About 10% of all reproductive-aged women and 35% to 50% of women with pelvic pain and infertility are affected by endometriosis.1,2 The disease typically involves the reproductive tract organs, anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and uterosacral ligaments. However, disease outside of the reproductive tract occurs frequently and has been found on all organs except the spleen.3

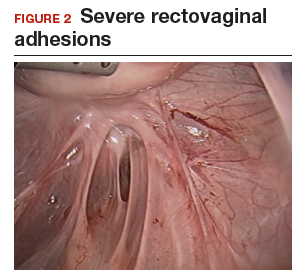

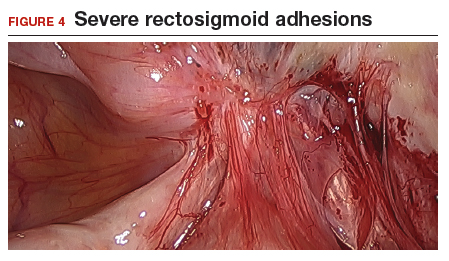

The bowel is the most common site for extragenital endometriosis, affected in an estimated 3.8% to 37% of patients with known endometriosis.4-7 Implants may be superficial, involving the bowel serosa and subserosa (FIGURE 1), or they can manifest as deeply infiltrating lesions involving the muscularis and mucosa (FIGURE 2). The rectosigmoid colon is the most common location for bowel endometriosis, followed by the rectum, ileum, appendix, and cecum4,8 (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5). Case reports also have described endometrial implants on the stomach and transverse colon.9 Although isolated bowel involvement has been recognized, most patients with bowel endometriosis have concurrent disease elsewhere.2,4

Historically, segmental resection was performed regardless of the anatomical location of the lesion.10 Even today, many surgeons continue to routinely perform segmental bowel resection as a first-line surgical approach.11 Unnecessary segmental resection, however, places patients at risk for short- and long-term postoperative morbidity, including the possibility of permanent ostomy. Modern surgical techniques, such as shaving excision and disc resection, have been performed to successfully treat bowel endometriosis with excellent long-term outcomes and fewer complications when compared with traditional segmental resection.2,12-16

In this article, we focus on the clinical indications and surgical techniques for video-laparoscopic management, but first we describe the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of bowel endometriosis.

Pathophysiology of bowel endometriosis

The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains unknown, as no single mechanism explains all clinical cases of the disease. The most popular proposed theory describes retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes.17 Once inside the peritoneal cavity, endometrial cells attach to and invade healthy peritoneum, establishing a blood supply necessary for growth and survival.

In the case of bowel endometriosis, deposition of effluxed endometrial cells may lead to an inflammatory response that increases the risk of adhesion formation, leading to potential cul-de-sac obliteration. Lesions may originate as Allen-Masters peritoneal defects, developing into deeply infiltrative rectovaginal septum lesions. The anatomical shelter theory contributes to lesions within the pelvis, with the rectosigmoid colon blocking the cephalad flow of effluxed menstrual blood from the pelvis, thus leading to a preponderance of lesions in the pelvis and along the rectosigmoid colon.2

Continue to: Clinical presentation and diagnosis...