User login

ACS NSQIP pilot project IDs risks in older surgical patients

NEW YORK – The American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Improvement Program Geriatric Surgery Pilot Project, which was initiated in 2014, is beginning to bear fruit.

Institutions participating in the project are generating data on geriatric-specific factors such as cognition and mobility that have been shown to add to standard risks associated with surgery in older adults.

“Before you operate at all, there is a decision, and often surgeons use this framework when deciding whether or not to operate: There is an isolated surgical problem, and I think we can fix that problem,” Julia R. Berian, MD, said at the ACS Quality and Safety Conference. “This fails to really incorporate the context of these older, complicated surgical patients.”

“We are facing a silver tsunami. The population is aging,” Emily Finlayson, MD, FACS, said during a separate presentation at the conference. “People are coming to us to decide, A, if they should have surgery, and B, how best to prepare for surgery.”

“As we know, from mounting evidence, surgical outcomes in frail older adults are pretty abysmal.” In addition to the physiologic vulnerabilities, “there is a lot of social isolation, depression, and anxiety that is underdiagnosed in this population,” Dr. Finlayson said. “In light of these incredibly high risks, we need to approach decision making in a slightly different way than we do with, say, a 40-year-old patient.”

Use data to guide interventions

The ACS NSQIP and the ACS Geriatric Task Force created the ACS NSQIP Geriatric Surgery Pilot Project in part to determine if including geriatric-specific preoperative variables and outcome measures in the NSQIP database would improve postoperative outcomes. Since its launch in January 2014, more than 30 hospitals have contributed data from over 30,000 surgical cases involving patients 65 years and older. The vast majority of cases involve orthopedic surgery or general surgery, with total hip and total knee arthroplasty, colectomy, spine surgery, and hip fracture procedures leading the list.

Cognition, function, mobility, and goals/decision making are the four main project domains. “The event rate for postoperative delirium overall was 12%; the functional decline was quite high at 43%; and the need for postoperative mobility aid was 30%,” said Dr. Berian, a fourth-year general surgery resident at the University of Chicago and an ACS Clinical Scholar, when presenting initial 3-year results.

“What we have learned from this experience is that these geriatric-specific risk factors do contribute to risk adjustment for traditional morbidity and mortality outcomes. In other words, we think they are very important to collect,” Dr. Berian said.

Cognitive impairment was associated only with prolonged ventilation, whereas surrogate consent for surgery correlated with any morbidity, reintubation, pneumonia, and more. Use of a mobility aid before surgery correlated with increased risk for a UTI, surgical site infection, sepsis, and other morbidities. A history of falls within the previous year was associated with higher risk of cardiac complications and mortality. Functional status, origin from home before surgery, and use of preoperative palliative care were not contributors to risk.

A second objective of the project is to create a platform for introducing interventions to improve outcomes in this population. Future plans include further validation of the pilot data and incorporation of the results into a geriatric-specific quality program.

Focus on potential solutions

Addressing a wide range of preoperative considerations in older adults may seem daunting, but “there are simple, low-tech things you can do,” said Dr. Finlayson, director of the University of California San Francisco Center for Surgery in Older Adults. Strategies include reviewing medications, providing adequate hydration “so they don’t come in as dry as a potato chip,” and removing earwax. “You might think they’re confused but they really cannot hear.”

Whenever possible, address the core vulnerabilities that put an older patient at higher risk, Dr. Finlayson said. Comorbidity, polypharmacy, incontinence, social isolation, depression and anxiety, as well as deficits in function, nutrition, and mobility can contribute.

Cognition is also critical. If you think an older patient is at risk of postoperative delirium, involve the family, Dr. Finlayson recommended. “We know if family members are at the bedside, the patient is less likely to get confused.” Clinicians at UCSF found this “very helpful” and even give families a sign-up sheet to assign shifts in the hospital.

“If you don’t think delirium is an important outcome to begin tracking in our registries, I want to point out that there are serious consequences for postop delirium,” Dr. Berian said. Delirium alone in surgical patients doubles the increased risk of prolonged length of stay, 1.5 times the risk for institutional discharge, and 2.3 times the risk for 30-day readmission (JAMA Surgery. 2015;150[12]:1134-40). “When you combine delirium with complications, those risks increase dramatically,” she added.

Take a team approach

Session moderator David A. Hoyt, MD, FACS, executive director of the American College of Surgeons, asked Dr. Finlayson how she convinced her colleagues to participate in the program at UCSF.

“We haven’t had any problems with buy-in in terms of recognizing the need,” she replied. “The challenge is a lot of surgeons feel like they don’t have the expertise or the time to slow down and learn how to do these assessments and optimization strategies.” She suggested involving geriatricians and other providers when possible. “You have to be very creative within your own system in terms of what kind of team you are going to put together.”

Elicit patient goals

Perhaps most importantly, you really need to individualize your approach, Dr. Finlayson said. Take the time to talk to these patients. “This isn’t just don’t smoke, lose weight, diet and exercise. It’s eliciting patient goals and tailoring an assessment of geriatric vulnerability,” she added. “It’s not one size fits all. It’s not just about fitness for surgery; it’s about what they want for the rest of their lives.”

Patient-driven goals are important, Dr. Berian said, because “older adults may prioritize quality of life over quantity of life.” She also noted that surgery could cure their disease, prolong life, and/or provide symptom relief, or it could cause loss of function and independence, delirium, cognitive loss, and/or premature death. “There was an interesting study … looking at outcomes that could be considered worse than death,” Dr. Berian said (JAMA Intern. Med. 2016;176[10]:1557-9). Bowel and bladder incontinence, being confused all the time, and relying on a feeding tube to live were among the outcomes the researchers examined.

Dr. Finlayson highlighted a high-touch, resource-intensive, and successful intervention in older patients in the United Kingdom (Age Ageing. 2007;36[6]:670-5). “The reduction in morbidity was incredibly dramatic.” The study shows if you truly have the resources to address these geriatric syndromes, you can really improve care in this population.

Dr. Berian had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Finlayson is a founding shareholder of Ooney, Inc.

NEW YORK – The American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Improvement Program Geriatric Surgery Pilot Project, which was initiated in 2014, is beginning to bear fruit.

Institutions participating in the project are generating data on geriatric-specific factors such as cognition and mobility that have been shown to add to standard risks associated with surgery in older adults.

“Before you operate at all, there is a decision, and often surgeons use this framework when deciding whether or not to operate: There is an isolated surgical problem, and I think we can fix that problem,” Julia R. Berian, MD, said at the ACS Quality and Safety Conference. “This fails to really incorporate the context of these older, complicated surgical patients.”

“We are facing a silver tsunami. The population is aging,” Emily Finlayson, MD, FACS, said during a separate presentation at the conference. “People are coming to us to decide, A, if they should have surgery, and B, how best to prepare for surgery.”

“As we know, from mounting evidence, surgical outcomes in frail older adults are pretty abysmal.” In addition to the physiologic vulnerabilities, “there is a lot of social isolation, depression, and anxiety that is underdiagnosed in this population,” Dr. Finlayson said. “In light of these incredibly high risks, we need to approach decision making in a slightly different way than we do with, say, a 40-year-old patient.”

Use data to guide interventions

The ACS NSQIP and the ACS Geriatric Task Force created the ACS NSQIP Geriatric Surgery Pilot Project in part to determine if including geriatric-specific preoperative variables and outcome measures in the NSQIP database would improve postoperative outcomes. Since its launch in January 2014, more than 30 hospitals have contributed data from over 30,000 surgical cases involving patients 65 years and older. The vast majority of cases involve orthopedic surgery or general surgery, with total hip and total knee arthroplasty, colectomy, spine surgery, and hip fracture procedures leading the list.

Cognition, function, mobility, and goals/decision making are the four main project domains. “The event rate for postoperative delirium overall was 12%; the functional decline was quite high at 43%; and the need for postoperative mobility aid was 30%,” said Dr. Berian, a fourth-year general surgery resident at the University of Chicago and an ACS Clinical Scholar, when presenting initial 3-year results.

“What we have learned from this experience is that these geriatric-specific risk factors do contribute to risk adjustment for traditional morbidity and mortality outcomes. In other words, we think they are very important to collect,” Dr. Berian said.

Cognitive impairment was associated only with prolonged ventilation, whereas surrogate consent for surgery correlated with any morbidity, reintubation, pneumonia, and more. Use of a mobility aid before surgery correlated with increased risk for a UTI, surgical site infection, sepsis, and other morbidities. A history of falls within the previous year was associated with higher risk of cardiac complications and mortality. Functional status, origin from home before surgery, and use of preoperative palliative care were not contributors to risk.

A second objective of the project is to create a platform for introducing interventions to improve outcomes in this population. Future plans include further validation of the pilot data and incorporation of the results into a geriatric-specific quality program.

Focus on potential solutions

Addressing a wide range of preoperative considerations in older adults may seem daunting, but “there are simple, low-tech things you can do,” said Dr. Finlayson, director of the University of California San Francisco Center for Surgery in Older Adults. Strategies include reviewing medications, providing adequate hydration “so they don’t come in as dry as a potato chip,” and removing earwax. “You might think they’re confused but they really cannot hear.”

Whenever possible, address the core vulnerabilities that put an older patient at higher risk, Dr. Finlayson said. Comorbidity, polypharmacy, incontinence, social isolation, depression and anxiety, as well as deficits in function, nutrition, and mobility can contribute.

Cognition is also critical. If you think an older patient is at risk of postoperative delirium, involve the family, Dr. Finlayson recommended. “We know if family members are at the bedside, the patient is less likely to get confused.” Clinicians at UCSF found this “very helpful” and even give families a sign-up sheet to assign shifts in the hospital.

“If you don’t think delirium is an important outcome to begin tracking in our registries, I want to point out that there are serious consequences for postop delirium,” Dr. Berian said. Delirium alone in surgical patients doubles the increased risk of prolonged length of stay, 1.5 times the risk for institutional discharge, and 2.3 times the risk for 30-day readmission (JAMA Surgery. 2015;150[12]:1134-40). “When you combine delirium with complications, those risks increase dramatically,” she added.

Take a team approach

Session moderator David A. Hoyt, MD, FACS, executive director of the American College of Surgeons, asked Dr. Finlayson how she convinced her colleagues to participate in the program at UCSF.

“We haven’t had any problems with buy-in in terms of recognizing the need,” she replied. “The challenge is a lot of surgeons feel like they don’t have the expertise or the time to slow down and learn how to do these assessments and optimization strategies.” She suggested involving geriatricians and other providers when possible. “You have to be very creative within your own system in terms of what kind of team you are going to put together.”

Elicit patient goals

Perhaps most importantly, you really need to individualize your approach, Dr. Finlayson said. Take the time to talk to these patients. “This isn’t just don’t smoke, lose weight, diet and exercise. It’s eliciting patient goals and tailoring an assessment of geriatric vulnerability,” she added. “It’s not one size fits all. It’s not just about fitness for surgery; it’s about what they want for the rest of their lives.”

Patient-driven goals are important, Dr. Berian said, because “older adults may prioritize quality of life over quantity of life.” She also noted that surgery could cure their disease, prolong life, and/or provide symptom relief, or it could cause loss of function and independence, delirium, cognitive loss, and/or premature death. “There was an interesting study … looking at outcomes that could be considered worse than death,” Dr. Berian said (JAMA Intern. Med. 2016;176[10]:1557-9). Bowel and bladder incontinence, being confused all the time, and relying on a feeding tube to live were among the outcomes the researchers examined.

Dr. Finlayson highlighted a high-touch, resource-intensive, and successful intervention in older patients in the United Kingdom (Age Ageing. 2007;36[6]:670-5). “The reduction in morbidity was incredibly dramatic.” The study shows if you truly have the resources to address these geriatric syndromes, you can really improve care in this population.

Dr. Berian had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Finlayson is a founding shareholder of Ooney, Inc.

NEW YORK – The American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Improvement Program Geriatric Surgery Pilot Project, which was initiated in 2014, is beginning to bear fruit.

Institutions participating in the project are generating data on geriatric-specific factors such as cognition and mobility that have been shown to add to standard risks associated with surgery in older adults.

“Before you operate at all, there is a decision, and often surgeons use this framework when deciding whether or not to operate: There is an isolated surgical problem, and I think we can fix that problem,” Julia R. Berian, MD, said at the ACS Quality and Safety Conference. “This fails to really incorporate the context of these older, complicated surgical patients.”

“We are facing a silver tsunami. The population is aging,” Emily Finlayson, MD, FACS, said during a separate presentation at the conference. “People are coming to us to decide, A, if they should have surgery, and B, how best to prepare for surgery.”

“As we know, from mounting evidence, surgical outcomes in frail older adults are pretty abysmal.” In addition to the physiologic vulnerabilities, “there is a lot of social isolation, depression, and anxiety that is underdiagnosed in this population,” Dr. Finlayson said. “In light of these incredibly high risks, we need to approach decision making in a slightly different way than we do with, say, a 40-year-old patient.”

Use data to guide interventions

The ACS NSQIP and the ACS Geriatric Task Force created the ACS NSQIP Geriatric Surgery Pilot Project in part to determine if including geriatric-specific preoperative variables and outcome measures in the NSQIP database would improve postoperative outcomes. Since its launch in January 2014, more than 30 hospitals have contributed data from over 30,000 surgical cases involving patients 65 years and older. The vast majority of cases involve orthopedic surgery or general surgery, with total hip and total knee arthroplasty, colectomy, spine surgery, and hip fracture procedures leading the list.

Cognition, function, mobility, and goals/decision making are the four main project domains. “The event rate for postoperative delirium overall was 12%; the functional decline was quite high at 43%; and the need for postoperative mobility aid was 30%,” said Dr. Berian, a fourth-year general surgery resident at the University of Chicago and an ACS Clinical Scholar, when presenting initial 3-year results.

“What we have learned from this experience is that these geriatric-specific risk factors do contribute to risk adjustment for traditional morbidity and mortality outcomes. In other words, we think they are very important to collect,” Dr. Berian said.

Cognitive impairment was associated only with prolonged ventilation, whereas surrogate consent for surgery correlated with any morbidity, reintubation, pneumonia, and more. Use of a mobility aid before surgery correlated with increased risk for a UTI, surgical site infection, sepsis, and other morbidities. A history of falls within the previous year was associated with higher risk of cardiac complications and mortality. Functional status, origin from home before surgery, and use of preoperative palliative care were not contributors to risk.

A second objective of the project is to create a platform for introducing interventions to improve outcomes in this population. Future plans include further validation of the pilot data and incorporation of the results into a geriatric-specific quality program.

Focus on potential solutions

Addressing a wide range of preoperative considerations in older adults may seem daunting, but “there are simple, low-tech things you can do,” said Dr. Finlayson, director of the University of California San Francisco Center for Surgery in Older Adults. Strategies include reviewing medications, providing adequate hydration “so they don’t come in as dry as a potato chip,” and removing earwax. “You might think they’re confused but they really cannot hear.”

Whenever possible, address the core vulnerabilities that put an older patient at higher risk, Dr. Finlayson said. Comorbidity, polypharmacy, incontinence, social isolation, depression and anxiety, as well as deficits in function, nutrition, and mobility can contribute.

Cognition is also critical. If you think an older patient is at risk of postoperative delirium, involve the family, Dr. Finlayson recommended. “We know if family members are at the bedside, the patient is less likely to get confused.” Clinicians at UCSF found this “very helpful” and even give families a sign-up sheet to assign shifts in the hospital.

“If you don’t think delirium is an important outcome to begin tracking in our registries, I want to point out that there are serious consequences for postop delirium,” Dr. Berian said. Delirium alone in surgical patients doubles the increased risk of prolonged length of stay, 1.5 times the risk for institutional discharge, and 2.3 times the risk for 30-day readmission (JAMA Surgery. 2015;150[12]:1134-40). “When you combine delirium with complications, those risks increase dramatically,” she added.

Take a team approach

Session moderator David A. Hoyt, MD, FACS, executive director of the American College of Surgeons, asked Dr. Finlayson how she convinced her colleagues to participate in the program at UCSF.

“We haven’t had any problems with buy-in in terms of recognizing the need,” she replied. “The challenge is a lot of surgeons feel like they don’t have the expertise or the time to slow down and learn how to do these assessments and optimization strategies.” She suggested involving geriatricians and other providers when possible. “You have to be very creative within your own system in terms of what kind of team you are going to put together.”

Elicit patient goals

Perhaps most importantly, you really need to individualize your approach, Dr. Finlayson said. Take the time to talk to these patients. “This isn’t just don’t smoke, lose weight, diet and exercise. It’s eliciting patient goals and tailoring an assessment of geriatric vulnerability,” she added. “It’s not one size fits all. It’s not just about fitness for surgery; it’s about what they want for the rest of their lives.”

Patient-driven goals are important, Dr. Berian said, because “older adults may prioritize quality of life over quantity of life.” She also noted that surgery could cure their disease, prolong life, and/or provide symptom relief, or it could cause loss of function and independence, delirium, cognitive loss, and/or premature death. “There was an interesting study … looking at outcomes that could be considered worse than death,” Dr. Berian said (JAMA Intern. Med. 2016;176[10]:1557-9). Bowel and bladder incontinence, being confused all the time, and relying on a feeding tube to live were among the outcomes the researchers examined.

Dr. Finlayson highlighted a high-touch, resource-intensive, and successful intervention in older patients in the United Kingdom (Age Ageing. 2007;36[6]:670-5). “The reduction in morbidity was incredibly dramatic.” The study shows if you truly have the resources to address these geriatric syndromes, you can really improve care in this population.

Dr. Berian had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Finlayson is a founding shareholder of Ooney, Inc.

AT THE ACS QUALITY AND SAFETY CONFERENCE

Immobility implicated in increased complications after bariatric surgery

NEW YORK –

“The importance of this study is to help us as an institution, but then also nationally, to try to focus on quality initiatives to improve the complication rate and safety profile of these patients, who are incredibly high risk for bariatric surgery,” said Rana Higgins, MD, a general surgeon at Froedtert Hospital and the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

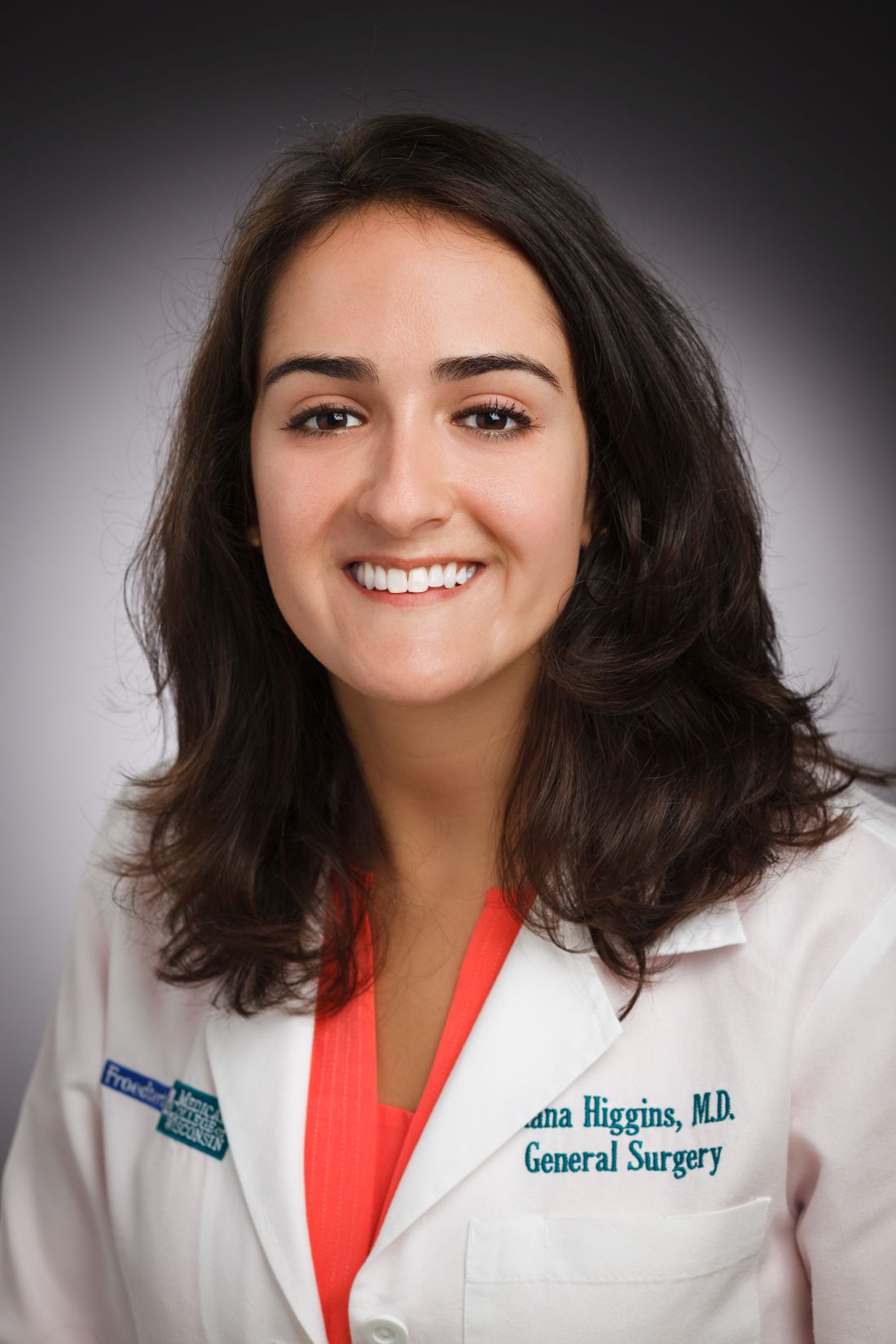

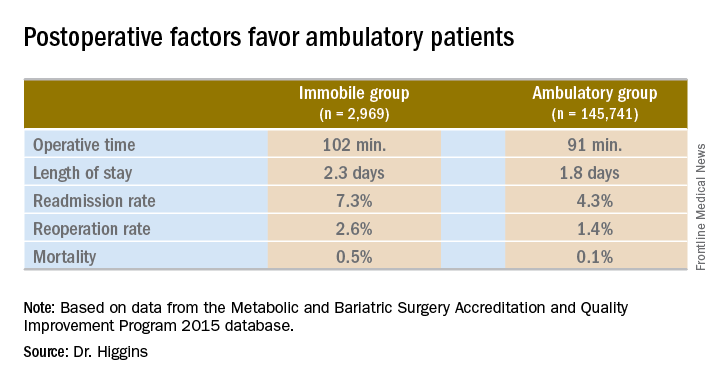

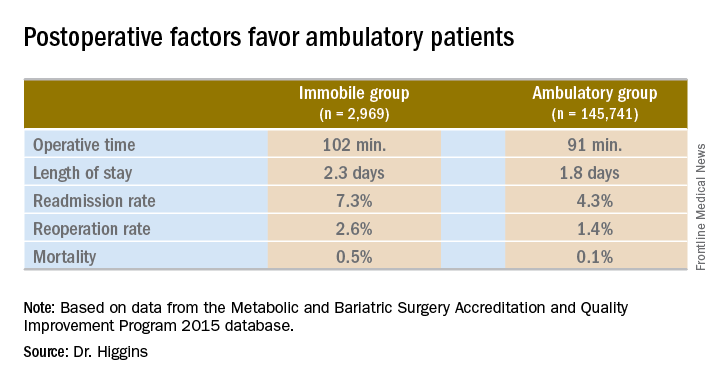

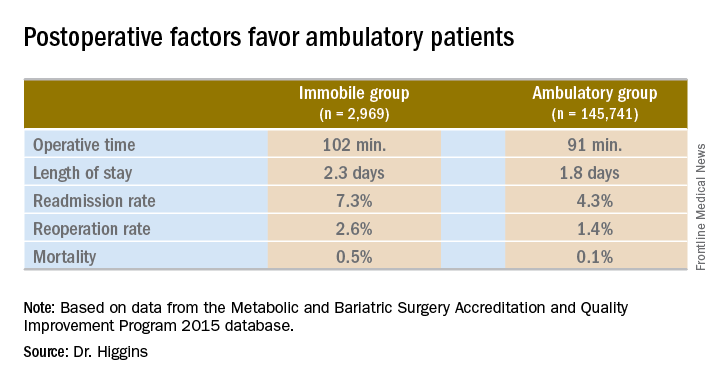

Dr. Higgins and her colleagues compared 2,969 immobile patients with 145,741 who were ambulatory before surgery. The most common bariatric procedure was sleeve gastrectomy at 56%. Another 30% had gastric bypass, 3% had the gastric band, and the remaining 1% underwent other procedures, such as biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. The MBSAQIP (Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program) defines immobility as a patient with limited ambulation who requires assistive devices, such as a scooter or wheelchair, to ambulate most or all of the time. In addition, with regard to negotiating stairs, immobile patients need a home lift or an elevator.

Only three complications evaluated by the researchers were not statistically different between groups: intraoperative or postoperative coma, stroke, and myocardial infarction.

Operative time was longer in the immobile group, about 102 minutes vs. 91 minutes (P less than .001). A meeting attendee asked what accounted for the difference. Dr. Higgins replied, “We’ll have to go back and look at our data. My hypothesis is that the immobile patients had a higher BMI [body mass index]. They may also have had other comorbidities that contributed to increased operative time.”

Hospital length of stay was also significantly longer among immobile patients at 2.3 days vs. 1.8 days in the ambulatory group (P less than .001).

The readmission rate was higher among immobile patients – 7.3% vs. 4.3% for the ambulatory group. The reoperation rate was higher at 2.6% vs. 1.4%. Both these findings were statistically significant as well (P less than .001).

Immobile patients had a statistically higher risk of mortality at 0.5%, compared with 0.1% among ambulatory patients (OR, 4.6).

A meeting attendee asked Dr. Higgins if her institution addresses mobility issues. She replied that there is preoperative education about the importance of ambulation, but the interventions are focused on ambulation in the postoperative period. “We order physical therapy, immediately postoperatively; typically the patients will receive it that day or the next day. We make sure patients are up and moving as much as possible, but there are limitations if they have limited mobility.”

The same attendee suggested preoperative physical therapy could help, even if only 2-4 weeks prior to surgery. Dr. Higgins agreed that would be a good quality initiative to explore in the future.

She had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK –

“The importance of this study is to help us as an institution, but then also nationally, to try to focus on quality initiatives to improve the complication rate and safety profile of these patients, who are incredibly high risk for bariatric surgery,” said Rana Higgins, MD, a general surgeon at Froedtert Hospital and the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

Dr. Higgins and her colleagues compared 2,969 immobile patients with 145,741 who were ambulatory before surgery. The most common bariatric procedure was sleeve gastrectomy at 56%. Another 30% had gastric bypass, 3% had the gastric band, and the remaining 1% underwent other procedures, such as biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. The MBSAQIP (Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program) defines immobility as a patient with limited ambulation who requires assistive devices, such as a scooter or wheelchair, to ambulate most or all of the time. In addition, with regard to negotiating stairs, immobile patients need a home lift or an elevator.

Only three complications evaluated by the researchers were not statistically different between groups: intraoperative or postoperative coma, stroke, and myocardial infarction.

Operative time was longer in the immobile group, about 102 minutes vs. 91 minutes (P less than .001). A meeting attendee asked what accounted for the difference. Dr. Higgins replied, “We’ll have to go back and look at our data. My hypothesis is that the immobile patients had a higher BMI [body mass index]. They may also have had other comorbidities that contributed to increased operative time.”

Hospital length of stay was also significantly longer among immobile patients at 2.3 days vs. 1.8 days in the ambulatory group (P less than .001).

The readmission rate was higher among immobile patients – 7.3% vs. 4.3% for the ambulatory group. The reoperation rate was higher at 2.6% vs. 1.4%. Both these findings were statistically significant as well (P less than .001).

Immobile patients had a statistically higher risk of mortality at 0.5%, compared with 0.1% among ambulatory patients (OR, 4.6).

A meeting attendee asked Dr. Higgins if her institution addresses mobility issues. She replied that there is preoperative education about the importance of ambulation, but the interventions are focused on ambulation in the postoperative period. “We order physical therapy, immediately postoperatively; typically the patients will receive it that day or the next day. We make sure patients are up and moving as much as possible, but there are limitations if they have limited mobility.”

The same attendee suggested preoperative physical therapy could help, even if only 2-4 weeks prior to surgery. Dr. Higgins agreed that would be a good quality initiative to explore in the future.

She had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK –

“The importance of this study is to help us as an institution, but then also nationally, to try to focus on quality initiatives to improve the complication rate and safety profile of these patients, who are incredibly high risk for bariatric surgery,” said Rana Higgins, MD, a general surgeon at Froedtert Hospital and the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

Dr. Higgins and her colleagues compared 2,969 immobile patients with 145,741 who were ambulatory before surgery. The most common bariatric procedure was sleeve gastrectomy at 56%. Another 30% had gastric bypass, 3% had the gastric band, and the remaining 1% underwent other procedures, such as biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. The MBSAQIP (Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program) defines immobility as a patient with limited ambulation who requires assistive devices, such as a scooter or wheelchair, to ambulate most or all of the time. In addition, with regard to negotiating stairs, immobile patients need a home lift or an elevator.

Only three complications evaluated by the researchers were not statistically different between groups: intraoperative or postoperative coma, stroke, and myocardial infarction.

Operative time was longer in the immobile group, about 102 minutes vs. 91 minutes (P less than .001). A meeting attendee asked what accounted for the difference. Dr. Higgins replied, “We’ll have to go back and look at our data. My hypothesis is that the immobile patients had a higher BMI [body mass index]. They may also have had other comorbidities that contributed to increased operative time.”

Hospital length of stay was also significantly longer among immobile patients at 2.3 days vs. 1.8 days in the ambulatory group (P less than .001).

The readmission rate was higher among immobile patients – 7.3% vs. 4.3% for the ambulatory group. The reoperation rate was higher at 2.6% vs. 1.4%. Both these findings were statistically significant as well (P less than .001).

Immobile patients had a statistically higher risk of mortality at 0.5%, compared with 0.1% among ambulatory patients (OR, 4.6).

A meeting attendee asked Dr. Higgins if her institution addresses mobility issues. She replied that there is preoperative education about the importance of ambulation, but the interventions are focused on ambulation in the postoperative period. “We order physical therapy, immediately postoperatively; typically the patients will receive it that day or the next day. We make sure patients are up and moving as much as possible, but there are limitations if they have limited mobility.”

The same attendee suggested preoperative physical therapy could help, even if only 2-4 weeks prior to surgery. Dr. Higgins agreed that would be a good quality initiative to explore in the future.

She had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ACS QUALITY & SAFETY CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Patients immobile before bariatric surgery could require closer monitoring for postoperative complications.

Major finding: Thirty-day mortality after bariatric surgery in immobile patients was 0.5%, vs. 0.1% for an ambulatory group (P less than .0001).

Data source: A comparison of 2015 MBSAQIP data for 145,741 ambulatory patients and 2,969 immobile patients before bariatric surgery.

Disclosures: Dr. Higgins had no relevant financial disclosures.

Think beyond BMI to optimize bariatric patients presurgery

NEW YORK – A structured, four-pronged approach to get patients as fit and healthy as possible prior to bariatric surgery holds the potential to improve postoperative outcomes. In general, bariatric surgery patients are in a better position than most surgery candidates because of a longer preoperative period. During this time, surgeons can work with a multidisciplinary team to optimize any medical, nutritional, exercise-related, and mental health concerns.

“People focus on the size of our patients and the weight of our patients, but [body mass index] is only one factor. They can have many other comorbidities that are significant,” Dr. LaMasters said. Patients can present with cardiac and pulmonary issues, hypertension, sleep apnea, diabetes, asthma, reflux and “a very high incidence of anxiety and depression.”

“So we have a lot of challenges,” she added. “We take care of complex, high-risk patients, and our goal is to improve outcomes. Using presurgery optimization can be a key to that.”

Maximizing medical readiness

Multiple providers drive the medical intervention, Dr. LaMasters said, including surgeons and primary care doctors, as well as advanced practice providers, medical weight loss providers, and other specialists. “We do try to get patients to lose weight before surgery, but that’s not an absolute requirement. More important is adjustment of other risk factors like pulmonary risk factors, control of hypertension, treatment of sleep apnea, and control of hyperglycemia. We’d like to have their A1c [test results to be] under 8%. We want to start [proton pump inhibitors] early because there is a very high prevalence of reflux and gastritis in this population.”

Bariatric surgery patients “are uniquely positioned to have a substantial benefit from that ‘prehabilitation,’ but this only works if you have a multidisciplinary team,” Dr. LaMasters said at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference. “Think of this as down-staging disease, like in a cancer model.”

“The message from this is there is an opportunity if we build it into the prehab phase of care. It’s a new way of thinking in surgery. You can change your results,” said session moderator David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS, Executive Director of the American College of Surgeons.

Nutritional know-how

Dietitians determine the second component – how to optimize nutrition before surgery. They focus on education, evaluation, setting goals, “and very importantly, supporting patients to attain those goals,” Dr. LaMasters said. Goals include increasing protein intake prior to surgery to a recommended 1.5 g/kg/day and starting nutritional supplements ahead of time.

Even though they typically consume an excess amount of calories, “many of our patients have baseline malnutrition,” Dr. LaMasters said. Establishing mindful behavior for meal planning, preparation, and eating is a potential solution, as is addressing any socioeconomic factors that can present challenges to healthy eating.

Emphasizing exercise

“The exercise piece is really key for our patients,” Dr. LaMasters said. Many candidates for bariatric surgery have mobility issues. “The first thing many say is ‘I can’t exercise.’ We instruct them that they can exercise. Our job is to find out what they can do – there are many different exercise modalities.”

A good baseline assessment is a 6-minute walk test to assess their distance limits, oxygen level, and any resulting symptoms.

“Our goal is to get them to walking – even those who can barely walk with a walker – for 5-10 minutes, six times a day,” Dr. LaMasters said. “We feel that is a minimum threshold to prevent blood clots after surgery.” Another recommendation is to get surgical candidates to do some activity 30 minutes a day, four times a week, at a minimum. “Eventually, after surgery and when they’ve lost weight and are healthier, the goal is going to be 1 hour, five days a week.”

Start the exercise program at least 4-8 weeks prior to surgery. Most studies show significant benefit if you start at least 4 weeks prior to surgery, Dr. LaMasters suggested. “In our own practice, we’ve seen if you can start a daily walking program even just 2 weeks prior to surgery, we see a significant benefit.”

Addressing anxiety or depression

The mental health piece is very important and should be guided by mental health providers on the multidisciplinary team, Dr. LaMasters said.

“Our patients have a high degree of stress in their lives, especially related to socioeconomic factors. A patient who does not have their anxiety or depression under control will not do as well after surgery.”

Optimization in other specialties

The benefits of a prehabilitation exercise program have been demonstrated across many other specialties, especially in colorectal surgery, cardiovascular surgery, and orthopedic surgery, Dr. LaMasters said. In randomized, controlled studies, this optimization is associated with decreased complications, mortality, and length of hospital stay.

“There is actually way less data from bariatric studies. I suggest to you that our bariatric surgery patients have similar comorbidities when compared with those other specialties – specialties that refer their patients to us for treatment,” Dr. LaMasters said.

In a study of cardiorespiratory fitness before bariatric surgery, other researchers found that the most serious postoperative complications occurred more often among patients who were less fit preoperatively (Chest. 2006 Aug;130[2]:517-25). These investigators measured peak oxygen consumption (VO2) preoperatively in 109 patients. “Each unit increase in peak VO2 rate was associated with 61% decrease in overall complications,” Dr. LaMasters said. “So a small increase in fitness led to a big decrease in complications.”

Other researchers compared optimization of exercise, nutrition, and psychological factors before and after surgery in 185 patients with colorectal cancer (Acta Oncol. 2017 Feb;56[2]:295-300). A control group received the interventions postoperatively. “They found a statistically significant difference in the prehabilitation group in increased functional capacity, with more than a 30-meter improvement in 6-minute walk test before surgery,” Dr. LaMasters said. Although the 6-minute walk test results decreased 4 weeks after surgery, as might be expected, by 8 weeks the prehabilitation patients performed better than controls – and even better than their own baseline, she added. “This model of optimization can be very well applied in bariatric surgery.”

“The goal is safe surgery with outstanding long-term outcomes,” Dr. LaMasters said. “It is really not enough in this era to ‘get a patient through surgery.’ We really need to optimize the risk factors we can and identify any areas where they will have additional needs after surgery,” she added. “This will allow us to have excellent outcomes in this complex patient population.”

Dr. LaMasters and Dr. Hoyt had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – A structured, four-pronged approach to get patients as fit and healthy as possible prior to bariatric surgery holds the potential to improve postoperative outcomes. In general, bariatric surgery patients are in a better position than most surgery candidates because of a longer preoperative period. During this time, surgeons can work with a multidisciplinary team to optimize any medical, nutritional, exercise-related, and mental health concerns.

“People focus on the size of our patients and the weight of our patients, but [body mass index] is only one factor. They can have many other comorbidities that are significant,” Dr. LaMasters said. Patients can present with cardiac and pulmonary issues, hypertension, sleep apnea, diabetes, asthma, reflux and “a very high incidence of anxiety and depression.”

“So we have a lot of challenges,” she added. “We take care of complex, high-risk patients, and our goal is to improve outcomes. Using presurgery optimization can be a key to that.”

Maximizing medical readiness

Multiple providers drive the medical intervention, Dr. LaMasters said, including surgeons and primary care doctors, as well as advanced practice providers, medical weight loss providers, and other specialists. “We do try to get patients to lose weight before surgery, but that’s not an absolute requirement. More important is adjustment of other risk factors like pulmonary risk factors, control of hypertension, treatment of sleep apnea, and control of hyperglycemia. We’d like to have their A1c [test results to be] under 8%. We want to start [proton pump inhibitors] early because there is a very high prevalence of reflux and gastritis in this population.”

Bariatric surgery patients “are uniquely positioned to have a substantial benefit from that ‘prehabilitation,’ but this only works if you have a multidisciplinary team,” Dr. LaMasters said at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference. “Think of this as down-staging disease, like in a cancer model.”

“The message from this is there is an opportunity if we build it into the prehab phase of care. It’s a new way of thinking in surgery. You can change your results,” said session moderator David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS, Executive Director of the American College of Surgeons.

Nutritional know-how

Dietitians determine the second component – how to optimize nutrition before surgery. They focus on education, evaluation, setting goals, “and very importantly, supporting patients to attain those goals,” Dr. LaMasters said. Goals include increasing protein intake prior to surgery to a recommended 1.5 g/kg/day and starting nutritional supplements ahead of time.

Even though they typically consume an excess amount of calories, “many of our patients have baseline malnutrition,” Dr. LaMasters said. Establishing mindful behavior for meal planning, preparation, and eating is a potential solution, as is addressing any socioeconomic factors that can present challenges to healthy eating.

Emphasizing exercise

“The exercise piece is really key for our patients,” Dr. LaMasters said. Many candidates for bariatric surgery have mobility issues. “The first thing many say is ‘I can’t exercise.’ We instruct them that they can exercise. Our job is to find out what they can do – there are many different exercise modalities.”

A good baseline assessment is a 6-minute walk test to assess their distance limits, oxygen level, and any resulting symptoms.

“Our goal is to get them to walking – even those who can barely walk with a walker – for 5-10 minutes, six times a day,” Dr. LaMasters said. “We feel that is a minimum threshold to prevent blood clots after surgery.” Another recommendation is to get surgical candidates to do some activity 30 minutes a day, four times a week, at a minimum. “Eventually, after surgery and when they’ve lost weight and are healthier, the goal is going to be 1 hour, five days a week.”

Start the exercise program at least 4-8 weeks prior to surgery. Most studies show significant benefit if you start at least 4 weeks prior to surgery, Dr. LaMasters suggested. “In our own practice, we’ve seen if you can start a daily walking program even just 2 weeks prior to surgery, we see a significant benefit.”

Addressing anxiety or depression

The mental health piece is very important and should be guided by mental health providers on the multidisciplinary team, Dr. LaMasters said.

“Our patients have a high degree of stress in their lives, especially related to socioeconomic factors. A patient who does not have their anxiety or depression under control will not do as well after surgery.”

Optimization in other specialties

The benefits of a prehabilitation exercise program have been demonstrated across many other specialties, especially in colorectal surgery, cardiovascular surgery, and orthopedic surgery, Dr. LaMasters said. In randomized, controlled studies, this optimization is associated with decreased complications, mortality, and length of hospital stay.

“There is actually way less data from bariatric studies. I suggest to you that our bariatric surgery patients have similar comorbidities when compared with those other specialties – specialties that refer their patients to us for treatment,” Dr. LaMasters said.

In a study of cardiorespiratory fitness before bariatric surgery, other researchers found that the most serious postoperative complications occurred more often among patients who were less fit preoperatively (Chest. 2006 Aug;130[2]:517-25). These investigators measured peak oxygen consumption (VO2) preoperatively in 109 patients. “Each unit increase in peak VO2 rate was associated with 61% decrease in overall complications,” Dr. LaMasters said. “So a small increase in fitness led to a big decrease in complications.”

Other researchers compared optimization of exercise, nutrition, and psychological factors before and after surgery in 185 patients with colorectal cancer (Acta Oncol. 2017 Feb;56[2]:295-300). A control group received the interventions postoperatively. “They found a statistically significant difference in the prehabilitation group in increased functional capacity, with more than a 30-meter improvement in 6-minute walk test before surgery,” Dr. LaMasters said. Although the 6-minute walk test results decreased 4 weeks after surgery, as might be expected, by 8 weeks the prehabilitation patients performed better than controls – and even better than their own baseline, she added. “This model of optimization can be very well applied in bariatric surgery.”

“The goal is safe surgery with outstanding long-term outcomes,” Dr. LaMasters said. “It is really not enough in this era to ‘get a patient through surgery.’ We really need to optimize the risk factors we can and identify any areas where they will have additional needs after surgery,” she added. “This will allow us to have excellent outcomes in this complex patient population.”

Dr. LaMasters and Dr. Hoyt had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – A structured, four-pronged approach to get patients as fit and healthy as possible prior to bariatric surgery holds the potential to improve postoperative outcomes. In general, bariatric surgery patients are in a better position than most surgery candidates because of a longer preoperative period. During this time, surgeons can work with a multidisciplinary team to optimize any medical, nutritional, exercise-related, and mental health concerns.

“People focus on the size of our patients and the weight of our patients, but [body mass index] is only one factor. They can have many other comorbidities that are significant,” Dr. LaMasters said. Patients can present with cardiac and pulmonary issues, hypertension, sleep apnea, diabetes, asthma, reflux and “a very high incidence of anxiety and depression.”

“So we have a lot of challenges,” she added. “We take care of complex, high-risk patients, and our goal is to improve outcomes. Using presurgery optimization can be a key to that.”

Maximizing medical readiness

Multiple providers drive the medical intervention, Dr. LaMasters said, including surgeons and primary care doctors, as well as advanced practice providers, medical weight loss providers, and other specialists. “We do try to get patients to lose weight before surgery, but that’s not an absolute requirement. More important is adjustment of other risk factors like pulmonary risk factors, control of hypertension, treatment of sleep apnea, and control of hyperglycemia. We’d like to have their A1c [test results to be] under 8%. We want to start [proton pump inhibitors] early because there is a very high prevalence of reflux and gastritis in this population.”

Bariatric surgery patients “are uniquely positioned to have a substantial benefit from that ‘prehabilitation,’ but this only works if you have a multidisciplinary team,” Dr. LaMasters said at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference. “Think of this as down-staging disease, like in a cancer model.”

“The message from this is there is an opportunity if we build it into the prehab phase of care. It’s a new way of thinking in surgery. You can change your results,” said session moderator David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS, Executive Director of the American College of Surgeons.

Nutritional know-how

Dietitians determine the second component – how to optimize nutrition before surgery. They focus on education, evaluation, setting goals, “and very importantly, supporting patients to attain those goals,” Dr. LaMasters said. Goals include increasing protein intake prior to surgery to a recommended 1.5 g/kg/day and starting nutritional supplements ahead of time.

Even though they typically consume an excess amount of calories, “many of our patients have baseline malnutrition,” Dr. LaMasters said. Establishing mindful behavior for meal planning, preparation, and eating is a potential solution, as is addressing any socioeconomic factors that can present challenges to healthy eating.

Emphasizing exercise

“The exercise piece is really key for our patients,” Dr. LaMasters said. Many candidates for bariatric surgery have mobility issues. “The first thing many say is ‘I can’t exercise.’ We instruct them that they can exercise. Our job is to find out what they can do – there are many different exercise modalities.”

A good baseline assessment is a 6-minute walk test to assess their distance limits, oxygen level, and any resulting symptoms.

“Our goal is to get them to walking – even those who can barely walk with a walker – for 5-10 minutes, six times a day,” Dr. LaMasters said. “We feel that is a minimum threshold to prevent blood clots after surgery.” Another recommendation is to get surgical candidates to do some activity 30 minutes a day, four times a week, at a minimum. “Eventually, after surgery and when they’ve lost weight and are healthier, the goal is going to be 1 hour, five days a week.”

Start the exercise program at least 4-8 weeks prior to surgery. Most studies show significant benefit if you start at least 4 weeks prior to surgery, Dr. LaMasters suggested. “In our own practice, we’ve seen if you can start a daily walking program even just 2 weeks prior to surgery, we see a significant benefit.”

Addressing anxiety or depression

The mental health piece is very important and should be guided by mental health providers on the multidisciplinary team, Dr. LaMasters said.

“Our patients have a high degree of stress in their lives, especially related to socioeconomic factors. A patient who does not have their anxiety or depression under control will not do as well after surgery.”

Optimization in other specialties

The benefits of a prehabilitation exercise program have been demonstrated across many other specialties, especially in colorectal surgery, cardiovascular surgery, and orthopedic surgery, Dr. LaMasters said. In randomized, controlled studies, this optimization is associated with decreased complications, mortality, and length of hospital stay.

“There is actually way less data from bariatric studies. I suggest to you that our bariatric surgery patients have similar comorbidities when compared with those other specialties – specialties that refer their patients to us for treatment,” Dr. LaMasters said.

In a study of cardiorespiratory fitness before bariatric surgery, other researchers found that the most serious postoperative complications occurred more often among patients who were less fit preoperatively (Chest. 2006 Aug;130[2]:517-25). These investigators measured peak oxygen consumption (VO2) preoperatively in 109 patients. “Each unit increase in peak VO2 rate was associated with 61% decrease in overall complications,” Dr. LaMasters said. “So a small increase in fitness led to a big decrease in complications.”

Other researchers compared optimization of exercise, nutrition, and psychological factors before and after surgery in 185 patients with colorectal cancer (Acta Oncol. 2017 Feb;56[2]:295-300). A control group received the interventions postoperatively. “They found a statistically significant difference in the prehabilitation group in increased functional capacity, with more than a 30-meter improvement in 6-minute walk test before surgery,” Dr. LaMasters said. Although the 6-minute walk test results decreased 4 weeks after surgery, as might be expected, by 8 weeks the prehabilitation patients performed better than controls – and even better than their own baseline, she added. “This model of optimization can be very well applied in bariatric surgery.”

“The goal is safe surgery with outstanding long-term outcomes,” Dr. LaMasters said. “It is really not enough in this era to ‘get a patient through surgery.’ We really need to optimize the risk factors we can and identify any areas where they will have additional needs after surgery,” she added. “This will allow us to have excellent outcomes in this complex patient population.”

Dr. LaMasters and Dr. Hoyt had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ACS QUALITY & SAFETY CONFERENCE

MBSAQIP data helped target problem areas to cut readmissions

NEW YORK – Targeted interventions aimed at reducing patient readmission after bariatric surgery at a high-volume academic medical center led to a 61% overall decrease year over year. The center also saw a substantial reduction in readmissions linked to the top three factors of readmission identified by the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program, as well as a precipitous drop in the revisional surgery readmission rate.

“Our center, like so many others, has quarterly meetings in accordance with the MBSAQIP to look at our data. And this led to recognition of some common reasons for readmission,” said Chetan V. Aher, MD, a general surgeon at the department of surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn. Oral (PO) intolerance, dehydration, and nonemergent abdominal pain were the top reasons flagged by the MBSAQIP registry data at the medical center. Dr. Aher and his colleagues moved to focus on postoperative diet, administration of medications, management of patients who return to the hospital after surgery, and optimal staffing.

“Notably, the readmission rate for revisional procedures decreased by a whopping 90%,” Dr. Aher said. “I think a lot of these targeted interventions just really helped these patients who were at a higher risk to begin with to be readmitted.”

New dietary dos and don’ts

“We changed our postoperative diet,” Dr. Aher said. Instead of a soft food diet a couple of days after surgery, the full liquid diet was extended to 3 weeks post surgery.

The clinicians also implemented what they called a ‘no MEALS’ policy, which stands for no Meat, Eggs And Leftovers. “We were having problems with meat, although tender fish was okay, and some other things that went down easily,” Dr. Aher said at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference. “We had some complaints about no eggs after surgery. A lot of patients love eggs,” he added. But they recommended avoiding eggs for 1 month after bariatric surgery to avoid nausea.

“Avoiding leftovers was also a big deal for patients,” Dr. Aher said. But patients who microwaved leftovers would “then come into the hospital with problems.”

Medication modifications

Another frequent cause of nausea was a “terrible and off-putting” taste when crushed tablets or medication capsules were added to the patient’s diet. Changing how patients took their medication “was a big help.” At the same time, there was a large institutional effort at Vanderbilt to start providing discharge medications in the hospital to increase postoperative compliance. “Bariatric surgery was one of the pilot programs for this,” Dr. Aher said. Discharge medications were filled by the pharmacy at Vanderbilt and delivered to the patient’s room, and a pharmacist or pharmacy intern explained how to use them. Compliance on medications increased, which may in turn have had an impact on readmissions.

Changes to patient management

Dr. Aher and his colleagues also changed where they treated patients who returned with problems. “Previously, when patients called in, the clinic diverted them to the emergency room. We stopped doing that, and increased our capacity to see these patients in the clinic instead.” This led to an increase in use of IV hydration in the clinic.

A meeting attendee asked if providing this service led to any problems with clinic capacity.

“Sometimes,” Dr. Aher said. “We don’t have a huge number of patients coming in for IV hydration, but when we had two come in on the same day, it did take up a couple of exam rooms.” To address this, the clinicians found other space in the clinic that would offer privacy for patients while not tying up exam rooms.

In addition, the clinic expanded nurse practitioner availability to 5 days a week to make the discharge process more consistent. “Of course, as we rolled all these things out, we made sure our educational material was updated accordingly,” Dr. Aher said.

The study demonstrates that a collaborative team effort and targeted interventions can result in a significant reduction in readmissions, Dr. Aher said. “Regular quality focused meetings are really important to facilitate recognition of various areas for improvement, especially in a high-volume center. Introducing an MBSAQIP registry serves as an excellent tool to effect these changes,” he said.

Dr. Aher had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – Targeted interventions aimed at reducing patient readmission after bariatric surgery at a high-volume academic medical center led to a 61% overall decrease year over year. The center also saw a substantial reduction in readmissions linked to the top three factors of readmission identified by the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program, as well as a precipitous drop in the revisional surgery readmission rate.

“Our center, like so many others, has quarterly meetings in accordance with the MBSAQIP to look at our data. And this led to recognition of some common reasons for readmission,” said Chetan V. Aher, MD, a general surgeon at the department of surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn. Oral (PO) intolerance, dehydration, and nonemergent abdominal pain were the top reasons flagged by the MBSAQIP registry data at the medical center. Dr. Aher and his colleagues moved to focus on postoperative diet, administration of medications, management of patients who return to the hospital after surgery, and optimal staffing.

“Notably, the readmission rate for revisional procedures decreased by a whopping 90%,” Dr. Aher said. “I think a lot of these targeted interventions just really helped these patients who were at a higher risk to begin with to be readmitted.”

New dietary dos and don’ts

“We changed our postoperative diet,” Dr. Aher said. Instead of a soft food diet a couple of days after surgery, the full liquid diet was extended to 3 weeks post surgery.

The clinicians also implemented what they called a ‘no MEALS’ policy, which stands for no Meat, Eggs And Leftovers. “We were having problems with meat, although tender fish was okay, and some other things that went down easily,” Dr. Aher said at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference. “We had some complaints about no eggs after surgery. A lot of patients love eggs,” he added. But they recommended avoiding eggs for 1 month after bariatric surgery to avoid nausea.

“Avoiding leftovers was also a big deal for patients,” Dr. Aher said. But patients who microwaved leftovers would “then come into the hospital with problems.”

Medication modifications

Another frequent cause of nausea was a “terrible and off-putting” taste when crushed tablets or medication capsules were added to the patient’s diet. Changing how patients took their medication “was a big help.” At the same time, there was a large institutional effort at Vanderbilt to start providing discharge medications in the hospital to increase postoperative compliance. “Bariatric surgery was one of the pilot programs for this,” Dr. Aher said. Discharge medications were filled by the pharmacy at Vanderbilt and delivered to the patient’s room, and a pharmacist or pharmacy intern explained how to use them. Compliance on medications increased, which may in turn have had an impact on readmissions.

Changes to patient management

Dr. Aher and his colleagues also changed where they treated patients who returned with problems. “Previously, when patients called in, the clinic diverted them to the emergency room. We stopped doing that, and increased our capacity to see these patients in the clinic instead.” This led to an increase in use of IV hydration in the clinic.

A meeting attendee asked if providing this service led to any problems with clinic capacity.

“Sometimes,” Dr. Aher said. “We don’t have a huge number of patients coming in for IV hydration, but when we had two come in on the same day, it did take up a couple of exam rooms.” To address this, the clinicians found other space in the clinic that would offer privacy for patients while not tying up exam rooms.

In addition, the clinic expanded nurse practitioner availability to 5 days a week to make the discharge process more consistent. “Of course, as we rolled all these things out, we made sure our educational material was updated accordingly,” Dr. Aher said.

The study demonstrates that a collaborative team effort and targeted interventions can result in a significant reduction in readmissions, Dr. Aher said. “Regular quality focused meetings are really important to facilitate recognition of various areas for improvement, especially in a high-volume center. Introducing an MBSAQIP registry serves as an excellent tool to effect these changes,” he said.

Dr. Aher had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – Targeted interventions aimed at reducing patient readmission after bariatric surgery at a high-volume academic medical center led to a 61% overall decrease year over year. The center also saw a substantial reduction in readmissions linked to the top three factors of readmission identified by the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program, as well as a precipitous drop in the revisional surgery readmission rate.

“Our center, like so many others, has quarterly meetings in accordance with the MBSAQIP to look at our data. And this led to recognition of some common reasons for readmission,” said Chetan V. Aher, MD, a general surgeon at the department of surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn. Oral (PO) intolerance, dehydration, and nonemergent abdominal pain were the top reasons flagged by the MBSAQIP registry data at the medical center. Dr. Aher and his colleagues moved to focus on postoperative diet, administration of medications, management of patients who return to the hospital after surgery, and optimal staffing.

“Notably, the readmission rate for revisional procedures decreased by a whopping 90%,” Dr. Aher said. “I think a lot of these targeted interventions just really helped these patients who were at a higher risk to begin with to be readmitted.”

New dietary dos and don’ts

“We changed our postoperative diet,” Dr. Aher said. Instead of a soft food diet a couple of days after surgery, the full liquid diet was extended to 3 weeks post surgery.

The clinicians also implemented what they called a ‘no MEALS’ policy, which stands for no Meat, Eggs And Leftovers. “We were having problems with meat, although tender fish was okay, and some other things that went down easily,” Dr. Aher said at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference. “We had some complaints about no eggs after surgery. A lot of patients love eggs,” he added. But they recommended avoiding eggs for 1 month after bariatric surgery to avoid nausea.

“Avoiding leftovers was also a big deal for patients,” Dr. Aher said. But patients who microwaved leftovers would “then come into the hospital with problems.”

Medication modifications

Another frequent cause of nausea was a “terrible and off-putting” taste when crushed tablets or medication capsules were added to the patient’s diet. Changing how patients took their medication “was a big help.” At the same time, there was a large institutional effort at Vanderbilt to start providing discharge medications in the hospital to increase postoperative compliance. “Bariatric surgery was one of the pilot programs for this,” Dr. Aher said. Discharge medications were filled by the pharmacy at Vanderbilt and delivered to the patient’s room, and a pharmacist or pharmacy intern explained how to use them. Compliance on medications increased, which may in turn have had an impact on readmissions.

Changes to patient management

Dr. Aher and his colleagues also changed where they treated patients who returned with problems. “Previously, when patients called in, the clinic diverted them to the emergency room. We stopped doing that, and increased our capacity to see these patients in the clinic instead.” This led to an increase in use of IV hydration in the clinic.

A meeting attendee asked if providing this service led to any problems with clinic capacity.

“Sometimes,” Dr. Aher said. “We don’t have a huge number of patients coming in for IV hydration, but when we had two come in on the same day, it did take up a couple of exam rooms.” To address this, the clinicians found other space in the clinic that would offer privacy for patients while not tying up exam rooms.

In addition, the clinic expanded nurse practitioner availability to 5 days a week to make the discharge process more consistent. “Of course, as we rolled all these things out, we made sure our educational material was updated accordingly,” Dr. Aher said.

The study demonstrates that a collaborative team effort and targeted interventions can result in a significant reduction in readmissions, Dr. Aher said. “Regular quality focused meetings are really important to facilitate recognition of various areas for improvement, especially in a high-volume center. Introducing an MBSAQIP registry serves as an excellent tool to effect these changes,” he said.

Dr. Aher had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ACS QUALITY & SAFETY CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: A collaborative effort and target interventions can successfully reduce bariatric surgery readmissions.

Major finding: The overall bariatric surgery readmission rate dropped 61% in the year after intervention compared to the previous year.

Data source: Comparison of 471 bariatric procedures in 2015 to 539 others in 2016 at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Disclosures: Dr. Aher had no relevant financial disclosures.

ERAS program cuts complications after radical cystectomy

NEW YORK – Prior to October 2014, urology patients undergoing radical cystectomy at a 950-bed, tertiary care hospital experienced postoperative morbidity at a relative high rate, according to NSQIP data.

“Despite improvements in surgical techniques and perioperative care protocols, the rate of the overall morbidity for radical cystectomy was higher than we would like to see,” said Tracey Hong, RN, BScN, of the Clinical Quality and Patient Safety Department at Vancouver (B.C.) General Hospital. “We took this as an opportunity to improve our patient outcomes and experience.”

Vancouver General joined the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Improvement Quality Program (ACS NSQIP) in 2011. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) perioperative protocol the institution adopted in late 2014 was associated with a 32% decrease in overall morbidity. The rate dropped from 31.3% in the pre-ERAS study period from May 2011 to September 2014, to 21.1% after implementation, from October 2014 to September 2016, according to a study Ms. Hong presented at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference.

The investigators compared outcomes between all 92 people undergoing elective radical cystectomy during the first time period to 152 consecutive patients treated under the ERAS protocol. Median length of stay decreased from 8 days before ERAS to 7 days after, a significant difference (P less than .05).

The researchers also assessed outcomes based on how adherent clinicians were to 12 key elements of the 26-item ERAS initiative. These elements included preoperative counseling, preoperative anesthesia consultation, and carbohydrate loading on the morning of surgery. Intraoperatively, they tracked normothermia, use of multimodal anesthesia, use of goal-directed fluid therapy using a monitor, timely antibiotics, and adequate postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis. The four postoperative key measures were mobilization at least once by postoperative day 0, full fluids and mobilization twice on postoperative day 1, and starting solid food by postoperative day 4.

A total 52% of the ERAS cases were associated with 75% or greater adherence to these 12 key items. Adherence with the intraoperative fluid therapy and all the postoperative elements proved to be the most challenging, Ms. Hong said.

The more adherent cases experienced a lower overall postoperative morbidity rate, 15.2%, compared with 27.4% among the less adherent group. The 15.2% morbidity among the more adherent cases also compared favorably with the 31.1% rate for cases prior to ERAS adoption.

“We will continue working on improving compliance,” Ms. Hong said. “We need to increase adherence to goal-directed fluid therapy and the postoperative components,” Ms. Hong said.

Three main strategies remain essential to the ongoing success of the ERAS program, Ms. Hong said. Empowering patients to be active participants and to engage in their own health outcomes is one. “Second, we involve a multidisciplinary team at an early stage so they take ownership and get engaged in the program,” she said. “Last but not least, we continue to measure the outcomes in 100% of cases.”

Continuous auditing and sharing results with the team on a regular basis will be necessary to maintain engagement in the ERAS protocol going forward, Ms. Hong added. “Tenacity is vital.”

Ms. Hong had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – Prior to October 2014, urology patients undergoing radical cystectomy at a 950-bed, tertiary care hospital experienced postoperative morbidity at a relative high rate, according to NSQIP data.

“Despite improvements in surgical techniques and perioperative care protocols, the rate of the overall morbidity for radical cystectomy was higher than we would like to see,” said Tracey Hong, RN, BScN, of the Clinical Quality and Patient Safety Department at Vancouver (B.C.) General Hospital. “We took this as an opportunity to improve our patient outcomes and experience.”

Vancouver General joined the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Improvement Quality Program (ACS NSQIP) in 2011. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) perioperative protocol the institution adopted in late 2014 was associated with a 32% decrease in overall morbidity. The rate dropped from 31.3% in the pre-ERAS study period from May 2011 to September 2014, to 21.1% after implementation, from October 2014 to September 2016, according to a study Ms. Hong presented at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference.

The investigators compared outcomes between all 92 people undergoing elective radical cystectomy during the first time period to 152 consecutive patients treated under the ERAS protocol. Median length of stay decreased from 8 days before ERAS to 7 days after, a significant difference (P less than .05).

The researchers also assessed outcomes based on how adherent clinicians were to 12 key elements of the 26-item ERAS initiative. These elements included preoperative counseling, preoperative anesthesia consultation, and carbohydrate loading on the morning of surgery. Intraoperatively, they tracked normothermia, use of multimodal anesthesia, use of goal-directed fluid therapy using a monitor, timely antibiotics, and adequate postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis. The four postoperative key measures were mobilization at least once by postoperative day 0, full fluids and mobilization twice on postoperative day 1, and starting solid food by postoperative day 4.

A total 52% of the ERAS cases were associated with 75% or greater adherence to these 12 key items. Adherence with the intraoperative fluid therapy and all the postoperative elements proved to be the most challenging, Ms. Hong said.

The more adherent cases experienced a lower overall postoperative morbidity rate, 15.2%, compared with 27.4% among the less adherent group. The 15.2% morbidity among the more adherent cases also compared favorably with the 31.1% rate for cases prior to ERAS adoption.

“We will continue working on improving compliance,” Ms. Hong said. “We need to increase adherence to goal-directed fluid therapy and the postoperative components,” Ms. Hong said.

Three main strategies remain essential to the ongoing success of the ERAS program, Ms. Hong said. Empowering patients to be active participants and to engage in their own health outcomes is one. “Second, we involve a multidisciplinary team at an early stage so they take ownership and get engaged in the program,” she said. “Last but not least, we continue to measure the outcomes in 100% of cases.”

Continuous auditing and sharing results with the team on a regular basis will be necessary to maintain engagement in the ERAS protocol going forward, Ms. Hong added. “Tenacity is vital.”

Ms. Hong had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – Prior to October 2014, urology patients undergoing radical cystectomy at a 950-bed, tertiary care hospital experienced postoperative morbidity at a relative high rate, according to NSQIP data.

“Despite improvements in surgical techniques and perioperative care protocols, the rate of the overall morbidity for radical cystectomy was higher than we would like to see,” said Tracey Hong, RN, BScN, of the Clinical Quality and Patient Safety Department at Vancouver (B.C.) General Hospital. “We took this as an opportunity to improve our patient outcomes and experience.”

Vancouver General joined the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Improvement Quality Program (ACS NSQIP) in 2011. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) perioperative protocol the institution adopted in late 2014 was associated with a 32% decrease in overall morbidity. The rate dropped from 31.3% in the pre-ERAS study period from May 2011 to September 2014, to 21.1% after implementation, from October 2014 to September 2016, according to a study Ms. Hong presented at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference.

The investigators compared outcomes between all 92 people undergoing elective radical cystectomy during the first time period to 152 consecutive patients treated under the ERAS protocol. Median length of stay decreased from 8 days before ERAS to 7 days after, a significant difference (P less than .05).

The researchers also assessed outcomes based on how adherent clinicians were to 12 key elements of the 26-item ERAS initiative. These elements included preoperative counseling, preoperative anesthesia consultation, and carbohydrate loading on the morning of surgery. Intraoperatively, they tracked normothermia, use of multimodal anesthesia, use of goal-directed fluid therapy using a monitor, timely antibiotics, and adequate postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis. The four postoperative key measures were mobilization at least once by postoperative day 0, full fluids and mobilization twice on postoperative day 1, and starting solid food by postoperative day 4.

A total 52% of the ERAS cases were associated with 75% or greater adherence to these 12 key items. Adherence with the intraoperative fluid therapy and all the postoperative elements proved to be the most challenging, Ms. Hong said.

The more adherent cases experienced a lower overall postoperative morbidity rate, 15.2%, compared with 27.4% among the less adherent group. The 15.2% morbidity among the more adherent cases also compared favorably with the 31.1% rate for cases prior to ERAS adoption.

“We will continue working on improving compliance,” Ms. Hong said. “We need to increase adherence to goal-directed fluid therapy and the postoperative components,” Ms. Hong said.

Three main strategies remain essential to the ongoing success of the ERAS program, Ms. Hong said. Empowering patients to be active participants and to engage in their own health outcomes is one. “Second, we involve a multidisciplinary team at an early stage so they take ownership and get engaged in the program,” she said. “Last but not least, we continue to measure the outcomes in 100% of cases.”

Continuous auditing and sharing results with the team on a regular basis will be necessary to maintain engagement in the ERAS protocol going forward, Ms. Hong added. “Tenacity is vital.”

Ms. Hong had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ACS QUALITY & SAFETY CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: An enhanced recovery after surgery protocol can reduce postoperative morbidity after radical cystectomy.

Major finding: Investigators report a 32% decrease in overall morbidity after adoption of ERAS pathways.

Data source: Comparison between 92 patients before and 152 patients after implementation of ERAS protocol.

Disclosures: Tracey Hong, BScN, had no relevant financial disclosures.

Fluid protocol takes aim at bariatric surgery readmissions

NEW YORK – With dehydration considered a contributor to hospital readmission after bariatric weight loss surgery, a multidisciplinary team of clinicians searched for a way to get patients to drink up. Specifically,

The project results were presented at a poster session at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference.

“Our QI project was to streamline that process to ultimately eliminate or decrease those readmits,” Ms. Melei said.

They used 8-ounce water bottles. To track water consumption, they also numbered the bottles one through six for each patient. One-ounce cups were used during mealtimes. RNs, certified nursing assistants, and food service staff were educated about the fluid intake initiative. Only fluids provided by nursing were permitted and patients also received a clear message about fluid goals.

Another focus was standardizing communication with patients. They were not getting a consistent message from staff on what to expect before, during, and after surgery. “So we had to make sure [we] were all saying the same thing.”

The nurses and the other staff now ask the patients “Did you finish the bottle?” or “Where are you with the bottles?” Ms. Melei said. “At the end of a shift, the nurses document fluid consumption.”