In 2021, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States.1 Suicide resulted in 49,000 US deaths during 2021; it was the second most common cause of death in individuals age 10 to 34, and the fifth leading cause among children.1,2 Women are 3 to 4 times more likely than men to attempt suicide, but men are 4 times more likely to die by suicide.2

The evaluation of patients with suicidal ideation who have not made an attempt generally involves assessing 4 factors: the specific plan, access to lethal means, any recent social stressors, and the presence of a psychiatric disorder.3 The clinician should also assess which potential deterrents, such as religious beliefs or dependent children, might be present.

Mental health clinicians are often called upon to evaluate a patient after a suicide attempt to assess intent for continued self-harm and to determine appropriate disposition. Such an evaluation must consider multiple factors, including the method used, premeditation, consequences of the attempt, the presence of severe depression and/or psychosis, and the role of substance use. Assessment after a suicide attempt differs from the examination of individuals who harbor suicidal thoughts but have not made an attempt; the latter group may be more likely to respond to interventions such as intensive outpatient care, mobilization of family support, and religious proscriptions against suicide. However, for patients who make an attempt to end their life, whatever potential safeguards or deterrents to suicide that were in place obviously did not prevent the self-harm act. The consequences of the attempt, such as disabling injuries or medical complications, and possible involuntary commitment, need to be considered. Assessment of the patient’s feelings about having survived the attempt is important because the psychological impact of the attempt on family members may serve to intensify the patient’s depression and make a subsequent attempt more likely.

Many individuals who think of suicide have communicated self-harm thoughts or intentions, but such comments are often minimized or ignored. There is a common but erroneous belief that if patients are encouraged to discuss thoughts of self-harm, they will be more likely to act upon them. Because the opposite is true,4 clinicians should ask vulnerable patients about suicidal ideation or intent. Importantly, noncompliance with life-saving medical care, risk-taking behaviors, and substance use may also signal a desire for self-harm. Passive thoughts of death, typified by comments such as “I don’t care whether I wake up or not,” should also be elicited. Many patients who think of suicide speak of being in a “bad place” where reason and logic give way to an intense desire to end their misery.

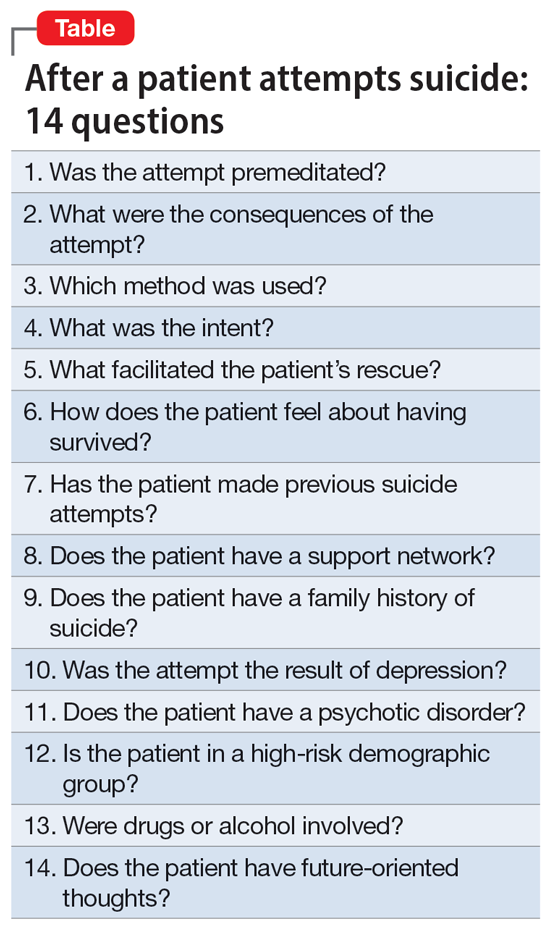

The evaluation of a patient who has attempted suicide is an important component of providing psychiatric care. This article reflects our 45 years of evaluating such patients. As such, it reflects our clinical experience and is not evidence-based. We offer a checklist of 14 questions that we have found helpful when determining if it would be best for a patient to receive inpatient psychiatric hospitalization or a discharge referral for outpatient care (Table). Questions 1 through 6 are specific for patients who have made a suicide attempt, while questions 7 through 14 are helpful for assessing global risk factors for suicide.

1. Was the attempt premeditated?

Determining premeditation vs impulsivity is an essential element of the assessment following a suicide attempt. Many such acts may occur without forethought in response to an unexpected stressor, such as an altercation between partners or family conflicts. Impulsive attempts can occur when an individual is involved in a distressing event and/or while intoxicated. Conversely, premeditation involves forethought and planning, which may increase the risk of suicide in the near future.

Examples of premeditated behavior include:

- Contemplating the attempt days or weeks beforehand

- Researching the effects of a medication or combination of medications in terms of potential lethality

- Engaging in behavior that would decrease the likelihood of their body being discovered after the attempt

- Obtaining weapons and/or stockpiling pills

- Canvassing potential sites such as bridges or tall buildings

- Engaging in a suicide attempt “practice run”

- Leaving a suicide note or message on social media

- Making funeral arrangements, such as choosing burial clothing

- Writing a will and arranging for the custody of dependent children

- Purchasing life insurance that does not deny payment of benefits in cases of death by suicide.

Continue to: Patients with a premeditated...