Clinical Review

Endometriosis: Expert answers to 7 crucial questions on diagnosis

The notorious delay in diagnosis associated with this condition stems in part from its ability to mimic other diseases. The expert answers...

Jessica C. Francis, MD, and Jennifer E. Dietrich, MD, MSc

Dr. Francis is Assistant Professor and Associate Director, Residency Program, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Dr. Dietrich is Chief, Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and Division and Fellowship Director, Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, and Associate Professor, Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Developed in partnership with the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology (NASPAG).

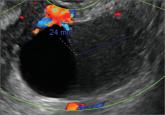

An abdominal ultrasound reveals a normal appendix, and pelvic ultrasonography reveals that the right ovary is enlarged (volume = 25 mL). The left ovary shows no obvious mass and a volume of 8 mL.

She is taken to the operating room, where you perform diagnostic laparoscopy.

Diagnosis: Adnexal torsion (FIGURE 1).

Treatment: Surgical detorsion with or without cystectomy.

Ultrasonography certainly can be useful in determining the size of an adnexal mass. An adnexal volume of less than 20 mL is strong evidence against adnexal torsion in an adolescent. This information, in addition to the remainder of the clinical picture, can be used to determine if surgery is immediately necessary or can be delayed.3

Several studies have attempted to draw a link between size of an ovarian mass and risk of malignancy. Unfortunately, such attempts have been unsuccessful, especially for large and small masses.4 In addition, many studies have explored the use of Doppler technology to confirm a diagnosis of torsion found on sonography. Studies have shown, however, that diminished or absent Doppler flow is not a reliable finding and that ovarian blood flow can be preserved in cases of surgically confirmed adnexal torsion.5

Torsion ultimately is a clinical diagnosis, and medical history and physical examination are critical in the decision-making process. The decision to go to the operating room for further evaluation never should be made based on ultrasound findings alone, as not all ovarian torsions result in a mass greater than 20 mL.

Clinical pearl. In the setting of a known adnexal cyst, it is important to impress upon patients and their parents the warning signs of torsion and the need to proceed directly to the emergency center if acute pelvic pain occurs.

Historically, adnexal torsion is correlated with oophorectomy, but recent studies indicate that ovarian function can be preserved in the majority of cases with detorsion and cystectomy alone.6,7 In cases in which no cyst is present, detorsion is therapeutic.

In addition, studies have shown that the appearance of the ovary is not indicative of damage to the ovary. Regardless of “necrotic” appearance, the adnexa should be preserved.8,9 Ovarian function after detorsion also has been assessed in a case series that showed normal follicular development on ultrasonography in more than 90% of patients after detorsion. In this group, 6 of 102 patients with torsion eventually underwent in vitro fertilization and, in all 6 patients, oocytes retrieved from the ischemic ovary were fertilized.10

Case 3: 15-year-old girl with nontender, palpable abdominal mass

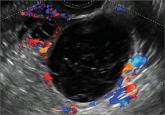

A 15-year-old adolescent comes to your office for a well woman exam and to establish gynecologic care. Abdominal examination reveals a mass below the umbilicus that is nontender to palpation. The remainder of the examination is normal, and the patient is sent for ultrasonography. Results reveal a complex-appearing mass in the left ovary that measures 8 cm x 7 cm x 8 cm. The report states that the mass shows areas of fat and calcifications. There are no other abnormalities noted in the abdomen or pelvis.

Diagnosis: Dermoid cyst.

Treatment: Surgical intervention versus expectant management.

Germ cell ovarian tumors are a diverse category of tumors that include both benign and malignant disease. The ovarian teratoma (“dermoid”) is the most common and perhaps best-known example of a benign ovarian germ cell tumor (FIGURE 2). While the incidence in the general population is unknown, dermoids account for approximately 65% of adnexal masses in pediatric patients presenting for treatment.11 Most of the time, patients with ovarian dermoids will be asymptomatic; however, pain is the most common presenting symptom.

The spectrum of sonographic features includes:

The notation of internal vascularity is concerning for malignancy.12

Fortunately, malignant ovarian germ cell tumors are much less common than benign lesions. Of these, the most common pediatric ovarian germ cell tumor is dysgerminoma (FIGURE 3).13

Clinical pearl. A unique consideration in patients with dysgerminoma or choriocarcinoma is the possible diagnosis of XY gonadal dysgenesis, or Swyer syndrome.14,15 This may be seen in young girls with female external genitalia and primary amenorrhea. Depending on the level of concern, obtaining a karyotype also may be beneficial.13

The notorious delay in diagnosis associated with this condition stems in part from its ability to mimic other diseases. The expert answers...

In this commentary, Dr. Javier F. Magrina describes screening techniques that differentiate benign from malignant adnexal masses, and discusses...

Whether you scan the patient yourself or refer her to an ultrasonography lab, you need to be able to identify both physiologic and pathologic...

A 25-year-old patient presents with pelvic pain and dyspareunia. A 19-year-old patient with a history of ovarian cystectomy for dermoid cyst...

Myriad sonographic features characterize cystic adnexal pathology. Here, three cases of benign, resolving cysts, including when to follow-up.