Opioids were involved in 42,249 deaths in the United States in 2016, and opioid overdoses have quintupled since 1999.1 Among the causes behind these statistics is increased opiate prescribing by physicians—with primary care providers accounting for about one half of opiate prescriptions.2 As a result, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a 4-part response for physicians,3 which includes careful opiate prescribing, expanded access to naloxone, prevention of opioid use disorder (OUD), and expanded use of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of addiction—with the goal of preventing and managing OUD.

CASE

Fred R, a 55-year-old man who has been taking oxycodone, 70 mg/d, for chronic pain for longer than 10 years, visits your clinic for a prescription refill. His prescription monitoring program confirms the long history of regular oxycodone use, with the dosage escalating over the past 6 months. He recently was discharged from the hospital after an overdose of opiates.

Mr. R admits to using heroin after running out of oxycodone. He is in mild withdrawal, with a score of 8 (of a possible 48) on the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale4 (COWS, which assigns point values to 11 common symptoms to gauge the severity of opioid withdrawal and, by inference, the patient’s degree of physical dependence). You determine that Mr. R is frightened about his use of oxycodone and would like to stop; he has tried to stop several times on his own but always relapses when withdrawal becomes severe.

How would you proceed with the care of this patient?

What is OUD? How is the diagnosis made?

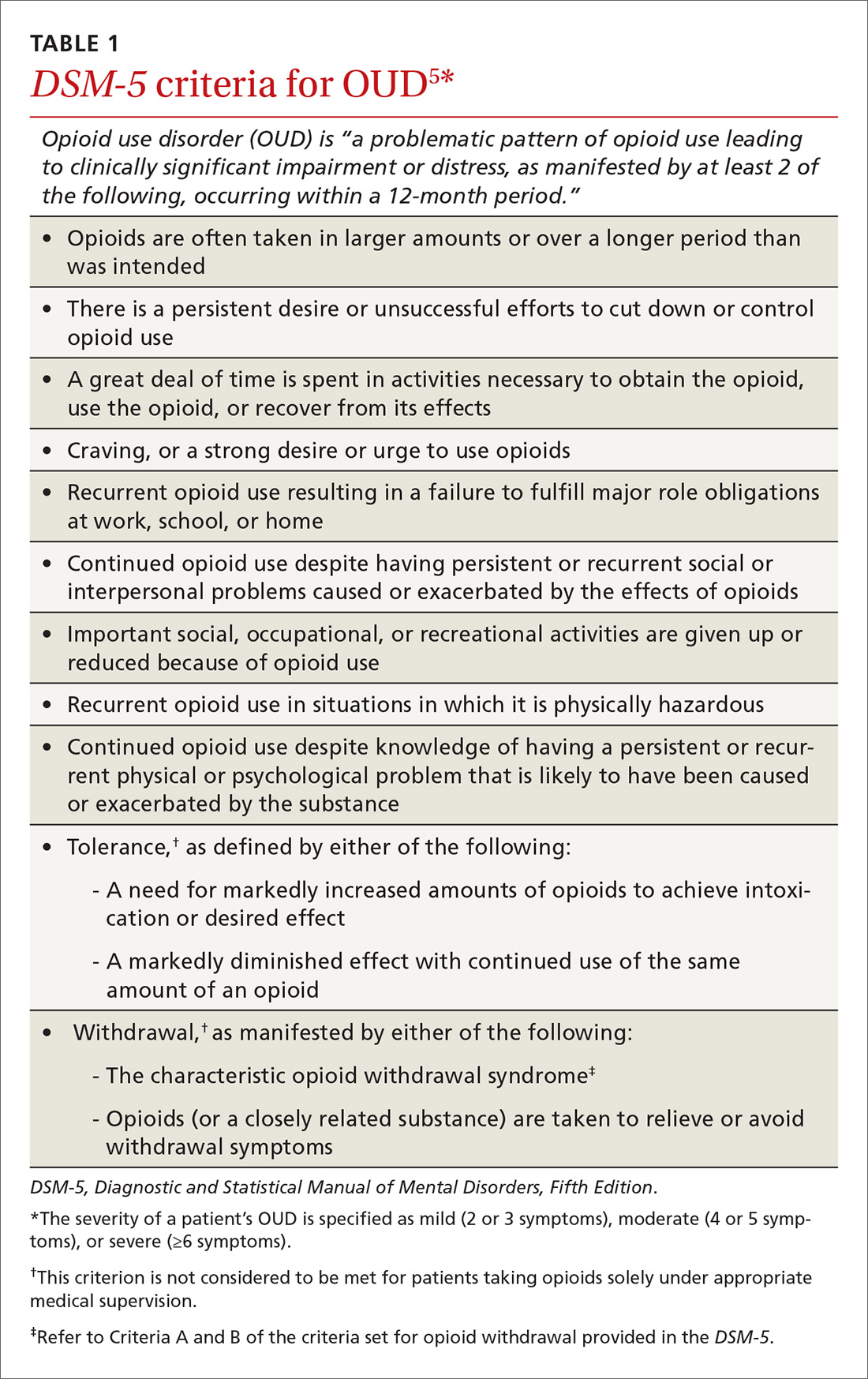

OUD is a combination of cognitive, behavioral, and physiologic symptoms arising from continued use of opioids despite significant health, legal, or relationship problems related to their use. The disorder is diagnosed based on specific criteria provided in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)(TABLE 1)5 and is revealed by 1) a careful history that delineates a problematic pattern of opioid use, 2) physical examination, and 3) urine toxicology screen.

Identification of acute opioid intoxication can also be useful when working up a patient in whom OUD is suspected; findings of acute opioid intoxication on physical examination include constricted pupils, head-nodding, excessive sleepiness, and drooping eyelids. Other physical signs of illicit opioid use include track marks around veins of the arm, evidence of repeated trauma, and stigmata of liver dysfunction. Withdrawal can present as agitation, rhinorrhea, dilated pupils, nausea, diarrhea, yawning, and gooseflesh. The COWS, which, as noted in the case, assigns point values to withdrawal symptoms, can be helpful in determining the severity of withdrawal.4

What is the differential Dx of OUD?

When OUD is likely, but not clearly diagnosable, on the basis of findings, consider a mental health disorder: depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder, personality disorder, and polysubstance use disorder. Concurrent diagnosis of substance abuse and a mental health disorder is common; treatment requires that both disorders be addressed simultaneously.6 Assessing for use or abuse of, and addiction to, other substances is vital to ensure proper diagnosis and effective therapy. Polysubstance dependence can be more difficult to treat than single-substance abuse or addiction alone.

Continue to: How is OUD treated?