intervention. Prior to the intervention, 481 SRA tests were completed, while post intervention 105 were completed. Serotonin-release testing decreased from an average of 3.7 SRA results per 1000 admissions during the pre-intervention period to an average of 0.6 per 1000 admissions post intervention (Figure 2). Cost-savings were $1045 per 1000 admissions.

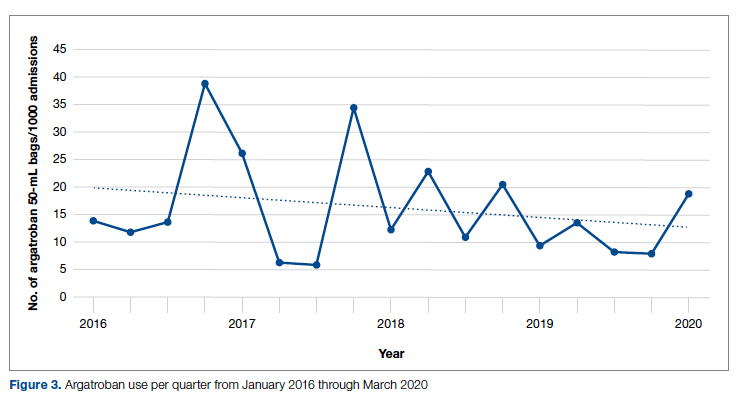

During the pre-intervention period, 2539 bags of argatroban were used, while 2337 bags were used post intervention. The number of 50-mL argatroban bags used per 1000 admissions decreased from 18.8 before the intervention to 14.3 post intervention. Cost-savings were $1316.20 per 1000 admissions. Figure 3 illustrates the monthly argatroban utilization per 1000 admissions during each quarter from January 2016 through March 2020.

Discussion

We designed and implemented an evidence-based strategy for HIT at our academic institution which led to a decrease in unnecessary SRA testing and argatroban utilization, with associated cost savings. By focusing on a single point of intervention at the laboratory level where SRA tests were held and canceled if the PF4 test was negative, we helped offload the decision-making from the provider while simultaneously providing just-in-time education to the provider. This intervention was designed with input from multiple stakeholders, including physicians, quality improvement specialists, pharmacists, and coagulation laboratory personnel.

Serotonin-release testing dramatically decreased post intervention even though a similar number of PF4 tests were performed before and after the intervention. This suggests that the decrease in SRA testing was a direct consequence of our intervention. Post intervention the number of completed SRA tests was 9% of the number of PF4 tests sent. This is consistent with our baseline pre-intervention data showing that only 8% of all PF4 tests sent were positive.

While the absolute number of argatroban bags utilized did not dramatically decrease after the intervention, the quarterly rate did, particularly after 2018. Given that argatroban data were only drawn from patients with a concurrent SRA test, this decrease is clearly from decreased usage in patients with suspected HIT. We suspect the decrease occurred because argatroban was not being continued while awaiting an SRA test in patients with a negative PF4 test. Decreasing the utilization of argatroban not only saved money but also reduced days of exposure to argatroban. While we do not have data regarding adverse events related to argatroban prior to the intervention, it is logical to conclude that reducing unnecessary exposure to argatroban reduces the risk of adverse events related to bleeding. Future studies would ideally address specific safety outcome metrics such as adverse events, bleeding risk, or missed diagnoses of HIT.

Our institutional guidelines for the diagnosis of HIT are evidence-based and helpful but are rarely followed by busy inpatient providers. Controlling the utilization of the SRA at the laboratory level had several advantages. First, removing SRA decision-making from providers who are not experts in the diagnosis of HIT guaranteed adherence to evidence-based guidelines. Second, pharmacists could safely recommend discontinuing argatroban when the PF4 test was negative as there was no SRA pending. Third, with cancellation at the laboratory level there was no need to further burden providers with yet another alert in the electronic health record. Fourth, just-in-time education was provided to the providers with justification for why the SRA test was canceled. Last, ruling out HIT within 24 hours with the PF4 test alone allowed providers to evaluate patients for other causes of thrombocytopenia much earlier than the 3 to 5 business days before the SRA results returned.

A limitation of this study is that it was conducted at a single center. Our approach is also limited by the lack of universal applicability. At our institution we are fortunate to have PF4 testing available in our coagulation laboratory 7 days a week. In addition, the coagulation laboratory controls sending the SRA to the reference laboratory. The specific intervention of controlling the SRA testing is therefore applicable only to institutions similar to ours; however, the concept of removing control of specialized testing from the provider is not unique. Inpatient thrombophilia testing has been a successful target of this approach.11-13 While electronic alerts and education of individual providers can also be effective initially, the effectiveness of these interventions has been repeatedly shown to wane over time.14-16

Conclusion

At our institution we were able to implement practical, evidence-based testing for HIT by implementing control over SRA testing at the level of the laboratory. This approach led to decreased argatroban utilization and cost savings.

Corresponding author: Alice Cusick, MD; LTC Charles S Kettles VA Medical Center, 2215 Fuller Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48105; mccoyag@med.umich.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

doi: 10.12788/jcom.0087