Histologic analyses of resected endometrioma cyst walls have reported follicle-containing ovarian tissue attached to the stripped cyst wall in 54% of cases.11,12 That observation explains why, and how, ovarian reserve can be compromised after resection of endometrioma.

Further risk: Ovarian failure

In rare cases, excision of endometriomas results in complete ovarian failure, described by Busacca and colleagues, who reported three cases of ovarian failure (2.4%) after resection of bilateral endometriomas in 126 patients.13 They attributed ovarian failure to excessive cauterization that compromised vascularization, as well as to excessive removal of ovarian tissue.

It is important, therefore, to strip the thinnest layer of the cyst capsule and to reduce the amount of electrocoagulation of ovarian stroma as much as possible to safeguard functional ovarian tissue.

CASE continued

S. D. was scheduled for laparoscopy to remove the endometrioma and other concurrent pelvic and peritoneal pathology, such as endometriosis and pelvic adhesions. You also scheduled her for hysteroscopy to evaluate the endometrial cavity for potential pathology, such as endometrial polyps and uterine septum, which appear to be more common in women who have endometriosis.

Nawroth and co-workers14 found a much higher incidence of endometriosis in patients who had a septate uterus. Metalliotakis and co-workers15 found congenital uterine malformations to be more common in patients who had endometriosis, compared with controls; uterine septum was, by far, the most common anomaly.

CASE continued

Hysteroscopy revealed a small and broad septum, which was resected sharply with hysteroscopic scissors (FIGURE 4). Laparoscopy revealed a 7-cm endometrioma on the left ovary, with adhesions to the posterior broad ligament and pelvic sidewall. S. D. also had deep implants of endometriosis on the left pelvic sidewall, the posterior cul de sac, the right pelvic sidewall, and the right ovary, which was cohesively adherent to the ovarian fossa.

As you expected, S. D. has stage-IV disease, according to the revised American Fertility Society Classification.

Following adhesiolysis, the endometrioma was resected (see VIDEO 1). Because of the large ovarian defect, the edges of the ovary were approximated with imbricating running 3-0 Vicryl suture. Deep endometriosis was also resected. Superficial endometriosis was peeled off or coagulated using bipolar forceps.

Note: Alternatively, and with comparable results, resection may be performed with a laser or other energy source. We prefer resection, rather than ablation, of deep endometriosis, but no data exists to support one technique over the other.

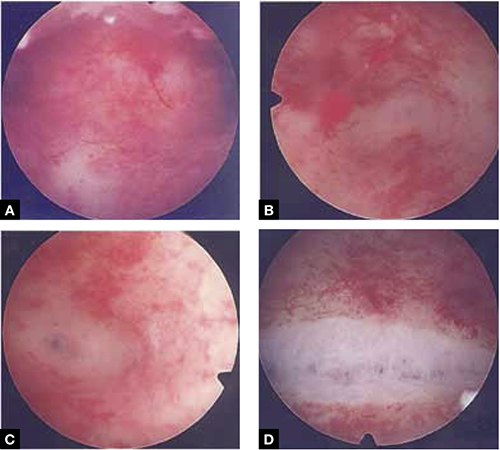

FIGURE 4 Septate uterus with deep cornua

Through the hysteroscope, a shallow septum is visible at the fundus of the uterus, dividing the upper endometrial cavity into two chambers (A), with deep cornua on the left (B) and right (C). Normal fundal anatomy is restored by septolysis along the avascular plane (D).

Technique: How we resect endometrioma

In removing endometrioma (see VIDEO 2), it is important to grasp the thinnest part of the cyst wall and progressively strip it, to avoid removing excess ovarian tissue and to reduce the risk of compromising ovarian reserve.

After draining the endometrioma of its chocolate-colored fluid, we irrigate and drain the cyst several times with warm lactated Ringers’ solution to promote separation of the cyst wall from underlying stroma and better identify the dissection plane. The cyst wall is inspected by introducing the laparoscope into the cyst to examine its surface, which is often laden with implants of deep and superficial endometriosis.

If we cannot easily identify the plane of dissection along the edges, we may evert the cyst and make an incision at its base to create a wedge between the wall of the cyst and underlying stroma. The edge of the incised wall is then grasped and retracted to create a space between the wall and the underlying stroma, from which it is progressively stripped from the ovary.

Traction and counter-traction are the hallmarks of dissection here; sometimes, we use laparoscopic scissors to sharply resect the ovarian stromal attachments that adhere cohesively to the cyst wall. This technique is continued until the entire cyst wall is removed. When follicle-containing ovarian tissue remains attached to the cyst wall, we introduce the closed tips of the Dolphin forceps between the cyst wall and adjacent follicle-containing stroma, spread the tips apart, and recover the true plane of dissection between the thin wall of the cyst and stroma.

After the wall of the cyst is removed, the ovarian crater invariably bleeds because blood vessels supplying the wall have been separated and opened. Utilizing warm lactated Ringers’ solution, we copiously irrigate the bleeding ovarian stroma to identify each bleeding vessel and, by placing the tips of the micro-bipolar forceps on either side of the bleeder, individually coagulate each vessel, thus inflicting minimal thermal damage to the surrounding stroma.