T2 images. By contrast to the T1-weighted sequence, the T2-weighted sequences emphasize fluid signal; structures such as the ventricles, which contain CSF, therefore will be bright (hyper-intense). Pathology that produces edema or fluid, such as edema surrounding demyelinating lesions or infections, also will show bright hyper-intense signal. In T2-weighted images of the brain, white matter shows lower signal intensity than the cortex because of the relatively lower water content in white matter tracts and myelin sheaths.

Fluid attenuation inversion recovery. FLAIR images are generated so that the baseline bright T2 signal seen in normal structures, such as the CSF, containing ventricles is cancelled out, or attenuated. In effect, this subtraction of typical background hyper-intense fluid signal leaves only abnormal T2 bright hyper-intense signal, such as vasogenic edema surrounding tumors, cytotoxic edema within an infarction, or extra-axial fluid collections such as a subarachnoid or subdural hemorrhage.

Diffusion-weighted imaging. DWI utilizes the random motion (ie, diffusion) of water molecules to generate contrast. In this regard, the diffusion of any molecule is influenced by its interaction with other molecules (eg, white-matter fibers and membranes, and macromolecules). Diffusion patterns therefore reflect details about tissue boundaries; as such, DWI is sensitive to a number of neurologic processes, such as ischemia, demyelinating disease, and some tumors, which restrict the free motion of water. DWI detects this so-called restricted diffusion and displays an area of bright signal.

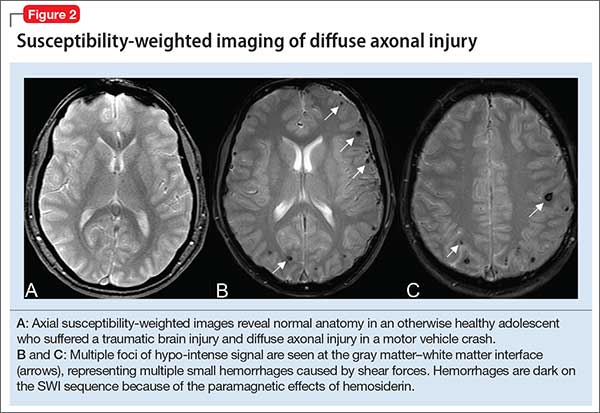

Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI). In the pediatric population, SWI (Figure 2) utilizes a long-echo, 3-dimensional, velocity-compensated gradient recalled echo for image acquisition2 and, ultimately, leverages susceptibility differences across tissues by employing the phase image to identify these differences. SWI, which uses both magnitude and phase images and is remarkably sensitive to venous blood (and blood products), iron, and calcifications, therefore might be of increasing utility in pediatric patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Figure 2B). As such, SWI has become a critical component of many pediatric MRI studies.3

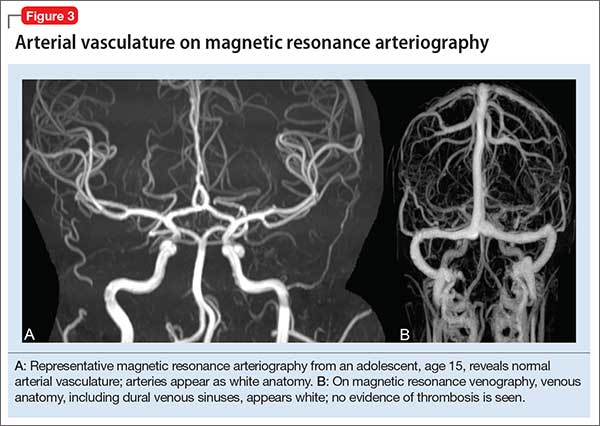

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) (Figure 3A) is helpful for assessing intracranial arteries and may be employed in the evaluation of:

- vessel pathology and injury underlying stroke, such as vessel occlusion or injury

- patterns of vessel involvement suggestive of vasculitis

- developmental or acquired structural vascular abnormalities, such as aneurysm or vascular malformations

- determination of tumor blood supply.

MRA can be performed without or with contrast, although MRA with contrast might provide a higher quality study and therefore be of greater utility. Of note: The spatial resolution of MRA is not as good as CT angiography; abnormalities, such as a small aneurysm, might not be apparent.

Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) (Figure 3B) is most commonly performed when the possibility of thrombosis of the dural venous sinuses is being considered; it also is employed to evaluate vascular malformations, tumor drainage patterns, and other pathologic states. As with MRA, MRV can be performed without or with contrast, although post-contrast MRV is generally of higher quality and might be preferred when assessing for sinus thrombosis.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) resides at the border between research and clinical practice. In children and adolescents, MRS provides data on neuronal and axonal viability as well as energetics and cell membranes.4 Pediatric neurologists often use MRS to evaluate for congenital neurometabolic disease; this modality also can help distinguish between an active intracranial tumor from an abscess or gliosis.5

Neuroimaging in pediatric neuropsychiatric conditions: Evidence, guidance

Delirium (altered mental status). The acute neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by impaired attention and sensorium might have a broad underlying etiology, but it is always associated with alteration of CNS neurophysiology. Children with neurostructural abnormalities might have increased vulnerability to CNS insult and therefore be at increased risk of delirium.6 Additionally, delirium can present subtly in children, with the precise signs dependent on the individual patient’s developmental stage.

Neuroimaging may be helpful when an infectious, inflammatory, toxic, or a metabolic basis for delirium is suspected, or when a patient has new focal neurologic findings. In this regard, focal neurologic findings suggest an underlying localizable lesion and warrant dedicated neuroimaging to localize the lesion.

In general, the differential diagnosis should guide consideration of neuroimaging. When considering the possibility of an unwitnessed seizure in a child who presents with altered mental status, neuroimaging certainly is an important component of the workup.

As another example, when underlying trauma, intracranial hemorrhage, or mass is a possibility in acute delirium, urgent head CT is appropriate. In non-emergent cases, MRI is the modality of choice. In immunocompromised patients presenting with delirium, maintain a low threshold for neuroimaging with contrast to rule out opportunistic intracranial infection.

Last, in children who have hydrocephalus with a shunt, delirium could be a harbinger of underlying shunt malfunction, warranting a “shunt series.”