ADHD. The diagnosis of ADHD remains a clinical one; for the typical pediatric patient with ADHD but who does not have focal neurologic deficits, neuroimaging is unnecessary. Some structural MRI studies of youth with ADHD suggest diminished volume of the globus pallidus, putamen, and caudate7; other studies reveal changes in gyrification and cortical thickness8 in regions subserving attentional processes. However, intra-individual and developmental-related variability preclude routine use of neuroimaging in the standard diagnostic work-up of ADHD.

Nevertheless, neuroimaging should be strongly considered in a child with progressive worsening of inattention, especially if combined with other psychiatric or neurologic findings. In such a case, MRI should be obtained to evaluate for a progressive neurodegenerative leukoencephalopathy (eg, adrenoleukodystrophy).9

Depressive and anxiety disorders. In pediatric patients who exhibit depressive or anxiety symptoms, abnormalities have been observed in cortical thickness10 and gray matter volume,11,12 and functional signatures13 have been identified in the circuitry of the prefrontal amygdala. No data suggest that, in an individual patient, neuroimaging can be of diagnostic utility—particularly in the absence of focal neurologic findings.

That being said, headache and other somatic symptoms are common in pediatric patients with a mood or anxiety disorder. Evidence for neuroimaging in the context of pediatric headache suggests that MRI should be considered when headache is associated with neurologic signs or symptoms, such as aura, or accompanied by focal neurologic deficit.14

Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) and pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS). Neuroimaging studies of patients with confirmed PANDAS or PANS are rare, but group analyses suggest a decreased average volume of the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus in patients with PANDAS compared with healthy comparison subjects, although total cerebral volume does not appear to differ.15 Moreover, thalamic findings in patients with PANDAS have been noted to be similar to what is seen in patients with Sydenham’s chorea.

The most recent consensus statement regarding the treatment and assessment of PANDAS and PANS recommends ordering brain MRI when other conditions are suspected (eg, CNS, small vessel vasculitis, limbic encephalitis) or when the patient has severe headache, gait disturbance, cognitive deterioration, or psychosis.16 Furthermore, the consensus statement notes the potential utility of T2-weighted imaging with contrast to evaluate inflammatory changes in the basal ganglia.16

Autism spectrum disorder. Significant progress has been made during the past decade on the neuroanatomic characterization of ASD. Accumulating data indicate that, in pediatric patients with ASD, (1) development of white matter and gray matter is disrupted early in the course of the disorder and (2) cortical thickness is increased in regions subserving social cognition.17,18

Several studies have examined the presence of patient-level findings in samples of pediatric patients with ASD. Approximately 8% of pediatric patients with ASD were found to have some abnormality on routine brain MRI, the most common being white-matter signal abnormalities, dilated Virchow-Robin space, and temporal lobe abnormalities.19

Although abnormalities might be present in a large percentage of individual scans, routine screening MRI is unlikely to be of clinical utility in youth with ASD. In fact, no recommendation for routine MRI screening in patients with ASD has been made by the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, the Child Neurology Society of the American Academy of Neurology, or the American Academy of Pediatrics.

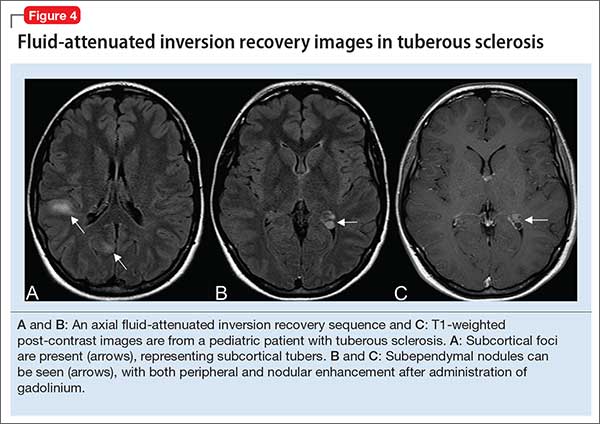

However, in patients with an underlying neurostructural disease that is phenotypically associated with ASD-like symptoms, imaging might be of use. In tuberous sclerosis, for example, MRI is especially important to classify intracranial lesions; determine burden and location; or identify treatment options (Figure 4). For patients with tuberous sclerosis—of whom more than one-third meet diagnostic criteria for ASD20—MRI study should include FLAIR, spin-echo, and gradient-echo sequences.

Movement disorders. Hyperkinetic movement disorders, including tic disorders and drug-induced movement disorders (eg, tremor) are common in pediatric patients. In pediatric patients with a tic disorder or Tourette’s disorder (TD), neuroimaging typically is unnecessary, despite the suggestion that the caudate nucleus volume is reduced in groups of patients with TD.

Many CNS-acting medications can exacerbate physiologic tremor; in pediatric patients with symptoms of a movement disorder, home medications should be carefully reviewed for potentially offending agents. When the patient is clinically and biochemically euthyroid and medication-induced movement disorder has been ruled out, or when the patient meets clinical diagnostic criteria for TD or a tic disorder, routine neuroimaging generally is unnecessary.

When tremor accompanies other cerebellar signs, such as ataxia or dysmetria, strongly consider MRI of the brain to evaluate pathology in the posterior fossa. In addition, neuroimaging should be considered for children with a new-onset abnormality on neurologic exam, including rapid onset of abnormal movements (other than common tics), continuous progressive worsening of symptoms, or any loss of developmental milestones.

Last, although tics and stereotypies often are transient and wane with age, other abnormal movements, such as dystonia, chorea, and parkinsonism (aside from those potentially associated with antipsychotic use), are never expected during typical development and warrant MRI.