User login

Helping adolescents get enough quality sleep

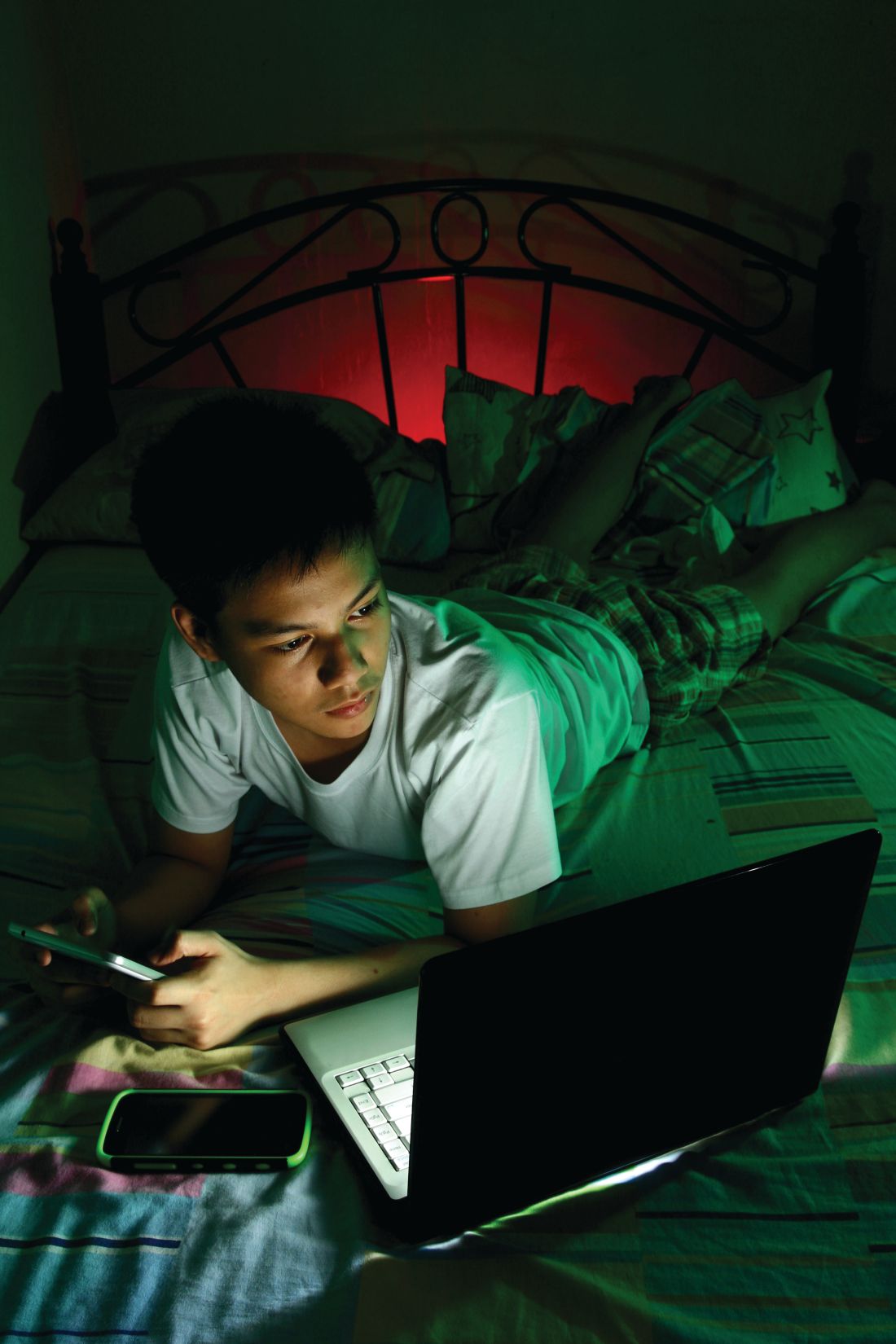

NEW ORLEANS – Social media and electronics aren’t the only barriers to a good night’s sleep for teens, according to Adiaha I. A. Spinks-Franklin, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Another half-dozen “sleep enemies” interfere with adolescents’ sleep and can contribute to insomnia or other sleep disorders, she told attendees at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Knowing what normal sleep physiology looks like in youth and understanding the most common sleep enemies and sleep-behavior problems can help you use effective interventions to help your patients get the sleep they need, she said.

Infants need the most sleep, about 12-16 hours each 24-hour period, including naps, for those aged 4-12 months. As they grow into toddlerhood and preschool age, children gradually need less: Children aged 1-2 years need 11-14 hours and children aged 3-5 years need 10-13 hours, including naps. By the time children are in school, ages 6-12, they should have dropped their naps and need 9-12 hours a night.

In fact, 75% of high school seniors get less than 8 hours of sleep a day and live with a chronic sleep debt, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Although social media use and electronics in the bedroom – TVs, computers, cell phones, and video games – can certainly contribute to inadequate sleep, a heavy academic load and extracurricular activities can be just as problematic, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Teens who work after school also may have difficulty getting enough sleep, especially if they also have to balance a heavier academic load or even one or two extracurricular activities.

Socializing with friends also can interfere with sleep, especially when get-togethers run late; drinking caffeinated drinks in the afternoon onward can make it difficult for adolescents to get the sleep they need as well. Less-modifiable contributors to too little sleep are stress and early school start times, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

The two most common sleep problems seen in teens are insomnia and delayed sleep phase syndrome. Addressing these is important because the effects of chronic insufficient sleep can have far-reaching consequences. Obesity and related chronic health conditions are associated with inadequate sleep, as are poor academic performance, poor judgment, poor executive functioning, and mental health disorders like depression.

Short-term effects of insufficient sleep also can be problematic and can exacerbate existing sleep problems, such as sleeping in on the weekends to “catch up” on sleep or drinking more caffeine to try to stay awake during the day. Increased caffeine intake can interfere with non-REM deep sleep, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said, and therefore reduce the quality of sleep even if the person gets the total hours they need.

Insomnia in adolescents

Insomnia can refer to difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, sleeping for long enough, or getting enough sleep in one period of time even when the opportunity is there. Some people may have no trouble falling asleep, but they wake up too early – before they have had gotten the sleep they need – and cannot return to sleep.

To be insomnia, the problem must occur “despite having enough time available for sleep,” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. “Patient who restrict the amount of time for sleep due to work or social commitments may have trouble sleeping and daytime sleepiness but do not have insomnia.”

Daytime impairment also is part of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s definition of insomnia. The rare teen who doesn’t need as much sleep as average and functions without difficulty during the day does not necessarily have insomnia.

But the impairment may not necessarily just be fatigue or sleepiness. In fact, many of the symptoms are the same as those seen with ADHD.

Daytime consequences of insomnia can include the following:

- Depression, feeling sad or “blue,” or emotional hypersensitivity.

- Mood swings, crankiness, or irritability.

- Difficulty concentrating or paying attention, poor memory, mind wandering, or even inability to sit still.

- Job or school problems, such as not being able to finish homework, not finishing tasks they start, or forgetfulness.

- Difficulty in social situations, such as discomfort with others or problems with friends.

- Daytime sleepiness, even when unable to actually take a nap.

- Behavioral problems, such as hyperactivity, impulsivity, or aggression.

- Frequent mistakes, especially at work, at school, or while driving (often “errors of omission,” such as not seeing a street sign or not hearing an instruction).

- Lower levels of motivation or initiative, feeling less energetic.

- Excessive worry about sleep.

Evaluation of insomnia can be framed with “the three-factor model,” which includes predisposing factors, precipitating factors, and perpetuating factors.

Predisposing factors – those that indicate a person already may be at risk for insomnia – include potential genetic influences as well as their typical response to stress. “Do they sleep more or less?” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Even teens predisposed to insomnia may not develop it, however, without a precipitating trigger.

These triggers could include stress, anxiety, poor initial sleep hygiene that becomes a pattern, dietary intake or behaviors (such as drinking caffeine or eating too much or too late in the evening), changes to their schedule, or side effects of medications.

Once insomnia begins, various factors can then perpetuate the cycle, including some of those that triggered it, such as anxiety or a school or work schedule. Sometimes it can be difficult to pinpoint the factor prolonging insomnia, such as the unconscious reward of going to work or school late with few or no consequences.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome

Delayed sleep phase syndrome occurs when someone has a delayed onset of melatonin secretion that pushes back the time when they can fall asleep. Melatonin is the neurotransmitter produced by the pineal gland that signals the start of nighttime. Although it has a hereditary component, delayed sleep phase syndrome also can result from a pattern of poor sleep onset and sleeping in on the weekends.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin described the typical cycle: A teen doesn’t go to sleep until after midnight and then wants to sleep in later in the morning. Because they have to wake up early for school, they sleep in on the weekends to try to regain the sleep they lost. Sleeping in pushes their circadian rhythm even later, perpetuating the problem.

Interventions for sleep disorders

The recommended treatment for insomnia is cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia, for which strong evidence exists. Before seeking cognitive-behavior therapy, however, families can work to improve sleep hygiene and reduce stimuli that contribute to insomnia.

Teens should avoid screens for at least 1 hour before bedtime and avoid caffeine and exercise for at least 4 hours before going to bed. They also need to develop a schedule with a consistent bedtime and wake-up time, including on the weekends. They should avoid sleeping in on the weekends or taking naps during the day, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome is more resistant to treatment and has a high recurrence rate, she said, and it requires commitment from the parent and their child to address it successfully. Teens with this condition also can start with sleep hygiene practices: a consistent wake-up time that they maintain on the weekends and no daytime naps. Phototherapy in the morning can be added to hopefully induce an earlier onset of melatonin release in the evening.

The next step is making changes to the youth’s schedule, particularly evening and/or weekend activities. They can try to gradually advance their biological clock by changing their sleep schedule.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin also briefly addressed the use of over-the-counter melatonin supplements for treating sleep problems. Melatonin can be effective for treating insomnia by improving sleep onset and sleep quality, particularly in children and teens with autism spectrum disorder or ADHD.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin had no disclosures, and her presentation used no outside funding.

NEW ORLEANS – Social media and electronics aren’t the only barriers to a good night’s sleep for teens, according to Adiaha I. A. Spinks-Franklin, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Another half-dozen “sleep enemies” interfere with adolescents’ sleep and can contribute to insomnia or other sleep disorders, she told attendees at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Knowing what normal sleep physiology looks like in youth and understanding the most common sleep enemies and sleep-behavior problems can help you use effective interventions to help your patients get the sleep they need, she said.

Infants need the most sleep, about 12-16 hours each 24-hour period, including naps, for those aged 4-12 months. As they grow into toddlerhood and preschool age, children gradually need less: Children aged 1-2 years need 11-14 hours and children aged 3-5 years need 10-13 hours, including naps. By the time children are in school, ages 6-12, they should have dropped their naps and need 9-12 hours a night.

In fact, 75% of high school seniors get less than 8 hours of sleep a day and live with a chronic sleep debt, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Although social media use and electronics in the bedroom – TVs, computers, cell phones, and video games – can certainly contribute to inadequate sleep, a heavy academic load and extracurricular activities can be just as problematic, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Teens who work after school also may have difficulty getting enough sleep, especially if they also have to balance a heavier academic load or even one or two extracurricular activities.

Socializing with friends also can interfere with sleep, especially when get-togethers run late; drinking caffeinated drinks in the afternoon onward can make it difficult for adolescents to get the sleep they need as well. Less-modifiable contributors to too little sleep are stress and early school start times, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

The two most common sleep problems seen in teens are insomnia and delayed sleep phase syndrome. Addressing these is important because the effects of chronic insufficient sleep can have far-reaching consequences. Obesity and related chronic health conditions are associated with inadequate sleep, as are poor academic performance, poor judgment, poor executive functioning, and mental health disorders like depression.

Short-term effects of insufficient sleep also can be problematic and can exacerbate existing sleep problems, such as sleeping in on the weekends to “catch up” on sleep or drinking more caffeine to try to stay awake during the day. Increased caffeine intake can interfere with non-REM deep sleep, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said, and therefore reduce the quality of sleep even if the person gets the total hours they need.

Insomnia in adolescents

Insomnia can refer to difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, sleeping for long enough, or getting enough sleep in one period of time even when the opportunity is there. Some people may have no trouble falling asleep, but they wake up too early – before they have had gotten the sleep they need – and cannot return to sleep.

To be insomnia, the problem must occur “despite having enough time available for sleep,” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. “Patient who restrict the amount of time for sleep due to work or social commitments may have trouble sleeping and daytime sleepiness but do not have insomnia.”

Daytime impairment also is part of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s definition of insomnia. The rare teen who doesn’t need as much sleep as average and functions without difficulty during the day does not necessarily have insomnia.

But the impairment may not necessarily just be fatigue or sleepiness. In fact, many of the symptoms are the same as those seen with ADHD.

Daytime consequences of insomnia can include the following:

- Depression, feeling sad or “blue,” or emotional hypersensitivity.

- Mood swings, crankiness, or irritability.

- Difficulty concentrating or paying attention, poor memory, mind wandering, or even inability to sit still.

- Job or school problems, such as not being able to finish homework, not finishing tasks they start, or forgetfulness.

- Difficulty in social situations, such as discomfort with others or problems with friends.

- Daytime sleepiness, even when unable to actually take a nap.

- Behavioral problems, such as hyperactivity, impulsivity, or aggression.

- Frequent mistakes, especially at work, at school, or while driving (often “errors of omission,” such as not seeing a street sign or not hearing an instruction).

- Lower levels of motivation or initiative, feeling less energetic.

- Excessive worry about sleep.

Evaluation of insomnia can be framed with “the three-factor model,” which includes predisposing factors, precipitating factors, and perpetuating factors.

Predisposing factors – those that indicate a person already may be at risk for insomnia – include potential genetic influences as well as their typical response to stress. “Do they sleep more or less?” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Even teens predisposed to insomnia may not develop it, however, without a precipitating trigger.

These triggers could include stress, anxiety, poor initial sleep hygiene that becomes a pattern, dietary intake or behaviors (such as drinking caffeine or eating too much or too late in the evening), changes to their schedule, or side effects of medications.

Once insomnia begins, various factors can then perpetuate the cycle, including some of those that triggered it, such as anxiety or a school or work schedule. Sometimes it can be difficult to pinpoint the factor prolonging insomnia, such as the unconscious reward of going to work or school late with few or no consequences.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome

Delayed sleep phase syndrome occurs when someone has a delayed onset of melatonin secretion that pushes back the time when they can fall asleep. Melatonin is the neurotransmitter produced by the pineal gland that signals the start of nighttime. Although it has a hereditary component, delayed sleep phase syndrome also can result from a pattern of poor sleep onset and sleeping in on the weekends.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin described the typical cycle: A teen doesn’t go to sleep until after midnight and then wants to sleep in later in the morning. Because they have to wake up early for school, they sleep in on the weekends to try to regain the sleep they lost. Sleeping in pushes their circadian rhythm even later, perpetuating the problem.

Interventions for sleep disorders

The recommended treatment for insomnia is cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia, for which strong evidence exists. Before seeking cognitive-behavior therapy, however, families can work to improve sleep hygiene and reduce stimuli that contribute to insomnia.

Teens should avoid screens for at least 1 hour before bedtime and avoid caffeine and exercise for at least 4 hours before going to bed. They also need to develop a schedule with a consistent bedtime and wake-up time, including on the weekends. They should avoid sleeping in on the weekends or taking naps during the day, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome is more resistant to treatment and has a high recurrence rate, she said, and it requires commitment from the parent and their child to address it successfully. Teens with this condition also can start with sleep hygiene practices: a consistent wake-up time that they maintain on the weekends and no daytime naps. Phototherapy in the morning can be added to hopefully induce an earlier onset of melatonin release in the evening.

The next step is making changes to the youth’s schedule, particularly evening and/or weekend activities. They can try to gradually advance their biological clock by changing their sleep schedule.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin also briefly addressed the use of over-the-counter melatonin supplements for treating sleep problems. Melatonin can be effective for treating insomnia by improving sleep onset and sleep quality, particularly in children and teens with autism spectrum disorder or ADHD.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin had no disclosures, and her presentation used no outside funding.

NEW ORLEANS – Social media and electronics aren’t the only barriers to a good night’s sleep for teens, according to Adiaha I. A. Spinks-Franklin, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Another half-dozen “sleep enemies” interfere with adolescents’ sleep and can contribute to insomnia or other sleep disorders, she told attendees at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Knowing what normal sleep physiology looks like in youth and understanding the most common sleep enemies and sleep-behavior problems can help you use effective interventions to help your patients get the sleep they need, she said.

Infants need the most sleep, about 12-16 hours each 24-hour period, including naps, for those aged 4-12 months. As they grow into toddlerhood and preschool age, children gradually need less: Children aged 1-2 years need 11-14 hours and children aged 3-5 years need 10-13 hours, including naps. By the time children are in school, ages 6-12, they should have dropped their naps and need 9-12 hours a night.

In fact, 75% of high school seniors get less than 8 hours of sleep a day and live with a chronic sleep debt, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Although social media use and electronics in the bedroom – TVs, computers, cell phones, and video games – can certainly contribute to inadequate sleep, a heavy academic load and extracurricular activities can be just as problematic, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Teens who work after school also may have difficulty getting enough sleep, especially if they also have to balance a heavier academic load or even one or two extracurricular activities.

Socializing with friends also can interfere with sleep, especially when get-togethers run late; drinking caffeinated drinks in the afternoon onward can make it difficult for adolescents to get the sleep they need as well. Less-modifiable contributors to too little sleep are stress and early school start times, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

The two most common sleep problems seen in teens are insomnia and delayed sleep phase syndrome. Addressing these is important because the effects of chronic insufficient sleep can have far-reaching consequences. Obesity and related chronic health conditions are associated with inadequate sleep, as are poor academic performance, poor judgment, poor executive functioning, and mental health disorders like depression.

Short-term effects of insufficient sleep also can be problematic and can exacerbate existing sleep problems, such as sleeping in on the weekends to “catch up” on sleep or drinking more caffeine to try to stay awake during the day. Increased caffeine intake can interfere with non-REM deep sleep, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said, and therefore reduce the quality of sleep even if the person gets the total hours they need.

Insomnia in adolescents

Insomnia can refer to difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, sleeping for long enough, or getting enough sleep in one period of time even when the opportunity is there. Some people may have no trouble falling asleep, but they wake up too early – before they have had gotten the sleep they need – and cannot return to sleep.

To be insomnia, the problem must occur “despite having enough time available for sleep,” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. “Patient who restrict the amount of time for sleep due to work or social commitments may have trouble sleeping and daytime sleepiness but do not have insomnia.”

Daytime impairment also is part of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s definition of insomnia. The rare teen who doesn’t need as much sleep as average and functions without difficulty during the day does not necessarily have insomnia.

But the impairment may not necessarily just be fatigue or sleepiness. In fact, many of the symptoms are the same as those seen with ADHD.

Daytime consequences of insomnia can include the following:

- Depression, feeling sad or “blue,” or emotional hypersensitivity.

- Mood swings, crankiness, or irritability.

- Difficulty concentrating or paying attention, poor memory, mind wandering, or even inability to sit still.

- Job or school problems, such as not being able to finish homework, not finishing tasks they start, or forgetfulness.

- Difficulty in social situations, such as discomfort with others or problems with friends.

- Daytime sleepiness, even when unable to actually take a nap.

- Behavioral problems, such as hyperactivity, impulsivity, or aggression.

- Frequent mistakes, especially at work, at school, or while driving (often “errors of omission,” such as not seeing a street sign or not hearing an instruction).

- Lower levels of motivation or initiative, feeling less energetic.

- Excessive worry about sleep.

Evaluation of insomnia can be framed with “the three-factor model,” which includes predisposing factors, precipitating factors, and perpetuating factors.

Predisposing factors – those that indicate a person already may be at risk for insomnia – include potential genetic influences as well as their typical response to stress. “Do they sleep more or less?” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Even teens predisposed to insomnia may not develop it, however, without a precipitating trigger.

These triggers could include stress, anxiety, poor initial sleep hygiene that becomes a pattern, dietary intake or behaviors (such as drinking caffeine or eating too much or too late in the evening), changes to their schedule, or side effects of medications.

Once insomnia begins, various factors can then perpetuate the cycle, including some of those that triggered it, such as anxiety or a school or work schedule. Sometimes it can be difficult to pinpoint the factor prolonging insomnia, such as the unconscious reward of going to work or school late with few or no consequences.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome

Delayed sleep phase syndrome occurs when someone has a delayed onset of melatonin secretion that pushes back the time when they can fall asleep. Melatonin is the neurotransmitter produced by the pineal gland that signals the start of nighttime. Although it has a hereditary component, delayed sleep phase syndrome also can result from a pattern of poor sleep onset and sleeping in on the weekends.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin described the typical cycle: A teen doesn’t go to sleep until after midnight and then wants to sleep in later in the morning. Because they have to wake up early for school, they sleep in on the weekends to try to regain the sleep they lost. Sleeping in pushes their circadian rhythm even later, perpetuating the problem.

Interventions for sleep disorders

The recommended treatment for insomnia is cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia, for which strong evidence exists. Before seeking cognitive-behavior therapy, however, families can work to improve sleep hygiene and reduce stimuli that contribute to insomnia.

Teens should avoid screens for at least 1 hour before bedtime and avoid caffeine and exercise for at least 4 hours before going to bed. They also need to develop a schedule with a consistent bedtime and wake-up time, including on the weekends. They should avoid sleeping in on the weekends or taking naps during the day, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome is more resistant to treatment and has a high recurrence rate, she said, and it requires commitment from the parent and their child to address it successfully. Teens with this condition also can start with sleep hygiene practices: a consistent wake-up time that they maintain on the weekends and no daytime naps. Phototherapy in the morning can be added to hopefully induce an earlier onset of melatonin release in the evening.

The next step is making changes to the youth’s schedule, particularly evening and/or weekend activities. They can try to gradually advance their biological clock by changing their sleep schedule.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin also briefly addressed the use of over-the-counter melatonin supplements for treating sleep problems. Melatonin can be effective for treating insomnia by improving sleep onset and sleep quality, particularly in children and teens with autism spectrum disorder or ADHD.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin had no disclosures, and her presentation used no outside funding.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 19

Pediatricians uniquely qualified to treat adolescents with opioid use disorder

NEW ORLEANS –

“One of the real benefits of treatment in primary care is that it removes the stigma so that these patients aren’t isolated into addiction clinics; they’re being treated by providers that they know well and that their family knows well,” Dr. Reynolds, a pediatrician who practices in Wareham, Mass., said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “That feels a lot better to them, and I think it makes a statement in the community that these people don’t need to be isolated. Anything we can do to reduce the stigma of opioid use disorder is important. We in primary care are well suited to manage chronic disease over the continuum.”

In 2016, the AAP released a policy statement advocating for pediatricians to consider providing medication-assisted treatment to patients with OUD (Pediatrics. 2016;138[3]e20161893). The statement cited results from a nationally representative sample of 345 addiction treatment programs serving adolescents and adults. It found that fewer than 50% of those programs used medication-assisted treatment (J Addict Med. 2011;5[1]:21-7). “When they looked at patients who actually had opioid dependence, the numbers were even lower,” said Dr. Reynolds, who was not involved with the study. “In fact, 34% of opioid-dependent patients received medication-assisted treatment. When they stratified it by age, the younger you were, the less likely you were to be treated. Only 11.5% of youth under 18 are actually being treated. We know that youth with opioid use disorders have very bad health outcomes over their lifetime. The fact that such few patients receive what is considered to be a gold-standard treatment is really alarming.”

Dr. Reynolds acknowledged that many perceived barriers exist to providing treatment of OUD in pediatric primary care, including the fact that patients with addiction are not easy to treat. “They can be manipulative and can make you feel both sad for them and angry at them within the same visit,” he said. “They also have complex needs. For many of these patients, it’s not just that they use opiates; they have medical problems and psychological diagnoses, and oftentimes they have social issues such as being in foster care. They also may have issues with their parents, employer, or their school, so there are many needs that need to be juggled. That can be overwhelming.”

However, he said that such patients “are actually in our wheelhouse, because as primary care physicians we’re used to coordinating care. These are the perfect patients to have a medical home. We manage chronic disease over the continuum of care. This is a chronic disease, and we have to help patients.”

Another perceived barrier for treating adolescents with OUD relates to reimbursement. While most patients with OUD have insurance, Dr. Reynolds finds that the requirement for prior authorizations can result in delay of treatment and poses an unnecessary burden on care providers. “It’s an administrative task that either the physician or the office staff has to take care of,” he said. “Interestingly, reimbursement ranks as a low concern in studies of buprenorphine providers. That tells me that this is not a major hurdle.”

Pediatricians also cite a lack of knowledge as a reason they’re leery of providing OUD treatment in their office. “They wonder: ‘How do I do this? What’s the right way to do it? Are there best practices?’ ” Dr. Reynolds said. “There’s a feeling that it must be dangerous, the idea that if I don’t do it right I’m going to hurt somebody. The reality is, buprenorphine is no more dangerous than any of the other opiates. Technically, because it’s a partial agonist, it’s probably less dangerous than some of the opiates that we prescribe. It’s no more dangerous than prescribing amitriptyline for chronic pain.”

One key resource, the Providers Clinical Support System (www.pcssnow.org), provides resources for clinicians and family members, education and training, and access to mentoring. Another resource, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (www.asam.org), includes clinical practice guidelines, online courses and training on the treatment of OUD, and sample consent and opioid-withdrawal forms. Dr. Reynolds characterized learning how to treat patients with OUD as no different than learning step therapy for asthma. “Once you look into it, you realize that there’s no sort of magic behind this,” he said. “It’s something that any of us can do. Staff can be trained. There are modules to train your staff into the protocols. Learn the knowledge and put it into action. Have the confidence and the knowledge.”

The Drug Addiction and Treatment Act of 2000 set up the waiver process by which physicians can obtain a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Agency after completing an 8-hour CME course on substance abuse disorder and buprenorphine prescribing. To receive a waiver to practice opioid dependency treatment with approved buprenorphine medications, a clinician must notify the SAMHSA Center for Substance Abuse Treatment of their intent to practice this form of medication-assisted treatment.

Dr. Reynolds acknowledged that not every practice is equipped to provide psychosocial support for complex patients with OUD. “When I first started this in 2017, I wanted to make sure that my patients were in some form of counseling,” he said. “However, the medical literature shows that you can treat OUD without counseling, and some of those patients will be fine, too. There have been reports that just going to Narcotics Anonymous meetings weekly has been shown to improve the effectiveness of medication-assisted treatment.”

For clinicians concerned about having backup when they face challenging cases, data shows that having more than one waivered provider in a practice is associated with completing waiver training. “This makes sense,” Dr. Reynolds said. “We like to be able to discuss our cases with colleagues, but a lot of us don’t want to be on call 365 days a year for our patients. Shared responsibility makes it easier. Access to specialty telemedicine consult has also been identified as a facilitator to physicians prescribing medical-assisted therapy.”

He concluded his presentation by noting that increasing numbers of OUD patients are initiating buprenorphine treatment in the ED. “That takes advantage of the fact that most of these patients present to the emergency room after receiving Narcan for an overdose,” Dr. Reynolds said. “In the emergency room, they’re counseled and instructed on how to start buprenorphine, they’re given the first dose, and they’re told to go home and avoid using any other opiates for 24 hours, start the buprenorphine, and follow up with their primary care doctor or an addiction medicine specialist in 3 days. In my community, this is what our local emergency department is doing for adult patients, except they’re not referring back to primary care. They’re referring to a hospital-based addiction medicine specialist. This is a way to increase access and get people started on buprenorphine treatment.”

Dr. Reynolds reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS –

“One of the real benefits of treatment in primary care is that it removes the stigma so that these patients aren’t isolated into addiction clinics; they’re being treated by providers that they know well and that their family knows well,” Dr. Reynolds, a pediatrician who practices in Wareham, Mass., said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “That feels a lot better to them, and I think it makes a statement in the community that these people don’t need to be isolated. Anything we can do to reduce the stigma of opioid use disorder is important. We in primary care are well suited to manage chronic disease over the continuum.”

In 2016, the AAP released a policy statement advocating for pediatricians to consider providing medication-assisted treatment to patients with OUD (Pediatrics. 2016;138[3]e20161893). The statement cited results from a nationally representative sample of 345 addiction treatment programs serving adolescents and adults. It found that fewer than 50% of those programs used medication-assisted treatment (J Addict Med. 2011;5[1]:21-7). “When they looked at patients who actually had opioid dependence, the numbers were even lower,” said Dr. Reynolds, who was not involved with the study. “In fact, 34% of opioid-dependent patients received medication-assisted treatment. When they stratified it by age, the younger you were, the less likely you were to be treated. Only 11.5% of youth under 18 are actually being treated. We know that youth with opioid use disorders have very bad health outcomes over their lifetime. The fact that such few patients receive what is considered to be a gold-standard treatment is really alarming.”

Dr. Reynolds acknowledged that many perceived barriers exist to providing treatment of OUD in pediatric primary care, including the fact that patients with addiction are not easy to treat. “They can be manipulative and can make you feel both sad for them and angry at them within the same visit,” he said. “They also have complex needs. For many of these patients, it’s not just that they use opiates; they have medical problems and psychological diagnoses, and oftentimes they have social issues such as being in foster care. They also may have issues with their parents, employer, or their school, so there are many needs that need to be juggled. That can be overwhelming.”

However, he said that such patients “are actually in our wheelhouse, because as primary care physicians we’re used to coordinating care. These are the perfect patients to have a medical home. We manage chronic disease over the continuum of care. This is a chronic disease, and we have to help patients.”

Another perceived barrier for treating adolescents with OUD relates to reimbursement. While most patients with OUD have insurance, Dr. Reynolds finds that the requirement for prior authorizations can result in delay of treatment and poses an unnecessary burden on care providers. “It’s an administrative task that either the physician or the office staff has to take care of,” he said. “Interestingly, reimbursement ranks as a low concern in studies of buprenorphine providers. That tells me that this is not a major hurdle.”

Pediatricians also cite a lack of knowledge as a reason they’re leery of providing OUD treatment in their office. “They wonder: ‘How do I do this? What’s the right way to do it? Are there best practices?’ ” Dr. Reynolds said. “There’s a feeling that it must be dangerous, the idea that if I don’t do it right I’m going to hurt somebody. The reality is, buprenorphine is no more dangerous than any of the other opiates. Technically, because it’s a partial agonist, it’s probably less dangerous than some of the opiates that we prescribe. It’s no more dangerous than prescribing amitriptyline for chronic pain.”

One key resource, the Providers Clinical Support System (www.pcssnow.org), provides resources for clinicians and family members, education and training, and access to mentoring. Another resource, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (www.asam.org), includes clinical practice guidelines, online courses and training on the treatment of OUD, and sample consent and opioid-withdrawal forms. Dr. Reynolds characterized learning how to treat patients with OUD as no different than learning step therapy for asthma. “Once you look into it, you realize that there’s no sort of magic behind this,” he said. “It’s something that any of us can do. Staff can be trained. There are modules to train your staff into the protocols. Learn the knowledge and put it into action. Have the confidence and the knowledge.”

The Drug Addiction and Treatment Act of 2000 set up the waiver process by which physicians can obtain a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Agency after completing an 8-hour CME course on substance abuse disorder and buprenorphine prescribing. To receive a waiver to practice opioid dependency treatment with approved buprenorphine medications, a clinician must notify the SAMHSA Center for Substance Abuse Treatment of their intent to practice this form of medication-assisted treatment.

Dr. Reynolds acknowledged that not every practice is equipped to provide psychosocial support for complex patients with OUD. “When I first started this in 2017, I wanted to make sure that my patients were in some form of counseling,” he said. “However, the medical literature shows that you can treat OUD without counseling, and some of those patients will be fine, too. There have been reports that just going to Narcotics Anonymous meetings weekly has been shown to improve the effectiveness of medication-assisted treatment.”

For clinicians concerned about having backup when they face challenging cases, data shows that having more than one waivered provider in a practice is associated with completing waiver training. “This makes sense,” Dr. Reynolds said. “We like to be able to discuss our cases with colleagues, but a lot of us don’t want to be on call 365 days a year for our patients. Shared responsibility makes it easier. Access to specialty telemedicine consult has also been identified as a facilitator to physicians prescribing medical-assisted therapy.”

He concluded his presentation by noting that increasing numbers of OUD patients are initiating buprenorphine treatment in the ED. “That takes advantage of the fact that most of these patients present to the emergency room after receiving Narcan for an overdose,” Dr. Reynolds said. “In the emergency room, they’re counseled and instructed on how to start buprenorphine, they’re given the first dose, and they’re told to go home and avoid using any other opiates for 24 hours, start the buprenorphine, and follow up with their primary care doctor or an addiction medicine specialist in 3 days. In my community, this is what our local emergency department is doing for adult patients, except they’re not referring back to primary care. They’re referring to a hospital-based addiction medicine specialist. This is a way to increase access and get people started on buprenorphine treatment.”

Dr. Reynolds reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS –

“One of the real benefits of treatment in primary care is that it removes the stigma so that these patients aren’t isolated into addiction clinics; they’re being treated by providers that they know well and that their family knows well,” Dr. Reynolds, a pediatrician who practices in Wareham, Mass., said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “That feels a lot better to them, and I think it makes a statement in the community that these people don’t need to be isolated. Anything we can do to reduce the stigma of opioid use disorder is important. We in primary care are well suited to manage chronic disease over the continuum.”

In 2016, the AAP released a policy statement advocating for pediatricians to consider providing medication-assisted treatment to patients with OUD (Pediatrics. 2016;138[3]e20161893). The statement cited results from a nationally representative sample of 345 addiction treatment programs serving adolescents and adults. It found that fewer than 50% of those programs used medication-assisted treatment (J Addict Med. 2011;5[1]:21-7). “When they looked at patients who actually had opioid dependence, the numbers were even lower,” said Dr. Reynolds, who was not involved with the study. “In fact, 34% of opioid-dependent patients received medication-assisted treatment. When they stratified it by age, the younger you were, the less likely you were to be treated. Only 11.5% of youth under 18 are actually being treated. We know that youth with opioid use disorders have very bad health outcomes over their lifetime. The fact that such few patients receive what is considered to be a gold-standard treatment is really alarming.”

Dr. Reynolds acknowledged that many perceived barriers exist to providing treatment of OUD in pediatric primary care, including the fact that patients with addiction are not easy to treat. “They can be manipulative and can make you feel both sad for them and angry at them within the same visit,” he said. “They also have complex needs. For many of these patients, it’s not just that they use opiates; they have medical problems and psychological diagnoses, and oftentimes they have social issues such as being in foster care. They also may have issues with their parents, employer, or their school, so there are many needs that need to be juggled. That can be overwhelming.”

However, he said that such patients “are actually in our wheelhouse, because as primary care physicians we’re used to coordinating care. These are the perfect patients to have a medical home. We manage chronic disease over the continuum of care. This is a chronic disease, and we have to help patients.”

Another perceived barrier for treating adolescents with OUD relates to reimbursement. While most patients with OUD have insurance, Dr. Reynolds finds that the requirement for prior authorizations can result in delay of treatment and poses an unnecessary burden on care providers. “It’s an administrative task that either the physician or the office staff has to take care of,” he said. “Interestingly, reimbursement ranks as a low concern in studies of buprenorphine providers. That tells me that this is not a major hurdle.”

Pediatricians also cite a lack of knowledge as a reason they’re leery of providing OUD treatment in their office. “They wonder: ‘How do I do this? What’s the right way to do it? Are there best practices?’ ” Dr. Reynolds said. “There’s a feeling that it must be dangerous, the idea that if I don’t do it right I’m going to hurt somebody. The reality is, buprenorphine is no more dangerous than any of the other opiates. Technically, because it’s a partial agonist, it’s probably less dangerous than some of the opiates that we prescribe. It’s no more dangerous than prescribing amitriptyline for chronic pain.”

One key resource, the Providers Clinical Support System (www.pcssnow.org), provides resources for clinicians and family members, education and training, and access to mentoring. Another resource, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (www.asam.org), includes clinical practice guidelines, online courses and training on the treatment of OUD, and sample consent and opioid-withdrawal forms. Dr. Reynolds characterized learning how to treat patients with OUD as no different than learning step therapy for asthma. “Once you look into it, you realize that there’s no sort of magic behind this,” he said. “It’s something that any of us can do. Staff can be trained. There are modules to train your staff into the protocols. Learn the knowledge and put it into action. Have the confidence and the knowledge.”

The Drug Addiction and Treatment Act of 2000 set up the waiver process by which physicians can obtain a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Agency after completing an 8-hour CME course on substance abuse disorder and buprenorphine prescribing. To receive a waiver to practice opioid dependency treatment with approved buprenorphine medications, a clinician must notify the SAMHSA Center for Substance Abuse Treatment of their intent to practice this form of medication-assisted treatment.

Dr. Reynolds acknowledged that not every practice is equipped to provide psychosocial support for complex patients with OUD. “When I first started this in 2017, I wanted to make sure that my patients were in some form of counseling,” he said. “However, the medical literature shows that you can treat OUD without counseling, and some of those patients will be fine, too. There have been reports that just going to Narcotics Anonymous meetings weekly has been shown to improve the effectiveness of medication-assisted treatment.”

For clinicians concerned about having backup when they face challenging cases, data shows that having more than one waivered provider in a practice is associated with completing waiver training. “This makes sense,” Dr. Reynolds said. “We like to be able to discuss our cases with colleagues, but a lot of us don’t want to be on call 365 days a year for our patients. Shared responsibility makes it easier. Access to specialty telemedicine consult has also been identified as a facilitator to physicians prescribing medical-assisted therapy.”

He concluded his presentation by noting that increasing numbers of OUD patients are initiating buprenorphine treatment in the ED. “That takes advantage of the fact that most of these patients present to the emergency room after receiving Narcan for an overdose,” Dr. Reynolds said. “In the emergency room, they’re counseled and instructed on how to start buprenorphine, they’re given the first dose, and they’re told to go home and avoid using any other opiates for 24 hours, start the buprenorphine, and follow up with their primary care doctor or an addiction medicine specialist in 3 days. In my community, this is what our local emergency department is doing for adult patients, except they’re not referring back to primary care. They’re referring to a hospital-based addiction medicine specialist. This is a way to increase access and get people started on buprenorphine treatment.”

Dr. Reynolds reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 19

Adding mental health clinicians to your practice is full of benefits

NEW ORLEANS – The way Jay Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, sees it, providing mental and behavioral health care services in your primary care pediatrics practice is a win-win for patients, parents, and clinicians.

For one thing, children with mental and behavioral issues – especially depression and anxiety – make up a good chunk of any pediatrician’s workday. Dr. Rabinowitz, clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Aurora, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It is the most costly issue in children’s health care today.”

According to “Behavioral Health Integration in Pediatric Primary Care,” a report supported by the Milbank Memorial Fund, one in five children aged 9-17 years have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder, and up to 70% of children in the juvenile justice system have a mental health disorder. The report also found that the treatment of mental health disorders accounts for the most costly childhood medical expenditure, and that between 15% and 20% of children with psychiatric disorders receive specialty care; the rest see their primary care provider. A long-term cost analysis showed significant cost savings: $1 spent on collaborative care saves $6.50 on health care costs.

More recently, the Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC) found that only 50% of adolescents with depression are diagnosed before reaching adulthood (Pediatrics. March 2018;141[3]:e20174081). As many as two out of three youth with depression are not identified by their pediatrician and do not receive any kind of care.

“Even when diagnosed, only half of these patients are treated appropriately,” said Dr. Rabinowitz, who also practices at Parker (Colo.) Pediatrics and Adolescents.

The guidelines also found that reliance on self-report depression checklists alone lead to substantial numbers of false-positive and false-negative cases. “Primary care providers will benefit from having access to ongoing consultation with mental health providers,” according to the guidelines.

“Integrative care was associated with significant decreases in depression scores, and improved response and remission rates at 12 months, compared with treatment as usual,” Dr. Rabinowitz said.

Providing mental health services in a primary care pediatrics setting also makes sense because there’s a shortage of psychiatrists and psychologists to see them, and it enables patients to get evaluated quicker. “It’s convenient, and it reduces stigma,” he added. “It’s a familiar setting, a familiar provider, and they’re more likely to initiate counseling. Nationwide, 50% of patients who are referred for mental health do not make their initial appointment. Think about that. If you had diabetics in your practice and only 50% would go to the endocrinologist, what would you think?”

How Dr. Rabinowitz and his partners got started

Dr. Rabinowitz and his colleagues created an integrated care model in 2008 by adding a psychologist to their practice, but before doing that, they asked parents of children with mental and behavioral health issues what type of insurance they had. Then they obtained a referral list from the family’s insurer and hoped for the best. “Sometimes I referred to someone I may not have heard of,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “Usually I did not get follow-up reports, or even know for sure if the patient ever went.”

Today, Parker Pediatrics and Adolescents employs three doctoral-level psychologists: one full-time, one three-quarter time, and one half-time, as well as one master’s-level therapist who works half-time.

“On any given day, we have at least two counselors in our office,” said Lindsey Einhorn, PhD, a licensed clinical psychologist who joined the practice in 2011. She and her colleagues care for children and teens with ADHD, depression, anxiety, behavioral and adjustment disorders, drug counseling, behavioral addictions, social struggles such as bullying, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), loss, hair or eyelash pulling, mood dysregulation, and sibling conflict. They refer for educational testing, comprehensive psychological evaluations, difficult divorce cases, play therapy, complex cases requiring more than 20 sessions, and children of staff employed by the practice.

The practice features a separate waiting room for psychology patients and front office staff dedicated to managing their schedules. “For anyone who’s trying to make a psychology appointment but can’t be seen in an efficient manner or wants a different day or time, we keep an ongoing move-up list,” Dr. Einhorn said. “If a family calls to cancel an appointment, the front desk person who makes that cancellation will fill out a slip and give it to one of our psychology schedulers. That person will create a move-up list and start filling that appointment. If there’s a cancellation, it’s rare that it goes unfilled.”

Key forms for parents to complete include informed consent, a notice of privacy practices, a late cancel/no show policy, an initial intake agreement, and a summary of parent concerns.

Patient and clinician reaction

According to results from a recent survey of parents whose children were seen by a psychologist at Parker Pediatrics and Adolescents, 89% said it was important for their children to receive mental health services in the same location as their medical care, and 96% were satisfied with the services provided. In addition, 93% said that the experience benefited their child, 72% were satisfied with appointment times, and 55% expressed interest in virtual visits via telemedicine. Meanwhile, a survey of parents whose children have not been seen by a psychologist at the practice found that 65% knew a psychologist was on staff, and only 9% said that there were barriers to their child seeing a psychologist there.

Clinicians themselves benefit from having mental health specialists on site for referrals. “It enables you to be more efficient, and it saves time,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “There’s knowledge and confidence gained, and it improves satisfaction because physicians don’t have to stay at the office later filling out referral forms. It meets the needs of your patients and their families, it attracts new patients, and you may be able to make some income on this.”

How to get started

Dr. Rabinowitz recommended that, once clinicians at a pediatric practice commit to expanding their services to include mental and behavioral health care, they should hold a corporate/partner meeting, assign responsibilities, and establish a timeline for implementation. “This is all very important,” he said. “Then you have to talk about what kind of arrangement you want to have. You could employ someone to join your practice, hire an independent contractor, establish a space share agreement, or have an out-of-office arrangement.”

For many years, clinicians at Parker Pediatrics and Adolescents had a psychologist perform ADHD evaluations on a consultative basis. “Then, as we saw a need for mental health services about a decade ago, we hired a part-time psychologist who did testing as well as counseling,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “But that psychologist got very busy, so we hired a full-time psychologist. We continued to hire additional psychologists as need increased.”

Reimbursement issues

Numerous reimbursement barriers to providing mental health services in pediatric primary care exist, he noted, including a lack of payment if mental health codes are used, a lack of “incident to” payments in some areas of the country, existing reimbursement levels, and the fact that same-day billing of physical and mental health often is not allowed. “However, we have found that if we give flu shots during their mental health visit, [insurers] will cover the flu shot,” he said. “Reimbursement for screening is sometimes not covered very well.”

One reimbursement option is the fee-for-service/concierge model, “but that’s not an economic option for many,” he said. “You can’t see Medicaid patients in that model.” Joining a mental health networks is feasible, “but there is poor reimbursement,” he said. “It also creates another layer of administration.”

He recommends financial integration, “but you need to research your options because a lot of it is state dependent.” Other options include grants, insurance contracts, and seeking permission from Medicaid.

Mental health CPT codes that mental health clinicians at the practice commonly use include bill by time (CPT code 99214/15); psychotherapy session that lasts 16-37 minutes (CPT code 90832); psychotherapy session that lasts 38-52 minutes (CPT code 90834); and psychotherapy session that lasts more than 53 minutes (CPT code 90837). Clinicians also can bill by interactive complexity (CPT code 90785) and psychotherapy for crisis (CPT code 90839).

Dr. Rabinowitz and Dr. Einhorn reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – The way Jay Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, sees it, providing mental and behavioral health care services in your primary care pediatrics practice is a win-win for patients, parents, and clinicians.

For one thing, children with mental and behavioral issues – especially depression and anxiety – make up a good chunk of any pediatrician’s workday. Dr. Rabinowitz, clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Aurora, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It is the most costly issue in children’s health care today.”

According to “Behavioral Health Integration in Pediatric Primary Care,” a report supported by the Milbank Memorial Fund, one in five children aged 9-17 years have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder, and up to 70% of children in the juvenile justice system have a mental health disorder. The report also found that the treatment of mental health disorders accounts for the most costly childhood medical expenditure, and that between 15% and 20% of children with psychiatric disorders receive specialty care; the rest see their primary care provider. A long-term cost analysis showed significant cost savings: $1 spent on collaborative care saves $6.50 on health care costs.

More recently, the Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC) found that only 50% of adolescents with depression are diagnosed before reaching adulthood (Pediatrics. March 2018;141[3]:e20174081). As many as two out of three youth with depression are not identified by their pediatrician and do not receive any kind of care.

“Even when diagnosed, only half of these patients are treated appropriately,” said Dr. Rabinowitz, who also practices at Parker (Colo.) Pediatrics and Adolescents.

The guidelines also found that reliance on self-report depression checklists alone lead to substantial numbers of false-positive and false-negative cases. “Primary care providers will benefit from having access to ongoing consultation with mental health providers,” according to the guidelines.

“Integrative care was associated with significant decreases in depression scores, and improved response and remission rates at 12 months, compared with treatment as usual,” Dr. Rabinowitz said.

Providing mental health services in a primary care pediatrics setting also makes sense because there’s a shortage of psychiatrists and psychologists to see them, and it enables patients to get evaluated quicker. “It’s convenient, and it reduces stigma,” he added. “It’s a familiar setting, a familiar provider, and they’re more likely to initiate counseling. Nationwide, 50% of patients who are referred for mental health do not make their initial appointment. Think about that. If you had diabetics in your practice and only 50% would go to the endocrinologist, what would you think?”

How Dr. Rabinowitz and his partners got started

Dr. Rabinowitz and his colleagues created an integrated care model in 2008 by adding a psychologist to their practice, but before doing that, they asked parents of children with mental and behavioral health issues what type of insurance they had. Then they obtained a referral list from the family’s insurer and hoped for the best. “Sometimes I referred to someone I may not have heard of,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “Usually I did not get follow-up reports, or even know for sure if the patient ever went.”

Today, Parker Pediatrics and Adolescents employs three doctoral-level psychologists: one full-time, one three-quarter time, and one half-time, as well as one master’s-level therapist who works half-time.

“On any given day, we have at least two counselors in our office,” said Lindsey Einhorn, PhD, a licensed clinical psychologist who joined the practice in 2011. She and her colleagues care for children and teens with ADHD, depression, anxiety, behavioral and adjustment disorders, drug counseling, behavioral addictions, social struggles such as bullying, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), loss, hair or eyelash pulling, mood dysregulation, and sibling conflict. They refer for educational testing, comprehensive psychological evaluations, difficult divorce cases, play therapy, complex cases requiring more than 20 sessions, and children of staff employed by the practice.

The practice features a separate waiting room for psychology patients and front office staff dedicated to managing their schedules. “For anyone who’s trying to make a psychology appointment but can’t be seen in an efficient manner or wants a different day or time, we keep an ongoing move-up list,” Dr. Einhorn said. “If a family calls to cancel an appointment, the front desk person who makes that cancellation will fill out a slip and give it to one of our psychology schedulers. That person will create a move-up list and start filling that appointment. If there’s a cancellation, it’s rare that it goes unfilled.”

Key forms for parents to complete include informed consent, a notice of privacy practices, a late cancel/no show policy, an initial intake agreement, and a summary of parent concerns.

Patient and clinician reaction

According to results from a recent survey of parents whose children were seen by a psychologist at Parker Pediatrics and Adolescents, 89% said it was important for their children to receive mental health services in the same location as their medical care, and 96% were satisfied with the services provided. In addition, 93% said that the experience benefited their child, 72% were satisfied with appointment times, and 55% expressed interest in virtual visits via telemedicine. Meanwhile, a survey of parents whose children have not been seen by a psychologist at the practice found that 65% knew a psychologist was on staff, and only 9% said that there were barriers to their child seeing a psychologist there.

Clinicians themselves benefit from having mental health specialists on site for referrals. “It enables you to be more efficient, and it saves time,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “There’s knowledge and confidence gained, and it improves satisfaction because physicians don’t have to stay at the office later filling out referral forms. It meets the needs of your patients and their families, it attracts new patients, and you may be able to make some income on this.”

How to get started

Dr. Rabinowitz recommended that, once clinicians at a pediatric practice commit to expanding their services to include mental and behavioral health care, they should hold a corporate/partner meeting, assign responsibilities, and establish a timeline for implementation. “This is all very important,” he said. “Then you have to talk about what kind of arrangement you want to have. You could employ someone to join your practice, hire an independent contractor, establish a space share agreement, or have an out-of-office arrangement.”

For many years, clinicians at Parker Pediatrics and Adolescents had a psychologist perform ADHD evaluations on a consultative basis. “Then, as we saw a need for mental health services about a decade ago, we hired a part-time psychologist who did testing as well as counseling,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “But that psychologist got very busy, so we hired a full-time psychologist. We continued to hire additional psychologists as need increased.”

Reimbursement issues

Numerous reimbursement barriers to providing mental health services in pediatric primary care exist, he noted, including a lack of payment if mental health codes are used, a lack of “incident to” payments in some areas of the country, existing reimbursement levels, and the fact that same-day billing of physical and mental health often is not allowed. “However, we have found that if we give flu shots during their mental health visit, [insurers] will cover the flu shot,” he said. “Reimbursement for screening is sometimes not covered very well.”

One reimbursement option is the fee-for-service/concierge model, “but that’s not an economic option for many,” he said. “You can’t see Medicaid patients in that model.” Joining a mental health networks is feasible, “but there is poor reimbursement,” he said. “It also creates another layer of administration.”

He recommends financial integration, “but you need to research your options because a lot of it is state dependent.” Other options include grants, insurance contracts, and seeking permission from Medicaid.

Mental health CPT codes that mental health clinicians at the practice commonly use include bill by time (CPT code 99214/15); psychotherapy session that lasts 16-37 minutes (CPT code 90832); psychotherapy session that lasts 38-52 minutes (CPT code 90834); and psychotherapy session that lasts more than 53 minutes (CPT code 90837). Clinicians also can bill by interactive complexity (CPT code 90785) and psychotherapy for crisis (CPT code 90839).

Dr. Rabinowitz and Dr. Einhorn reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – The way Jay Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, sees it, providing mental and behavioral health care services in your primary care pediatrics practice is a win-win for patients, parents, and clinicians.

For one thing, children with mental and behavioral issues – especially depression and anxiety – make up a good chunk of any pediatrician’s workday. Dr. Rabinowitz, clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Aurora, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It is the most costly issue in children’s health care today.”

According to “Behavioral Health Integration in Pediatric Primary Care,” a report supported by the Milbank Memorial Fund, one in five children aged 9-17 years have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder, and up to 70% of children in the juvenile justice system have a mental health disorder. The report also found that the treatment of mental health disorders accounts for the most costly childhood medical expenditure, and that between 15% and 20% of children with psychiatric disorders receive specialty care; the rest see their primary care provider. A long-term cost analysis showed significant cost savings: $1 spent on collaborative care saves $6.50 on health care costs.

More recently, the Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC) found that only 50% of adolescents with depression are diagnosed before reaching adulthood (Pediatrics. March 2018;141[3]:e20174081). As many as two out of three youth with depression are not identified by their pediatrician and do not receive any kind of care.

“Even when diagnosed, only half of these patients are treated appropriately,” said Dr. Rabinowitz, who also practices at Parker (Colo.) Pediatrics and Adolescents.

The guidelines also found that reliance on self-report depression checklists alone lead to substantial numbers of false-positive and false-negative cases. “Primary care providers will benefit from having access to ongoing consultation with mental health providers,” according to the guidelines.

“Integrative care was associated with significant decreases in depression scores, and improved response and remission rates at 12 months, compared with treatment as usual,” Dr. Rabinowitz said.

Providing mental health services in a primary care pediatrics setting also makes sense because there’s a shortage of psychiatrists and psychologists to see them, and it enables patients to get evaluated quicker. “It’s convenient, and it reduces stigma,” he added. “It’s a familiar setting, a familiar provider, and they’re more likely to initiate counseling. Nationwide, 50% of patients who are referred for mental health do not make their initial appointment. Think about that. If you had diabetics in your practice and only 50% would go to the endocrinologist, what would you think?”

How Dr. Rabinowitz and his partners got started

Dr. Rabinowitz and his colleagues created an integrated care model in 2008 by adding a psychologist to their practice, but before doing that, they asked parents of children with mental and behavioral health issues what type of insurance they had. Then they obtained a referral list from the family’s insurer and hoped for the best. “Sometimes I referred to someone I may not have heard of,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “Usually I did not get follow-up reports, or even know for sure if the patient ever went.”

Today, Parker Pediatrics and Adolescents employs three doctoral-level psychologists: one full-time, one three-quarter time, and one half-time, as well as one master’s-level therapist who works half-time.

“On any given day, we have at least two counselors in our office,” said Lindsey Einhorn, PhD, a licensed clinical psychologist who joined the practice in 2011. She and her colleagues care for children and teens with ADHD, depression, anxiety, behavioral and adjustment disorders, drug counseling, behavioral addictions, social struggles such as bullying, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), loss, hair or eyelash pulling, mood dysregulation, and sibling conflict. They refer for educational testing, comprehensive psychological evaluations, difficult divorce cases, play therapy, complex cases requiring more than 20 sessions, and children of staff employed by the practice.

The practice features a separate waiting room for psychology patients and front office staff dedicated to managing their schedules. “For anyone who’s trying to make a psychology appointment but can’t be seen in an efficient manner or wants a different day or time, we keep an ongoing move-up list,” Dr. Einhorn said. “If a family calls to cancel an appointment, the front desk person who makes that cancellation will fill out a slip and give it to one of our psychology schedulers. That person will create a move-up list and start filling that appointment. If there’s a cancellation, it’s rare that it goes unfilled.”

Key forms for parents to complete include informed consent, a notice of privacy practices, a late cancel/no show policy, an initial intake agreement, and a summary of parent concerns.

Patient and clinician reaction

According to results from a recent survey of parents whose children were seen by a psychologist at Parker Pediatrics and Adolescents, 89% said it was important for their children to receive mental health services in the same location as their medical care, and 96% were satisfied with the services provided. In addition, 93% said that the experience benefited their child, 72% were satisfied with appointment times, and 55% expressed interest in virtual visits via telemedicine. Meanwhile, a survey of parents whose children have not been seen by a psychologist at the practice found that 65% knew a psychologist was on staff, and only 9% said that there were barriers to their child seeing a psychologist there.

Clinicians themselves benefit from having mental health specialists on site for referrals. “It enables you to be more efficient, and it saves time,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “There’s knowledge and confidence gained, and it improves satisfaction because physicians don’t have to stay at the office later filling out referral forms. It meets the needs of your patients and their families, it attracts new patients, and you may be able to make some income on this.”

How to get started

Dr. Rabinowitz recommended that, once clinicians at a pediatric practice commit to expanding their services to include mental and behavioral health care, they should hold a corporate/partner meeting, assign responsibilities, and establish a timeline for implementation. “This is all very important,” he said. “Then you have to talk about what kind of arrangement you want to have. You could employ someone to join your practice, hire an independent contractor, establish a space share agreement, or have an out-of-office arrangement.”

For many years, clinicians at Parker Pediatrics and Adolescents had a psychologist perform ADHD evaluations on a consultative basis. “Then, as we saw a need for mental health services about a decade ago, we hired a part-time psychologist who did testing as well as counseling,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “But that psychologist got very busy, so we hired a full-time psychologist. We continued to hire additional psychologists as need increased.”

Reimbursement issues

Numerous reimbursement barriers to providing mental health services in pediatric primary care exist, he noted, including a lack of payment if mental health codes are used, a lack of “incident to” payments in some areas of the country, existing reimbursement levels, and the fact that same-day billing of physical and mental health often is not allowed. “However, we have found that if we give flu shots during their mental health visit, [insurers] will cover the flu shot,” he said. “Reimbursement for screening is sometimes not covered very well.”

One reimbursement option is the fee-for-service/concierge model, “but that’s not an economic option for many,” he said. “You can’t see Medicaid patients in that model.” Joining a mental health networks is feasible, “but there is poor reimbursement,” he said. “It also creates another layer of administration.”

He recommends financial integration, “but you need to research your options because a lot of it is state dependent.” Other options include grants, insurance contracts, and seeking permission from Medicaid.

Mental health CPT codes that mental health clinicians at the practice commonly use include bill by time (CPT code 99214/15); psychotherapy session that lasts 16-37 minutes (CPT code 90832); psychotherapy session that lasts 38-52 minutes (CPT code 90834); and psychotherapy session that lasts more than 53 minutes (CPT code 90837). Clinicians also can bill by interactive complexity (CPT code 90785) and psychotherapy for crisis (CPT code 90839).

Dr. Rabinowitz and Dr. Einhorn reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2019

Tide beginning to turn on vaccine hesitancy

NEW ORLEANS –

The shift began with the measles outbreak in Southern California in late 2014, he said. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 125 measles cases with rash that occurred between Dec. 28, 2014, and Feb. 8, 2015, were confirmed in U.S. residents. Of these, 100 were California residents (MMWR. 2015 Feb 20;64[06];153-4).

“This outbreak spread ultimately to 25 states and involved 189 people,” Dr. Offit said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It was in the news almost every day. As a consequence, there were measles outbreaks in New York, New Jersey, Florida, Oregon, and Texas, and Washington, which began to turn the public sentiment against the antivaccine movement.”

Even longstanding skeptics are changing their tune. Dr. Offit, professor of pediatrics in the division of infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, cited a recent study from the Autism Science Foundation which found that 85% of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder don’t believe that vaccines cause the condition. “Although there will be parents who continue to believe that vaccines cause autism, most parents of children with autism don’t believe that,” he said. “Also, it’s a little hard to make your case that vaccines are dangerous and that you shouldn’t get them in the midst of outbreaks.”

Perhaps the greatest pushback against antivaccination efforts has been made in the legal arena. In 2019 alone, legislators in California banned parents from not vaccinating their kids because of personal beliefs, while lawmakers in New York repealed the religious exemption to vaccinate, those in Maine repealed the religious and philosophical exemption, those in New Jersey required detailed written explanation for religious exemption, and those in Washington State repealed the philosophical exemption for the MMR vaccine.

Pushback also is apparent on various social media platforms. For example, Dr. Offit said, Pinterest restricts vaccine search results to curb the spread of misinformation, YouTube removes ads from antivaccine channels, Amazon Prime has pulled antivaccination documentaries from its video service, and Facebook has taken steps to curb misinformation about vaccines. “With outbreaks and with children suffering, the media and public sentiment has largely turned against those who are vehemently against vaccines,” he said. “I’m talking about an angry, politically connected, lawyer-backed group of people who are conspiracy theorists, [those] who no matter what you say, they’re going to believe there’s a conspiracy theory to hurt their children and not believe you. When that group becomes big enough and you start to see outbreaks like we’ve seen, then it becomes an issue. That’s where it comes down to legislation. Is it your inalienable right as a U.S. citizen to allow your child to catch and transmit a potentially fatal infection? That’s what we’re struggling with now.”

When meeting with parents who are skeptical about vaccines or refuse their children to have them, Dr. Offit advises clinicians to “go down swinging” in favor of vaccination. He shared how his wife, Bonnie, a pediatrician who practices in suburban Philadelphia, counsels parents who raise such concerns. “The way she handled it initially was to do the best she could to eventually get people vaccinated,” he said. “She was successful about one-quarter of the time. Then she drew a line. She started saying to parents, ‘Look; don’t put me in a position where you are asking me to practice substandard care. I can’t send them out of this room knowing that there’s more measles out there, knowing that there’s mumps out there, knowing that there’s whooping cough out there, knowing that there’s pneumococcus and varicella out there. If this child leaves this office and is hurt by any of those viruses or bacteria and I knew I could have done something to prevent it, I couldn’t live with myself. If you’re going to let this child out without being vaccinated I can’t see you anymore because I’m responsible for the health of this child.’ With that [approach], she has been far more successful. Because at some level, if you continue to see that patient, you’re tacitly agreeing that it’s okay to [not vaccinate].”

In 2000, Dr. Offit and colleagues created the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, which provides complete, up-to-date, and reliable information about vaccines to parents and clinicians. It summarizes the purpose of each vaccine, and the relative risks and benefits in easy-to-read language. The CDC also maintains updated information about vaccines and immunizations on its web site. For his part, Dr. Offit tells parents that passing on an opportunity to vaccinate their child is not a risk-free choice. “If you choose not to get a vaccine you probably will get away with it, but you might not,” he said. “You are playing a game of Russian roulette. It may not be five empty chambers and one bullet, but maybe it’s 100,000 empty chambers and one bullet. There’s a bullet there.”

Dr. Offit reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS –

The shift began with the measles outbreak in Southern California in late 2014, he said. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 125 measles cases with rash that occurred between Dec. 28, 2014, and Feb. 8, 2015, were confirmed in U.S. residents. Of these, 100 were California residents (MMWR. 2015 Feb 20;64[06];153-4).