The lowest available national prices of drugs to treat obesity are up to 20 times higher than the estimated cost of profitable generic versions of the same agents, according to a new analysis.

The findings by Jacob Levi, MBBS, and colleagues were published in Obesity.

“Our study highlights the inequality in pricing that exists for effective antiobesity medications, which are largely unaffordable in most countries,” Dr. Levi, from Royal Free Hospital NHS Trust, London, said in a press release.

“We show that these drugs can actually be produced and sold profitably for low prices,” he summarized. “A public health approach that prioritizes improving access to medications should be adopted, instead of allowing companies to maximize profits,” Dr. Levi urged.

Dr. Levi and colleagues studied the oral agents orlistat, naltrexone/bupropion, topiramate/phentermine, and semaglutide, and subcutaneous liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide (all approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat obesity, except for oral semaglutide and subcutaneous tirzepatide, which are not yet approved to treat obesity in the absence of type 2 diabetes).

“Worldwide, more people are dying from diabetes and clinical obesity than HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria combined now,” senior author Andrew Hill, MD, department of pharmacology and therapeutics, University of Liverpool, England, pointed out.

We need to repeat the low-cost success story with obesity drugs

“Millions of lives have been saved by treating infectious diseases at low cost in poor countries,” Dr. Hill continued. “Now we need to repeat this medical success story, with mass treatment of diabetes and clinical obesity at low prices.”

However, in an accompanying editorial, Eric A. Finkelstein, MD, and Junxing Chay, PhD, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, maintain that “It would be great if everyone had affordable access to all medicines that might improve their health. Yet that is simply not possible, nor will it ever be.”

“What is truly needed is a better way to ration the health care dollars currently available in efforts to maximize population health. That is the challenge ahead not just for [antiobesity medications] but for all treatments,” they say.

“Greater use of cost-effectiveness analysis and direct negotiations, while maintaining the patent system, represents an appropriate approach for allocating scarce health care resources in the United States and beyond,” they continue.

Lowest current patented drug prices vs. estimated generic drug prices

New medications for obesity were highly effective in recent clinical trials, but high prices limit the ability of patients to get these medications, Dr. Levi and colleagues write.

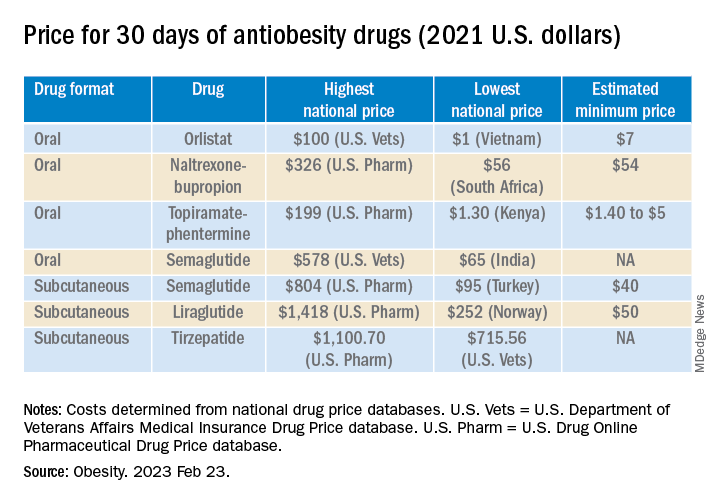

They analyzed prices for obesity drugs in 16 low-, middle-, and high-income countries: Australia, Bangladesh, China, France, Germany, India, Kenya, Morocco, Norway, Peru, Pakistan, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Vietnam.

The researchers assessed the price of a 30-day supply of each of the studied branded drugs based on the lowest available price (in 2021 U.S. dollars) from multiple online national price databases.

Then they calculated the estimated minimum price of a 30-day supply of a potential generic version of these drugs, which included the cost of the active medicinal ingredients, the excipients (nonactive ingredients), the prefilled injectable device plus needles (for subcutaneous drugs), transportation, 10% profit, and 27% tax on profit.

The national prices of the branded medications for obesity were significantly higher than the estimated minimum prices of potential generic drugs (see Table).

The highest national price for a branded oral drug for obesity vs. the estimated minimum price for a potential generic version was $100 vs. $7 for orlistat, $199 vs. $5 for phentermine/topiramate, and $326 vs. $54 for naltrexone/bupropion, for a 30-day supply.

There was an even greater difference between highest national branded drug price vs. estimated minimum generic drug price for the newer subcutaneously injectable drugs for obesity.

For example, the price of a 30-day course of subcutaneous semaglutide ranged from $804 (United States) to $95 (Turkey), while the estimated minimum potential generic drug price was $40 (which is 20 times lower).

The study was funded by grants from the Make Medicines Affordable/International Treatment Preparedness Coalition and from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Coauthor Francois Venter has reported receiving support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, U.S. Agency for International Development, Unitaid, SA Medical Research Council, Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, Gilead, ViiV, Mylan, Merck, Adcock Ingram, Aspen, Abbott, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Virology Education, SA HIV Clinicians Society, and Dira Sengwe. The other authors and Dr. Chay have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Finkelstein has reported receiving support for serving on the WW scientific advisory board and an educational grant unrelated to the present work from Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.