Although the peak age of onset of bipolar disorder (BD) is between 20 and 40 years,1 some patients develop BD later in life. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force has classified the illness into 3 categories:

- early-onset bipolar disorder (EOBD), in which the first manic episode occurs before age 40

- late-onset bipolar disorder (LOBD), in which the initial manic/hypomanic episode occurs after age 50

- older-age bipolar disorder (OABD), in which the first manic/hypomanic episode occurs after age 60.2

OABD represents 25% of the population with BD.3 OABD differs from EOBD in its clinical presentation, biological factors, and psychiatric and somatic comorbidities.4 Studies suggest OABD warrants a more extensive workup to rule out organic causes because symptoms are often attributable to a variety of organic etiologies.

This article describes 3 cases of OABD, including treatments and outcomes. We discuss general treatment recommendations for patients with OABD as cited in the literature. Further research is needed to expand our ability to better care for this unique population.

CASE 1

Mr. D was a 66-year-old African American male with no psychiatric history. His medical history was significant for hypertension, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. One year ago, he was diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma, and underwent uncomplicated right trisegmentectomy, resection of extrahepatic biliary tree, and complete portal lymphadenectomy, with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy to 2 intrahepatic ducts. He presented to the emergency department (ED) with disorganized behavior for 3 weeks. During that time, Mr. D reported increased distractibility, irritability, hyper-religiosity, racing thoughts, decreased appetite, and decreased need for sleep. There was no pertinent family history.

On mental status examination, Mr. D was agitated, noncooperative, and guarded. His speech was loud and pressured. Mr. D was distractible, tangential, and goal-directed. His Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was 31, which is highly indicative of mania.5 Computed tomography (CT) scan of the head (Figure 1) showed age-related changes but no acute findings. Mr. D was diagnosed with unspecified bipolar disorder and admitted. He was started on divalproex sodium extended release, which was titrated to 1,500 mg/d, and olanzapine, 15 mg nightly, with subsequent improvement. At discharge, his YMRS score was 9.

CASE 2

Mr. M was a 63-year-old African American male with no psychiatric history and a medical history significant for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. He presented to the ED with behavioral changes for 2 weeks. During this time, he experienced decreased need for sleep, agitation, excessive spending, self-conversing, hypersexuality, and paranoia. His family history was significant for schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type.

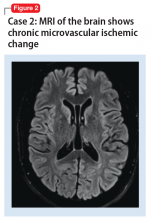

A mental status examination revealed pressured speech, grandiose delusions, hyper-religiosity, flight of ideas, looseness of association, auditory hallucinations, and tangential thought processes. Mr. M’s initial YMRS score was 56. A CT scan of the head revealed no acute abnormality, but MRI of the brain (Figure 2) showed chronic microvascular ischemic change. Mr. M was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and admitted. He was started on quetiapine extended release, which was titrated to 600 mg nightly. Divalproex sodium extended release was titrated to 1,500 mg nightly, with subsequent improvement. At discharge, his YMRS score was 15.

Continue to: CASE 3