From the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System Medicine Service (Dr. Cusick), University of Michigan College of Pharmacy, Clinical Pharmacy Service, Michigan Medicine (Dr. Hanigan), Department of Internal Medicine Clinical Experience and Quality, Michigan Medicine (Linda Bashaw), Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI (Dr. Heidemann), and the Operational Excellence Department, Sparrow Health System, Lansing, MI (Matthew Johnson).

Abstract

Background: Diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) requires completion of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)–based heparin-platelet factor 4 (PF4) antibody test. If this test is negative, HIT is excluded. If positive, a serotonin-release assay (SRA) test is indicated. The SRA is expensive and sometimes inappropriately ordered despite negative PF4 results, leading to unnecessary treatment with argatroban while awaiting SRA results.

Objectives: The primary objectives of this project were to reduce unnecessary SRA testing and argatroban utilization in patients with suspected HIT.

Methods: The authors implemented an intervention at a tertiary care academic hospital in November 2017 targeting patients hospitalized with suspected HIT. The intervention was controlled at the level of the laboratory and prevented ordering of SRA tests in the absence of a positive PF4 test. The number of SRA tests performed and argatroban bags administered were identified retrospectively via chart review before the intervention (January 2016 to November 2017) and post intervention (December 2017 to March 2020). Associated costs were calculated based on institutional SRA testing cost as well as the average wholesale price of argatroban.

Results: SRA testing decreased from an average of 3.7 SRA results per 1000 admissions before the intervention to an average of 0.6 results per 1000 admissions post intervention. The number of 50-mL argatroban bags used per 1000 admissions decreased from 18.8 prior to the intervention to 14.3 post intervention. Total estimated cost savings per 1000 admissions was $2361.20.

Conclusion: An evidence-based testing strategy for HIT can be effectively implemented at the level of the laboratory. This approach led to reductions in SRA testing and argatroban utilization with resultant cost savings.

Keywords: HIT, argatroban, anticoagulation, serotonin-release assay.

Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in hospitalized patients.1,2 Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is one of the many potential causes of thrombocytopenia in hospitalized patients and occurs when antibodies to the heparin-platelet factor 4 (PF4) complex develop after heparin exposure. This triggers a cascade of events, leading to platelet activation, platelet consumption, and thrombosis. While HIT is relatively rare, occurring in 0.3% to 0.5% of critically ill patients, many patients will be tested to rule out this potentially life-threatening cause of thrombocytopenia.3

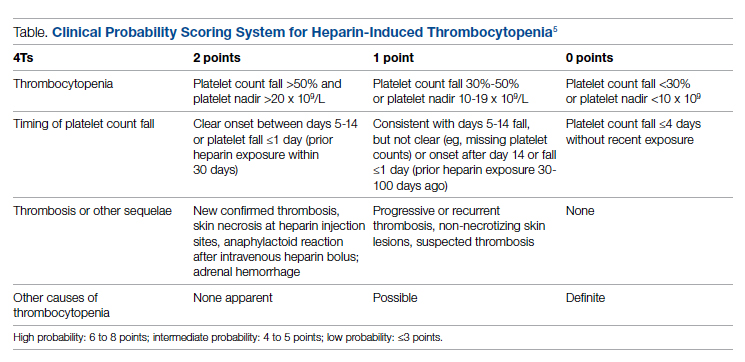

The diagnosis of HIT utilizes a combination of both clinical suspicion and laboratory testing.4 The 4T score (Table) was developed to evaluate the clinical probability of HIT and involves assessing the degree and timing of thrombocytopenia, the presence or absence of thrombosis, and other potential causes of the thrombocytopenia.5 The 4T score is designed to be utilized to identify patients who require laboratory testing for HIT; however, it has low inter-rater agreement in patients undergoing evaluation for HIT,6 and, in our experience, completion of this scoring is time-consuming.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a commonly used laboratory test to diagnose HIT that detects antibodies to the heparin-PF4 complex utilizing optical density (OD) units. When using an OD cutoff of 0.400, ELISA PF4 (PF4) tests have a sensitivity of 99.6%, but poor specificity at 69.3%.7 When the PF4 antibody test is positive with an OD ≥0.400, then a functional test is used to determine whether the antibodies detected will activate platelets. The serotonin-release assay (SRA) is a functional test that measures 14C-labeled serotonin release from donor platelets when mixed with patient serum or plasma containing HIT antibodies. In the correct clinical context, a positive ELISA PF4 antibody test along with a positive SRA is diagnostic of HIT.8

The process of diagnosing HIT in a timely and cost-effective manner is dependent on the clinician’s experience in diagnosing HIT as well as access to the laboratory testing necessary to confirm the diagnosis. PF4 antibody tests are time-consuming and not always available daily and/or are not available onsite. The SRA requires access to donor platelets and specialized radioactivity counting equipment, making it available only at particular centers.

The treatment of HIT is more straightforward and involves stopping all heparin products and starting a nonheparin anticoagulant. The direct thrombin inhibitor argatroban is one of the standard nonheparin anticoagulants used in patients with suspected HIT.4 While it is expensive, its short half-life and lack of renal clearance make it ideal for treatment of hospitalized patients with suspected HIT, many of whom need frequent procedures and/or have renal disease.

At our academic tertiary care center, we performed a retrospective analysis that showed inappropriate ordering of diagnostic HIT testing as well as unnecessary use of argatroban even when there was low suspicion for HIT based on laboratory findings. The aim of our project was to reduce unnecessary HIT testing and argatroban utilization without overburdening providers or interfering with established workflows.