CASE 3

Ms. F was a 69-year-old White female with no psychiatric history. Her medical history was significant for hypertension, osteoarthritis, and stage III-C ovarian adenocarcinoma with a debulking surgical procedure 5 years earlier. After that, she received adjuvant therapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin, which resulted in a 10-month disease-free interval. Subsequent progression led to cycles of doxorubicin liposomal and gemcitabine. She was in remission until 1 week earlier, when a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis showed recurrence. She presented to the hospital after disrobing in the street due to hyper-religiosity and divine instruction. She endorsed elevated mood and increased energy despite sleeping only 2 hours daily. Her family psychiatric history was significant for her daughter’s suicide attempt.

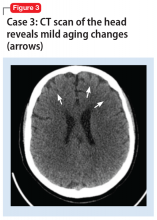

A mental status examination revealed disorganized behavior and agitation. Her speech was loud and pressured. She described a “great” mood with congruent affect. Her thought process was circumstantial and illogical. She displayed flight of ideas, grandiose delusions, and paranoia. Ms. F’s initial YMRS score was 38. Vital signs were significant for an elevated blood pressure of 153/113 mm Hg. A CT scan of the head (Figure 3) showed age-related change with no acute findings. Ms. F was admitted with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder and prescribed olanzapine, 2.5 mg nightly. Due to continued manic symptoms, olanzapine was discontinued, and Ms. F was started on quetiapine, 300 mg nightly, with subsequent improvement. At discharge, her YMRS score was 10.

Differences between EOBD and OABD

BD has always been considered a multi-system illness; however, comorbidity is much more common in OABD than in EOBD. Comorbid conditions are 3 to 4 times more common in patients with OABD.2 Common comorbidities include metabolic syndrome, allergic rhinitis, arthritis, asthma, and cardiovascular disease.

Compared with younger individuals, older patients with BD score lower on the YMRS in the areas of increased activity-energy, language-thought disorder, and sexual interest.6 Psychotic symptoms are less common or less severe in OABD. Although symptom severity is lower, the prevalence of rapid cycling illness is 20% higher in patients with OABD.6 OABD is less commonly associated with a family history.7 This may suggest a difference from the popular genetic component typically found in patients with EOBD.

Cognitive impairment is more commonly found in OABD. Patients with OABD suffer from neuropsychological deficits even during euthymic phases.8 While these deficits may also be found in patients with EOBD, compared with younger patients, older adults are more susceptible to accelerated decline in cognition. OABD can first present within the context of cardiovascular or neuropsychological impairment. It has also been linked to a greater prevalence of white matter hyperintensities compared with EOBD.9,10

Continue to: Treatment is not specific to OABD