The term evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been derided by some as “cookbook medicine.” To others, EBM conjures up the efforts of describing interventions in terms of comparative effectiveness, drowning us in a deluge of “evidence-based” publications. The moniker has also been hijacked by companies to name their Health Economics and Outcomes research divisions. The spirit behind EBM is getting lost. EBM is not just about the evidence; it is about how we use it.1

In this commentary, we describe the concept of EBM and discuss teaching EBM to medical students and residents, its role in continuing medical education, and how it may be applied to practice, using a case scenario as a guide.

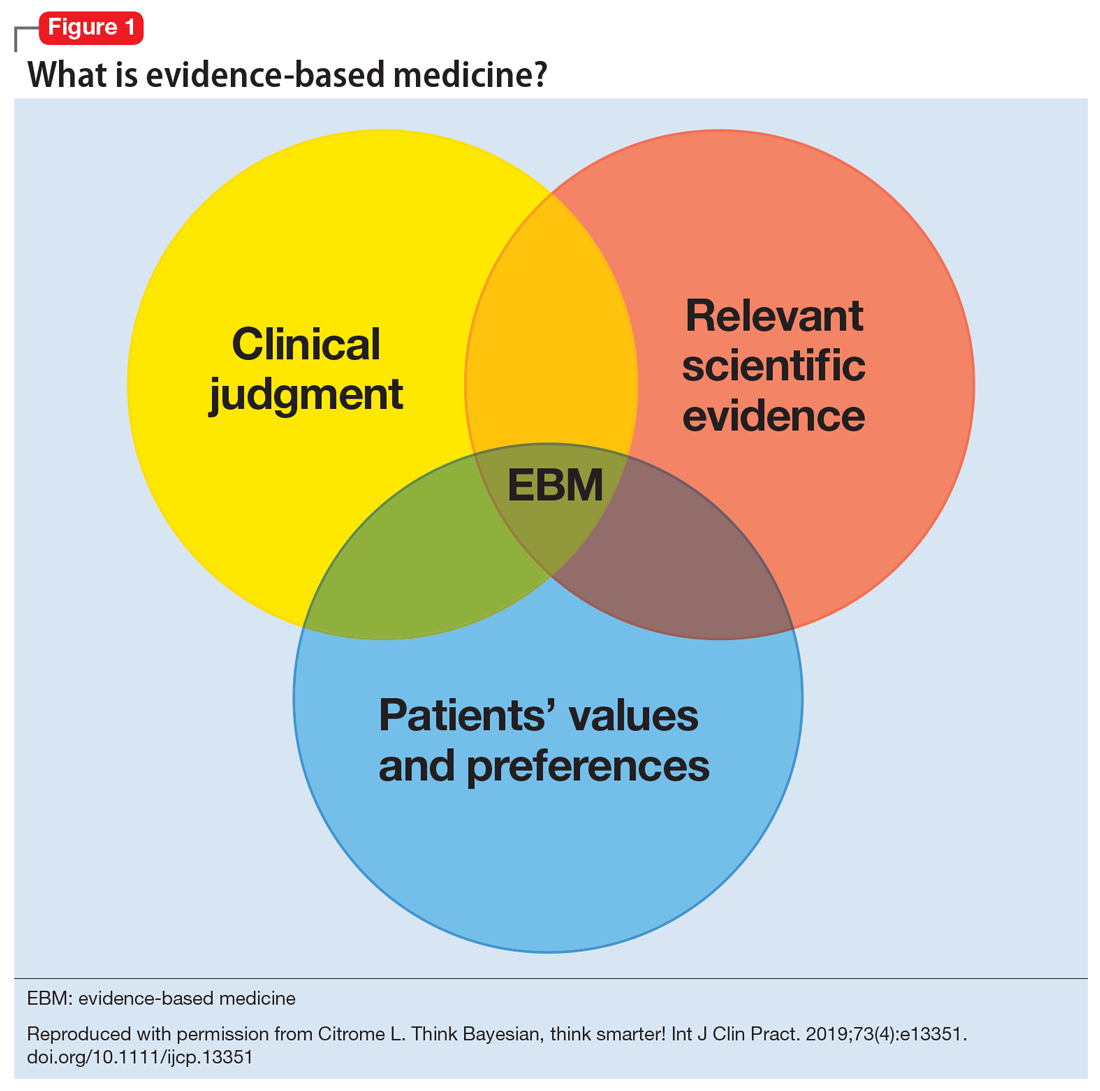

What is evidence-based medicine?

Sackett et al2 summed it best in an editorial published in the BMJ in 1996, where he emphasized decision-making in the care of individual patients. When making clinical decisions, using the best evidence available makes sense, but so does integrating individual clinical expertise and considering the individual patient’s preferences. Sackett et al2 warns about practice becoming tyrannized by evidence: “even excellent external evidence may be inapplicable to or inappropriate for an individual patient.” Clearly, EBM is not cookbook medicine.

Figure 13 illustrates EBM as the confluence of clinical judgment, relevant scientific evidence, and patients’ values and preferences. The results from a clinical trial are only one part of the equation. As practitioners, we have the advantage of detailed knowledge about the patient, and our decisions are not “one size fits all.” Prior information about the patient dictates how we apply the evidence that supports potential interventions.

The concept of EBM was born out of necessity to bring scientific principles into the heart of medicine. As outlined by Sackett,4 the practice of EBM is a process of lifelong, self-directed learning in which caring for our own patients creates the need for clinically important information about diagnosis, prognosis, therapy, and other clinical and health care issues. Through EBM, we:

- convert these information needs into answerable questions

- track down, with maximum efficiency, the best evidence with which to answer questions (whether from clinical examination, diagnostic laboratory results, research evidence, or other sources)

- critically appraise that evidence for its validity (closeness to the truth) and usefulness (clinical applicability)

- integrate this appraisal with our clinical expertise and apply it in practice

- evaluate our performance.

Over the years, the original aim of EBM as a self-directed method for clinicians to practice high-quality medicine was morphed by some into a tool of enforced standardization and a boilerplate approach to managing costs across systems of care. As a result, the term EBM has been criticized because of:

- its reliance on empiricism

- a narrow definition of evidence

- a lack of evidence of efficacy

- its limited usefulness for individual patients

- threats to the autonomy of the doctor-patient relationship.

These 5 categories are associated with severe drawbacks when used for individual patient care.5 In addition to problems with applying standardized population research to a specific patient with a specific set of symptoms, medications, genetic variations, and unique environment, it can take years for clinicians to change their practices to incorporate new information.6

Continue to: Evidence that is too narrow...