Traumatic brain injury. Prompt evaluation and intervention for TBI can significantly affect overall outcome. Moreover, there has been increased enthusiasm around the pre-hospital assessment of TBI severity using (1) any of several proprietary testing systems (eg, Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing [ImPACT]) plus (2) standard clinical staging, which is based on duration of loss of consciousness, persistence of memory loss, and the Glasgow Coma Scale score.

The goal for any TBI patient during the acute post-injury phase is to minimize continued neuronal injury from secondary effects of TBI, such as cerebral edema and herniation, and to optimize protection of surviving brain tissue; neuroimaging is a critical component of assessment during both acute and chronic recovery periods of TBI.21

The optimal imaging modality varies with the amount of time that has passed since initial injury.22 Urgent neuroimaging (the first 24 hours after brain injury) is typically obtained using head CT to assist decision-making in acute neurosurgical management. In this setting, head CT is fast and efficient; minimizes the amount of time that the patient is in the scanner; and provides valuable information on the acuity and extent of injury, degree of cerebral edema, and evidence or risk of pending herniation.

On the other hand, MRI is superior to CT during 48 to 72 hours after injury, given its higher resolution; superior imaging of the brainstem and deep gray nuclei; and ability to detect axonal injury, small contusions, and subtle neuronal damage. Specifically, SWI sequences can be particularly helpful in TBI for detecting diffuse axonal injury and micro-hemorrhages; several recent studies also suggest that SWI may be of particular value in pediatric patients with TBI.23

Additionally, given the increased sensitivity of MRI to detect subtle injuries, this modality can assist in identifying chronic sequelae of brain injury—thus contributing to determining of chronic therapy options and assisting with long-term prognosis. Gross structural changes resulting from TBI often are evident even in the acute post-injury phase; synaptic remodeling continues, however, for an indefinite period after injury, and this remodeling capacity is even more pronounced in the highly plastic brain of a young child.

Microstructural changes might not be detectable using traditional, readily available imaging sequences (CT, MRI). When those traditional modalities are used in concert with functional imaging techniques (eg, PET to evaluate cerebral metabolism and SPECT imaging which can detect abnormalities in cerebral blood flow), the combination of older and newer might provide a more complete picture of recovery after TBI.24

The important role of neuroimaging in severe TBI is intuitive. However, it is important to consider the role of neuroimaging in mild TBI in children, especially in the setting of repetitive mild injury.25 A growing body of evidence supports close, serial monitoring of children after even mild closed head injury for neurologic and psychiatric sequelae. Although it is rare that a child who is awake, interactive, and lacking focal neurologic deficits would need emergent (ie, CT) imaging after mild closed head injury, there might be a role for MRI later in the course of that child’s recovery—especially if recovery is complicated by clinical sequelae of mild TBI, such as cognitive impairment, headaches, or altered behavior.

When is additional neuroimaging needed?

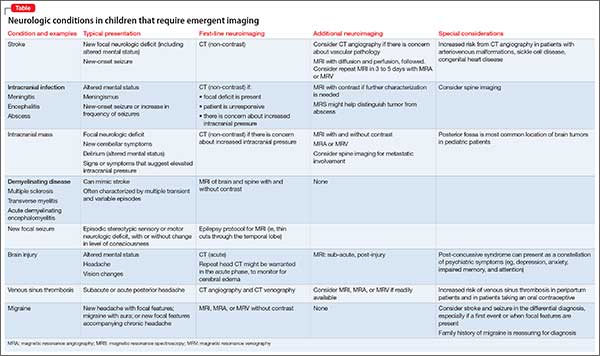

It’s worthwhile briefly reviewing 4 scenarios that you might encounter, when you work with children and adolescents, in which urgent or emergent neuroimaging (often with consultation) should be obtained. The Table describes these situations and appropriate first- and second-line interventions.

1. When the presentation of your patient is consistent with an acute neurologic deficit, acute TBI, progressive neuropsychiatric decline, CNS infection, mass, demyelinating process, or toxic exposure, neuroimaging is likely critical.

2. In patients with progressive neurologic decline, including loss of developmental milestones, MRI, MRS, and referral to neurology should be part of the comprehensive evaluation.

3. In young children who exhibit a decrease in head circumference on growth curves, MRI is important to evaluate for underlying structural causes.

4. Pediatric patients with symptoms consistent with either stroke (ie, a new, persistent neurologic deficit) or a demyelinating process (eg, multiple episodes of variable transient focal neurologic symptoms), MRI should be obtained without compunction.

Consultation with pediatric neuroradiology

In deciding whether to obtain neuroimaging for a particular case, you should discuss your concerns with the pediatric radiologist or pediatric neuroradiologist, who will likely provide important guidance on key aspects of the study (eg, modifying slice thickness in a particular scan; recommending the use of contrast; including MRS in the order for imaging; performing appropriate vessel imaging). Consider asking 1 or more important questions when you discuss a patient’s presentation with the pediatric radiologist or pediatric neuroradiologist: