- Resection of an endometrioma in severe disease, using a “stripping” technique

- Ovarian cystectomy

- Resection of endometriosis from the left ligament

- Resection of endometriosis on the bladder

These videos were provided by Anthony Luciano, MD.

Endometriosis affects 7% to 10% of women in the United States, mostly during reproductive years.1 The estimated annual cost for managing the approximately 10 million affected women? More than $17 billion.2 The added cost of this chronic disease, with recurrences of pain and infertility, comes in the form of serious life disruption, emotional suffering, marital and social dysfunction, and diminished productivity.

Although the prevalence of endometriosis is highest during the third and fourth decades of life, the disease is also common in adolescent girls. Indeed, 45% of adolescents who have chronic pelvic pain are found to have endometriosis; if their pain does not respond to an oral contraceptive (OC) or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, 70% are subsequently found at laparoscopy to have endometriosis.3

What is it?

Endometriosis is the presence of functional endometrial tissue outside the uterus, such as eutopic endometrium. The disease responds to effects of cyclic ovarian hormones, proliferating and bleeding with each menstrual cycle, which often leads to diffuse inflammation, adhesions, and growth of endometriotic nodules or cysts (FIGURE 1).

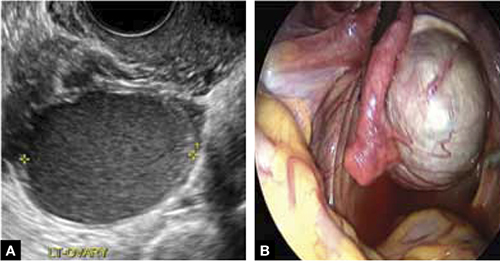

FIGURE 1 Drainage will not suffice

Surgical management of ovarian endometriomas must go beyond simple drainage, which has little therapeutic value because symptoms recur and endometriomas re-form quickly after simple drainage in almost all patients.Symptoms tend to reflect affected organs:

- Because the pelvic organs are most often involved, the classic symptom triad of the disease comprises dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.

- Urinary urgency, dysuria, dyschezia, and tenesmus are frequent complaints when the bladder or rectosigmoid is involved.

- When distant organs are affected, such as the upper abdomen, diaphragm, lungs, and bowel, the patient may complain of respiratory symptoms, hemoptysis, pneumothorax, shoulder pain, upper abdominal pain, and episodic gastrointestinal dysfunction.

The hallmark of endometriosis is catamenial symptoms, which are usually cyclic and most severe around the time of menses. Clinical signs include palpable tender nodules and fibrosis on the anterior and posterior cul de sac, fixed retroverted or anteverted uterus, and adnexal cystic masses.

Because none of these symptoms or signs is specific for endometriosis, diagnosis relies on laparoscopy, which allows the surgeon to:

- visualize it in its various appearances and locations (FIGURE 2)

- confirm the diagnosis histologically with directed excisional biopsy

- treat it surgically with either excision or ablation.

In this article, we describe various surgical techniques for the management of endometriosis. Beyond resection or ablation of lesions, however, your care should also be directed to postoperative measures to prevent its recurrence and to avoid repeated surgical interventions—which, regrettably, are much too common in women who are afflicted by this enigmatic disease.

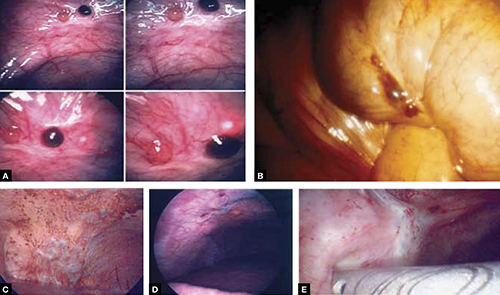

FIGURE 2 Endometriosis: A disease of varying appearance

Lesions of endometriosis can be pink, dark, clear, or white on the pelvic sidewall (A), bowel (B), and diaphragm (C); under the rib cage (D); and on the ureter (E) (left ureter shown here).

CASE Severe disease in a young woman

S. D. is a 22-year-old unmarried nulligravida who came to the emergency service complaining of acute onset of severe low abdominal pain, which developed while she was running. She was afebrile and in obvious distress, with diffuse lower abdominal tenderness and guarding, especially on the left side.

Ultrasonography revealed a 7-cm adnexal cystic mass suggestive of endometrioma (FIGURE 3).

Two years before this episode, S. D. underwent laparoscopic resection of a 5-cm endometrioma on the right ovary. Subsequently, she was treated with a cyclic OC, which she discontinued after 1 year because she was not sexually active.

The family history is positive for endometriosis in her mother, who had undergone multiple laparoscopic investigations and, eventually, total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at 40 years of age.

S. D. was treated on the emergency service with analgesics and referred to you for surgical management.

S. D. has severe disease that requires aggressive surgical resection and a lifelong management plan. That plan includes liberal use of medical therapy to prevent recurrence of symptoms and avoid repeated surgical procedures—including the total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy that her mother underwent.

What is the best immediate treatment plan? Should you:

- drain the cyst?

- drain it and coagulate or ablate its wall?

- resect the wall of the cyst?

- perform salpingo-oophorectomy?

You also ask yourself: What is the risk of recurrence of endometrioma and its symptoms after each of those treatments? And how can I reduce those risks?