CASE Pregnant woman with a suspected parasitic infection

A 20-year-old, previously healthy, primigravid woman at 24 weeks’ gestation immigrated from Bolivia to the United States 3 days ago. On the morning of her international flight, she awoke to discover a small insect bite just below her left eye. She sought medical evaluation because her eyelid is now significantly swollen, and she has a headache, anorexia, fatigue, and a fever of 38.4° C. The examining physician ordered a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for Trypanosoma cruzi, and the test is positive.

- How should this patient be treated during, and after, her delivery?

- Does this infection pose a risk to the newborn baby?

- What type of surveillance and treatment is indicated for the baby?

Chagas disease is common in South America, Central America, and Mexico and is well known to physicians in those countries. Clinicians who practice in the United States are much less familiar with the condition, but it is becoming increasingly common as a result of international travel within the Americas.

In this article, we review the interesting microbiology and epidemiology of Chagas disease, focus on its clinical manifestations, and discuss the most useful diagnostic tests for the illness. We conclude with a summary of preventive and treatment measures, with particular emphasis on managing the disease in pregnancy.

How Chagas disease is transmitted and who is at risk

Chagas disease was named in honor of a Brazilian physician, Carlos Chagas, who first described the condition in 1909. The disease is endemic in South America, Central America, and Mexico, and, recently, its prevalence has increased in the southern United States. Approximately 300,000 people in the United States are infected.1,2

The illness is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, and it is also known as American trypanosomiasis. The parasite is spread primarily by the bite of triatomine insects (“kissing bugs”). Approximately 60% of these insects are infected with the parasite. The insects live and thrive in the interspaces of mud walls (adobe homes) and thatched roofs. At night, the insects leave their darkened spaces and feed on the exposed skin of sleeping persons. They are particularly likely to bite the moist skin surfaces near the eye and mouth, and, as they do, they defecate and excrete the parasite into the blood vessels beneath the skin. Within the blood, the trypomastigotes invade various host cells. Inside the host cells, the organism transforms into an amastigote, which is the replicative form of the parasite. After several rounds of replication, the amastigote transforms back into a trypomastigote, bursts from the cell, and goes on to infect other host cells.1

In addition to transmission by the insect vector, the parasite also can be transmitted by blood transfusion and organ donation. When contaminated blood is transfused, the risk of transmission is approximately 10% to 25% for each unit. Following implementation of effective screening programs by blood banks in Central America, South America, Mexico, and the United States, the risk of transmission from undetected infection is now approximately 1:200,000 per unit.

When a transplant procedure with an infected heart is performed, the risk of transmission is 75% to 100%. For liver transplants, the frequency of transmission is 0% to 29%; for kidney transplants, the risk of transmission is 0% to 19%.

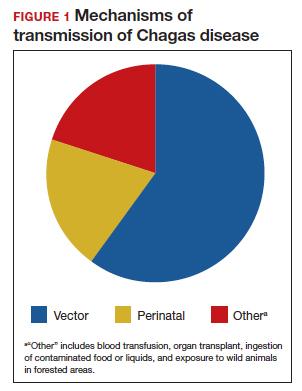

Consumption of contaminated food or drink, particularly nonpasteurized items sold by street vendors, is also an important mechanism of transmission. In addition, transmission can occur as a result of laboratory exposure and by exposure to wild animals (racoons, opossums, marmosets, bats, armadillos) in forested areas. Finally, perinatal transmission now accounts for about 22% of infections. As effective vector control programs have been introduced in endemic areas, the proportion of cases caused by the insect vector has steadily decreased1-3 (FIGURE 1).

Continue to: Clinical manifestations of Chagas disease...