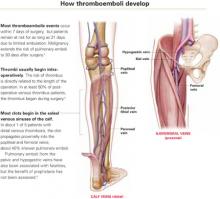

- Prophylaxis must start before surgery for maximal benefit, since at least 50% of postoperative thromboembolic disease begins intraoperatively.

- A consensus conference found that prophylaxis reduced fatal pulmonary emboli by 75% in 7,000 gynecologic surgery patients.

- Low-dose unfractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparin appear similarly effective in reducing thromboembolic disease in perioperative patients, but it is unclear which form has fewer bleeding complications.

The case is strong for routine prophylaxis against venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The primary reasons: efficacy, ease of use, and safety.

This article reviews the evidence on routine prophylaxis, pros and cons of mechanical and drug therapies (including a comparison of 2 heparins), patient risk factors, and cost-effectiveness. A table (page 32) lists patient characteristics for low, moderate, high, and very high levels of risk, with corresponding appropriate preventive measures.

Routine prophylaxis is a wiser strategy than postevent treatment or surveillance because:

- Thromboembolism is a stealthy adversary, particularly pulmonary embolism. Between 10% and 20% of patients with pulmonary emboli die, often within 30 minutes of the sentinel complaint.

- Even when pulmonary embolus is documented during autopsy, as many as 80% of patients have no antecedent clinical evidence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT)—and no chance of life-saving therapy.2

- Surveillance is the least desirable preventive option due to lack of sensitivity of noninvasive tests for thromboembolic disease.

Scope of thromboembolic disease

Thromboembolism is the leading potentially preventable cause of hospital fatality.1

In postoperative gynecologic surgery patients, pulmonary embolism occurs in 0.1% to 5% of cases, depending on risk.2 Venous thrombosis occurs on average in 15% of postoperative gynecologic surgery patients, with a range of 5% to 29%, depending on patient risk factors and the surgical procedures performed.3 Almost 50% of gynecologic patients undergoing surgery for cancer develop a lower-extremity venous thrombosis if left untreated.4

Overall, thromboembolic disease is linked with some 500,000 hospital admissions every year. Pulmonary embolism, the most serious complication, causes 60,000 to 200,000 deaths annually.

High risk of recurrence. Postthrombotic syndrome is characterized by pain, swelling, and leg ulceration. At least 50% of patients successfully treated for proximal venous thrombosis (thigh) and about 33% treated for distal venous thrombosis (calf) develop postthrombotic syndrome.1 The risk for recurrent thrombosis is high.

Risk factors are listed in TABLE 1. The risk of fatal pulmonary embolism is directly related to age; persons over 60 are at greatest risk. When the patient is obese—particularly when she exceeds 120% of ideal body weight—the risk is even greater due to venous stasis.

TABLE 1

Risk factors for thromboembolism

| Age |

| Estrogen use |

| Extended pelvic surgery |

| Hypercoagulable states |

| Immobility |

| Indwelling central venous catheter(s) |

| Lower-extremity paralysis |

| Malignancy |

| Medical illnesses |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Nephrotic syndrome |

| Obesity |

| Pregnancy |

| Prior thromboembolic disease |

| Radiation therapy |

| Trauma |

| Varicose veins |

Common hypercoagulable states

Activated protein C resistance, the most common thrombophilia, occurs in 3% to 7% of Caucasians (TABLE 2).7 It is usually associated with factor V Leiden mutation.

Prothrombin gene mutation G20210A, the next most common thrombophilia, occurs in 2% of Caucasians.7

Antiphospholipid antibody syndromes are acquired thrombophilias that may be associated with arterial and venous thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and complications of pregnancy.8

Hyperhomocystinemia may be congenital or acquired. It is associated with venous thromboembolism and early atherosclerosis with arterial thrombosis.

Thrombosis is more likely with multiple predisposing factors. Most patients with one of the thrombophilia syndromes do not have sentinel thrombotic events unless they are further challenged by environmental risks such as oral contraceptives (OCs), pregnancy, prolonged immobilization, or surgery.9

Risk is markedly enhanced if multiple predisposing factors are present. For example, when factor V Leiden mutation and hyperhomocystinemia coexist, the risk for thrombosis increases 10 to 20 times over that of patients with neither abnormality.10 This combined risk far exceeds the sum of risks for each abnormality alone.

TABLE 2

Common hypercoagulable conditions

| Factor V Leiden mutation |

| Prothrombin gene mutation G20210A |

| Antiphospholipid antibody |

| Lupus anticoagulant |

| Anticardiolipin |

| Protein C deficiency |

| Protein S deficiency |

| Antithrombin III deficiency (Heparin cofactor II) |

| Plasminogen deficiency |

| Hyperhomocystinemia |

| Myeloproliferative disorders |

| Polycythemia |

| Primary thrombocytosis |

When to test for thrombophilias

Although women with thrombophilias are at high risk for thromboembolic disease, it is unclear whether identifying the thrombophilia is more beneficial than universal prophylaxis. If a patient has a personal or family history of thromboembolic disease—especially a patient with Caucasian ancestry—testing is probably warranted. While documentation of the thrombophilia may not help with perioperative management, it may be useful for long-term care.

Testing for factor V Leiden mutation is recommended due to its prevalence. If the results are negative in a patient at risk, test for prothrombin gene mutation G20210A, as well as deficiencies in the naturally occurring inhibitors protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III.

Assess antiphospholipid antibodies in women who have experienced recurrent fetal loss or early pregnancy-induced hypertension.