Practice Gap

Nonmelanoma skin cancer is the most common cancer, typically growing in sun-exposed areas. As such, the nasal area is a common site of onset, constituting approximately 25% of cases. Surgical excision of these cancers generally has a high cure rate.1

Although complete excision of the tumor is the primary goal of the dermatologic surgeon, achieving a cosmetically satisfactory scar also is important. As a prominent feature of the face, any irregularities to the nose are easily noticeable.2 The subsequent scar may exhibit features that are less than ideal and cause notable stress to the patient.

When a scar presents with several complications, using a single surgical technique may not sufficiently address all defects. As a result, it can be challenging for the surgeon to decide which combination of methods among the myriad of nonsurgical and surgical options for scar revision will produce the best cosmetic outcome.

Case and Technique

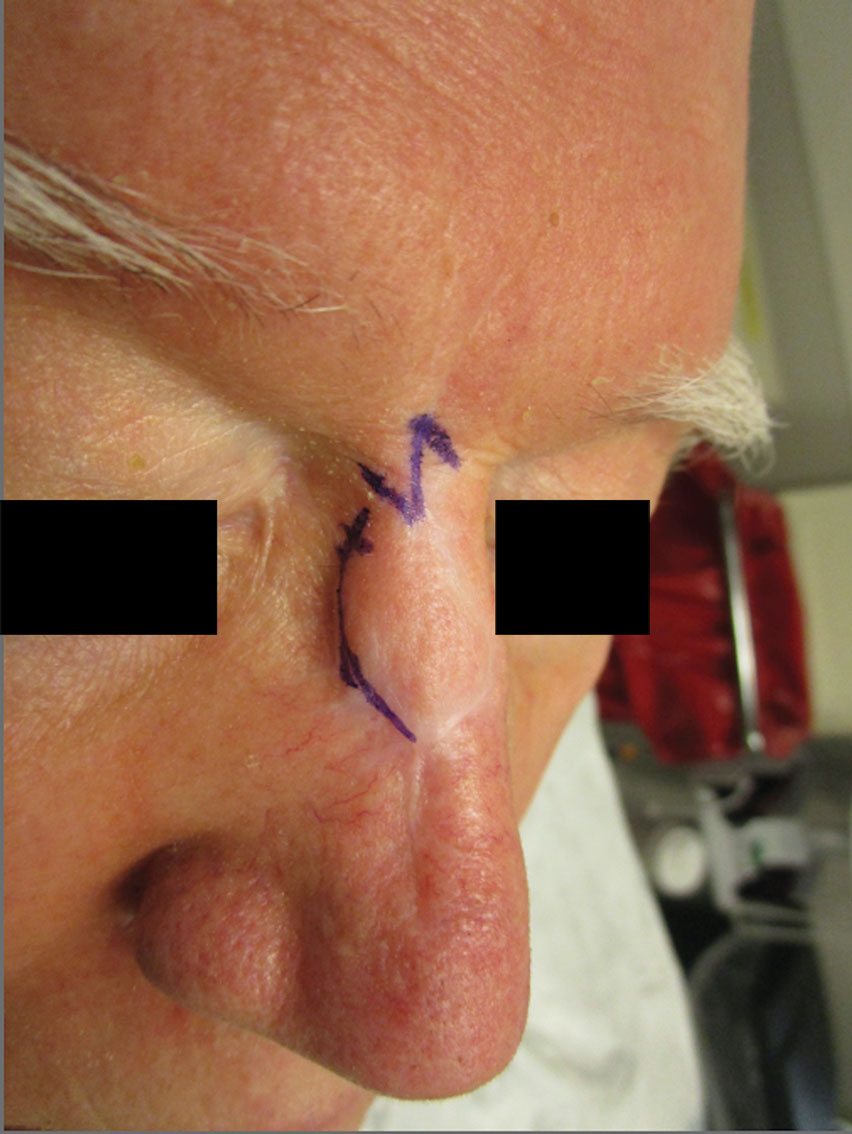

A 76-year-old man presented 1 year after he underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for squamous cell carcinoma on the nasal dorsum. The tumor cleared after 1 stage and was repaired using a bilateral V-Y advancement flap. Postoperatively, the patient developed pincushioning of the flap, atrophic scarring inferior to the flap, and webbing of the pivotal restraint point at the nasal root (Figures 1A and 1B). We opted to address the pincushioning and nasal root webbing by defatting the flap and performing Z-plasty, respectively.

Pincushioning—Pincushioning of a flap arises due to contraction and lymphedema at the edge of the repair. It is seen more often in nasal repairs due to the limited availability of surrounding skin and changes in skin texture from rhinion to tip.3 To combat this in our patient, an incision was made around the site of the original flap, surrounding tissue was undermined, and the flap was reflected back. Subcutaneous tissue was removed with scissors. The flap was then laid back into the defect, and the subcutaneous tissue and dermis were closed with interrupted buried vertical mattress sutures. The epidermis was closed in a simple running fashion.

Webbing—Webbing of a scar also may develop from the contractile wound-healing process.4 Z-plasty commonly is used to camouflage a linear or contracted scar, increase skin availability in an area, or alter scar direction to better align with skin-tension lines.5,6 In our patient, we incised the webbing of the nasal root along the vertical scar. Two arms were drawn at each end of the scar at a 60° angle (Figure 2); the side arms were drawn equal in length and incised vertically. Full-thickness skin flaps were then undermined at the level of subcutaneous fat, creating 2 triangular flaps. Adequate undermining of the surrounding subcutaneous tissue was performed to achieve proper mobilization of the flaps, which allowed for flap transposition to occur without tension and therefore for proper redirection of the scar.6 The flaps were secured using buried vertical mattress sutures and simple running sutures. Using too many buried interrupted sutures can cause vascular compromise of the fragile tips of the Z and should be avoided.3

At 4-month postoperative follow-up, the cosmetic outcome was judged satisfactory (Figure 1C).