User login

Universal adolescent anxiety screening is feasible in primary care

BALTIMORE – according to a new study.

The findings suggest that implementing a universal anxiety screening for teen patients is feasible and improves detection of patients with anxiety.

“Our providers were able to act on these positive screens and are able to catch a really serious entry-level condition that may have otherwise been missed,” presenter Sarah Malik, MD, a resident at Penn State Children’s Hospital, told attendees at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. “Hopefully, this will make a really meaningful difference in these kids’ lives, which is, of course, what we all want.”

An estimated 32% of U.S. teens have anxiety, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, and “8.3% of adolescents with anxiety have severe impairment defined by DSM4 criteria,” according to the study’s background information. Yet neither the American Academy of Pediatrics nor the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has issued recommendations regarding screening for anxiety in teens.

“For this reason, we developed a study in which we implemented and measured the effect of a universal anxiety screening program in the pediatric primary care setting,” Dr Malik said.

The screening intervention took place in a single Penn State Health Children’s Hospital primary care practice in Hershey, Pa., that typically received 37,000 visits a year from 12,500 patients. The practice has 19 attending physicians, 4 nurse practitioners, and 21 residents.

Providers asked patients aged 11-18 years to fill out a nine-question Generalized Anxiety Disorder subscale of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) during their well-child visits from April 2017 to March 2018. Two-thirds of the patients had private insurance, 80% were white and 8% were black; 10% were Hispanic.

Providers had access to the screening results after nurses transcribed them into electronic medical records. The researchers used EMRs to determine how many patients completed a SCARED at their well-child visit and how many screened positive for anxiety, defined as a score of at least 9/18.

Then the providers compared the prevalence of anxiety 1 year after implementing the routine screening with the prevalence of teens with an ICD-10 anxiety diagnosis within the 36 months before the screening was implemented. The practice’s prevalence of adolescent anxiety was 13.3% 1 year after implementing universal anxiety screening, compared with 9.6% in the previous 3 years (P less than .0001).

Among 2,276 well-child visits for adolescents during the study period, 80% completed a SCARED. Of those who completed the screening, 17% screened positive. The physicians identified 70% of those patients with positive screens (214/306) as having anxiety, and 82% of those patients (n = 176) were diagnosed with anxiety.

About half of those diagnosed with anxiety (n = 93) received one or more interventions: 77 received referrals for counseling, 15 received psychiatric referrals, and 20 were prescribed new anxiety medication.

“We did find that a universal screening program for anxiety is very useful to implement in the primary care setting, and it’s also really effective at identifying adolescents with anxiety symptoms,” Dr. Malik said.

The study’s generalizability is limited by its implementation at a single academic center with integrated behavioral health, and the use of the SCARED, a portion of the GAD scale, is not considered a standard of care.

The researchers used no external funding, and they had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – according to a new study.

The findings suggest that implementing a universal anxiety screening for teen patients is feasible and improves detection of patients with anxiety.

“Our providers were able to act on these positive screens and are able to catch a really serious entry-level condition that may have otherwise been missed,” presenter Sarah Malik, MD, a resident at Penn State Children’s Hospital, told attendees at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. “Hopefully, this will make a really meaningful difference in these kids’ lives, which is, of course, what we all want.”

An estimated 32% of U.S. teens have anxiety, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, and “8.3% of adolescents with anxiety have severe impairment defined by DSM4 criteria,” according to the study’s background information. Yet neither the American Academy of Pediatrics nor the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has issued recommendations regarding screening for anxiety in teens.

“For this reason, we developed a study in which we implemented and measured the effect of a universal anxiety screening program in the pediatric primary care setting,” Dr Malik said.

The screening intervention took place in a single Penn State Health Children’s Hospital primary care practice in Hershey, Pa., that typically received 37,000 visits a year from 12,500 patients. The practice has 19 attending physicians, 4 nurse practitioners, and 21 residents.

Providers asked patients aged 11-18 years to fill out a nine-question Generalized Anxiety Disorder subscale of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) during their well-child visits from April 2017 to March 2018. Two-thirds of the patients had private insurance, 80% were white and 8% were black; 10% were Hispanic.

Providers had access to the screening results after nurses transcribed them into electronic medical records. The researchers used EMRs to determine how many patients completed a SCARED at their well-child visit and how many screened positive for anxiety, defined as a score of at least 9/18.

Then the providers compared the prevalence of anxiety 1 year after implementing the routine screening with the prevalence of teens with an ICD-10 anxiety diagnosis within the 36 months before the screening was implemented. The practice’s prevalence of adolescent anxiety was 13.3% 1 year after implementing universal anxiety screening, compared with 9.6% in the previous 3 years (P less than .0001).

Among 2,276 well-child visits for adolescents during the study period, 80% completed a SCARED. Of those who completed the screening, 17% screened positive. The physicians identified 70% of those patients with positive screens (214/306) as having anxiety, and 82% of those patients (n = 176) were diagnosed with anxiety.

About half of those diagnosed with anxiety (n = 93) received one or more interventions: 77 received referrals for counseling, 15 received psychiatric referrals, and 20 were prescribed new anxiety medication.

“We did find that a universal screening program for anxiety is very useful to implement in the primary care setting, and it’s also really effective at identifying adolescents with anxiety symptoms,” Dr. Malik said.

The study’s generalizability is limited by its implementation at a single academic center with integrated behavioral health, and the use of the SCARED, a portion of the GAD scale, is not considered a standard of care.

The researchers used no external funding, and they had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – according to a new study.

The findings suggest that implementing a universal anxiety screening for teen patients is feasible and improves detection of patients with anxiety.

“Our providers were able to act on these positive screens and are able to catch a really serious entry-level condition that may have otherwise been missed,” presenter Sarah Malik, MD, a resident at Penn State Children’s Hospital, told attendees at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. “Hopefully, this will make a really meaningful difference in these kids’ lives, which is, of course, what we all want.”

An estimated 32% of U.S. teens have anxiety, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, and “8.3% of adolescents with anxiety have severe impairment defined by DSM4 criteria,” according to the study’s background information. Yet neither the American Academy of Pediatrics nor the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has issued recommendations regarding screening for anxiety in teens.

“For this reason, we developed a study in which we implemented and measured the effect of a universal anxiety screening program in the pediatric primary care setting,” Dr Malik said.

The screening intervention took place in a single Penn State Health Children’s Hospital primary care practice in Hershey, Pa., that typically received 37,000 visits a year from 12,500 patients. The practice has 19 attending physicians, 4 nurse practitioners, and 21 residents.

Providers asked patients aged 11-18 years to fill out a nine-question Generalized Anxiety Disorder subscale of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) during their well-child visits from April 2017 to March 2018. Two-thirds of the patients had private insurance, 80% were white and 8% were black; 10% were Hispanic.

Providers had access to the screening results after nurses transcribed them into electronic medical records. The researchers used EMRs to determine how many patients completed a SCARED at their well-child visit and how many screened positive for anxiety, defined as a score of at least 9/18.

Then the providers compared the prevalence of anxiety 1 year after implementing the routine screening with the prevalence of teens with an ICD-10 anxiety diagnosis within the 36 months before the screening was implemented. The practice’s prevalence of adolescent anxiety was 13.3% 1 year after implementing universal anxiety screening, compared with 9.6% in the previous 3 years (P less than .0001).

Among 2,276 well-child visits for adolescents during the study period, 80% completed a SCARED. Of those who completed the screening, 17% screened positive. The physicians identified 70% of those patients with positive screens (214/306) as having anxiety, and 82% of those patients (n = 176) were diagnosed with anxiety.

About half of those diagnosed with anxiety (n = 93) received one or more interventions: 77 received referrals for counseling, 15 received psychiatric referrals, and 20 were prescribed new anxiety medication.

“We did find that a universal screening program for anxiety is very useful to implement in the primary care setting, and it’s also really effective at identifying adolescents with anxiety symptoms,” Dr. Malik said.

The study’s generalizability is limited by its implementation at a single academic center with integrated behavioral health, and the use of the SCARED, a portion of the GAD scale, is not considered a standard of care.

The researchers used no external funding, and they had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Key clinical point: Universal anxiety screening for adolescents is feasible and effective in pediatric primary care.

Major finding: Adolescent anxiety diagnoses increased from 9.6% to 13.3% 1 year after university screening (P less than .0001).

Study details: The findings are based on assessment of a universal anxiety screening program implemented at a single academic pediatric primary care practice, involving 2,276 well visits between April 2017 and March 2018 for patients aged 11-18 years.

Disclosures: The researchers used no external funding, and they had no disclosures.

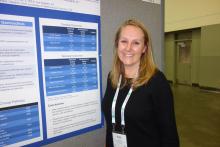

A gentler approach to gastroschisis improves outcomes

BALTIMORE – a condition in which infants are born with their intestines and sometimes other organs protruding through a hole beside the umbilicus.

Neonatologists, maternal-fetal health experts, and pediatric surgeons standardized a literature-based approach that was gentler and less invasive than usual management, emphasizing sutureless closure, sometimes at bedside on the first day of life, and early feeding. Often, it turned out, that’s all that children require.

It’s made a big difference. “We reduced the number of trips to the operating room and exposure to general anesthesia. We reduced the number of babies intubated and days on the ventilator. We reduced opioid days and antibiotic days” without increasing bacteremia, and “there are probably long-term benefits beyond the NICU,” said Kara Calkins, MD, at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

I think this is definitely ahead of the curve for NICUs. My hope is that the vast majority of universities adopt a similar approach,” said Dr. Calkins, who is an assistant professor of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“When I was a fellow,” she explained, “we took all of these babies and intubated them right away and put them on a drip to paralyze and sedate them. We put their bowels into a silo,” essentially a plastic bag suspended by a string, in the hopes that gravity would pull the bowels back into the abdomen. More often than not, however, “the surgeon would come by every day and slowly push them” back in over a week or so. “The fear was if you did it too quickly, you’d invoke an abdominal compartment syndrome, or respiratory decompensation. You had a baby intubated for a week, sedated and paralyzed.”

Infants were kept on total parenteral nutrition for weeks, sometimes through a Broviac central catheter.

It was overkill, Dr. Calkins said, when only the intestines are out and the abdominal wall defect isn’t too large or too small, which is the case for many infants.

For those children, sutureless closure over 1-3 days is the new goal. The bowel is worked back into the abdomen and the umbilical cord is pulled to the side to approximate the edges of the wound, and tacked down; the defect then heals itself. Antibiotics are discontinued 48 hours after closure. Gastric and rectal decompression helps with reduction.

Also, “we give drops of breast milk in their cheek right away, every couple of hours starting on the first day of life. Once the output from the gastric tube is clear, we start feeds. We still give total parenteral nutrition, but through a [peripherally inserted central catheter] in the arm,” Dr. Calkins said. “Use of breast milk for this population is important” to help establish a healthy microbiome, among other reasons.

Another improvement that had been made, according to Dr. Calkins, is that if only the intestines are out, women carry their baby to term and deliver vaginally. The old practice was to deliver babies preterm by Cesarean section, she explained.

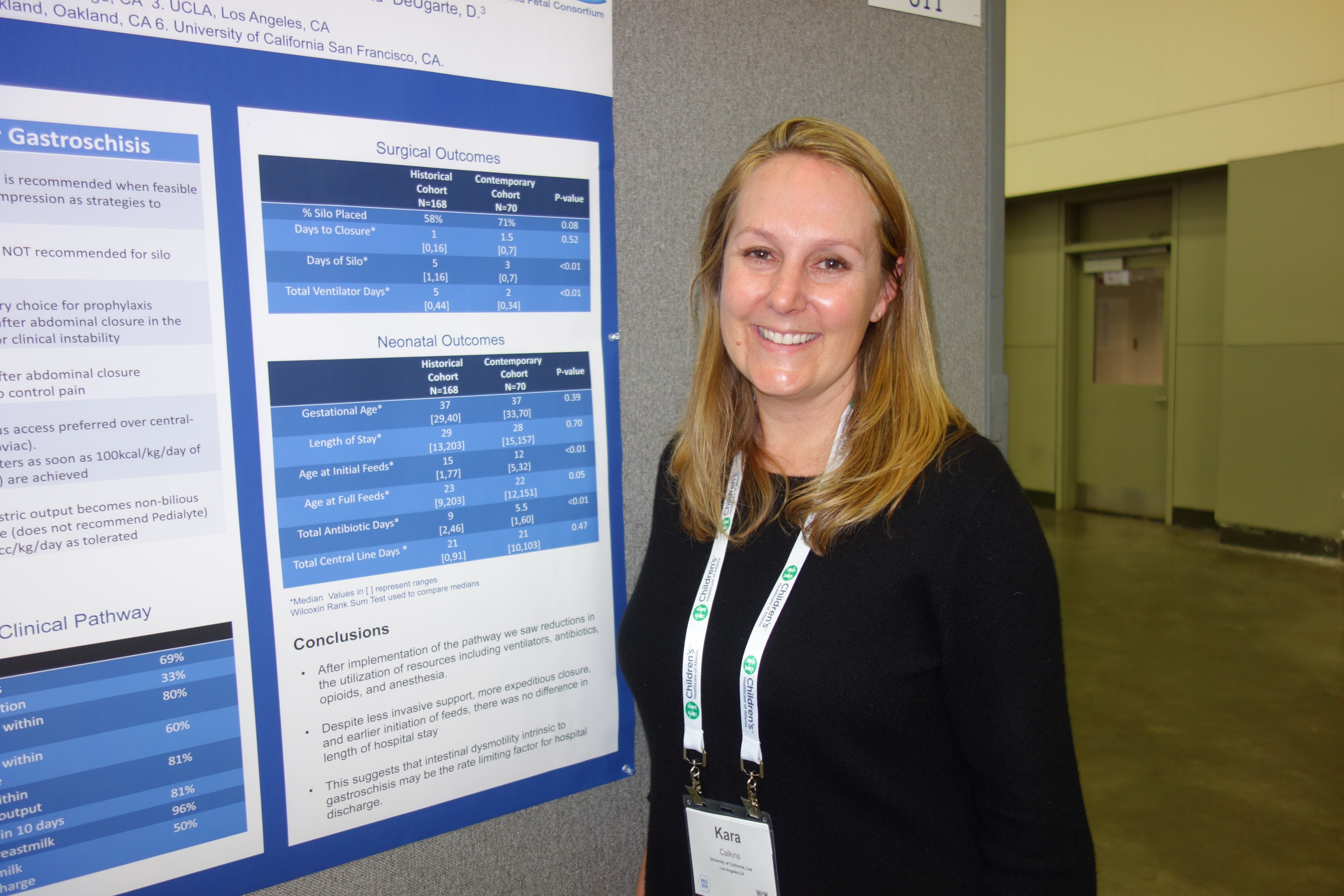

To see how it’s worked out, Dr. Calkins and her colleagues reviewed 70 gastroschisis cases managed under the new guidelines. They were uncomplicated cases, with no intestinal atresia, stricture, or ischemia.

Paralysis was avoided for silo placement in 53 infants (76%) and 32 (46%) avoided intubation. Antibiotics were discontinued in 56 (80%) within 48 hours of abdominal wall closure, and routine narcotics were discontinued in 53 infants (76%). Feeds were initiated in almost all children within 48 hours of non-bilious gastric tube output.

Compared with 168 infants treated before the changes were made, silo placement dropped from 71% to 58% of infants, and total ventilator days from a median of 5 to 2.

There was no difference in length of stay, perhaps because the “intestinal dysmotility intrinsic to gastroschisis remains a rate limiting factor for discharge,” the team concluded.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Calkins didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottkamp CA et al., PAS 2019. Abstract 51.

BALTIMORE – a condition in which infants are born with their intestines and sometimes other organs protruding through a hole beside the umbilicus.

Neonatologists, maternal-fetal health experts, and pediatric surgeons standardized a literature-based approach that was gentler and less invasive than usual management, emphasizing sutureless closure, sometimes at bedside on the first day of life, and early feeding. Often, it turned out, that’s all that children require.

It’s made a big difference. “We reduced the number of trips to the operating room and exposure to general anesthesia. We reduced the number of babies intubated and days on the ventilator. We reduced opioid days and antibiotic days” without increasing bacteremia, and “there are probably long-term benefits beyond the NICU,” said Kara Calkins, MD, at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

I think this is definitely ahead of the curve for NICUs. My hope is that the vast majority of universities adopt a similar approach,” said Dr. Calkins, who is an assistant professor of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“When I was a fellow,” she explained, “we took all of these babies and intubated them right away and put them on a drip to paralyze and sedate them. We put their bowels into a silo,” essentially a plastic bag suspended by a string, in the hopes that gravity would pull the bowels back into the abdomen. More often than not, however, “the surgeon would come by every day and slowly push them” back in over a week or so. “The fear was if you did it too quickly, you’d invoke an abdominal compartment syndrome, or respiratory decompensation. You had a baby intubated for a week, sedated and paralyzed.”

Infants were kept on total parenteral nutrition for weeks, sometimes through a Broviac central catheter.

It was overkill, Dr. Calkins said, when only the intestines are out and the abdominal wall defect isn’t too large or too small, which is the case for many infants.

For those children, sutureless closure over 1-3 days is the new goal. The bowel is worked back into the abdomen and the umbilical cord is pulled to the side to approximate the edges of the wound, and tacked down; the defect then heals itself. Antibiotics are discontinued 48 hours after closure. Gastric and rectal decompression helps with reduction.

Also, “we give drops of breast milk in their cheek right away, every couple of hours starting on the first day of life. Once the output from the gastric tube is clear, we start feeds. We still give total parenteral nutrition, but through a [peripherally inserted central catheter] in the arm,” Dr. Calkins said. “Use of breast milk for this population is important” to help establish a healthy microbiome, among other reasons.

Another improvement that had been made, according to Dr. Calkins, is that if only the intestines are out, women carry their baby to term and deliver vaginally. The old practice was to deliver babies preterm by Cesarean section, she explained.

To see how it’s worked out, Dr. Calkins and her colleagues reviewed 70 gastroschisis cases managed under the new guidelines. They were uncomplicated cases, with no intestinal atresia, stricture, or ischemia.

Paralysis was avoided for silo placement in 53 infants (76%) and 32 (46%) avoided intubation. Antibiotics were discontinued in 56 (80%) within 48 hours of abdominal wall closure, and routine narcotics were discontinued in 53 infants (76%). Feeds were initiated in almost all children within 48 hours of non-bilious gastric tube output.

Compared with 168 infants treated before the changes were made, silo placement dropped from 71% to 58% of infants, and total ventilator days from a median of 5 to 2.

There was no difference in length of stay, perhaps because the “intestinal dysmotility intrinsic to gastroschisis remains a rate limiting factor for discharge,” the team concluded.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Calkins didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottkamp CA et al., PAS 2019. Abstract 51.

BALTIMORE – a condition in which infants are born with their intestines and sometimes other organs protruding through a hole beside the umbilicus.

Neonatologists, maternal-fetal health experts, and pediatric surgeons standardized a literature-based approach that was gentler and less invasive than usual management, emphasizing sutureless closure, sometimes at bedside on the first day of life, and early feeding. Often, it turned out, that’s all that children require.

It’s made a big difference. “We reduced the number of trips to the operating room and exposure to general anesthesia. We reduced the number of babies intubated and days on the ventilator. We reduced opioid days and antibiotic days” without increasing bacteremia, and “there are probably long-term benefits beyond the NICU,” said Kara Calkins, MD, at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

I think this is definitely ahead of the curve for NICUs. My hope is that the vast majority of universities adopt a similar approach,” said Dr. Calkins, who is an assistant professor of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“When I was a fellow,” she explained, “we took all of these babies and intubated them right away and put them on a drip to paralyze and sedate them. We put their bowels into a silo,” essentially a plastic bag suspended by a string, in the hopes that gravity would pull the bowels back into the abdomen. More often than not, however, “the surgeon would come by every day and slowly push them” back in over a week or so. “The fear was if you did it too quickly, you’d invoke an abdominal compartment syndrome, or respiratory decompensation. You had a baby intubated for a week, sedated and paralyzed.”

Infants were kept on total parenteral nutrition for weeks, sometimes through a Broviac central catheter.

It was overkill, Dr. Calkins said, when only the intestines are out and the abdominal wall defect isn’t too large or too small, which is the case for many infants.

For those children, sutureless closure over 1-3 days is the new goal. The bowel is worked back into the abdomen and the umbilical cord is pulled to the side to approximate the edges of the wound, and tacked down; the defect then heals itself. Antibiotics are discontinued 48 hours after closure. Gastric and rectal decompression helps with reduction.

Also, “we give drops of breast milk in their cheek right away, every couple of hours starting on the first day of life. Once the output from the gastric tube is clear, we start feeds. We still give total parenteral nutrition, but through a [peripherally inserted central catheter] in the arm,” Dr. Calkins said. “Use of breast milk for this population is important” to help establish a healthy microbiome, among other reasons.

Another improvement that had been made, according to Dr. Calkins, is that if only the intestines are out, women carry their baby to term and deliver vaginally. The old practice was to deliver babies preterm by Cesarean section, she explained.

To see how it’s worked out, Dr. Calkins and her colleagues reviewed 70 gastroschisis cases managed under the new guidelines. They were uncomplicated cases, with no intestinal atresia, stricture, or ischemia.

Paralysis was avoided for silo placement in 53 infants (76%) and 32 (46%) avoided intubation. Antibiotics were discontinued in 56 (80%) within 48 hours of abdominal wall closure, and routine narcotics were discontinued in 53 infants (76%). Feeds were initiated in almost all children within 48 hours of non-bilious gastric tube output.

Compared with 168 infants treated before the changes were made, silo placement dropped from 71% to 58% of infants, and total ventilator days from a median of 5 to 2.

There was no difference in length of stay, perhaps because the “intestinal dysmotility intrinsic to gastroschisis remains a rate limiting factor for discharge,” the team concluded.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Calkins didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottkamp CA et al., PAS 2019. Abstract 51.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Liraglutide seems safe, effective in children already on metformin

The addition of liraglutide to metformin shows significantly improved glycemic control in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes, compared with metformin alone, according to data presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Baltimore.

The phase 3 study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, involved 134 patients aged 10-17 years with type 2 diabetes who were managing their diabetes with diet and exercise, metformin, or insulin.

Participants were randomized either to subcutaneous liraglutide – dose-escalated up to 1.8 mg/day, depending on efficacy and side effects – or placebo for 52 weeks. The first 26 weeks were double blind and the second 26 weeks were an open-label extension period.

At 26 weeks, mean glycated hemoglobin levels in the liraglutide group had decreased by 0.64 percentage points from baseline, but in the placebo group they had increased by 0.42 percentage points, representing a treatment difference of –1.06 percentage points (P less than .001). By week 52, the treatment difference between the two groups had increased to –1.30 percentage points.

William V. Tamborlane, MD, from the department of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his coauthors wrote that metformin is the approved drug of choice for pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes, and that insulin currently is the only approved option for those who do not have an adequate response to metformin monotherapy.

“This discrepancy in available treatments for youth as compared with adults persists because of a lack of successfully completed trials needed for approval of new drugs for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in children since a trial of metformin was completed in 1999,” they wrote.

The study showed that significantly more patients in the liraglutide group (63.7%) achieved glycated hemoglobin levels below 7%, compared with 36.5% of patients in the placebo group. Fasting plasma glucose levels were decreased in the liraglutide group at both 26 and 52 weeks, but had increased in the placebo group.

Although the number of reported adverse events were similar between the two groups, there were significantly more reports of gastrointestinal adverse events – particularly nausea – in patients taking liraglutide, compared with those on placebo.

However, the study did not show a difference between liraglutide and placebo in lowering body mass index, although mean body weight decreases – which were seen in both groups – were maintained at week 52 only in the liraglutide group. The authors suggested this might be owing to the relatively small number of patients enrolled in the study and that some of the children were still growing.

Novo Nordisk, which manufactures liraglutide, supported the study. Twelve authors reported grants or support from Novo Nordisk in relation to the trial. Three authors were employees of Novo Nordisk. Eight authors reported unrelated grants and fees from Novo Nordisk and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Tamborlane WV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903822.

The addition of liraglutide to metformin shows significantly improved glycemic control in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes, compared with metformin alone, according to data presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Baltimore.

The phase 3 study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, involved 134 patients aged 10-17 years with type 2 diabetes who were managing their diabetes with diet and exercise, metformin, or insulin.

Participants were randomized either to subcutaneous liraglutide – dose-escalated up to 1.8 mg/day, depending on efficacy and side effects – or placebo for 52 weeks. The first 26 weeks were double blind and the second 26 weeks were an open-label extension period.

At 26 weeks, mean glycated hemoglobin levels in the liraglutide group had decreased by 0.64 percentage points from baseline, but in the placebo group they had increased by 0.42 percentage points, representing a treatment difference of –1.06 percentage points (P less than .001). By week 52, the treatment difference between the two groups had increased to –1.30 percentage points.

William V. Tamborlane, MD, from the department of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his coauthors wrote that metformin is the approved drug of choice for pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes, and that insulin currently is the only approved option for those who do not have an adequate response to metformin monotherapy.

“This discrepancy in available treatments for youth as compared with adults persists because of a lack of successfully completed trials needed for approval of new drugs for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in children since a trial of metformin was completed in 1999,” they wrote.

The study showed that significantly more patients in the liraglutide group (63.7%) achieved glycated hemoglobin levels below 7%, compared with 36.5% of patients in the placebo group. Fasting plasma glucose levels were decreased in the liraglutide group at both 26 and 52 weeks, but had increased in the placebo group.

Although the number of reported adverse events were similar between the two groups, there were significantly more reports of gastrointestinal adverse events – particularly nausea – in patients taking liraglutide, compared with those on placebo.

However, the study did not show a difference between liraglutide and placebo in lowering body mass index, although mean body weight decreases – which were seen in both groups – were maintained at week 52 only in the liraglutide group. The authors suggested this might be owing to the relatively small number of patients enrolled in the study and that some of the children were still growing.

Novo Nordisk, which manufactures liraglutide, supported the study. Twelve authors reported grants or support from Novo Nordisk in relation to the trial. Three authors were employees of Novo Nordisk. Eight authors reported unrelated grants and fees from Novo Nordisk and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Tamborlane WV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903822.

The addition of liraglutide to metformin shows significantly improved glycemic control in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes, compared with metformin alone, according to data presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Baltimore.

The phase 3 study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, involved 134 patients aged 10-17 years with type 2 diabetes who were managing their diabetes with diet and exercise, metformin, or insulin.

Participants were randomized either to subcutaneous liraglutide – dose-escalated up to 1.8 mg/day, depending on efficacy and side effects – or placebo for 52 weeks. The first 26 weeks were double blind and the second 26 weeks were an open-label extension period.

At 26 weeks, mean glycated hemoglobin levels in the liraglutide group had decreased by 0.64 percentage points from baseline, but in the placebo group they had increased by 0.42 percentage points, representing a treatment difference of –1.06 percentage points (P less than .001). By week 52, the treatment difference between the two groups had increased to –1.30 percentage points.

William V. Tamborlane, MD, from the department of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his coauthors wrote that metformin is the approved drug of choice for pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes, and that insulin currently is the only approved option for those who do not have an adequate response to metformin monotherapy.

“This discrepancy in available treatments for youth as compared with adults persists because of a lack of successfully completed trials needed for approval of new drugs for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in children since a trial of metformin was completed in 1999,” they wrote.

The study showed that significantly more patients in the liraglutide group (63.7%) achieved glycated hemoglobin levels below 7%, compared with 36.5% of patients in the placebo group. Fasting plasma glucose levels were decreased in the liraglutide group at both 26 and 52 weeks, but had increased in the placebo group.

Although the number of reported adverse events were similar between the two groups, there were significantly more reports of gastrointestinal adverse events – particularly nausea – in patients taking liraglutide, compared with those on placebo.

However, the study did not show a difference between liraglutide and placebo in lowering body mass index, although mean body weight decreases – which were seen in both groups – were maintained at week 52 only in the liraglutide group. The authors suggested this might be owing to the relatively small number of patients enrolled in the study and that some of the children were still growing.

Novo Nordisk, which manufactures liraglutide, supported the study. Twelve authors reported grants or support from Novo Nordisk in relation to the trial. Three authors were employees of Novo Nordisk. Eight authors reported unrelated grants and fees from Novo Nordisk and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Tamborlane WV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903822.

FROM PAS 2019

No benefit to infants from e-books over board books

BALTIMORE – Despite the greater portability and seeming convenience of electronic tablets or smartphones, compared with giving them physical board books, according to preliminary findings.

James Guevara, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, presented his findings at the annual meeting of Pediatric Academic Societies in a session focused on the changing nature of children’s digital media use as digital natives.

The session chair, Danielle C. Erkoboni, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, opened the session with a review of research to date regarding children’s frequency of digital use and relative benefits of independent and shared reading, both with traditional books and e-books.

Nearly all U.S. children (98%) live in homes with mobile devices, and about a third of U.S. children (35%) use those devices, according to a 2017 Common Sense Media Report. The same survey found that children aged under 2 years get an average 42 minutes a day of overall screen time, but children in low-income households get twice as much screen time as those in middle- and upper-income homes.

Research into e-books exists for preschoolers, showing that animated pictures and sounds directly matching an e-book’s story text can potentially promote language memory, but that too many interactive features or other bells and whistles can overwhelm children and contribute to poor vocabulary development and comprehension.

Researchers also have found that parent reading of e-books has greater benefits for children than children listening to an e-book’s audio narration. However, little to no research has looked into e-reading for infants and toddlers, a gap especially relevant for physicians who participate in the Reach Out and Read program.

Dr Guevara’s study enrolled 100 Medicaid-eligible children aged 5-7 months from three participating practices in a single geographic area. Only English- or Spanish-speaking parents who owned a smartphone or tablet participated.

At the children’s 6-month well visit, the clinicians gave parents information about the importance of early parent-child reading. Then parents received Dr. Seuss’s “Hop on Pop” as either an e-book download (n = 45) or a physical board book (n = 54). The parents similarly received “Barnyard Dance” at the 9-month visit and “Goodnight Moon” at the 12-month visit.

No significant differences between the two groups existed in terms of race/ethnicity, parent age, household income, education level, marital status or the total number of adults or children in the household. Maternal depression rates (based on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale), Adverse Childhood Experience scale scores, health literacy scores (Short Assessment of Health Literacy) and scores on the StimQ home cognitive environment assessment also were similar at baseline between the two groups.

The children were assessed with the StimQ Infant measure at 7-8 months and 10-11 months, and then with the StimQ Toddler and Bayley Scale of Infant and Toddler Development (BSID-III) at 13-15 months. At the final check-up, 37 parents remained in the e-book group and 43 parents remained in the board book group.

A similar proportion of parents in both groups reported reading to their children, and parents in both groups said they read an average of 5 days a week to their child.

However, parents who received the e-books had read an average 18 books at the final follow-up, compared with an average of 31 books among parents who received the board books (P = .039).

No significant differences in children’s StimQ scores or any of the BSID-III scores (cognitive, language, motor) existed between those who received e-books versus those who received board books.

The study results showed the feasibility of promoting literacy by providing e-books to parents of older infants, but doing so did not appear to confer any advantage over providing families with traditional, physical board books. Further, language development among children in both groups remained below average, albeit not statistically different from one another.

“Pediatric clinicians should exercise caution in recommending e-books to parents of young children.” Dr Guevara said. “Additional strategies beyond clinic-based literacy promotion are needed to enhance language development among poor children.”

The research was funded by the Vanguard Strong Start for Kids Program. Dr. Guevara reported no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Despite the greater portability and seeming convenience of electronic tablets or smartphones, compared with giving them physical board books, according to preliminary findings.

James Guevara, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, presented his findings at the annual meeting of Pediatric Academic Societies in a session focused on the changing nature of children’s digital media use as digital natives.

The session chair, Danielle C. Erkoboni, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, opened the session with a review of research to date regarding children’s frequency of digital use and relative benefits of independent and shared reading, both with traditional books and e-books.

Nearly all U.S. children (98%) live in homes with mobile devices, and about a third of U.S. children (35%) use those devices, according to a 2017 Common Sense Media Report. The same survey found that children aged under 2 years get an average 42 minutes a day of overall screen time, but children in low-income households get twice as much screen time as those in middle- and upper-income homes.

Research into e-books exists for preschoolers, showing that animated pictures and sounds directly matching an e-book’s story text can potentially promote language memory, but that too many interactive features or other bells and whistles can overwhelm children and contribute to poor vocabulary development and comprehension.

Researchers also have found that parent reading of e-books has greater benefits for children than children listening to an e-book’s audio narration. However, little to no research has looked into e-reading for infants and toddlers, a gap especially relevant for physicians who participate in the Reach Out and Read program.

Dr Guevara’s study enrolled 100 Medicaid-eligible children aged 5-7 months from three participating practices in a single geographic area. Only English- or Spanish-speaking parents who owned a smartphone or tablet participated.

At the children’s 6-month well visit, the clinicians gave parents information about the importance of early parent-child reading. Then parents received Dr. Seuss’s “Hop on Pop” as either an e-book download (n = 45) or a physical board book (n = 54). The parents similarly received “Barnyard Dance” at the 9-month visit and “Goodnight Moon” at the 12-month visit.

No significant differences between the two groups existed in terms of race/ethnicity, parent age, household income, education level, marital status or the total number of adults or children in the household. Maternal depression rates (based on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale), Adverse Childhood Experience scale scores, health literacy scores (Short Assessment of Health Literacy) and scores on the StimQ home cognitive environment assessment also were similar at baseline between the two groups.

The children were assessed with the StimQ Infant measure at 7-8 months and 10-11 months, and then with the StimQ Toddler and Bayley Scale of Infant and Toddler Development (BSID-III) at 13-15 months. At the final check-up, 37 parents remained in the e-book group and 43 parents remained in the board book group.

A similar proportion of parents in both groups reported reading to their children, and parents in both groups said they read an average of 5 days a week to their child.

However, parents who received the e-books had read an average 18 books at the final follow-up, compared with an average of 31 books among parents who received the board books (P = .039).

No significant differences in children’s StimQ scores or any of the BSID-III scores (cognitive, language, motor) existed between those who received e-books versus those who received board books.

The study results showed the feasibility of promoting literacy by providing e-books to parents of older infants, but doing so did not appear to confer any advantage over providing families with traditional, physical board books. Further, language development among children in both groups remained below average, albeit not statistically different from one another.

“Pediatric clinicians should exercise caution in recommending e-books to parents of young children.” Dr Guevara said. “Additional strategies beyond clinic-based literacy promotion are needed to enhance language development among poor children.”

The research was funded by the Vanguard Strong Start for Kids Program. Dr. Guevara reported no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Despite the greater portability and seeming convenience of electronic tablets or smartphones, compared with giving them physical board books, according to preliminary findings.

James Guevara, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, presented his findings at the annual meeting of Pediatric Academic Societies in a session focused on the changing nature of children’s digital media use as digital natives.

The session chair, Danielle C. Erkoboni, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, opened the session with a review of research to date regarding children’s frequency of digital use and relative benefits of independent and shared reading, both with traditional books and e-books.

Nearly all U.S. children (98%) live in homes with mobile devices, and about a third of U.S. children (35%) use those devices, according to a 2017 Common Sense Media Report. The same survey found that children aged under 2 years get an average 42 minutes a day of overall screen time, but children in low-income households get twice as much screen time as those in middle- and upper-income homes.

Research into e-books exists for preschoolers, showing that animated pictures and sounds directly matching an e-book’s story text can potentially promote language memory, but that too many interactive features or other bells and whistles can overwhelm children and contribute to poor vocabulary development and comprehension.

Researchers also have found that parent reading of e-books has greater benefits for children than children listening to an e-book’s audio narration. However, little to no research has looked into e-reading for infants and toddlers, a gap especially relevant for physicians who participate in the Reach Out and Read program.

Dr Guevara’s study enrolled 100 Medicaid-eligible children aged 5-7 months from three participating practices in a single geographic area. Only English- or Spanish-speaking parents who owned a smartphone or tablet participated.

At the children’s 6-month well visit, the clinicians gave parents information about the importance of early parent-child reading. Then parents received Dr. Seuss’s “Hop on Pop” as either an e-book download (n = 45) or a physical board book (n = 54). The parents similarly received “Barnyard Dance” at the 9-month visit and “Goodnight Moon” at the 12-month visit.

No significant differences between the two groups existed in terms of race/ethnicity, parent age, household income, education level, marital status or the total number of adults or children in the household. Maternal depression rates (based on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale), Adverse Childhood Experience scale scores, health literacy scores (Short Assessment of Health Literacy) and scores on the StimQ home cognitive environment assessment also were similar at baseline between the two groups.

The children were assessed with the StimQ Infant measure at 7-8 months and 10-11 months, and then with the StimQ Toddler and Bayley Scale of Infant and Toddler Development (BSID-III) at 13-15 months. At the final check-up, 37 parents remained in the e-book group and 43 parents remained in the board book group.

A similar proportion of parents in both groups reported reading to their children, and parents in both groups said they read an average of 5 days a week to their child.

However, parents who received the e-books had read an average 18 books at the final follow-up, compared with an average of 31 books among parents who received the board books (P = .039).

No significant differences in children’s StimQ scores or any of the BSID-III scores (cognitive, language, motor) existed between those who received e-books versus those who received board books.

The study results showed the feasibility of promoting literacy by providing e-books to parents of older infants, but doing so did not appear to confer any advantage over providing families with traditional, physical board books. Further, language development among children in both groups remained below average, albeit not statistically different from one another.

“Pediatric clinicians should exercise caution in recommending e-books to parents of young children.” Dr Guevara said. “Additional strategies beyond clinic-based literacy promotion are needed to enhance language development among poor children.”

The research was funded by the Vanguard Strong Start for Kids Program. Dr. Guevara reported no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Parents’ smartphone addiction linked to children’s overuse of the devices

BALTIMORE – according to a new study. The findings suggest that excessive smartphone use also is associated with the stress of parenting.

“We really need to start raising awareness among parents that their behaviors possibly have an association with their children’s [behaviors] as well,” lead author Korena S. Klimczak of Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Va., said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“I think a lot of parents are not really considering how their smartphone use might be possibly influencing their children,” Ms. Klimczak said. “I think that’s an area pediatricians can start to target as they see parents using the smartphone in the room or passing the phone off to their child in the room.”

Previous research already has linked excessive smartphone use with problematic parenting. Parents distracted by their phones tend to communicate less with their children in the moment, and parents with smartphone addiction symptoms are “less likely to actively mediate their child’s smartphone use,” Ms. Klimczak and her associates noted.

For this study, the researchers recruited 355 parents of children aged 6 months to 5 years from an urban Southeastern academic pediatric hospital clinic. Most of the participating parents were black (72%) and most were mothers (79%).

During a well-child visit, the parents filled out the Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS), the Parental Stress Scale (PSS) and a 16-item survey on their demographics and their children’s smartphone use. The SAS provided a binary variable (yes/no) on whether parents were addicted to their phones.

Starting when the children were between 12 and 17 months old, parents reported their children’s increasing ability to open or turn on a smartphone. Forty percent of parents reported that their children could turn on phones at this age, and the proportion steadily rose to 79% for children aged 4-5 years (P less than .001).

About one-third of children could start applications on their parents’ phones at age 12-17 months, but more than half were watching videos on their parents’ phones at that age. By the time children were aged 18-24 months, 73% of parents reported that the toddlers could open applications on the phones.

Among parents with a smartphone addiction as defined by the SAS, 59% reported finding it difficult to take their phones away from their children, compared with about half as many parents (26%) without a smartphone addiction (P = .001).

That finding appeared to carry over into their children spending more time on their smartphones as well. Among parents with a smartphone addiction, 22% reported that their children spent more than 2 hours a day on their smartphones, compared with 4% of parents without a smartphone addiction (P = .012). Past research suggests that spending that much time on mobile phones can be an obstacle to emotional and cognitive development, Ms. Klimczak said.

The proportion of children who spent time on their parents’ phones for 5-30 minutes, 30-60 minutes, or 1-2 hours was otherwise relatively similar between parents with and without smartphone addiction.

“There were some possible behavioral issues involved with smartphone addiction in parents as well,” she said, given how much more difficulty these parents had with taking phones away from their children. These parents “were more likely to use corporal punishment as well,” she added.

When faced with a hypothetical situation in which the child broke the parent’s phone, parents with high levels of parental stress were “significantly more likely to discipline their child through either spanking or yelling” the researchers reported, and a positive correlation between parental stress and smartphone addiction existed as well (r = .352, P less than .001).

Ms. Klimczak acknowledged that pediatricians already have a lot of ground to cover in each well-child visit, and monitoring parents’ cell phone use does not necessarily need to be a formal screening measure.

“I think as you see the behavior, you can point it out and maybe gently bring it up,” she said. Pediatricians who notice parents focused on their phones or passing their phones to their children can ask parents at that moment: “I see you using your phone ...” or “I see you’re letting your child use the phone. How often do you let them use the phone [each] day?” Ms. Klimczak said. Gently asking those questions may at least get the parents to think about the issues.

She also recommended incorporating awareness of smartphone addiction and child use of phones into parent education programs in addition to information about safe sleep, breastfeeding, and similar topics. “With how prevalent smartphone use is today, I think it’s at least something to bring up and make them conscious of.”

Ms. Klimczak had no financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – according to a new study. The findings suggest that excessive smartphone use also is associated with the stress of parenting.

“We really need to start raising awareness among parents that their behaviors possibly have an association with their children’s [behaviors] as well,” lead author Korena S. Klimczak of Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Va., said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“I think a lot of parents are not really considering how their smartphone use might be possibly influencing their children,” Ms. Klimczak said. “I think that’s an area pediatricians can start to target as they see parents using the smartphone in the room or passing the phone off to their child in the room.”

Previous research already has linked excessive smartphone use with problematic parenting. Parents distracted by their phones tend to communicate less with their children in the moment, and parents with smartphone addiction symptoms are “less likely to actively mediate their child’s smartphone use,” Ms. Klimczak and her associates noted.

For this study, the researchers recruited 355 parents of children aged 6 months to 5 years from an urban Southeastern academic pediatric hospital clinic. Most of the participating parents were black (72%) and most were mothers (79%).

During a well-child visit, the parents filled out the Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS), the Parental Stress Scale (PSS) and a 16-item survey on their demographics and their children’s smartphone use. The SAS provided a binary variable (yes/no) on whether parents were addicted to their phones.

Starting when the children were between 12 and 17 months old, parents reported their children’s increasing ability to open or turn on a smartphone. Forty percent of parents reported that their children could turn on phones at this age, and the proportion steadily rose to 79% for children aged 4-5 years (P less than .001).

About one-third of children could start applications on their parents’ phones at age 12-17 months, but more than half were watching videos on their parents’ phones at that age. By the time children were aged 18-24 months, 73% of parents reported that the toddlers could open applications on the phones.

Among parents with a smartphone addiction as defined by the SAS, 59% reported finding it difficult to take their phones away from their children, compared with about half as many parents (26%) without a smartphone addiction (P = .001).

That finding appeared to carry over into their children spending more time on their smartphones as well. Among parents with a smartphone addiction, 22% reported that their children spent more than 2 hours a day on their smartphones, compared with 4% of parents without a smartphone addiction (P = .012). Past research suggests that spending that much time on mobile phones can be an obstacle to emotional and cognitive development, Ms. Klimczak said.

The proportion of children who spent time on their parents’ phones for 5-30 minutes, 30-60 minutes, or 1-2 hours was otherwise relatively similar between parents with and without smartphone addiction.

“There were some possible behavioral issues involved with smartphone addiction in parents as well,” she said, given how much more difficulty these parents had with taking phones away from their children. These parents “were more likely to use corporal punishment as well,” she added.

When faced with a hypothetical situation in which the child broke the parent’s phone, parents with high levels of parental stress were “significantly more likely to discipline their child through either spanking or yelling” the researchers reported, and a positive correlation between parental stress and smartphone addiction existed as well (r = .352, P less than .001).

Ms. Klimczak acknowledged that pediatricians already have a lot of ground to cover in each well-child visit, and monitoring parents’ cell phone use does not necessarily need to be a formal screening measure.

“I think as you see the behavior, you can point it out and maybe gently bring it up,” she said. Pediatricians who notice parents focused on their phones or passing their phones to their children can ask parents at that moment: “I see you using your phone ...” or “I see you’re letting your child use the phone. How often do you let them use the phone [each] day?” Ms. Klimczak said. Gently asking those questions may at least get the parents to think about the issues.

She also recommended incorporating awareness of smartphone addiction and child use of phones into parent education programs in addition to information about safe sleep, breastfeeding, and similar topics. “With how prevalent smartphone use is today, I think it’s at least something to bring up and make them conscious of.”

Ms. Klimczak had no financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – according to a new study. The findings suggest that excessive smartphone use also is associated with the stress of parenting.

“We really need to start raising awareness among parents that their behaviors possibly have an association with their children’s [behaviors] as well,” lead author Korena S. Klimczak of Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Va., said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“I think a lot of parents are not really considering how their smartphone use might be possibly influencing their children,” Ms. Klimczak said. “I think that’s an area pediatricians can start to target as they see parents using the smartphone in the room or passing the phone off to their child in the room.”

Previous research already has linked excessive smartphone use with problematic parenting. Parents distracted by their phones tend to communicate less with their children in the moment, and parents with smartphone addiction symptoms are “less likely to actively mediate their child’s smartphone use,” Ms. Klimczak and her associates noted.

For this study, the researchers recruited 355 parents of children aged 6 months to 5 years from an urban Southeastern academic pediatric hospital clinic. Most of the participating parents were black (72%) and most were mothers (79%).

During a well-child visit, the parents filled out the Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS), the Parental Stress Scale (PSS) and a 16-item survey on their demographics and their children’s smartphone use. The SAS provided a binary variable (yes/no) on whether parents were addicted to their phones.

Starting when the children were between 12 and 17 months old, parents reported their children’s increasing ability to open or turn on a smartphone. Forty percent of parents reported that their children could turn on phones at this age, and the proportion steadily rose to 79% for children aged 4-5 years (P less than .001).

About one-third of children could start applications on their parents’ phones at age 12-17 months, but more than half were watching videos on their parents’ phones at that age. By the time children were aged 18-24 months, 73% of parents reported that the toddlers could open applications on the phones.

Among parents with a smartphone addiction as defined by the SAS, 59% reported finding it difficult to take their phones away from their children, compared with about half as many parents (26%) without a smartphone addiction (P = .001).

That finding appeared to carry over into their children spending more time on their smartphones as well. Among parents with a smartphone addiction, 22% reported that their children spent more than 2 hours a day on their smartphones, compared with 4% of parents without a smartphone addiction (P = .012). Past research suggests that spending that much time on mobile phones can be an obstacle to emotional and cognitive development, Ms. Klimczak said.

The proportion of children who spent time on their parents’ phones for 5-30 minutes, 30-60 minutes, or 1-2 hours was otherwise relatively similar between parents with and without smartphone addiction.

“There were some possible behavioral issues involved with smartphone addiction in parents as well,” she said, given how much more difficulty these parents had with taking phones away from their children. These parents “were more likely to use corporal punishment as well,” she added.

When faced with a hypothetical situation in which the child broke the parent’s phone, parents with high levels of parental stress were “significantly more likely to discipline their child through either spanking or yelling” the researchers reported, and a positive correlation between parental stress and smartphone addiction existed as well (r = .352, P less than .001).

Ms. Klimczak acknowledged that pediatricians already have a lot of ground to cover in each well-child visit, and monitoring parents’ cell phone use does not necessarily need to be a formal screening measure.

“I think as you see the behavior, you can point it out and maybe gently bring it up,” she said. Pediatricians who notice parents focused on their phones or passing their phones to their children can ask parents at that moment: “I see you using your phone ...” or “I see you’re letting your child use the phone. How often do you let them use the phone [each] day?” Ms. Klimczak said. Gently asking those questions may at least get the parents to think about the issues.

She also recommended incorporating awareness of smartphone addiction and child use of phones into parent education programs in addition to information about safe sleep, breastfeeding, and similar topics. “With how prevalent smartphone use is today, I think it’s at least something to bring up and make them conscious of.”

Ms. Klimczak had no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Zika knowledge, preparedness low among U.S. pediatricians

BALTIMORE – U.S. pediatricians feel comfortable providing patients with preventive information and travel advice related to Zika, but few feel prepared when it comes to testing and management of infants exposed prenatally to Zika infections, a study found.

“Areas where pediatricians were less likely to report preparedness included recommending testing, providing data to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Zika Pregnancy Registry, managing infants exposed to Zika prenatally, and informing parents of social services for Zika-infected infants,” senior author Amy J. Houtrow, MD, MPH, PhD, and colleagues reported at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“Results indicate that additional education efforts are needed to grow the overall Zika knowledge of pediatricians and boost preparedness, particularly around recommending Zika testing and providing data to CDC,” they concluded.

But these findings are not surprising given how rare congenital Zika virus syndrome is, explained Dr. Houtrow, an associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh.

“For most rare conditions, pediatricians report better general than specific knowledge,” Dr. Houtrow said in an interview. “We expect pediatricians have a broad range of knowledge for a multitude of conditions and to be well versed in the care of infants and children with common conditions, coupled with the ability to access knowledge and expertise about rarer conditions such as congenital Zika syndrome.”

Dr. Houtrow and associates drew their findings from the 2018 AAP Periodic Survey of Fellows, which includes both primary care physicians and neonatologists. The survey’s response rate was 42%, with 672 of 1,599 surveys returned, but the researchers limited their analysis to 576 postresidency respondents who were providing direct patient care.

Overall, 39% of physicians reported being knowledgeable about Zika virus, and 47% said they wanted to learn more. More than half of responding doctors (57%) reported feeling moderately or very prepared when it came to informing patients of preventive measures to reduce risk of Zika infection, and nearly half (49%) felt confident about giving patients travel advice.

However, physicians’ preparedness gradually dropped for clinical situations requiring more direct experience with Zika. For example, 37% felt moderately or very prepared to provide clinical referrals for infant patients with an infection, and 33% felt prepared to talk with pregnant women about the risks of birth defects from Zika infection.

Just one in five physicians (22%) felt prepared for recommending Zika virus testing, and 16% felt prepared about providing data to the CDC’s U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry or managing infants who had been prenatally exposed to Zika infection. Only 15% felt they had the preparedness to tell parents about social services for Zika-affected infants.

Preparedness did not differ by gender, specialty, practice setting, hours worked per week, or population density (urban, rural and suburban). However, differences did appear based on respondents’ age and U.S. region.

Older doctors reported greater knowledge about Zika than younger doctors. Compared with those aged 39 years or younger, those aged 40-49 and 50-59 reported feeling more knowledgeable (adjusted odds ratio, 1.74 and 1.72, respectively; P less than .05). The odds of feeling more knowledgeable was nearly triple among those aged at least 60 years, compared with those under 40 (aOR, 2.92; P less than .001).

Those practicing in the Northeast United States (aOR, 2.19; P less than .01) and in the South (aOR, 1.74; P less than .05) also reported feeling more knowledgeable than those in the West or Midwest.

“This makes sense because infants with a history of prenatal exposure to the Zika Virus are more likely to be seen in practices with more immigrants from the Caribbean and Latin America,” Dr. Houtrow said in an interview.

“ but the urgency of the need for education about Zika virus has diminished because the rates of new congenital Zika syndrome have dropped,” she continued.

Study limitations include the inability to generalize the findings beyond U.S. members of the AAP and the possibility that nonrespondents differed from respondents in terms of Zika knowledge and preparedness.

The research was funded by the AAP and CDC.

BALTIMORE – U.S. pediatricians feel comfortable providing patients with preventive information and travel advice related to Zika, but few feel prepared when it comes to testing and management of infants exposed prenatally to Zika infections, a study found.

“Areas where pediatricians were less likely to report preparedness included recommending testing, providing data to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Zika Pregnancy Registry, managing infants exposed to Zika prenatally, and informing parents of social services for Zika-infected infants,” senior author Amy J. Houtrow, MD, MPH, PhD, and colleagues reported at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“Results indicate that additional education efforts are needed to grow the overall Zika knowledge of pediatricians and boost preparedness, particularly around recommending Zika testing and providing data to CDC,” they concluded.

But these findings are not surprising given how rare congenital Zika virus syndrome is, explained Dr. Houtrow, an associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh.

“For most rare conditions, pediatricians report better general than specific knowledge,” Dr. Houtrow said in an interview. “We expect pediatricians have a broad range of knowledge for a multitude of conditions and to be well versed in the care of infants and children with common conditions, coupled with the ability to access knowledge and expertise about rarer conditions such as congenital Zika syndrome.”

Dr. Houtrow and associates drew their findings from the 2018 AAP Periodic Survey of Fellows, which includes both primary care physicians and neonatologists. The survey’s response rate was 42%, with 672 of 1,599 surveys returned, but the researchers limited their analysis to 576 postresidency respondents who were providing direct patient care.

Overall, 39% of physicians reported being knowledgeable about Zika virus, and 47% said they wanted to learn more. More than half of responding doctors (57%) reported feeling moderately or very prepared when it came to informing patients of preventive measures to reduce risk of Zika infection, and nearly half (49%) felt confident about giving patients travel advice.

However, physicians’ preparedness gradually dropped for clinical situations requiring more direct experience with Zika. For example, 37% felt moderately or very prepared to provide clinical referrals for infant patients with an infection, and 33% felt prepared to talk with pregnant women about the risks of birth defects from Zika infection.

Just one in five physicians (22%) felt prepared for recommending Zika virus testing, and 16% felt prepared about providing data to the CDC’s U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry or managing infants who had been prenatally exposed to Zika infection. Only 15% felt they had the preparedness to tell parents about social services for Zika-affected infants.

Preparedness did not differ by gender, specialty, practice setting, hours worked per week, or population density (urban, rural and suburban). However, differences did appear based on respondents’ age and U.S. region.

Older doctors reported greater knowledge about Zika than younger doctors. Compared with those aged 39 years or younger, those aged 40-49 and 50-59 reported feeling more knowledgeable (adjusted odds ratio, 1.74 and 1.72, respectively; P less than .05). The odds of feeling more knowledgeable was nearly triple among those aged at least 60 years, compared with those under 40 (aOR, 2.92; P less than .001).

Those practicing in the Northeast United States (aOR, 2.19; P less than .01) and in the South (aOR, 1.74; P less than .05) also reported feeling more knowledgeable than those in the West or Midwest.

“This makes sense because infants with a history of prenatal exposure to the Zika Virus are more likely to be seen in practices with more immigrants from the Caribbean and Latin America,” Dr. Houtrow said in an interview.

“ but the urgency of the need for education about Zika virus has diminished because the rates of new congenital Zika syndrome have dropped,” she continued.

Study limitations include the inability to generalize the findings beyond U.S. members of the AAP and the possibility that nonrespondents differed from respondents in terms of Zika knowledge and preparedness.

The research was funded by the AAP and CDC.

BALTIMORE – U.S. pediatricians feel comfortable providing patients with preventive information and travel advice related to Zika, but few feel prepared when it comes to testing and management of infants exposed prenatally to Zika infections, a study found.

“Areas where pediatricians were less likely to report preparedness included recommending testing, providing data to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Zika Pregnancy Registry, managing infants exposed to Zika prenatally, and informing parents of social services for Zika-infected infants,” senior author Amy J. Houtrow, MD, MPH, PhD, and colleagues reported at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“Results indicate that additional education efforts are needed to grow the overall Zika knowledge of pediatricians and boost preparedness, particularly around recommending Zika testing and providing data to CDC,” they concluded.

But these findings are not surprising given how rare congenital Zika virus syndrome is, explained Dr. Houtrow, an associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh.

“For most rare conditions, pediatricians report better general than specific knowledge,” Dr. Houtrow said in an interview. “We expect pediatricians have a broad range of knowledge for a multitude of conditions and to be well versed in the care of infants and children with common conditions, coupled with the ability to access knowledge and expertise about rarer conditions such as congenital Zika syndrome.”

Dr. Houtrow and associates drew their findings from the 2018 AAP Periodic Survey of Fellows, which includes both primary care physicians and neonatologists. The survey’s response rate was 42%, with 672 of 1,599 surveys returned, but the researchers limited their analysis to 576 postresidency respondents who were providing direct patient care.

Overall, 39% of physicians reported being knowledgeable about Zika virus, and 47% said they wanted to learn more. More than half of responding doctors (57%) reported feeling moderately or very prepared when it came to informing patients of preventive measures to reduce risk of Zika infection, and nearly half (49%) felt confident about giving patients travel advice.

However, physicians’ preparedness gradually dropped for clinical situations requiring more direct experience with Zika. For example, 37% felt moderately or very prepared to provide clinical referrals for infant patients with an infection, and 33% felt prepared to talk with pregnant women about the risks of birth defects from Zika infection.

Just one in five physicians (22%) felt prepared for recommending Zika virus testing, and 16% felt prepared about providing data to the CDC’s U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry or managing infants who had been prenatally exposed to Zika infection. Only 15% felt they had the preparedness to tell parents about social services for Zika-affected infants.

Preparedness did not differ by gender, specialty, practice setting, hours worked per week, or population density (urban, rural and suburban). However, differences did appear based on respondents’ age and U.S. region.

Older doctors reported greater knowledge about Zika than younger doctors. Compared with those aged 39 years or younger, those aged 40-49 and 50-59 reported feeling more knowledgeable (adjusted odds ratio, 1.74 and 1.72, respectively; P less than .05). The odds of feeling more knowledgeable was nearly triple among those aged at least 60 years, compared with those under 40 (aOR, 2.92; P less than .001).

Those practicing in the Northeast United States (aOR, 2.19; P less than .01) and in the South (aOR, 1.74; P less than .05) also reported feeling more knowledgeable than those in the West or Midwest.

“This makes sense because infants with a history of prenatal exposure to the Zika Virus are more likely to be seen in practices with more immigrants from the Caribbean and Latin America,” Dr. Houtrow said in an interview.

“ but the urgency of the need for education about Zika virus has diminished because the rates of new congenital Zika syndrome have dropped,” she continued.

Study limitations include the inability to generalize the findings beyond U.S. members of the AAP and the possibility that nonrespondents differed from respondents in terms of Zika knowledge and preparedness.

The research was funded by the AAP and CDC.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Combo respiratory pathogen tests miss pertussis

BALTIMORE – Ann Arbor.

Respiratory pathogen panels are popular because they test for many things at once, but providers have to know their limits, said lead investigator Colleen Mayhew, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at the University of Michigan.

“Should RPAN be used to diagnosis pertussis? No,” she said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. RPAN was negative for confirmed pertussis 44% of the time in the study.

“In our cohort, [it] was no better than a coin flip for detecting pertussis,” she said. Also, even when it missed pertussis, it still detected other pathogens, which raises the risk that symptoms might be attributed to a different infection. “This has serious public health implications.”

“The bottom line is, if you are concerned about pertussis, it’s important to use a dedicated pertussis PCR [polymerase chain reaction] assay, and to use comprehensive respiratory pathogen testing only if there are other, specific targets that will change your clinical management,” such as mycoplasma or the flu, Dr. Mayhew said.

In the study, 102 nasopharyngeal swabs positive for pertussis on standalone PCR testing – the university uses an assay from Focus Diagnostics – were thawed and tested with RPAN.

RPAN was negative for pertussis on 45 swabs (44%). “These are the potential missed pertussis cases if RPAN is used alone,” Dr. Mayhew said. RPAN detected other pathogens, such as coronavirus, about half the time, whether or not it tested positive for pertussis. “Those additional pathogens might represent coinfection, but might also represent asymptomatic carriage.” It’s impossible to differentiate between the two, she noted.

In short, “neither positive testing for other respiratory pathogens, nor negative testing for pertussis by RPAN, is reliable for excluding the diagnosis of pertussis. Dedicated pertussis PCR testing should be used for diagnosis,” she and her team concluded.

RPAN also is a PCR test, but with a different, perhaps less robust, genetic target.

The 102 positive swabs were from patients aged 1 month to 73 years, so “it’s important for all of us to keep pertussis on our differential diagnose” no matter how old patients are, Dr. Mayhew said.

Freezing and thawing the swabs shouldn’t have degraded the genetic material, but it might have; that was one of the limits of the study.

The team hopes to run a quality improvement project to encourage the use of standalone pertussis PCR in Ann Arbor.

There was no industry funding. Dr. Mayhew didn’t report any disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Ann Arbor.

Respiratory pathogen panels are popular because they test for many things at once, but providers have to know their limits, said lead investigator Colleen Mayhew, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at the University of Michigan.

“Should RPAN be used to diagnosis pertussis? No,” she said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. RPAN was negative for confirmed pertussis 44% of the time in the study.

“In our cohort, [it] was no better than a coin flip for detecting pertussis,” she said. Also, even when it missed pertussis, it still detected other pathogens, which raises the risk that symptoms might be attributed to a different infection. “This has serious public health implications.”

“The bottom line is, if you are concerned about pertussis, it’s important to use a dedicated pertussis PCR [polymerase chain reaction] assay, and to use comprehensive respiratory pathogen testing only if there are other, specific targets that will change your clinical management,” such as mycoplasma or the flu, Dr. Mayhew said.

In the study, 102 nasopharyngeal swabs positive for pertussis on standalone PCR testing – the university uses an assay from Focus Diagnostics – were thawed and tested with RPAN.