User login

Know the red flags for synaptic autoimmune psychosis

BARCELONA – Consider the possibility of an autoantibody-related etiology in all cases of first-onset psychosis, Josep Dalmau, MD, PhD, urged at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“There are patients in our clinics all of us – neurologists and psychiatrists – are missing. These patients are believed to have psychiatric presentations, but they do not. They are autoimmune,” said Dr. Dalmau, professor of neurology at the University of Barcelona.

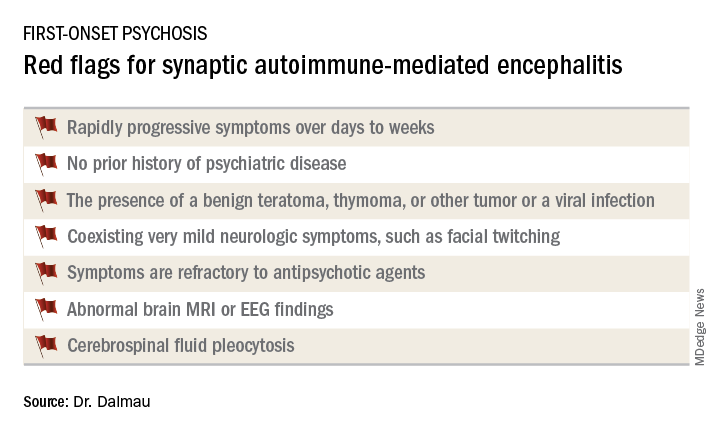

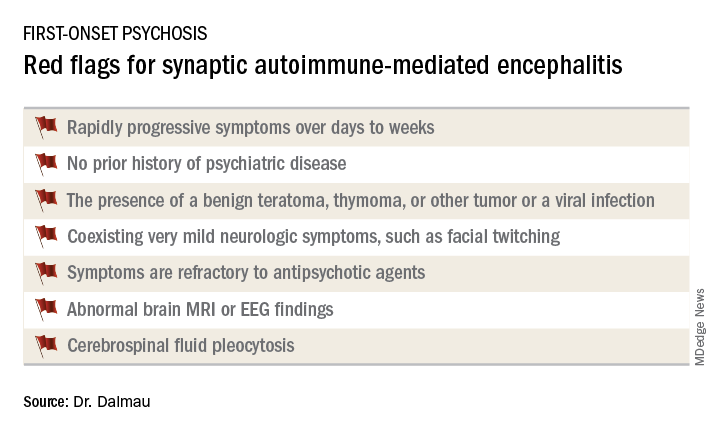

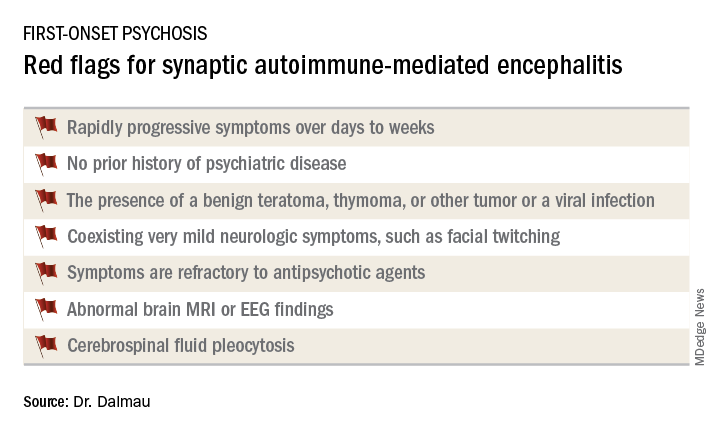

Dr. Dalmau urged psychiatrists to become familiar with the red flags suggestive of synaptic autoimmunity as the underlying cause of first-episode, out-of-the-blue psychosis.

“If you have a patient with a classical presentation of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, you probably won’t find antibodies,” according to the neurologist.

It’s important to have a high index of suspicion, because anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis is treatable with immunotherapy. And firm evidence shows that earlier recognition and treatment lead to improved outcomes. Also, the disorder is refractory to antipsychotics; indeed,

Manifestations of anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis follow a characteristic pattern, beginning with a prodromal flulike phase lasting several days to a week. This is followed by acute-onset bizarre behavioral changes, irritability, and psychosis with delusions and/or hallucinations, often progressing to catatonia. After 1-4 weeks of this, florid neurologic symptoms usually appear, including seizures, abnormal movements, autonomic dysregulation, and hypoventilation requiring prolonged ICU support for weeks to months. This is followed by a prolonged recovery phase lasting 5-24 months, and a period marked by deficits in executive function and working memory, impulsivity, and disinhibition. Impressively, the patient has no memory of the illness.

In one large series of patients with confirmed anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis reported by Dr. Dalmau and coinvestigators, psychiatric symptoms occurred in isolation without subsequent neurologic involvement in just 4% of cases (JAMA Neurol. 2013 Sep 1;70[9]:1133-9).

Dr. Dalmau was senior author of an international cohort study including 577 patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis with serial follow-up for 24 months. The study provided an unprecedented picture of the epidemiology and clinical features of the disorder.

“It’s a disease predominantly of women and young people,” he observed.

Indeed, the median age of the study population was 21 years, and 37% of subjects were less than 18 years of age. Roughly 80% of patients were female and most of them had a benign ovarian teratoma, which played a key role in their neuropsychiatric disease (Lancet Neurol. 2013 Feb;12[2]:157-65). These benign tumors express the NMDA receptor in ectopic nerve tissue, triggering a systemic immune response.

One or more relapses – again treatable via immunotherapy – occurred in 12% of patients during 24 months of follow-up.

When a red flag suggestive of synaptic autoimmunity is present, it’s important to obtain a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample for analysis, along with an EEG and/or brain MRI.

“I don’t know if you as psychiatrists are set up to do spinal taps in all persons with first presentation of psychosis, but this would be my suggestion. It’s extremely useful in this situation,” Dr. Dalmau said.

The vast majority of patients with anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis have CSF pleocytosis with a mild lymphocytic predominance. The MRI is abnormal in about 35% of cases. EEG abnormalities are common but nonspecific. The diagnosis is confirmed by identification of anti–NMDA receptor antibodies in the CSF.

First-line therapy is corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and/or plasma exchange to remove the pathogenic antibodies, along with resection of the tumor if present. These treatments are effective in almost half of affected patients. When they’re not, the second-line options are rituximab (Rituxan) and cyclophosphamide, alone or combined.

Antibodies to the NMDA receptor are far and away the most common cause of synaptic autoimmunity-induced psychosis, but other targets of autoimmunity have been documented as well, including the alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor, contactin-associated protein-like 2 (CASPR2), and neurexin-3-alpha.

Dr. Dalmau and various collaborators continue to advance the understanding of this novel category of neuropsychiatric disease. They have developed a simple 5-point score, known as the NEOS score, that predicts 1-year functional status in patients with anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis (Neurology. 2018 Dec 21. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006783). He and his colleagues have also recently shown in a prospective study that herpes simplex encephalitis can result in an autoimmune encephalitis, with NMDA receptor antibodies present in most cases (Lancet Neurol. 2018 Sep;17[9]:760-72).

Dr. Dalmau’s research is supported by the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Spanish Ministry of Health, and Spanish research foundations. He reported receiving royalties from the use of several neuronal antibody tests.

BARCELONA – Consider the possibility of an autoantibody-related etiology in all cases of first-onset psychosis, Josep Dalmau, MD, PhD, urged at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“There are patients in our clinics all of us – neurologists and psychiatrists – are missing. These patients are believed to have psychiatric presentations, but they do not. They are autoimmune,” said Dr. Dalmau, professor of neurology at the University of Barcelona.

Dr. Dalmau urged psychiatrists to become familiar with the red flags suggestive of synaptic autoimmunity as the underlying cause of first-episode, out-of-the-blue psychosis.

“If you have a patient with a classical presentation of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, you probably won’t find antibodies,” according to the neurologist.

It’s important to have a high index of suspicion, because anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis is treatable with immunotherapy. And firm evidence shows that earlier recognition and treatment lead to improved outcomes. Also, the disorder is refractory to antipsychotics; indeed,

Manifestations of anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis follow a characteristic pattern, beginning with a prodromal flulike phase lasting several days to a week. This is followed by acute-onset bizarre behavioral changes, irritability, and psychosis with delusions and/or hallucinations, often progressing to catatonia. After 1-4 weeks of this, florid neurologic symptoms usually appear, including seizures, abnormal movements, autonomic dysregulation, and hypoventilation requiring prolonged ICU support for weeks to months. This is followed by a prolonged recovery phase lasting 5-24 months, and a period marked by deficits in executive function and working memory, impulsivity, and disinhibition. Impressively, the patient has no memory of the illness.

In one large series of patients with confirmed anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis reported by Dr. Dalmau and coinvestigators, psychiatric symptoms occurred in isolation without subsequent neurologic involvement in just 4% of cases (JAMA Neurol. 2013 Sep 1;70[9]:1133-9).

Dr. Dalmau was senior author of an international cohort study including 577 patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis with serial follow-up for 24 months. The study provided an unprecedented picture of the epidemiology and clinical features of the disorder.

“It’s a disease predominantly of women and young people,” he observed.

Indeed, the median age of the study population was 21 years, and 37% of subjects were less than 18 years of age. Roughly 80% of patients were female and most of them had a benign ovarian teratoma, which played a key role in their neuropsychiatric disease (Lancet Neurol. 2013 Feb;12[2]:157-65). These benign tumors express the NMDA receptor in ectopic nerve tissue, triggering a systemic immune response.

One or more relapses – again treatable via immunotherapy – occurred in 12% of patients during 24 months of follow-up.

When a red flag suggestive of synaptic autoimmunity is present, it’s important to obtain a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample for analysis, along with an EEG and/or brain MRI.

“I don’t know if you as psychiatrists are set up to do spinal taps in all persons with first presentation of psychosis, but this would be my suggestion. It’s extremely useful in this situation,” Dr. Dalmau said.

The vast majority of patients with anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis have CSF pleocytosis with a mild lymphocytic predominance. The MRI is abnormal in about 35% of cases. EEG abnormalities are common but nonspecific. The diagnosis is confirmed by identification of anti–NMDA receptor antibodies in the CSF.

First-line therapy is corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and/or plasma exchange to remove the pathogenic antibodies, along with resection of the tumor if present. These treatments are effective in almost half of affected patients. When they’re not, the second-line options are rituximab (Rituxan) and cyclophosphamide, alone or combined.

Antibodies to the NMDA receptor are far and away the most common cause of synaptic autoimmunity-induced psychosis, but other targets of autoimmunity have been documented as well, including the alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor, contactin-associated protein-like 2 (CASPR2), and neurexin-3-alpha.

Dr. Dalmau and various collaborators continue to advance the understanding of this novel category of neuropsychiatric disease. They have developed a simple 5-point score, known as the NEOS score, that predicts 1-year functional status in patients with anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis (Neurology. 2018 Dec 21. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006783). He and his colleagues have also recently shown in a prospective study that herpes simplex encephalitis can result in an autoimmune encephalitis, with NMDA receptor antibodies present in most cases (Lancet Neurol. 2018 Sep;17[9]:760-72).

Dr. Dalmau’s research is supported by the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Spanish Ministry of Health, and Spanish research foundations. He reported receiving royalties from the use of several neuronal antibody tests.

BARCELONA – Consider the possibility of an autoantibody-related etiology in all cases of first-onset psychosis, Josep Dalmau, MD, PhD, urged at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“There are patients in our clinics all of us – neurologists and psychiatrists – are missing. These patients are believed to have psychiatric presentations, but they do not. They are autoimmune,” said Dr. Dalmau, professor of neurology at the University of Barcelona.

Dr. Dalmau urged psychiatrists to become familiar with the red flags suggestive of synaptic autoimmunity as the underlying cause of first-episode, out-of-the-blue psychosis.

“If you have a patient with a classical presentation of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, you probably won’t find antibodies,” according to the neurologist.

It’s important to have a high index of suspicion, because anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis is treatable with immunotherapy. And firm evidence shows that earlier recognition and treatment lead to improved outcomes. Also, the disorder is refractory to antipsychotics; indeed,

Manifestations of anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis follow a characteristic pattern, beginning with a prodromal flulike phase lasting several days to a week. This is followed by acute-onset bizarre behavioral changes, irritability, and psychosis with delusions and/or hallucinations, often progressing to catatonia. After 1-4 weeks of this, florid neurologic symptoms usually appear, including seizures, abnormal movements, autonomic dysregulation, and hypoventilation requiring prolonged ICU support for weeks to months. This is followed by a prolonged recovery phase lasting 5-24 months, and a period marked by deficits in executive function and working memory, impulsivity, and disinhibition. Impressively, the patient has no memory of the illness.

In one large series of patients with confirmed anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis reported by Dr. Dalmau and coinvestigators, psychiatric symptoms occurred in isolation without subsequent neurologic involvement in just 4% of cases (JAMA Neurol. 2013 Sep 1;70[9]:1133-9).

Dr. Dalmau was senior author of an international cohort study including 577 patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis with serial follow-up for 24 months. The study provided an unprecedented picture of the epidemiology and clinical features of the disorder.

“It’s a disease predominantly of women and young people,” he observed.

Indeed, the median age of the study population was 21 years, and 37% of subjects were less than 18 years of age. Roughly 80% of patients were female and most of them had a benign ovarian teratoma, which played a key role in their neuropsychiatric disease (Lancet Neurol. 2013 Feb;12[2]:157-65). These benign tumors express the NMDA receptor in ectopic nerve tissue, triggering a systemic immune response.

One or more relapses – again treatable via immunotherapy – occurred in 12% of patients during 24 months of follow-up.

When a red flag suggestive of synaptic autoimmunity is present, it’s important to obtain a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample for analysis, along with an EEG and/or brain MRI.

“I don’t know if you as psychiatrists are set up to do spinal taps in all persons with first presentation of psychosis, but this would be my suggestion. It’s extremely useful in this situation,” Dr. Dalmau said.

The vast majority of patients with anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis have CSF pleocytosis with a mild lymphocytic predominance. The MRI is abnormal in about 35% of cases. EEG abnormalities are common but nonspecific. The diagnosis is confirmed by identification of anti–NMDA receptor antibodies in the CSF.

First-line therapy is corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and/or plasma exchange to remove the pathogenic antibodies, along with resection of the tumor if present. These treatments are effective in almost half of affected patients. When they’re not, the second-line options are rituximab (Rituxan) and cyclophosphamide, alone or combined.

Antibodies to the NMDA receptor are far and away the most common cause of synaptic autoimmunity-induced psychosis, but other targets of autoimmunity have been documented as well, including the alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor, contactin-associated protein-like 2 (CASPR2), and neurexin-3-alpha.

Dr. Dalmau and various collaborators continue to advance the understanding of this novel category of neuropsychiatric disease. They have developed a simple 5-point score, known as the NEOS score, that predicts 1-year functional status in patients with anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis (Neurology. 2018 Dec 21. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006783). He and his colleagues have also recently shown in a prospective study that herpes simplex encephalitis can result in an autoimmune encephalitis, with NMDA receptor antibodies present in most cases (Lancet Neurol. 2018 Sep;17[9]:760-72).

Dr. Dalmau’s research is supported by the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Spanish Ministry of Health, and Spanish research foundations. He reported receiving royalties from the use of several neuronal antibody tests.

REPORTING FROM THE ECNP CONGRESS

Single-dose propranolol tied to ‘selective erasure’ of anxiety disorders

BARCELONA – A single 40-mg dose of oral propranolol, judiciously timed, constitutes an outside-the-box yet highly promising treatment for anxiety disorders, and perhaps for posttraumatic stress disorder as well, Marieke Soeter, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The concept here is that the beta-blocker, when given with a brief therapist-led reactivation of a fear memory, blocks beta-adrenergic receptors in the brain so as to interfere with the specific proteins required for reconsolidation of that memory, thereby disrupting the reconsolidation process and neutralizing subsequent expression of that memory in its toxic form. In effect, timely administration of one dose of propranolol, a drug that readily crosses the blood/brain barrier, achieves pharmacologically induced amnesia regarding the learned fear, explained Dr. Soeter, a clinical psychologist at TNO, the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, an independent nonprofit translational research organization.

“It looks like permanent fear erasure. You can never say that something is erased, but we have not been able to get it back,” she said. “Propranolol achieves selective erasure: It targets the emotional component, but knowledge is intact. They know what happened, but they aren’t scared anymore. The fear association is affected, but not the innate fear response to a threat stimulus, so it doesn’t alter reactions to potentially dangerous situations, which is important. If there is a bomb, they still know to run away from it.”

This single-session therapy addressing what psychologists call fear memory reconsolidation is totally outside the box relative to contemporary psychotherapy for anxiety disorders, which typically entails gradual fear extinction learning requiring multiple treatment sessions. But contemporary psychotherapy for anxiety disorders leaves much room for improvement, given that up to 60% of patients experience relapse. That’s probably because the original fear memory remains intact and resurfaces at some point despite initial treatment success, according to Dr. Soeter.

Nearly 2 decades ago, other investigators showed in animal studies that fear memories are not necessarily permanent. Rather, they are modifiable, and even erasable, during the vulnerable period that occurs when the memories are reactivated and become labile.

Later, Dr. Soeter – then at the University of Amsterdam – and her colleagues demonstrated the same phenomenon using Pavlovian fear-conditioning techniques involving pictures and electric shocks in healthy human volunteers. They showed that a dose of propranolol given before memory reactivation blocked the fear response, while nadolol, a beta-blocker that does not cross the blood/brain barrier, did not.

However, since the fear memories they could ethically induce in the psychology laboratory are far less intense than those experienced by patients with anxiety disorders, the researchers next conducted a randomized, double-blind clinical trial in 45 individuals with arachnophobia. Fifteen received 40 mg of propranolol after spending 2 minutes in proximity to a large tarantula, 15 got placebo, and another 15 received propranolol without exposure to a tarantula. One week later, all patients who received propranolol with spider exposure were able to approach and actually pet the tarantula. Pharmacologic disruption of reconsolidation and storage of their fear memory had turned avoidance behavior into approach behavior. This benefit was maintained for at least a year after the brief treatment session (Biol Psychiatry. 2015 Dec 15;78[12]:880-6).

“Interestingly, there was no direct effect of propranolol on spider beliefs. Therefore, do we need treatment that targets the cognitive level? These findings challenge one of the fundamental tenets of cognitive-behavioral therapy that emphasizes changes in cognition as central to behavioral modification,” Dr. Soeter said.

Most recently, she and a coinvestigator have been working to pin down the precise conditions under which memory reconsolidation can be targeted to extinguish fear memories. They have shown in a 30-subject study that the process is both time- and sleep-dependent. The propranolol must be given within roughly an hour before to 1 hour after therapeutic reactivation of the fear memory to be effective. And sleep is an absolute necessity: When subjects were rechallenged 12 hours after memory reactivation and administration of propranolol earlier on the same day, with no opportunity for sleep, there was no therapeutic effect: The disturbing fear memory was elicited. However, when subjects were rechallenged 12 hours after taking propranolol the previous day – that is, after a night’s sleep – the fear memory was gone (Nat Commun. 2018 Apr 3;9[1]:1316. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03659-1).

“Postretrieval amnesia requires sleep to happen. ,” Dr. Soeter said. It’s still unclear, however, how much sleep is required. Perhaps a nap will turn out to be sufficient, she said.

Colleagues at the University of Amsterdam are now using single-dose propranolol-based therapy in patients with a wide range of phobias.

“The effects are pretty amazing,” Dr. Soeter said. “Everything is treatable. It’s almost too good to be true, but these are our findings.”

Based upon her favorable anecdotal experience in treating a Dutch military veteran with severe combat-related PTSD of 10 years’ duration which had proved resistant to multiple conventional and unconventional interventions, a pilot study of single-dose propranolol with traumatic memory reactivation is now being planned in patients with war-related PTSD.

“After one pill and a 20-minute session, this veteran with severe chronic PTSD has no more nightmares, insomnia, or alcohol problems, and he now travels the world,” she said.

Her research met with an enthusiastic reception from other speakers at the ECNP session on PTSD. Eric Vermetten, MD, PhD, welcomed the concept that pharmacologic therapy upon reexposure to fearful cues can impede the molecular and cellular cascade required to reestablish fearful memories. This also is the basis for the extremely encouraging, albeit preliminary, clinical data on ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, as well as 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) for therapeutic manipulation of trauma memories.

“Targeting reconsolidation of existing fear memories is worthy of looking into further,” declared Dr. Vermetten, professor of psychiatry at Leiden (the Netherlands) University and a military mental health researcher for the Dutch Ministry of Defense.

New thinking regarding pharmacotherapy for PTSD is sorely needed, he added. He endorsed a consensus statement by the PTSD Psychopharmacology Working Group that decried what was termed a crisis in pharmacotherapy of PTSD (Biol Psychiatry. 2017 Oct 1;82[7]:e51-e59. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.03.007. Epub 2017 Mar 14).

“We only have two [Food and Drug Administration]-approved medications for PTSD – sertraline and paroxetine – and they were approved back in 2001,” Dr. Vermetten noted. “Research has stalled, and there is a void in new drug development.”

Dr. Soeter’s study of the time- and sleep-dependent nature of propranolol-induced amnesia was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, where she is employed.

BARCELONA – A single 40-mg dose of oral propranolol, judiciously timed, constitutes an outside-the-box yet highly promising treatment for anxiety disorders, and perhaps for posttraumatic stress disorder as well, Marieke Soeter, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The concept here is that the beta-blocker, when given with a brief therapist-led reactivation of a fear memory, blocks beta-adrenergic receptors in the brain so as to interfere with the specific proteins required for reconsolidation of that memory, thereby disrupting the reconsolidation process and neutralizing subsequent expression of that memory in its toxic form. In effect, timely administration of one dose of propranolol, a drug that readily crosses the blood/brain barrier, achieves pharmacologically induced amnesia regarding the learned fear, explained Dr. Soeter, a clinical psychologist at TNO, the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, an independent nonprofit translational research organization.

“It looks like permanent fear erasure. You can never say that something is erased, but we have not been able to get it back,” she said. “Propranolol achieves selective erasure: It targets the emotional component, but knowledge is intact. They know what happened, but they aren’t scared anymore. The fear association is affected, but not the innate fear response to a threat stimulus, so it doesn’t alter reactions to potentially dangerous situations, which is important. If there is a bomb, they still know to run away from it.”

This single-session therapy addressing what psychologists call fear memory reconsolidation is totally outside the box relative to contemporary psychotherapy for anxiety disorders, which typically entails gradual fear extinction learning requiring multiple treatment sessions. But contemporary psychotherapy for anxiety disorders leaves much room for improvement, given that up to 60% of patients experience relapse. That’s probably because the original fear memory remains intact and resurfaces at some point despite initial treatment success, according to Dr. Soeter.

Nearly 2 decades ago, other investigators showed in animal studies that fear memories are not necessarily permanent. Rather, they are modifiable, and even erasable, during the vulnerable period that occurs when the memories are reactivated and become labile.

Later, Dr. Soeter – then at the University of Amsterdam – and her colleagues demonstrated the same phenomenon using Pavlovian fear-conditioning techniques involving pictures and electric shocks in healthy human volunteers. They showed that a dose of propranolol given before memory reactivation blocked the fear response, while nadolol, a beta-blocker that does not cross the blood/brain barrier, did not.

However, since the fear memories they could ethically induce in the psychology laboratory are far less intense than those experienced by patients with anxiety disorders, the researchers next conducted a randomized, double-blind clinical trial in 45 individuals with arachnophobia. Fifteen received 40 mg of propranolol after spending 2 minutes in proximity to a large tarantula, 15 got placebo, and another 15 received propranolol without exposure to a tarantula. One week later, all patients who received propranolol with spider exposure were able to approach and actually pet the tarantula. Pharmacologic disruption of reconsolidation and storage of their fear memory had turned avoidance behavior into approach behavior. This benefit was maintained for at least a year after the brief treatment session (Biol Psychiatry. 2015 Dec 15;78[12]:880-6).

“Interestingly, there was no direct effect of propranolol on spider beliefs. Therefore, do we need treatment that targets the cognitive level? These findings challenge one of the fundamental tenets of cognitive-behavioral therapy that emphasizes changes in cognition as central to behavioral modification,” Dr. Soeter said.

Most recently, she and a coinvestigator have been working to pin down the precise conditions under which memory reconsolidation can be targeted to extinguish fear memories. They have shown in a 30-subject study that the process is both time- and sleep-dependent. The propranolol must be given within roughly an hour before to 1 hour after therapeutic reactivation of the fear memory to be effective. And sleep is an absolute necessity: When subjects were rechallenged 12 hours after memory reactivation and administration of propranolol earlier on the same day, with no opportunity for sleep, there was no therapeutic effect: The disturbing fear memory was elicited. However, when subjects were rechallenged 12 hours after taking propranolol the previous day – that is, after a night’s sleep – the fear memory was gone (Nat Commun. 2018 Apr 3;9[1]:1316. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03659-1).

“Postretrieval amnesia requires sleep to happen. ,” Dr. Soeter said. It’s still unclear, however, how much sleep is required. Perhaps a nap will turn out to be sufficient, she said.

Colleagues at the University of Amsterdam are now using single-dose propranolol-based therapy in patients with a wide range of phobias.

“The effects are pretty amazing,” Dr. Soeter said. “Everything is treatable. It’s almost too good to be true, but these are our findings.”

Based upon her favorable anecdotal experience in treating a Dutch military veteran with severe combat-related PTSD of 10 years’ duration which had proved resistant to multiple conventional and unconventional interventions, a pilot study of single-dose propranolol with traumatic memory reactivation is now being planned in patients with war-related PTSD.

“After one pill and a 20-minute session, this veteran with severe chronic PTSD has no more nightmares, insomnia, or alcohol problems, and he now travels the world,” she said.

Her research met with an enthusiastic reception from other speakers at the ECNP session on PTSD. Eric Vermetten, MD, PhD, welcomed the concept that pharmacologic therapy upon reexposure to fearful cues can impede the molecular and cellular cascade required to reestablish fearful memories. This also is the basis for the extremely encouraging, albeit preliminary, clinical data on ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, as well as 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) for therapeutic manipulation of trauma memories.

“Targeting reconsolidation of existing fear memories is worthy of looking into further,” declared Dr. Vermetten, professor of psychiatry at Leiden (the Netherlands) University and a military mental health researcher for the Dutch Ministry of Defense.

New thinking regarding pharmacotherapy for PTSD is sorely needed, he added. He endorsed a consensus statement by the PTSD Psychopharmacology Working Group that decried what was termed a crisis in pharmacotherapy of PTSD (Biol Psychiatry. 2017 Oct 1;82[7]:e51-e59. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.03.007. Epub 2017 Mar 14).

“We only have two [Food and Drug Administration]-approved medications for PTSD – sertraline and paroxetine – and they were approved back in 2001,” Dr. Vermetten noted. “Research has stalled, and there is a void in new drug development.”

Dr. Soeter’s study of the time- and sleep-dependent nature of propranolol-induced amnesia was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, where she is employed.

BARCELONA – A single 40-mg dose of oral propranolol, judiciously timed, constitutes an outside-the-box yet highly promising treatment for anxiety disorders, and perhaps for posttraumatic stress disorder as well, Marieke Soeter, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The concept here is that the beta-blocker, when given with a brief therapist-led reactivation of a fear memory, blocks beta-adrenergic receptors in the brain so as to interfere with the specific proteins required for reconsolidation of that memory, thereby disrupting the reconsolidation process and neutralizing subsequent expression of that memory in its toxic form. In effect, timely administration of one dose of propranolol, a drug that readily crosses the blood/brain barrier, achieves pharmacologically induced amnesia regarding the learned fear, explained Dr. Soeter, a clinical psychologist at TNO, the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, an independent nonprofit translational research organization.

“It looks like permanent fear erasure. You can never say that something is erased, but we have not been able to get it back,” she said. “Propranolol achieves selective erasure: It targets the emotional component, but knowledge is intact. They know what happened, but they aren’t scared anymore. The fear association is affected, but not the innate fear response to a threat stimulus, so it doesn’t alter reactions to potentially dangerous situations, which is important. If there is a bomb, they still know to run away from it.”

This single-session therapy addressing what psychologists call fear memory reconsolidation is totally outside the box relative to contemporary psychotherapy for anxiety disorders, which typically entails gradual fear extinction learning requiring multiple treatment sessions. But contemporary psychotherapy for anxiety disorders leaves much room for improvement, given that up to 60% of patients experience relapse. That’s probably because the original fear memory remains intact and resurfaces at some point despite initial treatment success, according to Dr. Soeter.

Nearly 2 decades ago, other investigators showed in animal studies that fear memories are not necessarily permanent. Rather, they are modifiable, and even erasable, during the vulnerable period that occurs when the memories are reactivated and become labile.

Later, Dr. Soeter – then at the University of Amsterdam – and her colleagues demonstrated the same phenomenon using Pavlovian fear-conditioning techniques involving pictures and electric shocks in healthy human volunteers. They showed that a dose of propranolol given before memory reactivation blocked the fear response, while nadolol, a beta-blocker that does not cross the blood/brain barrier, did not.

However, since the fear memories they could ethically induce in the psychology laboratory are far less intense than those experienced by patients with anxiety disorders, the researchers next conducted a randomized, double-blind clinical trial in 45 individuals with arachnophobia. Fifteen received 40 mg of propranolol after spending 2 minutes in proximity to a large tarantula, 15 got placebo, and another 15 received propranolol without exposure to a tarantula. One week later, all patients who received propranolol with spider exposure were able to approach and actually pet the tarantula. Pharmacologic disruption of reconsolidation and storage of their fear memory had turned avoidance behavior into approach behavior. This benefit was maintained for at least a year after the brief treatment session (Biol Psychiatry. 2015 Dec 15;78[12]:880-6).

“Interestingly, there was no direct effect of propranolol on spider beliefs. Therefore, do we need treatment that targets the cognitive level? These findings challenge one of the fundamental tenets of cognitive-behavioral therapy that emphasizes changes in cognition as central to behavioral modification,” Dr. Soeter said.

Most recently, she and a coinvestigator have been working to pin down the precise conditions under which memory reconsolidation can be targeted to extinguish fear memories. They have shown in a 30-subject study that the process is both time- and sleep-dependent. The propranolol must be given within roughly an hour before to 1 hour after therapeutic reactivation of the fear memory to be effective. And sleep is an absolute necessity: When subjects were rechallenged 12 hours after memory reactivation and administration of propranolol earlier on the same day, with no opportunity for sleep, there was no therapeutic effect: The disturbing fear memory was elicited. However, when subjects were rechallenged 12 hours after taking propranolol the previous day – that is, after a night’s sleep – the fear memory was gone (Nat Commun. 2018 Apr 3;9[1]:1316. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03659-1).

“Postretrieval amnesia requires sleep to happen. ,” Dr. Soeter said. It’s still unclear, however, how much sleep is required. Perhaps a nap will turn out to be sufficient, she said.

Colleagues at the University of Amsterdam are now using single-dose propranolol-based therapy in patients with a wide range of phobias.

“The effects are pretty amazing,” Dr. Soeter said. “Everything is treatable. It’s almost too good to be true, but these are our findings.”

Based upon her favorable anecdotal experience in treating a Dutch military veteran with severe combat-related PTSD of 10 years’ duration which had proved resistant to multiple conventional and unconventional interventions, a pilot study of single-dose propranolol with traumatic memory reactivation is now being planned in patients with war-related PTSD.

“After one pill and a 20-minute session, this veteran with severe chronic PTSD has no more nightmares, insomnia, or alcohol problems, and he now travels the world,” she said.

Her research met with an enthusiastic reception from other speakers at the ECNP session on PTSD. Eric Vermetten, MD, PhD, welcomed the concept that pharmacologic therapy upon reexposure to fearful cues can impede the molecular and cellular cascade required to reestablish fearful memories. This also is the basis for the extremely encouraging, albeit preliminary, clinical data on ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, as well as 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) for therapeutic manipulation of trauma memories.

“Targeting reconsolidation of existing fear memories is worthy of looking into further,” declared Dr. Vermetten, professor of psychiatry at Leiden (the Netherlands) University and a military mental health researcher for the Dutch Ministry of Defense.

New thinking regarding pharmacotherapy for PTSD is sorely needed, he added. He endorsed a consensus statement by the PTSD Psychopharmacology Working Group that decried what was termed a crisis in pharmacotherapy of PTSD (Biol Psychiatry. 2017 Oct 1;82[7]:e51-e59. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.03.007. Epub 2017 Mar 14).

“We only have two [Food and Drug Administration]-approved medications for PTSD – sertraline and paroxetine – and they were approved back in 2001,” Dr. Vermetten noted. “Research has stalled, and there is a void in new drug development.”

Dr. Soeter’s study of the time- and sleep-dependent nature of propranolol-induced amnesia was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, where she is employed.

REPORTING FROM THE ECNP CONGRESS

Key clinical point: A single 40-mg dose of oral propranolol, judiciously timed, is a highly promising novel treatment for anxiety disorders.

Major finding: The beta-blocker must be given within an hour before to an hour after therapist-facilitated reactivation of the fear memory.

Study details: This study included 30 healthy volunteers who underwent a cued Pavlovian fear-conditioning program.

Disclosures: Dr. Soeter’s study of the time- and sleep-dependent nature of propranolol-induced amnesia was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, where she is employed.

‘Walk and talk’ 3MDR psychotherapy for PTSD

BARCELONA – The therapeutic setting for individual psychotherapy has shifted over the years from the analytic couch, with the therapist discretely tucked out of sight, to facing chairs, a similarly sedentary format. The next evolutionary development might be to plop a patient with posttraumatic stress disorder on an exercise treadmill and don a virtual reality helmet to engage in an interactive motion-assisted form of psychotherapy in which the therapist stands alongside the walking patient while providing guidance on processing traumatic memories, Eric Vermetten, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

He and his colleagues have developed an innovative approach to delivering trauma-focused psychotherapy. They call it Multimodular Motion-Assisted Memory Desensitization and Reconsolidation (3MDR), or more informally, “walk and talk therapy,” explained Dr. Vermetten, professor of psychiatry at Leiden (the Netherlands) University and a military mental health researcher for the Dutch Ministry of Defense.

3MDR is a combination of personalized virtual reality using a headset, multisensory input using self-selected trauma-related pictures, and a dual-attention task borrowed from eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, with treadmill walking throughout the treatment session.

3MDR is designed to boost this process of memory retrieval and reconsolidation by creating a more totally immersive patient experience intended to enhance treatment engagement and overcome behavioral avoidance. Through virtual reality, the PTSD patient literally walks toward his personal fear-related images.

Dr. Vermetten and his coinvestigators came up with 3MDR as a treatment designed for military veterans with chronic, combat-related, treatment-resistant PTSD. The impetus was the evident need for new and better forms of psychotherapy for such patients. Even though an array of evidence-based psychotherapies are available as guideline-recommended first-line treatments for PTSD, individuals with combat-related PTSD have a notoriously low response rate to these interventions, presumably because of the intensity and repetitive nature of their traumatic experiences. Indeed, up to two-thirds of veterans with PTSD experience substantial residual symptoms post treatment such that they still meet diagnostic criteria for the disorder.

3MDR is an amped up form of exposure-based therapy in which patients walk through a personalized virtual reality installation toward self-chosen trauma-related pictures of their deployment. The investigators developed this intensely immersive type of psychotherapy because they believe avoidance and lack of emotional engagement figure prominently in the low success rate of established forms of psychotherapy in combat-related PTSD. The treadmill walking aspect is considered key because of the large body of research showing that walking entails cognitive-motor interactions that facilitate problem solving, the psychiatrist explained.

The investigators recently published a detailed description of the therapeutic rationale for 3MDR and the nuts and bolts of the novel therapy (Front Psychiatry. 2018 May 4;9:176. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00176). Early anecdotal experience has been positive. However, as cochair of the ECNP Traumatic Stress Network, Dr. Vermetten is acutely aware of the need to demonstrate efficacy in rigorous randomized controlled trials.

“This is a way psychotherapy can be shaped in the future. We’re collaborating with various centers across the globe now to see whether this is effective for treatment-resistant PTSD patients,” Dr. Vermetten said.

If those studies prove positive, it will be worthwhile to determine whether 3MDR also has a role as a first-line treatment for earlier-stage PTSD and for forms of the disorder unrelated to military combat, he added.

Funding for the project has been provided by the Dutch Ministry of Defense.

BARCELONA – The therapeutic setting for individual psychotherapy has shifted over the years from the analytic couch, with the therapist discretely tucked out of sight, to facing chairs, a similarly sedentary format. The next evolutionary development might be to plop a patient with posttraumatic stress disorder on an exercise treadmill and don a virtual reality helmet to engage in an interactive motion-assisted form of psychotherapy in which the therapist stands alongside the walking patient while providing guidance on processing traumatic memories, Eric Vermetten, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

He and his colleagues have developed an innovative approach to delivering trauma-focused psychotherapy. They call it Multimodular Motion-Assisted Memory Desensitization and Reconsolidation (3MDR), or more informally, “walk and talk therapy,” explained Dr. Vermetten, professor of psychiatry at Leiden (the Netherlands) University and a military mental health researcher for the Dutch Ministry of Defense.

3MDR is a combination of personalized virtual reality using a headset, multisensory input using self-selected trauma-related pictures, and a dual-attention task borrowed from eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, with treadmill walking throughout the treatment session.

3MDR is designed to boost this process of memory retrieval and reconsolidation by creating a more totally immersive patient experience intended to enhance treatment engagement and overcome behavioral avoidance. Through virtual reality, the PTSD patient literally walks toward his personal fear-related images.

Dr. Vermetten and his coinvestigators came up with 3MDR as a treatment designed for military veterans with chronic, combat-related, treatment-resistant PTSD. The impetus was the evident need for new and better forms of psychotherapy for such patients. Even though an array of evidence-based psychotherapies are available as guideline-recommended first-line treatments for PTSD, individuals with combat-related PTSD have a notoriously low response rate to these interventions, presumably because of the intensity and repetitive nature of their traumatic experiences. Indeed, up to two-thirds of veterans with PTSD experience substantial residual symptoms post treatment such that they still meet diagnostic criteria for the disorder.

3MDR is an amped up form of exposure-based therapy in which patients walk through a personalized virtual reality installation toward self-chosen trauma-related pictures of their deployment. The investigators developed this intensely immersive type of psychotherapy because they believe avoidance and lack of emotional engagement figure prominently in the low success rate of established forms of psychotherapy in combat-related PTSD. The treadmill walking aspect is considered key because of the large body of research showing that walking entails cognitive-motor interactions that facilitate problem solving, the psychiatrist explained.

The investigators recently published a detailed description of the therapeutic rationale for 3MDR and the nuts and bolts of the novel therapy (Front Psychiatry. 2018 May 4;9:176. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00176). Early anecdotal experience has been positive. However, as cochair of the ECNP Traumatic Stress Network, Dr. Vermetten is acutely aware of the need to demonstrate efficacy in rigorous randomized controlled trials.

“This is a way psychotherapy can be shaped in the future. We’re collaborating with various centers across the globe now to see whether this is effective for treatment-resistant PTSD patients,” Dr. Vermetten said.

If those studies prove positive, it will be worthwhile to determine whether 3MDR also has a role as a first-line treatment for earlier-stage PTSD and for forms of the disorder unrelated to military combat, he added.

Funding for the project has been provided by the Dutch Ministry of Defense.

BARCELONA – The therapeutic setting for individual psychotherapy has shifted over the years from the analytic couch, with the therapist discretely tucked out of sight, to facing chairs, a similarly sedentary format. The next evolutionary development might be to plop a patient with posttraumatic stress disorder on an exercise treadmill and don a virtual reality helmet to engage in an interactive motion-assisted form of psychotherapy in which the therapist stands alongside the walking patient while providing guidance on processing traumatic memories, Eric Vermetten, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

He and his colleagues have developed an innovative approach to delivering trauma-focused psychotherapy. They call it Multimodular Motion-Assisted Memory Desensitization and Reconsolidation (3MDR), or more informally, “walk and talk therapy,” explained Dr. Vermetten, professor of psychiatry at Leiden (the Netherlands) University and a military mental health researcher for the Dutch Ministry of Defense.

3MDR is a combination of personalized virtual reality using a headset, multisensory input using self-selected trauma-related pictures, and a dual-attention task borrowed from eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, with treadmill walking throughout the treatment session.

3MDR is designed to boost this process of memory retrieval and reconsolidation by creating a more totally immersive patient experience intended to enhance treatment engagement and overcome behavioral avoidance. Through virtual reality, the PTSD patient literally walks toward his personal fear-related images.

Dr. Vermetten and his coinvestigators came up with 3MDR as a treatment designed for military veterans with chronic, combat-related, treatment-resistant PTSD. The impetus was the evident need for new and better forms of psychotherapy for such patients. Even though an array of evidence-based psychotherapies are available as guideline-recommended first-line treatments for PTSD, individuals with combat-related PTSD have a notoriously low response rate to these interventions, presumably because of the intensity and repetitive nature of their traumatic experiences. Indeed, up to two-thirds of veterans with PTSD experience substantial residual symptoms post treatment such that they still meet diagnostic criteria for the disorder.

3MDR is an amped up form of exposure-based therapy in which patients walk through a personalized virtual reality installation toward self-chosen trauma-related pictures of their deployment. The investigators developed this intensely immersive type of psychotherapy because they believe avoidance and lack of emotional engagement figure prominently in the low success rate of established forms of psychotherapy in combat-related PTSD. The treadmill walking aspect is considered key because of the large body of research showing that walking entails cognitive-motor interactions that facilitate problem solving, the psychiatrist explained.

The investigators recently published a detailed description of the therapeutic rationale for 3MDR and the nuts and bolts of the novel therapy (Front Psychiatry. 2018 May 4;9:176. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00176). Early anecdotal experience has been positive. However, as cochair of the ECNP Traumatic Stress Network, Dr. Vermetten is acutely aware of the need to demonstrate efficacy in rigorous randomized controlled trials.

“This is a way psychotherapy can be shaped in the future. We’re collaborating with various centers across the globe now to see whether this is effective for treatment-resistant PTSD patients,” Dr. Vermetten said.

If those studies prove positive, it will be worthwhile to determine whether 3MDR also has a role as a first-line treatment for earlier-stage PTSD and for forms of the disorder unrelated to military combat, he added.

Funding for the project has been provided by the Dutch Ministry of Defense.

REPORTING FROM THE ECNP CONGRESS

New PTSD prevention guidelines released

Hydrocortisone is only drug rated as an ‘intervention with emerging evidence of efficacy’

Barcelona – New evidence-based guidelines on posttraumatic stress disorder prevention and treatment from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) highlight an uncomfortable truth: Namely, the basis for early formal intervention of any sort is sorely lacking.

“I’m acutely aware that a lot of people in the mental health field are not aware of the evidence base as it stands at the moment,” Jonathan I. Bisson, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. “There’s something very human about trying to do something. I think we find it very hard to do nothing following a traumatic event.”

Dr. Bisson, a professor of psychiatry at Cardiff (Wales) University and the chair of the ISTSS guidelines committee, provided an advance look at the ISTSS guidelines, which have since been released.

Secondary prevention of PTSD can entail either blocking development of symptoms after exposure to trauma or treating early emergent PTSD symptoms. Dr. Bisson emphasized that, although multiple exciting prospects are on the horizon for secondary prevention, those interventions need further work before implementation. The ISTSS guidelines, based on the group’s meta-analyses of 361 randomized controlled trials, rated most of the diverse psychosocial, psychological, and pharmacologic interventions that have been proposed or are now actually being used in clinical practice as either “low effect,” “interventions with emerging evidence,” or “insufficient evidence to recommend.” Those interventions are not backed by sufficient evidence of efficacy to be ready for prime time use in clinical practice.

Morever, the potential for iatrogenic harm is very real.

to a trauma,” the psychiatrist observed. “It’s normal to cry after a bereavement, for example. But should we be pathologizing that, or is that the body’s way of actually bringing itself to terms with something that’s very extreme?

“So we’ve got to be careful in our efforts to shape emotional processing, which might do absolutely nothing – which I’d argue is a problem when we’ve got limited resources because we should be focusing those resources on things that make a difference. Or it could minimize or prevent prolonged distress or pathology, which is what we’re after. Or it could interfere with the adaptive acute stress response – and that’s a real problem and one we’ve got to be very careful about,” Dr. Bisson said. “So ‘primum non nocere’ – first do no harm – should be a principle we adhere to.”

Neurobiology of PTSD

The accepted view of the neurobiology of PTSD is that it represents a failure of the medial prefrontal/anterior cingulate network to regulate activity in the amygdala, with resultant hyperreactivity to threat. Enhanced negative feedback of cortisol occurs. The brain’s response to low cortisol is to increase levels of corticotropin-releasing factor, which has the unwanted consequence of increased locus coeruleus activity and noradrenaline release. The resultant adrenergic surge facilitates the laying down and consolidation of traumatic memories.

Also, low cortisol levels disinhibit retrieval of traumatic memories, so the affected individual thinks more about the trauma. All of this elicits an uncontrolled sympathetic response, so the patient remains in a constant state of hyperarousal characteristic of PTSD.

“In theory we should have some really simple ways to prevent PTSD from occurring if we get in there soon enough: reducing noradrenergic overactivity via alpha2-adrenergic receptor agonism with an agent such as clonidine; postsynaptic beta-adrenergic blocking with a drug such as propranolol; or alpha1-adrenergic receptor blocking, as with prazosin. All of these approaches reduce noradrenergic tone and therefore should be effective, in theory, to prevent PTSD.

“We should also be able to use indirect strategies to reduce noradrenergic overactivity: GABA agents like benzodiazepines, alcohol, and gabapentin oppose noradrenaline action in the amygdala. I’m not suggesting drinking all the time to prevent PTSD, but there’s a strong association in several studies, with about a 50% reduction in rates of PTSD in those who are intoxicated at the time of the trauma,” according to Dr. Bisson.

Unfortunately, to date, none of those pharmacologic approaches have been effective when studied in randomized trials.

One pharmacologic intervention

Only one drug, hydrocortisone, was rated an “intervention with emerging evidence of efficacy” for prevention of PTSD symptoms in adults when given within the first 3 months after a traumatic event. Three placebo-controlled, randomized trials have shown a positive effect.

“It should be said that most of the studies of hydrocortisone have been done in individuals following extreme physical illness, such as septic shock sufferers, so the generalizability is a bit of a question. Nevertheless, it’s the one agent that has meta-analytic evidence of being effective at preventing PTSD, although more research is needed,” Dr. Bisson said.

Results of randomized trials featuring those agents have been “really disappointing” in light of what seems a sound theoretic rationale, he continued.

“We’re really struggling from a pharmacologic perspective to know what to do. I would say we are still at the experimental stage, and there’s no real good evidence that we should give any medication to prevent PTSD,” Dr. Bisson said.

Early psychosocial interventions

The ISTSS guidelines rate only two single-session interventions for prevention as rising to the promising level of “emerging evidence” of clinically important benefit: single-session eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), which in its multisession format is a well-established treatment with strong evidence of efficacy in established PTSD, and a program known as Group 512 PM, which combines group debriefing with group cohesion–building exercises.

“Group 512 PM was done in groups of Chinese army personnel helping in recovery efforts following a 2008 earthquake in China that killed 80,000 people. It resulted in nearly a 50% reduction in PTSD versus no debriefing. This cohesion training might be a clue to us as something to work on in the future,” Dr. Bisson said.

The ISTSS guidelines deem there is insufficient evidence to recommend single-session group debriefing, group stress management, heart stress management, group education, trauma-focused counselling, computerized visuospatial task, individual psychoeducation, or individual debriefing.

“In six randomized controlled trials over nearly the last 20 years, we see a strong signal that individual psychological debriefing isn’t effective. So, certainly, going into a room with an individual or a couple and talking about what they’ve been through in great detail and getting them to express their emotions and advising them that’s a normal reaction doesn’t seem to be enough. And rather worryingly, the people who tend to do worse with that sort of intervention are the people who’ve got the most symptoms when they started, so they’re the ones at highest risk of developing PTSD,” Dr. Bisson said.

Multisession prevention interventions such as brief dyadic therapy and self-guided Internet interventions are supported by emerging evidence. Less promising, and with insufficient evidence to recommend, according to the ISTSS, are brief interpersonal therapy, brief individual trauma processing therapy, telephone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and nurse-led intensive care recovery programs.

For multisession early treatment interventions for patients with emerging traumatic stress symptoms within the first 3 months, the new ISTSS guidelines recommend as standard therapy CBT with a trauma focus, EMDR, or cognitive therapy. Stepped or collaborative care is rated as having “low effect.” There is emerging evidence for structured writing interventions and Internet-based guided self-help. And there is insufficient evidence to recommend behavioral activation, Internet virtual reality therapy, telephone-based CBT with a trauma focus, computerized neurobehavioral training, or supportive counseling.

Treating adults with established PTSD

Pharmacotherapy, including fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, and venlafaxine is rated in the guidelines as a low-effect treatment. Quetiapine has emerging evidence of efficacy. Everything else has insufficient evidence.

Psychological therapies such as EMDR, CBT with a trauma focus, prolonged exposure, cognitive therapy, and cognitive processing therapy received strong recommendations. In fact, those are the only interventions in the entire ISTSS guidelines that received a “strong recommendation” rating. A weaker “standard recommendation” is given to CBT without a trauma focus, narrative exposure therapy, present-centered therapy, group CBT with a trauma focus, and guided Internet-based therapy with a trauma focus. Interventions with emerging evidence of efficacy include virtual reality therapy, reconsolidation of traumatic memories, and couples CBT with a trauma focus.

Best-practice approach to prevention

“In my view, and what I tell people, is that after a traumatic event I think practical pragmatic support in an empathic manner is the best first step,” Dr. Bisson said. “And it doesn’t have to be provided by a mental health professional. In fact, your family and friends are the best people to provide that. And then, we watchfully wait to see if traumatic stress symptoms emerge. If they do, and particularly if their trajectory is going up, then at about 1 month, I would get in there and deliver a therapy, either CBT with a trauma focus, EMDR, or cognitive therapy with a trauma focus. All of those have a significant positive effect for this group.”

Although he restricted his talk to secondary prevention of PTSD in adults, the ISTSS guidelines also address early intervention in children and adolescents.

Dr. Bisson reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

Hydrocortisone is only drug rated as an ‘intervention with emerging evidence of efficacy’

Hydrocortisone is only drug rated as an ‘intervention with emerging evidence of efficacy’

Barcelona – New evidence-based guidelines on posttraumatic stress disorder prevention and treatment from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) highlight an uncomfortable truth: Namely, the basis for early formal intervention of any sort is sorely lacking.

“I’m acutely aware that a lot of people in the mental health field are not aware of the evidence base as it stands at the moment,” Jonathan I. Bisson, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. “There’s something very human about trying to do something. I think we find it very hard to do nothing following a traumatic event.”

Dr. Bisson, a professor of psychiatry at Cardiff (Wales) University and the chair of the ISTSS guidelines committee, provided an advance look at the ISTSS guidelines, which have since been released.

Secondary prevention of PTSD can entail either blocking development of symptoms after exposure to trauma or treating early emergent PTSD symptoms. Dr. Bisson emphasized that, although multiple exciting prospects are on the horizon for secondary prevention, those interventions need further work before implementation. The ISTSS guidelines, based on the group’s meta-analyses of 361 randomized controlled trials, rated most of the diverse psychosocial, psychological, and pharmacologic interventions that have been proposed or are now actually being used in clinical practice as either “low effect,” “interventions with emerging evidence,” or “insufficient evidence to recommend.” Those interventions are not backed by sufficient evidence of efficacy to be ready for prime time use in clinical practice.

Morever, the potential for iatrogenic harm is very real.

to a trauma,” the psychiatrist observed. “It’s normal to cry after a bereavement, for example. But should we be pathologizing that, or is that the body’s way of actually bringing itself to terms with something that’s very extreme?

“So we’ve got to be careful in our efforts to shape emotional processing, which might do absolutely nothing – which I’d argue is a problem when we’ve got limited resources because we should be focusing those resources on things that make a difference. Or it could minimize or prevent prolonged distress or pathology, which is what we’re after. Or it could interfere with the adaptive acute stress response – and that’s a real problem and one we’ve got to be very careful about,” Dr. Bisson said. “So ‘primum non nocere’ – first do no harm – should be a principle we adhere to.”

Neurobiology of PTSD

The accepted view of the neurobiology of PTSD is that it represents a failure of the medial prefrontal/anterior cingulate network to regulate activity in the amygdala, with resultant hyperreactivity to threat. Enhanced negative feedback of cortisol occurs. The brain’s response to low cortisol is to increase levels of corticotropin-releasing factor, which has the unwanted consequence of increased locus coeruleus activity and noradrenaline release. The resultant adrenergic surge facilitates the laying down and consolidation of traumatic memories.

Also, low cortisol levels disinhibit retrieval of traumatic memories, so the affected individual thinks more about the trauma. All of this elicits an uncontrolled sympathetic response, so the patient remains in a constant state of hyperarousal characteristic of PTSD.

“In theory we should have some really simple ways to prevent PTSD from occurring if we get in there soon enough: reducing noradrenergic overactivity via alpha2-adrenergic receptor agonism with an agent such as clonidine; postsynaptic beta-adrenergic blocking with a drug such as propranolol; or alpha1-adrenergic receptor blocking, as with prazosin. All of these approaches reduce noradrenergic tone and therefore should be effective, in theory, to prevent PTSD.

“We should also be able to use indirect strategies to reduce noradrenergic overactivity: GABA agents like benzodiazepines, alcohol, and gabapentin oppose noradrenaline action in the amygdala. I’m not suggesting drinking all the time to prevent PTSD, but there’s a strong association in several studies, with about a 50% reduction in rates of PTSD in those who are intoxicated at the time of the trauma,” according to Dr. Bisson.

Unfortunately, to date, none of those pharmacologic approaches have been effective when studied in randomized trials.

One pharmacologic intervention

Only one drug, hydrocortisone, was rated an “intervention with emerging evidence of efficacy” for prevention of PTSD symptoms in adults when given within the first 3 months after a traumatic event. Three placebo-controlled, randomized trials have shown a positive effect.

“It should be said that most of the studies of hydrocortisone have been done in individuals following extreme physical illness, such as septic shock sufferers, so the generalizability is a bit of a question. Nevertheless, it’s the one agent that has meta-analytic evidence of being effective at preventing PTSD, although more research is needed,” Dr. Bisson said.

Results of randomized trials featuring those agents have been “really disappointing” in light of what seems a sound theoretic rationale, he continued.

“We’re really struggling from a pharmacologic perspective to know what to do. I would say we are still at the experimental stage, and there’s no real good evidence that we should give any medication to prevent PTSD,” Dr. Bisson said.

Early psychosocial interventions

The ISTSS guidelines rate only two single-session interventions for prevention as rising to the promising level of “emerging evidence” of clinically important benefit: single-session eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), which in its multisession format is a well-established treatment with strong evidence of efficacy in established PTSD, and a program known as Group 512 PM, which combines group debriefing with group cohesion–building exercises.

“Group 512 PM was done in groups of Chinese army personnel helping in recovery efforts following a 2008 earthquake in China that killed 80,000 people. It resulted in nearly a 50% reduction in PTSD versus no debriefing. This cohesion training might be a clue to us as something to work on in the future,” Dr. Bisson said.

The ISTSS guidelines deem there is insufficient evidence to recommend single-session group debriefing, group stress management, heart stress management, group education, trauma-focused counselling, computerized visuospatial task, individual psychoeducation, or individual debriefing.

“In six randomized controlled trials over nearly the last 20 years, we see a strong signal that individual psychological debriefing isn’t effective. So, certainly, going into a room with an individual or a couple and talking about what they’ve been through in great detail and getting them to express their emotions and advising them that’s a normal reaction doesn’t seem to be enough. And rather worryingly, the people who tend to do worse with that sort of intervention are the people who’ve got the most symptoms when they started, so they’re the ones at highest risk of developing PTSD,” Dr. Bisson said.

Multisession prevention interventions such as brief dyadic therapy and self-guided Internet interventions are supported by emerging evidence. Less promising, and with insufficient evidence to recommend, according to the ISTSS, are brief interpersonal therapy, brief individual trauma processing therapy, telephone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and nurse-led intensive care recovery programs.

For multisession early treatment interventions for patients with emerging traumatic stress symptoms within the first 3 months, the new ISTSS guidelines recommend as standard therapy CBT with a trauma focus, EMDR, or cognitive therapy. Stepped or collaborative care is rated as having “low effect.” There is emerging evidence for structured writing interventions and Internet-based guided self-help. And there is insufficient evidence to recommend behavioral activation, Internet virtual reality therapy, telephone-based CBT with a trauma focus, computerized neurobehavioral training, or supportive counseling.

Treating adults with established PTSD

Pharmacotherapy, including fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, and venlafaxine is rated in the guidelines as a low-effect treatment. Quetiapine has emerging evidence of efficacy. Everything else has insufficient evidence.

Psychological therapies such as EMDR, CBT with a trauma focus, prolonged exposure, cognitive therapy, and cognitive processing therapy received strong recommendations. In fact, those are the only interventions in the entire ISTSS guidelines that received a “strong recommendation” rating. A weaker “standard recommendation” is given to CBT without a trauma focus, narrative exposure therapy, present-centered therapy, group CBT with a trauma focus, and guided Internet-based therapy with a trauma focus. Interventions with emerging evidence of efficacy include virtual reality therapy, reconsolidation of traumatic memories, and couples CBT with a trauma focus.

Best-practice approach to prevention

“In my view, and what I tell people, is that after a traumatic event I think practical pragmatic support in an empathic manner is the best first step,” Dr. Bisson said. “And it doesn’t have to be provided by a mental health professional. In fact, your family and friends are the best people to provide that. And then, we watchfully wait to see if traumatic stress symptoms emerge. If they do, and particularly if their trajectory is going up, then at about 1 month, I would get in there and deliver a therapy, either CBT with a trauma focus, EMDR, or cognitive therapy with a trauma focus. All of those have a significant positive effect for this group.”

Although he restricted his talk to secondary prevention of PTSD in adults, the ISTSS guidelines also address early intervention in children and adolescents.

Dr. Bisson reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

Barcelona – New evidence-based guidelines on posttraumatic stress disorder prevention and treatment from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) highlight an uncomfortable truth: Namely, the basis for early formal intervention of any sort is sorely lacking.

“I’m acutely aware that a lot of people in the mental health field are not aware of the evidence base as it stands at the moment,” Jonathan I. Bisson, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. “There’s something very human about trying to do something. I think we find it very hard to do nothing following a traumatic event.”

Dr. Bisson, a professor of psychiatry at Cardiff (Wales) University and the chair of the ISTSS guidelines committee, provided an advance look at the ISTSS guidelines, which have since been released.

Secondary prevention of PTSD can entail either blocking development of symptoms after exposure to trauma or treating early emergent PTSD symptoms. Dr. Bisson emphasized that, although multiple exciting prospects are on the horizon for secondary prevention, those interventions need further work before implementation. The ISTSS guidelines, based on the group’s meta-analyses of 361 randomized controlled trials, rated most of the diverse psychosocial, psychological, and pharmacologic interventions that have been proposed or are now actually being used in clinical practice as either “low effect,” “interventions with emerging evidence,” or “insufficient evidence to recommend.” Those interventions are not backed by sufficient evidence of efficacy to be ready for prime time use in clinical practice.

Morever, the potential for iatrogenic harm is very real.

to a trauma,” the psychiatrist observed. “It’s normal to cry after a bereavement, for example. But should we be pathologizing that, or is that the body’s way of actually bringing itself to terms with something that’s very extreme?

“So we’ve got to be careful in our efforts to shape emotional processing, which might do absolutely nothing – which I’d argue is a problem when we’ve got limited resources because we should be focusing those resources on things that make a difference. Or it could minimize or prevent prolonged distress or pathology, which is what we’re after. Or it could interfere with the adaptive acute stress response – and that’s a real problem and one we’ve got to be very careful about,” Dr. Bisson said. “So ‘primum non nocere’ – first do no harm – should be a principle we adhere to.”

Neurobiology of PTSD

The accepted view of the neurobiology of PTSD is that it represents a failure of the medial prefrontal/anterior cingulate network to regulate activity in the amygdala, with resultant hyperreactivity to threat. Enhanced negative feedback of cortisol occurs. The brain’s response to low cortisol is to increase levels of corticotropin-releasing factor, which has the unwanted consequence of increased locus coeruleus activity and noradrenaline release. The resultant adrenergic surge facilitates the laying down and consolidation of traumatic memories.

Also, low cortisol levels disinhibit retrieval of traumatic memories, so the affected individual thinks more about the trauma. All of this elicits an uncontrolled sympathetic response, so the patient remains in a constant state of hyperarousal characteristic of PTSD.

“In theory we should have some really simple ways to prevent PTSD from occurring if we get in there soon enough: reducing noradrenergic overactivity via alpha2-adrenergic receptor agonism with an agent such as clonidine; postsynaptic beta-adrenergic blocking with a drug such as propranolol; or alpha1-adrenergic receptor blocking, as with prazosin. All of these approaches reduce noradrenergic tone and therefore should be effective, in theory, to prevent PTSD.

“We should also be able to use indirect strategies to reduce noradrenergic overactivity: GABA agents like benzodiazepines, alcohol, and gabapentin oppose noradrenaline action in the amygdala. I’m not suggesting drinking all the time to prevent PTSD, but there’s a strong association in several studies, with about a 50% reduction in rates of PTSD in those who are intoxicated at the time of the trauma,” according to Dr. Bisson.

Unfortunately, to date, none of those pharmacologic approaches have been effective when studied in randomized trials.

One pharmacologic intervention

Only one drug, hydrocortisone, was rated an “intervention with emerging evidence of efficacy” for prevention of PTSD symptoms in adults when given within the first 3 months after a traumatic event. Three placebo-controlled, randomized trials have shown a positive effect.

“It should be said that most of the studies of hydrocortisone have been done in individuals following extreme physical illness, such as septic shock sufferers, so the generalizability is a bit of a question. Nevertheless, it’s the one agent that has meta-analytic evidence of being effective at preventing PTSD, although more research is needed,” Dr. Bisson said.

Results of randomized trials featuring those agents have been “really disappointing” in light of what seems a sound theoretic rationale, he continued.

“We’re really struggling from a pharmacologic perspective to know what to do. I would say we are still at the experimental stage, and there’s no real good evidence that we should give any medication to prevent PTSD,” Dr. Bisson said.

Early psychosocial interventions

The ISTSS guidelines rate only two single-session interventions for prevention as rising to the promising level of “emerging evidence” of clinically important benefit: single-session eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), which in its multisession format is a well-established treatment with strong evidence of efficacy in established PTSD, and a program known as Group 512 PM, which combines group debriefing with group cohesion–building exercises.

“Group 512 PM was done in groups of Chinese army personnel helping in recovery efforts following a 2008 earthquake in China that killed 80,000 people. It resulted in nearly a 50% reduction in PTSD versus no debriefing. This cohesion training might be a clue to us as something to work on in the future,” Dr. Bisson said.

The ISTSS guidelines deem there is insufficient evidence to recommend single-session group debriefing, group stress management, heart stress management, group education, trauma-focused counselling, computerized visuospatial task, individual psychoeducation, or individual debriefing.

“In six randomized controlled trials over nearly the last 20 years, we see a strong signal that individual psychological debriefing isn’t effective. So, certainly, going into a room with an individual or a couple and talking about what they’ve been through in great detail and getting them to express their emotions and advising them that’s a normal reaction doesn’t seem to be enough. And rather worryingly, the people who tend to do worse with that sort of intervention are the people who’ve got the most symptoms when they started, so they’re the ones at highest risk of developing PTSD,” Dr. Bisson said.

Multisession prevention interventions such as brief dyadic therapy and self-guided Internet interventions are supported by emerging evidence. Less promising, and with insufficient evidence to recommend, according to the ISTSS, are brief interpersonal therapy, brief individual trauma processing therapy, telephone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and nurse-led intensive care recovery programs.